By Eric Niderost

It was late November, 1812, and the fate of Napoleon’s Grande Armee hung in the balance. Several Russian armies were closing in, but if the French crossed the 300-foot-wide Berezina River, the bedraggled survivors of a once great army might still manage to escape the trap. Two bridges had been hastily thrown across the river, a frigid waterway littered with great chunks of floating ice.

Temperatures continued to plummet, until they reached -27.4 degrees Fahrenheit, or -33C. The ragged soldiers had been reduced to gaunt scarecrows from lack of food, their breath misting into clouds of ice crystals as they trudged painfully along on frostbitten feet. Some even were snow blind, and without a companion to assist them, they were doomed.

Dreams of glory were replaced by an animal instinct for personal survival. Camaraderie, even basic human compassion and decency, was all but forgotten in the struggle to keep alive. Some charged money for a place at their campfire, and teamsters callously drove wagons over wretches who couldn’t get out of the way in time. Things got worse when Russian cannonballs began to fall near the bridges, sparking fear that soon became a full-blown panic.

A traffic jam blocked parts of the spans, and in the scramble to cross many were trampled or fell into the icy waters. But amidst the chaos a voice could be heard above the groans, shouts, and cries of anguish. “Monsieur Larrey! Monsieur Larrey! Save him who saved us!” The single voice was joined by another, and another, until it was a rising chorus. Larrey, Surgeon-in Chief to Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, needed to cross the Berezina—if he didn’t, he would probably be killed by rampaging Cossacks or vengeful Russians.

Strong hands lifted him and passed him from one to another, like a piece of driftwood floating on a sea of humanity, until he was across the bridge and safely on the opposite bank. Larrey was surprised by the men’s reaction, not realizing that his selfless devotion to wounded soldiers had already become the stuff of legend. He had saved many lives in his career and the soldiers were going to return the favor by saving him.

Dominique Jean Larrey was born on July 8, 1766, in the tiny village of Beaudean, a hamlet nestled on the French side of the Pyrenees mountains, not far from the Franco-Spanish border. The son of a shoemaker, the future surgeon had humble, even obscure origins. He might have followed in his father’s footsteps, toiling away at a cobbler’s bench, but fate decreed otherwise. Orphaned at 13, he was sent to live with his uncle Alexis, who was the chief surgeon in Toulouse.

Young Larrey found he liked the medical profession, and after serving an eight-year apprenticeship with his uncle he journeyed to Paris to study under Pierre-Joseph Desault, who was the chief surgeon at the Hotel-Dieu. His uncle Andre gave him a letter of introduction, but money was scarce, and Larrey walked all the way from Toulouse to Paris, a distance of roughly 400 miles. Desault was kind, but essentially told the young surgeon he needed more practical experience.

Larrey took the advice and joined the French Royal Navy of Louis XVI, but found in the end a life at sea had little appeal. Quitting the navy, he took a position as an assistant surgeon at the Hotel-Dieu where his mentor Desault welcomed his arrival. Larrey became a passionate supporter of the French Revolution, and personally witnessed the celebrated fall of the Bastille on July 14, 1789. When the War of the First Coalition broke out in 1792, Larrey joined the French Army of the Rhine. He was an army surgeon during the 1790s, but as he gained experience he also developed new ideas in treating battlefield casualties.

In retrospect it is amazing he accomplished as much as he did, given the abysmal state of medical knowledge at the time. In 1800 the first true anesthetics were over 40 years into the future, and if a soldier was in agony he might be given a swig of liquor. But most of all Larrey and his contemporaries had no idea what caused disease or the horrible infections like gangrene that all too often plagued the wounded. The existence of pathogenic microorganisms—germs—were still unknown.

In the 1790s Larrey was appalled by the haphazard way the wounded were evacuated from the battlefield. Ambulances were posted well behind the lines, and often wounded were not picked up until the fighting was over. Many could lie on the battlefield for hours, even a day or two, suffering not only from their wounds but from shock, hunger, dehydration, and the risk of being stripped and murdered by nearby villagers or even other soldiers, especially if they were from the opposing army.

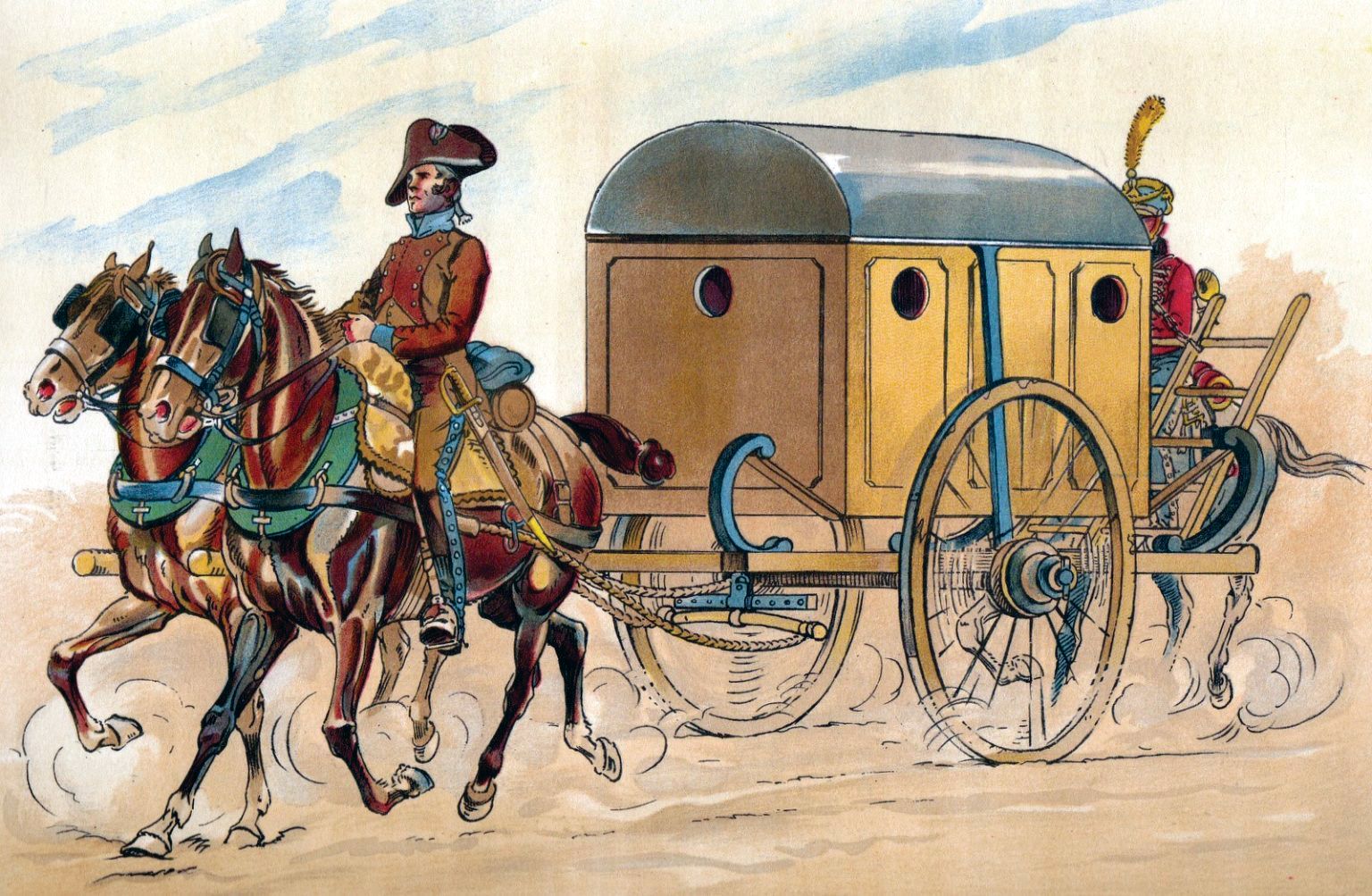

All too often these unfortunates died before they were picked up, or died en route to the dressing station. Larrey felt there had to be a better way. He was inspired by observing how fast the French mobile artillery could maneuver, and decided to create ambulances that were similar in design. The result was the celebrated ambulance volantes or “flying ambulances.”

The flying ambulances were light, wooden horse drawn carriages that were designed to carry two wounded soldiers. These ambulances could pick up the wounded even as a battle still raged, and take him to a larger vehicle for transport to field hospitals that were set up in the rear. The drivers and medical staff that accompanied each ambulance were well trained, and the carriages included portable surgical instruments, field dressings, and some medicines. Nothing was left to chance.

Larrey also developed the system of triage, which he described as “the assignment of degrees of urgency to wounds or illnesses to decide the order of treatment of a large number of patients or casualties.” Injured soldiers were divided into three groups: dangerously wounded, less dangerously wounded, and slightly wounded. The ones who had the worst wounds were given priority for treatment. Larrey’s triage system was strictly egalitarian, with no consideration given to rank, or even if a wounded soldier was from the enemy. All were treated with the best care then available.

No doubt hearing of Larrey’s reputation, General Napoleon Bonaparte requested that the surgeon be attached to the Army of Italy in 1797. It was the beginning of a long association that would last for many campaigns until the curtain fell at Waterloo. It was during the late 1790s that Larrey fine-tuned his flying ambulance system. He insisted that, when practicable, the ambulances pick up the wounded immediately, even during battle and some risk was involved. As a result almost all badly wounded soldiers had operations within 24 hours, and death rates fell.

In 1798 Larrey was appointed Surgeon in Chief of the Army of the Orient, Napoleon’s ultimately ill-fated expedition to Egypt. After the famed Battle of the Pyramids, wounded Mamluks were astonished that they were treated with humanity, decency and respect. After Larrey dressed his gunshot wound, a Mamluk Bey (chieftain) expressed his gratitude by giving the surgeon a large ruby ring. Larrey kept it with him as a kind of good luck talisman until some Prussians stole it after Waterloo.

When Napoleon prepared to secretly leave Egypt, Larrey was one of those chosen to accompany him. The surgeon politely refused, declaring the soldiers in Egypt needed him more than Bonaparte did. Larrey was repatriated to France in 1801 with the remnants of the Army of the Orient. By that time Napoleon was First Consul and ruler of France, and once he returned to Gallic shores Larrey was made Surgeon in Chief to the Consular Guard. A few years later, he was named a Baron of the Empire.

When Napoleon became emperor, Larrey was named Surgeon in Chief of the Imperial Guard, and an officer of the Legion of Honor. Once a staunch Republican, Larrey fell under Napoleon’s spell and over time became a staunch Bonapartist. He had remarkable prescience when he wrote to his wife in Egypt, saying in part “all that are united to him [Napoleon] are bound to follow. I share his career, though where it will take me or what its limits or perils I have no way of knowing.”

The years went by, and Larrey added to his laurels in campaign after campaign. He distinguished himself at the Battle of Eylau. Though the French army didn’t know it at the time, it was a small foretaste of the frozen horrors they would endure on the Russian campaign. At one point the Russians nearly overran the field hospital where Larrey was busy performing operations. Larrey refused to leave, declaring he’d die with his wounded if need be. Only an eleventh hour French counterattack stopped the Russian drive.

Such sangfroid in the face of mortal danger was typical of Larrey. During the siege of Acre, a bullet hit General Arrighi Casanova in the throat, tearing an artery. As copious amounts of blood pumped from the wound, a quick-thinking soldier literally plugged the hole with his finger. Larrey arrived on the scene and went to work immediately, though shot and shell still fell all around them. The surgeon saved Cassanova’s life, and it was only after the wound was sewn and dressed that Larrey realized his own hat had been shot off.

Larrey was present during Napoleon’s Spanish campaign in 1808, and was also on hand during the 1809 fighting in Austria. It was during the Battle of Aspern-Essling that Jean Lannes, one of Napoleon’s Marshals and one of Larrey’s closest friends, was badly wounded. A cannonball had smashed into his legs, mangling one of them so badly he could not stand. The Marshal was taken to Larrey, who saw that the left knee was shattered and there was a terrible bloody gash on the right thigh.

Normally Larrey was in control of his emotions, but the sight of his friend momentarily unnerved him. He summoned other surgeons for their opinions. It was decided that the left leg should be amputated, and Larrey, his customary calm restored, performed the operation. The leg was taken off in two minutes, then the marshal was transported to Lobau Island, in the middle of the Danube.

Lannes was at Lobau when a grief-stricken Napoleon came to visit. There seemed to be a genuine friendship between the two men—only Lannes could use du, the informal French “you,” when speaking to the Emperor. As Napoleon embraced Lannes, he soaked his white waistcoat in the marshal’s blood. Afterwards, Lannes admitted that he felt he was probably going to die, but said to Larrey, “If I am to live, only you alone can save me.”

Unfortunately six days after his amputation Lannes developed septicemia—a bacterial infection—which probably led to sepsis, an infection which spreads throughout the body. The marshal developed a high fever, and died. Hidden bacteria had triumphed over Larrey’s skills, but his triage system and flying ambulances proved their worth and saved lives.

Larrey also performed wonders on the Russian campaign. The Battle of Borodino was one of the bloodiest battles of the 19th century, and it was said that Larrey personally performed 200 amputations during the course of the day with little rest. He might have died during the terrible retreat from Moscow had it not been for the efforts of the common soldiers.

Larrey never wavered in his devotion to the wounded, and his loyalty to the Emperor. The surgeon continued to serve in 1813 and 1814, even as Allied armies closed in for the kill. When Napoleon abdicated in April, 1814, Larrey must have thought his days on active service were over forever. By then Larrey was universally respected, and even the restored Bourbons treated him well.

Nevertheless, when Napoleon returned from exile to begin the celebrated “100 days,” Larrey had no qualms about rejoining his beloved Emperor. When Napoleon’s attempt to reestablish himself on the French throne ended with his defeat at Waterloo, Larrey came within a hair’s breadth of being executed by the Prussians in the aftermath of the French defeat.

Larrey tried to get his ambulances to safety, but they were blocked by Prussian lancers. Firing his pistols, Larrey went forward at the gallop to try and force a passage for the ambulances. In the confusion, Larrey’s horse was killed and he received cuts—either from a sword or lance—on his head and shoulder. Falling to the ground, he lapsed into unconsciousness.

The surgeon was captured by the Prussians, and stripped of almost everything he had, including most of his clothes. Disheveled, barefoot, and bleeding profusely from the head wound, Larrey was in a bad way. No one knew who he was and orders were given to shoot him—he was a Frenchman, and the Prussians were out for revenge. A Prussian surgeon bandaged his head wound, but he was still earmarked to be summarily executed.

At the last minute he was recognized, spared, and sent on to General Friedrich Wilhelm von Bulow, who treated him kindly, gave him clothing, and sent him on to Field Marshal Blucher. Once again, Larrey’s past good deeds had a role in saving his life—years earlier he had saved the life of Blucher’s son.

Like many Bonapartists, Larrey was out of favor when the Bourbons returned in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. But after a few years, past political associations were forgotten, and Larrey not only had his pension restored, but was appointed a member of the distinguished Academy of Medicine that was established in 1820. He remained active, lecturing and performing duties as Surgeon-in-Chief of Les Invalides in Paris, the celebrated old soldier’s home. He died in 1842, honored by all.

Dominique Jean Larrey is considered by many historians to be the first modern surgeon. The basic principles he laid down in the treat of wounded, like triage, are still practiced today. Napoleon remembered Larrey in his will, and once said that the surgeon was “the most virtuous man I ever knew.”

An amazing and compassionate man, saving lives in the middle of mayhem.