By John Walker

It began with the now-familiar sound, like thunder, coming from the hills to the northeast of the entrenched camp, as hidden Viet Minh mortar and artillery sites began raining destruction down upon the French fortifications in the Dien Bien Phu valley. The commander of the insurgent People’s Army, General Vo Nguyen Giap, had chosen this night, March 30, 1954, to unleash the second major phase of his ground attacks—and the first actual assaults upon the main camp itself—against the multiracial French Far East Expeditionary Corps (CEFEO) garrison, consisting of about 12,000 men, waiting behind minefields and barbed wire in their frail blockhouses, bunkers, and trenches.

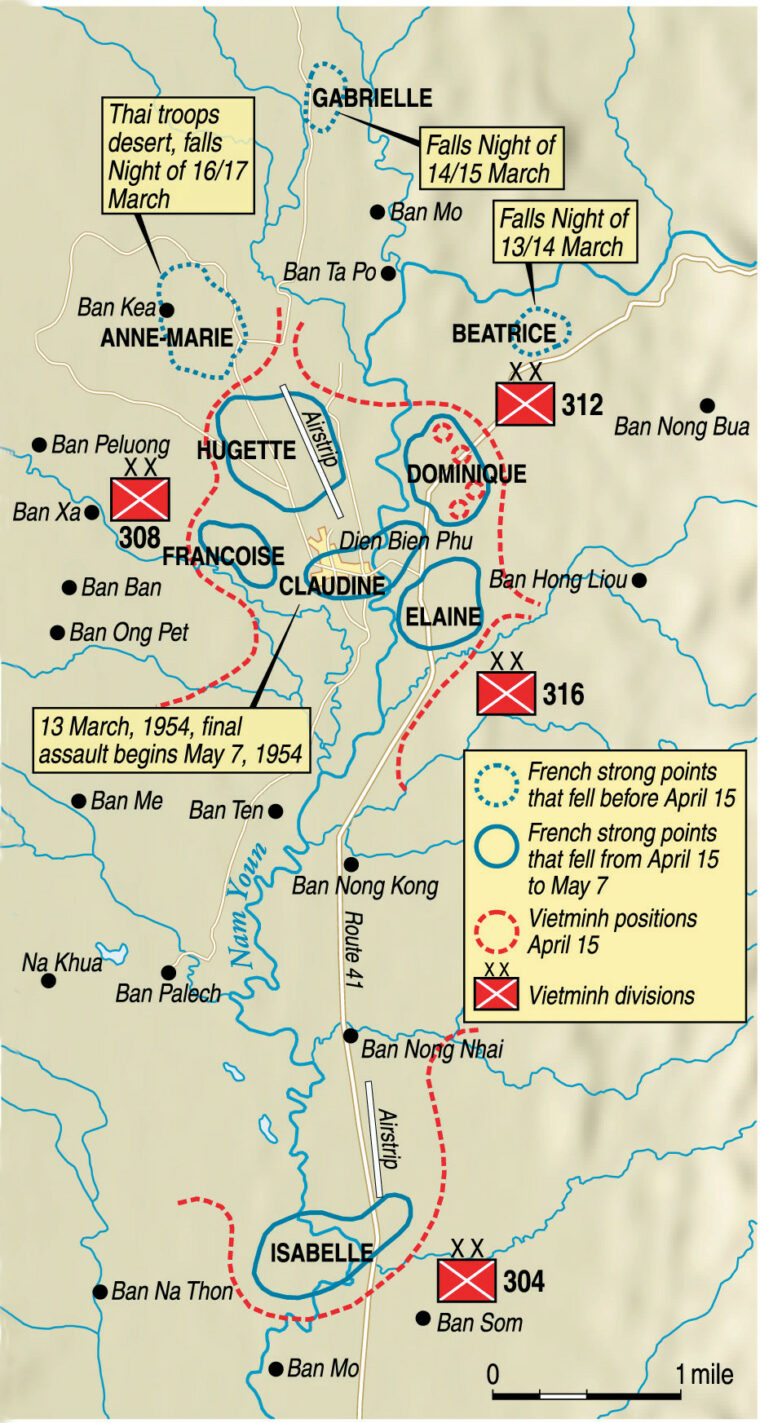

Giap’s objective was an ambitious one. After weeks of shelling from ingeniously constructed artillery emplacements in a network of manmade caves sunk into the hillsides facing Dien Bien Phu, he was about to commit five full regiments of well-trained and well-equipped regulars in an all-out, simultaneous strike against the fort’s entire eastern defensive perimeter. By doing so, he hoped to capture five strategic hill outposts—Dominique 1 and 2 and Eliane 1, 2, and 4—along a north-south front three quarters of a mile long. A diversionary attack would be mounted along the fort’s northwestern perimeter against the isolated strongpoint Huguette 7, far to the west of the camp’s destroyed, unusable airfield. Once the hills were captured, the way would be clear for a final assault on the base itself. The fate of Vietnam hung in the balance.

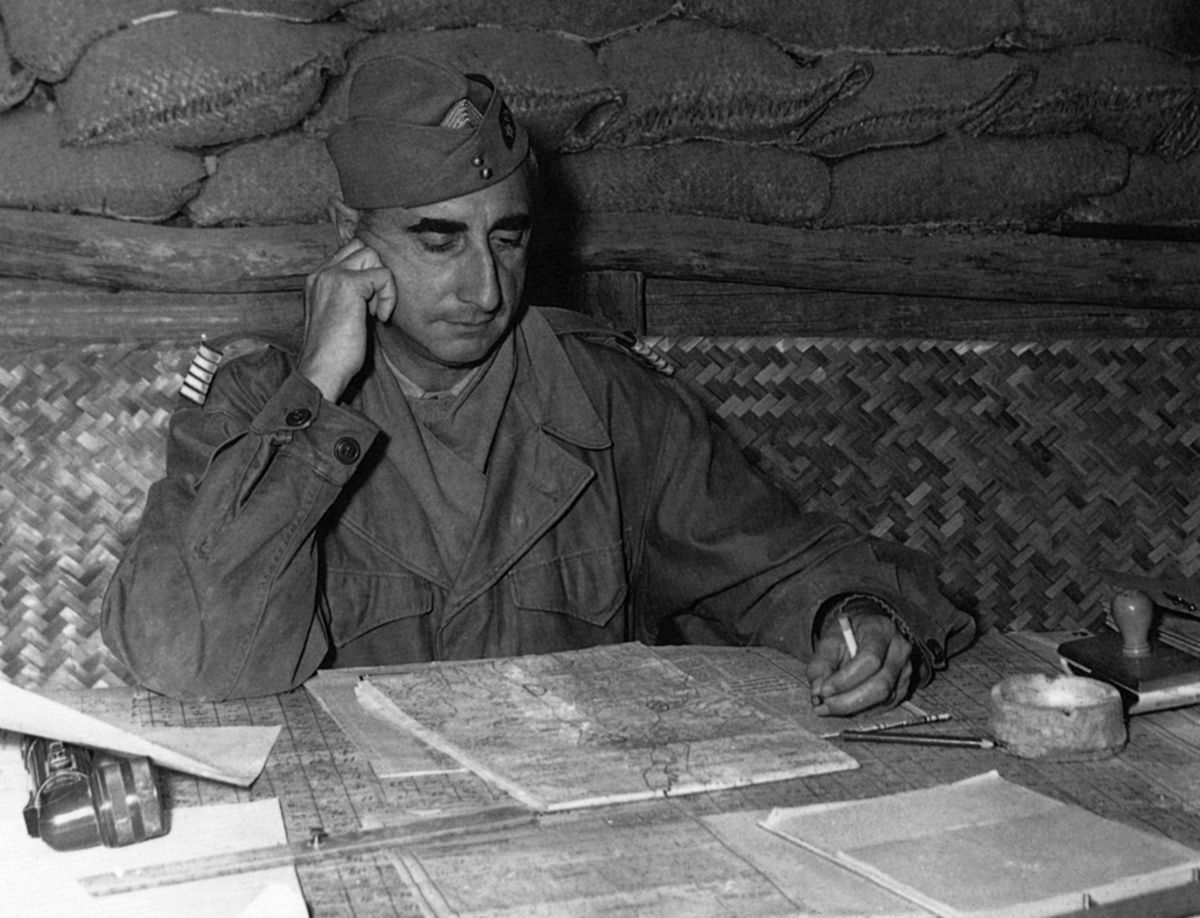

The French garrison, made up of Frenchmen, Algerians, Moroccans, French Foreign Legionnaires, enlisted Vietnamese, T’ai tribal partisans, and a small unit of West Africans, had been forced into a precarious defensive situation. Its only hope for victory was that the combined firepower of French artillery and airplanes would be sufficient to destroy the massed concentrations of Viet Minh infantry as they entered the valley, the same way the insurgents had been defeated at Na San in late November 1952. Lt. Col. Pierre Langlais, a respected and aggressive paratroop officer, was the entrenched camp’s central sub-sector commander, but in reality had already assumed overall command. The garrison’s commander, Colonel Christian de Castries, had withdrawn to his command bunker during the night of March 13, the first night of the enemy’s preliminary ground assaults, and had in effect turned over responsibility for tactical decisions to Langlais and another paratroop officer, legendary Major Marcel “Bruno” Bigeard, commanding officer of the elite 6th Colonial Parachute Battalion. De Castries confined himself to dealing with logistical matters and maintaining daily contact with his direct superior, Brig. Gen. René Cogny, commander of land forces in North Vietnam, the most prestigious and important theater command in Indochina.

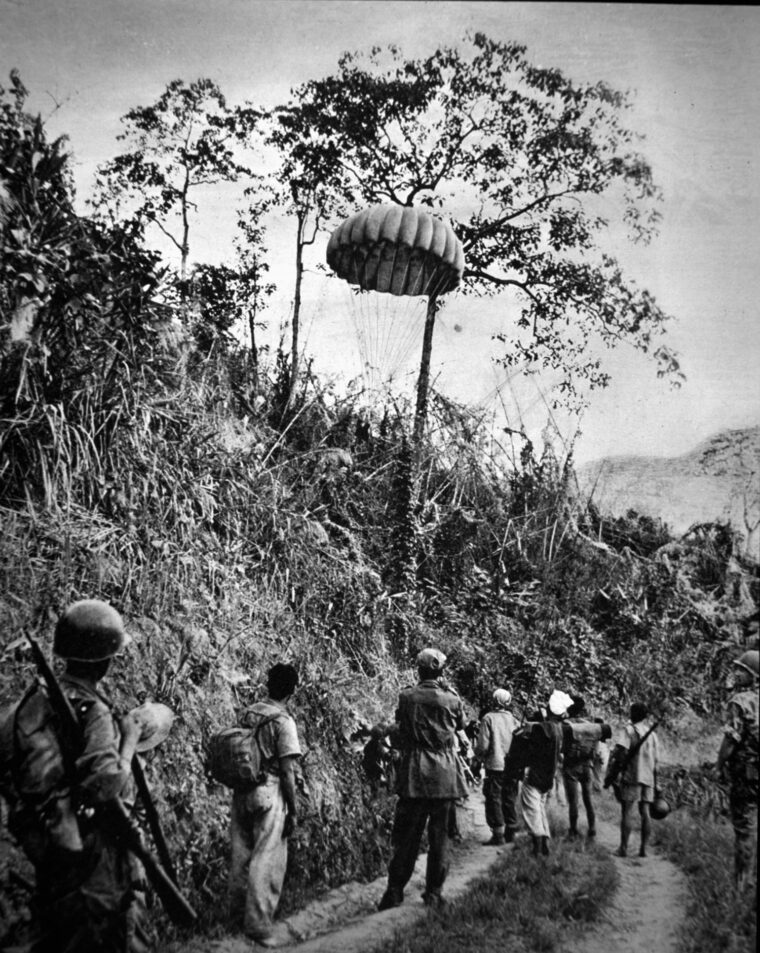

Anticipating an attack, Langlais moved to back up the five hills with added firepower and deployed counterattack units on both sides of the Nam Youm River. Unhappily, Langlais realized immediately that he did not have nearly the numbers of men needed to fill his reserve units. Since the first attacks on March 13, the French garrison, dubbed Operational Group North-West, or GONO, had already lost the equivalent of four infantry battalions in killed, wounded, and missing, and reinforcements being parachuted in piecemeal could not keep up with the casualties. Also, three battalions of able-bodied troops were being wasted at the satellite strongpoint Isabelle, a dismal patch of marshes and swamp six miles to the south, which functioned well as an artillery base but whose garrison soon would be permanently cut off from the main camp by large concentrations of interdicting Viet Minh troops. By early March 1954, after losing both the war of logistics and the ensuing battles for the hill lines encircling the valley, GONO, although stiffened by the finest paratroop and Foreign Legion battalions in all of Indochina, was both outnumbered and outgunned at least three-to-one.

It was not supposed to be this way. When the new French commander in Vietnam, Lt. Gen. Henri Navarre, arrived in-country in May 1953 to assume command of the CEFEO, he immediately began formulating a strategy for luring the elusive Viet Minh forces into a stationary battle of annihilation. Operation Castor, as it came to be known, called for a massive parachute drop of 15,000 French forces into the Nam Youm valley of northwestern Vietnam, near the Laos border. By occupying and fortifying the abandoned Japanese World War II-vintage airbase at Dien Bien Phu (Vietnamese for “big frontier administration center”), Navarre hoped to entice the Viet Minh to attack him there, where French air power could tip the balance decisively against the ragtag peasant army. As Navarre’s subordinate, General Cogny, put it, “I look forward to a Viet Minh assault. Certainly, their artillery will be bothersome for a while, but we will silence it. Since Giap is unable to move into Laos in force through fear of an obstacle rising up behind him, he finds himself forced to attack.”

Giap obliged the French, but only on his own terms and at his own pace. The Viet Minh’s fundamental principle of war, as formulated by Giap and Communist Party chief Ho Chi Minh, mandated: “Attack with a sure blow, advance at a steady pace. If we are sure to win, fight to the end; if not, resolutely refuse combat.” Giap had followed that precept to a number of victories since the Viet Minh began fighting the French in 1946; he had also suffered setbacks, of which the stinging defeat at Na San in late 1952 was a painful reminder to stick to that primary injunction. But Giap had also learned a valuable lesson at Na San: to successfully attack a fortified French airbase, it was necessary first to take and hold the high ground around it, and to patiently and relentlessly degrade the air strip itself, thus cutting off the enemy from reinforcement and resupply. To do so at Dien Bien Phu, Giap needed to amass a large number of ground troops, as well as artillery, and to create and maintain a 300-mile-long line of supply by stockpiling food and ammunition weeks in advance. Only after the French had been suitably weakened would he attack in force. It seemed a simple enough plan—at least in retrospect—but it came only after Giap had subjected himself to a long and painful process of “revolutionary self-criticism” after Na San.

The French—or more accurately, the topography around Dien Bien Phu—obliged Giap beyond his wildest dreams. To protect the vital airstrip in the center of the Nam Youm valley, the defenders had to stretch their forces dangerously thin. There were too few troops to maintain an airtight perimeter defense, so the French decided on the concept of centers of resistance, or CRs, localized strongpoints that theoretically would be able to resist direct attacks by providing mutually interlocking fields of fire. To preserve these CRs, it was absolutely crucial to hold the high ground on the eastern flank, where a series of hills, known collectively as the Five Hills, rose an average of 130 feet above the valley floor. Crack French paratroop battalions were placed on the hills, codenamed Dominique 1 and 2 and Eliane 1, 2, and 4. Behind them, across the 30-yard-wide Nam Youm River, the main French camp sprawled behind a chaotic welter of barbed wire and sandbags.

Strongpoint Dominique was too spread out, almost two miles long and one mile wide, to be held by its understrength garrison of three companies of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Algerian Rifle Regiment, who were tired, ragged, homesick, poorly equipped, and short of seasoned officers and NCOs. The spirit of the Algerians had plummeted after the tragic events of March 14, the second night of the siege. Some 800 of their countrymen in the 5th Battalion, 7th Algerian Rifle Regiment were posted on strongpoint Gabrielle, one of three outworks on the fort’s northern front and the most sturdily constructed redoubt in the valley. After heavy fighting that raged all night, Gabrielle was overrun and the Algerian garrison virtually destroyed. Langlais was alarmed to find Dominique 1, the northern anchor of the eastern perimeter, defended by just one company of 90 Algerians, although they were backed by French Foreign Legion mortar crews. Langlais ordered them replaced by a company of paratroopers of the 5th Vietnamese Parachute Battalion, the only regular unit of Vietnamese soldiers from the non-Communist national army that was present in the valley.

Southeast of Dominique 1, across a 1,000-yard gap through which Route Provinciale 41 (RP41) entered the valley, was the highest of the five hills, Dominique 2, rising 180 feet above the valley floor. Present on D2 were the headquarters and two companies of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Algerian Regiment, under the command of Captain Jean Garandeau. On the southern edge of RP41, between the two hilltop Dominiques, lay the small, lonely outpost Dominique 6. In some hillocks to the south of D2, guarding the gap between D2 and Eliane 1, lay another small outpost, Dominique 5. A thousand yards southwest of where D6 bordered RP41, in the flatlands near the Nam Youm, stood Dominique 3; it was home to four 105mm howitzers manned by West African gunners in Lieutenant Paul Brunbrouck’s 4th Battery, 2nd Battalion, 4th Colonial Artillery Regiment. Providing infantry protection to the battery was a company of Algerian riflemen from the 3rd Regiment.

On the west bank, between the river and the southern end of the airstrip, Langlais established a new outpost, Epervier, to back up the Dominiques; it became home to the better part of Captain Pierre Tourret’s 8th Parachute Assault Battalion, also known as the 8th Shock Battalion. Close by, in an old drainage ditch that paralleled the Japanese-constructed airstrip, several units of the 2nd T’ai Battalion were dug in. Two lethal Browning M2 50-inch machine guns, known as quad-.50s, were placed on elevated mounts, aiming to the east. The Elianes were manned by fairly well-regarded soldiers of the 1st Battalion, 4th Moroccan Rifle Regiment, as well as more paratroopers of the 5th Vietnamese Parachute Battalion. Eliane 1 was just 1,000 yards south of D2 and held one company from the 4th Moroccan Rifle Regiment; another 500 yards to the southwest was Eliane 4, home to the headquarters of Captain André Botella and two companies of the 5th Vietnamese. Finally, 1,000 yards south of E4 lay the vital strongpoint Eliane 2 (later referred to by Viet Minh survivors as “the fifth hill”), which rose 130 feet above the valley floor. Major Jean Nicolas had his headquarters and two rifle companies of the 4th Moroccan Rifles dug in on Eliane 2, and had constructed a strong summit position consisting on bunkers, fortified trenches, and parapets.

Two salient terrain features lay close to Eliane 2 that would present grave problems for the defenders—two outlying hills of the same elevation, dubbed Baldy and Phoney, which had not been brought into the French defensive perimeter due to lack of men and materiel. Eliane 2’s lower eastern slope led directly to Baldy, while Phoney lay just to the northeast. De Castries had been assured by his artillery officers that these two outlying hills could be kept free of enemy activity by artillery fire alone—a grave miscalculation, as it turned out. The two hills hid much of the Viet Minh activity in this sector. Eliane 2’s lower eastern slope, nicknamed the Champs-Elysées, offered a straight, broad path directly to the strongpoint’s crest and was vulnerable to attack from the wooded gullies surrounding Baldy. Langlais, for his part, was not convinced that the single company of Moroccan riflemen posted in the relatively weak entrenchments on the lower slope could hold out, and he ordered them replaced by a company of paratroopers of the elite 1st Foreign Legion Parachute Battalion.

A number of smaller, more lightly defended outposts (Eliane numbered 12 hills in all) were situated in the flatlands between the eastern hills and the river. Among these were the so-called “low Elianes,” 3, 10, 11, and 12. Eliane 10, west of E4 and E1, was manned by one of the reserve units, a company from the 8th Shock Battalion. Near the Bailey bridge, one of two short spans connecting the eastern hills with the central camp, was Eliane 12, occupied by remnants of the disgraced 2nd T’ai Battalion, which had deserted the strategic strongpoint Anne-Marie, the third and last of the northern defensive outworks to fall, just days into the siege. Many had fled into the hills, while others were relegated to work as porters or became “internal deserters”—men too demoralized or shellshocked to properly function. The better part of Bigeard’s 6th Colonel Parachute Battalion was held in reserve in a bivouac area in the flatlands between the eastern hills and the river near Eliane 12. A second new outpost, Junon, was established at the southern end of the central camp to back up the Elianes; it housed a force of 1st Foreign Legion Battalion paratroopers, T’ai partisans, French Air Force personnel, and two more of the fearsome quad-.50s.

The People’s Army assault units left their staging areas east of the hill strongpoints at about noon on March 30 and moved forward under continuing rain. At 5 pm that afternoon, Giap’s 105mm howitzers and 120mm heavy mortars opened fire in earnest, and the maelstrom of the Five Hills Battle began. Every GONO position came under heavy punishment; the Five Hills and strongpoint Claudine in the central camp, where the bulk of the garrison’s artillery was housed, were especially hard hit. Shells began falling on Dominique 1 at the worst possible moment, just as the Algerian 13th Company was relinquishing its positions to the 4th Company, 5th Vietnamese Parachute Battalion. The Tirailleurs, as they were known, had just dismounted their heavy weapons and were exiting their trenches when deafening explosions began to rock the hillsides. On both of the Dominique hills, the Communist preparatory barrage ended sooner than usual; it had lasted less than 90 minutes. In the confusion on D1, about 30 riflemen of the 3rd Algerian returned to their trenches to fight alongside the Vietnamese and Legion mortarmen, but the majority jostled their replacements aside in their unseemly haste to get off the hill.

On both hilltop redoubts, the first Viet Minh assault units seemed to spring up from nowhere, leaping from trenches that had been pushed up almost to the barbed wire barriers. French artillery shots fell harmlessly behind the advancing columns. The forward artillery observers on both hills had been seriously wounded, leaving the central camp’s batteries without fire correction orders. The mixed garrison on D1, less than 200 strong, was vastly outnumbered when the full weight of Viet Minh Infantry Regiment 209 fell like a sledgehammer blow on the battered, muddy outpost. The defenders managed to hold back the attacking columns for almost three hours before finally succumbing at about 9:50 pm. No such stout resistance was offered a short distance to the southeast, where the panicky Algerians on Dominique 2 collapsed almost immediately. There was still daylight left at 7 pm when Bigeard, in his command post on Eliane 4, radioed Langlais that he could see large groups of Algerians streaming down the reverse slope of D2 in the direction of the river. Other defenders on D2 simply remained in their trenches and discarded their weapons, waiting with their hands on their heads to be taken prisoner. Dominique 2 was lost just after 8 pm.

On Eliane 1, the Moroccans watched the sudden fall of D2, and after the heavy pounding they had absorbed in the opening barrage were drained of any will to fight. It was 7 pm when Captain Botella, also on Eliane 4, reported seeing swarms of Moroccan infantrymen falling back from E1 past his own position. The garrison on E1 was overrun by the enemy’s Infantry Regiment 174 in a little under an hour. GONO reported the loss of Eliane 1 at 7:30 pm. Fortunately for the GONO garrison, the defenders on Eliane 4 proved to be made of more sturdy material than their comrades on E1. Botella’s Vietnamese paratroopers had also been punished by the opening round of shelling, then attacked in waves by Regiment 174, their heavy weapons platoon wiped out and several officers and NCOs killed or wounded. Still, after witnessing other units to their front and on their left flank collapse, and with a vicious pitched battle breaking out in the semidarkness on E2 on their right flank, the redoubtable Vietnamese on Eliane 4 fought bravely all night and successfully held their position against overwhelming odds.

Although they had failed to breach the perimeter on Eliane 4, the Viet Minh attackers, after overrunning three of the five hill redoubts, were in position to inflict further losses upon the camp’s weakened eastern defenses and possibly achieve a breakthrough to the central camp. The assault on Eliane 2 had only begun; the Communists enjoyed a huge advantage in numbers, at least five-to-one, and still had one entire regiment in reserve with which to exploit their earlier successes. On Dominique 3, the West African gunners and Algerian Tirailleurs sensed an attack was imminent. In the last rays of sunlight, they were stunned to see broken companies of Algerians retreating down the slopes of D2 about 1,000 yards to their front. Brunbrouck reported the retreat but couldn’t convince his superior officers back at the battalion HQ that both hilltop Dominiques had indeed been overrun.

Dominique 3 was bracketed by the southward sweep of RP41 to the east and a dead arm of the Nam Youm to its rear; an old north-south drainage ditch, six feet wide and deep, provided a sunken lane down the center of the battery’s position. Command posts, shelters, and ammunition dumps were dug into both banks of the ditch. Four sandbagged gun pits led off from D3’s eastern edge; the ditch was sealed off to the north by barbed wire entanglements sown with mines. Another barbed wire barrier and minefield led out to the east, to protect the battery’s front. The Algerian riflemen were dug in from north to south around the gun pits.

As they neared D3, most of the fleeing Algerians veered off to the south, heading for the two bridges that led back to the safety of the central camp. A few small groups, including a handful of the 5th Vietnamese Parachute Battalion, survivors from D1, sought refuge inside Brunbrouck’s perimeter. The victorious, green-clad Viet Minh columns, advancing from due east, were surprised by machine-gun fire from D3 and halted temporarily. After the last of the refugees cleared his front, Brunbrouck ordered his Tirailleurs to open fire as well. Some of the West African crewmen had infantry weapons, and a French officer incorporated those who could be spared into the defensive front alongside the Algerians. But the night and the weight of overwhelming numbers were on the side of the Viet Minh—it was only a matter of time before they came on again.

Brunbrouck, an experienced and resourceful young officer and a veteran of Na San, had by now managed to convince his battalion HQ of the direness of the situation and passed on new target coordinates to the 4th Artillery Regiment’s command post. Soon, the battery’s two sister batteries on the west bank of the river were firing in her support. Before the Communist columns charged the battery’s perimeter again, Brunbrouck ordered his gun crews to lower the barrels of their howitzers to zero elevation and set the fuses to minimum delay; when the attack came, the weapons would be firing horizontally, point-blank, at the massed enemy formations. The high-explosive shells would detonate just instants after exiting the muzzles of the big guns.

When the Communist onslaught by Regiment 141 began, the leading columns were met by machine-gun and small arms fire from D3’s front, supporting artillery from the central camp, and ruinous, prolonged bursts of fire from the quad-.50s on Epervier, in addition to the terrible gauntlet of round after round of high-explosive shells from four 105mm howitzers bursting in their midst. Soon, huge, bloody gaps were being torn in the closely packed columns of Viet Minh attackers. In the garish, dim glare of parachute flares, the carnage was beyond belief. Heaps of slain attackers began to appear along the barbed wire barrier; dozens of broken, bloody Viet Minh corpses festooned the wire itself. Against such a murderous fusillade, Regiment 141’s columns wavered and began to fall back. The defenders on D3 enjoyed a short respite, but the human-wave attacks were far from over.

Brunbrouck took advantage of the lull to visit his gun crews, encouraging the exhausted men of his battery and their Algerian defenders. At around 2 am, renewed human-wave assaults began once more. A fresh unit, the 54th Battalion of Viet Minh Regiment 102, until now held in reserve, looped around the long southern flank of D2 and attacked Brunbrouck’s perimeter from the southeast. As columns of fresh troops pressed up to the wire, moving over and around the bodies of those who had gone before, Brunbrouck’s howitzers, now red hot to the touch, again opened fire, alternating between impact and minimum-delay fuses to shred both the enemy’s front ranks and the columns coming up behind them.

Again, the People’s Army attackers halted, but only temporarily; Major Knecht, at battalion headquarters, worried that Brunbrouck’s tired garrison of 180-odd men might not be able to hold against further attacks, and requested infantry reinforcements from Langlais. With simultaneous battles raging on the Elianes and on Huguette 7, Langlais had no troops to spare and had to refuse. Langlais spoke directly with Brunbrouck over the radio, instructing him to sabotage his weapons and fall back if the situation became impossible. The 4th Battery’s gunners continued their killing fire; an attempt by the Viet Minh to outflank Brunbrouck’s position from the north was halted by the fire of the quad-.50s on Epervier. Another group of attackers attempted to break through and reach the drainage ditch, but was stopped by the heavy machine gun that covered the battery’s northern perimeter.

Brunbrouck was told a second time that he could spike his guns and pull back his garrison if he deemed it necessary. Again he refused. A force of Communist infantrymen looking for cover in a sunken lane near the perimeter’s northern edge was wiped out to the last man by command-detonated charges buried there several days earlier on Langlais’s instructions; the next morning, at least 200 dead enemy soldiers were counted at that spot. Finally, the People’s Army attacks lost momentum, and before dawn the survivors of the 54th Battalion fell back. There would be no breakthrough this night, at least not on the northeastern front. Two regiments from Giap’s most experienced division had failed to get past the guns on D3. The crews there had fired an incredible total of almost 1,800 shells, an amazing feat under the best of conditions. Given the atrocious casualties his men inflicted on the enemy, Brunbrouck’s losses were surprisingly light—none killed, three wounded, and a handful of burn cases.

Over on Eliane 2, staunch French resistance had kept the Viet Minh from digging trenches up to the perimeter. To advance on E2, the People’s Army first had to move up and secure Baldy hill. This was accomplished by Regiment 98 in about an hour while the garrison on E2 was being pounded by the artillery barrage beginning at 5:30 pm. Prior to their attack upon Champs-Elysées, the Communists raked its trenches unmercifully with recoilless rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire from Phoney hill, inflicting heavy casualties on the Legion paratroopers there. Despite that punishment, however, the first Viet Minh attack turned into a disaster. At 7 pm, two separate battalions of Viet Minh soldiers marched up a dry streambed and approached Eliane 2 bunched too closely together, breaking a cardinal rule of infantry tactics. The two columns attempted to breach the barbed wire just 100 yards apart and were butchered by artillery fire coming from strongpoint Isabelle. The 105mm guns on the southern satellite were firing airbursts, particularly lethal against massed concentrations of infantry.

Although the first thrust upon his position had been halted, Major Nicolas was aware that the 1st BEP paratroopers in the lower trenches had suffered heavy losses, and a little after 9 pm he ordered their company commander, Lieutenant Jean Lucciani, to pull his troops back up the hill to join the 4th Moroccans in stronger positions near the summit CP. Shortly after 10 pm, after occupying the battered trenches at the foot of Champs-Elysées, the troops of Viet Minh Regiment 98 rose and charged up the slope of Eliane 2 in waves. In minutes, the fighting escalated into furious hand-to-hand combat, and the outnumbered Moroccans and legionnaires were forced to fall back toward the crest of the hill.

Langlais lost communication with Nicolas, whose obsolete radio malfunctioned when he attempted to report the renewed assault. Langlais, assuming E2’s summit had been overrun, called down an artillery strike on it. Bigeard, monitoring the battle from his post on E4, saw that the garrison on E2 had contained the immediate threat and countermanded the fire order. He also dispatched one of his own companies of paratroopers to aid the defenders on E2; they arrived at the vital outpost at about 1 am. As the night wore on and the fighting continued, Langlais cobbled together five successive counterattacks to support the outnumbered defenders on Eliane 2. Two U.S.-made tanks crossed the Bailey bridge to join the battle, and by about 3 am, Regiment 98 had been fought to a standstill. At 4:30 am, the surviving attackers began falling back. A fresh Communist battalion had been brought up to occupy Champs-Elysées, but after the final GONO counterattack just before dawn, the new unit held only a small toehold on the edge of E2’s eastern slope.

When the sun finally rose, the surviving Moroccan riflemen and Colonial and Legion paratroopers, spent from their ordeal and suffering heavy casualties, gathered near the parapets overlooking Champs-Elysées and gazed down the hillside to find the slope totally blanketed with dead and wounded. Patrols moving cautiously down the hill counted 1,500 Viet Minh and 300 CEFEO dead. On the northwest front, strongpoint Huguette 7 had been shelled heavily and then attacked by a veteran regiment from the 308th Division. After suffering the loss of several trenches early in the fighting and being refused reinforcements by Langlais, who had his hands full on the eastern front, the outnumbered company of Vietnamese paras of the 5th Vietnamese Battalion, under the command of Captain Alain Bizard, rallied and retook all lost ground. By dawn on March 31, Huguette 7 was secure.

The first night of the Five Hills Battle was over. Although intact, the French fortifications were heavily damaged and Giap’s forces had, at heavy cost, captured three of the five hills. The battle on the eastern front now degenerated into an ugly war of attrition that dragged on unabated, day and night, until the morning of April 4, when the Viet Minh began pulling back from Eliane 2. The Communist battalions seized territory during the night, only to have the French counterattack at dawn. With every piece of new ground his soldiers secured, Giap moved his big guns closer to the French perimeter, which shrank every time a redoubt was lost due to the cumulative effects of constant shelling, human-wave attacks, trench warfare, and heavy monsoon rains.

The appalling losses his army suffered in the Five Hills fighting precipitated a serious crisis in morale in the Viet Minh ranks, and Giap was forced to revert to the nibbling-away tactics of siege warfare while he waited for reinforcements and supplies to arrive at the front. As April dragged on into May, and negotiations in Geneva, Switzerland, got under way, the exhausted GONO garrison trapped inside the sweltering “chamber pot” no longer fought to win, but only to hold out for as long as possible, believing someone would come to their rescue. Lt. Gen. Navarre, who had ordered the reoccupation of Dien Bien Phu in the first place, still held out hope that a cease-fire agreement could be negotiated before the fortress was overrun. The fate of the beleaguered garrison was the focus of worldwide attention.

Because the camp’s airstrip had been closed in late March due to unexpectedly heavy and accurate shelling, several thousand seriously wounded CEFEO soldiers were now lying, stranded and in desperate need of evacuation, in dank underground hospitals where French surgical teams worked feverishly in knee-deep mud and filth. The garrison’s numbers had been reduced by the loss of hundreds, if not thousands, of troops to “internal desertion.” More and more supply loads being parachuted into the basin were misdropped into enemy territory; and large areas of the defensive works were either underwater or had become waist-deep sewers. The garrison’s last faint hopes for rescue—overland relief by a column of Laotian and French troops on the march from Laos and a proposed operation of massive bombing raids against Communist troop concentrations and supply lines by American aircraft—proved illusory.

General Giap was nearing the pinnacle of his career. He had succeeded in harnessing that particularly Asian strength—the weight of massive, overwhelming numbers. Now, after transforming his guerrilla forces, with massive Communist Chinese and Soviet bloc assistance, into a modern, conventional army, he was poised to bring an end to French hegemony in Indochina and continue the Viet Minh struggle to bring all of Vietnam under Communist rule. When the guns finally fell silent in the Dien Bien Phu valley early on the morning of May 8, the war, which had lasted almost eight years, was over. But in the ensuing weeks, at the negotiating tables in Geneva, the groundwork was laid for decades of further bloodshed and strife. Tens of thousands of young American soldiers would find themselves fighting and dying in place of the long-departed French, whose dreams of colonial glory foundered and sank in the self-made morass at Dien Bien Phu.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments