By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

The tattered banners of Hercules fluttered in the howling wind along the Frigidus River in western Italy, hard athwart the Adriatic Sea, on the afternoon of September 6, 394 ad. For two days, the Roman emperor Theodosius the Great had mercilessly hurled his Goth warriors against the soldiers of a rank usurper, Eugenius of Gaul, outside the village of Aquileia. The Goth captain Alaric, a favored protégé of the emperor, watched the dead pile higher and higher while ravens plucked the flesh and eyes from the bodies of friend and foe alike. The bloodbath ended with a great victory for Theodosius, but more than half his 20,000 Goth warriors lay dead on the riverbank. But the Goth sack of Rome would spell more bloodshed and disaster just 16 years later.

The men who fought for Rome that day on the banks of the Frigidus River bore little resemblance to the proud citizen legionaries of Julius Caesar’s days. Most Romans had come to despise military service, once an honored profession. Why risk your own life in a war when there were plenty of foreigners willing to fight and die for Rome instead? More and more barbarians from beyond the imperial borders were enrolled in the army, then were sent to protect the frontiers from the incursion of other barbarians much like themselves. Since the barbarians were from martial cultures, they did not mind fighting for the Romans. What they did mind was being sacrificed in battle while the Roman legions hung back. Nor did they care for the way the Romans looked down upon them as smelly, brutal, boorish savages. Still, the Goths respected a great soldier-emperor like Theodosius, who had always dealt with them firmly but fairly. When Theodosius died in 395 ad, the Empire was partitioned between his two sons, 18-year-old Arcadius, who ruled the east, and 11-year-old Honorius, who presided over the west.

The Rise of Alaric, the Goth

The Goths eyed the young emperors’ shifty court advisers with native suspicion. It seemed increasingly apparent that Theodosius’s promises and goodwill had died with him. There was even worrisome talk of the Goths’ yearly subsidies being reduced or abolished altogether. Once again, uncertainty lay in the Goths’ future. To face it head on, the chiefs elected 25-year-old Alaric, of the noble house of Balthi, to safeguard their interests. Born on an island at the mouth of the Danube, Alaric had hoped one day to command the legions of Rome himself. Along with other talented Goth youths, he had attended Theodosius’s state-sponsored School for Generals for five years. There veteran Roman soldiers gave him intensive training in the art of war, from weaponry and horseback riding to the study of tactics, diplomacy, and foreign languages—Greek, Roman, Aramaic, and German. The emperor himself sometimes conducted classes, as did his Master General, Flavius Stilicho. Favored cadets such as Alaric enjoyed the hospitality of the royal family, and the young Goth became friends with Theodosius’s sons, Arcadius and Honorius, and his youngest daughter, Galla Placidia. He would meet them all in less congenial circumstances in the years to come.

After Arcadius reduced the Goths’ stipend, angry calls for revenge went up among the barbarians. To reaffirm the Goths’ favored position within the Empire, Alaric felt the need to lead his people in a new war against the same legions they had fought alongside at Aquileia. Throughout their ceded homeland of Moesia, northwest of Constantinople, Goth warriors cast aside their plows and took up their spears once more.

From the trackless forests north of the Danube, the fierce, bearded barbarians heeded Alaric’s call, rolling their ponderous war wagons across the broad and icy Danube. The Goths swept unopposed through Macedonia and Thrace until they approached the outskirts of Constantinople. Teenaged Emperor Arcadius possessed neither the courage nor the troops to meet the Goths in open battle. Even so, Alaric soon realized that the city’s lofty walls were beyond his means to conquer. Instead, he turned west toward Thessaly, where Flavius Stilicho, now the supreme commander of the western Roman armies, waited to confront him. Alaric knew that Stilicho was not a man to be trifled with. The son of a Vandal cavalry officer and a Roman mother, Stilicho had worked his way up to become the most powerful man in the Empire. He had with him not only the crack troops of the West Roman army, but the Eastern Roman field army as well.

Behind a hastily built stockade at Thessalonika, Alaric awaited an assault by Stilicho’s numerically superior forces. The attack never came. Seeds of distrust had sprouted between the two Imperial courts. The self-serving court advisers who held Aracadius’s ear were worried that Stilicho, who already had complete control over Honorius, would extend his influence over the Eastern Empire as well. Arcadius ordered Stilicho to send the eastern army to Constantinople and return to Italy immediately. A baffled Alaric watched as Stilicho’s army suddenly broke camp and departed the field. The Goths marched unopposed down the historically fateful path to Thermopylae. Attica’s villages went up in flames, their men succumbing to Goth spears and their women becoming the conquerors’ spoils of war. Alaric spared Athens in return for most of its treasures. After a triumphant entrance, he relaxed with a warm bath and attended a banquet in his honor. From Attica, the Goths moved down the Peleponnese peninsula, where Corinth, Argos and Sparta yielded their treasures as well.

Stilicho Strikes Back

In the spring of 397 ad, the sails of a massive armada billowed above the azure waves of the Ionian Sea. Stilicho was returning with a powerful force to put an end to Alaric’s outrages. He drove the Goths up the arid slopes of Mount Pholoe, where the beleaguered barbarians hunkered down for a last stand, hunger gnawing at their ribs and thirst parching their throats. Defeat seemed inevitable. With victory all but won, Stilicho took time to enjoy the theaters and dancers of Greece. Unfortunately, so did many of his troops, who made themselves a nuisance in the countryside. Alaric saw his chance and broke through the depleted encirclement, transporting his troops, captives, and loot to the Epirus coast of northwestern Greece. The ease of Alaric’s escape stirred rumors that Stilicho had purposely let Alaric go so that he could later use him against the Eastern Empire. At the same time, the Eastern Empire was hoping to use Alaric against Stilicho. Having just wreaked havoc over much of the Eastern Empire’s domain, Alaric was awarded the post of Master of Soldiers and the Prefecture of Illyricum. The fox was now guarding the henhouse.

Illyricum was of no small importance to the Empire. The Prefecture covered all the Greek and Balkan provinces outside of Thrace. Both the eastern and western courts desired jurisdiction over Illyricum. Alaric had attained his original goals, and his people were pleased. In the time-honored custom of the barbarians, they lifted him high on a shield and rousingly proclaimed him their king. For the next four years there was peace in Illyricum, but Alaric’s Goths were not the only barbarians stirring up trouble within the Empire. An independent contingent of Goth mercenaries at Constantinople seized control of the city. They were quickly overthrown, and 7,000 of them were massacred inside the city. The resultant anti-German sentiment at Constantinople turned against Alaric and his Goths, who were stripped of their titles and lands.

It was time for the Goths to load up their wagons, mount their horses, and make the Empire take notice of them again. The west looked enticingly vulnerable at the moment. Vandals and Alans led by an eastern Goth warlord named Radagaisus, were advancing from Pannonia, and Stilicho was even now moving against them. With Stilicho squaring off against Radagaisus, Alaric’s Goths tramped into unprotected Italy in November 401 ad. The invasion sent shock waves of terror through the Roman Empire. Most of the towns of Venetia fell to Alaric while Honorius quivered in fear in Milan, the seat of emperors since the end of the 3rd century ad, praying for Stilicho’s imminent return. In the midst of winter, Stilicho smashed Radagaisus’s invasion. Radagaisus escaped, but otherwise the haul of captives was so great that the price of slaves plunged on the open market. Stilicho then led his battle-hardened veterans through the snow and ice of the Alps. With them marched 12,000 of the defeated Vandals and Alans, who had been drafted into the Roman army. Stilicho was taking no chances against Alaric. Far away, along the forts of the Rhine and the Caledonian border, his messengers raced to summon all available aid against the Goths.

By the time Stilicho returned in February 402, Alaric had pillaged northern Italy for three months. At the Imperial palace of Milan, the palace attendants cried that Alaric’s cavalry was already riding through the suburbs. Terrified, Honorius fled Milan. Nearly captured by the Goth horsemen, he found shelter in the walled Ligurian town of Asta on the River Tanarus. As the footfalls of Stilicho’s army drew near, Alaric conferred with his long-haired chieftains. He looked at faces scared from battle, at old warriors leaning on their spears. One of the eldest had given Alaric his first bow and quiver. The grizzled veteran advised Alaric to escape from the spreading Roman net while he still had time. Unabashed, Alaric retorted that “witless age” had deprived the old man of his senses. “This land shall be mine whether I hold it in fee as a conqueror or in death as conquered,” he declared. With those defiant words, he decided to pursue the emperor to Asta.

The Easter Surprise Attack

At Milan, the lookouts on the walls could not tell if the dust cloud raised by Stilicho’s approaching army heralded friend or foe. When Stilicho’s helmet, glittering like a star, was recognized, the population broke out in relieved jubilation. Stilicho did not tarry in the city for long before pressing on after Alaric. He found the Goths encamped near Pollentia, having put Asta under siege. The Romans enjoyed a 2-to-1 superiority over Alaric’s estimated 20,000 warriors. Despite such odds, however, Stilicho was too prudent to waste his men in an assault on the Goth wagon barricades. Instead, he enclosed the Goths within a line of fortifications and waited until April 6, Easter Sunday, when Alaric and his men, who were Christians of the Aryan faith, devoutly celebrated the festival. Riding along the ranks of his soldiers, Stilicho shouted: “Friends of Rome, the time has come for you to exact vengeance for outraged Italy! Protect Father Tiber with your shields!”

Saul, the pagan chief of the Alans, was called upon to lead the attack. His short but stout frame crisscrossed with battle scars, Saul looked to the flank of the barbarian legions. Alan horses nervously pawed the ground. Their bushy-haired riders swore oaths to the sacred sword of their steppe war god. Fierce nomads of Iranian origin, the Alans customarily draped their horses with the skins of their foes. At length the signal was given, trumpets blared, and the Alan cavalry dashed forward. The Goths did not expect an attack on such a holy day— surprise was total. The Alan riders jumped the barricades, stampeding through the confused Goths at the fringes of the camp. Stilicho would have clinched victory then and there had it not been for Alaric. The young Goth king instantly rallied his troops. Brawny Goth fists tightened their grip on their shields and spears as the Alan cavalry thundered closer. The Alan horses skidded to a halt, refusing to impale themselves upon the Goth spears. Blades flashed out of dust clouds. After Saul was struck down, his warriors broke in panic. Confident that on this day of all days God would be with them, the Goth cavalry galloped after the Alans with a roar.

Seeing his infantry about to be outflanked, Stilicho quickly flung a reserve legion into the battle. Buffered by the legion, the Alan horsemen turned on their pursuers. Alan and Goth cavalry sliced through each other’s ranks, their two-handed lances knocking riders from their steeds. Along the entire front, the Goth and Roman lines heaved back and forth. Spears stabbed through walls of shields, while yard-long “spatha” swords splintered shields and glanced off helmets. In the melee, the soldiers had to look at the designs and elaborate colors of their shields to tell friend from foe. The shields presented a dizzying array of colorful lines, rectangles, ovals, and animal motifs.

A short lull interrupted the battle. Soldiers, exhausted in their heavy iron chain mail, caught their breath before hurling themselves again into the bloody fray. By evening the maddening clamor of blaring horns, shouting men, neighing horses, and clashing arms finally quieted down. Only the pitiful groans of the wounded continued. Both sides had suffered horrendous casualties, and Alaric had no choice but to retreat or face complete destruction. The Goths abandoned both their loot and their women. Alaric had promised his wife jewels and Roman handmaidens—she got slavery instead. Violated and dragged into Roman servitude, the women clung to the hope that their husbands would soon come to free them. Meanwhile, the Italian and Greek women enslaved by the Goths were freed to return to their homes and families.

The Rise and Fall of Stilicho

Honorius, with Stilicho at his side, led his chariot in a triumphant procession through the streets of Rome. The celebrations were woefully premature. Alaric was not finished yet, although for a time he was forced to leave Italy. Angry and vengeful, the Goths prowled Italy’s northeastern borders. In 403, when the leaves had turned brown and yellow with the fall, Alaric assaulted Verona. Again Stilicho caught and defeated the Goths, and again he failed to finish them off. Alaric retreated into eastern Illyricum, an outlaw at large in the Empire. The setbacks caused a number of Goths, including Sarus, a hereditary enemy of Alaric’s house of Balthi, to defect to the Roman side.

Alaric and his Goths licked their wounds and waited for events to turn again in their favor. Fortunately for Alaric, Stilicho still hoped to use him to help wrest Illyricum from the Eastern Empire and add it to Honorius’s jurisdiction. Within a year, Stilicho somehow convinced Honorius to reappoint Alaric as Master of Soldiers at Illyricum. This was a complete slap in the face of the Eastern emperor, Arcadius, who was still the legal sovereign of Illyricum. Stilicho’s plans were interrupted in 405 ad when Radagaisus led a huge eastern Goth invasion from the Danube basin. Stilicho crushed it and executed Radagaisus. The next year, however, Vandals, Suebi, and Alans poured into Gaul, overwhelming the depleted frontier defenses. Despite the deteriorating situation, Stilicho remained fixated on Illyricum. He sent a message to Alaric: “Along with me make war on the Eastern Emperor, strip Illyricum from his realm and annex it to Honorius.” In 408, the barbarian leader marched into Noricum (southern Austria and Slovenia) and demanded 4,000 pounds of gold for his troubles—the yearly tribute due to him. The Roman Senate was horrified, protesting that “this is not a peace, it is a commitment to slavery.”

In exchange for his payment, Alaric was to move against Constantinus. It never happened. Alaric never got his gold, and a series of interrelated events collapsed the teetering Western Empire like stack of dominos. Arcadius suddenly died, leaving seven-year-old Theodosius II as his heir. Stilicho characteristically saw this as an opportune moment to press for Illyricum, but the recent setbacks had undermined Stilicho’s popularity with the Romans. Even the legions muttered in discontent. The Romans whispered that Stilicho had failed to rid the Empire of Alaric because Alaric was a German barbarian like himself. No one seemed to remember that Stilicho had a Roman mother, that he had grown up in Roman culture, and that he had saved Rome many times. The barbarians were to blame for all Rome’s ills—and Stilicho was a barbarian.

A palace official named Olympius spread the rumor that Stilicho was plotting the assassination of young Theodosius so that he could hand over the Empire to his own son. The allegations laid the groundwork for Olympius’s palace revolt. On August 13, 408 ad, Honorius summoned his legion commanders to his quarters. Not one of them stirred at his orders. Instead, they looked to Olympius, who gave them a nod. It was the signal to begin killing Olympius’s enemies, who were dragged screaming from the emperor’s feet into the street and cut down in cold blood. Worried about Honorius’s safety, Stilicho hastened to his side. Honorius, however, had already decided to save his own skin and side with the mutineers. Stilicho was bound in chains and thrown into the dungeons. Although he made some bad judgments, Stilicho had served the Empire loyally for 23 years. Despite his service, on August 22 Stilicho was led outside and beheaded. His remaining supporters were clubbed to death. All the now-vacant positions were given to Olympius’s friends.

The Roman hatred of Stilicho spilled over to the barbarian auxiliaries serving in the army. In one town after another, the legionaries massacred Alan, Vandal, and Goth families whose husbands and fathers had been enrolled by Stilicho. Some 30,000 barbarian soldiers and surviving women and children fled to Alaric. Only Sarus’s Goths and a number of Huns remained with the Romans. Olympius conferred with Honorius about what to do next. On the positive side, Stilicho’s death had restored relations between the eastern and western courts. This was of no help against Alaric, who demanded money and hostages in exchange for a promise to peacefully withdraw into Pannonia. Honorius refused. His offers spurned, Alaric crossed the Alps in the late summer of 409. His barbarian army quickly overran Aquileia, Concordia, Atltinum, and Cremona. Alaric bypassed Ravenna, the new seat of the Empire. Flanked by sea, rivers, and marshes, the fortress city was nearly as impregnable as Constantinople.

The Siege of Rome

Alaric moved on to seize Ariminum. He then turned to loot his way unopposed across the backbone of Italy, past villages nestled beneath limestone cliffs and through woods of oak and beech. The highlands gave way to brush and cultivated lands as his barbarian horde descended to the banks of the Tiber, to stand at last before the fabled walls of Rome. The city walls precluded a direct assault, prompting Alaric to blockade Rome’s 12 principal gates and stop provisions coming in from the Tiber River. Faced with incipient starvation, the Roman mobs seethed in anger at the barbarians, but were too cowardly to take up arms against them. Instead, they made Stilicho’s family their scapegoats. His son was murdered and his innocent widow, Serena, was strangled to death by order of the Senate.

Serena’s death did nothing to alleviate the people’s pangs of hunger. Daily rations dropped from three pounds of bread to one-third of a pound, then to nothing. Laeta, the wealthy, aged widow of the Emperor Gratian, did her best to aid the needy, but it was not enough to feed the insatiable hunger of Rome’s one million inhabitants. Emaciated corpses soon joined the refuse that polluted the city’s narrow, winding streets.

Men whispered darkly of cold-blooded murders in desolate alleys, of loathsome wretches whose hunger had driven them to feed on the dead. The stench of death hung over Rome, and the plague found a fertile breeding ground in the city. The Senate had no choice but to send envoys to parley for peace. When the envoys threatened Alaric with Rome’s armed populace, he laughed in their faces. “The thicker the hay, the easier it is mowed,” he joked. He would only break the blockade if all the gold, silver and other treasures of Rome were laid at his feet and the barbarian slaves were released from captivity. “What will be left to us?” exclaimed the envoys. “Your lives,” mocked Alaric.

The Senate was dumbfounded. There seemed no way out of their dire predicament. The pagans cried out for human sacrifices to the abandoned old gods, but such was the growing influence of the Christians in Rome that nobody was willing to carry out such sacrifices in public. All that was left was to beg Alaric for more reasonable terms. At last, in mid-December, he relented, demanding only 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silk tunics, 3,000 scarlet-dyed skins, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. As the royal treasury was empty, the citizens of Rome had to come up with the ransom themselves, but even this was not enough. Gold and silver statues had to be melted down and ornaments stripped from the graven images of the gods.

After receiving the treasures and hostages, Alaric kept his word and lifted the siege, but he did not leave Italy itself. Instead, he settled into Etruria for the rest of the winter. Alaric had done well—not only were the Goths sitting on a pile of booty, but their ranks were swelled with the newly freed barbarian slaves. More reinforcements were on the way as well. Athaulf, Alaric’s brother-in-law, led a body of Goths and Huns across the Danube and cut his way through leagues of Imperial territory. Near Pisae, however, 300 Huns in Honorius’s service sprang upon Athaulf’s columns. Firing from their swift ponies, the Huns’ compound bows took a deadly toll. Before Athaulf’s men could gather their numbers and drive off the raiders, 1,100 Goths had been killed or wounded.

Back in Italy, Alaric was ready to settle for being named Master of Soldiers of the impoverished frontier province of Noricum. This was a lesser rank than he had held in Illyricum, but Alaric desperately needed to provide food and shelter for the multitudes of Goths under his care. Meanwhile, Honorius faced another near-mutiny in Ravenna. Olympius, the newest scapegoat for the Empire’s woes, was dismissed and forced to flee Italy. The troops, however, did not quiet down until several other high-ranking commanders were exiled and subsequently killed by their guards. Honorius’s handling of the crisis must have raised his self-confidence—he refused Alaric’s latest demands. When it was suggested that Alaric might soften his already reasonable territorial demands if given Stilicho’s old title, Honorius scoffed that “such an honor should never be held by Alaric, or by any of his race.” To protect Rome from Alaric’s anticipated reprisal, Honorius released the flower of the legions from Ravenna. Some 6,000 Roman soldiers were heading toward Rome. Apparently, their commander, Valens, thought it was beneath his dignity to sneak around Alaric’s detachments. Alaric prepared an ambush and completely overwhelmed Valens’s puny army. Only a hundred legionaries ever reached Rome.

The Goth Sack of Rome: A Timeline of Events

At the end of 409, Alaric, now reinforced by Athaulf, marched on Rome with 40,000 Goth, Vandal, Alan, and Hun warriors. This time Alaric occupied the huge Port of Ostia, with its massive wave-breaking moles, deep, capacious basins, and numerous outbuildings. It was here that the great grain shipments from the Province of Africa were stored. Their food supply assured, the Goths welcomed the shelter from the violent rainstorms that marked the Italian winter. Proclaiming that his enemy was not Rome but Honorius, Alaric threatened to cut off Rome’s grain supplies unless the Senate elected a new emperor. Honorius having been of no help to them, the Senate obliged by placing the crown and purple on the city prefect, a Greek named Priscus Attalus. The fickle mob greeted the Senate’s choice with jubilation, not just in Rome but in Milan as well. Attalus boasted that he “would leave Honorius not even the name of Emperor nor yet a sound body, but would mutilate him and exile him to an island.” Confident of his new ally, Alaric marched immediately to besiege Ravenna.

With Attalus in Rome and Alaric’s army outside his gates, Honorius was deeply worried. He was about to flee to Constantinople when six legions, some 4,000 men, arrived from the eastern capital. With them manning the parapets and towers, Honorius felt confident enough to remain holed up in Ravenna. He had another ally as well. Count Heraclian of Africa closed his ports. No more ships laden with grain sailed into Ostia. Whatever grain was left in the magazines the Goths used for themselves. Famine again afflicted the Romans.

Alaric broke off his investment of Ravenna and reduced most of the cities of Aemilia, which had refused Attalus’s rule. In this he received no help from Attalus, who seemed capable only of conducting fruitless negotiations with Honorius and Heraclian. Alaric soon had enough and summoned Attalus to Ariminum to publicly strip him of the purple. He decided to have another try at negotiating with Honorius, whom he met in July 410, a few miles from Ravenna. Sarus, Alaric’s old enemy, was also in Ravenna. He did not wish to see peace between Alaric and the emperor. Yelling and waving their weapons, Sarus and his Goths tore through Alaric’s camp before hightailing it back to the safety of Ravenna’s bastions. Convinced that Honorius and Sarus were working together, Alaric angrily broke off talks and marched on Rome for the third time. This time he was in no mood for mercy.

Once more the barbarians were at the gates, blockading Rome and starving its hapless population. The Gothic slaves and servants asked themselves why they should suffer for their Roman masters, and at midnight on the night of August 24, 410 ad, a group of them stole to the Salarian Gate and opened it to their erstwhile kinsmen. The citizens of Rome awoke to the sound of the Goth trumpets—the enemy was inside the city. When the Goth sack of Rome was at its apex, the barbarians stormed through the streets, scourging the city for three nightmarish days. The palace of the historian Sallust was burned to the ground, and the aristocratic houses along the Aventine also went up in flames. The worst offenders were the Huns who served in Alaric’s army. Rich furniture was thrown out of windows, silk hangings were torn from the walls, jeweled flourishes were pried out of statues. Wealthy Romans were repeatedly pummeled and kicked until they revealed hidden treasures. At last the conquerors filed out of the wasted city, laden with booty and followed by throngs of captives. Among the latter was the stunningly beautiful sister of Honorius, Galla Placidia, who remained in comfortable captivity with her childhood friend Alaric.

The Legacy of Alaric

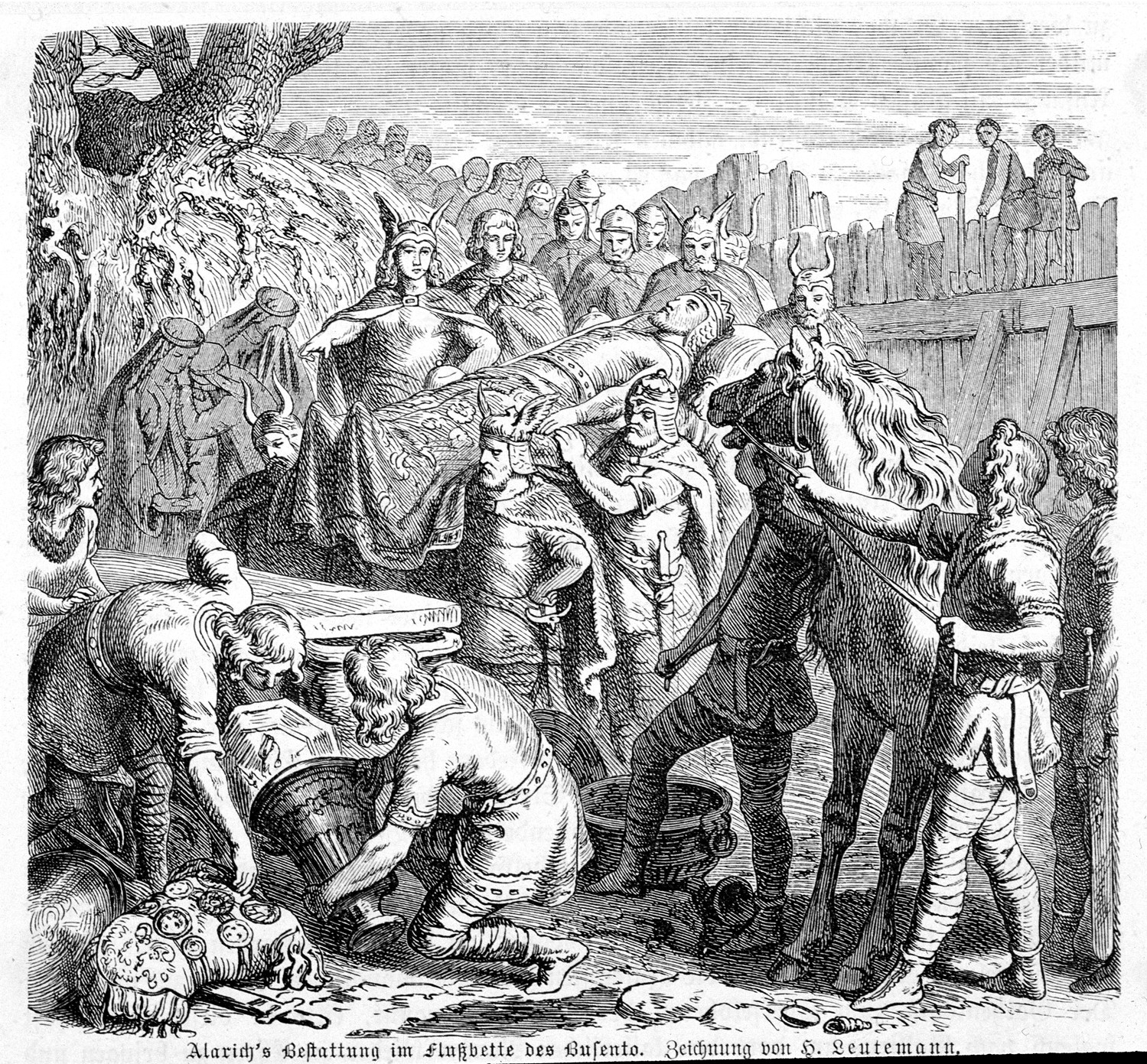

Alaric did not survive the Goth sack of Rome for long. He led his people south, planning to sail for Africa. At Cosenza, however, the Goth ruler was struck by a violent fever that killed him within a matter of days. Mourned by his people, Alaric was only 40 years old when he died. His bereaved followers dammed the Busento River, and slaves buried Alaric’s body alongside a trove of treasure in the dry streambed. To insure that no one knew the exact burial place, all the slaves were killed. The dam was then broken and the waters of the Busento washed over Alaric’s grave. Alaric died, but his people lived on. Athaulf married Galla Placidia and became the new king of the Goths. Under his leadership and those of succeeding kings, the Goths eventually settled in Spain, where they became known as the Visigoths, or “wise Goths.” Their rule lasted until the Islamic invasion of the early 8th century.

Honorius continued to preside over his fragmented Empire until his death in 423 ad. Although history has judged him a weak ruler, he managed to stay alive and remain in power in a political atmosphere that was more reminiscent of gang warfare than organized government. During his reign, however, Roman military losses were enormous. At least 50,000 soldiers of the field army, half its fighting strength, were killed. It was the beginning of many years of woe. In 455 ad, the Vandals laid waste to Rome again. Twenty-two years later, a barbarian king named Odoacer disposed of the last of the Roman emperors, Romulus Augustulus, bringing to an end over eight centuries of Roman domination of the western world.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments