By Scott A. Richardson

The Battle of Dorylaeum, fought on July 1, 1097, marked the first full-scale military clash between the Christian armies of the West and the Muslim armies of the East. As such, it would prove to be an educational experience for both armies, one whose final outcome would have an extreme influence on the course of the First Crusade.

The Origins of the First Crusade

The crusade to retake Jerusalem from the occupying Turks actually began two years earlier, with an impassioned plea by Pope Urban II in November 1095 on the behalf of Europe’s Christian brothers in the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines, as the nearest Christian targets of the rampaging and ever more powerful Seljuk Turks, had been fighting these persistent raiders for several years.

By March 1095, when Urban II held a meeting of leading European ecclesiastics, he heard from a delegation of Byzantine ambassadors that the war against the Turks was going quite well. Byzantine might had been pushing the Seljuks steadily back. The Byzantines could crush the Turks forever, the ambassadors explained to the pope, if only there were more troops for the army. They asked Urban to rally the European nobility to help save the first line of Christian defenses against the crush of Islam.

Urban did as the Byzantine mission asked—and more. Having been made aware that Christians on pilgrimage to Jerusalem were having trouble getting through Anatolia owing to Turkish harassment and were often turned away at the gates by the Muslims who controlled the city, Urban decided to launch a crusade to free Jerusalem and the entire Holy Land from Muslim domination.

Seated before a large crowd at Clermont, France, Urban decried the suffering of the Byzantine Christians, the loss of Christian territory to the Muslims, and the desecration of the holy shrines by the infidels. He then went a step further, informing listeners about the indignities and injuries suffered by pilgrims en route to Jerusalem. Once he had presented the facts, Urban launched his appeal. The Christian West, he said, should march at once to save their Eastern brethren and free Jerusalem. The French townspeople, some of whom would become the first crusaders, cheered loudly at the plan to re-take Jerusalem, calling out, “Deus le volt [God wills it]!”

“Your brethren who live in the east are in urgent need of your help, and you must hasten to give them the aid which has often been promised them,” said the pope. “The Turks and Arabs have attacked them and have conquered the territory of Romania [the Greek empire]. They have killed and captured many, and have destroyed the churches and devastated the empire. If you permit them to continue thus for awhile with impurity, the faithful of God will be much more widely attacked by them. On this account I, or rather the Lord, beseech you as Christ’s heralds to publish this everywhere and to persuade all people of whatever rank, foot soldiers and knights, poor and rich, to carry aid promptly to those Christians and to destroy that vile race from the lands of our friends. All who die by the way, whether by land or by sea, or in battle against the pagans, shall have immediate remission of sins. Let those who have been accustomed unjustly to wage private warfare against the faithful now go against the infidels and end with victory this war which should have been begun long ago.”

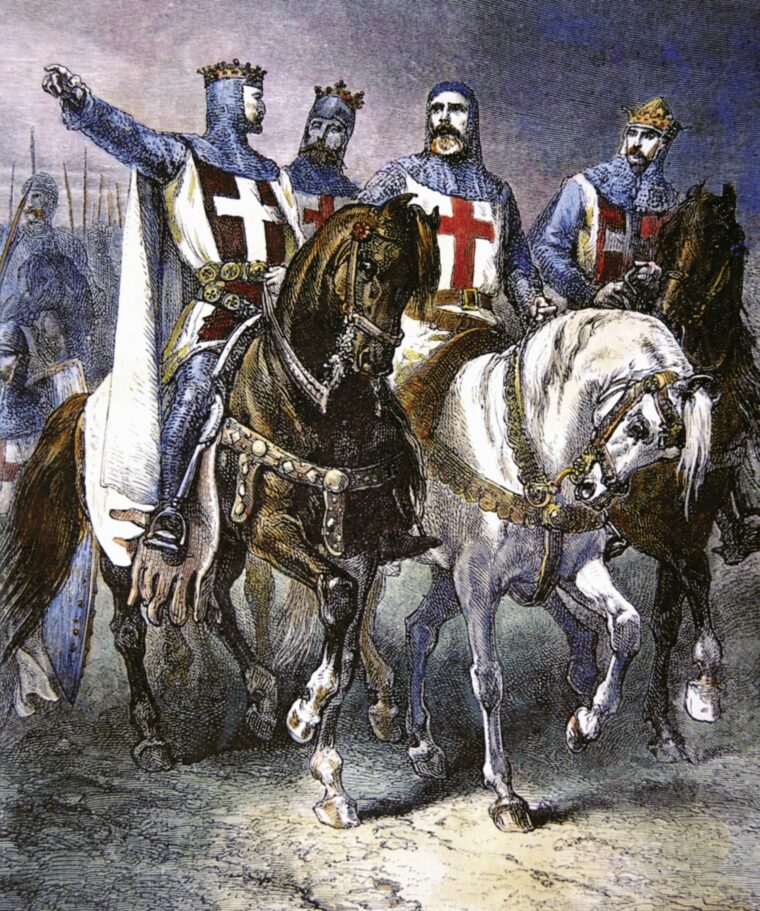

Urban toured throughout France before returning to Italy, spreading the word of his crusade and finding popular enthusiasm wherever he went. European noblemen were eager to join the crusade as well, ensuring that the war would have ample military leadership and experience. Among the leaders were Bohemond of Taranto, an Italian prince of the earlier Norman invaders; Godfrey of Bouillon, often called the perfect Christian knight; and Adhemar, bishop of Le Puy, who was present at Clermont when Urban made his appeal and was the first person there to request permission to take up the cross.

The First Crusader Coalition: Nobles and Peasants, East and West

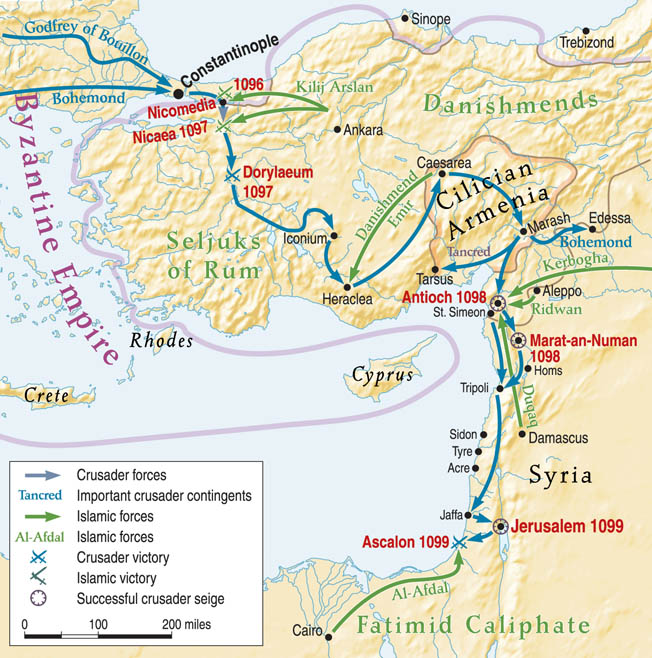

The armies of the First Crusade marched out from various places. Although this would prove to be largely a French crusade, led by French nobles and fought by French commoners, individual leaders came from all across Europe. By April 1097, the majority of the crusader armies had arrived at the convergence point predesignated by Urban II: Constantinople. While the Crusaders, or Franks, as the Greeks uniformly referred to them, regardless of their nationality, were ostensibly meeting there to defend the Byzantines, their violent behavior suggested otherwise.

An ill-led, ill-provisioned, and ill-conceived “People’s Crusade,” led by Peter the Hermit, a bizarre religious leader, had arrived in Constantinople several months before the military professionals. While there, the mob of peasants, criminals, and fanatical mystics managed to thoroughly anger and insult their Byzantine hosts before marching away. When Godfrey and the other noble leaders arrived, it took only a few weeks before clashes between East and West began, first through raids against scattered country homes to seize provisions, then in attacks against homes outside of Constantinople for the sake of destruction, and finally a limited assault on the city itself.

The two alleged Christian allies were coming to blows—and during Holy Week, no less—destroying any sense of respect or mutual trust between the crusaders and the Byzantines before the armies were ever sailed across to Asia. Nevertheless, at the request of Emperor Alexius, the Crusaders agreed to fight alongside the experienced Byzantine forces to attack the Seljuk capital of Nicaea and clear a main road running to Jerusalem. The fortress-city was formidable and well defended. It was surrounded by a four-mile-long stone wall, which was in turn studded by no less than 240 towers. The city was bordered on one side by the Ascanian Lake, with walls coming right out of the shallow water. An assault would be difficult and a siege lengthy. The attack, however, struck at just the right time. At that moment the Seljuk sultan, Kilij Arslan I, was away in the East with most of Nicaea’s garrison, fighting the Danishmend emir, Ghazi ibn Danishmend, over territorial disputes.

Nicaea Falls to the Byzantines

By June 3, 1097, the entire crusader army had arrived before Nicaea and had spread out to invest the city. Kilij Arslan, when informed of the city’s investment, at first attempted to attack the crusader lines surrounding Nicaea. The attack failed and Kilij decided to sacrifice the city in order to carry on the fight later on the open ground of Anatolia. The crusaders continued to attempt to take the city by escalade and by mining the formidable walls, but to no avail. Crusader attempts to choke off the city failed because supplies were still being ferried across the Ascanian Lake. Byzantine Emperor Alexius was asked for assistance and dispatched a flotilla to drive off the supply ships, at which time the garrison requested to parley with the Byzantine commander for a truce.

As the discussions wore on and the Turks stalled for time, garrison leaders were informed that the crusaders were planning a general assault on the city for June 19. When the sun rose that day, the crusaders were utterly shocked to see the Byzantine imperial standard flying over the city. The garrison had surrendered overnight and allowed Alexius’s forces to enter through a gate facing the lake.

The crusaders felt betrayed and angered. Not only were the nobles deprived of the glory they might earn through an attack, but they were also deprived the chance to capture and ransom Turkish nobles. The Turks instead were escorted to Constantinople under the protection of Alexius’s troops for a comfortable incarceration. The crusaders were also deprived of the chance to gather booty and vent their rage on helpless citizens, an ugly but accepted aspect of medieval warfare. The crusaders had been promised great wealth fighting for the Byzantines, yet at the first opportunity to engender goodwill, Alexius had proven stingy. This was seen as both cowardly and dishonorable, and ruined whatever sway the emperor might have held with the crusader leaders.

Dorylaeum: On the Road to Jerusalem

The acrimony at Constantinople and the betrayal at Nicaea had a tremendous impact on the upcoming Battle of Dorylaeum. No longer having any faith in Alexius or his promises for assistance, Godfrey and other crusader leaders spurned his suggestions to approach Jerusalem along the coast, thereby keeping one flank protected and allowing provisions to be delivered to the army by the Byzantine navy. Alexius’s suggestion was made in good faith, based upon years of experience fighting the Turks and knowledge of the approaching terrain, but despite the imminent logic of Alexius’s suggestions, the crusaders were no longer in a frame of mind to hear any Byzantine points of view, regardless of how intelligent they may have been. The crusaders, wanting to avoid lengthy siege operations against a series of coastal towns, chose a quicker, more direct route through the heart of Asia Minor, one that would lead them directly to Dorylaeum.

Before marching away from Nicaea on June 26, they decided to break the army into two unequal sections to ease the difficulty of supply. The weaker vanguard, under the command of Bohemond, would march out immediately, while the bulk of the army, commanded by Godfrey, would follow approximately a day’s march behind. Dividing one’s army in hostile territory is typically considered a military sin, but in this case the division would actually have an unanticipated positive effect on the battle.

Kilij Arslan had been busy following his repulse at Nicaea. He made peace with Ghazi ibn Danishmend and formed an alliance against the common Christian foe, then called upon his vassal, Hasan of Cappadocia, to provide additional forces for an attack on the crusaders. Once he had gathered his sizable and experienced force, Kilij Arslan prepared to attack at the just the right location. Learning from his scouts that the crusaders were marching on the road to Dorylaeum, the Turkish commander was waiting in an ambush for them to arrive. Kilij Arslan marshaled between 25,000 and 150,000 men for the battle—the figures vary wildly—while the crusaders had only 10,000 to 15,000 men, including knights and foot soldiers, spread out in two wings of the army.

As Bohemond’s vanguard neared Dorylaeum, he noted that his unit was being shadowed by scouts from Kilij Arslan’s forces. On the night of June 30, he chose a plain near the north bank of the river Thymbres to encamp his forces. By camping on a plain, Bohemond inadvertently chose territory perfectly suited for the fleet-footed cavalry tactics of his enemy, but being near the river also meant that his left flank and rear were protected by the marshy ground.

Bohemond’s Improvised Defenses

At dawn on July 1, the Turks attacked the camp, taking Bohemond and his forces somewhat off guard. The Turks mainly utilized fast, lightly armed horse archers, who would ride around the enemy, shooting arrow after arrow into their midst, then fall back as fresh horse archers took over the attack. If the enemy attempted to counterattack, the horse archers would simply flee, usually drawing forces away from the main body so that they could be pounced upon and decimated. To stand and absorb the missile attack was to die a slow bloody death, while attacking the archers directly proved frustratingly difficult. The horse archers were as annoying as the swarms of flies hounding the crusaders, and a good deal more dangerous.

Bohemond ordered the many noncombatants collected and secured in the center of camp, protected by a line of soldiers. Meanwhile, his forces reacted as European knights of the highest rank were expected to behave—aggressively. They quickly mounted their steeds and attacked the horse archers, with predictable outcomes. The archers would simply flee, easily staying out of reach of the knights’ heavy chargers, or else turn to attack individual knights.

Bohemond could clearly see that this tactic was not working. Like all good commanders, he improvised. He ordered his knights to dismount and join the foot soldiers to form a defensive line around the camp. At the same time, he sent out messengers to the main army with pleas to come up as quickly as possible. His goal, as he informed his captains, was to protect the camp, hold out against the Turks as long as possible, and suffer as few casualties as possible until relief arrived. His knights largely listened, although one highly impetuous one disobeyed orders and rode out with 40 fellow knights, only to receive a serious trouncing. He returned shamefacedly to camp, having lost most of his men, suffered many fresh wounds, and also gained a concomitant amount of humility.

“Rain or Hail Never Darkened the Sky So Much”

The first phase of the battle proved to be exceedingly harrowing for the crusaders. Not only was it against the knights’ nature and training to stand by passively and allow lightly armored foes to pepper them with arrows, but standing fully armored in the hot July sun, as their thirst grew greater and greater, proved to be a serious ordeal. The knights were not the only ones to suffer through the nightmare of the Turkish attack. While the arrows were having little effect on the armored knights, they were taking their toll on the noncombatants and horses, while the sheer volume of missiles being flung at the crusaders meant that chinks in their armor would eventually be found. Some 2,000 crusaders died at Dorylaeum from arrow wounds.

After several hours of suffering under the barrage, the crusaders believed they would all die there, and they prepared to stand firm until the end. Surrounded by hostile forces from which there was no escape, they could neither fall back nor attack. They were surrounded by a force that, in their minds, was the very personification of evil on Earth, being attacked in a manner to which they were not accustomed. Battle chronicler William of Tyre expresses clearly that sense of inescapable doom: “The Turks surrounded our men and shot such a great number of arrows that rain or hail never darkened the sky so much, and many of our men and horses were injured. When the first band of Turks had emptied their quivers and shot all their arrows, they withdrew and a second band immediately came from behind where there were yet more Turks. The Turks, seeing our men and horses were severely wounded and in great difficulties, hung their bows instantly on their left arms under their armpits and immediately fell upon them in a very cruel fashion with maces and swords.” Fulcher of Chartres, meanwhile, describes the noncombatants as being “huddled together like sheep … trembling and frightened, surrounded on all sides by enemies.”

Although things were not going well for the crusaders, Bohemond’s choice of campsite served him well. The Turks were unable to entirely surround the crusaders and attack from all sides at once. Meanwhile, owing to the river to the rear and the marshy ground to the left, the Turks were unable to launch an all-out charge against the crusaders’ vulnerable position, and instead could only keep up the harassing missile attack. Thanks to the favorable topography, Bohemond was able to maintain his position until noon, when, after several hours of suffering the pummeling, the nightmare ended as fresh crusader units began to arrive on the scene.

Reinforcements Arrive

First to arrive were Godfrey of Bouillon and Hugh of Vermandois, leading a combined force of 50 knights that cut through the Turks to join their besieged comrades. Their arrival had an electric effect on the field. Not only did it energize and relieve the crusaders, it totally took the Turks off guard, and they fell back after the new Christian detachment joined the fight.

The fact that the army was split began to pay dividends. Kilij Arslan assumed that his scouts had been following the entire crusader army and believed that he had all of his enemy’s forces trapped against the river. He likely assumed that he had the luxury of taking his time with a slow but steady attrition against them, while the crusaders were clearly in no position to fall back or attack. When Godfrey and Hugh arrived on the field and hacked their way through the Turks, he learned how wrong he was.

The fresh crusaders dismounted, bolstering and extending Bohemond’s position. They continued to fight defensively and desperately, yet with the increased numbers they were also attacking their foe more often and with better results. The Turks had become more aggressive as well after the arrival of reinforcements, and were staying within range long enough for the crusaders to make several small successful attacks.

The fighting was still desperate when Raymond of Toulouse arrived with the bulk of the army. These forces slammed into the Turks’ flank and pushed them back before joining the main crusader line. Once they did so, Kilij Arslan was presented with an intimidating foe. Strung out before him was the flower of European nobility and the finest military units the continent could muster. With Bohemond’s original position marking the left flank, the crusaders deployed with Bohemond’s nephew, Tancred, Robert of Normandy, and Stephen of Blois also on the left; Raymond and Robert of Flanders in the center; and Godfrey and Hugh on the right. The allied forces of the Byzantines were also in there somewhere, although Crusade chroniclers, because of pure chauvinism, do not mention them.

The Turkish Camp Burns

With the majority of the army on line, the crusader commanders decided to take the battle to their enemy, who were nearly exhausted and low on arrows after fighting without rest for close to seven hours. The crusader line rushed forward, yelling, “Hodie omnes divites si Deo placet effecti eritis [Today, if it pleases God ,you will all become rich]!” The Turks, caught off guard by the ferocity of the attack, fell back, but soon rallied and pressed the crusader line. The battle was devolving into a slugfest between two determined foes.

It likely would have remained so, eventually ending in a victory for the Turks because of their sheer numbers, if not for one unknown factor: another part of the crusader army, commanded by Adhemar of Le Puy, had not yet arrived on the battlefield. As the main body of the crusaders attacked along the Turk line, Adhemar led his detachment around the rear of the crusaders’ position and crossed the river, shielding his movement by choosing a path that put hills between him and the Turks. Once across, he fell with utter ferocity on the Turkish camp, burning and destroying everything he could. The Turks, seeing their camp burning and their possessions being looted and coming under attack from the rear as well as from the front, broke and ran, fleeing from the field as quickly as their blown horses could carry them. The Battle of Dorylaeum was over.

After the battle it was discovered that Kilij Arslan had the bulk of his treasure with him in camp, all of which fell into the hands of the crusaders. They were able to plunder the wealth of their enemy and reassure themselves that God was indeed pleased for them that day. The Turks’ gold was divided among the crusader nobles and knights, who then distributed a considerably smaller amount among their followers.

The First of Many Crusades

Dorylaeum was of major importance to the course of the First Crusade. There, Kilij Arslan had the chance to utterly stop the crusaders, perhaps forever. If he could have overrun Bohemond’s position, then attacked and destroyed Godfrey’s bulk of the army, the First Crusade would likely be remembered as nothing more than a slight incursion by European forces into Asia Minor. Had the finest nobles of France been killed, held for ransom, or sold into slavery, it would have taken very hearty Christian soldiers to make another attempt. The Crusades may well have been a nonevent had Dorylaeum ended differently.

Instead, when news of the spectacular victory reached Europe, support for the Crusade swelled, with ever more people pledging to take up the cross. Not only were people encouraged because the war was already proving to be a military success, with the chance for otherwise destitute peasants in Europe to plunder a sultan’s treasure, but the Europeans truly believed that God was their guide and such victories were a statement of divine will. In their minds at least, the final victory at Jerusalem was a foregone conclusion.

Learning the Enemy’s Ways of War

Dorylaeum was a primer for both armies. Prior to Dorylaeum, Turks and Europeans had never fought in open combat (save for limited fighting at Nicaea), so the tactics, equipment, and character of the other’s forces were unknown. Kilij Arslan, who earlier had slaughtered the poorly led People’s Crusade, most likely assumed that all European forces could be decimated so easily. After Dorylaeum, he knew better, as his own words suggest. “When [Europeans] draw close to their adversaries they charge with great force like lions which, spurred on by hunger, thirst for blood,” he recalled. “Then they shout and grind their teeth and fill the air with their cries. And they spare no one.”

The crusaders, meanwhile, had learned the hard way that lightly armed horse archers could destroy even the haughtiest and best-equipped knight in Europe. Although it would take time for the knights to put aside their almost pathological urge to charge every foe before them, they would eventually learn how to handle these forces. By the time Richard the Lionheart and Saladin clashed during the Third Crusade, the two armies had perfected ways to fight each other. Future battles between the Christians and Muslims would prove to be highly technical, well planned and executed, resulting in bloody stalemates caused by the equality of the forces involved. All of this was a direct result of the Battle of Dorylaeum.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments