By Nathan N. Prefer

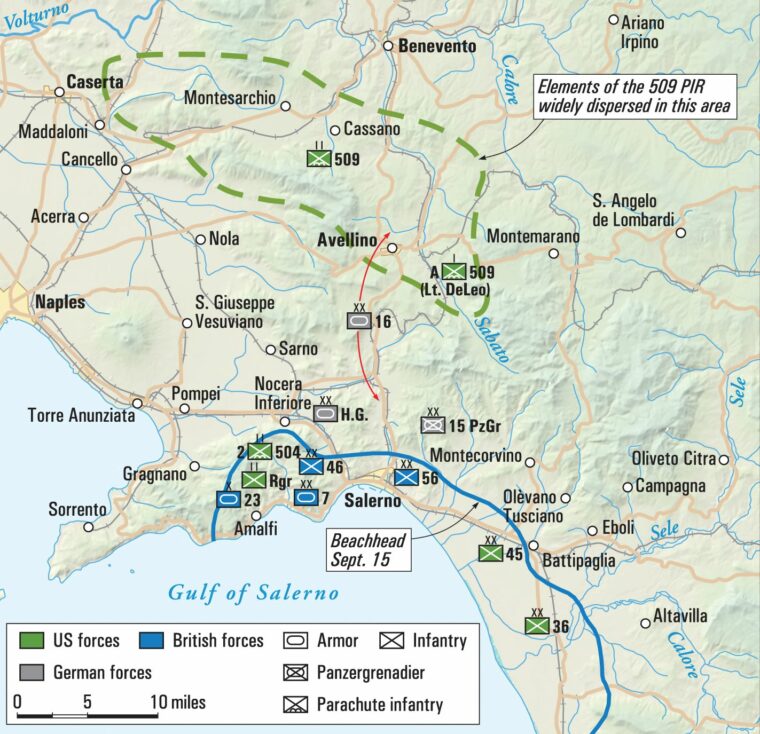

The Fifth U.S. Army was in trouble and dropping 600 paratroops at Avellino to disrupt the communications of the 16th Panzer Division seemed like a sound solution. Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark’s command had landed in Italy at the Bay of Salerno expecting to find little or no opposition. After all, the Italian armed forces had just surrendered, and few German military units were expected in southern Italy. Allied plans like “Gangway” and “Barracuda” were envisioned as easy landings with an overland march directly to Naples, where follow-up forces would come ashore at that port with dry feet. It was to be “wine, women and song” all the way to Rome. But things were not working out as planned.

Unknown to the Allies, the Germans had made plans to take over the coastal defenses—Plan Asche—after the Italian surrender. When it came, the Germans moved swiftly. The German force assigned to Salerno was the LXXVI Panzer Corps with the reconstituted 16th Panzer Division under command. Formed from the 16th Infantry Division in 1940, this veteran unit had fought on the Eastern Front at Lvov, Taganrog, and other battles before being destroyed at Stalingrad. Rebuilt with survivors, veterans, and recruits, it had trained in France before moving to Italy where it was assigned to defend the Salerno Bay area. Its major units were the 2nd Panzer Regiment, the 64th and 79th Panzergrenadier Regiments, and the 16th Panzer Artillery Regiment. Generalmajor Rudolf Sieckenius commanded the division at the time of the Salerno battle.

Barely had the 16th Panzer Division settled into the Italian defenses above the Bay of Salerno when the Fifth U. S. Army arrived. General Clark’s forces consisted of the VI U.S. Corps under Major General Ernest J. Dawley and the X British Corps under Lieutenant General Sir Richard L. McCreery. One American and two British divisions, reinforced with Ranger battalions and Commandos, made up the assault force. The attack began on September 9, 1943.

The landings at Salerno were intended to speed up the conquest of southern Italy, which had already begun when Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s Eighth British Army had landed on the Italian “toe” on September 3, 1943. But the Germans were delaying the Eighth Army’s advance with demolitions and ambushes. A landing behind their lines, at Salerno, might force a more rapid withdrawal. The surrender of the Italian Armed forces also raised Allied hopes of a swift move on Rome.

But from the first landings at Salerno, it was clear that the 16th Panzer Division had no intention of withdrawing. Their defenses stood firm against the novice Americans of the 36th “Texas” Infantry Division and the British veterans of the 46th West Riding and 56th City of London Infantry Divisions. The Battle of Salerno quickly became a vicious and bloody struggle to remain ashore or be pushed back into the sea.

Major General Fred L. Walker’s “Texans” fought desperately at Altavilla, where three Medals of Honor were awarded and the 1st Battalion, 142nd Infantry, was reduced to just 60 remaining soldiers. The Germans also made a dangerous thrust along the Sele River corridor, threatening to split the Allied beachhead in two. Across that river, Major General J. L. I. Hawkesworth’s West Riding and Major General D. A. H. Lyne’s City of London Divisions were equally hard pressed. General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, commanding the Tenth German Army, was determined to throw the Allies into the sea or destroy them on the beaches. Knowing that the 16th Panzer Division alone could not both hold the beachhead perimeter and successfully counterattack, he called up his reserves, including the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, the 29th Panzergrenadier Division, and later the 26th Panzer Division.

By September 13, the situation of the Fifth Army at Salerno was increasingly desperate. The last reserves, the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment and the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, had been thrown into the battle as infantry. Even the landing of most of the 45th “Thunderbirds” Infantry Division under Major General Troy H. Middleton failed to turn the tide. A withdrawal to a final beachhead line was ordered, and General Clark sought further assistance from beyond Fifth Army resources.

Field Marshal Montgomery’s Eighth British Army had halted to reorganize and was still too far south to be of any help. General Clark and his staff had already discussed with Rear Admiral H. Kent Hewitt preliminary plans for an evacuation of either the American or British beaches, depending upon developments. Admiral Hewitt objected that such an operation was technically impossible. He pointed out that it was easy to retract a landing craft from the beach after it was emptied but quite another thing once it was fully loaded. Despite his concerns, Admiral Hewitt met with British Admiral G. N. Oliver who raised the very same concerns. Nevertheless, ships and landing craft were placed on a half-hour alert for movement to the sea outside of the range of shore-based artillery in preparation for an evacuation. Later, General McCreery would also object to evacuating his X British Corps.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Mediterranean theater commander, had offered General Clark the 82nd Airborne Division’s two parachute regiments as an immediate reinforcement. Others would have to come by sea, taking days to arrive—time the Fifth U.S. Army did not have to spare. Clark accepted and asked that the regiments be dropped within the beachhead as soon as possible. The drop would occur that very evening, September 13.

General Matthew B. Ridgeway, commanding the 82nd Airborne Division, turned to Colonel Rueben H. Tucker, commanding the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), for the drop. First, åGeneral Ridgway made sure that there would be no repetition of the tragedy during the Sicily invasion, where Allied ships off the beachhead had mistaken his paratroopers for the enemy and opened fire on their aircraft, killing and drowning many. Once assured that every ship had acknowledged the upcoming airborne drop, he prepared for the actual operation by assigning a drop zone five miles north of Agropoli, a flat area about 1,200 yards long and 800 yards wide between the sea and the coastal highway.

Then the 2nd Battalion, 504th (PIR), boarded its planes and began its flight into the Salerno beachhead. Forty-one aircraft dropped the battalion at 0130 hours on September 14. The 1st Battalion followed, and by 0300 hours on September 14, Colonel Tucker reported to VI Corps headquarters that he had 1,300 troops available for the defense of the beachhead.

Not everything went smoothly for the 504th PIR. One company landed eight miles from the drop zone, a result of pilots’ confusion and poor navigation. On the German side, a Lieutenant Rocholl, commanding three armored vehicles of the 16th Panzer Division’s Reconnaissance Regiment was enjoying his first good night’s sleep in many days when a guard awakened him to report enemy paratroopers landing nearby. He stepped into the night to see 50 or 60 paratroopers about 500 feet high swinging down in their parachutes. He could faintly hear aircraft in the distance. The bright moonlit night showed every detail of the descending enemy troops.

The Germans rushed to their armored cars and swung the barrels of their 20mm cannon and their machine guns to fire at the descending enemy. They fired until the paratroopers were too low to continue without hitting friendly forces. Most of the Americans landed further up the mountain on which Lieutenant Rocholl’s company had bivouacked. The Germans immediately moved to reconnoiter the area, searching houses, but at first found no enemy soldiers. As they came to the last house, Lieutenant Rocholl knocked at the door, finding it locked. When there was no response, two of his men kicked in the door and ducked just as a burst of automatic weapons fire came from inside. The Germans replied with two grenades and their own automatic weapons. When the dust and smoke cleared Lieutenant Rocholl found several wounded American paratroopers who surrendered. As he left, he noticed several other shadowy figures racing further up the hill but declined to chase them in the dark.

The German counterattack continued on September 14, but the senior German commanders were beginning to realize that they could not compete with or overcome the great advantages the Allies had in naval gunfire and air support. Combined with the increasing artillery fire from the beachhead and another reinforcing drop by Colonel James Gavin’s 505th PIR, the German command soon decided to withdraw from Salerno. Unaware of this development, the Allies still feared the enemy would bring more strength against the beachhead, and so another airborne operation was planned. This one was intended to aid the X Corps, which had suffered the brunt of the German counterattacks. A separate battalion of American paratroopers, the 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR, would be dropped well behind enemy lines to harass German communications and delay the arrival of German reinforcements.

The 2nd Battalion, 509th had an unusual history. It began as a separate battalion designated as the 504th Parachute Infantry Battalion. In February 1942, it was redesignated as the 2nd Battalion, 503rd PIR, then training at Fort Benning. In July of that year the battalion was abruptly shipped overseas to Scotland, never to return to the 503rd PIR, which created a new second battalion. While in Scotland the battalion trained with the British 1st Airborne Division. At this time, the battalion received a new designation, as the 2nd Battalion, 509th PIR (Separate). The rest of that regiment was never formed. Later, on December 10, 1943, the battalion would become the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion.

The “orphan” battalion jumped into Algeria and Tunisia, making the first three combat jumps in American parachute history. The battalion was then attached to the 82nd Airborne Division but was not used during the Sicily operation. Lieutenant Colonel Doyle R. Yardley took being ignored hard and his troopers were eager for the next operation.

With the two parachute regiments of the 82nd Airborne Division already fighting at Salerno, the plan to disrupt the enemy’s rear areas needed another airborne unit. There was only one other available in the theater, and that was the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion. General Clark had requested that they drop on the night of September 12, but that left insufficient time for preparation. Instead, the planners moved to the following night, and General Clark, when queried as to which operation had priority, the drop into the beachhead or the one behind enemy lines, unhesitatingly designated the latter as the priority operation.

The drop zone was a crossroad about three miles southeast of the town of Avellino. The mission was described as a five-day harassment of the Germans, after which the paratroopers were to withdraw to Allied lines by infiltration, unless the Fifth Army had reached its area by then, an unlikely occurrence given the situation at Salerno. Even with the one-day postponement, haste marked the operation. No intelligence of the area or the German defenses could be found. Aerial photographs only became available on the afternoon before the drop. The maps available were at a scale of 1/50,000, much too large for use by company and platoon leaders. Even then, they showed only Avellino and its immediate environs. Because the battalion had to travel two hours to reach its departure airfield, the commanding officers had barely two hours to study the maps and photos before loading. There was no time to have a commanders’ conference before departing.

The men of the battalion had been expecting a call to Salerno, believing that they would join the 504th and 505th PIRs there. They had been waiting in Sicily, sleeping on their parachutes. The call came, not for Salerno but a place called Avellino about which they knew nothing. They were told that only service troops would be in the area, although a German panzer division was expected to pass through in a “few days.” The men were told that if anything went wrong, they were to head south toward British lines. The battalion doctor, Captain Carlos “Doc” Alden, wrote “We’re all nervous. Hiding it well. I read. Colonel sleeps. Others talk. We’re ready for whatever comes.”

The 600 men of the battalion boarded 40 aircraft in Sicily and set off for Avellino. Navigational errors and poor radar results, along with the failure of the Aldis lamps carried by their pathfinders, combined with a high jump altitude at 2,000 feet to scatter the paratroopers as far as 25 miles from the drop zone. Two plane loads simply disappeared for the next two months before they were located. Only 15 planeloads landed within five miles of the target.

Once on the ground the paratroopers found that they had landed in broken terrain, making it impossible to concentrate into large groups. Thick woods and vineyards made organizing even more difficult. Most of their heavy equipment, including mortars, machine guns and bazookas, was lost or irretrievably hung up in the trees. Faced with these unexpected difficulties, the paratroopers coalesced into small groups of five to 20 men and did their best to avoid detection while mounting raids on supply trains, truck convoys, and isolated outposts.

Doc Alden had a frightening jump. As he descended, he looked down to see that he was heading directly for a well. With all his equipment, he was sure to drown if he fell in. Despite his best efforts to avoid it, he fell into the well and found himself up to his waist in water. Using his parachute risers as a ladder, he climbed out and moved toward the drop zone. As he moved, he was struck by the quiet. Given the fact that a battalion of paratroopers had just dropped into the area, it was surprisingly quiet. Not a shot was heard. He came upon an Italian civilian, who informed him that there were about 250 German soldiers in trucks two or three miles up the road toward the drop zone.

Lieutenant Colonel Yardley had reached the drop zone and gathered as many men as he could. With perhaps 100 troopers, he set off for the crossroads to accomplish his mission, or to at least cut the German lines of communication in the area. Doc Alden’s Italian civilian guided them for a mile and then disappeared. Lieutenant Colonel Yardley stopped his column to decide what to do without a guide. Deciding that the guide had left because he was scared, the column moved forward, only to come under fire from several machine guns. Enemy flares lit up the night. A fierce firefight began.

The fighting continued for several minutes, but the Germans soon added tanks and 88mm anti-tank guns to the fray. Aiming these guns at clusters of paratroopers, they soon forced the group to disperse. Lieutenant Colonel Yardley was one of those seriously wounded in this battle. As he lay defenseless on the field, German soldiers came up to him and prodded him with bayonets. Others dragged him to an aid station. Lieutenant Colonel Yardley’s part in the Italian Campaign was over.

What Lieutenant Colonel Yardley and his men did not know was that a few days before they jumped an entire regiment of the 16th Panzer Division had moved into the area. The thought that they faced only “service troops” was now a thing of the past. But the dispersed jump had worked to their benefit. Since they were so widely spread out, the Germans had no center of gravity to attack and had to deal with each small group of paratroopers as they revealed themselves, causing a significant waste of time and effort on the part of the Germans. But that made it no easier for the troopers.

Staff Sergeant William Sullivan later recalled his experiences. “Not long after the jump, Christ, it seemed the whole German army moved into the area, and they were hunting for us—they were hunting for us like rabbits. That scared the hell out of me. They were going up and down the rows of corn and shooting anything that moved…. The idea of being captured or the idea of someone hunting you scared the…out of you … there’s nothing you can do, you have to hide.”

Many of the survivors of this fight, including Doc Alden, managed to crawl away in the darkness. Most of the Italian civilians in the battle zone were willing to help the Americans get away, hiding them and providing food before passing them along to others at a distance. At one stop, Alden found some wounded paratroopers in a house and treated their wounds. As he emerged, he was captured by German soldiers and taken back to the battle area of the previous night. During his interrogation, Alden learned much about the German dispositions. Sent to a German field hospital where he was to treat British and American wounded, he enjoyed a three-day respite, eating with the German commander of the hospital before escaping. Thirty miles behind German lines, the paratroop doctor was hidden by Italian civilians until Allied forces arrived.

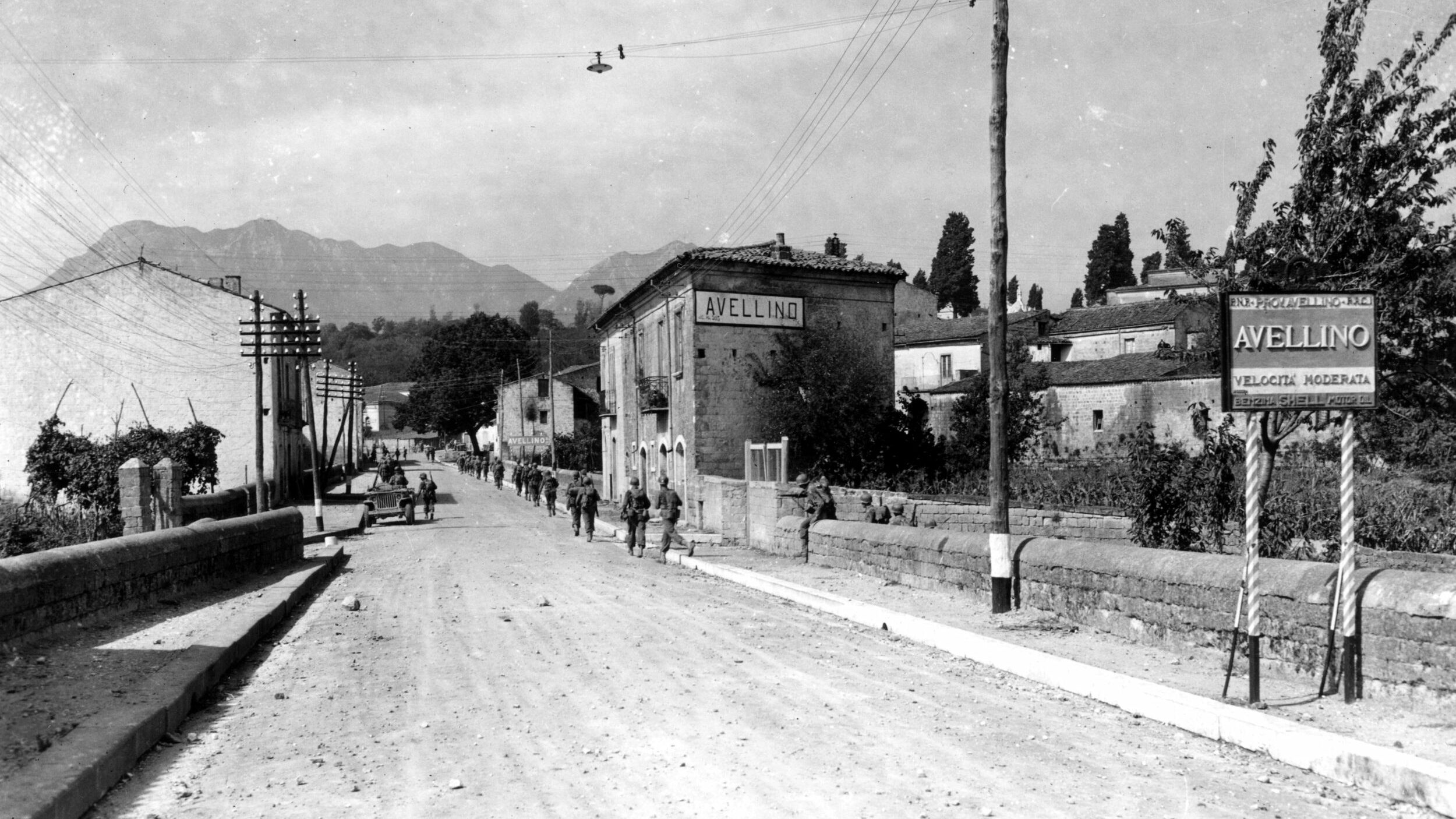

Lieutenant Daniel DeLeo and his platoon of Company A had landed a few miles from Avellino. As soon as they landed, they came under fire from the enemy. Four paratroopers were wounded. The rest faded away into the darkness, taking the wounded with them. They found a cave and sheltered there for the rest of the night. After a few days, Lieutenant DeLeo contacted local civilians who provided food but had no medical care available for the wounded. Wearing civilian clothes, Lieutenant DeLeo and some of his troopers went into the local village and kidnapped a Fascist doctor under the noses of the German troops there. Once out of the village, the doctor cooperated, treating the wounded, and stayed for several days to supervise their recovery.

Despite some who thought the doctor could not be trusted to keep their position a secret, Lieutenant DeLeo released him after making him promise that he would not reveal their location. He reminded the doctor that Allied forces were approaching the area and that if he betrayed them there would be consequences. So convinced was the doctor that he never revealed their presence and even came back every few days to see how the wounded were progressing.

While hiding in the cave, the paratroopers made several forays against the Germans. One evening, they ambushed a German motorcycle courier, hiding his motorcycle in the woods for future use. On others they ambushed individuals or small groups of Germans traveling through. When British troops arrived in the area, the Americans made sure to repay their Italian friends without whom they would not have survived. They seized an abandoned Italian Army supply depot and distributed its contents to those families who had helped them survive behind enemy lines. The former fascist doctor was plied with enough medical supplies to last him quite a while. Arms and military equipment went to Italian partisans.

The battalion executive officer, Major William Dudley, had found about 50 paratroopers from the jump. Some 40 miles from Allied lines and 20 miles from Avellino, he began a march south to Avellino. Before daylight, his group hid on a steep hill overlooking an unknown village. Some stragglers from his column had stayed in the town, and German troops now engaged these few in the village. Outnumbered and with no heavy equipment, Major Dudley could do nothing to help. He at first decided to remain hidden and await the arrival of Allied forces, but his men strongly objected and wanted to take an active part in the battle.

Advised by a local civilian that there was a bridge which served a large amount of German traffic nearby, Major Dudley reconsidered his position. The paratroopers had 25 pounds of TNT with them, and this could be used on the bridge, severing a German supply line. Major Dudley led a reconnaissance along with the battalion supply officer, Captain Edmund Tomasik, Sergeant Joseph Buchanan, and Private Jack Alongi. The bridge was near the village of Montello, and a nearby mountain would provide a good position for the Americans to watch the traffic.

A plan was made in which Lieutenant Justen McCarthy would place the TNT on the bridge, covered by two security teams, one at each end. The rest of the force under Major Dudley would take positions on the mountain to cover the others with fire support. Waiting for the German guards to relax, and with no traffic on the bridge, Lieutenant McCarthy and Private Guy Jeanes were placing explosives on the bridge when a German scout car approached. In an instant, the paratroopers on the hill opened fire on the scout car, which skidded into a ditch. The car’s occupants opened fire, and the paratrooper security teams returned fire.

Under this barrage, Lieutenant McCarthy and Private Jeanes completed their placement of the explosives and jumped over the side of the bridge into the stream below. After gathering his security teams, Lieutenant McCarthy escaped and joined the main force on the hillside. As they ran, the TNT exploded, creating a large hole in the center of the bridge. A German truck, unwarned by the bridge guards, proceeded onto the span and blew out its tires on the new hole. The paratroopers on the hill opened fire again, killing a reported six enemy soldiers and backing up traffic for a mile the following day. Two weeks after they had landed, Major Dudley’s forces were contacted by the advancing Allies.

These activities and the widely scattered nature of the drop convinced German intelligence officers that the entire 82nd Airborne Division had dropped behind their lines. Captured paratroopers were soon being asked the whereabouts of Colonel Tucker of the 504th Parachute Infantry and Colonel Gavin of the 505th Parachute Infantry. The association of the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion with the 82nd Airborne Division was known to German intelligence.

Whichever way it is portrayed, the drop of the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion at Avellino was a desperate venture. In a post-mortem of the battle the battalion cited several reasons for the ineffectiveness of the Avellino operation. These included insufficient time allowed for briefing and equipping the troops; orders to carry five days’ rations and five days of ammunition overburdened the troopers physically; and no radio procedures or schedules were worked out to ensure communications. Nor was there an opportunity to secure special radio equipment to maintain contact with the Fifth Army.

Although the Avellino drop did cause confusion behind the German lines and briefly interrupted the lines of communication of the 16th Panzer Division, it had no significant effect on the outcome of the Salerno battle. In fact, the day after the paratroopers had dropped, and before they could possibly have had any effect on the battle, General Clark was declaring the battle won.

Miraculously, of the 641 men who jumped at Avellino eventually more than 400 returned to Allied lines. Another 115 were killed, captured, or listed as missing. Some of these missing returned after the war from prison camps. Lieutenant Colonel Dudley escaped from a German POW camp in January 1945 and made his way successfully to Russian forces, where he spent two months with Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s Fifth Soviet Army. He was then sent to Odessa, where he joined hundreds of other liberated Allied POWs. Eventually, these men were shipped home.

Doc Alden continued to serve with the battalion, earning a Distinguished Service Cross, a Silver Star, and other awards for gallantry. He was the only member of the battalion to have a book written about him—Captain Cool: Paratrooper Legend. General James Gavin of the 82nd Airborne Division would call Doc Alden “the bravest of the brave,” while Lieutenant General William P. Yarborough, who had once commanded the battalion in his long military career, called him “the most gallant paratrooper doctor of them all.”

Captain Edmund J. Tomasik, who had fought at the bridge battle near Avellino, would be the only officer of the battalion to serve in it from organization to disbandment. He would be the battalion’s last commander, as Major Tomasik. After 30 years in the army holding ranks from private to colonel, he retired with a Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, a Purple Heart, and other decorations.

The “bastard” battalion was reorganized, and replacements were integrated. Lieutenant Colonel William P. Yarborough assumed command and Tomasik replaced Major Dudley as executive officer. The battalion was relieved from the 82nd Airborne Division and assigned as the honor guard for Fifth Army Headquarters in recently captured Naples. A detachment was sent to take some offshore islands, which they did successfully. A recommendation for a Distinguished Unit Citation for the battalion’s work at Avellino was submitted but never approved. Some veterans think it was because officers involved did not want to bring attention to such an abortive operation occurring under their command.

The battalion went on to fight in Italy at Venafro under the command of Colonel William O. Darby and his Ranger Task Force. While fighting at Mount Croce, its official designation changed once again, to the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion. The battalion next went to Anzio, still attached to Darby’s Rangers. When the Rangers were destroyed, the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion was attached to the 3rd Infantry Division, remaining at Anzio throughout the fighting there. It was at Anzio that the battalion earned one of its two Presidential Unit Citations.

The invasion of southern France followed. The battalion was part of an ad hoc airborne task force consisting of many individual airborne and glider troops which dropped around Le Muy near the French Riviera. Resistance was light, and the advance inland soon relieved other paratroopers. The First Airborne Task Force, under the former commander of the 1st Special Service Force (Devil’s Brigade), Brigadier General Robert T. Frederick, then protected the flank of the advancing Seventh Army in what has come to be known as the Champagne Campaign.

By December 1944, the battalion was back with the 82nd Airborne Division in France. When the Battle of the Bulge began, the battalion, like the rest of the American airborne forces, was in reserve. Together with the separate 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion and the 517th PIR, the battalion was ordered to report to Bastogne and the 101st Airborne Division, but before it could arrive its orders were changed. It was instead told to report to the 3rd Armored Division near the town of St. Vith.

Suffering from the cold and with inadequate winter clothing, the paratroopers were parceled out to the various task forces of the 3rd Armored Division as added infantry. Individual companies fought at Parker’s Crossroads, Manhay, Sadzot, and other fiercely contested crossroads in the Ardennes. For these actions, the battalion would receive its second Presidential Unit Citation, and Company C would win a third.

After a brief rest, the understrength battalion was attached to the 9th Armored Division and trained to act as armored infantry. Then, along with the 2nd Battalion, 517th PIR, the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion was assigned to the 7th Armored Division for the retaking of St. Vith. Paired with the armored division’s tank battalions, the force advanced on January 19. Attacking in blizzard conditions, they fought German paratroopers defending the town. By the time the battle was over, the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion had about 120 men fit for duty, less than the normal strength of a parachute company. Consolidating its strength into two companies, the battalion continued to attack to clear the St. Vith area for the next several days.

St. Vith was the end of the war for the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion. On January 27, orders arrived at battalion headquarters announcing the deactivation of the battalion. The officers and men were assigned to other units. The men were told on January 29, and things moved swiftly afterward. Major Tomasik led a group to the newly arrived 13th Airborne Division. Others went to the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

The Army adopted an organization table increasing the size of airborne units to regiment or division, with no smaller, independent battalions. During its brief career it had earned eight battle stars, three arrowheads (for three invasions), two Presidential Unit Citations (plus a third for Company C), the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Star, and two Army and two Corps commendations. Members of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion had personally earned one Medal of Honor, 10 Distinguished Service Crosses, 62 Silver Stars, six Croix de Guerre with Silver Stars, five Legions of Merit, and many other decorations.

But the record and accomplishments of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion were not forgotten. Under the U.S. Army’s Combat Arms Regimental System (CARS), the lineage of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, including their campaign credits for Algeria, French Morocco, Tunisia, Naples-Foggia, Anzio, Rome-Arno, Southern France, Rhineland, and the Ardennes-Alsace campaigns reside with the reactivated 509th Infantry Regiment of the regular United States Army.

Nathan Prefer is the author of numerous books and articles on World War II. He received his Ph.D. in military history from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments