By A.B. Feuer

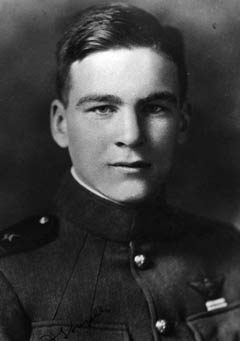

Although U.S. Army Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s victories in World War I were exceptional feats, the exploits of his naval counterpart, David S. Ingalls, remain virtually unknown. Both men were from Ohio, but that is where the similarity ends. David Ingalls was born in Cleveland on January 28, 1899 and was destined to become the only U.S. Navy ace of the war.

In 1916, at the age of 17, David Ingalls entered Yale University where he took up flying by joining the university’s flying club. The organization, founded by F. Trubee Davison, became known as the First Yale Unit. The members were wealthy students who were able to purchase their own airplanes.

Ingalls was an exceptional student pilot but, because of his young age, was not permitted active-duty status. He continued flying, however, and was accepted for active duty on his 18th birthday. Ingalls graduated from flight school as U.S. Navy Aviator Number 85 and went overseas in September 1917.

While waiting for new planes to arrive from the United States, Ingalls was assigned to various squadrons in England for further training. On July 9, 1918 he was transferred to the Allied Naval Base at Dunkirk, France and attached to RAF Squadron 213 for combat experience. The squadron flew Sopwith Camel fighters and escorted bombers in raids on German airfields in Belgium. With the exception of heavy antiaircraft fire, the attacks were usually unopposed by enemy planes. The Camel’s reputation had made the German pilots wary of trying to engage the faster and more maneuverable British aircraft.

After two weeks of what he called “exhilarating work,” Ingalls was sent to Flanders to help with the construction of a flying field for the U.S. Navy’s Northern Bombing Group. He was unhappy with this boring duty, however, and managed to wrangle permission to rejoin his squadron.

David Ingalls: Making U.S. Navy History

Once back at Dunkirk, it did not take long for David Ingalls to begin making U.S. Navy history. While on patrol with an English pilot, he sighted a two-seater German Albatross. The enemy pilot spotted the Camels at the same time, and dashed toward Ostend. The hungry Camels raced in pursuit—firing 150 rounds in short bursts. The Albatross quickly began to smoke—went into a slow spin—and plunged to earth in flames.

In articles about his exploits published in The Cleveland Plain Dealer, Ingalls described the daily routine of flight operations from the naval air station: “There were several kinds of patrols. Planes engaged in ship escort duty flew at low altitude—always within sight of the fleet—during Allied destroyer sorties against German bases on the Belgian coast. Very few enemy aircraft were seen during these missions, but our pilots could always look forward to a cold bath in the event of engine failure.

“In good weather, regular patrols were usually flown twice a day—morning and evening—when enemy aircraft were also out en masse. Two flights were sent up during these patrols—one above the other for protection. Every time we clashed head-on with the Germans, it developed into the most confusing air battle imaginable. Friend and foe swarmed about the sky in all directions. The roar of motors, chatter of machine guns, and the zip of bullets past the ears was like a deadly serenade. Midair collisions were not unusual. A couple of times, I witnessed enemy planes smash into each other.

“If the weather was bad, we flew small patrols up the coast, and below the clouds, looking for German seaplanes. They were fond of flying in stormy weather.”

“In addition to our regular patrols, we often accompanied bombers to Brugge, Zeebrugge and other enemy bases. We were seldom attacked while on these missions, because the Germans were reluctant to take on an armada of 30 or more bombers and fighters.”

In the early morning of August 13, RAF Squadron 213 carried out one of its most successful raids against the large German aerodrome at Varsenaere—about 20 miles southeast of Ostend. Two Camel flights took part in the attack. One group was fitted with phosphorus bombs, and the other with 25-pound shrapnel bombs.

Ingalls recalled the mission: “Considerable confusion was created by taking off in the pre-dawn hours, since a Camel is difficult enough to fly in the daytime. But finally everyone was climbing toward 10,000 feet where we were to rendezvous with another squadron. By the time we reached our assigned altitude, the sky was beginning to lighten, and it was possible to make out the shadowy shapes of the aircraft that were to join us. The leaders of the different flights flashed signal lights to get their men in formation, just as the first rays of sunlight appeared over the horizon.

Ingalls recalled the mission: “Considerable confusion was created by taking off in the pre-dawn hours, since a Camel is difficult enough to fly in the daytime. But finally everyone was climbing toward 10,000 feet where we were to rendezvous with another squadron. By the time we reached our assigned altitude, the sky was beginning to lighten, and it was possible to make out the shadowy shapes of the aircraft that were to join us. The leaders of the different flights flashed signal lights to get their men in formation, just as the first rays of sunlight appeared over the horizon.

“We flew along the coast until midway between Ostend and Zeebrugge, then dived and headed inland. Evidently the enemy was still asleep, as no antiaircraft fire greeted us until we were roaring above the countryside at 200 feet. Our objective soon came within sight, and the squadrons split up.”

David Ingalls pushed his throttle to full power and raced across the airfield. With his wheels almost touching the ground, he sprayed 450 rounds of machine-gun bullets into a line of Fokkers about ready to take off. Then, pressing for altitude, Ingalls zoomed his Camel low over the defending antiaircraft batteries. Barely escaping enemy fire, he banked his plane in a wide circle, threw the Camel into a dive, and headed for the hanger area. Quickly picking his target, Ingalls released four shrapnel bombs. Explosions ripped through a hanger and a searchlight emplacement.

“The Attack Rapidly Developed into a Grand Melee”

Ingalls continued his account: “For several minutes, we were busy diving, turning and shooting in all directions. The attack rapidly developed into a grand melee with many near collisions. The frightful blasts of shrapnel bombs—combined with the deadly clouds of phosphorus smoke—created a hellish scene right out of Dante’s Inferno.

“Finally, before we killed each other, our squadron commander fired a flare from hisVery pistol—the signal to return. We almost clipped the treetops streaking for home.”

As Squadron 213 hurried back to Dunkirk, all remaining machine-gun ammunition was expended over German trenches. The mission had accomplished its objective, and all Camels returned safely to base.

Large-scale air attacks of this kind were infrequent, since their success usually depended upon the element of surprise. During a major infantry advance, however, Allied squadrons staggered their flights over German trenches so that there was always a group of planes covering the enemy’s lines of communication and looked for targets of opportunity.

On September 15, David Ingalls participated in a surprise raid on the German aerodrome at Uytkerke. Using the same tactics that proved so successful at Varsenaere, Ingalls dived out of the clouds—dashed low across the enemy field—and fired four hundred rounds into a camouflaged hanger. He then pulled up sharply, made a tight circle, whipped across the flight line, and dropped four shrapnel bombs on a group of Fokkers.

Returning to Dunkirk, Ingalls and his wingman, British Lieutenant H.C. Smith, were just west of Ostend when they sighted a German two-seater Rumpler reconnaissance aircraft. The enemy pilot noticed the Camels about the same time and dived toward Ostend. Ingalls and Smith quickly followed. The Camels were much faster, and a few machine-gun bursts at close range sent the Rumpler crashing in flames.

Three days later, while patroling near Ostend with two other Camels, David Ingalls sighted an enemy observation balloon at 3,500 feet. These so-called gasbags were tantalizing targets, but were well defended by antiaircraft guns and captured many an inexperienced pilot in their deadly webs.

Ingalls vividly described the dangers involved in trying to shoot down an observation balloon: “We flew up the coast at 8000 feet—just beneath a thick layer of clouds. Opposite Ostend, we turned inland and, nosing over slightly to pick up speed, we approached the balloon in a wide curve.

“The enemy guns had plenty of time to get our range, and accurate antiaircraft fire rapidly began to blister the sky. One shell exploded under the right wing of my plane—sending shrapnel ripping through the fuselage—barely missing my legs.

“As we dived on the balloon, the German ground crew began hauling it down. We attacked the gasbag from different directions, but our bullets had no effect. I made a quick turn, gained altitude, and dove again. This time, I kept firing until I had whipped past the target. Looking back, I saw the two observers jump from the basket. Their parachutes opened just as a burst of flame shot up from the balloon. Within seconds, the gasbag exploded into a ball of fire—then collapsed and dropped on three balloon sheds. The buildings also promptly erupted in flames.

“My Incendiary Ammunition Would Be Perfect Gift for a Surprise Party”

“All three of our planes were pretty much shot up. During the flight home, I noticed a group of German wooden barracks partially hidden by a grove of trees. My incendiary ammunition would be a perfect gift for a surprise party. I dived and raced in low, shooting at the largest target. The bullets must have struck something flammable. The building exploded and, in moments, the entire complex was engulfed in flames. I was machine gunned from the ground—but nothing to worry about. Dunkirk was a welcome sight however.”

In recognition for destroying the enemy observation balloon, David Ingalls was appointed acting commander of the 213 Squadron. And, on September 20, he was assigned to lead three flights, of five Camels each, as fighter escorts for the 218 Bombing Squadron. The dangerous mission was a daylight raid on the heavily defended town of Brugge.

Ingalls recounted the anxiety and excitement of aerial combat: “We rendezvoused with the bombers at 15,000 feet over Dunkirk. A Camel group was positioned on each flank of the 218 Squadron, while another group flew overhead to protect against an attack from above. My flight guarded the starboard side of the bomber formation.

“We flew three miles out to sea, then headed northeast, and turned inland near Zeebrugge. The Germans were ready for us. Upon reaching the enemy coast, we were greeted by heavy antiaircraft fire. I suddenly noticed four Fokkers to my right. They were some distance off, but coming in fast. I signaled my group to attack. We turned to meet the enemy head-on. I aimed for the lead Fokker and fired a few bursts. The German dived—probably hoping that I would follow. But, I was not that foolish. We were over enemy lines, and many an Allied pilot had lost his life when he came within range of ground-based machine guns.

“I took a quick look around. The bombers, and escorting Camels, were nearing Brugge. I hurried to join them. I noticed three Fokkers circling in the vicinity, but they did not attack our formation.”

As the bombers returned from the raid on Brugge, the enemy fighters hovered like hungry vultures—waiting to pounce on any damaged aircraft. Ingalls continued his account: “One of the bombers was having motor trouble. It was losing altitude and began to drop behind. Two Fokkers raced in for the kill. The lead German began shooting at the crippled bomber. I darted to the rescue—banked at right angles toward the enemy—and fired several bursts. The Fokker began to smoke, and dropped to earth in flames.

“I quickly swerved toward the second German. But, evidently the pilot was so intent on downing the bomber, that he did not see me. I opened fire at about 50 yards. There was no way that I could miss. I was so close, in fact, that I almost crashed into him. The Fokker turned over on its back, and went into a spin. I watched him fall for a few moments, but then was interrupted by bullets whizzing past my head. Three Germans were after me. I fired at the closest plane—threw the Camel into a shallow dive—and raced to protect the damaged bomber.

“The Fokkers swarmed around us like maddened bees—shooting from below and behind. The air battle raged until we reached the coast, when the Germans finally broke off their attack.

“After landing at Dunkirk, I learned that I was only credited with one confirmed kill. Someone had reported that the second Fokker had pulled out of its spin. I was disappointed—to say the least.”

Flurry of Air Activity Ascends over the Western Front

The last week of September 1918 produced a flurry of air activity over the Western Front. The Camels of 213 Squadron were sent up two or three times a day on low-altitude missions in support of a coming Allied offensive between Ypres and the North Sea. The squadron was divided into three flights. David Ingalls narrated one mission on which he was a group leader: “We climbed rapidly through a clear break in the clouds and headed 10 miles out to sea. Then, after testing our guns, flew up the coast—keeping at 4000 feet, and just above the clouds. The trip seemed unusually long, but finally our flight commander turned toward land and we followed.

“My group’s assignment was to bomb a cluster of aviation workshops that had been built next to an aerodrome. The Germans did not spot us until we plunged out of the clouds. Antiaircraft fire was heavy, but it is difficult to hit a plane in an almost vertical dive. We pulled out at about 200 feet, and raced toward the junction of a canal and railroad track. Our target was just ahead and, like ducks in a row, impossible to miss.

“Fixing my aim on one of the shops, I pulled the lever dropping four 25-pound bombs. I looked up just in time to see the flight coming in above me drop its bombs late. I banked sharply to avoid being struck by one of the missiles. There were many direct hits by my group—while bombs from the planes above us dotted a vacant field with perfectly spaced little holes.

“By now, everyone was scurrying about the sky hunting for anything to shoot at. I had just opened fire on two lorries [trucks] parked near the shops, when bullets began zipping past my head. A nearby machine gun emplacement was empty. A moment later, I noticed Camels, from another group, climbing rapidly into the clouds, then diving and zooming across the aerodrome—and firing wildly in all directions. It was amazing that we did not shoot each other down.

“I circled the area one last time to assess the damage. Fires were still burning fiercely, and I signaled my group to head for home. Suddenly, we came under heavy antiaircraft fire. I quickly climbed to 1000 feet and dashed for a cloud bank. Then my engine almost cut out. It seemed that it was hitting on three cylinders at most. By the time I reached the clouds, the motor was running a little better—but it was still running rough.

“Upon reaching the coast, the sky cleared. I sighted one member of my group. We waved to each other and set a leisurely pace for home. Momentarily, I sighted a German two-seater drop from a cloud formation and head out to sea. He did not notice us. I edged in behind the enemy plane and opened fire. The surprised pilot immediately tried to reach Ostend. I chased him almost to the Ostend piers. Then one good burst and he caught fire. I banked sharply back out to sea—just in time to see the two-seater crash into the water.”

David Ingalls nursed his Camel’s temperamental engine safely back to Dunkirk. He learned that all of the planes in his group had returned, although two pilots had been slightly wounded. Reconnaissance photos, taken the next day, revealed that the raid was one of the most successful missions ever conducted by the 213 Squadron.

On September 22, Ingalls was assigned as flight leader of five Camels with orders to seek out and destroy enemy communications and supply lines. Ingalls and his group took off at daybreak, and raced across the Belgian countryside at treetop level. German aerodromes, ammunition trains, and army installations were the primary targets. Upon reaching Torhout, the flight attacked the town’s railway station and blasted a nearby supply center. On their return trip to Dunkirk, the Camels bombed a horse-drawn artillery convoy and machine-gunned the accompanying soldiers.

On the 24th, after only a day’s rest, David Ingalls and RAF pilot R. Hobson were sent out at 5 pm to hunt for a cunning German reconnaissance plane that had been photographing the Allied military buildup. Ingalls related the story of the mission, and his thrilling escape from death: “For quite some time we flew along the front at an altitude of 15,000 feet. It soon began to get dark, however, so we gave up the search and set a course for home. Moments later, I noticed antiaircraft fire ahead. Our batteries were shooting at an enemy plane that was flying over the Allied lines and hightailing it toward Ostend.

“I fired my guns to attract Hobson’s attention, then raced in pursuit. I was about a mile inland, between Nieuwpoort and Ostend, when I came within sight of an old Rumpler. The pilot was flying very slow. I dove under him and came up fast. But, I misjudged his speed and overshot the German. I threw my Camel into a dive to try again. This time, the crafty enemy pilot banked the plane to give his observer a perfect shot at me. I stayed beneath the Rumpler and made a wide circle to avoid the rear gunner’s bullets.

“I kept maneuvering for a good attack position. But, while making one turn, the observer nearly got me. He caught me in his sights—and fired a burst that ripped between the wing struts on my port side. I had flown so close to the Rumpler that I could make out the faces of the crew wearing their black helmets.

“After a few minutes of cautious dueling, I suddenly realized that the enemy pilot had decoyed me some distance behind German lines. I had to end the game quickly. I gave up the careful tactics—zoomed up on his tail and poured about a hundred rounds into the two-seater. A puff of smoke shot from the Rumpler and it burst into flames. I quickly threw the Camel into a steep dive to escape antiaircraft fire. Strategy dictated to try and reach the safety of the Allied lines by racing a couple of hundred feet above the ground. The dangers of flying this low, however, were from enemy planes above and gunfire below. The Germans had machine gun emplacements scattered about the countryside, specifically to shoot down low-flying aircraft.

“My Motor Stopped, and Gasoline Began Streaming out of the Tank”

“Only a short time had elapsed when I heard the rattle of a machine gun. My motor stopped, and gasoline began streaming out of the tank below my seat. I immediately switched on the gravity-feed tank and the engine started again.

“A tall tree line suddenly loomed in front of me. I pulled back on the stick. Fortunately the Camel is tail-heavy. The nose came up fast and I missed the trees by inches.

“The motor was running rough—only hitting on about six cylinders. I checked the rudder. It seemed to be working fine, but the ailerons answered weakly. More machine gun fire. I expected the rest of the controls to go any second. This was no time for trick flying. I sat perfectly still and, using the rudder, made short zigzag turns.

“It was a big relief when I finally crossed over our lines, and was quickly out of range from enemy gunfire. When I reached the aerodrome, I came in slowly over the trees. And, with a sputtering engine, managed to land safely.

“Hobson also returned. He had been flying behind and above me and attacked the pesky German machine gun batteries. Hobson confirmed my report that the Rumpler had crashed in flames. My plane was a total wreck. I was given a new Camel the next day.”

On September 28, 1918, British General Sir Douglas Haig began his fall offensive against the Germans in the Ypres Salient. Thousands of men and five hundred Allied aircraft were thrown into the battle.

David Ingalls described the 213 Squadron’s role in the massive assault: “In the early morning hours of the 28th, we took off on our first strike of the day. Our assignment was to fly low-altitude bombing and strafing missions behind enemy lines. It was miserable flying weather—rain and strong winds. The squadron climbed to 4000 feet, then gradually descended. We were at 300 feet when we crossed into German territory. The Allied artillery had created so much confusion in the attack sector that we were able to roam the countryside virtually unchallenged. Our bombs and machine guns methodically cut a tornado-like path of destruction throughout the area.

“As we neared Torhout—the enemy’s main road to the front—we spotted a long horse-drawn artillery train. Our squadron commander dived on the inviting target, and we followed. The execution of the attack was flawless—but horrible to watch. The German column was in a frenzy. Soldiers scattered for cover. Horses bolted, and the artillery pieces were pounded to junk as the frightened animals raced in all directions across the open fields. After our initial bombing run, we rapidly climbed for altitude—then dropped like angels of death upon the shattered remnants of the convoy.

“Sandwiched between the murderous attacks, there was one humorous incident. Our squadron commander was chasing a poor bloke who was riding a bicycle and legging it for dear life. The German suddenly hopped off the road and ducked behind a stone wall. When the commander circled around—and came in very low to see where his quarry had disappeared to—the fellow stood up and heaved a brick at his tormentor, ripping a large hole in the Camel’s wing. I doubt if our squadron leader will ever try that again. He had a tough enough time trying to explain the unusual damage to his aircraft. But, he was lucky that the German’s aim was bad—the brick could have struck the propeller.”

A War Record To Be Proud Of

On October 1, 1918, David Ingalls was relieved of combat duty and sent to England to organize a U.S. Naval Air Squadron. His war record in the skies over France and Belgium was enviable. In only six weeks, Ingalls had flown 109 hours in Sopwith Camels; made 63 flights over enemy lines; participated in 13 low-altitude bombing raids; engaged in 13 aerial combat actions; and shot down five German planes and one observation balloon. He was awarded the British Distinguished Flying Cross and the American Distinguished Service Medal.

After the war, Ingalls returned to Yale. He finished his studies in 1920 and graduated from the Harvard University Law School in 1923.

He became a member of the Ohio Legislature in 1926 and, in 1929, was appointed—by President Herbert Hoover—as Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Aviation. For a number of years he also personally flight-tested every plane adopted by the U.S. Navy.

At the outbreak of World War II, Ingalls returned to active duty. He served three years in the Pacific and was awarded the Legion of Merit and the Bronze Star. He retired from the Navy as a rear admiral in the U.S. Naval Reserve. David Ingalls died on April 29, 1985, at the age of 86.

Amazing! New to me. This is why I stick with this site.

Agreed, new to me also. One seriously impressive dude.