By Ronald Anderson

The 1939 war between Finland and Soviet Russia has been a minor inclusion in most histories of World War II. In terms of human resolution and fortitude, though, few battles in military history can compete with the dogged determination of a tiny country of 4 million going head-to-head with a giant neighbor with 150 million citizens.

If the orders of battle for both countries in the Winter War of 1939-1940 were analyzed prior to the onset of hostilities, the analysts would have most likely told Finland, “You don’t stand a chance!” Everyone would have judged such a contest to be a lost cause that should be avoided through capitulation. Everyone but the Finns, that is.

In the end, the desire to remain a free and independent nation drove Finland to mount a successful resistance against a vastly superior foe. The Russo-Finnish War, or “Winter War,” provides stories of savage battles fought with great heroism, stories of Finnish ski troops, acts of bravery in unfathomable weather conditions, and the never-say-die attitude that will inspire generations to come, the world over.

Finland had only gained her independence from Russia in 1917-1920 resulting from developments in World War I. She lived a shaky existence as a free nation until 1939 when the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact was signed by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia—a non-aggression pact. As a part of that agreement, Russia was “assigned” the Baltic States and Finland as part of its territory. Then in October 1939, Russia demanded the right to establish military bases in the Baltic States and in Finland, with additional demands for Finland to revise her borders giving Russia a buffer zone to protect Leningrad from Finnish invasion. Long-term leases on Finnish land were also demanded. The Baltic States had little choice but to agree to Stalin’s demands. Finland refused.

Russia’s eventual decision to take what the Soviet government wanted became a sobering experience for the Red Army. Russian military commanders expected a quick and decisive victory over the Finns but soon found themselves caught in a frozen slaughterhouse. The international press reported that no other battles in its history had ever degraded the Russian Army so badly in the eyes of the world.

In every armed human conflict there are countless acts of selfless bravery and dedication to a cause. The Winter War is no exception. Among many compelling accounts that have emerged from that war the story of one individual stands out.

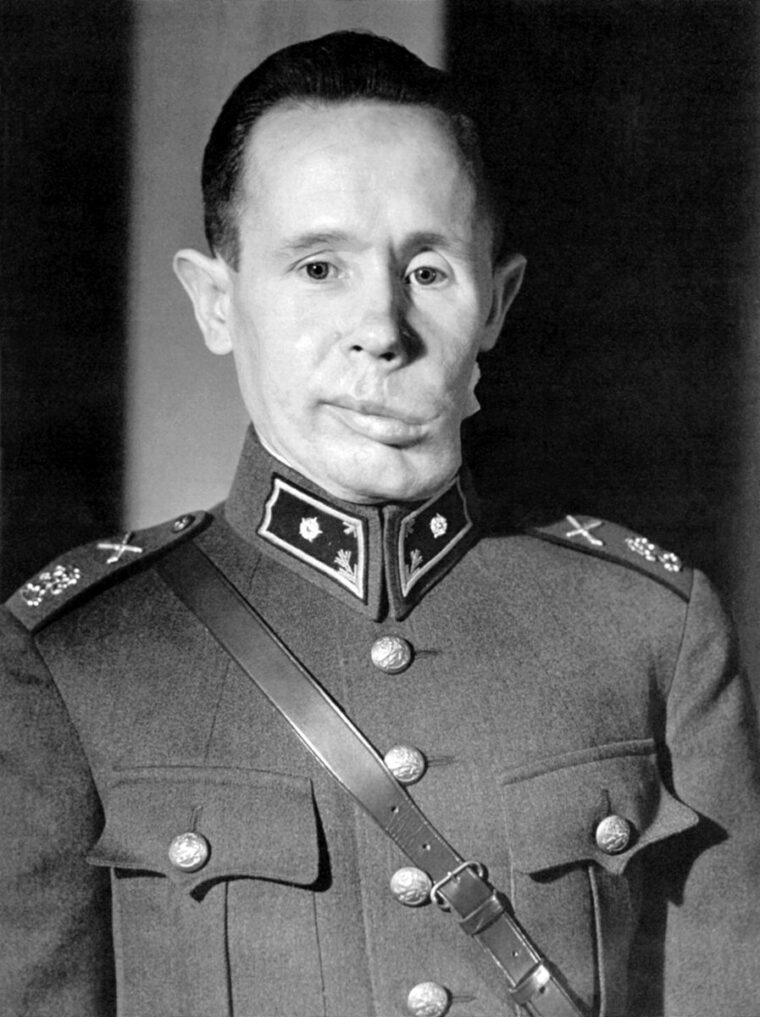

The diminutive Häyhä (5’3”) became a near mythological figure, the absolute embodiment of the Finnish will to fight and survive as a free nation. He fought a “lone war,” not as a participant in mass attacks or defensive actions, but rather as an unsurpassed specialist in his chosen field. He was a sniper that became known to the Soviet Red Army as Belaya Smert, the “White Death.” It has been suggested that, according to information from Russian prisoners at the time, that the severe frost was the real “White Death.” Häyhä was the subject of much Finnish propaganda during a conflict characterized as “David vs. Goliath.”

Few are as feared and hated as much as the members of any fighting force who, through their superior marksman’s skills, have been trained and designated to be a battlefield sniper. A single sniper has been known to keep large numbers of enemy combatants pinned down for long periods of time, everyone being afraid to move into an open position and run the risk of becoming a target for the enemy sharpshooter. Considered “despicable,” captured snipers throughout history have often been summarily executed.

Sniping is a very personal way to wage war. Whereas many soldiers employ a spray-and-pray fire discipline in battle, the sniper actually looks every victim in the face—an intimacy that may cause haunting memories for life.

There have been many noted snipers—Chris Kyle, a U.S. Navy SEAL, had 160 confirmed kills during four tours in the Iraq War; Carlos Hathcock, a U.S. Marine Corps sniper in Vietnam had 93 confirmed kills; Soviet sniper Vasily Zaitsev was credited with 265 kills in World War II (225 during the Battle of Stalingrad). The most successful woman sniper in history was the Red Army’s Lyudmyla Pavlychenko, who had a total of 309 confirmed kills during the sieges of Odessa and Sevastopol. It’s worth noting that the total could have been much higher, as a third-party witness was needed for confirmation.

But the sniper credited with the largest number of enemy kills is not nearly as well known in the U.S. He was a Finnish farm boy fighting in the 1939 Winter War between Finland and Russia whose official kill total could be as high as 542. That’s the number provided by Finnish Army major and sniper instructor Tapio Saarelainen in his book, The White Sniper: Simo Häyhä. Saarelainen interviewed Simo dozens of times between 1997 and 2002. Häyhä never discussed it, but in a memoir found in 2017 put his “sin list” at about 500. Häyhä’s division commander reported the total as 219. A military chaplain recorded the number 259 in his diary. Other sources have used the number 505.

Häyhä was born in 1905 in southern Finland near the Russian border. He was the seventh of eight children born into a Finnish farm family. After his daily work was done, he gravitated toward hunting, shooting, skiing, and pesäpallo, a Finnish form of baseball. He also spent many fond hours trekking through the dense forests that are abundant in his Nordic country. He led the basic no-frills life that was so characteristic of many of his countrymen in that era.

At 17, Häyhä joined the Suojeluskunta (local civil guard) where he was quickly recognized for his prowess with a rifle. He won many shooting competitions, filling a room with trophies. Shooting a bolt-action rifle, he was able to hit a small target 6 times in a row from 150 meters within a minute.

In 1925, at the age of 19, Häyhä began his 15-month mandatory military service as part of a bicycle battalion. Judged to be non-commissioned officer material, he was sent to the national NCO training academy. He made corporal and qualified for formal sniper training in 1927 at the military’s Utti training center. His training officers recorded that he exhibited an uncanny ability to judge the distances of remote objects with extreme accuracy, which served him well in the Winter War. When Häyhä joined the Finnish forces in the 1939 war, he mustered in demanding that he be allowed to keep and use his old training school rifle. Fortunately, that demand was accepted.

The shoulder arm that Häyhä carried into battle was a SAKO M/28-30, serial number 35281. This was a Finnish-made version of the Russian Mosin-Nagant in 7.62x53R caliber, a much better version than the Russian standard. He preferred open iron sights, even for long distances. He would have to raise his head higher to use a scope and sun reflected off the lens could reveal his position. When Häyhä took part in group operations, he normally carried the rapid firing Suomi KP/-31 submachine gun chambered in 9mm.

Other variables to be considered in that war were weather and temperatures. Much of Finland is above the Arctic Circle and the middle of winter is often bone-crushingly cold—with frozen tree limbs exploding like gunfire echoing through the forests.

A soldier whose job it was to lie for hours in frozen snow drifts had to be well versed in knowing how to keep himself, and especially his trigger finger, from freezing. Finnish snipers dressed in layers of wool and carried sugar cubes in their pockets to help their bodies generate heat. Being used to such conditions in their country, they were much better able to cope than were the Russian troops. Häyhä would routinely put snow in his mouth to keep his exhaled breath from being seen by the enemy.

Häyhä’s confirmed kills were achieved in just 100 days at the front—an average of more than five kills per day. In a land where daylight is at a premium during the winter months, Häyhä had to be efficient while there was light. Though he averages five kills per day, his highest total for a day was 25. Confirming the kills was done through a number of methods, such as taking the sniper’s own report, the statements of others, and counting the dead.

Kills made with a Suomi submachine gun were not counted in the official total. Finnish ski troops used a hit-and-run tactic that involved rapidly skiing through camps where Russian soldiers were relaxing or eating around fires, and spraying them with automatic 9mm SUOMI fire. The highly effective tactic caused hundreds of Russian casualties.

Finding suitable targets was less of a problem than it might have been, as Russian troops wore brown uniforms in a snow-covered landscape. Finnish troops were largely clothed in white camouflage capes. On occasion, Russian troops would be ordered to mount frontal attacks across frozen lakes. These attacks were met with withering, heavy machine-gun fire from the opposite bank. Numerous Finnish machine gunners developed severe mental or emotional problems as a result of cutting down hundreds of young Russians, who were ordered to make such senseless attacks. Questionably, the Russian leadership also sent armored vehicles across frozen lakes, some of which broke through the ice.

Häyhä’s successes were heavily reported by the media in an attempt to further encourage and strengthen the embattled citizens of Finland. As news of his achievements reached the public, they also reached the Russians. The Russian military was having problems with Finnish snipers in general, but bounties had reportedly been set on Häyhä’s head—which only made him more dedicated and more careful. It was also reported that artillery barrages were dropped on specific spots in the hope of killing Häyhä. While this might have been true, it may have been exaggerated by Finnish propaganda.

Häyhä’s deadly career ended abruptly on a fateful day in March 1940, when he was spotted by a Russian soldier who fired an explosive round at him, hitting his jaw on the lower left side. After the skirmish, Finnish soldiers piled up the bodies of their fallen comrades, Häyhä included, for transport to the rear. Fortunately, a soldier saw Häyhä’s leg moving and quickly got him into the hands of the medics.

His left cheek, along with much of his upper jaw, and most of his lower jaw, had been blown away. Combined with the blood loss, it seemed unlikely Häyhä could survive this level of injury and trauma.

But he did survive and his recovery took over 14 painful months during which he endured more than 25 surgeries on his face and head. His wounds left him disfigured for life as can be seen in photos taken of him for years thereafter. He accepted all of this bravely and stoically, as was his nature.

Finland’s Winter War ended in 1940, only to be followed by the Continuation War. Häyhä volunteered to serve again, but his military days were over.

After his full recovery from his wounds, the Finnish government gave Häyhä a small farm, and he returned to the rural life that he knew and loved. He became an avid moose hunter and started a dog-breeding enterprise. His celebrity status never diminished, and he attended many hunting trips as a guest of the president of Finland. But all was not happiness for him. He received hate letters and even death threats from anonymous sources that could have been Finns or families of Russian soldiers killed in the war.

A grateful nation presented Häyhä numerous prestigious awards for his contributions. He was also commissioned a lieutenant by war’s end. His highest award was that of becoming a Knight of the Mannerheim Cross, named for the great Finnish Field Marshal and statesman.

Häyhä is considered by most to be the deadliest military sniper in history. In an interview at his residence not long before he died (at age 96 in 2002), he was asked by journalists and reporters if he had any regrets about what he did in the war.

He replied, in essence, that he had no regrets; he was doing what he was told to do and was helping to defend and save his country’s freedom. Simo Häyhä is a name that will long be remembered in Finland—and in Russia, but for decidedly different reasons.

Author Ronald Anderson is a student and researcher of military history and a resident of Prescott, Arizona.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments