By Robert Barr Smith

The year 1883 was one of horror for the people of northern Africa. Grim tidings made their way down the Nile from the benighted wastes of the Sudan, ghastly tales of rebellion and massacre in the holy name of God. The Egyptian government seemed powerless to stop the bloodshed. Venal and complacent, its officials were largely corrupt and its army vicious and undependable. The Sudan, long tottering on the verge of anarchy, was an arid, graceless place where life was cheap and the government’s control did not extend much beyond rifle range.

The Expected One Versus Raouf Pasha

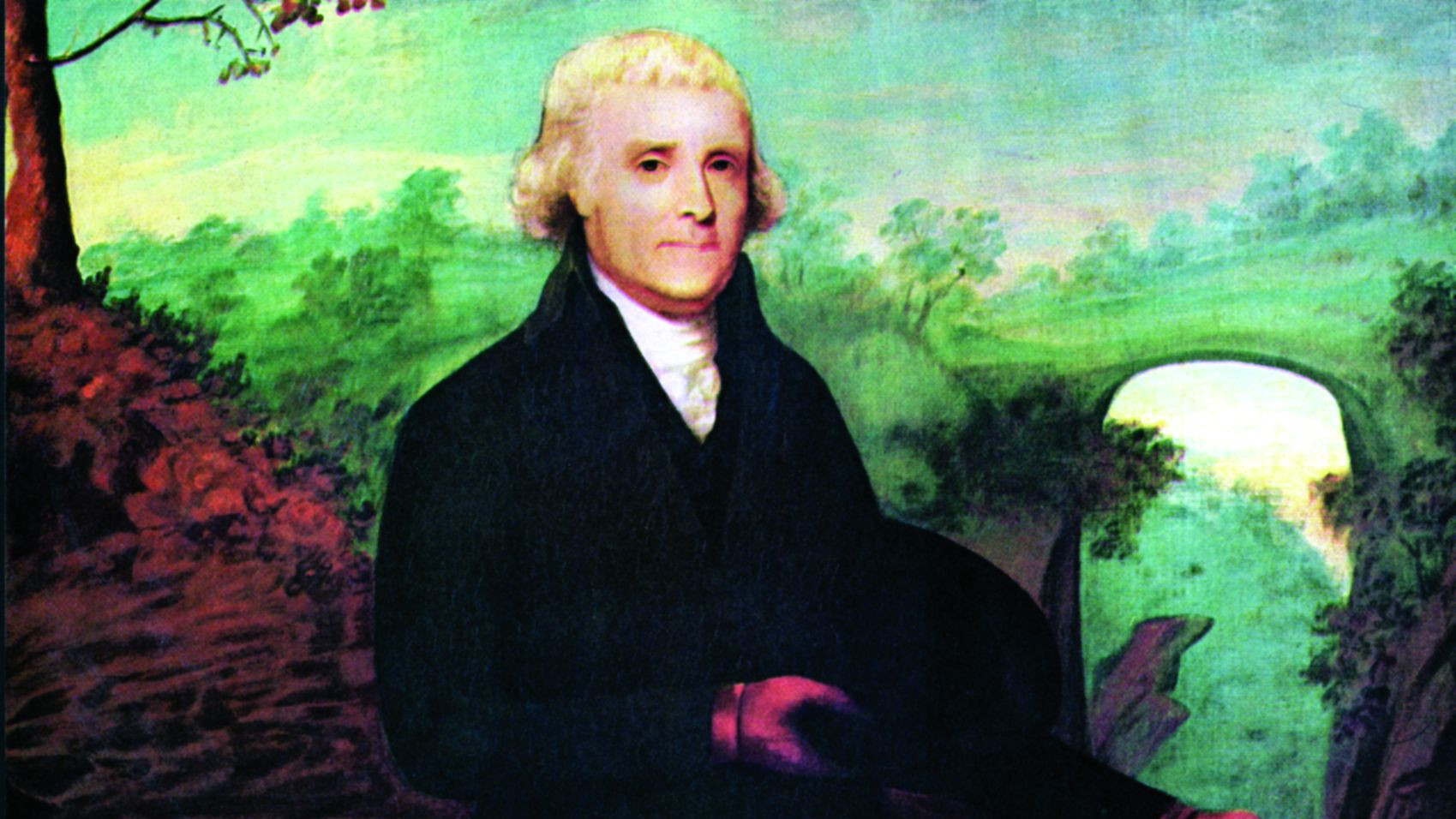

The Sudan’s Muslims believed they had found a savior of their own. His name was Mohammed Ahmed, a 40-year-old apprentice boat-builder and an ascetic Sufi religious leader from Dongola. Given to self-abnegation and visions, Ahmed had proclaimed himself the Mahdi—the Expected One. He had made it his holy mission to expel the hated Turks from the Sudan and carry Islam across the earth, killing all who opposed him. He was welcomed, not only by the ignorant, devout tribesmen, but by others moved by less elevated motives—Arab slavers who had been deprived of their livelihood by the charismatic, enigmatic British soldier Charles George Gordon, better known to history as Chinese Gordon.

Gordon had come to the Sudan in 1874, first as governor of a single province, then as governor of the entire vast region. Armed with little more than his reputation and a profound Christian religious faith, in only five years he had destroyed the roots of the slave trade, freeing miserable columns of chained black prisoners and shooting or hanging slavers. In a single mass hanging, he had executed the son of the Sudan’s leading slaver and 11 of his lieutenants. Now Gordon Pasha was gone from the Sudan, the victim of a political quarrel with Egyptian leaders, and the old corruption and oppression had quickly returned. The whole region was a powder keg, and the self-proclaimed Mahdi became the spark.

The conflagration started in a small way. Gordon’s successor, an inept oaf named Raouf Pasha, made a half-hearted attempt to extinguish the Mahdi. In August 1881, Raouf sent an officer and sometime slaver named Abu Saud to Abba, an island in the White Nile, to capture the upstart messiah. On August 12, two companies went ashore in the hot and humid night—a major mistake, for the darkness deprived them of their only real advantage, their firepower. Abu’s troops blundered carelessly about in the gloom and fell into an ambush. Overrun by a howling mob of Mohammed’s ragged followers armed with spears, clubs, and rocks, the Egyptians fled in panic, leaving six officers and 120 other ranks dead on the island.

The Miserable State of the Egyptian Army

Word of the astonishing Egyptian defeat spread across the Sudan. New recruits for the Mahdi’s cause appeared in the thousands, many of them experienced fighting men from the bands of discontented ex-slavers. In December, the revolt escalated when the Mahdi destroyed a 1,400-man Egyptian force near Fashoda, south of Khartoum on the White Nile. The Mahdi swept into Darfur, west of the great river, and on Sennar, more than 150 miles up the Blue Nile toward Ethiopia. A year after the revolt began, 4,000 Egyptian troops were wiped out in desolate Kordofan, southwest of Khartoum, at the confluence of the White and Blue Niles. The lethal tide of fanaticism was creeping closer and closer to Cairo itself.

In September, the Mahdi led a large army against El Obeid, the principal town of the western Sudan. Repulsed with huge losses by the garrison’s Remingtons, the Mahdi’s people simply starved the town into submission. Hideous scenes of privation followed, with corpses strewn so thickly that carrion birds gorged themselves until they could not fly and were in turn eaten by the besieged. At last, in January 1883, with every sort of animal eaten and children dying of starvation, the city surrendered. In the process, the Mahdi acquired some 6,000 Remington rifles and five excellent Krupp artillery pieces to add to the weapons he had looted from the other Egyptian garrisons.

The Egyptian government heard the desperate calls for help. Some 10,000 men, many of them veterans of the old Egyptian army, were sent south to defend the Sudan. By and large, they were an unwilling, wretched lot, some of whom had to be marched in chains to ensure that they would arrive at all. Two recruits threw lime in their own eyes, hoping to avoid service in the Sudan by blinding themselves. Even those men who might have fought well—in particular the black Sudanese troops—endured such humiliating conditions that their morale was at rock-bottom by the time they arrived. The government attempted to ensure that the demoralized mob was professionally led, hiring Colonel William Hicks, a retired officer of the Indian Army, and making him a lieutenant general.

The Hodgepodge Army of Hicks

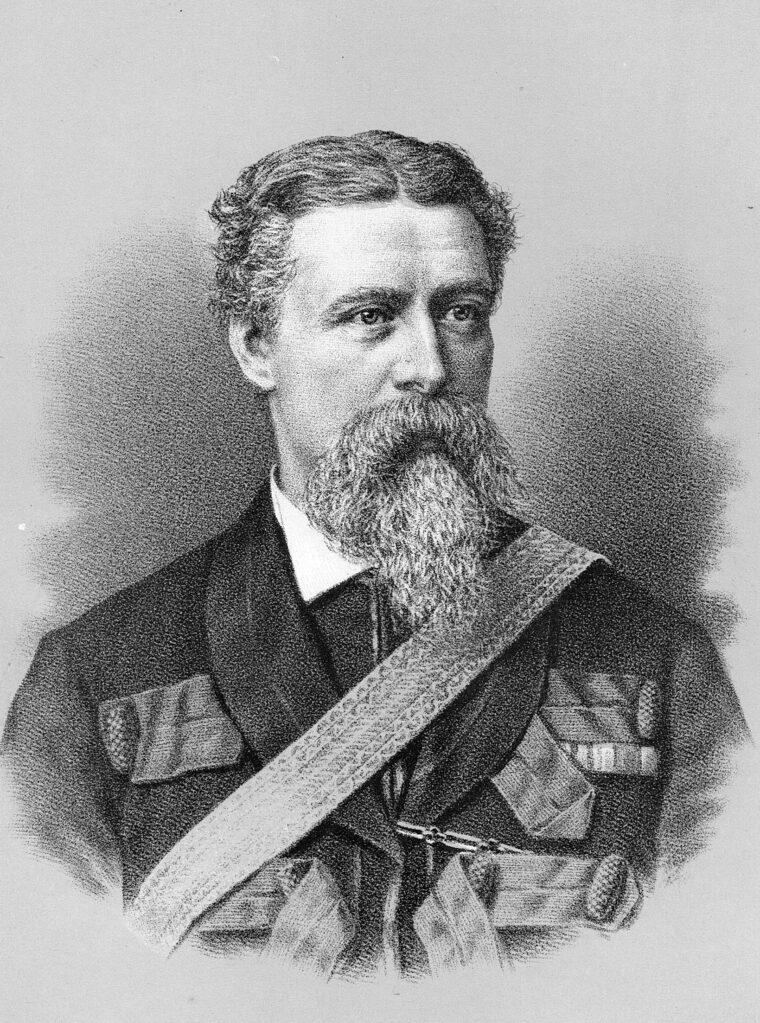

Hicks needed the best officers he could obtain. Colonel Freiherr Götz von Seckendorf was German, and there were two Austrian captains and another officer from the Balkans. Hicks had five British officers, and his chief surgeon, Georghis Dimitrious Douloughlu, was Greek. An able Coldstream Guardsman named Arthur Farquhar was his chief of staff, and Hicks depended heavily on Major Edward Evans, the only one of his cadre who spoke Arabic. He could also rely on a splendid British sergeant-major named Brady, and Hicks was pleased with the performance of an Austrian, an officer named Herlth, whom he assigned to lead the cavalry.

With a few exceptions, Hicks’s Egyptian officers were less promising, and few of them spoke English. Most were not only unreliable and terrified of the Sudan, but indifferent to their leadership responsibilities. “I reduced a Capt. To the rank of Lieut. the other day,” Hicks wrote home, “but it seemed to have no effect for I caught him neglecting his duty next day.” Every day Hicks struggled with endless inefficiency and lack of discipline. “It is no good giving orders,” he reported. “It is no use trying to put things straight. They promise to do what you direct without the slightest intention of acting, and are utterly indifferent, and not in the least ashamed when you find them out.”

Hicks himself was a sapper, an officer of considerable experience, having served 34 years in India, including the desperate days of the Mutiny. He was 53, and if he could not be called a military intellectual, he was a true Victorian fighting officer. He began a rigorous training program, and he and his officers did their best to weld the unpromising mass of reluctant humanity into an army. The first results were not promising. “When the guns were attempted to be brought into action, dire confusion reigned,” Hicks noted. “Men ran against each other; the ground was strewn with cartridges. No one appeared to have the slightest knowledge of how to feed, aim, or discharge the pieces.”

In addition to general apathy and incompetence, Hicks was also plagued by endless disorder among his irregular cavalry, the Bashi-Bazouks, a vicious lot of thieves and killers in the best Turkish tradition. On at least one occasion, Herlth had to draw his pistol to enforce his orders. There were also some curious Sudanese cavalry encased in chain-mail seemingly left over from the Crusades. No matter how hard Hicks’s officers pushed the army, it remained, in the words of correspondent Frank Power of the London Times, “a cowardly, beggarly mob.”

Going on the Offensive

Hicks lacked any reliable intelligence of the Mahdi’s strengths. Nevertheless, he decided on an offensive strategy. He would march west to recover the lost areas of the Sudan, even though he had serious doubts whether his well-armed but spineless force would fight. He was unable to move them except in a monstrous hollow square, a formation that reduced his rate of march to only a few miles a day. To boost the troops’ confidence, they formed three ranks deep, and each man was issued a handful of iron caltrops to throw out in front of him, presumably to puncture the feet of onrushing enemies.

Strangely enough, Hicks’s troops won a surprising victory at Al-Marabi, where several thousand of the Mahdi’s people stormed the unwieldy hollow square. The hail of lead from the square killed several hundred attackers and drove off the rest. It was a good beginning, but the next campaign would be a far more serious proposition—nothing less than a plan to clear the huge province of Kordofan of the Mahdi and his horde. The odds were long, and Hicks knew that his command was still unready. “I shall have over 21,000 men on the two rivers,” he wrote, “and I would give the whole for two Brigades of English, German, or Indian troops.” Correspondent Power sourly noted, “Even the most sanguine look forward to [this march] with the greatest gloom. We have here 9,000 infantry that fifty good men could rout in ten minutes, and 1,000 cavalry that have never learned to ride to beat the 69,000 men of the Mahdi. I pity Hicks. He is an able, good, and energetic man, but he has to do with wretched Egyptians, who take a pleasure in being incompetent, delaying and lying.”

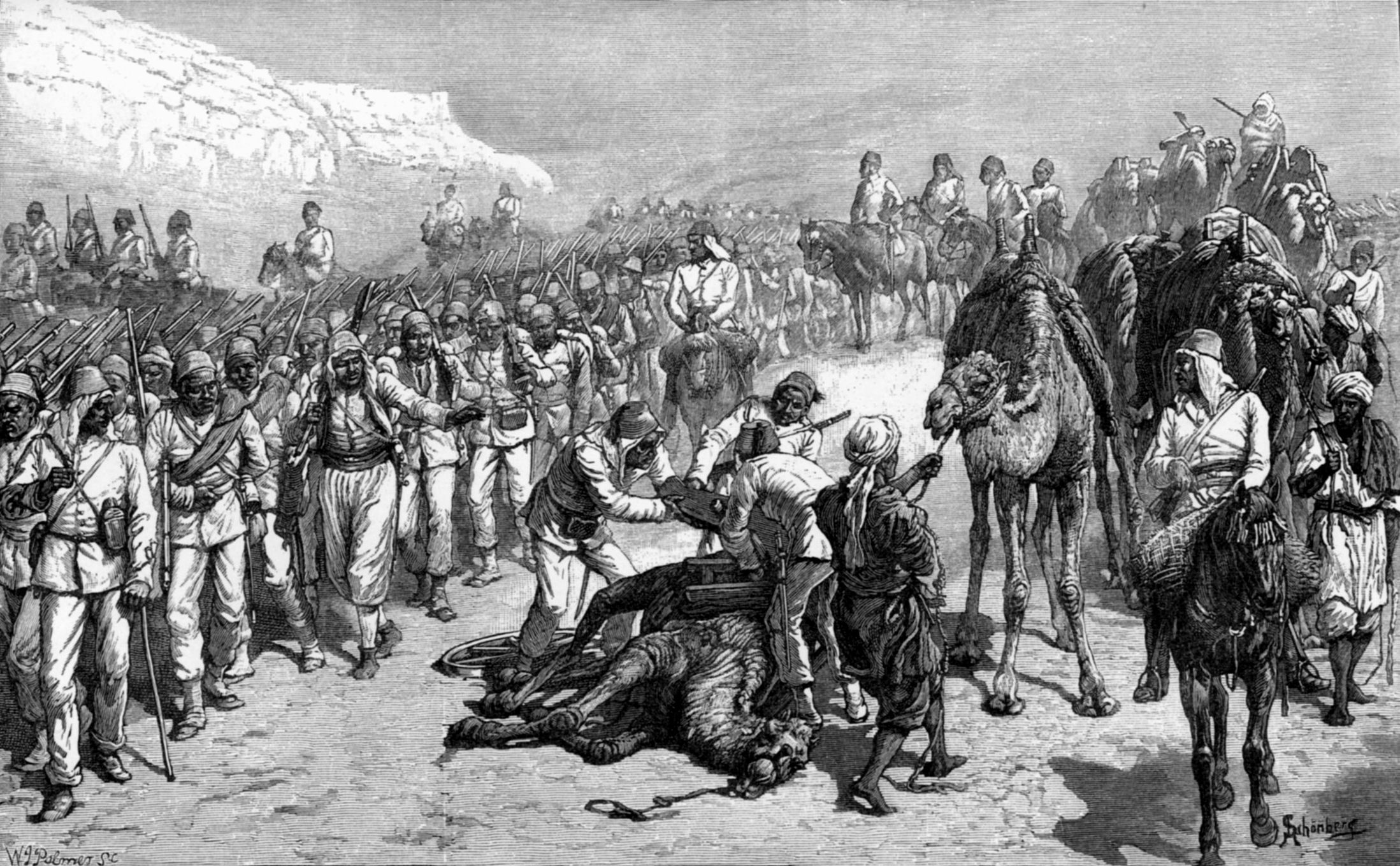

Hicks collected 5,500 camels for transport and turned west into the wastes of Kordofan in September 1883. Along for the ride were correspondents Power, Edmund O’Donovan of the Daily News, artist Frank Vizetelly of the Illustrated London News and The Graphic, and a couple of German orderlies. Also accompanying Hicks was a collection of Egyptian administrators sent to re-establish civil control of El Obeid. Power was lucky; he became sick early in the campaign and returned to Khartoum. The rest, close to 10,000 men and a couple of thousand camp followers, marched west—into limbo.

A Hard March

Hicks’s dispatches to Khartoum bore little good news. He could not bring the Mahdi to bay, for that canny desert warrior simply fell back before Hicks’s plodding advance. Water and reliable intelligence grew scarcer as the army felt its way westward under a terrible sun, in temperatures that reached 127 degrees. The vital camels were ill cared for and died in droves. At Dueim, Hicks decided to abandon his supply line to the Nile, depending entirely on camel-borne supplies. He also elected, apparently on the advice of his officers and the insistence of the new Egyptian governor-general of the Sudan, to forego the direct way to El Obeid in favor of a much longer route. There was a better chance of finding sources of water, but the route was flanked by heavy scrub and swarming with hostile tribesmen. The ponderous squares moved slowly, less than 10 miles a day, consuming precious water at a prodigious rate. Every village was hostile, and many had been burned to deny the army either supply or shelter.

The column began to feel the enemy’s presence. One scout hunting water found a well and started back to report. He realized he had forgotten his rifle—a poignant comment on the military prowess of Hicks’s force—and turned back. The column found him the next day, sitting by the well with both hands cut off. Halfway to El Obeid, the army halted at Akila, which had an excellent water supply. The army rested and drank its fill, but a group of men who wandered away from camp were slaughtered by the enemy. One orderly was found disemboweled.

Worse was soon to come. Hicks discovered that the Egyptians had filled less than a third of the water containers at Akila. Morale plummeted still further as four soldiers and more than a hundred animals died of thirst. After a skirmish with the Mahdi’s followers, Hicks found that the artillery had been so neglected by its commander that it would not fire. There were also disputes over the reliability of the local guides, and further dissension between Egyptian and European officers. Nevertheless, as an admiring foe remembered years afterward, “Hicks was full of courage like an elephant, and he feared nothing.”

The last word from Hicks came in a letter to his wife dated October 4, 1883. “I now hear,” he wrote, “that there is a broad belt of impenetrable jungle along the Khor or water course we are depending upon. If this is true I don’t know what I shall do, for the Army cannot march through it. At present too I know nothing of the water supply whether there is any or not, and with the very existence of the Army, the lives of 10,000 men, dependent upon my decision and no reliable information, the anxiety is very great—almost too much. Fancy marching an Army of this strength through a country where one is entirely dependent upon pools of rain water—10,000 men and 6,000 animals to be supplied daily and no certainty of finding a pool.”

First Day of Battle

The army finally reached Er Rehad, 40 miles from El Obeid, where there was some water. The bedraggled force took a four-day halt and Hicks sent out a fruitless reconnaissance. It was said that the Mahdi had summoned a reinforcement of 40,000 angels to aid the faithful in the final fight. Orderly Gustav Klootz decided he had seen enough and deserted, preferring the chains of the Mahdi’s camp to the fate he foresaw for the army. Klootz would survive years of captivity to tell his tale.

Morale was nonexistent, destroyed by shortage of water, the Mahdi’s propaganda, and the terrible feeling of isolation. Hicks had only one course of action open to him—he had to press on. Along the way, he received a letter from the Mahdi, offering mercy to anybody who would surrender and accept the authority of the Prophet. A follower of the Mahdi recalled Hicks’s defiant response: “I am Hicks: my arm is an arm of iron and my army carries an army in its belly. If the heavens fall, I will hold them up with my bayonets, and if the earth quakes I will hold it fast with my boot.” There would be no surrender.

Moving in three hollow squares, Hicks’s force was only 15 miles from El Obeid. As the army reached a patch of dense scrub, a spot called Shaykan or Sheikan, the Mahdi’s riflemen opened a murderous fire on the Egyptian square. As the front of the square buckled and panic spread, the great mass of the Mahdi’s men struck the flanks. A desperate fight continued throughout the afternoon. By nightfall, Hicks still maintained some sort of perimeter, although bullets thudded into his massed men and animals all through the night. One of the Mahdi’s men remembered that “so fierce was the fire that all the bark was stripped from the trees and they gleamed white as if washed with soap.” Herlth’s diary, later picked up on the field of battle, gives some feeling of the depression that pervaded the army: “These are bad times; we are in a forest, the bullets are flying from all directions, and camels, mules and men keep dropping down. We are all cramped up together, so the bullets cannot fail to strike. We are faint and weary, and have no idea what to do, the bullets are falling thicker.” The entry ended suddenly—Herlth had been killed.

The Last Stand of William Hicks

The next morning, Hicks kicked the remnants of his force into motion. His men were terrified and desperate with thirst, but somehow he got them a mile or so closer to El Obeid. There the fire of the jihadiya and the massive weight of the Mahdi’s torrents of howling spearmen stopped the squares cold and they began to come apart. Thousands of warriors rushed screaming at the collapsing squares, urged on by the Mahdi’s solemn assurance that “all the angels and all the jinns will fight for you. [The Egyptians’] souls are already caught in our hands.”

They were. As one side of a square dissolved, some of the troops on the other faces of the square turned around and opened fire, catching the Mahdi’s people in a crossfire, but also hitting many of their own comrades across the square. The Egyptian defense fell apart amid hideous scenes of panic and slaughter. When the squares broke, many of the Egyptians took to their heels and were cut down as they ran. Some fought to the end, others tried to surrender, and a few survived by hiding under piles of their dead comrades.

One who survived was Hicks’s cook, who was captured and spared, having somehow managed to convince the Mahdi that he was a doctor. He appears to have practiced medicine—God help his patients—with the Mahdi’s forces until he escaped five years after the debacle at Shaykan. But for Hicks and his surviving officers there was no thought of surrender. One survivor told the story much later: “Hicks Pasha and the very few English officers left with him, seeing all hope of restoring order gone, spurred their horses and sprang out of the confused mess of wounded, dead and dying. These officers fired away their revolvers, clearing a space for themselves, till all their ammunition was expended. They killed many. They had got clean outside. They took to their swords and fought till they fell.”

They made their stand together under a large tree and fought to the last,

brave men dying in a dubious cause. Hicks fought on foot with his saber until he fell in a shower of spears. His head and von Seckendorf’s, impaled on spears, were sent in triumph to the Mahdi. Hicks’s courage so impressed the Mahdi that the Englishman was buried with honor, but the rest of the Egyptian dead, something between 8,000 and 10,000, were simply left, stripped of clothing and equipment, for the hyenas and vultures. The few prisoners, naked and roped together, were dragged in triumph into El Obeid, together with the captured guns and the rest of the booty, while the Mahdi’s followers shouted in adulation.

The Mahdi’s Great Victory

For a while, nothing but dreadful rumors reached Khartoum. Then the ghastly news filtered back across the great emptiness west of the Nile. The entire army had simply vanished. Not one man of all those who had marched west returned to tell the tale. The Egyptian government was in panic, Europe was appalled, and many westerners fled Khartoum, hurrying for safety downstream before the Nile was closed to them.

From that time onward, there were few people anywhere in the Sudan who did not believe in the Mahdi’s divinity. Recruits flocked to his standard, and his fanatic followers would carry on his vision for years after his death in 1885. Khartoum would fall to his faithful, and in that doomed city would die Chinese Gordon, sent back into the Sudan too late to save it. The Mahdi’s visionary spirit would hold sway until 1898, when the bubble burst forever before the magazine rifles and Maxim guns of a well-trained Anglo-Egyptian army under Sir Horatio Albert Kitchener, at Omdurman. On that day, Gordon and William Hicks would be avenged.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments