by Douglas Sterling

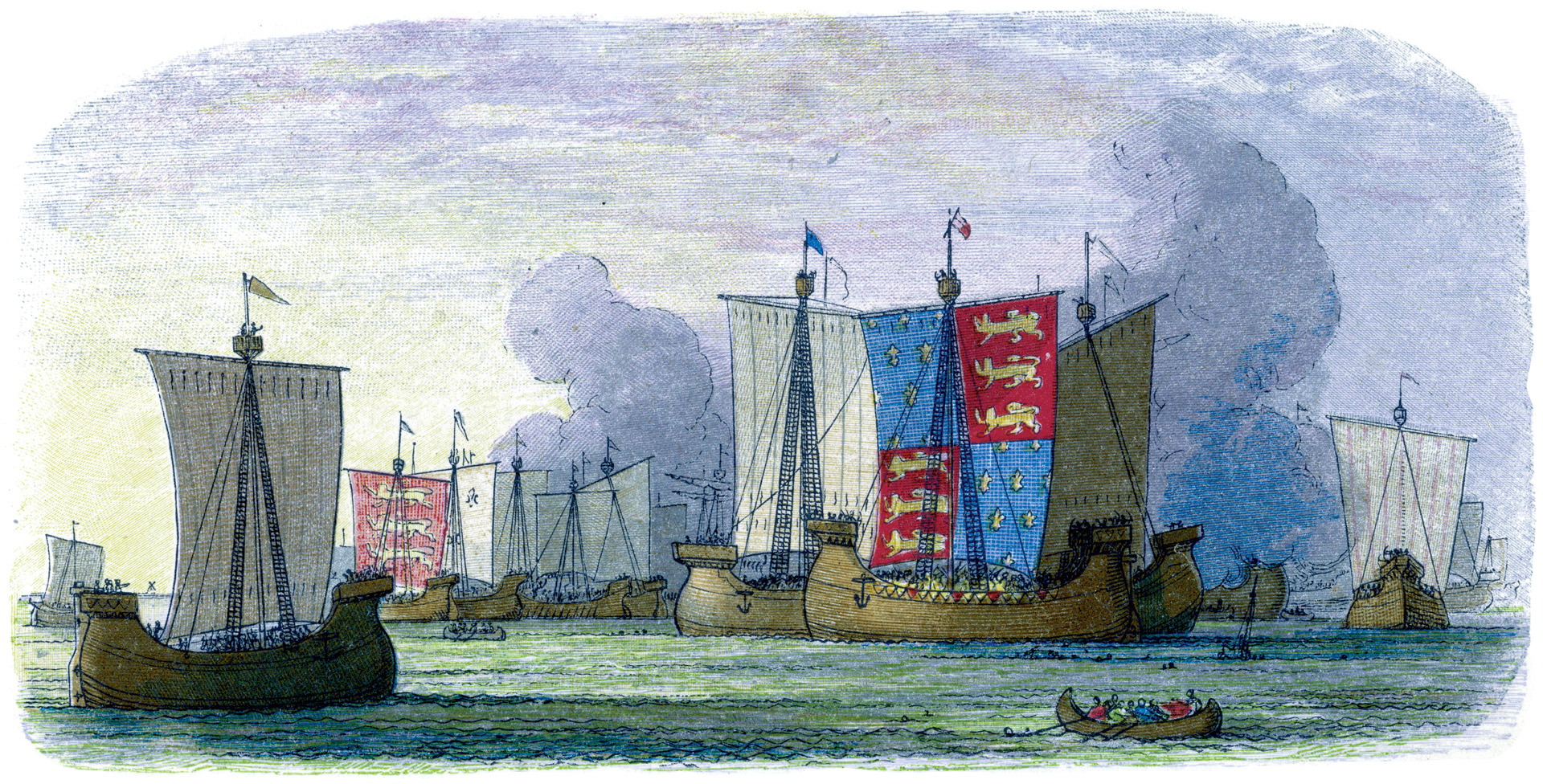

English King Edward III’s ship drew out from the fog, and before him he saw such a long, deep concentration of masts that it looked like a forest rising to meet him. Yet he knew that what he really faced was the Norman fleet. This was the very force that had done such damage to England’s merchant fleet and her coastline, most particularly in the audacious and devastating attack on the city of Southampton two years earlier. Ahead through the mist was the fleet that King Philip VI of France had kept constantly at sea since hostilities between the two countries had begun three years before in what would come to be known as the Hundred Years’ War.

Now, in June 1340, after a series of defeats, Edward was in a fighting mood. He declared to those around him that he thirsted for revenge and, “please God and St. George,” he would be able to close with his enemies that day. Edward ordered his ships drawn up in line so that there was one shipload of men at arms between every vessel with archers, with other ships full of archers held in reserve.

The Hundred Years’ War was in actuality a series of wars between England and France, waged ostensibly over the continental lands that England claimed in its territories of modern France, the manner by which they were held, and who possessed the ultimate controlling authority. The primary cause of the first phase of the war, which descended into hostilities in 1337, was the nature of the feudal relationship between the King of England as Duke of Aquitaine (also known as Guyenne) and the King of France, by whose lordship the lands were held. Problems had arisen as early as the reign of Edward III’s grandfather, Edward I (Longshanks), who resented the demand by the French that Guyenne (in southwestern France) was to be held as a liege fief, meaning that the King of England, as Duke, held the land at the pleasure of the King of France, who could revoke or amend his control upon his recognition of certain inadequacies in governance.

For the First Time in 300 Years, France had No Heir to the Throne…

Disputes, often erupting into combat, periodically arose over the English manner of governance and control of Guyenne. In 1316, Louis X of France died without a male heir. For the first time in 300 years, there was no direct male succession for the throne of France. A great council, summoned to consider the question, gave the crown to Louis’s brother Philip, who reigned as Philip V. Upon his death six years later, another brother, Charles, was crowned as Charles IV. When, in 1328, Charles himself died, also without a male heir, the subject was once again up for discussion. The question was raised whether a woman, although unable to occupy the throne herself, could nevertheless pass title to her son. If that were so, then the next heir to the throne would be Edward III of England, as the son of Isabelle, the daughter of Philip IV and sister of the last three monarchs. Isabelle, however, was not popular at the French court. Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer, had together deposed Edward II and proclaimed her son Edward III as king. Edward II soon died in captivity and was widely believed to have been murdered. Therefore, Isabella was a disreputable figure, making it easy for a subsequent council to give the throne to the Count of Valois, son of Philip IV’s brother. Of controlling influence in the council, he was thus recognized by the French as Philip VI. In this manner, the “law” was interpreted as barring female succession to the French throne.

Although Edward’s interests were thus disposed of, he (and his advisers, because he was a lad of 15 and had held the English throne for only a year) did not dispute the succession or press his claim further. Indeed, in the interests of keeping the peace between England and France and maintaining the French agreement for neutrality in the disputes between England and Scotland, Edward agreed to fulfill his duties and personally paid homage to the new King of France.

This period of amity was not to last, and Edward held his claim to the throne as a card that he may or may not have been loath to play, but would not discount if pressed. In 1330, Edward took full control of the government by having Mortimer executed and his mother confined to a convent. He won his military spurs in action by defeating the Scottish King David II at the battle of Halidon Hill. However, the French alliance with the Scots and increasing tension over Guyenne promised further trouble with France. Edward’s claim to the French throne through his mother promised to be renewed.

By 1337, the French king had pushed numerous legal measures in support of lords in Guyenne who were unhappy with judgments passed against them by the English ducal government. Edward protested and sought redress in judicial counsels in Paris, to little avail. Philip VI was determined to push the issue, and succeeded in wooing various allies and vassals of the English King to transfer their allegiance to the French. Some of Edward’s most important subjects in Guyenne, such as the Abbot of La Sauve-Majeure and the Count of Armagnac, were lured away from him by a combination of military and judicial pressure. The situation was ripe for a singular case to break the camel’s back, which is eventually what happened. Garcie Arnaud, Lord of Navailles, had been pursuing a judgment against Edward III for years, but Edward’s attorneys had always been able to stall. In July 1336, the French Parliament decided for Arnaud and awarded damages to be honored by the seizure of various assets in Gascony. Edward made the decision to defy the verdict. Philip, attempting to make good the judgment, declared Edward in default and disobedient and his lands therefore forfeit. Philip then took active military steps to confiscate the lands of the ducal government.

Debating the 100 Years War

Many who have studied the Hundred Years’ War believe that naval aspects constituted at most a peripheral part of the military aspects of the struggle. An overview of the war, its conduct, and its effects, however, shows the vital nature of naval power and its consequent ability to control and utilize shipping lanes. Control of the seaports and access to the sea—for both commercial and military purposes—was one of the causes of the war, as was France’s desire to expand. Although much of the fighting that began over control of Guyenne was necessarily land-oriented, with the French king supporting offensives up the Garonne, the main waterway into Guyenne which terminated in the major city and trading center of Bordeau, to consolidate bases. The beginning of the war also heated up an already warm conflict on the seas. And the escalation of conflict in the early part of the war led to a series of humiliating and devastating defeats and reverses for the English at sea as well as on land. Long considered by historians somewhat an aimless, relatively profitless exercise for the French, their naval war against English interests was actually quite intelligent and successful. The French, with powerful naval allies, had, if not total control of the sea lanes between England and the Continent, relatively free reign to strike at English interests, both in their Continental possessions and the maritime communities of England itself.

One reason for the relative lack of interest in the naval war among the chroniclers of the time may have been the low esteem in which sailors and those fighting at sea were held. Naval warfare was not an occupation in which the nobility was trained. Nor was the importance of it, or the results that could be attained by it, seen as clearly by contemporaries as land battles and campaigns.

Indeed, the French and their Castilian allies made the English victims of innovation stemming from the ideas of their Mediterranean commanders. Raiding and the deliberate destruction of resources lay at the heart of medieval strategy on land and at sea. The French campaign, according to N.A.M. Rodger, a historian of naval warfare, was “carefully and ruthlessly calculated … [I]n a war of attrition, victory went to the side which could waste the enemy’s economic resources while preserving his own means of making war.”

In 1338, the first full year of the war, the French naval campaign was highly effective in harming the English naval forces, destroying support systems and, most importantly, instilling fear and tying up resources in English coastal regions. In March, French galleys attacked Portsmouth and French raiders burned the town. From there, the galleys moved on to raid Jersey, one of the Channel Islands and vital protector of the English supply and trade lines to Guyenne.

The Genoese Proved Their Worth by Capturing Guernsey

The French effort was soon to be aided by 20 Genoese galleys under the command of Ayton Doria who, followed by 17 Moroccan galleys, sailed north to join the French fleet. The French also received the aid of a Castilian fleet, which attacked an English convoy in the Bay of Biscay in August, capturing two English ships.

In September, the Genoese proved their worth by capturing Guernsey, another Channel Island. They did not stop Edward III from crossing to Flanders, but were successful in cutting his lines of communication behind him. They also captured five of Edward’s ships, including the cogs Christopher and Edward, two ships that were to play a part at the Battle of Sluys two years later. (A cog was a large, flat-bottomed cargo carrier with high sides. Designed to be easily converted to military use, it was used for transporting men, horses, and supplies and for adding on built-up decks, or “castles.”)

One of the most devastating naval actions during the war, and perhaps the one with the most far-reaching consequences, was the attack by a Franco-Genoese squadron on the English seaport of Southampton on October 5. The town was captured and burned. The destruction of such a major seaport and shipping center sent a profound shock through the south of England. By the end of the year, other coastal areas had also been devastated. According to Rodger, “England was in a state of panic. No naval force existed which was capable of opposing a powerful force of galleys, and the coast defence system was useless against a fast-moving enemy.” Edward was forced to warn the coastal areas of further attacks and ask them to prepare for the worst.

In March of 1339, Carlo Grimaldi, with a force of 17 galleys, 35 Norman barges, the cog Christopher, and a force of 8,000 men made a series of assaults in the Channel. This was a large force by medieval standards, especially in association with a fleet. The English had no adequate defenses for whatever the French force planned, except to try and respond to each attack as it happened. Grimaldi attempted to capture Jersey, but failed. He did succeed, however, in reinforcing Guernsey and capturing the fortress cities of Bourg and Blaye on the Garonne River. Grimaldi’s success can be attributed to his being one component of a two-pronged attack. For, at the same time, Doria attacked Harwich, the south coast, and Bristol Channel. He entirely destroyed Hastings and took ships in Plymouth harbor, although the town repulsed a land assault.

Phillip’s Invasion of Conquest

Phillip VI was clearly contemplating an invasion of conquest, and it appeared England did not have the ability to defend against it. The situation was further exacerbated by Scottish barge attacks on English shipping to northern castles and strongholds. In July, the Scottish, with the aide of a French privateer, closed the Tay River and forced the surrender of the English garrisons of Cupar and Perth.

Eventually, the English naval organization began to come around and pull together as an effective force, at least for defense. Lord Morley, admiral of the northern fleet, achieved the first English naval success of the war. Although it ended unhappily, his action showed that the English could mount a successful operation. In April, Lord Morley sailed for Flanders with a fleet of 63 ships. On the Flanders coast, his fleet encountered an enemy convoy escorted by Genoese galleys. Chasing them into the port of Sluys, the English took many prizes, but proved themselves undisciplined and plundered neutral Flemish and Spanish ships as well, compromising Edward’s attempts at negotiating an anti-French alliance. On return to the Pool of Orwell, Morley’s fleet argued over the division of booty and part of the fleet deserted.

Marley’s remaining fleet was still a potent enough force to drive off a Franco-Genoese squadron, which attempted a raid on the Cinque Ports in southeastern England in July. It was also potent enough to support the Edward-led English expeditionary force and offensive into the Low Countries in 1339-1340. Although ultimately a failure, this offensive nevertheless had some local successes, not least because of Philip’s refusal to risk battle against an English army supported by Flemish and Imperial allies. While Philip suffered considerable criticism for this Fabian strategy, it nevertheless reflected the weaknesses of Edward’s alliance with allied contingents in various states of enthusiasm. Edward spent a lot of monetary and political capital for very little gain, but it was gain he hoped to build on in 1340. Fortunately for him, the French naval force was not able to keep him bottled up in Flanders, nor to prevent him from returning in the summer.

By this time, discontent within the French squadrons had caused a number of desertions. Doria’s men were unhappy with their lack of pay and sent representatives to Phillip VI to petition for redress. When the representatives were arrested, the squadron mutinied and sailed back to Genoa, taking two of Grimaldi’s galleys with them.

In September, the rest of the French force sailed to Sluys, intending to raid the English herring fishery off Yarmouth, but instead was dispersed by seasonal gales. By the end of 1339, Grimaldi had gone back to Morocco and the rest of the Italian galleys were taken out of service, allowing Morley to raid the French coast with near impunity.

More important, however, was the capture in early January 1340 of a French ship from Boulogne by seamen from the Cinque Ports. Four of the merchants taken prisoner revealed the existence of 18 galleys the French had beached in Boulogne harbor. Normally, the ships would have been laid up in Rouen, but they had been kept ready for use for an escort mission. On January 14, the English raided Boulogne. A fleet of small vessels attacked through a heavy mist and was not seen by the small guard until it was in the harbor. The English were able to take the lower town and burn the galleys, as well as a warehouse of naval stores and a number of merchantmen, before being expelled by the French with heavy casualties.

Edwards Struggles to Gather a Fleet

The raid on Boulogne, coupled with raids on Dieppe and Le Treport in the new year, made it unlikely that Philip could prevent either Edward’s return to England in February or a repeat invasion of Flanders. The French knew about the invasion force, of course, as they were well informed of the massive plans being put into place in the English port cities. Unable to threaten the invasion fleet in English waters, or to intercept it en route, the French fleet was nevertheless sent to Flanders to prevent an English landing and to support the French army’s invasion of the Low Countries. Philip’s design was to hinder or disable any further coalition force Edward might command.

Edward had begun preparations for assembling a fleet early in the year. At this time, the English method of gathering a fleet relied heavily on the draft of ships, men, and material from those required to give service at the king’s command. Unfortunately, the acceptance of this call to arms was dilatory at best. Often the ships promised did not even exist. But, beyond that, the king’s council was often flooded with appeals for consideration—either for delay or for limitation of a community’s requirement. It often took months for all the resources to be pulled together, months that sometimes required an expeditionary force to wait in dangerous idleness in port while all the ships were gathering.

For the 1340 expedition, Edward also made an effort to hire galleys in the Mediterranean, to offset the Castilian and Genoese contingents of the French. Applications to the Venetians, however, were fruitless. Equally disheartening was the failure of the English envoy to the Avignon papacy to hire warships from southern France, or at least to prevent Philip VI’s attempts to do the same.

Edward continued to believe that the English coast was under threat. He did not recognize the resulting shift in French plans for their naval forces from offensive operations to a mission of support for a land campaign. Consequently, early English plans to hold back some of their larger vessels from the invasion force for coastal defense continued unabated until June.

Transports for the invasion force were due to be ready by early April, but, not surprisingly, were delayed. Edward allowed for some flexibility, but by May, reports were made of French raids in Hainault, and the English were receiving urgent calls for help from their Continental allies. The fleet had been ordered to assemble at the Pool of Orwell and the Downs off Sandwich, but only the fleets of Yarmouth and the Cinque Ports had arrived by May 4; embarkation had to be postponed.

“Great Army of the Sea”

On May 16, the English royal council met and pushed back the deadline for gathering the ships until June 12, which would mean a sailing date around the 20th. When Edward met with his council again on June 4, it was clear that earlier delays had not been resolved. The only way to even attempt to keep up with the timetable previously set, which was being relied upon by the allies, was to send at least a small force across the Channel to give support. Little did the English council know that the French had amassed a fleet, principally from the Norman ports, and had sailed from Harfleur on May 26. It was a large force, consisting of 202 vessels—seven royal sailing ships, six galleys, 22 oared barges, and 167 merchantmen— requisitioned by Philip’s agents. By the time the smaller English force sailed, the French had passed Calais.

The French fleet, called the “Great Army of the Sea,” appeared off Sluys on June 8. According to Jonathan Sumption, author of a multivolume history of the Hundred Years’ War, the French soon “swiftly and brutally occupied the island of Cadzand and anchored in the mouth of the River Zwin opposite the harbor of Sluys. The news passed rapidly through the Low Countries, spreading panic in coastal towns and drawing a great crowd of gapers to the foreshore to watch the denouement.”

Reaching the English government two days later, the news of the French attacks at Sluys caused a near panic, many of the king’s advisers claiming the odds were too great to force a confrontation with such an armada. Edward’s Chancellor, Archbishop Stratford, in particular argued strenuously that the risk was too great. He had never supported the King’s enterprise and now considered it folly to risk the government’s finances, its fleet, the security of the English coast, and, indeed, the King’s person on an unworkable scheme. Edward would have none of it, and accused his advisers of trying to frighten him. For him, there could be no question of abandoning the coalition he had helped create, nor could there be any question of running from a fight. “I shall cross the sea and those who are afraid may stay at home,” he announced.

Archbishop Stratford resigned and was succeeded by his brother Robert, Bishop of Chichester. Edward was, however, persuaded to delay his departure for a few days to requisition more ships and to convert a transport armada into a battle fleet. Horses were removed to make room for infantry, and strong messages were sent to every reachable port to provide all ships over 40 tons. No excuses were accepted; Edward himself confronted the mariners of Great Yarmouth who were yet delinquent.

By June 20, nearby harbors were empty and the ships previously assembled were brought into the Pool of Orwell to join the large ships of the western Admiralty. The exact size of the armada is unclear, but is thought to have been around 140 to 150 ships when added to the Northern Fleet under Lord Robert Morley. Edward himself went aboard the cog Thomas, and the fleet set sail just after midnight on June 22, 1340.

Kind Edward Longed for Revenge

Catching a strong northwesterly breeze, the English fleet passed the point of Harwich at dawn and late on the following afternoon stood off the Flemish coast west of the Zwin estuary. Inside, the French fleet lay in wait, commanded by Admirals Hugh Quieret and Nicholas Behuchet. According to Jean Froissart, the famous chronicler of the early part of the war, “King Edward saw such a number of masts in front of him that it looked like a wood. When he asked his ship’s captain what it could be, he replied that it must be the Norman fleet that King Philip kept constantly at sea, which had done such great damage at Southampton, capturing the Christopher and killing her crew. King Edward declared that he had long wanted to fight them, and now, please God and Saint George, he would be able to, for they had done him such harm that he longed for revenge.”

The French saw the English fleet, too, and held a council of war. Barbavera, as the most experienced sailor among the commanders, counseled caution. He was concerned that the anchorage in which the French fleet lay was too confined for maneuvers if attacked and that the wind, blowing into the mouth of the river, would further hamper maneuverability. He suggested that Quieret and Behuchet take their fleets into the open ocean where they would have a better chance to maneuver and meet the English fleet on more favorable terms, but his colleagues balked. In their minds, the mass of their force was more than a match for the English. It certainly looked it, with the closeness of their ships and their great bulk, with bows, poops, and masts fortified with timber. Reinforcements from Flemish and Spanish allies brought their force to 213 vessels. Quieret and Behuchet were afraid that any move to the open ocean would provide an opening for the English force to sail in behind them and land in Flanders.

Instead of following Barbavera’s advice, the French admirals drew their ships into three lines across the mouth of the estuary, like an army on land setting up a strong defense. In the first line were 19 of their largest vessels, including the captured cog Christopher, which stood out larger than the others. Each line was chained together to form an impregnable barrier.

The English sent a knight, Reginald Cobham, ashore with two others to gather intelligence on the French anchorage and their dispositions for the battle. Their report pointed out the major weakness of the French order of battle that Barbavera had warned of: the anchored, chained, and massed lines. According to N.A.M. Rodger, “This was a traditional galley or longship tactic, serving to make the naval battlefield as much like a battlefield ashore as possible, but of course it removed any possibility of manoeuvre and resigned the initiative to the enemy.”

An English council of war decided to grasp the initiative and attack the next day when they would have the advantage of wind and tide behind them.

Preparing for Battle

At the end of the 15th century, the Zwin estuary silted up, so that the site of the Battle of Sluys is now farm land and dunes. In 1340, according to Sumption, it was “a stretch of shallow water about 3 miles wide at the entrance and penetrating some 10 miles inland towards the city of Bruges. It was enclosed on the northeastern side by the low-lying island of Cadzand and on the west by a long dyke on which a huge crowd of armed Flemings stood watching. Along the west side lay the out-harbours of Bruges, Sluys, Termuiden and Damme.”

In preparation for battle, the English also drew up their fleet in three battle lines. In the early afternoon of June 24, they began to press down from the north on the entrance to the Zwin. Although Froissart’s account of the battle is truncated in time— making it seem like the dispositions of the two fleets and the attack of the English followed quickly upon the two forces sighting one another—he nevertheless gives a stirring battle narrative. According to him, Edward deployed his fleet, maneuvering it “so that the wind was on their starboard quarter, in order to have the advantage of the sun, which had previously shown full in their faces. The Normans, unable to understand these maneuvers, thought that the English were trying to avoid giving battle; but they were delighted to see that King Edward’s standard was flown, for they were eager to fight him.” It was then that the English fleet “advanced to the sound of trumpets and other warlike instruments.”

The English had the wind and the tide. Importantly, they sailed with the sun behind them, shining into the faces of the French. Within the French force, confusion was beginning to overshadow confidence. As Sumption relates, the French fleet “had been too long at their battle stations and the chained lines of vessels, which originally extended across the breadth of the bay, had drifted eastward piling the ships up against each other on the Cadzand shore and reducing their sea room still further. The chains were useless in these conditions.” The French admirals ordered the chains to be thrown off, and the fleet then attempted to recover the open flank to the west. Unfortunately, the Riche de Leure, a front line vessel of the French force, detached from their line and became entangled with a ship of the English van. While those ships grappled and struggled together, the English front line rammed into the French.

The front lines of the two forces included their largest ships. Edward’s flagship, the cog Thomas, was among the large ships from the Cinque Ports and faced the Christopher, captured from the English in earlier action, and the St. Denis, a large vessel with 200 seamen aboard.

Sea battle tactics in this period consisted of grappling with an enemy vessel to assault the enemy decks with showers of arrows in preparation for boarding, which was seen as a kind of infantry attack, like an assault on a fortress. The idea was to hold the enemy close to weaken them for a victorious assault. This is indeed how Froissart described the beginning of the battle, with “each side opening fire with crossbows and longbows, and hand-to-hand fighting began. The soldiers used grappling irons on chains in order to come to grips with the enemy boats.” Both sides had artillery of a sort, stone throwers and giant crossbows called “springalds,” but, according to Sumption, they were “more dramatic than useful.”

Arrows Fell on French Crews “Like Hail in Winter”

Because the French force was hemmed in by the weight of the English fleet and was soon snared with hooks and grappling irons, they were forced to fight with a serious disadvantage in firepower. For, as in the English land battles that were to come in the following years, the English crews were equipped with the longbow, which was greatly superior to the crossbow used by the French and their Italian allies. As Sumption says, the longbow “was more accurate. It had a longer range. Above all it could be fired at a very rapid rate.” He quotes a London observer as describing arrows falling on the French crews “like hail in winter,” while “crossbows had to be lowered and steadied at the stirrup while the wire was strenuously levered back between every firing.”

By all accounts, the battle was ferocious and the slaughter terrible. According to Froissart, “The battle … was cruel and horrible. Sea-battles are always more terrible than those on land, for those engaged can neither retreat nor run away; they could only stand and fight to the bitter end, and show their courage and endurance.” Although the French had the advantage in numbers, the disposition of their forces and the weight at the point of attack favored the English.

Still, the French and their allies fought hard. The English forces “were hard-pressed, for they were outnumbered four to one, and their enemies were all experienced sailors. But King Edward, who was in the flower of his youth, proved himself a gallant knight, and he was supported by … many … gallant knights [who] fought so valiantly, with the help of those from the neighborhood of Bruges, that they won the day.”

The fighting proved to be fierce and lasted well into the afternoon when it became clear to the French in the rear lines that their comrades in the front were suffering grievously. Yet they were unable to join the fray because they were hemmed in between their own front line and the shore, and did not have room to maneuver round to the west. By evening, however, the English front line had broken through to the French ships in the rear and fell upon them. Now the English had a tremendous advantage in weight of ship as their cogs towered over the smaller French ships in their second line and they were able to rake the decks of the French from their greater height.

With the English clearly winning, Flemings began to pour from Sluys and other harbors in the estuary to join the fight and share in the victory. They fell upon the French from the rear as the English continued to press from the front. As night fell, the third French line of Norman merchantmen and Philip’s barges attempted to escape the estuary. The English tried to block their path and the battle devolved into a series of skirmishes as more and more French ships made toward the open sea. By 10 pm the fighting was nearly over, except for two ships so entangled that they fought fiercely throughout the night. By the time the English were able to board the French ship at dawn the next day, they discovered 400 enemy dead aboard.

Almost 18,000 Frenchmen Were Killed

In fact, only the dawn of the following day would reveal the extent of the French defeat and the tremendous loss of life and shipping. According to Sumption, the French “suffered a naval catastrophe on a scale unequalled until modern times.” The English had captured 190 of the 213 French ships that had been engaged, including their old cogs, Christopher and Edward . Although a certain number had escaped, including Barbavera’s six galleys, four of the six-oared galleys based at Dieppe, and 13 others, the death toll was almost indescribable. Again, as Sumption puts it, “The crews and troops on board the ships which did not escape were killed almost to a man. No quarter was given once a ship was boarded, and those who threw themselves into the sea, as many did, were picked up by the Flemings on the foreshore and clubbed to death.” Perhaps between 16,000 and 18,000 Frenchmen were killed. Edward himself would write to his son that each tide brought in more and more corpses.

As for the French admirals, Quieret was killed when his ship was boarded by the English. Behuchet, who was recognized by his captors, was held for ransom. Then, Edward III, in a pique of anger, waived the normal conventions of aristocratic warfare and had Behuchet hanged from the mast of his flagship.

The day after the battle, Edward, more victorious at this moment than he no doubt had thought possible two days earlier, went on a pilgrimage to the church of Our Lady of Ardembourg. After Mass, Edward made for Ghent where he was able to prevail upon the citizens there (not least due to his victory at Sluys and a fiery speech by Jacob van Artevelde, leader of the united Flemish communities rebellious to France) to have himself recognized as King of France. Flanders was now committed to Edward as their French king, renouncing Philip VI and pledging support for Edward’s military campaigns to defeat the “usurper” Philip.

In naval terms, although the defeat of the French naval forces at Sluys ended for a time the threat of a French invasion of England, the victory did little to give England any real or long-term advantage. French control of the Channel had never been complete, allowing the English to strike wherever they considered their cause ripening. Indeed, the nature of the naval war was always one of shifting advantages. The reason there were so few engagements of the decisiveness of Sluys was because, according to historian C.F. Richmond, “naval resources were seldom sufficiently concentrated to enable a decisive attempt to be made against them. And if and when they were, the problems of intelligence, communications and logistics, and the hazards of wind and weather often prevented a timely response or frustrated a response that was made.”

Sluys did not give England complete command of the sea any more than France had previously held that command. C.F. Richmond has pointed out that the very concept of “command of the sea” is an anachronism for the period of the Hundred Years’ War. Instead, naval actions actually represented “fluid situations in which the balance of initiative and fighting power shifted from one season to another.” What the English victory at Sluys achieved “was a shift in initiative and confidence: after a lean period England moved on to the offensive.”

In the short term, the victory at Sluys sent an important message to the anti-French forces in Flanders—aggressively wooed by the English king—that French interests could be flouted, and that an English alliance would be profitable. Although hindsight shows that such an alliance held little value to either side in the long run, it did eventually lead to an even greater English victory at Crécy. There, the French demonstrated that they had not learned from their mistakes at Sluys. Although they again outnumbered the English, it was the French disposition, lack of cohesion, and surrender of the initiative to the English that led to defeat.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments