By Robert Barr Smith

The great waves were huge and black, greedy tentacles of the North Sea clawing and snatching at the battered ships struggling in the icy dark. The night was wild as a witches’ Sabbath and cold as death. Through it, storm-battered ships of the Royal Navy and Germany’s Kriegsmarine groped blindly for one another off the coast of Norway.

Both nations knew the value of the little Scandinavian nation. Just two months before, the destroyer HMS Cossack had startled and infuriated Hitler when she bore into a fjord, deep into Norwegian territorial waters, and sent a boarding party over the side of the German supply ship Altmark, milk cow for pocket battleship Graf Spee. In a brief firefight, the Royal Navy boarders killed or subdued Altmark’s crew, then released hundreds of British Merchant Navy sailors taken prisoner by Graf Spee.

Hitler fumed publicly about what he called the perfidious British violation of Norwegian neutrality, conveniently forgetting that Altmark had been carrying both weapons and prisoners, a double violation of that same neutrality. But der Führer had done more than rant; he had also decided to act.

HMS Glowworm Gets Separated From Escort Group

Now it was April 8, 1940. The day before, Hitler had launched Weserübung, the surprise invasion of neutral Norway. The British had reacted hesitantly, unwilling to land troops on Norwegian soil until there was clear evidence the Germans were determined to violate Norwegian neutrality. Most major British units remained well offshore to prevent any German breakout into the Atlantic. The precious convoys bound for Britain were still the Admiralty’s chief concern.

Closer in, small Royal Navy units drove north to mount mine-laying operations off Norwegian ports and to locate the German invasion force. The British destroyers took a terrible pounding in the mountainous seas, and sometime during the terrible night of April 6, 1940, a torpedoman named Rickey was lost overboard from HMS Glowworm.

Glowworm, based at Harwich, was at sea with three other destroyers as escort for the battleship HMS Renown. Glowworm’s skipper signaled Renown and got permission to leave the rest of the force, and so Glowworm turned back into the gloom to look for her lost man. She had no luck in the wild sea and turned to rejoin the battleship, but she had lost all contact with Renown and the rest of her escort.

The weather, already vile, turned even worse, and Glowworm reduced speed to just 10 knots. Her gyro-compass out of commission, she steered by magnetic compass. Then, on the morning of April 7, another sailor went missing. This man was found “tangled in ropes, which were trailing over the side.” He was dying, and as a young stoker on Glowworm commented years afterward, “Well, that was a bad omen indeed. For two consecutive mornings, something nasty had happened and we were all asking what the third morning would bring.”

Glowworm was a Gallant-class destroyer, launched in 1935. She was not a big ship, displacing only 1,345 tons as compared, for example, with the British Tribal-class destroyers at almost 1,900 tons, or the American Gearing-, Sumner-, and Fletcher-class vessels, which all displaced more than 2,000 tons. Glowworm was a prewar ship with a lot of miles behind her, armed with no more than four 4.7-inch guns, some antiaircraft weapons, depth charges, and four torpedo tubes. But she was fast, capable of 36 knots, and like other Royal Navy vessels, she was designed to be a good sea-keeper.

On her pitching bridge this dreary morning stood her captain, Lt. Cmdr. Gerard Broadmead Roope, just 35 years old but a veteran seadog in the best Royal Navy tradition. He was a Regular, an able commander, and his crew liked him; they called him “Ard-over,” after his habit of ordering quick and dramatic alterations in course.

An Unexpected Enounter with Two German Destroyers

Roope knew that German units were at sea, so he and his crew were alert, but they could hardly have been prepared for what they were to encounter as the dreadful night began to fade into a wan, weary morning. For in the faint, dreary corpse-light of dawn, Glowworm ran head-on into two big German fleet destroyers, Paul Jakobi and Bernd von Arnim. The nearest German ship first signaled that she was a Swedish vessel, then opened fire on Glowworm.

On paper, Glowworm was not strong enough to fight on even terms with either one of the big destroyers, both substantially larger than she was, both mounting five 5-inch guns and eight torpedo tubes. Nevertheless, Roope closed with Jakobi, firing rapidly. Even though heavy seas had flooded Glowworm’s gun-director tower, she hit Jakobi at least once. Monstrous seas hammered Glowworm, sweeping two more men overboard and making accurate shooting very difficult. Regardless, the German ships, both crammed with soldiers of the Norwegian invasion force, turned away.

A Confrontation with the Giant Cruiser Hipper

Roope was convinced, as torpedo officer Lieutenant R.A. Ramsay later said, that the enemy was “obviously trying to lead us on to something more powerful.” Still, the Admiralty needed to know what heavy German units were at sea and where they were, so Roope elected to follow the destroyers. Some five miles north-northwest, through the gloom, spray, and mist, Glowworm spotted a huge shape—the heavy cruiser Hipper, with her eight big guns and thick armor.

Normally, Roope simply would have tried to shadow the big German, but these were not normal times. The hideous weather would make it very unlikely that he could maintain contact with his big opponent, so Roope elected to fight.

Hipper was a giant compared to little Glowworm. Although the cruiser’s nominal displacement—to comply with treaty restriction—was 10,000 tons, in fact she displaced almost 14,000. She carried eight 203mm guns, roughly equivalent to 8-inchers, plus a dozen 105mm secondary weapons, 12 torpedo tubes, and a 32 antiaircraft guns of various calibers. She was more than twice as long as Glowworm.

Hipper was bound for Norway as well, and she also had troops on board. She opened fire on the little destroyer and hit her with an 8-inch shell on the first salvo. Aware that his small guns could make little impression on Hipper, Roope elected to try a torpedo attack. Glowworm laid a smokescreen and began to close the range, but she was hit repeatedly, including one shell that wiped out the ship surgeon’s sickbay party.

Still another hit carried away Glowworm’s radio antennas and jammed the ship’s steam siren, which thereafter screamed incessantly throughout the rest of the action. Shrapnel killed Roope’s dog, sitting between his legs on the bridge, but the captain was not touched.

As explosions rocked her again and again, Glowworm’s radio room sent out the vital news: heavy German units, close inshore off Trondheim. Her message got through, and far to the south in London the Admiralty drew the right conclusion. The invasion of Norway was on. So Glowworm had finished her vital work and now it was time for her to die as well as possible.

Attacking to the Last

In two attacks in the wild seas, all 10 of the destroyer’s torpedoes missed. His little ship hit again, a large fire raging in his engine room, it must have been obvious to Roope that the destroyer was finished. But Roope and tiny Glowworm were Royal Navy, a ship and captain in the tradition of Grenville, Nelson, Rodney, Drake, and Jellicoe. They would go down fighting.

Sinking, burning, her fragile hull ripped by 8-inch shells, Glowworm painfully altered course toward Hipper. Roope turned to his helmsman on the battered bridge and calmly said, “Ram her.” Roope’s little ship was still capable of 20 knots and he sent her straight into the side of Hipper. In the violent seas, the German’s helm could not answer quickly enough to avoid Glowworm’s charge.

The collision jammed Glowworm’s prow deep into the cruiser’s starboard flank just behind her anchor, ripping away some 130 feet of her armored side. The big cruiser survived, but she was listing, and more than 500 tons of icy North Sea water soon weighed down her massive hull.

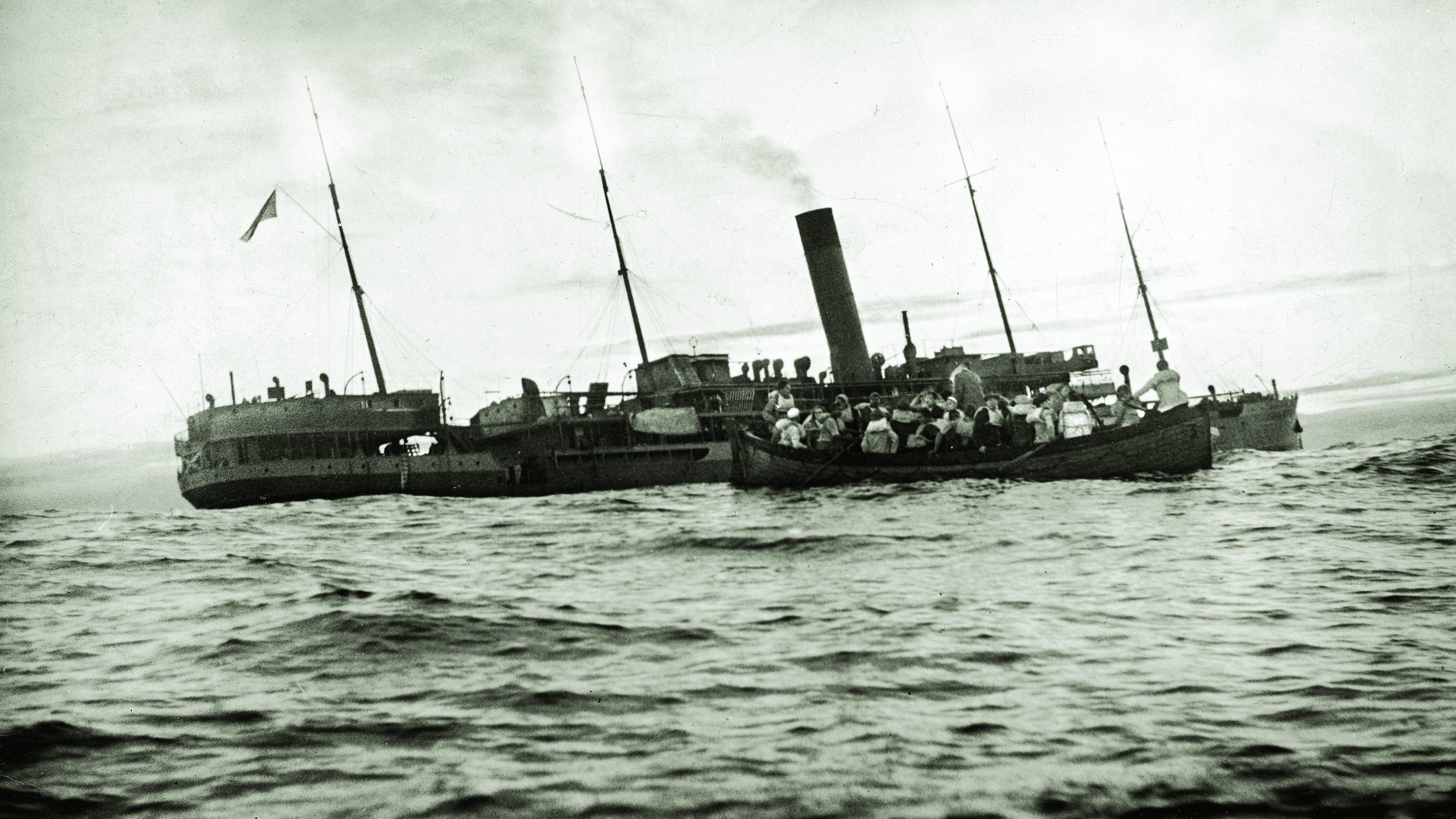

Glowworm drifted away from her wounded enemy, listing badly now, a massive pall of black smoke pouring from her guts. A torrent of German shells hammered the sinking destroyer. Glowworm began to settle by the bow as the fire in her engine room grew increasingly worse. Even with his ship sinking beneath him, Petty Officer W.T.W. Scott, commanding the ship’s last serviceable gun, was still firing, still hitting Hipper. Roope, calmly smoking a cigarette on his bridge, knew that the time had come to save as many of his crew as possible. He gave the order to abandon ship and his crew began to seek the dubious safety of the icy water.

Then little Glowworm exploded and capsized in those wild seas. Those of her 145-man crew not already dead or badly wounded struggled in deadly cold and a foul shroud of fuel oil, trying to stay afloat. Commander Roope, now on his ship’s keel, commented to a petty officer that they would not play cricket yet a while.

Captain Heye Acts Humanely

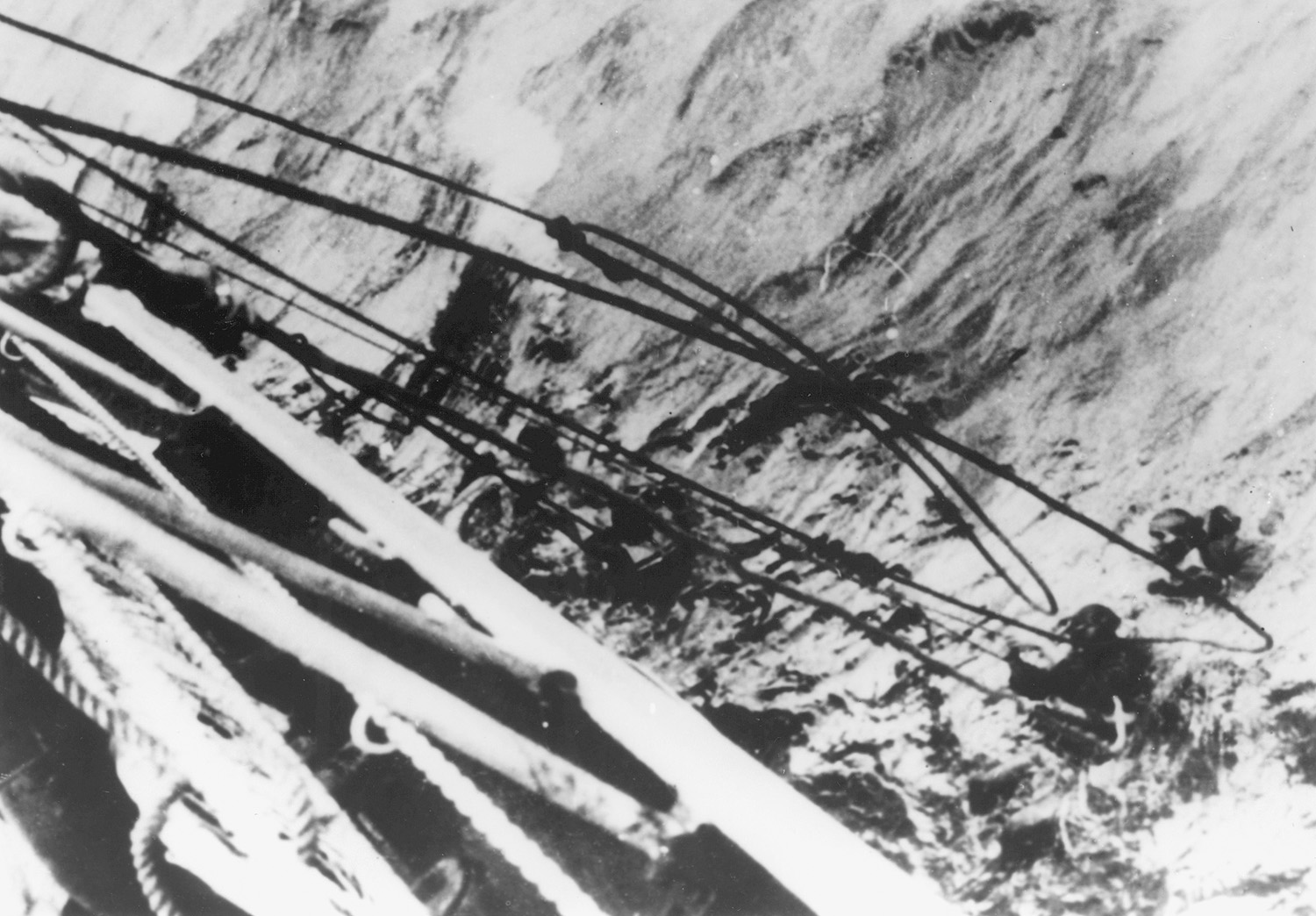

To his everlasting credit, Captain Helmuth Heye of Hipper hove to, put lines over the side, and did everything humanly possible to save as many of Glowworm’s company as he could. He held Hipper downwind of sinking Glowworm to enable the men in the water to get as close as possible to the cruiser, while his sailors and some German soldiers hauled the destroyer’s exhausted men out of the grip of the huge, dark waves. Many of Glowworm’s survivors were simply too far gone from cold to hold on to the oil-slick lines that led to life. These men slipped back into the swells and were gone.

Roope was still alive, close to the cruiser, pulling some of his men to the ropes, helping others get life jackets on in the water. At last he caught a rope himself and was pulled partially up the cruiser’s steel side. Roope might have survived the greedy, greasy swells, but working to save his men he had left it too late to save himself. The huge waves, exhaustion, and the terrible cold had overcome even his enormous courage. Roope lost his hold on the rope and disappeared beneath the waves.

Heye generously held his ship over the site of Glowworm’s death for more than an hour. Thirty-one of Glowworm’s company survived the greedy sea, including just one officer, Lieutenant Robert Ramsay, the torpedo officer. To the credit of the Kriegsmarine, the Germans treated the survivors with great honor, cared for them, wrapped them in blankets, and massaged their freezing limbs. As one sailor recalled, “The next thing I remember I woke up in a bunk in the German sickbay and there were a couple of German sailors rubbing me down with towels getting all the oil off of me. They congratulated us on a good fight.… We must have injured a lot of them in the battle as I looked to another part of the sickbay which was full of German sailors.”

Honors for the Glowworm’s Crew

Captain Heye of Hipper later did a thing almost unprecedented in the annals of war. He gallantly sent to the British Admiralty, through the International Red Cross, a carefully worded message recommending Roope for the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration for valor. In July 1945 the London Gazette, official organ of the government, announced the award of that small bronze cross to Gerard Broadmead Roope.

Lieutenant Ramsay was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and three enlisted men won the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. They included Petty Officer Scott, who so Gallantly served his ship’s last remaining gun as Glowworm sank under his feet. Rescued from the sea, he survived the war as a prisoner. It is pleasant to add that the chivalrous Heye, promoted to admiral, also survived the war, passing away in 1970.

Hipper did not. After the Norway campaign, she sailed twice to raid British Atlantic convoys. Hit and driven away by the heavy cruiser Berwick and two light cruisers on her first sortie, she sank several merchantmen on her second. Then in December 1942, she was beaten off a Norwegian convoy and badly damaged by the superb gunnery of light cruisers Sheffield and Jamaica. She was never fully operational again and was scuttled at Kiel in 1945.

So passed little Glowworm, who did her duty to the end, sent her vital message, did what damage she could in hopeless battle … and died well. But the Royal Navy does not forget signal courage and dedication, and teaches her new sailors about such things. Every new generation of recruits will learn about Glowworm and how she died, and a little of her spirit will live on in them—and that is not a bad legacy.

Robert Barr Smith is a retired U.S. Army colonel and serves as associate dean for academic affairs at the University of Oklahoma Law Center in Norman.

We have a lot of documentation belonging to Able seaman Harold Foot who survived the sinking of the Gloworm, this includes medals, photographs etc, is there anywhere they would he of value

MY GREAT GRANDFATHER Edwin James Kennth Brown was Lead Seaman on the Glowworm.Would you have any pictures of the crew. My mother was only 8 when he passed I would love to surprise her with a picture as she doesn’t have any of him. Thank You Barb

Thank you for sharing the story of this gallant crew and ship. They all did their utmost duty for each other, King and country. Thanks for also sharing the humanity of ADM Heye, a worthy foe. Great sympathy for the families of the lost.