By Michael E. Haskew

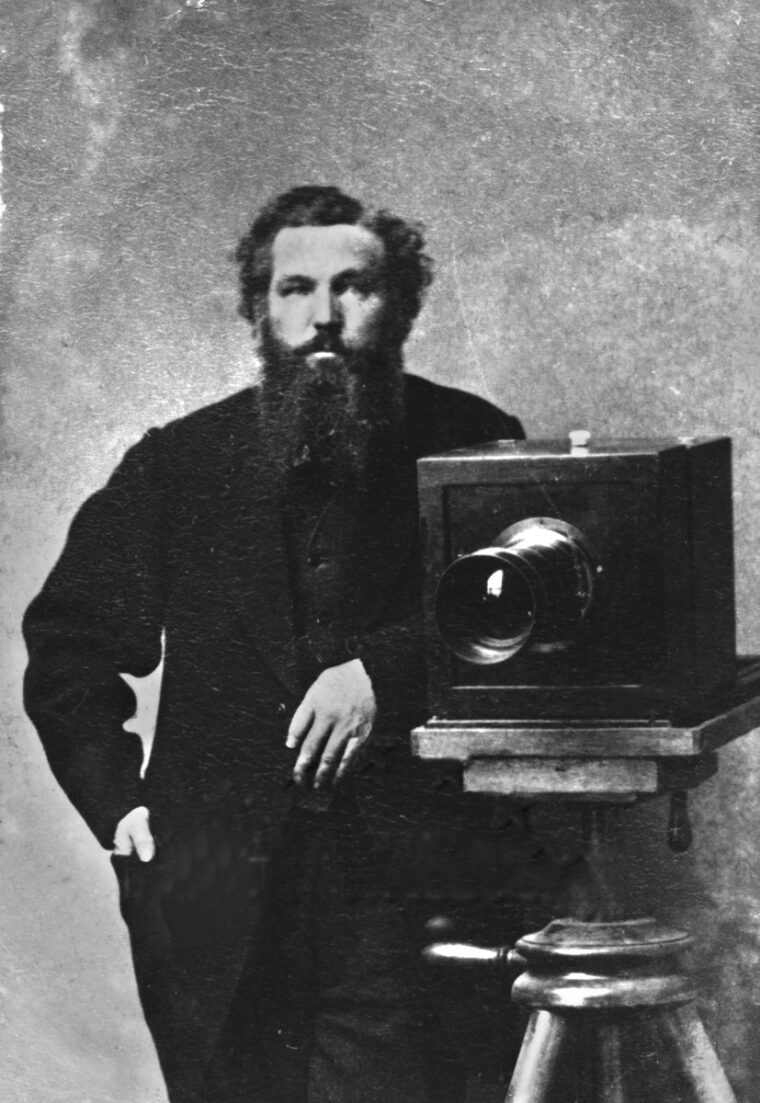

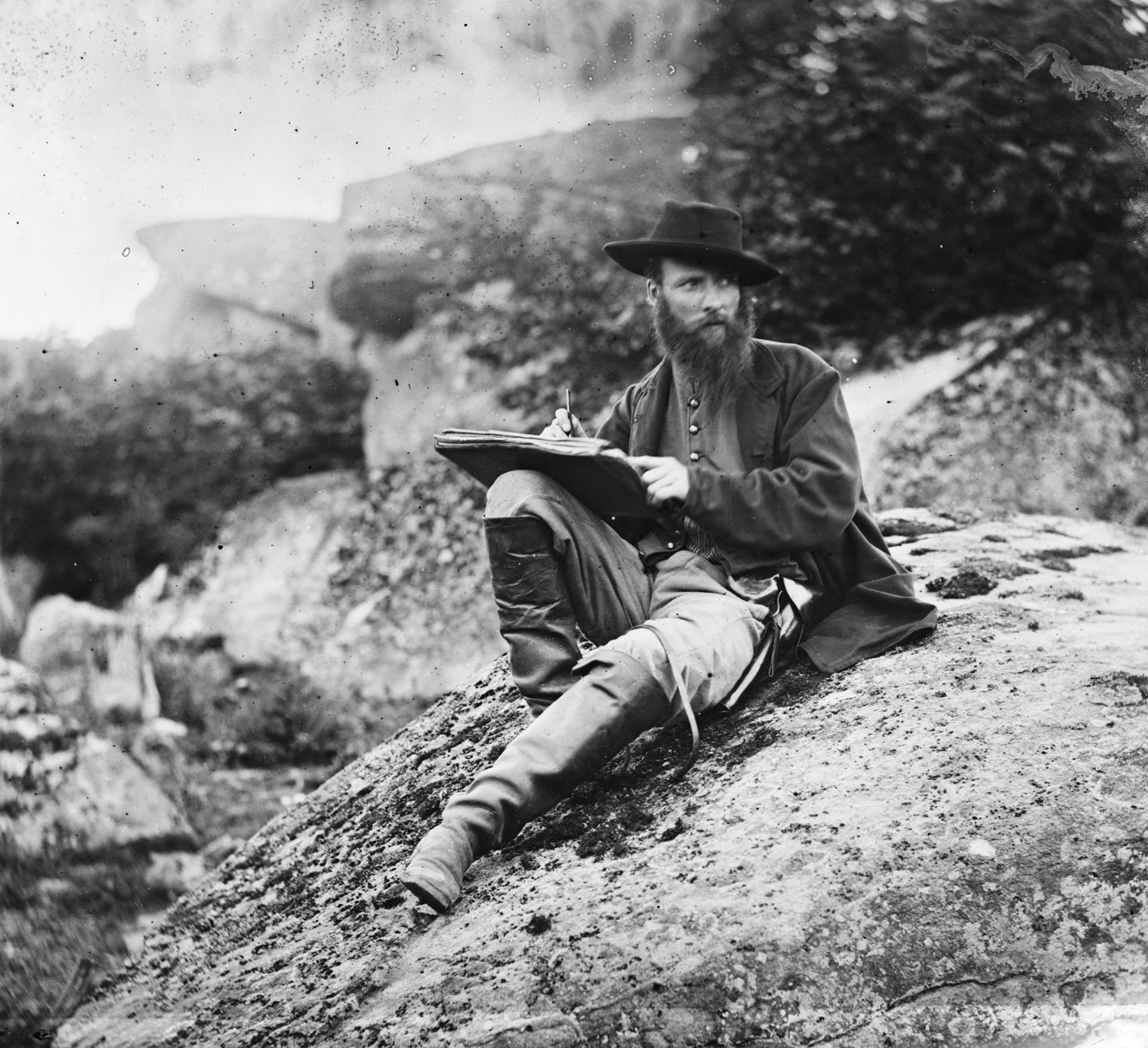

By the 1860s, photography itself was little more than 30 years old. Photographic techniques had progressed somewhat in three decades, but the process was still lengthy and the equipment was cumbersome. One of the most popular methods of outdoor photography, and the technique used by virtually all Civil War photographers, was known as the wet-plate process, which produced a plate-glass negative that could be printed on paper. First, a glass plate was coated with a flammable mixture called collodion, consisting of a number of chemicals, including pyroxylin, ether and alcohol, to sensitize the plate to light. Then the plate was coated with silver nitrate, placed in a container impervious to light, and fitted inside the camera. The photographer then removed the cap on the lens for a period of a few seconds to expose the plate to light.

The exposed plate remained in the container as the photographer carried it to his darkroom for development in a wash of pyrogallic acid before a solution of sodium thiosulfate fixed the image to guard against fading. The plate was then washed with water, dried and coated with varnish. Adequate light was critical to the wet-plate process, and the slightest movement blurred the image. Therefore, human subjects were required to remain completely still during exposure, even to the point of holding their breath. Outdoor photography was subject to sun, clouds and the rustle of wind through trees that created motion.

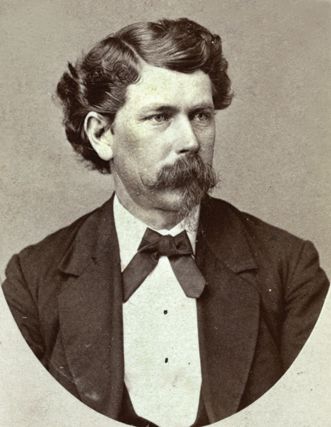

When General Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the North ended in disastrous defeat at Gettysburg, several photographers rushed to the scene. Three days of heavy fighting on July 1-3, 1863, left the small southern Pennsylvania town overwhelmed with the dead and wounded of both sides. Photographers Alexander Gardner, along with associates Timothy O’ Sullivan and James Gibson arrived with their horse-drawn traveling darkroom before many of the bodies were buried. Gardner and company produced 60 negatives during their Gettysburg venture, concluding their work by midday on July 7.

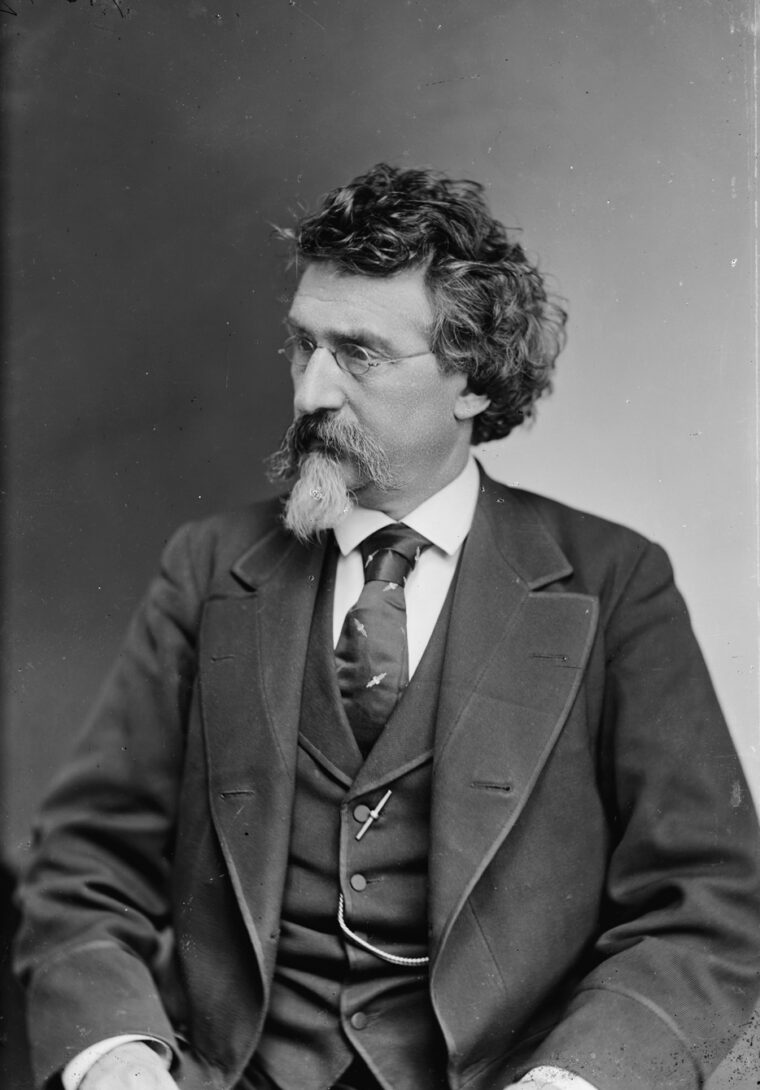

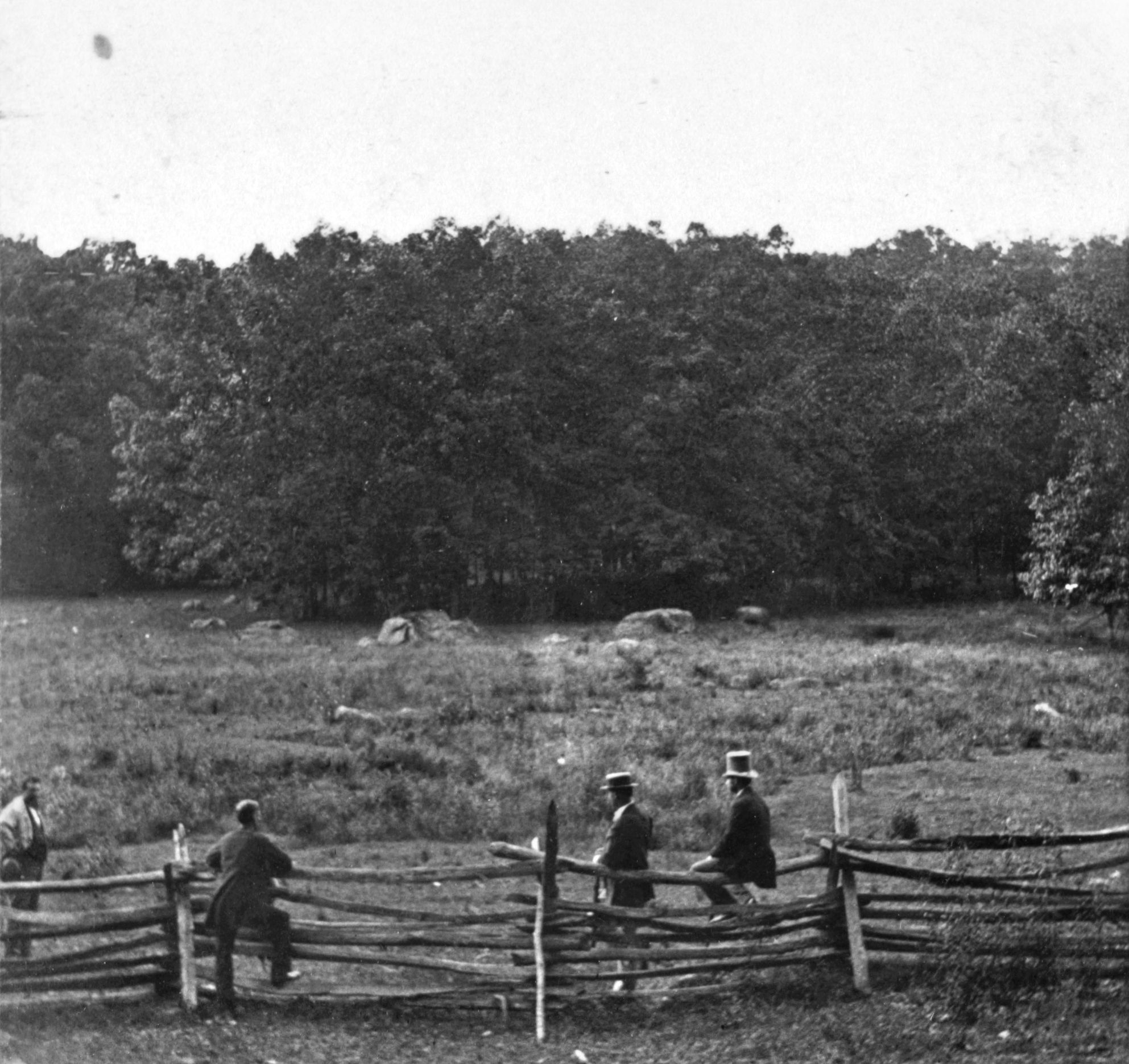

Matthew Brady led another team of photographers to the area about a week later and supervised their work, eschewing the camera himself due to his failing eyesight but actually appearing in some of the photographs wearing a long jacket and straw hat. Brothers Charles and Isaac Tyson, operators of a local portrait studio, fled the town during the battle and returned to photograph prominent locations later in the summer.

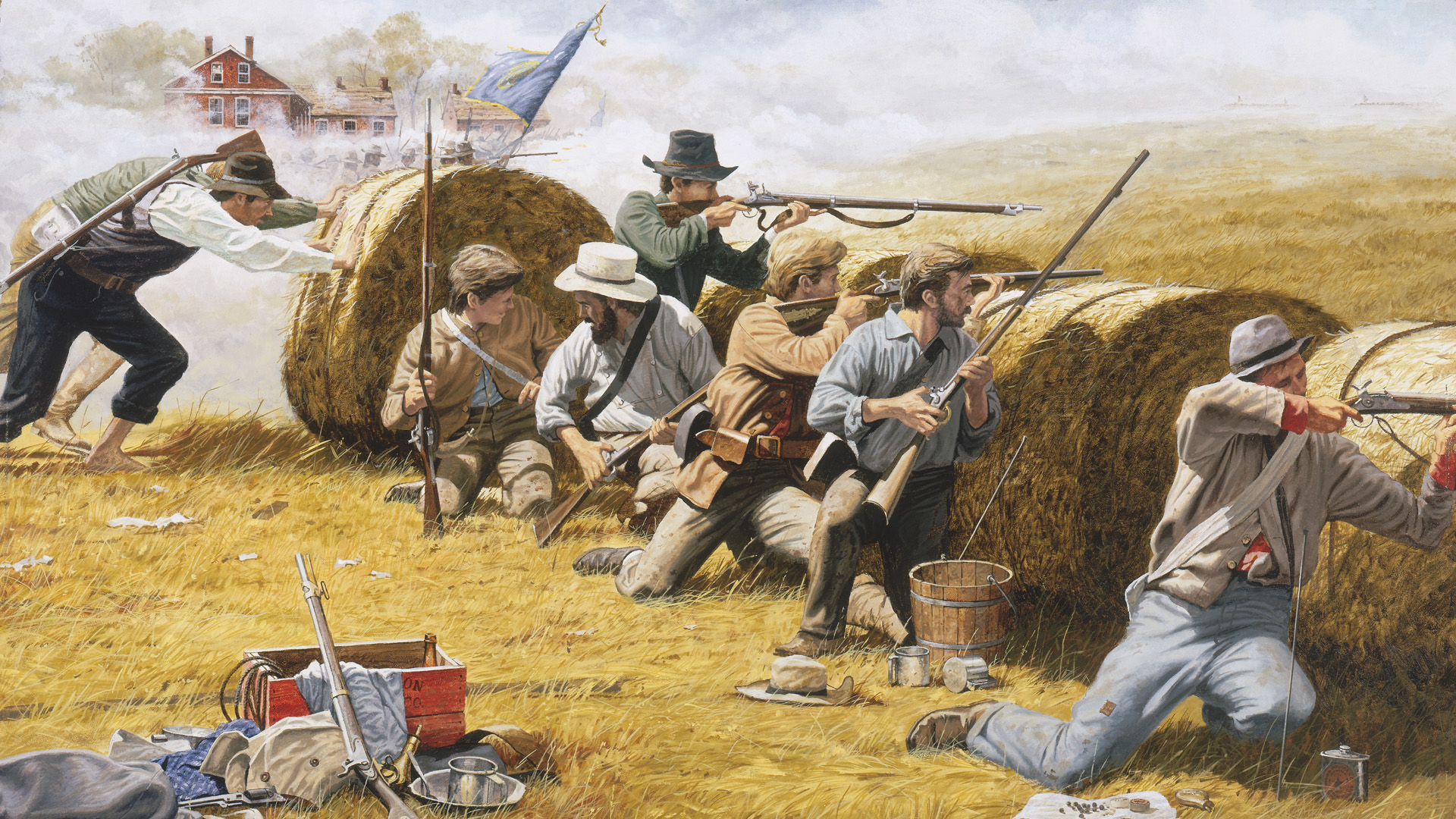

The photographic record of the Battle of Gettysburg brought lasting fame to such scenes of carnage as Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Little Round Top, Devil’s Den, the Slaughter Pen and the Rose Farm. Gardner, O’Sullivan and Gibson produced compelling death studies, and although the battlefield had been cleared of bodies by the time Brady arrived and the Tysons began their work, their frames are also historically significant for depicting the battlefield as it appeared in 1863.

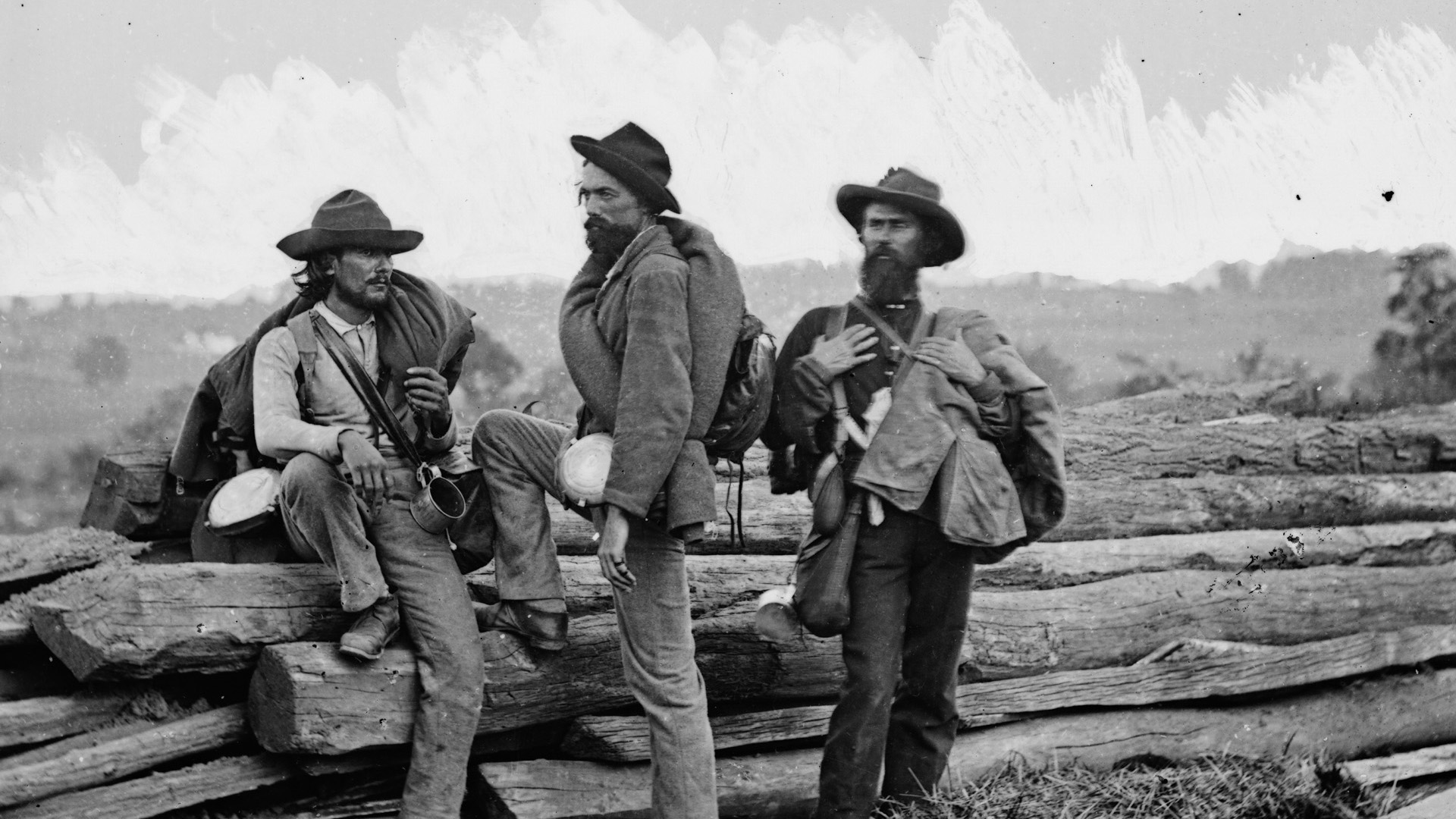

Among Brady’s best known images at Gettysburg were photos of a trio of Confederate prisoners posing along a rail fence on Seminary Ridge and a view of elderly Gettysburg civilian John Burns, who took up his musket and joined Union troops during the fighting. The Tyson works include the sprawling hospital at Camp Letterman, the field headquarters of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, and panoramic views of the town and its environs.

One of the most famous photographs of the Civil War, depicting a dead Confederate soldier lying next to a hastily stacked stone wall, was taken by O’Sullivan on July 6, and remains the topic of much theory and conjecture. Although some historians maintain that the photograph is authentic, photography expert William A. Frassanito asserts that the dead Confederate, labeled a “sharpshooter” by Gardner, had in fact appeared in previous photos and was moved approximately 40 yards to the final position. A rifle used as a prop in other photographs taken by the Gardner trio was placed against the stone wall to complete a touching tableau of glorious youth lost to the horrors of war.

In another O’Sullivan photograph, dead soldiers originally believed to be casualties of the Union 24th Michigan Infantry Regiment from the fabled Iron Brigade gathered for burial at McPherson’s Woods, were actually dead Confederates of either the 53rd Georgia or 15th South Carolina Regiment. Gardner grimly captioned the photograph “A Harvest of Death,” and apparently shared that caption with a second scene depicting Union soldiers killed defending the left of the Army of the Potomac at Devil’s Den, the Rose Farm or along the Emmitsburg Road.

When Philp & Solomons of Washington published the first edition of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War in 1865, Gardner supplied the accompanying text for the images. In the flowery prose of the day, he wrote: “Slowly, over the misty fields of Gettysburg—as all reluctant to expose their ghastly horrors to the light—came the sunless morn, after the retreat by Lee’s broken army. Through the shadowy vapors, it was, indeed, a ‘harvest of death’ that was presented; hundreds and thousands of torn Union and rebel soldiers—although many of the former were already interred—strewed the now quiet fighting ground, soaked by the rain, which for two days had drenched the country with its fitful showers.”

Gardner, O’Connor, and dozens of other photographers endeavored to document the Civil War. They left behind a legacy of photojournalism that has provided subsequent generations of Americans an unparalleled glimpse of life during the great conflict. Never before had warfare been so extensively documented.

Interesting that even in the technology’s infancy, photographers were already altering scenes to “improve” on reality.