By Duane Schultz

Major Evans Carlson stood on a rickety platform built from wooden crates, the kind their rations came in. He said nothing for a moment as he looked out over the young Marines he and his executive officer had personally selected after grueling interviews. These were the elite, the toughest and most adventurous of the already tough and daring Marines. These were the men of the newly formed 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, America’s first special operations team, trained to strike back at the Japanese in the hit-and-run style of the British commandos.

It was 3 pm on a chilly, rainy day in the second week of February 1942. The Marines were assembled in the middle of a muddy field surrounded by eucalyptus trees, which made the whole camp smell like menthol cough drops. This dismal place was called Jacques Farm, five miles south of Camp Elliott, a rapidly expanding part of the Marine Training Center near San Diego, California.

In the two months since the Pearl Harbor Attack, U.S. forces in the South Pacific were being beaten back in one battle after another; Wake Island, Guam, and Bataan were no longer unknown names. Throughout the nation cries arose for America to strike back against the Japanese.

Carlson’s Raiders, as the media called them, would thrill Americans with the first victory against Japanese-held territory, tiny Makin Island, some 2,000 miles west of Pearl Harbor. Evans Carlson and his men became instant national heroes on a huge scale, celebrities filling the headlines of every newspaper in the country with two Hollywood movies glamorizing their exploits. Everyone knew about Evans Carlson and his Marine Raiders.

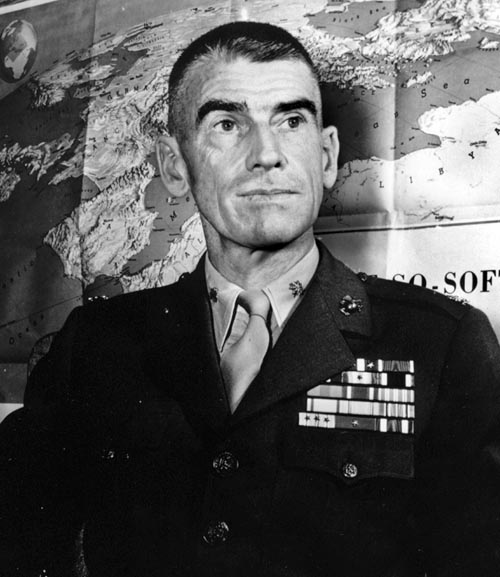

Carlson did not look much like a hero that day at Jacques Farm. He was 46 years old and rail thin; although he stood tall and straight, he appeared frail. He had piercing blue eyes, a long nose, and a pronounced, chiseled jaw. Historian John Wukovits described him as “an intellectual who loved combat; a high school dropout who quoted Emerson; a thin, almost fragile looking man who relished 50-mile hikes; an officer in a military organization who touted equality among officers and enlisted; a kindly individual with the capacity to kill.” The first thing he did at Jacques Farm was take out his harmonica and lead his men in singing the national anthem.

Carlson’s executive officer did not look like a hero either. The 35-year-old captain was also thin, prematurely balding, and seemed in poor health. He had vision problems and flat feet, so he could not wear regulation combat boots. As a child he had suffered from a heart murmur and frequent bouts of pneumonia and was often so weak that his father had to carry him. He was also nervous, socially anxious, and suffered from ulcers. Through sheer force of will, he became a good officer, respected by Carlson and his men. His name was James Roosevelt, and both he and his father, the president, played pivotal roles in bringing about Carlson’s Raiders.

When the last words of the national anthem rang out that day at Jacques Farm, Carlson put away his harmonica and announced that he had a lot to tell the men about their lives as Raiders. They would train and fight like no other outfit had ever done; he was not exaggerating. He talked about his years in China, where he learned from Mao Tse-tung how to fight the Japanese, and about his months with the Chinese Communist Army operating behind Japanese lines. He said that the Raiders would work together—officers and men as one—the way the Chinese Communists did. There would be no distinction by class or rank; every man would eat the same rations, sleep on the ground, and have the same rights and privileges. No one was better than anyone else.

Then Carlson gave them their battle cry: “Gung Ho!” The Chinese phrase meant “work together,” which was how the Raiders would learn to fight.

Six months later, Evans Carlson and his Raiders had become instant celebrities. Anyone in the States who read a newspaper, listened to the radio, or watched a Movietone newsreel knew about them. Banner headlines screamed the story of the small group of Marines, only 221, who went by submarine to attack the Japanese-held island of Makin. Now Americans had a victory to cheer and heroes to praise.

“Marines Wiped out Japanese on Makin Isle in Hot Fighting,” wrote a New York Times reporter. The press reported that the Raiders cleaned out the Japanese troops. Carlson was quoted as saying, “We wanted to take prisoners, but we couldn’t find any. Our casualties were light. We took more than ten for one. The Japs fought with typical Japanese spirit—they fought until they died. It was a sight to see. There were dead all over the place.”

This was just what Americans needed to boost morale on the home front, giving the enemy a taste of its own medicine. It was too early in the war for most people to realize that government sources sometimes distort or conceal the truth or deliberately issue propaganda. The press had little choice but to go along, even when some reporters uncovered the truth. It was not the right time to mention what had gone wrong on Makin, what was covered up, and would not be known for 50 years. In 1942 America needed a victory, and it got one at Makin—or so Americans were told.

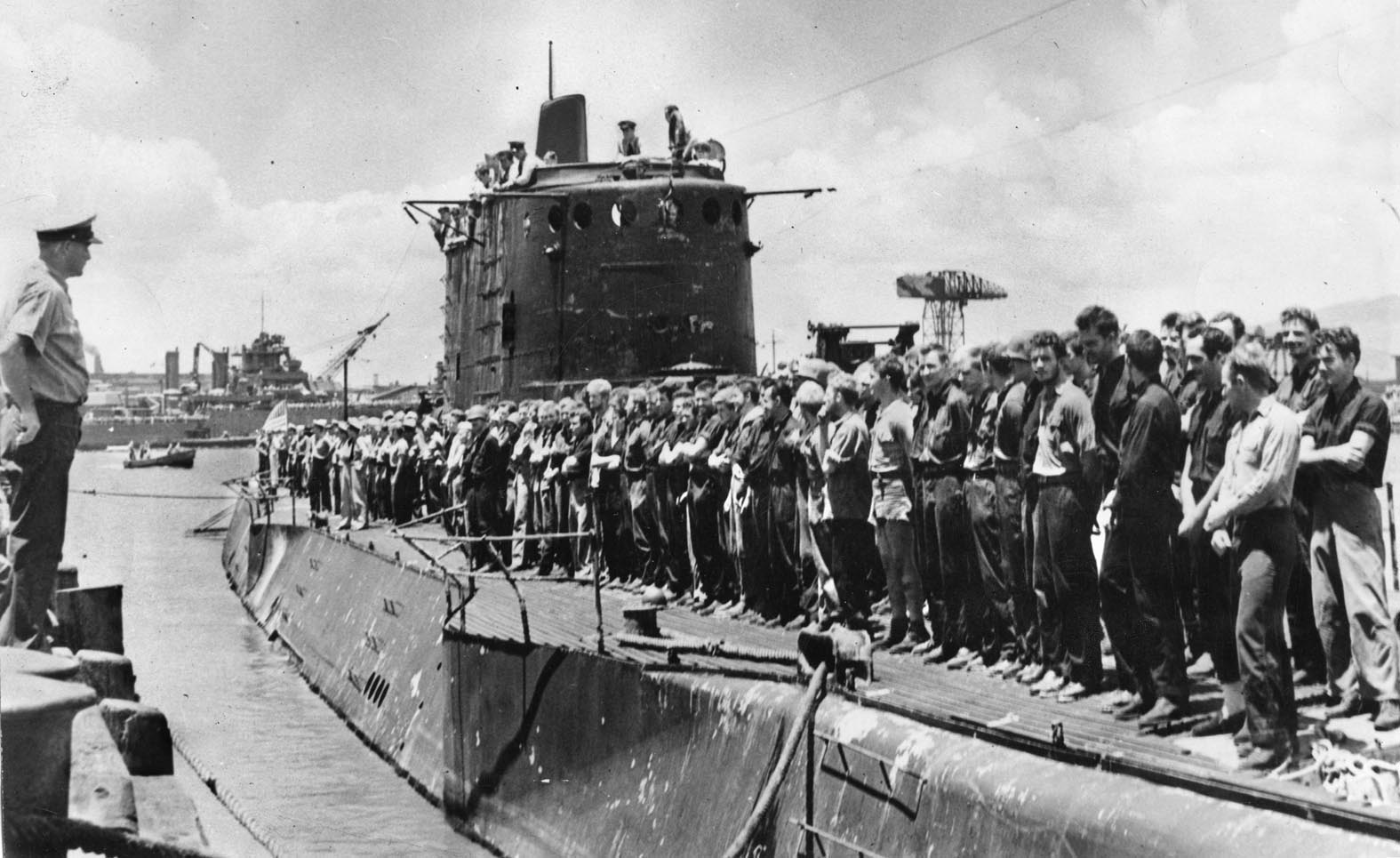

Overnight Carlson and his Raiders had become a sensation. When the first submarine bringing them back from Makin reached Pearl Harbor, James Roosevelt recalled, “We were surprised to find bands playing and the piers lined with cheering people. We had not shaved or bathed or washed our clothes for two weeks, so I sent my men to clean up as best they could. It turned out to be a hero’s welcome.”

Sailors in dress uniforms, standing at attention, lined the decks of every ship the Raiders passed. Bands played the Marines’ Hymn. As the submarine eased up to the dock, a huge cheer rang out. A battalion of Marines in dress blues stood at the ready along with Admiral Raymond Spruance and his boss, Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Behind them waited a crowd of reporters and cameramen.

As Nimitz led a military delegation on board, he stepped up to Carlson, returned his snappy salute, and shook his hand to offer congratulations on a successful mission.

“Makin has made you and your Raiders famous,” he said.

Sergeant Howard E. “Buck” Stidham recalled 50 years later, “The realization was slowly sinking in that we had gone from the status of a courageous and fortunate bunch of dumb-dumbs to what Kipling would probably call ‘a bloody bunch of heroes.’ We had no concept of the hunger the American people had for some good war news and that this operation had attracted the attention of every citizen in the country.”

Three months later, Carlson and his Raiders were back in action, this time on Guadalcanal. They were sent behind Japanese lines where, in what came to be called the Long Patrol, they fought in close combat for 30 days and covered over 120 miles in the steaming jungle. The Raiders killed nearly 500 of the enemy, losing 16 killed and 18 wounded. The press once again lavished praise on “Carlson’s Boys,” the most famous outfit in the Marine Corps, and for a time they were the most glorified group among all of the military services.

Carlson was sent back to the States to be treated for malaria and jaundice. He did not yet know it, but he would never again be allowed to lead men in combat or to serve with his beloved Raiders; the battalion would soon be disbanded. Instead, Carlson was sent to Hollywood to make a war movie.

The script grew out of a two-part article written by one of the Raiders for the Saturday Evening Post.In proper gung ho spirit, Carlson, as technical adviser, insisted that cast and crew bunk together in a nondescript building rather than permitting the movie stars and producers to be housed in a luxury hotel separate from the crew. An article in the 2001 Marine Corps Gazette noted that less than a year after the Makin raid, “Hollywood enshrined Carlson and his Raiders forever with the movie Gung Ho, starring the Southern-drawling Randolph Scott. Followed by Marine Raiders,in 1944, which starred Robert Ryan and Pat O’Brien, these cinematic efforts ensured the Raiders their fair share of glory.”

After his stint in Hollywood, an assignment not of his own choosing, Carlson attempted through all the channels open to him to return to combat, whether in command or not. He would have gone to the front as a private, but even that was no longer an option.

Despite all the public acclaim for Carlson and his Marine Raiders, his career was at a standstill in the middle of a war he had trained for years to fight. It was his very fame, or notoriety, that was holding him back. It had generated resentment, distrust, and jealousy within the top ranks of the command structure, as well as from those of equal rank who were competing with him for advancement. They had never fully trusted him, and his celebrity status had worsened the situation.

Carlson had not pursued a traditional Marine Corps career. He had spent five years in the Army and then joined the Marines only to leave in 1939. He felt compelled to quit, he said, so he could warn the American people about the coming threat from Japan and to criticize the American business community for continuing to sell war supplies to the Japanese. The Marine Corps brass thought that was bad enough, but then there was the matter of the Chinese Communists.

Word spread that Carlson was a Bolshevik, a “Commie” himself. After all, he had been in China in the 1930s, spoke the language fluently, traveled with the Communist army, and met Mao Tse-tung and Chou Enlai. He even wrote a book praising the Chinese Communists. And that motto of his, Gung Ho? That was definitely Chinese. He taught his Raiders that officers and men were equal. That was how the Communist Army operated, so how could Carlson be trusted?

And the Roosevelts! Father and son had become friends with Carlson in the early 1930s when he was in command of the Marine guard at the Little White House at Warm Springs, Georgia. Word leaked that when Carlson went back to China the president asked him to send private reports on what was going on there. Carlson received letters from the White House in return, all without going through proper military channels. For a mere captain to be in private communication with the president was unheard of and strictly against the rules. A growing band of detractors knew that a regulation, orthodox Marine Corps officer would not have done that.

The high command also knew that there would have been no Carlson’s Raiders without the president’s friendship and intervention, and not nearly so much acclaim for the Makin raid had James Roosevelt not been involved. Both situations offered Carlson obvious advantages, but they also served to stoke jealousy among other officers. Carlson did not have to go through channels to obtain whatever supplies and equipment he needed. He only had to tell James, who promptly called his father and arranged everything Carlson wanted. It did not seem that Carlson had to answer to anyone; he operated his irregular outfit according to his own rules.

Then rumors began to circulate after the Makin operation that Carlson had tried to surrender to the Japanese—when he was supposed to be winning and when there were few Japanese troops left alive! Some people claimed there was an actual surrender note, broadcast by Tokyo Rose to American troops in the Pacific Theater.

That there was such a note, written on the second night of the operation when it appeared that some Raiders would be trapped and unable to return to the submarines, seems beyond dispute, but the signature was illegible. The letter was not made public for 50 years. In 1992, Captain Oscar Peatross (then a retired major general) wrote about it in Leatherneck: Magazine of the Marines.He described the incident in greater detail three years later in his book Bless ‘em All: The Raider Marines of World War II.

Carlson made no mention of a surrender attempt in his after-action report on the Makin raid. Admiral Nimitz had given orders that the matter was never to be discussed. Carlson told at least one Raider that Nimitz had told him “that we should rewrite our reports [on the Makin raid] deleting all references to the offer to surrender.” Another Raider reported in 1999 that Carlson had told him that there was a tacit agreement among the few men directly involved “that nothing would be said between us about the surrender note. What’s done is done.”

Other Raiders insisted as recently as 2008 that they never heard anything about a surrender note and that Carlson would never have considered doing such a thing. “There was no way,” one said in 2007, that “Carlson would have surrendered with the President’s son with us. Carlson would have died defending us.”

The origins of a surrender note are lost in a maze of contradictory testimony, claims and counterclaims, assertions and denials, with no resolution in the more than 70 years that have elapsed since the raid. But the rumors among the high command during the war further darkened Carlson’s reputation, even lacking sufficient corroboration. Those who already resented him added the story to their growing list of grievances.

And obviously there was jealousy about the media attention the Raiders had drawn. So this rogue outfit whose maverick commander was too far out of step with the high command was effectively eliminated. It was absorbed into more traditional units. Said one Raider when he got the news, “Gung Ho is dead.” Carlson would never be given another command. Maj. Gen. Merrill B. Twining, who had known Carlson since before the war, wrote in 1996, “Evans Carlson was worthy of a more generous treatment than he received.”

Carlson was kept in staff and training assignments until November 1943, when he was allowed to participate in the invasion of Tarawa as an observer. Still, he managed to involve himself so directly in the fighting that Colonel David Shoup (later Marine Corps Commandant) said memorably, “He may be Red, but he isn’t Yellow.”

In 1944, Carlson talked his way into joining the invasion of Saipan, once again as an observer, which did not stop him from being at the front. He was seriously wounded risking his life to rescue an injured enlisted man. He was sent to hospitals in California to recover and never saw combat again.

The war was over for Evans Carlson, and so was his career. His wounds required extensive and repeated surgery. Between that and the lingering malaria and a growing sense of bitterness and disappointment, he never recovered his health or stamina.

Then in July 1946, Carlson and the Raiders were stunned by the revelation at the Japanese war crimes trials that nine Marine Raiders had been captured on Makin and beheaded—two months after the raid. No one had known that any Raiders had been left behind. Carlson had been certain that every Raider still alive after the battle had reached the safety of the submarines.

On May 27, 1947, Carlson died of a heart attack at the age of 51. General Alexander Vandegrift, then Marine Corps Commandant, attended the funeral at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, but few others were present. The Marine Corps had made no public announcement of the service. When it was over, before the small group of mourners left, a Marine who had served with Carlson in China overheard General Vandegrift say, “Thank God, he’s gone.”

At great personal cost, Evans Carlson had achieved what he set out to do—create an elite special operations force that helped boost the morale of the American people when it was at its lowest point. And he accomplished this on his own terms, in his own way, in defiance of the establishment and its rules.

Duane Schultz is a psychologist and author of more than a dozen acclaimed histories, including Coming Through Fire: George Armstrong Custer and Chief Black Kettle, Crossing the Rapido: A Tragedy of World War II, and Evans Carlson, Marine Raider: The Man Who Commanded America’s First Special Forces.

My cousin, Mason O. Yarbrough of Leeton, Missouri was one of the 18 Marines killed on Makin in August 1942. A MIA team repatriated his remains about 2010. His family opted to bury him in Leeton rather than Arlington Cemetery.