By Eric Hammel

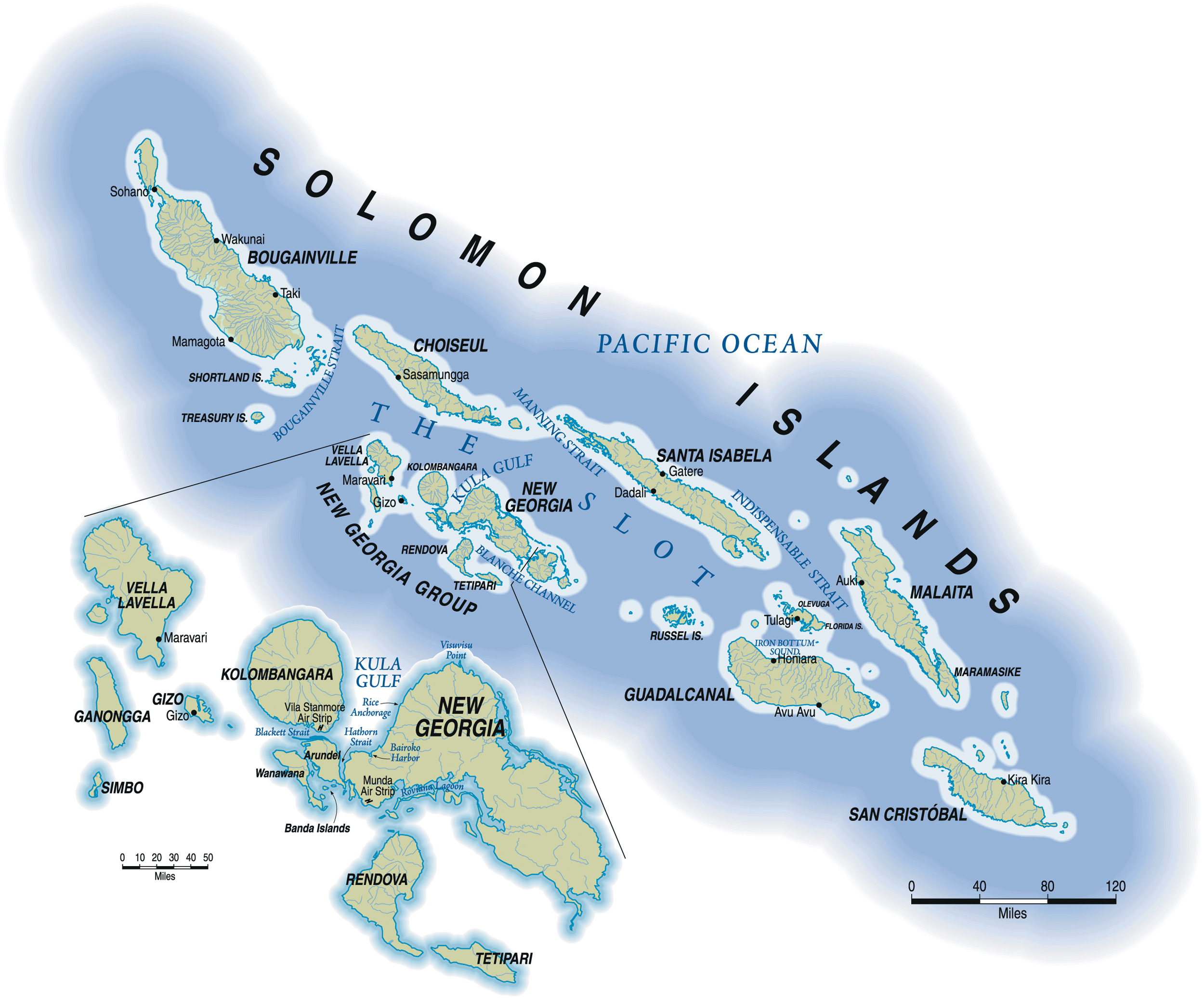

The Allied invasion of New Georgia began on June 30, 1943, when a large part of the U.S. Army’s 43rd Infantry Division landed at Rendova Island. This landing was a first step toward the capture of the strategically important Japanese air base at Munda across a narrow stretch of water from Rendova Island.

During the night of July 4, as the 43rd Infantry Division’s main drive against Munda got under way, a force of U.S. Marine Raiders and two U.S. Army infantry battalions from the 37th Infantry Division were landed at Rice Anchorage in northwestern New Georgia. It was the goal of this force to divert Japanese troops from the main battle before Munda, and to block the flow of Japanese reinforcements to Munda via Kolombangara Island and New Georgia’s Bairoko Harbor. In order to divert attention from the landings of Marine Colonel Harry Liversedge’s Northern Landing Group at Rice Anchorage, a strong force of U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers gathered to make what they hoped would be a devastating bombardment of the Japanese installations around Vila Stanmore on Kolombangara.

Quite by chance, the Japanese themselves had reached a decision to begin moving ground troops from their northern bases to Kolombangara aboard fast destroyer-transports. From Kolombangara, the ground troops would be moved to Bairoko by landing barges. The first destroyer-borne reinforcement effort was set to go off on the night of July 4, when 4,000 Imperial Army troops were to be set down at Vila for eventual staging into the Munda defense complex via Bairoko.

On the American side, Rear Adm. Walden L. “Pug” Ainsworth’s Task Group 36.1 was just getting into position in Kula Gulf a bit before midnight. Once in the gulf, Ainsworth’s force set a direct course for Vila, leaving the U.S. Navy destroyer-transports carrying the Northern Landing Group troops to make their own way to Rice Anchorage. As the bombardment force left the destroyer-transports behind, the destroyers Strong and Nicholas pulled ahead of the main battle force to check for surface or submarine intrusions with their late-model radar and sonar gear.

The night was dark and overcast. A moderate southeastern breeze was pushing intermittent rain squalls out over the gulf area.

At 12:26 am on July 5, the light cruisers Helena, Honolulu, and St. Louis (composing Cruiser Division 9) began firing on preselected targets with some 3,000 6-inch rounds. The destroyers O’Bannon and Chevelier added to the bombardment with their 5-inch guns. The job was completed in relatively short order and the formation stood out to the east. Soon the U.S. Navy vessels opened fire against Bairoko Harbor.

In the meantime, the U.S. Navy destroyer-transports carrying the Northern Landing Group followed the northern shore of New Georgia toward the Rice Anchorage landing site. At 12:31, the Ralph Talbot’s radar picked up two forms standing out of Kula Gulf at 25 knots in a north-northwesterly direction.

A few minutes later, the destroyer Nicholas, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Andrew J. Hill, was moving northward after completion of the Bairoko bombardment. The remainder of Admiral Ainsworth’s bombardment force was following in column formation.

At 12:49, just as Ainsworth was querying the Ralph Talbot about the reported radar sightings, Lieutenant James A. Curren, the Strong’s gunnery officer, spotted a torpedo wake bearing down on his ship. Before Curren could sound any sort of alarm, the Strong’s hull was torn open on both sides by the terrible impact of the exploding warhead. The forward fireroom was demolished, and the engineering spaces were flooding. The Strong turned over to starboard and sagged amidships. As she staggered forward to a forced halt, the remainder of Ainsworth’s column ran swiftly past lest they, too, fall prey to some unseen enemy.

The torpedo that stopped the Strong had been fired by a Japanese destroyer-transport, part of a group many miles to the northwest of the American force. The Japanese had been inadvertently warned of Ainsworth’s presence as the first American salvos were being unleashed against Vila Stanmore. In an effort to avoid a direct encounter, the Japanese had fired a wide spread of their superb, lethal 24-inch Long Lance torpedoes in hopes of scoring a hit on something of value. The torpedo that had taken out the Strong had done so by pure chance.

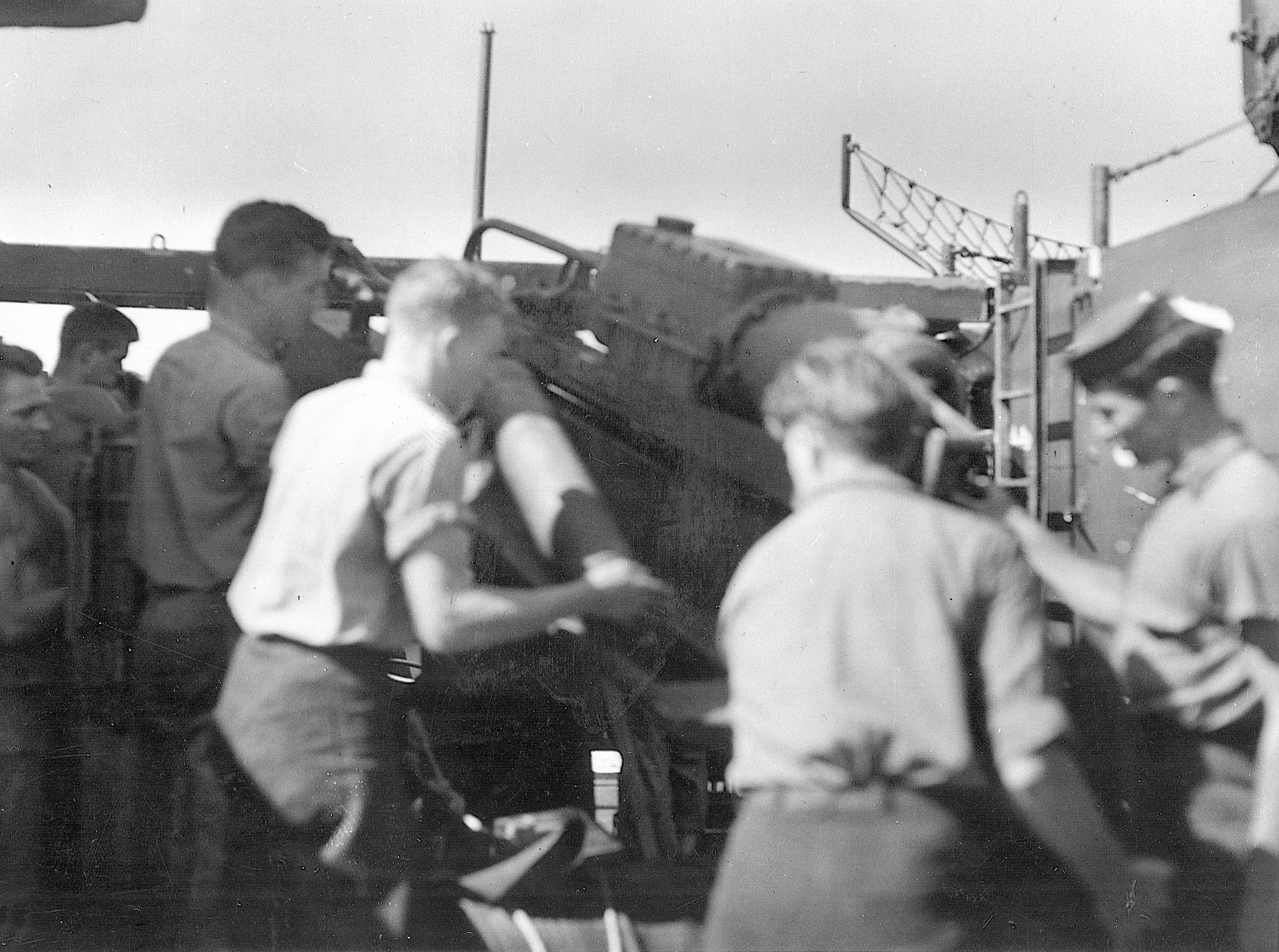

Admiral Ainsworth attempted to raise the Strong’s captain by radio, but the effort failed, so the task force commander dispatched the destroyers O’Bannon and Chevelier to undertake rescue operations. By then, the Strong had drifted to within two miles west of Rice Anchorage. Her captain, Commander Joseph H. Wellings, decided to keep all hands aboard the ship in the hope of facilitating rescue operations in the event assistance arrived in time. The Chevelier, which reached the Strong first, charged right in and buried her bows deep into the Strong’s port side. Lines were passed between the ships and cargo nets were rigged out. Sailors from the Strong began swimming to safety.

Suddenly, just as the rescue operation began in earnest, a Japanese shore battery composed of four 14cm naval rifles opened on the drifting targets. The guns, which were emplaced at Enogai village, were soon supported by lighter batteries that opened fire from positions around Bairoko Harbor. A Japanese float spotter plane arrived over the area to drop parachute flares to assist the gunners.

When one shell—a dud—plowed into the Strong, the O’Bannon immediately pumped 5-inch shells back at the Japanese shore batteries. In the meantime, the Chevelier took off the last of the Strong’s 241 crewmen and backed down from the remains at 1:22 am. Only a minute later, the Strong sank from view, and her starboard depth charges went off in a final, brutal protest.

As the O’Bannon and Chevelier made for the nearest exit from Kula Gulf, their radios sparked out simultaneous messages for all American ships to remain on the lookout for Strong survivors who might have stepped off the ship before her demise and who might have been severely hurt from concussion given off by the depth charges. Other ships did, in fact, pick up several members of the Strong’s crew, including Commander Wellings, but 46 sailors were lost.

During the operation centered around the Strong, the entire Northern Landing Group was safely deposited at Rice Anchorage. And so all the American warships retired.

During the afternoon of July 5, as he was leading his ships back to the Allied advance naval base at Tulagi, Admiral Ainsworth received a message from Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, the South Pacific Area commander. A force of Japanese warships was reportedly getting up steam at Buin preparatory to sallying into Kula Gulf that night. Upon reading Halsey’s message, Ainsworth, who was among a new breed of aggressive U.S. Navy task force commanders sent to the South Pacific following the Guadalcanal campaign, ordered his ships to turn about and steam at an eager 29 knots.

The Chevelier, whose bows had been ripped up during the night’s rescue operation, was ordered to dock at Tulagi. There she passed her supply of ammunition to the destroyer Radford, which would take her place in Ainsworth’s column. The Radford finished topping off her magazines and fuel tanks at 4:47 pm and rushed to rendezvous with Ainsworth’s speeding column. After passing up an offer to load an extra two hundred 5-inch shells, the destroyer Jenkins also rushed to catch up with Ainsworth’s force. She had been ordered to replace the Strong.

There was no time for anything resembling a command conference. Both the Nicholas and O’Bannon were operating on marginal fuel supplies; neither had any oil to waste. Orders had been summarily passed from Admiral Ainsworth, and there were two destroyers that joined the group late whose captains and crews did not know what Admiral Ainsworth wanted them to do if Japanese warships were encountered. Nevertheless, the Radford and Jenkins had sailed under Ainsworth at one time or another in the past, which minimized the chance that they might stray far from the prescribed track. On the plus side, every ship in the task force was equipped with modern surface-search radar, and each was fitted with a Combat Information Center (CIC)—an innovation—from which the action could be monitored and controlled.

Ainsworth’s plan envisaged two possibilities: Task Group 36.1 could carry out a medium-range engagement at between 8,000 and 10,000 yards with full radar-controlled gunfire, or a long-range engagement making use of star shells for illumination. The admiral felt that any radar the Japanese might have would be the usual crude variety. Also, he knew that the Japanese would prefer to launch a torpedo assault from a long range. Ainsworth assumed, however, that his three 6-inch cruiser batteries—totaling 45 radar-controlled guns—would be the determining factor in the upcoming battle.

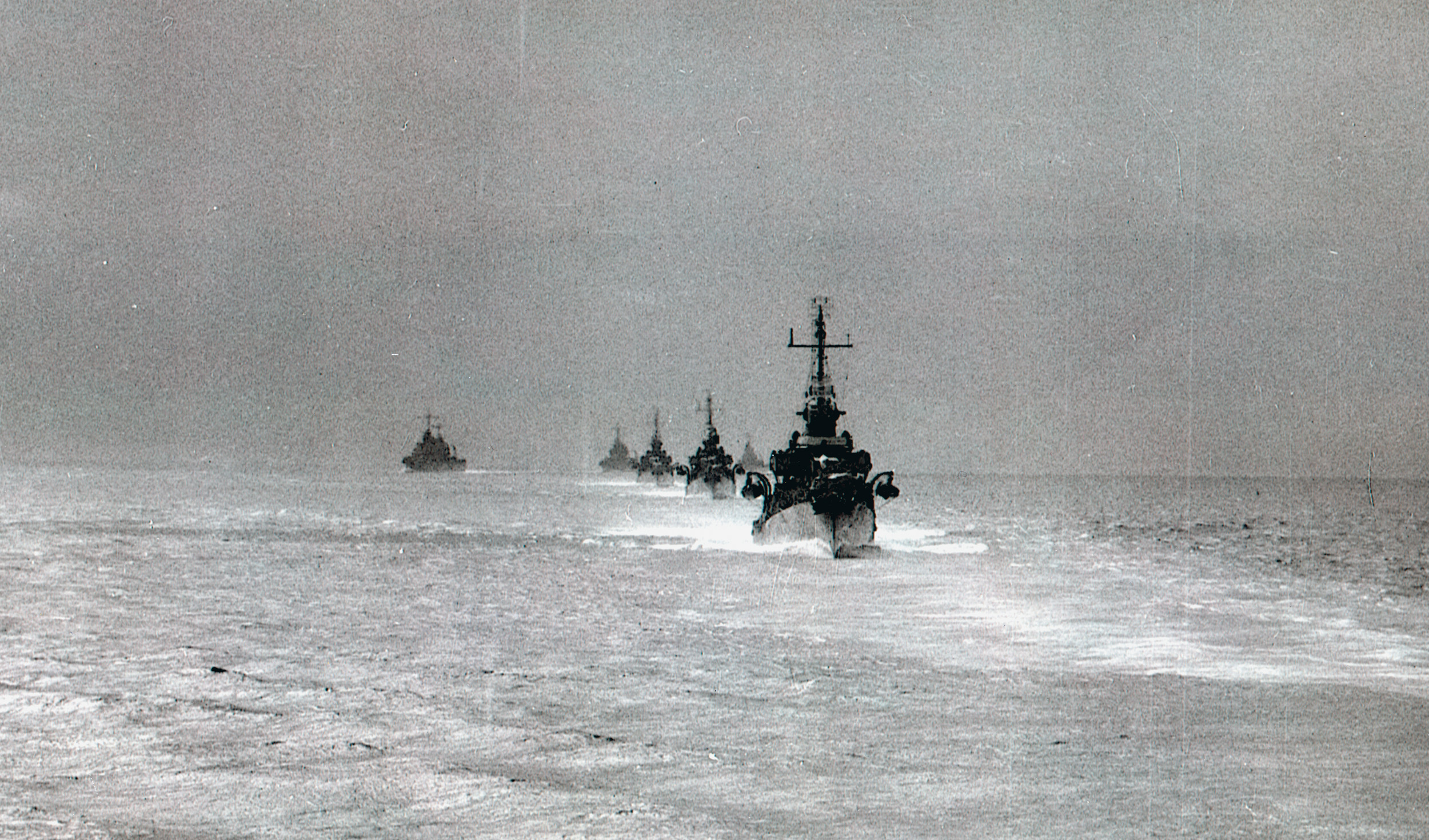

At an average speed of 29 knots, the seven warships of Task Group 36.1 made their way by midnight as far as Visu Point in northwestern New Georgia. General Quarters was sounded aboard all ships as a precautionary measure, and the ships held to a routine, spread-out antiaircraft deployment because no surface opposition was yet in sight.

The sky was moonless and blotted with moderate cloud cover. The sea was tranquil and there was a gentle breeze. Speed was gradually reduced to 27 knots, and then to 25 knots.

Farther to the north, Rear Adm. Teruo Akiyama was leading three groups of destroyers on a dash into Vila Stanmore, where a large complement of Imperial Army troops would be unloaded for eventual deployment on New Georgia. Admiral Akiyama was personally leading his Support Unit, which consisted of the destroyers Niizuki, Suzukaze, and Tanikaze; the First Transport Unit, under the command of Captain Tsuneo Orita, consisted of the destroyers Mochizuki, Mikazuki, and Yamakaze; and Captain Katsumori Yamashiro’s Second Transport Unit was composed of the destroyers Amagiri, Hatsuyuki, Nagatsuki, and Satsuki.

Despite Task Group 36.1’s superiority in fire power, and despite the hindrance of having troops aboard his vessels, Akiyama had the edge. Bad weather had prevented a U.S. Navy PBY Black Cat patrol bomber from scouting the area, and the weather would continue to keep Allied aircraft from the scene. The 24-inch torpedo mounts on Akiyama’s ships were the great equalizer, and the Niizuki was equipped with excellent modern radar. Further, Akiyama was confident; earlier troop runs had been successful and, just the night before, a single destroyer division had reportedly beaten off a large Allied cruiser force after inflicting heavy losses.

At 12:26 am, Admiral Akiyama detached Captain Orita’s First Transport Unit for a run along the coast of Kolombangara to Vila Stanmore. The remaining destroyers continued in column at 21 knots toward the foot of Kula Gulf. At 1:18, the Japanese column reversed course by column movement, and at 1:43, Akiyama dispatched Captain Yamashiro toward Vila while his own Support Unit—the Niizuki, Suzukaze, and Tanikaze—sailed north.

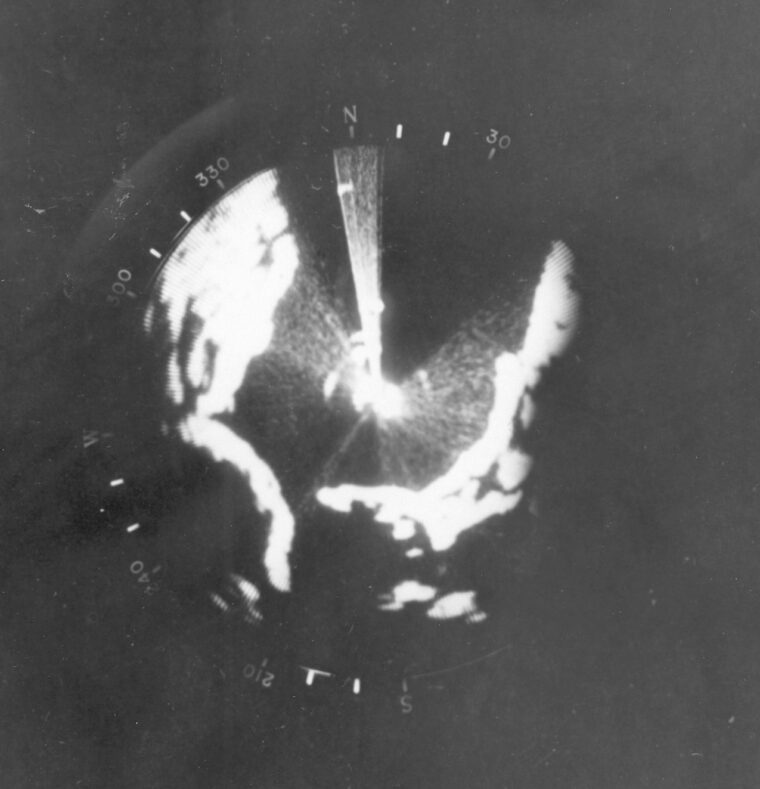

As Yamashiro’s destroyer-transports received their orders for the run to Vila Stanmore, American shipborne radar operators were plotting their tracks. Contact had been made at 1:40 at a distance of 24,700 yards. Orders from Admiral Ainsworth shifted the American column around to battle formation and a full state of readiness. The Nicholas and O’Bannon were in the vanguard; following were the light cruisers Honolulu, Helena, and St. Louis; and the destroyers Radford and Jenkins were the rear guard. They shifted course from 292 degrees to 242 degrees, and held speed at 25 knots.

The CIC plots on all of the American warships were a bit confused owing to the jumbled radar returns caused by Kolombangara’s irregular shoreline, which filled in the background on all the American radarscopes. Additionally Yamashiro’s four-destroyer unit was in the process of peeling off from Akiyama’s supporting column. Nevertheless, by 1:49, American radar had affirmed that the Japanese force consisted of between seven and nine ships, and they knew that there were two separate Japanese groups.

Admiral Ainsworth ordered a 60-degree turn to starboard, which brought his column back to course 302 degrees. Range had dropped to 11,000 yards in the intervening minutes, so Ainsworth decided to engage the Japanese at medium range with radar-controlled gunfire. The Nicholas and O’Bannon were ordered after Akiyama, and the cruisers and rear-guard destroyers would take out Yamashiro.

“Commence firing!” was passed to the destroyers at 1:54. Captain Francis X. McInerney, the commander of Destroyer Squadron 21, asked Ainsworth whether that order specified guns or torpedoes. Ainsworth replied, “Gunfire first, but hold everything.”

Yamashiro’s destroyer-transports were rapidly opening the range. The American admiral ordered his light cruisers to hit the nearer group—Akiyama’s Support Unit—and then “reach ahead, make simultaneous turns, and get the others on the reverse course.” The time was 1:56; the average range to the Japanese ships stood at 7,000 yards.

The Helena, a veteran of many bloody night engagements, was a bit slow getting on her target; she did not open with her 15-gun 6-inch main battery until 1:57. By then, Akiyama’s group was broad on the port beam and down to a range of 6,800 yards. Owing to the lack of flashless powder, the Helena was revealed by her very first salvo. The two other American light cruisers also lit themselves up after firing only two or three flashless salvos.

On the Japanese side, the Niizuki had spotted Ainsworth’s column at 1:47. The Japanese admiral ordered his ships to get up steam for a 30-knot run and to change course 40 degrees from the original heading of due north. Captain Yamashiro was ordered into the fight despite the presence of unprotected infantrymen on his ships’ open deck spaces.

As American gunfire flashed in the night, Japanese torpedomen found their points of reference. But the Niizuki had already been smothered by the first American 6-inch salvos. Her steering was gone, and she veered crazily out of formation. Nevertheless, the Suzukaze and Tanikaze filled the water with 16 of their 24-inch Long Lance torpedoes within a minute of their own admiral’s order to commence firing.

Lieutenant Commander Donald J. MacDonald, master of the veteran destroyer O’Bannon, wanted an opportunity to fire his own torpedoes. Despite the fact that his gunnery officer had come up with a seemingly perfect gunfire solution, MacDonald withheld permission to fire the ship’s five 5-inch guns until he was absolutely sure that his torpedoes would be of no use. The Nicholas’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. Andrew Hill, made an identical decision. Both vanguard destroyers finally got around to firing a few desultory rounds from their 5-inch batteries, and the torpedoes wound up lying idle in their tubes. Commander Harry F. Miller of the destroyer Jenkins and Commander William K. Romoser of the Radford also held their guns in check until torpedo attacks were completely out of the question.

It is interesting to note that the decisions reached by the four destroyer skippers—each acting independently of the others and the light cruisers—were in direct contrast to the methods of attack employed by U.S. Navy destroyer commanders between 11 and 8 months earlier, during the big naval surface engagements around Guadalcanal. Clearly, a study of successful Japanese techniques employed in the numerous night encounters off Guadalcanal had netted a consensus among American commanders that many of the Japanese successes there had been a result of the Imperial Navy’s oft-used stand-off offensive doctrine, in which torpedoes were fired, if possible, before guns were employed. This was in direct contrast to the basic U.S. Navy doctrine in which attacks opened with massed gunfire. The engagement in Kula Gulf on the night of July 5, 1943, was the first opportunity the American destroyer commanders had to test the Japanese doctrine in their own behalf.

At any rate, the cruisers were in the process of pumping more than 2,500 6-inch rounds into the night. All that fire was loosed within the opening five minutes—against a Japanese formation whose survivors later claimed the Americans had employed “6-inch machine guns.” Admiral Ainsworth was convinced that Akiyama’s three supporting destroyers had been written off, but only the Niizuki was fated to sink. The Suzukaze lost her searchlight battery, her forward gun mount, and a machine-gun ammunition locker, and sustained a few minor hull punctures. And the Tanikaze was struck by a single dud in her anchor windlass that accounted for the loss of some rice and barley stores. At 1:59, both of these warships made smoke and retired northward to reload their torpedo tubes.

A few minutes later, Ainsworth ordered his column to countermarch to course 112 degrees. But before that move could be carried out, Captain Charles P. Cecil’s veteran Helena was struck by a Long Lance. By 2:07, she was rocked by two others. The first torpedo sheered off the light cruiser’s bows between Turret-1 and Turret-2, which caused the cruiser to flood. Coming up astern of the Helena, Captain Colin Campbell’s St. Louis cut hard to starboard to avoid collision, then settled down on a course to the east-southeast. A dud torpedo clanged into the Helena’s hull aft just as Campbell’s cruiser cleared the area.

As the American gunfire against the Suzukaze and Tanikaze began to abate, and just as the Radford and O’Bannon sent a combined nine-torpedo spread in a hopeless tail chase after the two withdrawing Support Unit destroyers, Captain Yamashiro’s four troop-laden destroyer-transports began appearing on American radarscopes. The new Japanese arrivals were some 13,000 yards distant and making north at 30 knots. At 2:07, the American column shifted to starboard on course 142 degrees, and at 2:15 it came hard about to port on course 082 degrees.

The Helena was not answering repeated radio queries from her sisters, but Admiral Ainsworth had no time to worry. At 2:18, the Amagiri, which was bearing south-southwest at 11,600 yards, became a target. A few minutes later, Ainsworth again shifted course—this time to 112 degrees. The American admiral was attempting to “Cross the T”—cross in front of the Japanese column at right angles so that his ships’ full broadsides would be opposed only by the forward gun mount of the leading Japanese warship.

The American column’s move was successful. The leading Japanese destroyer, the Amagiri, began taking heavy flanking fire. Upon seeing their shells strike home, the Americans increased the rate of fire. The Amagiri swerved hard to starboard, laid a thick, black smoke cover, and launched several torpedoes. She escaped with only minor damage.

The Hatsuyuki, next in line, was struck by three shells. All were duds, but the damage was amazing considering the lack of explosive force. Her gun director was damaged, communications severed, steering from the bridge ruined, a boiler pierced, the main feedline punctured, and a torpedo mount twisted. In addition, three spare torpedoes were destroyed and five men were killed. The destroyer returned fire as she heeled over hard to port and ran before she had an opportunity to launch any Long Lances.

The Nagatsuki and Satsuki countermarched almost immediately after the encounter erupted and made for Vila Stanmore to land their passengers. Neither ship was hit, and neither fired a shot.

At 2:27, the American warships turned 150 degrees to starboard and headed due west, but there were no targets out that way. The Honolulu, commanded by Captain Robert W. Hayler, fired several rounds here and there while Captain Colin Campbell’s St. Louis fired star shells. At 2:30, Admiral Ainsworth decided that he had put the Japanese to full flight. He shifted course to 292 degrees and the column made for The Slot—New Georgia Sound. At 2:35, the action was conceded as being over and word was passed to “Clear the guns, forward!”

Several ships cleared their guns by firing parting shots at the sinking Niizuki, and some probably fired a few rounds at the Helena’s floating bow section. The Nicholas launched five torpedoes at the Niizuki and then swept on to scout Vela Gulf with her radar, a task she completed without incident by 3:15. The Radford, which moved to scout Kula Gulf, found what appeared to be a ship off Waugh Rock. Rather than attack on his own, Commander Romoser elected to set up a morning air strike against the target.

After shifting the Honolulu and St. Louis to an east-southeasterly heading, Admiral Ainsworth ordered Captain Francis McInerney to remain behind with the Nicholas and Radford to pick up survivors from the Helena.

The Helena’s crew was doing everything possible to abandon ship. Below decks aft of the lost bows, the crew had felt the torpedo hit, but the men in the main part of the truncated ship had no inkling as to the extent of the damage. Clearing these compartments was therefore slowed considerably from the outset, but the second and third hits speeded things up as water began cascading into the engineering spaces.

The captain ordered “Abandon Ship,” and the ship’s CIC Officer, Lt. Cmdr. John L. Chew, supervised the launching of rafts. Then the crew began making its way over the sides, with Captain Cecil waiting patiently in order to be the last man to leave. Six minutes after the order had been passed, the Helena jack-knifed and fell into the 300-fathom deep under her keel. The severed bows remained afloat, however.

Small convoys of life rafts formed, and officers and petty officers led the survivors in shouts of “Hip, hip, hooray!” in hopes of attracting attention to themselves. Sailors with bosun’s pipes began blowing them loudly.

The Radford and Nicholas arrived at 3:41 and immediately began taking survivors aboard. Just as eight bells was struck, and before very many of the survivors had been picked up, the Nicholas made a radar contact with a target approaching rapidly from the west, and the Radford’s CIC came upon a second target coming on strong from the south. With shouts of “We’ll be back,” the rescue ships moved slowly out of the survivor-choked waters.

The unidentified ships coming after the Radford and Nicholas were the Tanikaze and Suzukaze, both of which had reloaded their torpedo tubes and were looking for trouble. However, neither of them spotted the American destroyers or the Niizuki, and they retired following a quick sweep through the area. As they left, the Radford and Nicholas rushed back to continue saving the Helena’s crew.

The Japanese had thus far succeeded in putting about 1,600 troops and their supplies ashore at Vila Stanmore. They had gotten off quite easily. They had sunk the Helena and had accomplished their primary mission at the cost of only one destroyer lost. But it was not to end with the loss of the Niizuki. In clearing Vila Stanmore, the destroyer Nagatsuki ran aground in the treacherously fouled waters in Bambari Harbor. The Satsuki tried to haul the Nagatsuki off the coral, but she had to secure at 4 o’clock in order to be far to the north by dawn, beyond the range of Allied bombers. She and the Hatsuyuki reached Buin safely late in the morning.

The Amagiri, with Captain Yamashiro aboard, steamed along the east coast of Kolombangara toward Kula Gulf. At 5:15, Amagiri lookouts spotted a group of Niizuki survivors in the oil-slick waters and the destroyer slowed to pick them up. Only 13,000 yards to the north-northwest, the Radford and Nicholas were still in among the Helena survivors. The two American warships immediately spotted the Amagiri—whose lookouts spotted them also. Captain McInerney secured the rescue effort, and his ships trained all their weapons on the Amagiri. Captain Yamashiro abandoned his own rescue effort, called for flank speed, and ran to the northwest. At 5:22, the Nicholas launched a half-salvo of torpedoes at a range of 8,000 yards. The Amagiri replied in kind a few minutes later. Both ships escaped damage; the Nicholas’s torpedoes passed ahead and astern the Amagiri, and one Long Lance porpoised a mere 15 feet astern of the Radford.

Both sides opened with gunfire at 5:34. The Nicholas, which also fired star-shell illumination, scored one hit that disabled the Amagiri’s fire-control circuits and destroyed her radio shack. The Japanese captain put up a smoke screen and moved out at top speed. The smoke led the Americans to believe they had set the Japanese ship on fire, but such was not the case.

With the Amagiri’s hasty departure, the Niizuki’s crew was left to its own devices. As a result, the ship’s captain, Rear Adm. Teruo Akiyama, and nearly three hundred officers and crewmen died at sea.

While the rescue operations were under way in Kula Gulf, Captain Orita’s unengaged transport unit was landing troops at Vila Stanmore. When finished, the Mikazuki and Yamakaze steamed through Blackett Channel and safely retired. The Mochizuki needed an extra hour to unload her passengers. When done, she used the Kula Gulf passage. Captain Orita, who was aboard, preferred to hug the coast of Kolombangara and stay out of trouble, but the destroyer was caught in open daylight by the Nicholas and Radford. Both American destroyers opened fire with their guns at a range of five miles. At 6:15, the Mochizuki launched one Long Lance, made smoke, and ran while nursing 5-inch hits in her torpedo and gun mounts. After the American destroyers set four launches with volunteer crews in the water to assist additional Helena survivors, Captain McInerney likewise made smoke and retired toward Tulagi at 6:17 with 745 Helena survivors aboard.

All that remained was the Nagatsuki, which was still high on the reef at Bambari Harbor. At 10:10, the Allied air strike requested by Radford’s Commander Romoser to check out Waugh Rock arrived over Kula Gulf. The 11 SBD dive-bombers and TBF torpedo bombers and their 18 fighter escorts located the Nagatsuki on their own and mounted an immediate attack. By then, seven Imperial Navy Zero fighters were guarding the stranded destroyer, but they provided no protection whatsoever. Four Zeros were shot down by the American fighter pilots, and the rest fled. Although she fired all her guns at the American airplanes, the Nagatsuki was walloped. A second attack, conducted by Army Air Forces B-25 medium bombers of the 42nd Medium Bombardment Group, set her afire. Eventually, before dark, her magazines blew up. Next morning, the survivors began trekking to Vila over the reef that had snared their ship.

Except for the job of picking up the remainder of the Helena’s survivors from the water, the Battle of Kula Gulf was over—a clear American victory.

This was one battle I wrote about in My master’s thesis. It showed how deadly the long lance was even though American forces did not consider it so. Additionally, as the article pointed out, the Allies did not have time to replenish the smokeless powder which proved to be their downfall.