By Mark S. Longo

Most Americans can recite the second line of the immortal “Marine Hymn” by memory, but few actually know what it means. In fact, the famous line, “To the shores of Tripoli,” refers to America’s limited engagement against the Barbary pirates at the dawn of the 19th century. It was our fledgling nation’s first attempt to exert its authority overseas. It was also America’s first conflict with an asymmetrical opponent in the Muslim world. This conflict, which came to be known as the Tripolitan War, eerily foreshadowed the modern war on terror. It also gave rise to one of the most interesting and bizarre characters in American military history “General” William Eaton.

Eaton was born in 1764 in rural Connecticut. He came from a farming family, but he had no interest in spending his life tilling the flinty New England earth. When war broke out between the American colonies and Great Britain, Eaton found a golden chance to escape. At the age of 15, he enlisted in the Continental Army. Unfortunately, the adventurous teen saw little action during his tour of duty. After three uneventful years spent mainly as a clerk, he left the service to pursue a higher education. Working his way through Dartmouth College, Eaton graduated in 1790, then took a job as a clerk in the Vermont House of Delegates.

Off to Battle the Indians

Eaton soon grew bored with politics and returned to the military as an infantry captain in 1792. He served his second tour under Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne, affectionately known as “Mad Anthony” by his subordinates. Wayne was a fighting man’s general, and he gave Eaton his first taste of combat during the Ohio Valley campaign. Eaton was assigned to the American Legion, a combined-arms unit consisting of infantry, artillery and light dragoons. In the course of the campaign, Eaton successfully infiltrated Miami Indian villages and even took command of a wilderness fort to repel a massive Indian counterattack. Under Wayne’s tutelage, he became adept at such time-tested Indian fighting techniques as camouflage and ambush. He would later put these skills to good use a long way from the rolling forests of the Ohio Valley.

When the Ohio Valley campaign ended in late 1794, Eaton was reassigned to Georgia where his main duty was to prevent attacks against the local settlers by Creek Indians. Eaton soon became familiar with the Creek language and customs, even briefly taking the daughter of a local chief as his bride. During his time in Georgia, there were no Creek uprisings or attacks on settlements. The State Assembly was so grateful that they offered Eaton a reward of $500, which he suavely declined, noting that the people of Georgia were poor and could put the money to better use improving their roads. In appreciation, the assemblymen made him an honorary citizen of Georgia and offered him his choice of land whenever he chose to settle down.

Along with keeping an eye on the Creek Indians, Eaton and his men were also responsible for guarding the Georgia border against the Spanish. At the time, Florida was a Spanish colony and there was a constant fear of incursion by Spanish troops. However, after the excitement of the Miami war, Eaton found duty as a border guard boring, and the boisterous young soldier didn’t take well to boredom. He began using his meager savings to invest in a number of speculative land deals in the West. These shady deals were surprisingly profitable and by October 1796 Eaton was a wealthy man, banking some $54,000 on his initial investment of $200.

Eaton’s newfound wealth attracted the attention of his commander, Colonel Henry Gaither. Gaither and Eaton had never gotten along, but their relationship worsened when the colonel lost his life savings speculating on another land deal. Eaton’s fiery temper only added to this volatile clash of personalities. The conflict ultimately came to a head that same autumn, and Gaither court-martialed Eaton for allegedly selling government supplies to the Creek Indians. Eaton was also accused of improperly using his time in the military to further his private land deals. He was convicted in absentia, but a review board soon overturned the conviction and chastised Gaither for bringing the charges. Nevertheless, the scandal tarnished Eaton’s reputation within the military. Realizing that his opportunities for promotion were limited and not wanting to remain under Gaither’s command, he resigned his commission in December 1796 and moved to Philadelphia. However, it would take six months for his resignation to take effect. In the meantime, he was still officially in the Army, although without specific duties.

Eaton’s Spying Career Begins

Secretary of State William Pickering came to the young officer’s aid. Eaton had ingratiated himself with the secretary when he shamelessly named a small mud fort in a Georgia swamp after him. As it turned out, Pickering had a use for a disgraced military officer such as Eaton, and he was recruited into a small counter espionage unit that was tasked with surveilling British and French spies inside the United States. The surveillance required a subtle touch, since America had shaky diplomatic relations with both nations. The upstart country had been free of British rule for less than a quarter-century, and it had only recently emerged from the Quasi-War with its former ally France. A major diplomatic embarrassment of either nation could lead to a resumption of hostilities, something the young country might not survive.

Given Eaton’s reputation as a firebrand, he seemed an odd choice for such delicate work. However, his court-martial and abrupt departure from the Army gave him the perfect cover to infiltrate the spy ring.

Eaton traveled to New York to find the ring’s suspected contact, Dr. Nicholas Romayne. Romayne was believed to be the intermediary used by British spies to deliver their reports, although nothing definitive could be proven. It was Eaton’s job to obtain that proof. In his signature direct style, Eaton walked into Romayne’s office and related the sad story of his court-martial and supposed departure from the Army. Romayne seemed particularly interested in his service along the Georgia border. He offered to pay Eaton to detail the American defenses along the border. Eaton immediately arrested the doctor and personally escorted him back to Philadelphia.

Eaton’s success as a counterespionage agent soon brought him to the attention of the White House. Newly elected President John Adams was worried about rumors of a planned Spanish invasion of Georgia. He needed someone to infiltrate a Spanish spy ring and determine if the rumors were true. Eaton’s military background and knowledge of the Georgia border made him the ideal man for the job. Eaton targeted a deputy Spanish ambassador named Don Diego de Rivera-Sanchez. Over a number of months, Eaton and Rivera-Sanchez became friends. The wily Eaton used the same ruse on Rivera-Sanchez that he had used on Romayne—he offered to sell his knowledge of American defenses along the Georgia border. However, this time he deliberately fed Rivera-Sanchez false information, claiming the border was well defended by an elaborate network of forts and soldiers. His ruse was successful. When the Spanish government heard of the bogus American defenses, they abandoned their invasion plans and agreed to negotiate a new treaty.

A Strange Assignmnet to Request: Tunis

Eaton’s second successful assignment earned him the gratitude of the president of the United States. Offered his choice of diplomatic postings, Eaton asked to become the American consul to Tunis.

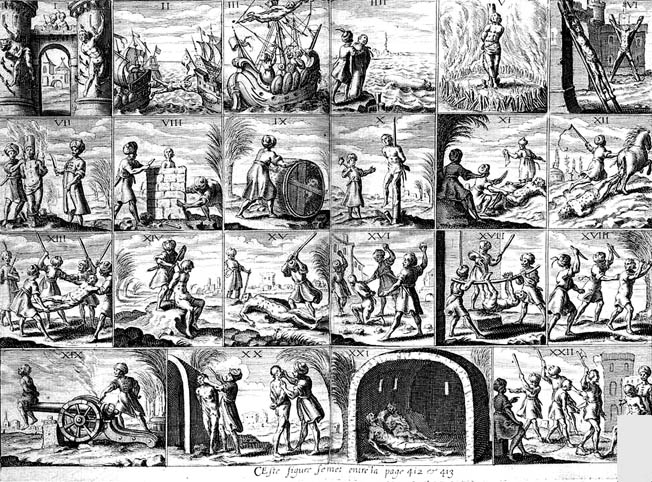

At the time, Tunis was a small backwater country on the northern coast of Africa—definitely not the first choice of someone looking to build a career in the Foreign Service. Tunis was one of the four Barbary states, along with Tripoli, Morocco, and Algiers. These outlaw Muslim nations had been preying on Christian shipping in the Mediterranean since the 8th century. Their location along the major trade routes was ideal for piracy, and they routinely attacked European and American merchant vessels. The Barbary pirates’ favorite tactic was to seize a merchant vessel, steal its cargo, and then ransom the ship and crew for a tidy profit. They also used the threat of future piracy to extort protection money, ships, and trade goods from America and Europe.

The pirates were so successful that by the end of the 18th century they had effectively closed the Mediterranean to American shipping.

However, Eaton was not discouraged by the Tunisians’ reputation for piracy. Ever since he was a young boy, he had been fascinated with Muslim history and Arab culture, routinely poring over the Koran and even learning to speak a few words of Arabic. When his chance came to visit the Muslim world, even if it was an outlaw state ruled by thugs, he leaped at the opportunity. Arriving for duty as the newly appointed American consul to Tunis in February 1799, one of Eaton’s first official acts was to revise the treaty of peace and friendship that America had signed with Tunis in 1797. This treaty included a number of disturbing provisions. Some were silly, such as the provision stating that America must give the Tunisian bey (king) a barrel of gunpowder every time his cannon fired a salute to an American vessel. Others were oppressive, such as a brutal 10 percent tax on all goods that passed through Tunis, even if they weren’t unloaded at the port. However, the most troubling provision effectively gave Tunisian pirates permission to commandeer American ships at any time, making trade between the two nations virtually impossible.

The fact that America had been forced to sign such an unfavorable treaty was a glaring admission of its weakness on the high seas. The American navy consisted of only a handful of ships, and while it had acquitted itself admirably during the brief Quasi-War with France, it could do little to stop pirates and privateers from preying on American merchant vessels in international waters. The sight of his country bowing to threats from the insolent Barbary pirates infuriated Eaton, and he was determined to put a stop to it.

Eaton and Famin Face Off

The terms of the existing treaty had been negotiated by Joel Barlow, the former American consul to Algiers. Barlow had been advised in the negotiations by a French expatriate named Joseph Etienne Famin, one of the legion of stateless rogues who gravitated toward the pirate nations of the Barbary Coast.

Famin and Eaton took an instant dislike to each other. Eaton blamed the Frenchman for negotiating the unfavorable treaty, while Famin saw Eaton as a threat to his lucrative position in Tunis. In addition to working as an advisor to the American government, Famin also made a tidy profit by selling “rights of passage” to American ships. These “rights” were promises to help bypass the steep Tunisian taxes on trade goods, although in actual practice they were worthless.

Eaton dismissed the Frenchman from American service soon after he arrived, but Famin would not go away so easily. He continued to advise Tunisian Bey Ahmed Pasha on how to milk more money from the Americans. He also did everything he could to thwart Eaton’s efforts to renegotiate the treaty.

Eaton’s legendary temper finally boiled over when he learned of Famin’s attempt to charge an American captain $1,000 to bypass Tunisian customs. Eaton confronted the Frenchman and, after a heated exchange, flogged him with a bullwhip until Famin collapsed.

Once again, Eaton’s impulsive temperament had gotten the better of him. The stakes this time were much higher than a simple court-martial. His outburst had not only jeopardized his position as an American consul, but it had also put his life in danger. Famin enjoyed the protection of the bey, and Eaton now faced expulsion, imprisonment, or even death at the hands of the irate Ahmed Pasha. The American remained unbowed. When the bey finally summoned him and asked why he had assaulted Famin, Eaton responded, “I’d have disciplined him in the same way in the Kingdom of Heaven. And if he so much as speaks to an American again, I’ll give him another whipping.”

His bravado and knowledge of Muslim theology impressed Pasha, who brushed off Famin’s complaints and sent him away unsatisfied. Eaton used his newfound friendship with Pasha to renegotiate the treaty of friendship and remove the unfavorable provisions. On April 10, 1800, Eaton wrote a celebratory letter to the other consuls, proclaiming grandly that “there is now no danger to be apprehended for American vessels visiting this coast. Perfect health prevails here.”

Eaton’s apparent success in Tunis increased his standing with President Adams and won him a congressional commendation. Unfortunately, his success was soon upstaged by an embarrassingly public American humiliation in Algiers.

America Humiliated in Algiers

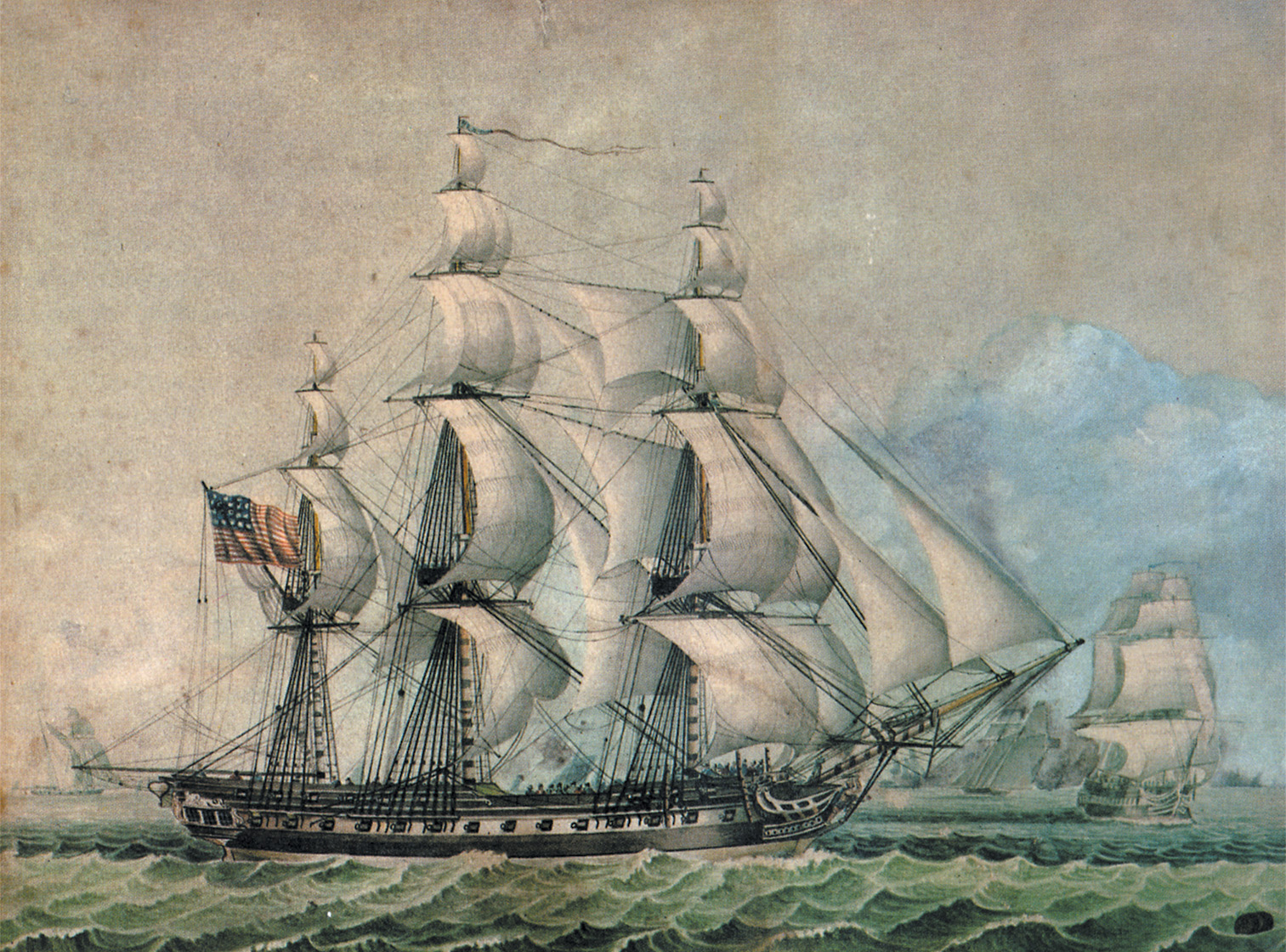

In September 1800, the frigate George Washington arrived in port to deliver America’s annual tribute to the Algerian bey, but the bey had more pressing matters on his mind than American extortion payments. He had recently offended the Ottoman Empire by signing a peace treaty with France. In order to avoid Ottoman retribution, he decided to send a shipment of gold, animals, and slaves to placate the Ottoman sultan. However, the voyage to Constantinople was long, and the bey didn’t want to send any of his own ships on the dangerous journey. The arrival of the George Washington solved all of his problems. He pointed his shore batteries at the vessel and threatened it with destruction unless the captain agreed to carry his tribute for him. The ship’s captain, William Bainbridge, had no choice but to comply. He loaded the tribute, raised the Algerian flag, and set off for Constantinople.

The American government was outraged when it learned that one of its own naval vessels had been commandeered and forced to sail under a foreign flag. Calls for war echoed across the country. It was during this tense time that James Cathcart, the American consul to Tripoli, requested Eaton’s help in negotiations with the Tripolitan bey. Eaton agreed and departed for Tripoli in December. It was a decision that would change his life and alter the political map of the region forever.

Tripoli was a backward country, even by the standards of the other Barbary states. It had been the scene of a series of bloody coups, revolts, and assassinations over the years. The latest coup occurred in 1795 when the three sons of Bey Ali struggled for power. Yusef, the youngest son, eventually succeeded in assassinating his oldest brother and driving his second brother, Hamet, into exile. With his position secure, Bey Yusef increased Tripolitan attacks on American shipping and demanded ever-larger tribute payments from the American government. When Eaton arrived in Tripoli in January 1801, the situation between the two countries had deteriorated and war was looming on the horizon. Eaton immediately arranged a meeting with Yusef, but the bey took advantage of the occasion to make more threats of imminent hostilities. Eaton later recorded vividly his impressions of Yusef at that first meeting:

“He was a large, vulgar beast, with filthy fingernails and a robe so spotted with spilt food and coffee that it was difficult to distinguish the orginal color of the garment…. [H]e rarely bathed, if ever, and the stench of his body, which mingled with the powerful scent he used to disguise the odors, made me want to retch…. He was an evil man, but evil in a petty, mean way. There was no grandeur in his bearing, his manner or his speech. There are tyrants who clothe themselves with regality, but Yusef Karamanli was not of their number. In Philadelphia he would have been a worker at the docks unable to find employment; in New York, he would have been a cutpurse hanged at the gallows; but such are the ways of Barbary that in Tripoli he was the master of the world.”

Eaton and Cathcart saw the war clouds gathering and wrote to Washington requesting troops and warships. The outrage over the George Washington incident was still fresh, and the public’s anger was compounded by Tripoli’s continued seizure of American ships. However, Bey Yusef decided not to wait for the American government to act. On May 14, his men entered the U.S. consulate in Tripoli and chopped down the American flag. The small Barbary nation had officially declared war on the United States.

Jefferson Sends a Squadron to Tripoli

With the public in an uproar, the incoming administration of Thomas Jefferson had little choice but to act. On May 15, barely two months into his presidency, Jefferson authorized America’s first attempt to show its strength overseas. He made this decision without knowledge of Tripoli’s declaration of war and without consulting Congress. It was ironic that Jefferson, an ardent proponent of the Constitution, would provide the precedent for all later presidents to engage in military action without congressional approval.

A squadron consisting of three frigates and one sloop finally departed for the Barbary coast on June 2, 1801. The four vessels weren’t the largest or most powerful warships afloat, but they boasted many cutting-edge designs. They were faster and more heavily armed than European frigates of the day. While they were no match for large ships-of-the-line, they could hold their own against the ragged fleets of the Barbary corsairs. Along with sailors, each American ship carried a complement of marines. The Marine Corps at that time was a new venture for the American military, having been created only three years earlier. The expedition against the Barbary pirates would be the Corps’ first trial by combat.

Although Eaton and the other consuls had requested an army to quell Yusef’s hostilities, the Marines were not intended as an invasion force. Instead, their purpose was to assist the squadron during naval combat. When battle commenced, the marines would be stationed on platforms in the rigging to snipe at enemy officers. They would also be used for hand-to-hand combat when repelling boarders or boarding enemy vessels. They could also be used for limited raids on the mainland, although the squadron’s small complement of 120 marines would not be effective in prolonged engagements against the bey’s forces.

A Missed Opportunity?

The full squadron arrived at the neutral harbor of Gibraltar on July 2. By a stroke of luck, they encountered Yusef’s head admiral aboard the Tripolitan flagship Meshouda. The admiral, Murad Reis, was another colorful example of the stateless brigands who prowled the Barbary coast. Born Peter Lisle in Scotland, he was wanted for crimes in numerous European countries. He eventually fled to North Africa and took up with the Tripolitan corsairs. Over time, he worked his way through the ranks and became the commander of the Tripolitan fleet, converting to Islam and changing his name to Murad Reis in honor of a legendary Muslim admiral. This strange character would be the first real test of America’s ability to exert its power in the Mediterranean.

The squadron didn’t learn of Tripoli’s declaration of war until they arrived in Gibraltar. Under the law of the sea, they could not attack the Meshouda in a neutral harbor, so the American frigate Philadelphia stayed behind to keep an eye on Reis while the rest of the squadron continued into the Mediterranean. Eaton was upset when he learned that the American ships had not attacked Meshouda. The capture of Reis and Meshouda, he wrote, “would be an event so fatal to the Bashaw of Tripoli that it would at once put an end to the war.”

The confrontation that Eaton sought never developed. Reis and his crew slipped off Meshouda under cover of darkness and, after a long land and sea journey, made their way back to Tripoli.

While Philadelphia remained behind at Gibraltar, the other two frigates, President and Enterprise, blockaded the harbor at Tripoli. Wth only two ships, it was mostly a symbolic gesture. The only real action of the campaign came when Enterprise left the harbor to resupply in August. Along the way, she came across the corsair vessel Tripoli. The ensuing battle was the first real contest between an American naval vessel and a Barbary pirate ship. Enterprise’s superior firepower won the day despite the pirates’ numerous attempts to trick them with false surrenders. Tripoli was captured, stripped of her weapons and cargo, and sent back to Bey Yusef in disgrace. Her unfortunate captain, Mahomet Rous, paid dearly for his defeat. The furious bey had Rous paraded through the streets of Tripoli sitting backward on a jackass with sheep entrails draped around his neck, then capped the humiliation with 500 lashes to his feet.

Jefferson used the incident as a rallying cry in his first speech to Congress, noting proudly:

“One of the Tripolitan cruisers having fallen in with, and engaged the small schooner Enterprise … was captured, after a heavy slaughter of her men, without the loss of a single one on our part. The bravery exhibited by our citizens on that element, will, I trust, be a testimony to the world that it is not the want of that virtue which makes us seek their peace, but a conscientious desire to direct the energies of our nation to the multiplication of the human race, and not to its destruction.”

Jefferson Bolsters the Mediterranean Force

Although Enterprise’s victory was a propaganda coup for the administration, the campaign as a whole was a dismal failure. Yusef continued to show his disdain for American naval power by attacking U.S. merchantmen at will. Eaton, having returned to Tunis during the campaign, was frustrated by the timidity of the American gesture and called for a firmer response. That response came in April 1802 when Jefferson dispatched a new squadron of warships that included the now-famous Enterprise. The six ships of the squadron joined with two others from the previous squadron to make a grand total of eight American warships in the Mediterranean. It was an impressive force for the young nation, and Eaton hoped it would finally strike a fatal blow against the upstart bey. Unfortunately, the commander of the squadron had other plans.

Commodore Richard Valentine Morris was a strange choice as commander of the American squadron. He had brought his wife along for the voyage and, instead of attacking Tripolitan cruisers, the two whiled away their time at various balls and diplomatic affairs. Morris made only a half-hearted attempt to blockade the harbor, and the bey’s corsairs were still able to carry out their raids on American shipping. Morris’s seeming reluctance to engage the enemy enraged Eaton. “Who but an American would ever propose to himself to bring a wife to war against the ferocious savages of Barbary?” he wrote to a colleague.

Eaton Rebuilds Through Unofficial Channels

Eaton did not sit idly by while waiting for the American squadron to end the conflict. Instead, he struck up a friendship with Hamet Karamanli, the deposed brother of Yusef, who had been wandering in exile throughout the Mediterranean. Eaton saw in Hamet a chance to depose Yusef and install a bey who would be far friendlier to American interests. Unfortunately, the grand scheme required the funds and backing of the American government and Eaton possessed neither. He had proposed his plan to the Jefferson administration earlier that year, but it received little interest.

That didn’t stop Eaton. If he couldn’t achieve his goals through official channels, then he would go around them. With his few remaining funds, Eaton purchased a small merchant vessel, Gloria, then proceeded to sell goods at ports throughout the Mediterranean. Using his consular position to arrange for his ship to sail under the protection of the American Navy, Eaton was able to charge exorbitant prices for his goods. His shady trade practices allowed Eaton to rebuild his squandered fortune and provide Hamet with a lifestyle befitting his exalted position. Eaton even used Gloria to evacuate Hamet from Tunis when he learned that Yusef had sent soldiers to kill his brother.

The budding friendship between Hamet and Eaton would provide the launching point for the grandest adventure of Eaton’s life.

It was none too soon. Eaton’s erratic career as a diplomat ended in March 1803 when Commodore Morris paid a visit to Tunis at Eaton’s request to negotiate the status of a Tunisian merchant vessel that had been seized by American ships. When the negotiations ended, Ahmed Pasha’s men forcibly prevented Morris and his entourage from leaving. As it turned out, Eaton’s shipping business had taken a turn for the worse, and he had borrowed a sizable sum from the bey to keep it afloat. Ahmed Pasha told Morris that he was his prisoner until Eaton’s debt was repaid. Morris was understandably outraged and vented his anger on the wayward consul. The two men eventually managed to repay the debt, largely with government funds delivered from the American squadron, but the incident deepened the rift between the two men. Morris was left with the lingering suspicion that Eaton had lured the squadron to Tunis merely to pay off his debts. If so, it didn’t work. Once the problem was resolved, Eaton was unceremoniously thrown out of Tunis by the bey, who had tired of his violent outbursts and erratic behavior.

Eaton returned to Washington to report on the sad state of affairs in the Mediterranean. He made an impassioned plea to Jefferson to remove Morris, who had followed his humiliation in Tunis by skirmishing fruitlessly with pirates at Tripoli and botching the first amphibious landing by American forces on foreign soil. Jefferson, however, was preoccupied with negotiations for the Louisiana Purchase and had little interest in the seemingly failed effort against the Barbary pirates. It wasn’t until May that Eaton’s advice was finally taken into consideration. Two more frigates, the powerful Philadelphia and Constitution, were dispatched to join the squadron, and the luckless Morris was recalled to Washington, court-martialed, and dismissed from the Navy for “his inactive and dilatory conduct of the squadron under his command.”

The Capture of the Philadelphia

The ensuing fate of the frigate Philadelphia would become the inadvertent catalyst that set Eaton’s grand plan into motion. While chasing a Tripolitan corsair on Halloween morning, 1803, the frigate ran aground on a reef near the entrance to Tripoli harbor. The helpless ship was quickly set upon by Tripolitan gunboats and forced to surrender. Some 307 crew members, including Captain William Bainbridge, were taken prisoner. When news reached Washington, it sparked a wave of outrage in Congress and throughout the country. Raiding American shipping was one thing, but holding the crew of a naval vessel hostage was beyond the pale. Bey Yusef compounded the insult by leaving Philadelphia afloat in the harbor as a symbol of his power. When high seas floated the vessel off the reef a few days later, Yusef’s navy had a ready-made 44-gun frigate as a gift. It was a flagrant affront to all American vessels in the region, and the commander of the American squadron, Commodore Edward Prebel, decided to strike back. Prebel’s retaliation would become one of the most memorable acts in American naval history.

On the night of February 16, 1804, the frigate Intrepid slipped silently into Tripoli harbor. Hidden in her hold was a boarding party of 70 commandos led by Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr. When Intrepid closed with her sister ship, the commandos burst out of the hold and engaged in a running swordfight with the Tripolitans. After a brief but bloody struggle, they secured the Philadelphia and prepared to destroy her. However, the sound of the battle had alerted the Tripolitan shore batteries of the American presence. Under a hail of cannon fire, the commandos set fire to the ship and escaped back to their own vessel. Living up to her name, Intrepid then slipped into the night past the burning wreckage of her erstwhile mate.

Decatur’s feat was widely hailed in America and throughout the world. Legendary British Admiral Horatio Nelson called it “the most bold and daring act of the age.” While all these daring deeds were taking place, Eaton was planning a bold stroke of his own. He used the fervor over the capture of the Philadelphia to pitch to the president his own plan for overthrowing Bey Yusef. This time Jefferson was interested, although it is unlikely he was told the full extent of Eaton’s audacious plan. He gave Eaton $40,000, 1,000 rifles, and the dubious title of United States Naval Agent on the Barbary Coast. Eaton added to that sum by withdrawing any remaining funds left over from his land speculation deals.

Eaton Sets Off to Track Down Hamet

With his affairs in order, Eaton set off for the Mediterranean to track down the wayward Hamet.

Inevitably, there were obstacles in Eaton’s path. His plan required a coordinated effort between land and naval forces, but the Navy was not on board with his scheme. The new commander of the American squadron, Commodore Samuel Barron, was doubtful of Eaton’s plan and of Eaton himself. Much of his distrust stemmed from Eaton’s earlier conflict with Commodore Morris. Barron blamed Eaton for endangering the life of a naval officer to pay off his own debts. He also doubted Hamet ‘s ability of raise an effective rebellion against his brother. Eaton argued strenuously with Barron during the voyage to the Mediterranean and managed to wrest a token pledge of support from him but the palpable distrust between the two would continue to plague his efforts.

Hamet was believed to be in Egypt, so Eaton and a handful of marines landed at Alexandria on November 26. They immediately set off down the Nile River for Cairo. The voyage was long, and they didn’t arrive at the city until December 7. When his party finally staggered into Cairo, Eaton and his men were treated like royalty by the Turkish viceroy. Eaton took advantage of the opportunity to grill the viceroy about Hamet’s whereabouts. He eventually learned that Hamet had gotten himself into trouble and was surrounded by Turkish troops at the nearby city of Minyeh. Eaton’s band was too small to mount a rescue operation, but without Hamet, there could be no coup. It seemed as if Eaton’s grand adventure was going to end before it began. Then fate stepped in.

During one of his many tours of the city, Eaton encountered a bizarre character who called himself Johan Eugene Leitensdorfer. Like many Westerners in the Arab world, Leitensdorfer was on the run. Born Gervasio Santuari in Italy, Leitensdorfer had a rather colorful résumé. He was a bigamist, a deserter from multiple armies, and an all-around criminal. Naturally, he and Eaton became fast friends. When Leitensdorfer offered to get a message to Hamet, Eaton accepted. Somehow, the wily Italian managed to penetrate the Turkish lines and returned with a communication from the deposed bey. Eaton and his band of adventurers set off to meet Hamet, but they were detained by a Turkish garrison along the way and charged with spying. Luckily, Eaton’s fluent Arabic and loose purse strings managed to save the day. They eventually reunited with Hamet at the town of Damanhur and began planning their coup.

Unfortunately, Barron’s assessment of the deposed bey proved all too accurate. Hamet was not the dashing figure that Eaton had painted in his reports to Jefferson and the State Department. Instead, he was a sybaritic harem lounger who much preferred a life of ease and comfort to the rigors of the campaign trail. And although he was surrounded by the usual doting sycophants, his actual popularity in Tripoli was questionable. His brief reign had been problematic, and no one back home was clamoring for his return. Eaton, however, saw past his faults. To him, Hamet was a means of finally achieving his lifelong dream of commanding his own army, the prospect of which induced the self-intoxicated Eaton into giving himself the title of general. It was a bizarre beginning to one of America’s strangest military campaigns.

Eaton Builds His Own Army

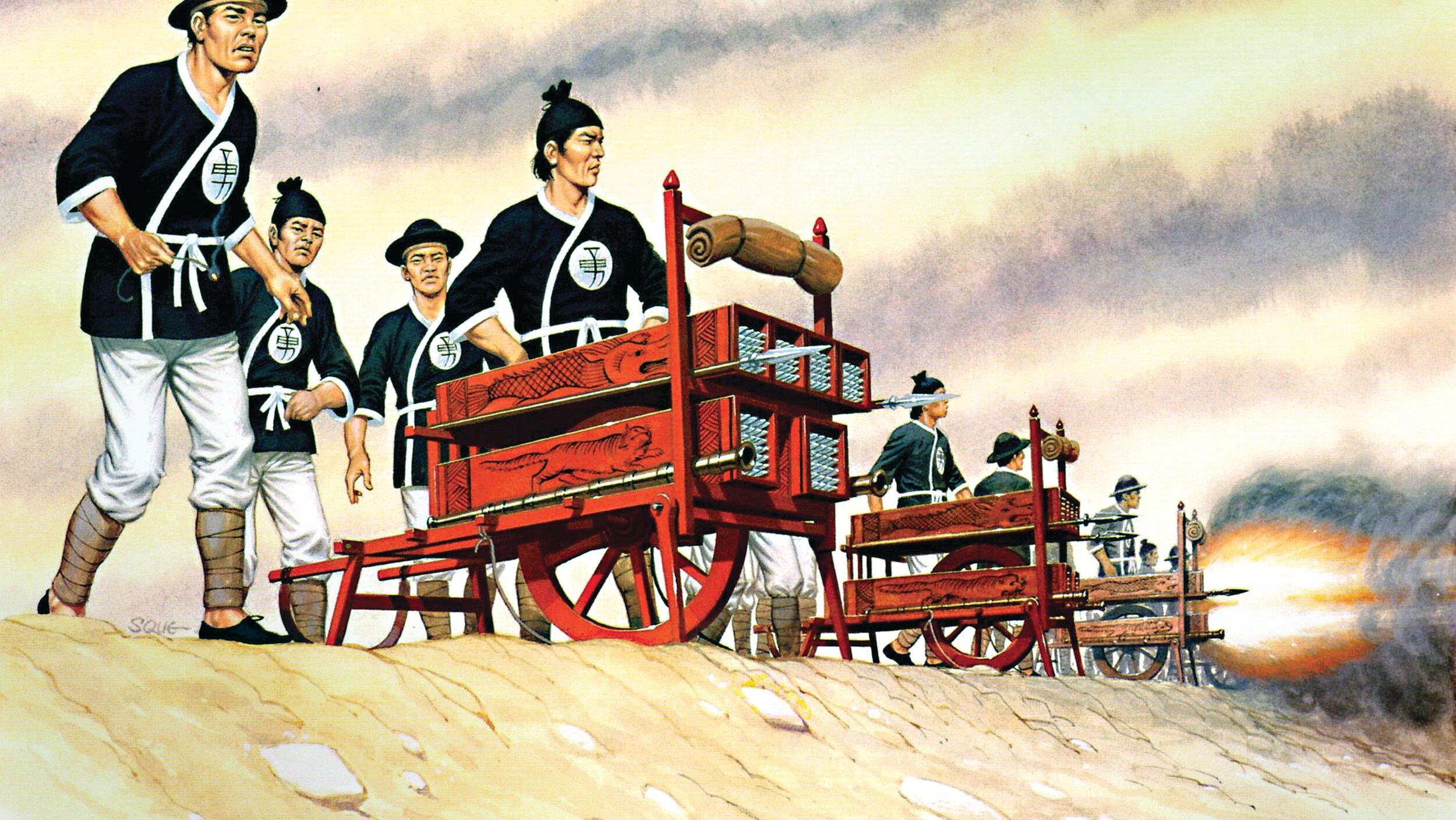

Before he could start his campaign, Eaton needed an army. Hamet had arrived with roughly 100 followers, whose actual fighting ability was dubious at best. Eaton had requested a contingent of 100 marines from Barron, but his request had been denied. This left him with only the eight marines who had accompanied him on his search for Hamet. They were led by an able young lieutenant named Presley O’Bannon who, along with Leitensdorfer, would become one of Eaton’s most valuable commanders. O’Bannon and Eaton immediately set about recruiting mercenaries in Alexandria and soon assembled a rogue’s gallery of Turkish, Greek, French, English, Spanish, Indian, and Eastern European mercenaries.

While Eaton was busy rounding up mercenaries, Hamet was attempting to rally disaffected Tripolitans, Egyptians, and other Arabs to their cause. His efforts met with a modicum of success. Together, Eaton and Hamet managed to amass a force of roughly 400 men. It was not enough to accomplish their lofty goals, but it was a start.

Their polyglot army set out for Tripoli on March 8, 1805. Their first target was Derna, the second largest city in Tripoli. The original plan of attack had been to approach Derna by sea, but Hamet insisted on taking the overland route to remain close to his followers. The overland route to Derna was long and arduous, leading across hundreds of miles of scorching desert populated by hostile Bedouin tribesmen. The expedition was for an ungainly sight as it crossed the desert. Arab cavalry, scores of polyglot mercenary infantry, and nearly 200 camels stretched as far as the eye could see. The varying nationalities made communication difficult, and the equally various religious affiliations threatened to splinter the party along doctrinal lines. It took all of Eaton’s, O’Bannon’s, and Leitensdorfer’s joint efforts to keep the rival groups from killing each other.

On the fifth day, a rider approached Eaton with the welcome news that Derna had revolted in favor of Hamet. The Arab riders at the front of the column immediately began firing their guns in celebration. The noise startled those in the rear of the column, who feared they were under attack by Bedouins. The frenzied European and Arab mercenaries nearly attacked each other in the resulting confusion before Eaton and his commanders managed to regain control and avert a bloodbath. Ironically, the expedition had nearly self-destructed over nothing—the rumors of an uprising at Derna turned out to be false.

A Long, Contentious March to Derna

As the march wore on, both funds and supplies began to run low. It had cost Eaton nearly $100,000 to assemble, equip, and supply his force. That amount was over twice his proposed budget, so he had little left over for contingencies. Two weeks into the march the Arab camel drivers revolted, claiming that they had not been paid for the entire journey. They demanded the rest of their money, or they threatened to abandon the expedition. Eaton’s coffers were dry and he was forced to take up a collection among the marines and other men to mollify them. His efforts were wasted when most of the camel drivers deserted during the night.

Relations between Eaton and the Arabs worsened as the group drew closer to Derna. Rumors that Bey Yusef was sending an army to reinforce the city terrified the Arab cavalry. Their leader, Sheikh El Taiib, refused to continue and had to be repeatedly coerced. The rumor of Yusef’s approaching army became so pervasive that it threatened to destroy the expedition. Even Hamet, the centerpiece of the plan, became so frightened that he refused to proceed. After a heated argument, Eaton took his marines and mercenaries and continued marching across the desert. He hoped that Hamet’s shame at being left behind would overcome his fear of Yusef. The ploy worked, and the deposed bey sheepishly caught up with Eaton a few hours later.

The march to Derna was not all hardship and turmoil. Along the way, Hamet managed to recruit 80 Arab horsemen and 150 infantry soldiers. These forces significantly added to the expedition’s ranks, as well as to Eaton’s growing debt. The motley army began attracting more followers when they finally entered Tripolitan territory. The expedition soon ballooned to over 1,000 people, including baggage train drivers and the families of the Bedouin horsemen.

By April 8, the expedition’s supplies were nearly gone and the Arabs were once again refusing to continue. Eaton argued that American vessels were waiting to resupply them at the nearby Bay of Bomba, but that failed to convince them. Hamet did not help the situation when he announced that he was returning to Egypt. Furious, Eaton ordered that no more supplies be distributed to the Arab cavalry. He hoped that their hunger would compel them to move forward, but it only added to the growing tensions inside the expedition.

These tensions nearly boiled over into outright violence when a group of irate Arabs attempted to storm the supply tent. Anticipating such an action, Eaton had positioned O’Bannon and Leitensdorfer, along with the marines and other non-Arab mercenaries, in front of the supply tent. Both groups stared at each other with weapons drawn. The vastly outnumbered mercenaries held their ground, although they knew that the slightest provocation would result in a massacre. Eaton nearly provided that provocation when, in his usual blunt manner, he began insulting the Arabs and claiming that they were afraid to fight. He hoped that his taunts would shame them into backing down, but it nearly resulted in catastrophe. It wasn’t until Hamet rode between the two groups and announced that he was staying with the expedition that cooler heads prevailed.

The Battle for Derna

The expedition reached Bomba a few days later and was resupplied by the waiting American vessels. After a week of rest, Eaton and his army set off to cross the final 60 miles to Derna, a city of roughly 10,000 inhabitants that was defended by a garrison of 800 troops. It would be a tough nut for Eaton’s force to crack. The expedition took up positions outside the city on April 26 and prepared for battle. Eaton attempted to avoid a conflict by writing to the governor of the city and offering him a position in Hamet’s new government if he would resupply the expedition and allow it to pass through Derna unmolested. Eaton concluded the letter with the line, “I shall see you tomorrow in a way of your choice.” The governor’s response was brief and to the point: “My head or yours.”

Although storming the city was going to be difficult, Eaton was excited. This was the moment he had dreamed about since he was a boy. Hamet, on the other hand, was not pleased—the thought of assaulting a fortified city terrified him. Adding to his fear was the rumor that Yusef had dispatched a 1,200-man relief force to Derna. Eaton snidely remarked that Hamet “wished himself back in Egypt.” Eaton’s plan called for a two-pronged attack. An assault force of 60 marines and mercenaries, led by O’Bannon, would attack the city’s barricades while Hamet and 200 Arab horsemen attacked the city from the south. The rest of the Arab cavalry would remain to the south of the city to act as a reserve and prevent any relief forces from reaching Derna. The operation would be assisted by covering fire from three American vessels: Argus, Hornet, and Nautilus.

The battle began the next morning when Derna’s shore batteries fired at the American vessels in the harbor. The ships responded with broadsides and soon the air was filled with cannon and musket fire. The opening rounds of the battle went well for Eaton’s forces. The American ships succeeded in silencing the shore batteries, and Hamet’s Arabs managed to capture an old castle on the outskirts of the city. However, O’Bannon’s strike force was pinned down under heavy fire from the city’s defenders. Eaton knew that the undisciplined mercenaries would flee if something wasn’t done immediately. In typical grandiose fashion, he decided to charge.

Amazingly, even though the defenders outnumbered the attackers by nearly 10-to-1, they retreated in the face of Eaton’s audacious assault. The strike force stormed the barricades and took possession of the shore batteries.

Eaton was shot in the left wrist during the assault but still managed to raise the American flag above the fort at the Derna harbor. It was the first time in history that the Stars and Stripes had flown over foreign territory.

Eaton’s men aimed the fort’s cannon toward Derna and joined the American warships in shelling the city. Hamet’s force pressed the assault from the south and managed to capture the governor’s palace. With the fall of the palace, all resistance ended. The battle to capture the city had been brief, lasting only two and a half hours. It had also been relatively painless, claiming the lives of only two Marines.

The battle to hold the city, however, had just begun. It turned out that Hamet’s fears of a relief force were well founded. An army sent by Yusef was only a few days’ march away.

The anticipated attack came on May 13 when Hassan, the commander of Yusef’s relief column, led 1,200 men against Derna. They overwhelmed an outpost defended by Hamet’s Arabs and rapidly closed in on the city. Eaton pointed the guns from his newly renamed Fort Enterprise toward Hassan’s attacking column. Their withering fire, along with broadsides from the American ships, managed to drive back the attackers.

Eaton’s capture of Derna would become one of the most celebrated victories in American military history. It inspired the famous second line of the “Marine Corps Hymn.” The saber that Hamet awarded to O’Bannon after the battle became the model for all subsequent Marine officers’ swords. The victory was also lauded in “Derne,” a popular if not particularly accomplished poem by John Greenleaf Whittier that included the following bombastic stanza about Eaton:

“Dark as his allies desert-born,/

Soiled with the battle’s stain, and worn/

With the long marches of his band

Through hottest wastes of rock and sand,

Scorched by the sun and furnace-breath/

Of the red desert’s wind of death,/

With welcome words and grasping hands,/

The victor and deliverer stands!”

Yusef Attempts to Recapture Derna

When news of Eaton’s victory reached Tripoli, Yusef understandably grew worried. With American ships blockading his harbor and Eaton’s forces approaching from the east, he was in an unenviable position. Yusef immediately resumed peace negotiations with the Americans. However, he also continued to dispatch reinforcements to the relief column outside Derna. By June, Hassan’s army had grown to almost 5,000 men. On June 11, he renewed his assault on Derna.

This last engagement was a savage duel between Hassan’s men and Hamet’s Arab cavalry. The deposed bey carried himself well throughout the ordeal, bravely leading his men in repeated attacks and counterattacks.

Eaton watched the battle unfold from the battlements while he prepared the city’s defenses. After four grueling hours, Hamet finally managed to drive off Hassan’s forces. His courage under fire had finally justified Eaton’s continued faith in him. Unfortunately, it came too late to save the expedition.

Eaton’s Grand Expedition Comes to an Inglorious Conclusion

Unbeknownst to the combatants at Derna, Yusef had finally bowed to the growing pressure and signed a peace agreement on June 3. He even agreed to release the captive crew of the Philadelphia. The war was over, and Eaton was ordered to evacuate Derna. The thought of abandoning the men that he had just led across 520 miles of scorching desert was unthinkable to Eaton. He knew that Hamet and all of his followers would be slaughtered once the Americans pulled out, and in a charcteristic display of stubbornness he refused to leave.

Anticipating Eaton’s refusal, the American squadron had already dispatched the Constellation to bring him home. When the ship arrived with explicit orders to evacuate Derna, Eaton knew that his cause was lost. He was low on supplies and equipment, and he had no hope of continuing the expedition without American support. His dreams of conquest shattered once again, Eaton grudgingly agreed to leave.

The evacuation had to be kept a secret from the inhabitants of Derna; if they found out they were being abandoned, they were liable to rise up and slaughter Eaton and Hamet in righteous anger. Additionally, if Hassan’s army outside the walls learned of the withdrawal, they would descend on the city before the evacuation was complete and slaughter the company.

To distract the city’s inhabitants, Eaton ordered them to prepare for a counterattack against Hassan. While they were girding for battle, Eaton ordered the Marines, the Christian mercenaries, Hamet, and a few of his followers into the Constellation’s lifeboats. Under cover of darkness they rowed silently into the harbor toward the waiting ship.

Their trickery was soon discovered, and the city’s inhabitants rushed toward the docks in fear and outrage. Eaton watched the scene unfold from his lifeboat with a heavy heart. “The shore, our camp and the battery were crowded with the distracted soldiery and populace,” he recalled, “some calling on the Bashaw [Hamet]; some on me; some uttering shrieks; some execrations.”

Constellation slipped out to sea the next day, bringing Eaton’s grand expedition to an inglorious conclusion. Nevertheless, “General” Eaton was welcomed back to America as a conquering hero. Newspapers lauded him and he was invited to celebrations by President Jefferson and a host of leading politicians. For a time, his name was whispered breathlessly alongside such legendary conquerors as Caesar and Alexander the Great. This hyperbole soothed his wounded ego, and Eaton soon returned to his blustery old self. He began loudly condemning the treaty that had forced him to abandon Derna. His opinions were widely published, which did little to ingratiate him with the Jefferson administration. Jefferson’s enemies soon took up his cry and Eaton found himself caught up in partisan battle that left him with few friends in Washington.

The Final Straw: The Burr Fiasco

As time went on, Eaton’s outbursts grew louder and more vitriolic. He began drinking heavily and was seen roaming the streets of Washington in Bedouin robes. In the eyes of many, the great conqueror of Derna had degenerated swiftly into a comic figure. At this low point, Eaton became involved in the oddest and most damning chapter of his life. He was approached by Aaron Burr, the long discredited victor of the legendary duel with Alexander Hamilton, to join in a plan to invade the Spanish territories in the Southwest. Burr needed prominent military men to give his campaign credence. Eaton was no longer a vaunted celebrity, but his name could still lend an air of respectability to Burr’s outlandish plan.

Eaton initially embraced the idea. The thought of reprising his glory at Derna was too much to resist. However, Burr’s plan went beyond a simple invasion of the Spanish territories. He also planned to move against American territories and, if possible, Washington itself. This was too much for the “General.” Eaton may have been a braggart and a drunk, but he wasn’t a traitor. Despite the bad blood between himself and the president, he returned to Washington and personally informed Jefferson of Burr’s plan. His warning fell on deaf ears.

Jefferson had been personally hurt by Eaton’s slurs, and he coldly had his visitor shown the door. Burr’s traitorous activities eventually caught up with him, and he was tried for treason in 1807. Eaton was called to testify and Burr, a brilliant trial lawyer, conducted the cross-examination himself. He used Eaton’s earlier court-martial and numerous other problems to impeach his credibility. By the time Eaton stepped down from the witness stand, few people believed his claims. Burr’s ultimate acquittal only added salt to the wound.

The Burr fiasco was the last straw for Eaton. He retreated into virtual isolation in Maine and drank himself into a stupor. His health deteriorated rapidly, and he finally succumbed to drink, depression and illness on June 1, 1811. Eaton’s strange, sad life was summed up in a brief obituary by the Massachusetts Columbian Sentinel:

“General Eaton, the hero of Derna and the victim of sensibility, was entombed at Brimfield on Wednesday last.” A quarter of a century later another New England newspaper, the New Hampshire Patriot & State Gazette, gave a more jaundiced view, one that Eaton probably would have endorsed wholeheartedly. The erstwhile adventurer, said the paper, had been “a victim of the ingratitude of his country.”

Am teaching a course on William Eaton to continuing learning adults at Furman University’s OLLI courses.. Emphasis on Lt of Marines Presley O’Bannon. Your info useful as was “To The Shores of Tripoli” by A.B.C. Whipple and US Archives along with Naval History-The Barbary Wars.