by Eric Niderost

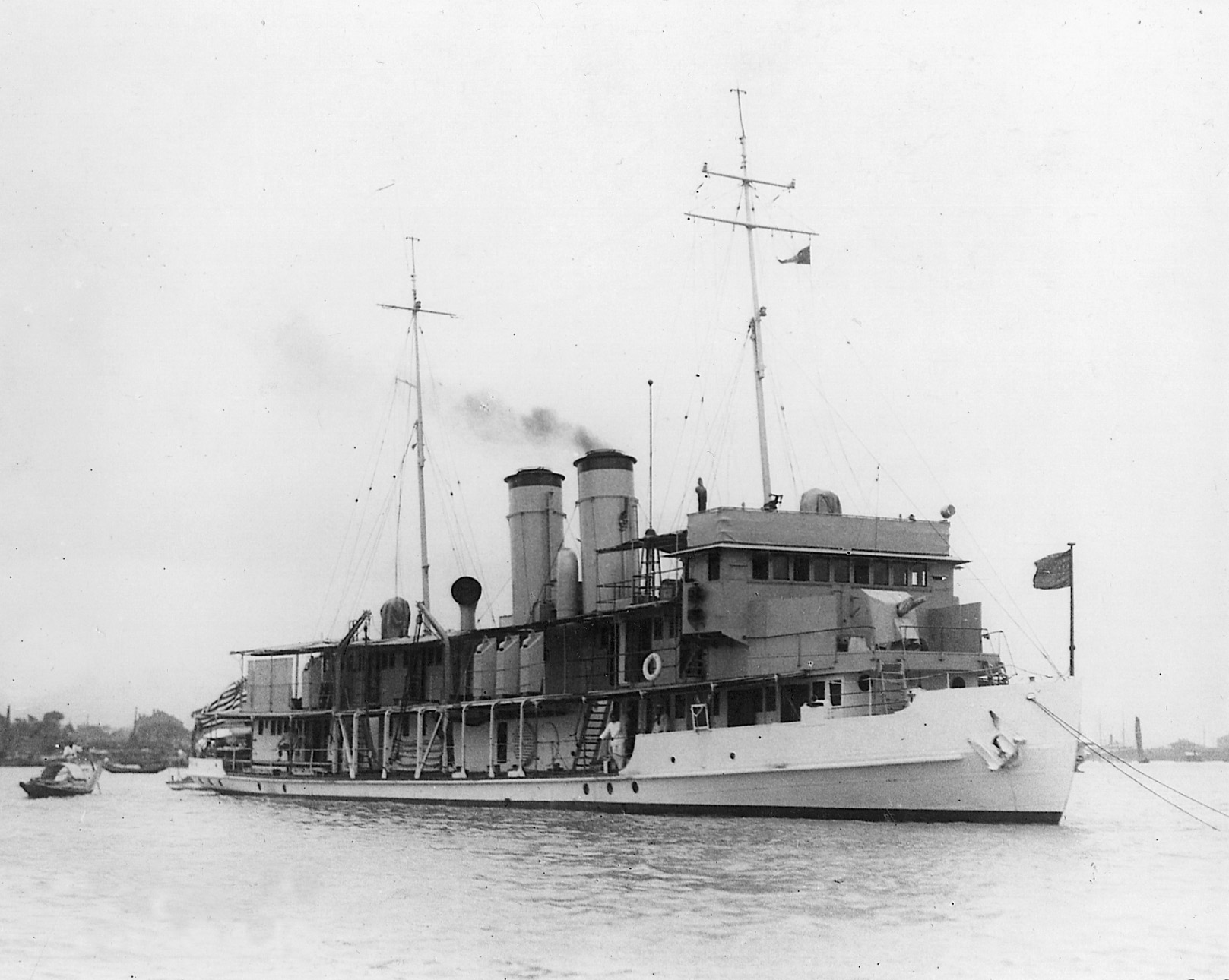

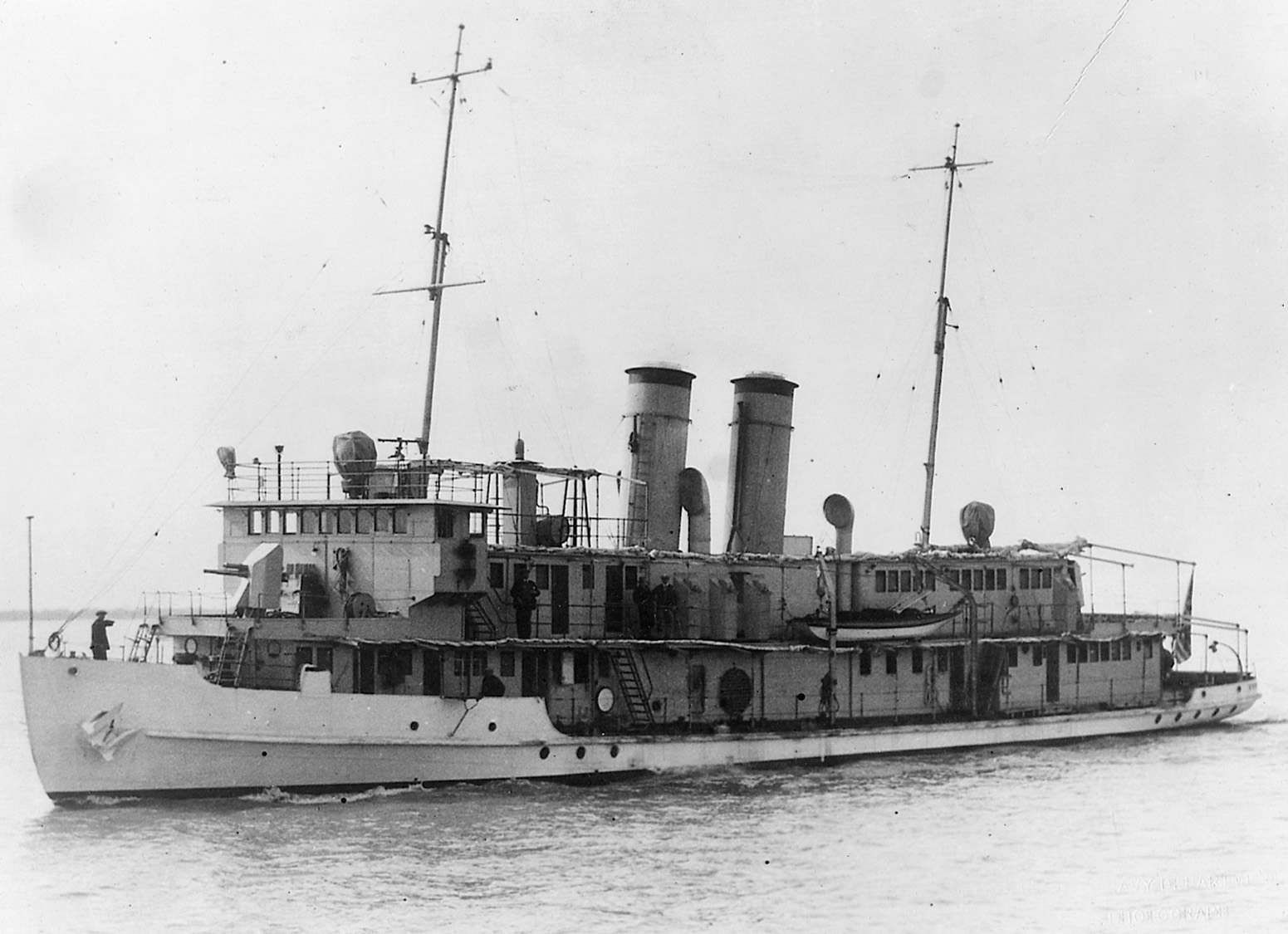

On November 11, 1941, the U.S. Navy gunboats USS Luzon and Oahu were ordered to “make quietly all preparations within the ship for a cruise at sea.” The message, while long expected, was anything but routine. The two gunboats were moored at Shanghai, just off the International Settlement, which made secrecy paramount yet paradoxically impossible to achieve. Spies and informants were everywhere, and the Whangpoo (today Huangpu) River was filled with Japanese warships.

Japan and the United States were on the verge of war, and the Japanese military would welcome the chance to destroy or capture the gunboats if given the opportunity. Yet the odds of any successful escape from Shanghai seemed long. The Japanese controlled the middle and lower Yangtze River Valley and the great river’s outlet to the sea. Even if the gunboats did manage to slip the Japanese net and make it into the East China Sea, they would face a whole new set of challenges.

Japanese Naval Control of the East China Sea

In the summer and fall of 1941 the East China Sea—indeed, much of the Chinese coastline—was firmly under Japanese naval control. The gunboats would have to literally run a gauntlet of warships and patrolling aircraft. The best course of action was to make a dash to the Philippines, then United States territory. If war suddenly broke out en route, or conditions would not permit passage to Manila, then the gunboats would try and make it to the relative safety of British Hong Kong. At the moment, the American gunboats were sitting ducks, so it was far better to attempt a breakout than to passively wait for the inevitable end.

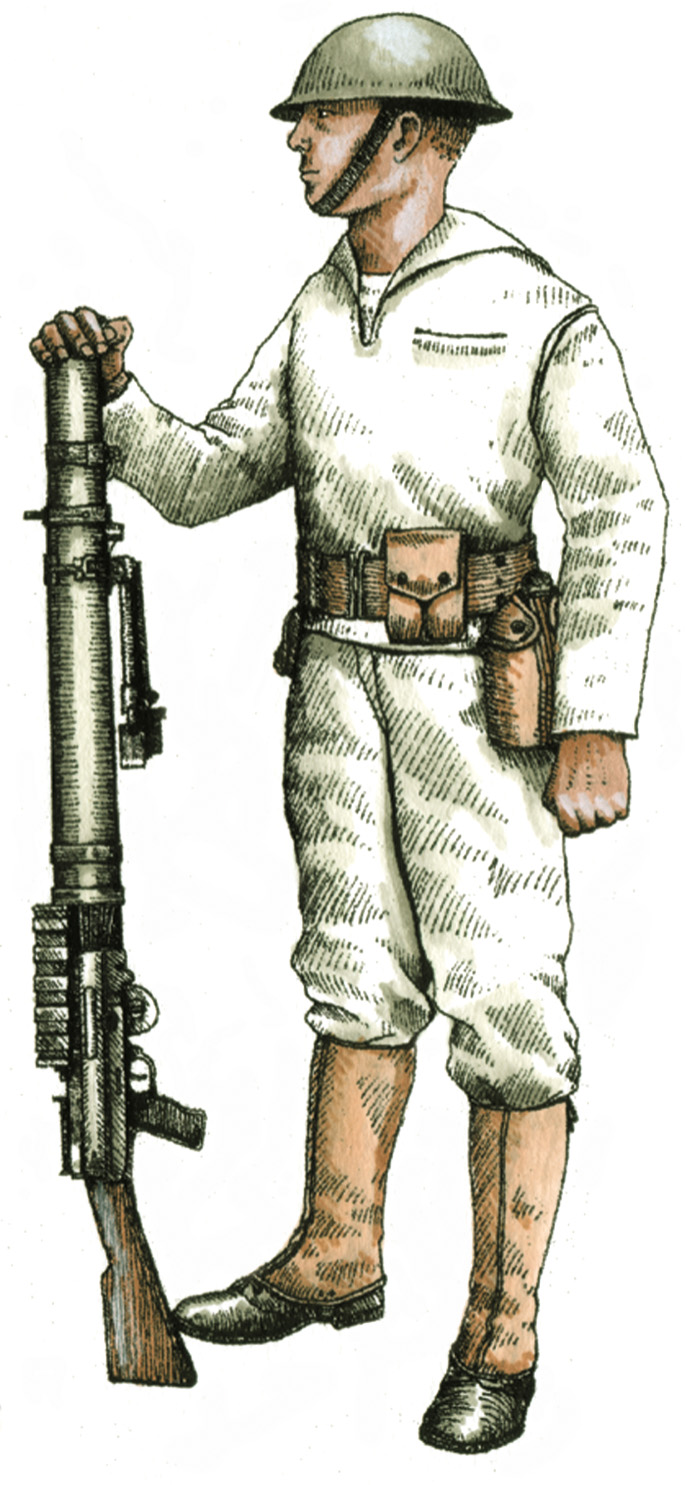

The gunboats were part of the Yangtze River Patrol (YangPat), then commanded by Rear Admiral William A. Glassford (ComYangPat). Glassford, the youngest flag officer in the U.S. Navy, was a handsome and dashing man, and such an Anglophile that he habitually wore knee-length white hose with his uniform shorts. Glassford was convinced the Navy should withdraw from China, an opinion luckily shared by his immediate superior, Admiral Thomas C. Hart. Bureaucracies tend to lead to inertia, so it took a lot of effort and a flurry of memos throughout the summer of 1941 to convince the U.S. State Department that withdrawal was the proper course of action.

YangPat’s Mission

Formally created in 1919, though there had been an American naval presence in China since the mid-19th century, YangPat’s main mission was to safeguard American lives and property. It performed this duty with distinction throughout the 1920s and 1930s. China was in turmoil, struggling to emerge from centuries-long hibernation into the modern world. The transformation into modern statehood would be neither easy nor bloodless.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist (Kuomintang) Party, nominally in control of the central government, battled both Communists and petty warlords for supreme power. Technically, the Yangtze River Patrol was part of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, an amorphous, scattered body whose main base was in Cavite, the Philippines. The YangPat sailors were a breed apart, self-styled “River Rats” or “Old China Hands” who took pride in themselves and their sturdy, flat-bottomed river craft.

The Most Colorful, Cosmopolitan City on Earth

In the 1920s and early 1930s, Shanghai was the most colorful, cosmopolitan city on earth, a blend of east and west whose legend resonates to this day. The International Settlement was Shanghai’s commercial heart and center of foreign influence in the region. It had been created in the 19th century when Western powers had forced China to open its doors to foreign trade. The International Settlement and the neighboring French Concession were literally another universe, part of China yet not subject to Chinese law.

Shanghai’s heart was the Bund, a mile-long waterfront that hugged the broad sweep of the Whangpoo. Sleek black sedans carried British businessmen to work or to the exclusive Shanghai Club, and character-festooned double-decked buses bludgeoned their way through traffic, narrowly missing sweating coolies pulling rickshaws filled with gawking tourists or off-duty foreign servicemen.

“Perennial Privates With Disciplinary Records a Yard Long”

Duty in China was considered a plum assignment in the mid-1930s. Prices were cheap, and even a common sailor or marine’s meager pay would go a long way. Many bars and cabarets where drinks and the companionship of beautiful Chinese and White Russian ladies were readily available to servicemen.

American bluejackets and marines usually found themselves elbow to elbow with servicemen from other countries, with predicable results. It was said that many, though not all, marines in the early 1930s were “perennial privates with disciplinary records a yard long.” They “fought … French, English, Italian and American soldiers and sailors in every bar in Shanghai.”

Nanking Road: a Shopper’s Paradise

Most of these altercations were a means of letting off steam, momentary quarrels that were considered good-natured recreation by all concerned. Shanghai’s famed Sikh policemen, dubbed “red heads” by local Shanghaiese because of their red turbans, sometimes were called in to restore order. British marines, always loving a “bloody good scrap,” would invite their leatherneck opponents for another round of drinks once “peace” was declared.

Not everyone engaged in drunken revels while off duty. Nanking (now Nanjing) Road was a shopper’s paradise where marines and sailors freely bought silks, kimonos, teakwood chests, and ivory, all earmarked for stateside after tours of duty ended. In April 1938, enlisted men of the 4th Marines were presented with a club that was second to none. This 4th Marines Club included a Noncommissioned Officer’s Bar, Private’s Bar, a three-lane bowling alley, billiards, gymnasium, library, restaurant, movie theater, ballroom, and dining and private rooms.

Chinese servants did most of the menial work, which was one of the reasons why Shanghai was considered such a “cushy” assignment. Servants cleaned rooms, did the laundry, and even shined shoes. Chinese cooks, mess boys, and firemen in engine rooms were a common sight aboard American gunboats. Officers were served by mess boys, who made sure that there was a freshly ironed uniform at hand, together with hot water, a razor, and a steaming cup of coffee. No early morning detail was overlooked—even toothpaste would be squeezed on toothbrushes.

Internecine Strife Within the Country

Yet, China could be hazardous, and occasionally a sailor would be killed or wounded while on duty. The country was tearing itself apart with internecine strife, and the gunboats provided a refuge for American missionaries and other U.S. citizens. Lt. Cmdr. R.A. Dyer of the USS Panay remarked in 1931, “Firing on gunboats and merchant ships have [sic] become so routine that any vessel traversing the Yangtze River, sails with the expectation of being fired upon.”

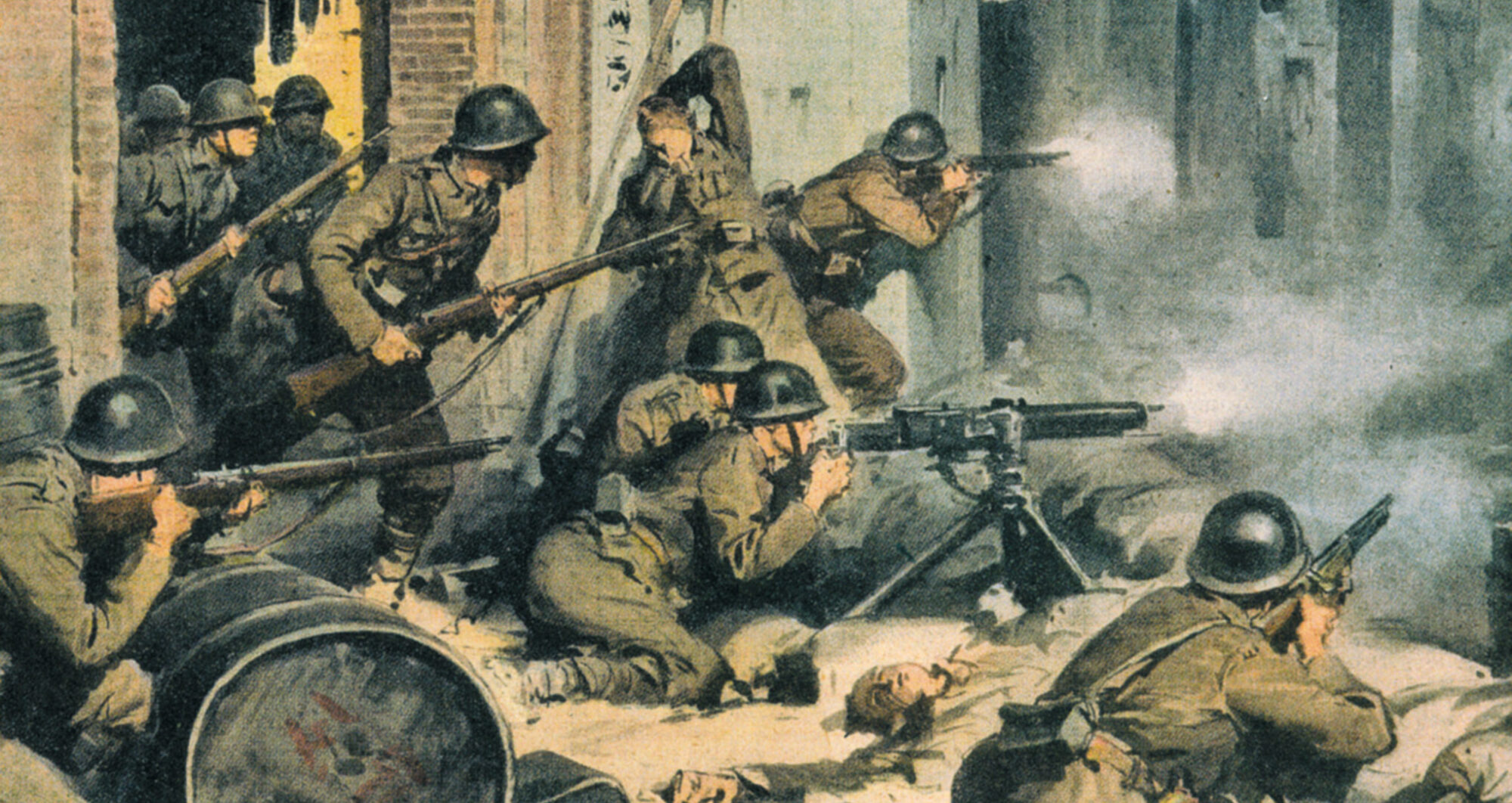

These occasional hazards notwithstanding, Shanghai was still the place to be in the early 1930s. The great metropolis on the Whangpoo was booming, its economy scarcely touched by the worldwide Great Depression. In a very real sense Shanghai’s Golden Age, the period that remains a legend to this day began to fade in 1937, when the Japanese launched their full-scale invasion of China. True, there had been some brief but bloody fighting in 1932 between the Japanese and Chinese in Shanghai’s Chapei district, but the Japanese withdrew and the city quickly rebounded.

This time, the Japanese were playing for higher stakes, nothing less than the conquest of the entire country. Rabid ultranationalists in the military, tough and utterly ruthless, gained the upper hand over Japan’s civilian politicians. They saw the Japanese as racially and culturally superior to all other Asians, and they resented what they saw as Japan’s “second-class” position in the Pacific vis-à-vis Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States.

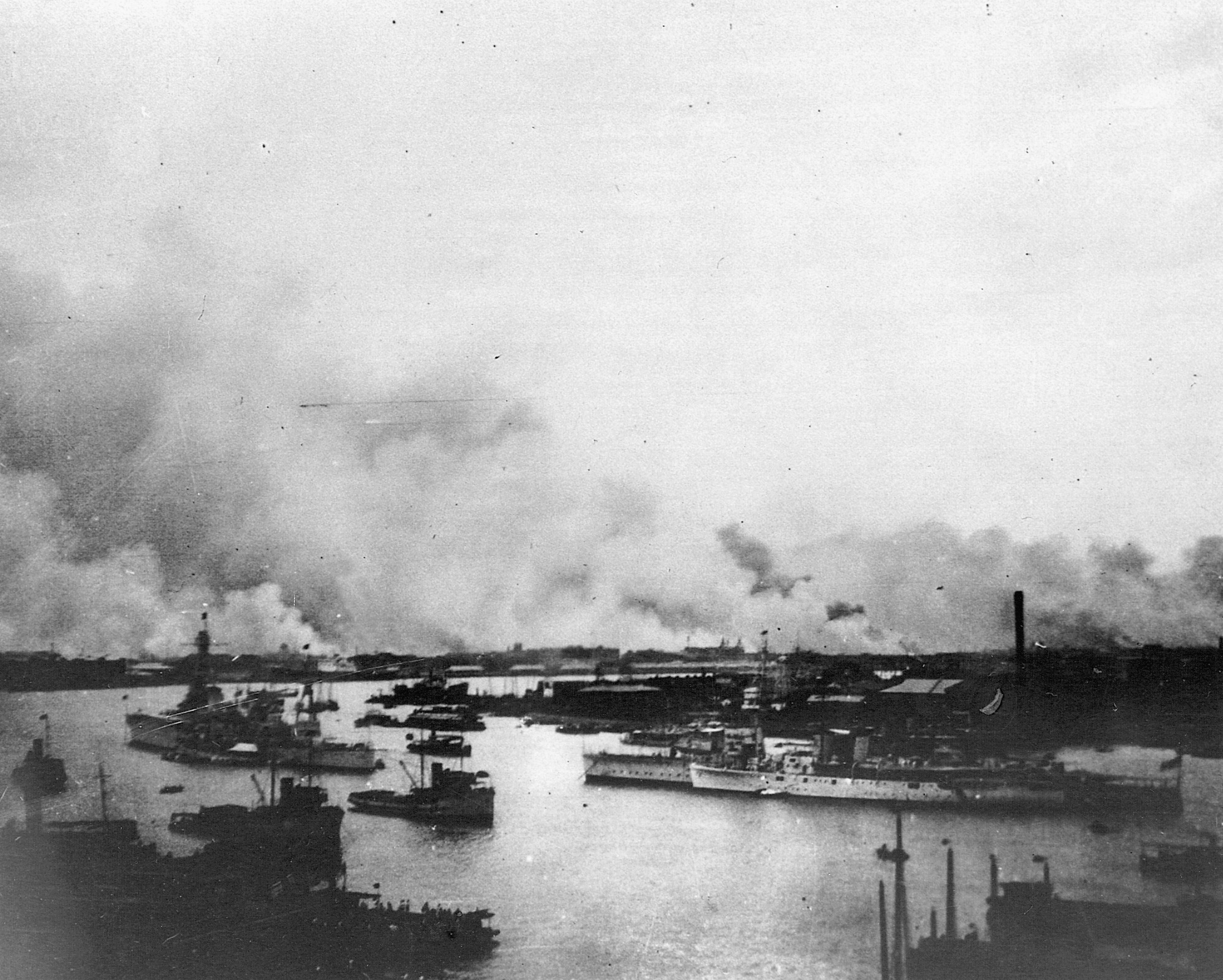

A Forced Retreat Up the Yangtze

The Chinese fought a heroic if ultimately futile holding action at Shanghai for some three months but eventually were forced to retreat up the Yangtze River. Nanking (now Nanjing) fell to the Japanese in December 1937. Enraged by continuing Chinese resistance in the face of overwhelming superiority, the Imperial Japanese Army killed an estimated 300,000 people in what was later called the “Rape of Nanking.” Troops went berserk, fiendishly inventing new and terrible tortures to inflict on their victims. Perhaps 20,000 Chinese women were raped in this holocaust.

The Americans gunboats on the Yangtze performed many vital tasks during this period. On September 19, 1937, U.S. Ambassador Nelson Johnson received a message from Vice Admiral Kiyoshi Hasegawa, commander of Japan’s Third Fleet, that Nanjing was going to be bombed on September 21. The warning, which was dispatched to all foreign diplomatic missions, advised an immediate evacuation of all diplomatic staff. Johnson and the American mission to China boarded the gunboat USS Luzon, then moored in the Yangtze River, on September 20.

“Waiting for Hell to Descend”

The ambassador remained aboard Luzon throughout the 21st, waiting for “hell to descend.” When the entire day passed without incident, Johnson resolved to return to shore the next day, since conditions on the gunboat “were not conductive to the proper functioning of an embassy.” Japanese bombers appeared on the morning of September 22, turning parts of the Chinese capital into a raging inferno. Johnson and his staff watched the horrific spectacle from the relative safety of the Luzon. Once the “all clear” was sounded, the ambassador returned to the American embassy.

As the Japanese advanced up the Yangtze, Johnson followed Chiang Kai-shek’s retreating Chinese government. In November 1937, the ambassador boarded Luzon for Hangkow (Hangkou), some 400 miles upriver. But it seemed nothing could stop the Japanese juggernaut. The Chinese abandoned Hangkow on October 25, 1938, but the Japanese Imperial Army did not actually take the city until four days later. In the interval, all was chaos, so USS Guam landed two officers and 22 men to go ashore and guard the American oil installations of Texaco, Asiatic Petroleum, and Standard-Vacuum against looters.

The International Settlement as Neutral Ground

A few months earlier, on August 3, 1938, Johnson was aboard USS Luzon for the 750-mile, seven-day journey to Chungking (today Chongqing), the newest Chinese capital. The Luzon was accompanied by sister gunboat USS Tutulia, inevitably nicknamed “Tutu” by her crew. The “Tutu” carried embassy cargo that was considered vitally important, including 40 cases of beer. After all, Chungking was a very remote location, and the embassy was going to be “marooned” there for the foreseeable future!

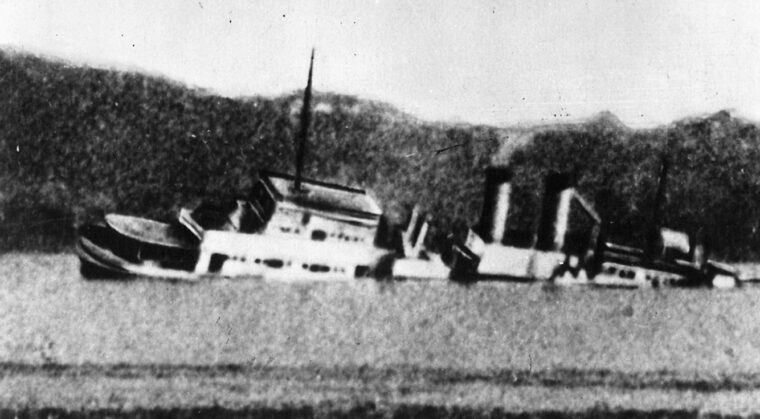

In retrospect, the years 1937 to 1941 have an almost surreal quality to them. By 1940, it was clear to most on-scene China observers that Japan and the United States were on a collision course, but for the most part the diplomatic niceties were observed. There were, however, some serious incidents along the way. On December 12, 1937, Japanese planes attacked the American gunboat USS Panay in the Yangtze River. Two sailors were killed and many more wounded, but hasty Japanese apologies and a large indemnity defused the situation and averted war.

Shanghai’s International Settlement was neutral ground and as such it was the perfect stage for “showing the flag” and impressing rivals with benign displays of military might. There was an atmosphere of surface cordiality, and this was especially true of the officer caste. Whatever the nationality, officers were by definition gentlemen who shared many of the same responsibilities and privileges of rank. When an American naval officer arrived in Shanghai, he was expected to make courtesy calls to his foreign opposites, and they were expected to return the compliment.

Locking Horns With Japanese High Command

After 1937, these courtesies continued, but the dramatically altered political climate began to strain relations. Shanghai’s International Settlement was by late 1937 a neutral island in a Japanese sea. The International Settlement was small, about 8.73 square miles, or 5,583 acres. The adjoining French Concession was even smaller, just under 4 square miles in circumference. In a sense, the International Settlement was even smaller that it was on paper because its Hankow District, just across Soochow (Suzhou) Creek, was so heavily Japanese it was nicknamed “Little Tokyo.”

With the middle and lower Yangtze Valley under direct Japanese control, the U.S. Yangtze River Patrol’s mission became harder and harder to fulfill. Individual Japanese officers, particularly naval officers, remained friendly, but increasingly an iron fist was replacing the velvet glove.

With Ambassador Johnson ensconced some 1,400 miles up the Yangtze in Chungking, senior American naval officers found themselves diplomats by default. Admiral Harry E. Yarnell, commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, was the first to lock horns with an increasingly arrogant Japanese high command.

Reading the Handwriting on the Wall in 1939

On December 21, 1937, Admiral Hasegawa sent a letter to Yarnell explaining, ”It is the desire of the Japanese Navy that foreign vessels including warships will refrain from navigating the Yangtze except when an understanding is reached with us.” The missive had an undertone of command, something Yarnell would not tolerate. Besides, the Japanese could not abrogate American treaty rights, however they might bluster or bully.

Admiral Yarnell, tongue firmly in cheek, called Hasegawa’s demand a “suggestion,” a “suggestion” the American C-in-C was not about to follow. Yarnell wrote to Hasegawa in a polite but firm manner, saying, “We cannot … accept the restriction … that foreign men-of-war cannot move freely on the river without prior arrangement with the Japanese and we reserve the right to move these ships whenever necessary without notification.” Yarnell’s letter was cosigned by senior officers of the British, French, and Italian navies.

By 1939, the handwriting was on the wall, at least to senior American officers stationed in China. Admiral Thomas C. Hart succeeded Yarnell as commander, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, on July 25, 1939. Yarnell had been respected by his peers and by the international community at large, and many were aghast at his removal. Hart and Yarnell had been midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, and the outgoing chief knew the command was in good hands. When asked about his replacement, Yarnell would simply reply, “Tommy Hart is a stout fellow.”

This article is from the September 2005 issue of WWII History Magazine. If you would like to read the rest of this and other articles, visit our order page to see which digital editions we have on offer.

My my father Carl Adam Puswaskis was a Marine on the USS Ashville from 31 thru 33 I have dozens of photos, documents, memorability, and a diary that my father compiled while on the “Patrol”.

Why has this not been turned into a movie? This is something that would make an outstanding movie if done right.

Try Sand Pebbles staring Steve McQueen… Great movie.