By John Walker

As long afternoon shadows rolled across the prairie near the confluence of the Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River in eastern Texas on April 21, 1836, two armed camps—one a small Texan force, the other a 1,400-man-strong Mexican army—lay within a scant 1,000 yards of each another. All was calm in the Mexican camp during siesta hour. The army’s commander, President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, was so convinced that no attack was imminent that, even with his men virtually within sight of the enemy, he had neglected to deploy pickets. Arms stacked, Santa Anna’s infantrymen slept, talked, cooked meals, or played cards while their cavalry comrades unsaddled their horses and let them graze or rode them bareback to the water’s edge.

The drowsy stillness was suddenly shattered at 4 pm, when some 930 Texan soldiers came charging forward on foot and horseback, hidden by the almost waist-high prairie grass, and launched a devastating surprise assault against the larger Mexican force. The climactic battle of the war for Texas independence was about to be fought. For General Sam Houston’s ragtag “Texian” army, it was now or never—the fate of the nascent Republic of Texas hung in the balance.

The Anglos of Coahuila y Tejas

During the early years of the 19th century, droves of Anglo-American colonists had settled in Texas, then part of the northern Mexican province of Coahuila y Tejas. They were given generous grants of land in return for agreeing to become Mexican citizens, abide by the laws, and practice Catholicism. By the late 1820s, however, the Mexican government began restricting American immigration. In 1829 the comparatively liberal Federalist government was displaced by the Centralists, who voided much of the nation’s 1824 Constitution that had granted a great deal of autonomy to regional governments in Mexico’s provinces. When the Centralists attempted to enforce their new policies in the north, relations between the Mexican government and restive American colonists quickly deteriorated.

Outright rebellion broke out in 1835, after Santa Anna rescinded the constitution altogether and assumed dictatorial control over the nation. After capturing a few small outposts and defeating the small Mexican garrisons in the area, the Texans, side by side with many Tejanos, ethnic Mexican residents of Texas, declared their independence on March 2, 1836. It was a bold move, considering the fact that only about 30,000 colonists lived there, sharing the land with more than 20,000 Native Americans, at least half of whom were unfriendly. The Republic of Mexico, although in a constant state of revolutionary turmoil, numbered eight million people.

Hundreds of volunteers from the United States flocked into the fledgling Republic of Texas to aid the colonists in their quest for independence. Two regiments of volunteers were organized to augment the regular Texan army commanded by Houston. The Kentucky Rifles, a company raised in Cincinnati and northern Kentucky by Sidney Sherman, was the only group in the Texan army that wore formal uniforms. The New Orleans Greys, another company raised in the United States, marched to San Antonio de Bexar to serve under a regular Texas army officer. Other volunteers, including both Texan and Tejano colonists, formed companies to defend various places that might be targets of Mexican intervention. One company was composed entirely of Tejanos commanded by 30-year-old Captain Juan Seguin, son of one of the wealthiest and most respected patriarchs in Texas, Erasmo Seguin. The Seguins, father and son, held an understandable grudge against the Mexican government. When Brig. Gen. Martin Perfecto de Cos, Santa Anna’s brother-in-law, occupied San Antonio de Bexar in late 1835, his soldiers mistreated the elder Seguin. As a result, the influential clan became staunch revolutionists. Erasmo Seguin turned over the resources of his large ranchos around San Antonio to the rebels and made large contributions of food, horses, and mules to the insurgents.

Santa Anna personally led a force of over 6,000 Mexican regulars on a treacherous 800-mile winter march through the northern Mexican deserts into Texas to crush the insurrection. El Presidente had already brutally suppressed widespread rebellions across Mexico in Tampico, Yucatan, and Zacatecas. The Mexican army was a mixed force of regular infantry and cavalry units as well as reserve infantry battalions and prisoners from the Yucatan impressed into the army. Santa Anna’s line troops were armed with .75-caliber “Brown Bess” muskets, the standard-issue British infantry firearm since 1722. His elite riflemen, known as cazadores, were issued the .61-caliber Baker rifle, a more accurate firearm at longer ranges than the Brown Bess musket. Mexican cavalrymen were armed with British Paget carbines, sabers, and lances. Several of Santa Anna’s general officers were foreign mercenary veterans, including Brigadiers Vicente Filisola of Italy, Adrian Woll of France, and Antonio Gaona of Cuba.

The Goliad Massacre

El Presidente was supremely confident as his army headed north. The rebels, to him, were merely a horde of mercenaries and opportunists looking to rape and plunder his native country. He would do to them what he had done to the insurrectionists in Zacatecas. “The invaders,” he wrote, “were all men who, moved by the desire of conquest, with rights less apparent and plausible than those of Cortes and Pizarro, wished to take possession of the vast territory extending from Bexar to the Sabine, belonging to Mexico. What can we call them? How shall they be treated? All the existing laws marked them as pirates and outlaws.” The appropriate punishment for pirates was death, he said, and death they would receive. Santa Anna informed Brig. Gen. Joaquin Ramirez y Sesma, commander of his advance infantry brigade, of the policy to be adopted toward the rebels: “The foreigners who are making war against the Mexican nation, violating all laws, are not deserving of any consideration, and for that reason no quarter will be given them.” Besides, he said with a grim smile, “If you execute your enemies, it saves you the trouble of having to forgive them.”

Santa Anna entered the provincial capital of San Antonio de Bexar and laid siege to the Alamo, a small redoubt defended by 190 hardy volunteers under the command of Colonel William B. Travis. Rather than simply surrounding the fortress with a small force of his own, the vainglorious dictator, who styled himself the “Napoleon of the West,” insisted on attacking, sustaining heavy losses in the process—some 600 Mexicans were killed or wounded in the subsequent attack. Santa Anna executed the only seven survivors of the battle, including former U.S. member of Congress David Crockett of Tennessee, and burned the bodies of all the defenders.

Another Mexican force led by the capable General Jose Urrea, which constituted the right wing of Santa Anna’s army, defeated a second Texan force under Colonel James Fannin near Goliad and accepted the surrender of some 390 soldiers. Santa Anna callously ordered their wholesale execution, much to the dismay of Urrea, who had petitioned for their parole to New Orleans. Urrea rode away, leaving the prisoners in the care of an underling. The prisoners were marched onto the prairie and massacred on Palm Sunday, March 27, 1836. The atrocity served to further inflame Texan and Tejano colonists, as well as the people of the United States. Santa Anna cynically spared Goliad’s medical personnel and sent them to care for his wounded at the Alamo.

Withdrawal of the Texans

After hearing of the Goliad massacre, Houston retreated slowly eastward to the disappointment of his eager volunteers, who wanted to stand and fight, and Texas President David G. Burnet. Burnet, a fierce critic of Houston, sent the general frequent dispatches imploring him to turn and fight. Houston’s military experience and knowledge of Indian warfare, however, convinced him that the only chance for victory for his outmanned, untrained little army was to lead the enemy toward the East Texas woodlands, where he had more population to draw on; the long marches would wear down the Mexican columns and stretch their lines of supply. Houston also needed time to drill at least the basic rudiments of warfare into his undisciplined troops.

Afraid that Mexican forces were rapidly approaching, Burnet and his cabinet abandoned the capital at Washington-on-the-Brazos and hastily crossed the prairie toward the Gulf of Mexico, eventually reestablishing government functions in Galveston. In the wake of the retreating army and government, thousands of panicked colonists, both Texan and Tejano, fled eastward in what became known as the “Runaway Scrape.” Men, women, and children packed what belongings they could into wagons and carts, onto horseback or on their own backs, and fled in terror across the rain-soaked countryside, moving eastward toward the Louisiana border.

Santa Anna pursued Houston’s ragtag army, which had grown to about 1,180 men, and devised a trap in which three columns of Mexican troops would converge on the Texan force and destroy it. The northern wing, about 800 men commanded by Gaona, was ordered to destroy all settlements in its way and push toward the Louisiana border. The main, or middle, column was spearheaded by another 800 men under Sesma. It aimed at the towns of Gonzales on the Guadalupe River and San Felipe de Austin on the Brazos River. The 2,000-man coastal force, led by Urrea, was to drive about 150 miles along the coast of Texas, the island of Galveston its ultimate objective.

Santa Anna Spread Thin

At this stage of the incursion, Santa Anna amazingly grew bored, regarding the remainder of the campaign as little more than a mopping-up operation (and a lot of work for his firing squads). El Presidente considered returning to Mexico City and leaving the Texas expedition in the hands of his second-in-command, the suave Italian general, Vicente Filisola. Filisola, a professional soldier who did not like the idea of splitting the army into three columns, and Colonel Juan Almonte persuaded Santa Anna to remain in Texas. Deciding to take possession of the Texas coast and seaports, Santa Anna crossed the Brazos River on April 15 and marched rapidly eastward for Harrisburg. When Santa Anna arrived at Harrisburg on the night of April 15, he found it deserted. After setting fire to the town, he and his 750 soldados marched east to New Washington, located at Morgan’s Point on San Jacinto Bay, hoping to trap the fleeing insurgent government with its back to the water.

Santa Anna’s troops came within a hair’s breadth of doing just that. As Burnet and his staff began rowing out to a ship in the bay, a patrol of Mexican cavalry clattered up to the pier and prepared to open fire. Almonte, in command, chivalrously forbade his soldiers to fire; he had spotted a woman, Burnet’s wife, in the rowboat. His attempt to capture the Texan government having failed, Santa Anna decided to find and destroy the only remaining semblance of rebellion left in Texas—Houston and his little band. Supremely overconfident, the dictator had dangerously scattered his forces. The hunter was about to become the hunted.

“The Twin Sisters”

Meanwhile, Houston’s army had received a much-needed gift from the citizens of Cincinnati, Ohio—two six-pound artillery pieces the men dubbed “the Twin Sisters.” Houston crossed the Brazos River on the Yellow Stone steamship and arrived at Spring Creek on April 16. The next day, to the immense gratification of his men, Houston took the road to Harrisburg instead of the road to Louisiana. After a two-day march of 60 miles, Houston’s little army arrived at Buffalo Bayou. Across the water they could see that Harrisburg had been burned to the ground; Santa Anna had obviously been there first. Houston desperately needed to ascertain Santa Anna’s whereabouts and maneuver him into an advantageous position for battle before he had time to concentrate his forces. Houston’s luck held. His best scout, Erasmus “Deaf” Smith, returned to camp with a Mexican courier who had been captured carrying saddlebags stamped with the name of William Barrett Travis. The bags contained special dispatches to Santa Anna giving the complete disposition of his columns, their strengths, and whereabouts.

On April 19, Houston’s men crossed Buffalo Bayou on crudely built rafts. After leaving 248 sick and ineffective men and guards at a camp near Harrisburg, they crossed Vince’s Bayou on the only available bridge and gained the sea-level plain known as San Jacinto. The field was small—barely three square miles—and roughly triangular. It was bounded on the northwest and northeast by Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River, respectively, and was open to the southwest by the Texas coastal plain. Since neither stream was fordable, the position Houston took up was a virtual dead end except for Lynch’s Ferry, which crossed the San Jacinto River at the northern end of the triangle. Much of the plain was grassy, but there were substantial stands of live oak forest running along the bayou. Houston hid his troops in one of these Spanish moss-covered live oak stands located near the northern end of the virtual island.

About noon the next day, the vanguard of Santa Anna’s 750-man force reached San Jacinto, burning the town of New Washington behind them. Finding himself cut off from Lynch’s Ferry, the dictator took up a position in some live oaks near the southeast corner of the prairie. Houston’s men were well protected within their line of trees, their two six-pounders deployed about 10 yards out on the plain. Mexican gunners unlimbered their one 12-pounder cannon and opened fire on the Texan lines. Santa Anna clearly wanted to draw the Texans out into the open to probe their strength and perhaps provoke an attack. The Texan artillery, under the command of Colonel James Neill, began returning fire.

The artillery duel continued for several hours. In the process, Neill’s hip was shattered by a well-aimed blast of grapeshot. A shot from one of the Twin Sisters damaged the Mexican piece, and as Mexican cavalrymen began drawing it back to safety, Colonel Sherman sallied forth with 50 horse soldiers to capture the enemy piece. He failed miserably, losing two men and several horses. Worse yet, he almost triggered an attack by the Mexicans, prompting an infuriated Houston to take away Sherman’s command of the cavalry and give it to Mirabeau Lamar. A volunteer private in the cavalry, Lamar had distinguished himself in the skirmish, saving the lives of two Texans, including Secretary of War Thomas Rusk, who had joined the army to confer with Houston. Lamar was immediately promoted to colonel by Houston.

The Mexican Camp Swells

Santa Anna withdrew his forces about three-quarters of a mile, placing his army with its back to Peggy’s Lake. His troops spent the rest of the afternoon and night constructing a five-foot-high barricade of trunks, baggage, and pack saddles to serve as breastworks for the infantry. By dawn of April 21, the Mexicans had completed their defenses and braced themselves for an attack by the Texan army. None came.

The tap of a drum at 4 am served as reveille in the Texan camp on April 21. No more than a mile apart from each other on ground located on the cattle ranch of Peggy McCormick, the two armies were eager to end the campaign and its incessant marching. The previous day’s inconclusive skirmishing had only whetted the appetites of those who were hungry for combat. An hour later, the Mexican soldiers were roused from their slumber. Santa Anna stirred briefly at 9 am, when his brother-in-law arrived with 400 of the 500 reinforcements he had ordered. Although his troops were elated at the new arrivals, Santa Anna was furious with Cos. He had told his kinsman to bring 500 of his best foot soldiers from the Velasco area, but Cos had hurriedly pulled less-experienced men from various battalions and hurried his march to San Jacinto. In the final push to reach the field, about 100 men had fallen behind and been abandoned. Since the new arrivals had marched all night, Santa Anna ordered them to stack their arms and get some sleep after taking up positions on the army’s right flank, close to the water. El Presidente retired to his tent while the rest of the army settled down to rest under the oak trees.

Texan scouts had watched as Cos’s column approached from the direction of Vince’s Bridge and notified Houston when they reached the Mexican camp; it didn’t come as a surprise to Houston, as his scouts had captured several of Filisola’s couriers carrying messages indicating he had received his commander’s request for additional troops. Houston now began forming a plan to destroy Vince’s Bridge, which lay about eight miles southwest of Lynch’s Ferry, to deny his enemy further reinforcements and to possibly initiate an attack of his own later that afternoon. The fair, dry weather pleased Houston immensely. “This is going to be a damn good day to fight a battle,” he said happily. The weapons most of his men carried—old, muzzle-loading flintlock muskets—were adversely affected by wet and windy conditions. The Twin Sisters, as well, performed better in dry weather; they had to be ignited with flares. Nature, it seemed, was on the side of the Texans.

At 10 am, Colonel John Wharton, Houston’s adjutant general and another staunch critic of the general, made the rounds through camp, visiting each mess. Although no attack plan had been issued, on his own Wharton exhorted the men: “Boys, there is no other word today but fight, fight! Now is the time!” In the late morning, Houston had Deaf Smith ride out to a rise between the two camps to form an estimate of the size of the Mexican army. Smith and Private Walter Lane rode to within 300 yards of the enemy encampment. Smith took out his field glasses and counted the enemy tents, deducing that Santa Anna’s force numbered about 1,500 men; he and Lane then rode back and shared their information with Houston.

“Vince’s Bridge is down! Fight for your lives!”

Shortly before noon, Houston held a council of war with Colonels Sherman and Edward Burleson; Lt. Cols. Henry Millard, Alexander Somervell, and Joseph L. Bennett; and Major Lysander Wells. Two of the junior officers voted to attack the enemy in his position, while the others favored waiting for Santa Anna to attack. The main concern of the officers opting for a defensive posture was that most of the attack would come over open ground, where the attackers would be vulnerable to Mexican cannon and musket fire. The Texans were also woefully short on bayonets. Houston withheld his own views, but later, fearing the specter of additional reinforcements reaching his foe, decided to attack the Mexican camp that afternoon. He submitted his daring plan to Secretary of War Rusk, who approved it. Houston made the rounds of the camp, asking the men if they were ready to fight, and was answered in the affirmative. By 3 pm, convinced his foe was not ready to attack, Houston ordered the troops to be assembled. Wrote one Texan, “There was a rejoicing throughout the camp.” Another wrote “The announcement of the decision to fight acted like electricity.”

By 3:30 pm, the Texan army was formed into lines of battle for the impending assault, screened from the enemy’s view by trees and a slight ridge that ran across the open prairie between the opposing armies. Deaf Smith and six volunteers rode past the left flank of the Mexican army unmolested and made their way along Buffalo Bayou to Vince’s Bridge. Unable to completely burn the bridge, Smith and his men destroyed the remnants, sending what was left of the structure falling into the bayou before heading back to the Texan camp, thus cutting off the avenue for further reinforcements to Santa Anna’s army. Either in encouragement or panic—perhaps some of both—Smith rode up to his comrades, shouting, “Vince’s Bridge is down! Fight for your lives!”

Caught Unaware

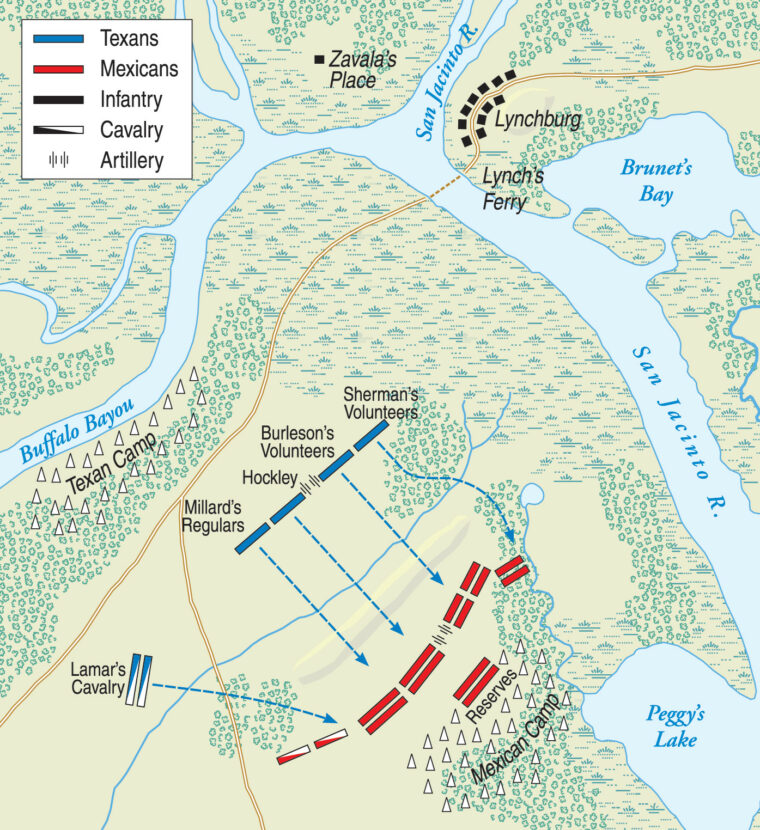

Houston went to work deploying his army for battle. On the Texan left, closest to the river, he put the 2nd Regiment of Texas Volunteers, 330 infantrymen under the command of Sherman. Next in line came the unit he considered the backbone of his army, the 1st Regiment, 386 men, under the command of the old Indian fighter, Ned Burleson. In the center of the line were the Twin Sisters and 32 artillerymen commanded by Lt. Col. George Hockley. On their right came the 92 men of the regular Texan army under Millard; the band, a drum and three fifes, marched with the regulars. On the far right, under the newly promoted Lamar, were the 63 troopers of Houston’s small cavalry force.

The army stood in two thin lines stretching some 900 yards, each man ready for action, armed with flintlock muskets, pistols, swords, and bowie knives. Houston mounted a giant white stallion named Saracen and rode along the lines, inspecting the army that would decide the fate of Texas. The inspection ended with the 2nd Regiment on the far left. Houston told Rusk to stay with Sherman’s regiment as the attack unfolded; when the armies made contact, Rusk was to ride over to the center and report to Houston. The plan called for Sherman’s men to move against the Mexican right, which lay in a grove of trees, its movement screened from the rest of the army. Houston had decided to outflank the Mexican left with his cavalry, stretching his troops even thinner.

At about 4 pm, Houston took up a position in the center of the line, a few yards out front, sword in hand, and waved his army forward. Some 930 Texan volunteers emerged from the timber, each of the units in column, the soldiers at trail arms. The Texans emerged from the thin woods and moved quickly over the ridge in the center of the plain, 500 yards from the Mexican lines. Colonel Pedro Delgado apparently noticed the oncoming Texan line first, and soon a cazadore bugler on the right trumpeted a call to stations. Brig. Gen. Manuel Fernandez Castrillon, a competent officer who had been at odds with Santa Anna over the location of the camp, quickly recognized the gravity of the situation and shouted for a stout defense to be conducted. His cries aroused some of the lethargic defenders, but others continued to lie about. With the enemy just minutes from reaching their barricade, the bulk of Santa Anna’s 1,400 soldiers still were not aware that the Texans were actually attacking their camp.

The Confusion of Battle

Castrillon and Lieutenant Ignacio Arenal rushed out of their tent to take charge of the lone Mexican cannon. At the same time, Delgado rushed about, trying to rally fleeing dragoons as they raced for the trees beyond the camp and spanking scared infantrymen on the backsides with his saber in an effort to force them to fight. All efforts were in vain. “They were a bewildered and panic-stricken herd.” Delgado recalled. “His Excellency running about in the utmost excitement wringing his hands and unable to give an order. Some cried out to commence firing; others to lie down to avoid grape shots. Among the latter was his Excellency.”

A few of the men on the Mexican outpost line began firing their muskets, but in their surprise and excitement they fired high, and few of the Texans were hit. Houston’s men continued their advance with their cannon out ahead of the infantry and Lamar’s cavalry swinging around to the right. At a range of 200 yards, the Twin Sisters unlimbered and swung about, firing improvised shrapnel rounds of chopped-up horseshoes and gouging holes in the Mexican breastworks. As the Texan line swept forward, the cannons were manhandled with rawhide ropes to within 70 yards of the enemy’s works and opened fire once more. The Texans moved swiftly across the field. From a quickstep, the emboldened attackers broke into a trot; the neat, parallel lines merged sloppily into one great mass of roaring men.

Houston, 20 yards out in front, realized that he had little actual control over the frenzied body of soldiers. He endeavored, however, to stop the men long enough to send one standing, massed volley against the enemy lines. Even that simple maneuver was too much to comprehend for some of Sherman’s men on the Texas left, who discharged their weapons indiscriminately. An enraged Houston, who wanted every cartridge to count, roared across the field, “Hold your fire, goddamn you, hold your fire!” At this juncture, the usually unflappable Thomas Rusk was unable to contain himself. He galloped hard for the Texan left, screaming, “If we stop we are cut to pieces. Don’t stop—go forward—give them hell!”

“Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!”

Sherman’s 2nd Regiment made contact first, managing to sneak up through the timber, just inland from the marshes and river. Cos’s men, on the Mexican far right, were caught utterly by surprise. Alphonso Steele, a private in Sherman’s unit, later wrote, “When within 60 or 70 yards we were ordered to fire. Then all discipline, as far as Sherman’s regiment was concerned, was at an end. We fired as rapidly as we could. As soon as we had fired, each man reloaded and he who got his gun ready first moved on without waiting for orders.” The Mexican defenders, at least during the initial moments of the attack, managed to put up a vigorous defense, their makeshift breastworks offering some protection for their riflemen. “Their breastworks were composed of baggage, saddlebags, and brush, in all about four or five feet high,” remembered James Winters of Sherman’s regiment. “There was a gap eight or ten feet wide through which they fired the cannon.”

Sherman’s eager troops crashed heavily into the right wing of the Mexican line. Soon the smoke from the cannon and the small arms made it almost impossible to see clearly. In his report after the battle, Houston credited Sherman with being the first to shout, “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” The cry was soon echoing up and down the Texan line. A member of Seguin’s company, Sergeant Tony Menchaca, took up the cry in Spanish, his loud, impassioned voice striking terror into the Mexican troops just yards away. As he had been ordered, Rusk left Sherman’s unit and rode out in front of the battle line to report to Houston, telling his commander, “The 2nd Regiment has made contact with the enemy in gallant style.” Houston and Rusk were both exposing themselves to a dangerous crossfire; at one point, Houston narrowly avoided being struck by his own artillery.

The Mexican resistance was stoutest under Castrillon, around the 12-pounder cannon. The piece was discharged three times and was being loaded for a fourth shot when a round from one of the Texan guns struck the cannon’s water bucket, stunning some of the gunners and putting the others to flight. Castrillon tried desperately to keep the cannoneers from fleeing, to no avail. Five Texan infantry companies swarmed over the area around the 12-pounder, killed any remaining crew members, and captured the piece. Attacker Walter Lane wrote of the episode, “As we charged into them, the general [Castrillon] commanding the Tampico Battalion, their best troops, tried to rally his men but could not. He drew himself up, faced us, and cried out in Spanish, ‘I’ve been in forty battles and never showed my back. I’m too old to do it now.’” Rusk yelled to his men not to shoot Castrillon, and even knocked up some of the Texans’ guns, but others ran around him and riddled the Mexican general with musket balls.

Blame to Share

Santa Anna’s personal secretary, Ramon Caro, felt that the president later placed unfair blame on Castrillon for the surprise attack; Caro believed the commander in chief was equally liable for the lack of vigilance against an enemy that the day before had made a false attack to feel out the Mexicans’ strength. Santa Anna claimed that he was sleeping soundly when he was awakened by the sound of the firing. He said he became aware immediately that his forces were under attack and that there was “unexplained disorder. The enemy had surprised our advance posts.” He also claimed that he dispatched units to reinforce the Mexican troops holding their line and to check the oncoming Texans. Caro dismissed his commander’s assertions out of hand. “The principal movement of the enemy was the complete surprise,” he wrote. “The rest of the engagement developed with lightning rapidity, so that by the time he [Santa Anna] reached our front line it had already been completely routed.”

Once Sherman’s regiment swept into the Mexican camp, the breastworks no longer offered any protection. Few men had bayonets, so their firearms became war clubs once the opportunity to reload was lost. Wrote Lane: “In a second we were into them with guns, pistols, and bowie knives. In a short time, they were running like turkeys, whipped and discomfited.” When Houston and Rusk were about 40 yards from the enemy’s works and almost directly in front of the Mexican artillery, a sudden volley of shots struck and killed Houston’s horse, slamming the uninjured commander to the ground. After remounting, Houston made it almost to the breastworks before he was hit just above the left ankle by a three-ounce rifle ball and his second horse was shot from under him. After he was given another mount, the painfully wounded Houston charged boldly among the enemy’s tents. The Texan cavalry, advancing on the right, tried to block the enemy’s only exit from the battlefield, but Lamar had too few men to accomplish the task. His troopers cut a swath among the enemy, however, and the riderless horses of dead and wounded Mexicans added greatly to the swirling confusion among the defenders.

Although some of the Texans had been shot down during the advance, the larger number of casualties occurred in front and inside the enemy’s campground. Moving forward under heavy fire, Burleson’s 1st Regiment suffered twice as many casualties as Sherman’s. Sherman’s and Burleson’s regiments, together with Hockley’s two cannon, Millard’s regulars, and Lamar’s cavalry, all came together in shredding the Mexican camp with a deadly fury. Houston was highly visible at all times, and his men were unaware he had been seriously wounded until much later. “Where our two regiments came together, and the Mexicans rallied,” wrote Stephen Sparks, “about ten acres of ground was literally covered with their dead bodies.” The Mexican army consisted of professional soldiers, but they had been trained to fight in ranks, exchanging volleys with their opponents; they were ill-equipped to fight well-armed Anglo-American and Tejano frontiersmen in hand-to-hand combat. Their quick-thinking commander mounted a horse and fled toward Buffalo Bayou just before the camp was overrun.

“I applaud your bravery. But damn your manners.”

Organized Mexican resistance ended after a mere 18 minutes, but the killing was far from over. The massacres at the Alamo and Goliad were too fresh in the men’s minds to be forgiven. Mexican troops who threw down their arms and begged for surrender received the same degree of mercy that the Texans’ had received earlier—none. By this time, Cos’s reinforcements had been routed on the Mexican right, the survivors crowding the Mexican center and adding to the confusion. The men of Burleson’s regiment had overrun the breastworks in the enemy center, rapidly killing and wounding any Mexican soldiers who chose to stand and fight. After the initial onslaught the Texans continued, chasing the horrified fugitives and shooting them down in droves, killing any unfortunate wounded they happened to come across. About 50 yards behind the Mexican camp lay a tidewater bayou and a small body of water, called Peggy’s Lake after Mrs. McCormick. There, according to Private Washington Winters, “occurred the greatest slaughter. The Mexicans and horses killed made a bridge across the bayou.”

Between 200 and 300 Mexican soldiers jumped into the water and were attempting to reach a small island several hundred yards out into the lake; Texan riflemen cut them down as they swam. Out of ammunition and without time to reload, some Texans splashed into the water with their bowie knives and hatchets to exact revenge. Wharton rode up and ordered the riflemen to stop firing, but they refused. With their men excited to a feverish intensity, the Texan commanders were unable to restrain their troops; some were content to let their men have their way. “We followed the enemy,” wrote one captain, “shooting and killing them, for more than a mile.”

The rout was over, Houston wrote in his after-action report, in less than 20 minutes, but the indiscriminate killing went on for the better part of another hour. His victory complete but his wound causing him immense pain, Houston continued to issue orders for his officers to restore order, but it did little good. Houston feared that his men might use up all their ammunition and break a good number of their muskets swinging them as clubs and that they might be surprised by a column of fresh enemy troops who had found a way to reach the field. Houston was quoted in later years as stating that 100 well-disciplined Mexican soldiers could have wiped out his command after the men had broken ranks and begun wildly shooting, stabbing, and clubbing the enemy. “Gentlemen,” he told one group of rampaging Texans, “I applaud your bravery. But damn your manners.”

Counting the Dead

Once the slaughter at Peggy’s Lake was finally halted and the men had a few minutes to calm down, a wave of elation swept over the Texans as they realized what had been accomplished. The band’s drummers beat the call for assembly, bringing the various companies slowly back to camp. Sherman and his men began taking prisoners of the Mexican survivors who wanted to surrender; hundreds were quickly rounded up about the camp. About three miles from the battlefield, more than 200 Mexican soldiers came out of some woods and surrendered en masse to Rusk and a group of Texans. Houston’s report noted that 630 Mexican soldiers were killed and another 730 captured, of which 208 were wounded. Only seven Texans were killed outright; four more died of their wounds and another 30 were wounded. The Texans seized all the goods left in the enemy camp, including about $1,200 in cash, 600 muskets, 300 sabers, 200 pistols, several hundred mules and horses, and the nine-pounder cannon.

Late in the afternoon, Houston returned to camp and finally allowed his wound to be examined. Even at rest, he continued to fret over the possibility of an unexpected enemy assault. He called for Colonel Almonte, an English-speaking aide to the dictator, and asked him where Santa Anna had gone. Almonte responded truthfully that he wasn’t sure but that he had seen him riding away from the field when it became evident the battle was lost.

The Capture of Santa Anna

An observant Texan scout, Henry Karnes, had noticed a group of Mexican soldiers galloping from the field as the tide turned; he quickly called for volunteers to mount a pursuit. One soldier who answered the call was the redoubtable Deaf Smith. On April 22 their diligence was rewarded when they captured the haughty Santa Anna. He had abandoned his worn-out horse and moved on foot into the marshes in the direction of Vince’s Bridge. Exhausted, the mud-covered Mexican president spent the night of April 21 lying in reeds and grass not far from the battlefield. As he resumed his escape attempt the next morning, Santa Anna became disoriented and headed back toward the Texan camp. He found some shabby, albeit dry, clothing in a deserted slave cabin, where he was discovered and captured by Karnes and Smith. As he was being escorted into the Texan camp, the prisoner’s true identity was discovered when he was greeted with cries of “El Presidente” by other Mexican soldiers. A quick search of his clothing revealed a shirt held together with diamond studs.

Santa Anna was quickly brought before the wounded Houston, who was reclining in discomfort in the open air beneath a large tree and was in no mood for Santa Anna’s bellicosity. Encircled by vengeful Texans, Santa Anna demanded to be given the courtesy that his status as a prisoner of war required. Visibly trembling, the dictator told Houston, through an interpreter, “That man may consider himself born to no common destiny who has captured the Napoleon of the West, and it now remains for him to be generous to the vanquished.” Houston replied angrily that no such generosity had been extended to the garrisons at the Alamo and Goliad, but Santa Anna need not have worried about his fate. Houston had no plans to execute the generalissimo—Santa Anna was worth much more to Texas alive than dead. Houston and Rusk spent 90 minutes conferring with Santa Anna, during which time he promised to stop the war and send Filisola and the other troops out of Texas. Houston agreed, as a temporary solution, to a limited withdrawal of Mexican troops rather than absolute surrender or a full-scale retreat. Caro was summoned to prepare Santa Anna’s dispatch to Filisola to that effect. Santa Anna ordered Filisola, Urrea, and Gaona to march back to San Antonio and Victoria under a flag of truce, pending his own negotiations with Houston to put an end to the war.

Taking the West

In the Texan camp, Houston’s aides busied themselves with counting up the spoils of battle. One comparatively compassionate Texan, John Linn, seeing the Mexican corpses festering in the sun, suggested to Houston that several hundred heavily guarded prisoners bury their dead comrades. When Houston repeated this suggestion to Santa Anna, the dictator replied cavalierly that he was wholly indifferent to the disposition of his men’s bodies. The Mexican corpses remained on the field throughout the summer. Eventually, local ranchers finally buried the Mexican dead in a common grave, the whereabouts of which remains unknown.

On May 14, Santa Anna signed the Treaty of Velasco, in which he agreed to withdraw his troops from Texan soil and, in exchange for safe conduct back to Mexico, to lobby for recognition of the new republic. For various reasons, however, the safe passage never materialized. Santa Anna was held for six months, during which time his government disowned any agreement he might enter into, and he was finally taken to Washington, D.C. There he met President Andrew Jackson before he returned in disgrace to Mexico in early 1837. By then, Texan independence was a fait accompli, although Mexico did not officially recognize it until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican War in 1848.

For Mexico, the Battle of San Jacinto, one of the most decisive battles in the history of the Western Hemisphere, was the beginning of a downward military and political spiral that would result in the loss of nearly a million square miles of territory. For the Texans, their shockingly swift victory led to annexation by the United States and the resultant war with Mexico. In the end, the American government gained not only Texas but also New Mexico, Nevada, California, Arizona, and Utah, as well as parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Wyoming, and Colorado—almost one-third of the present-day United States. All things considered, it was not a bad day’s work for 18 minutes of battle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments