By Robert Barr Smith

Near Marseilles, at Aubagne, stands the modern home of the French Foreign Legion. Its spotless grounds include a massive stone pile, the Monument aux Morts, which commemorates the Legion dead of the past 175 years. When the Legion left its spiritual home, Sidi-bel-Abbes, Algeria, in 1961, the monument was dismantled stone by stone for the return to France. At the same time, the Legion’s treasured mementos were tenderly brought back to new places of honor in the organization’s crypt and museum.

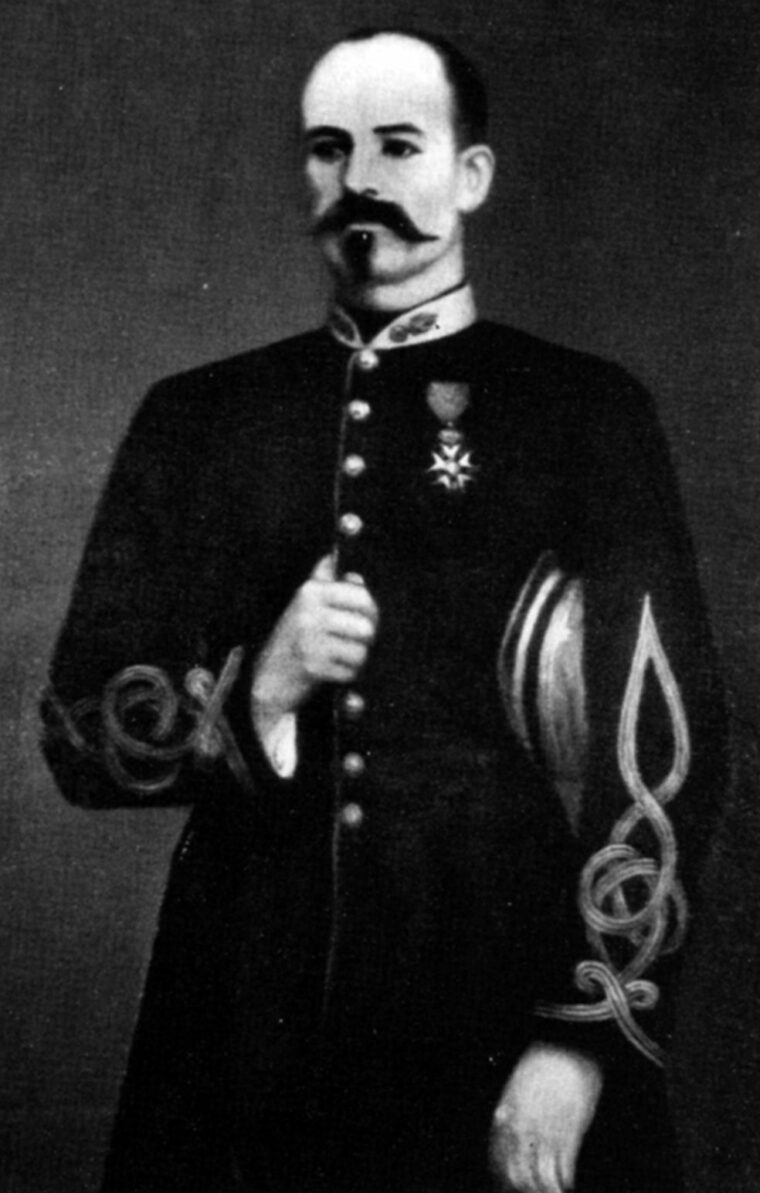

These mementos represent an immense military tradition, a tradition of absolute loyalty, unswerving courage, and contempt for death. There are medals, swords, and pictures, and the flags of the Legion are dripping with more decorations than any other unit in the French Army. Most curious of all, there is a little wood-and-glass casket containing a simple wooden hand. The hand belonged to Captain Jean Danjou, a 35-year-old officer whose left hand had been lost in the service of France at the Battle of Sevastopol. A St. Cyr graduate and a veteran of desperate fighting in Algeria, the Crimea, and the slaughterhouse of Magenta, Danjou still had his saber hand, and he had equipped himself with a wooden hand, articulated and finely sculpted. Strapped to his wrist with a large leather cuff and sheathed in a formal white glove, the hand was sufficient to manage his horse’s reins. He was a legionnaire, after all, and the Legion had always made do with less.

Today, Danjou’s wooden hand lies in state in its little casket at Aubagne, the most sacred talisman in the Legion, and it is shown with reverence to new recruits, who in time come to understand what it means. For to understand the meaning of Danjou’s hand is to understand the mystique of the French Foreign Legion, its incredible courage and sublime contempt for danger. Danjou’s hand demonstrates that defeat is not part of the Legion vocabulary. Men may die and units may be destroyed, but the Legion itself is never whipped. That defiant philosophy is encapsulated in the wooden hand and the battle it commemorates—Camarón.

Napoleon III’s Adventurism in Mexico

In the spring of 1863, Camarón was a dreary village in eastern Mexico on the fever-haunted road connecting Veracruz and the French fleet there with Puebla, on the Mexican plateau. At Puebla lay the French Army, still trying to win an empire for Napoleon III and his Habsburg puppet, Maximilian, younger brother of Emperor Franz Joseph. The French intervention had begun as an attempt to recover interest payments on large loans from several European nations on which the Mexican government had defaulted. Foreign troops had occupied several Mexican ports, promising President Benito Juarez that they would keep out of Mexican political affairs. All but the French soon saw the futility of the effort and went home. But the French, hungering for empire and determined to put the Austrian prince on the throne of a faraway country in name of French banks, held out.

Napoleon III was a pale imitation of his formidable namesake. He saw the Mexican default as a chance for both military glory and a renewed French foothold in the new world. It was a harebrained notion, and both Franz Josef and the British government advised against the adventure. Besides the difficulty of campaigning in Mexico, it was clear to the unbiased observer that the United States would never tolerate a European power ruling part of the Western Hemisphere. The American Civil War would be over in time, and two of the finest armies in the world—the Union and Confederate Armies facing each other in the field—were both American.

But Napoleon III and Maximilian would not listen. The French Army, hammering away at Mexican defenders at Puebla, needed regular supplies from its beachhead at Veracruz. The critical road along which the supplies came was guarded by the Legion, scattered in pockets along the desolate route from the sea. The road was miserably bad, holding a convoy’s progress to eight or 10 miles per day, and the settlements along the way were a series of disease-ridden pestholes. It was terrible duty, the isolated Legion companies stewing in the heat, fighting off Mexican raiders, dysentery, and malaria, as well as the terrifying disease called vomito negro, or black vomit, but formally known as yellow fever. And then there was le Cafard, that sudden craziness that made men go berserk, named for the black beetle said to crawl into a man’s brain after too much drink or sun and drive him to run screaming and drooling like a rabid animal, or else fall on his bayonet for relief. It was born in the miserable little forts of North Africa, and now it thrived in Mexico, brought on by too much pulque and mescal, the local drinks of choice.

The Legion Prepares for a Fight

One night at the end of April 1863, an Indian spy brought word to Legion Colonel Pierre Jeanningros that the next convoy would be attacked by powerful Mexican forces, including regular troops. The convoy was a large one—60 carts and 150 mules—and it was critical, carrying not only food and ammunition but also four million francs in gold and badly needed artillery. The convoy would need help along the road, and that help could come only from the Legion.

Jeanningros had few troops of his own to send. In addition to the convoy’s small escort, he could spare only a single company, the 3rd Company of the Legion’s 2nd Battalion, already down to half strength. But the colonel could send the experienced Jean Danjou as its commander. The captain would have two other officers to help him, both second lieutenants. One, Napoleon Vilain, was a boyish ex-enlisted man; the other, Clement Maudet, was an old sweat who had risen through the ranks to sergeant-major before winning his commission.

Danjou commanded 62 NCOs and enlisted men from all over the world. There were Belgians, Swiss, Germans, Frenchmen, Poles, Dutch, and Danes. It was a typical Legion company, fiercely loyal to the Legion, its officers, and each other. Shortly after midnight on April 30, Danjou set off down the so-called fever road to cover the convoy, passing through a series of thoroughly forgettable hamlets without meeting the enemy. The company passed in peace through miserable Camarón, an unattractive village “inhabited by vultures,” someone said, and marched a little farther.

Shortly after daylight, at a halt to refill its canteens with water and make a little coffee, the company saw its first Mexican cavalry. Danjou reacted instantly, falling back toward Camarón to cover the all-important road. He was fired on from a dilapidated hacienda in the village, a place called Hacienda La Trindad, and a legionnaire was wounded. And then Danjou saw hundreds of Mexican cavalrymen. The company formed a hollow square, and its disciplined volley firing twice broke Mexican charges, littering the ground with fallen horsemen. Danjou knew that he must find cover—the enemy was far too strong to take on in the open. He ordered a retreat into Camarón.

The force took shelter in a stable building next to the run-down hacienda, surrounded by a 10-foot wall. In the wall were two gates, plus another opening, and Danjou gave orders to plug the gaps in his little fortress. The main hacienda building was already occupied in strength by Mexican troops, and Danjou posted his men at windows and walls in the stable enclosure and had his troops break loopholes in the thick walls. From the improvised fortress, the legionnaires could cover any attempt to rush them. Danjou’s men used rocks and rubble to plug doorways and breaches in the walls, and settled down for a siege. The day was already breathlessly hot.

Danjou’s little company was an interesting bunch: Corporal Evariste Berg was an ex-officer and winner of the Legion of Honor, cashiered from the army for misconduct. He had then enlisted in the Legion, which cared little about such things as cashiering or, indeed, about anything in a man’s past. Then there was Louis Maine, a veteran of the Crimean fighting and also a holder of the Legion of Honor, who had given up his sergeant’s stripes to enlist in the Legion. Sergeant Vincent Morzycki was a veteran of the Italian fighting, the son of a French mother and a Polish officer.

The Battle of Camarón Begins

Danjou’s men began to take casualties early from the heavy Mexican fire. They returned it, firing carefully and choosing their targets. Not only is fine fire-discipline a Legion tradition, but the Legion pack-mules had bolted at the first Mexican charge, taking with them the reserve ammunition. Danjou’s men had only the 60 cartridges each carried in his pouch. To make matters worse, the legionnaires were also low on water, most of which had vanished with the frightened mules. None was available in the building they were to hold. The company had to endure the horrors of thirst in the oven-like enclosure. It was especially horrible for the wounded. Before the day was over, they would be reduced to licking the blood from their own wounds for moisture. At 9:30 am, the Mexican commander sent in a flag of truce and offered the legionnaires the chance to surrender. Danjou scornfully refused.

The murderous fire continued, and the legionnaires continued to drop. Their own disciplined fire inflicted heavy losses on the Mexicans, but there seemed to be no end to the attackers. Danjou, old professional that he was, could read the signs. He ordered his German batman to bring him his daily liter of wine, carefully carried all night and morning. To each man Danjou gave a sip of the raw pinard, and required each soldier to swear an oath to die rather than surrender. Each man swore, and before the end of the hellish broiling day, each man would keep faith with this strange communion. “Legionnaires die better than any men in the world,” Danjou said with a certain proud fatalism.

Casualties Mount

A little while before noon, Danjou kept his own rendezvous with destiny. He was running from one building to check a detachment behind a barricade when a sniper’s bullet hit him in the chest. He lived only moments. Young Lieutenant Vilain got to him; Danjou tried to speak but could not. Then he was still. Vilain took command of the 40 remaining men and fought on, declining another chance to surrender with the typical Legion oath: “Merde!” For a little while, at noon, there was a flash of hope. Drums could be heard in the distance, along with bugles. The company for a moment thought it was a French relief column, but the music turned out to be Mexican; soon, another 1,000 infantry surrounded them.

Vilain was killed as he, too, crossed the open area to check on his men. Maudet, the ex-sergeant-major, took command of the pitiful little band that remained. Nearly everyone was wounded by now, and the barrels of the long Le Gras rifles were far too hot to touch. The heat was nearly unbearable; the wounded were in agony, and one by one the survivors went down into the dust. Those still able to shoot emptied the cartridge pouches of the dead and wounded. And still their deliberate rifle fire held back the attackers and dropped them by the score.

Legionnaire Maine later recalled the hellish conditions at Camarón: “The heat pressed on us; the sun struck from the white walls of the courtyard, searing our eyes. When we opened our mouths to breathe, we seemed to inhale fire.” At last, nearly all the blue-coated soldiers lay still in the dirt. Only five remained standing—the hard-eyed Maudet, husky Corporal Maine, and three privates. They were down to one last cartridge apiece, and Maudet looked around at the remnants of his little command. He gave his last orders, and his men nodded. They fired a last volley together and then they followed him with their bayonets into the howling mob of Mexicans drawing ever closer.

As they charged into the blazing sun, a blast of Mexican fire stopped the legionnaires in their tracks. A Belgian legionnaire named Catteau stepped in front of his officer and took 19 bullets intended for Maudet. Even so, Maudet went down too, along with one of the privates. Their ammunition was entirely gone, but their luck held. The mass of Mexicans was halted by their officer, a French-born colonel named Combas, who blocked his men’s bayonets with his sword blade and called on the legionnaires in French to surrender. Maine, the ranking officer, agreed, “if we keep our arms and you care for our officer.” Combas answered, “One refuses nothing to such men as you.” His superior, Colonel Francisco de Paula Milan, wanted to know where the others were. “There are no more,” said Combras. “Pero, no son hombres, son demonios,” said Milan. “Then these are not men, but devils.”

Camarón: The Legend

Thus ended the stand at Camarón, 11 hours in the blazing sun, during which the legionnaires had fired almost 4,000 rounds and left at least 300 of their enemy dead or wounded around them. In return, 39 legionnaires lay dead in the hacienda. The terrible heat and wounds would kill most of the rest, including Maudet, despite Mexican attempts to save them. The few survivors passed into captivity and were later exchanged for Mexican prisoners. The convoy would go through untouched.

The relief column, which arrived at Camarón much too late to rescue any of Danjou’s legionnaires, buried their dead comrades in a common grave. Danjou’s wooden hand was picked up by a local rancher, who kept the thing as a sort of souvenir for a couple of years before selling it back to General Achille Bazaine, the French commander in Mexico, himself a one-time Legion officer.

The disaster at Camarón would become a Legion legend, symbolizing everything that made the organization both different and great. April 30 remains the high holy day of the Legion, Camarón Day, when legionnaires are forgiven virtually any transgression short of murder, and the great deeds of the past are celebrated with much ceremony. In 1931, General Paul Rollet, called the father of the Legion, institutionalized Camarón Day in a large formal ceremony at Sidi-bel-Abbes. There was a march-past, led as usual by the Legion’s bearded sappers, followed by speeches and a solemn parade of Danjou’s hand. At the Monument aux Morts in Aubagne, the Legion still parades, and some highly decorated former legionnaire has the honor of bearing Danjou’s hand. The entire Legion stands in ranks while an NCO reads the story of Camarón. The same ceremony is repeated wherever the Legion is stationed.

“Camarón” has become a verb as well as a noun. “To Camarón” has come to mean making a last stand against enormous odds, with little hope of survival. One of the surviving Legion officers used the phrase at the bitter end of the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, when the commanders in the valley considered whether to surrender or try to break out. “You can do a Camarón with a hundred guys, but not with ten thousand,” they reasoned, opting to surrender—something the defenders of Camarón never did.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments