By Kevin Morrow

Robert Mors was in serious trouble. Immigration officials had stopped him for questioning upon his arrival at the port of Alexandria, Egypt, from Istanbul, and they immediately became suspicious. Great Britain and Germany were at war, and the British-controlled government of Egypt had begun expelling Germans from the country. So why was this man, an admitted German citizen, trying to get back in?

A search of Mors and his luggage yielded two boxes of dynamite blasting caps, a hand-drawn map of the nearby Suez Canal, and slips of paper with ciphered messages. They clearly had nabbed a spy and saboteur.

British intelligence had been observing ominous movements of fighters and agitators across the Middle East for weeks, suspecting that the neutral Turks were plotting to enter the war on Germany’s side. Additionally, there was already underway a campaign of bombings and guerrilla attacks accompanied by propaganda designed to foment revolt in Egypt. These events constituted the opening salvos of a looming invasion.

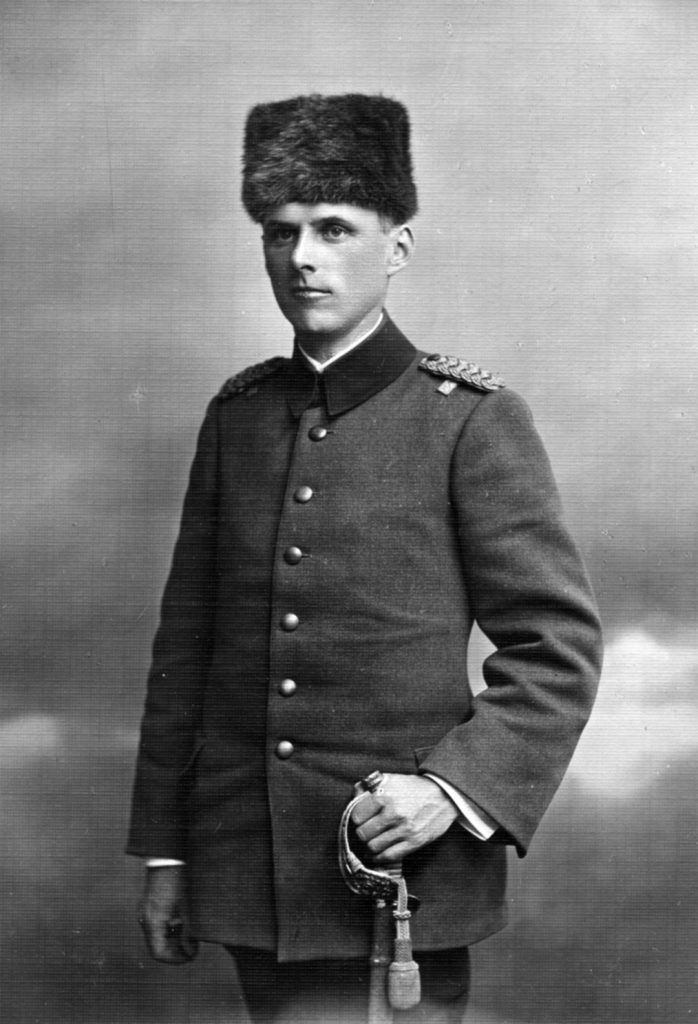

Mors exposed several key figures behind the plots underway in Istanbul during his interrogation. One of these involved his handler, Curt Prufer, an Arabic scholar who had served as a diplomat at Germany’s consulate in Cairo before the war. In his official capacity, Prufer handled interpretation and translation services for the consulate. But, unofficially, he moonlighted as an agent provocateur. Specifically, he incited Egyptian nationalists and Islamists against Britain through clandestine rabble-rousing meetings, interviews in the Egyptian press, and even an anti-British preaching tour among Bedouin sheikhs in Syria and Egypt.

Prufer’s subversion tactics borrowed a page from the Muslim holy war tactic embraced a generation earlier by German foreign policy adventurists who designed the approach as a victory strategy for the coming European conflict. They believed that if they incited Muslims in rival European empires to revolt, then the Muslims would defect to the Ottoman Empire, the standard bearer of global Islam. Fighting alongside the Turks as allies, Germany could then destroy enemy forces diverted from Europe to put the fires out, win the war, and gain a greatly expanded Middle East empire.

When the holy war strategy became official German policy after the outbreak of fighting in August 1914, Prufer immediately volunteered his special skills to the German Foreign Office, promising to incite unrest in Egypt. On August 28 he was bound for Istanbul to run Germany’s espionage, propaganda, and sabotage operations in Ottoman territory alongside his new Turkish allies.

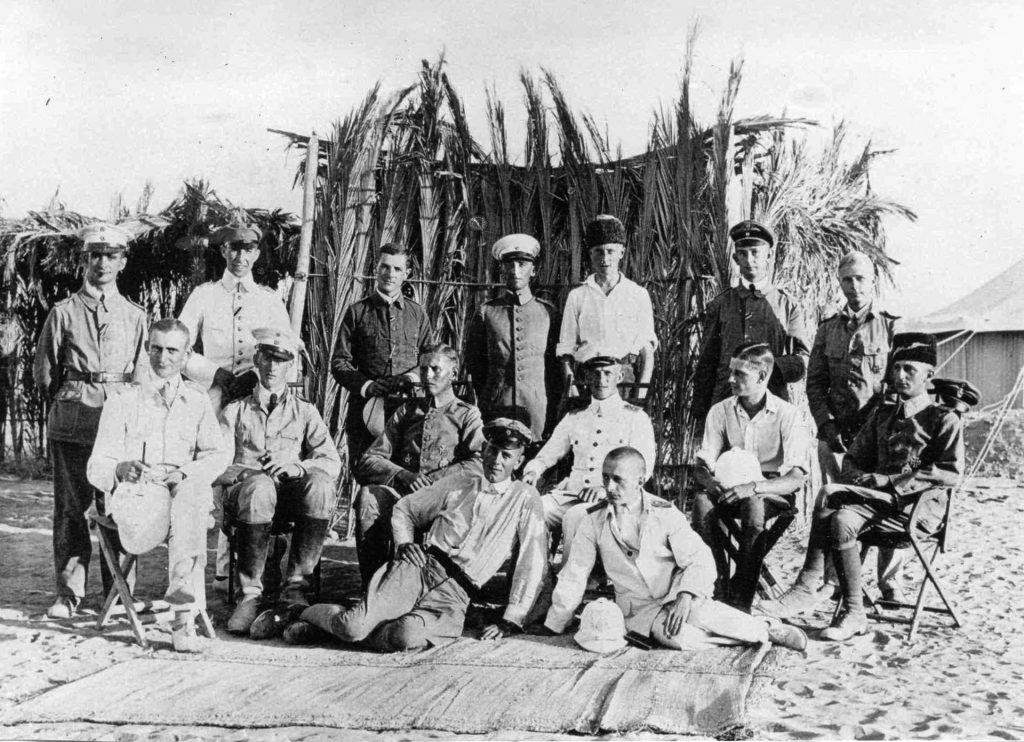

No effective German covert activities organization existed in the region, so Prufer had to create a concept from scratch using locally available Egyptian and German expatriates, local Arabs, and Ottoman paramilitary forces. During two frenetically busy weeks in Istanbul, Prufer labored ceaselessly to organize and equip them with German cash, guns, and propaganda materials and to spur them into action using his considerable powers of persuasion.

The covert operations chief left Istanbul on September 20 for a tour of Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine to enlist pro-Turkish, urban Arab elites in the Ottoman war effort as media propagandists and roving holy war recruiters. Meanwhile, the first agents of Prufer’s new spy ring began volunteering for intelligence-gathering duty in Egypt and Sinai. These were mostly Arab men whose livelihoods allowed substantial freedom of movement that provided perfect cover for their activities, such as the Palestinian mufti of Haifa Sheikh Muhammad Murad, Damascus camel merchant Muhammad al Bassam, and railway mechanic ‘Abd al Hamid Yusuf.

Over the next three months, the Prufer ring assembled an incredibly detailed picture of British fortifications, troop strengths, and weapons in Egypt and at the Suez Canal. Though Prufer himself became dissatisfied with his agents’ performance, their intelligence misfires hardly surpassed those of British intelligence in Cairo, which frequently had to fly blind during the war’s early months.

Even as he was sending spies to infiltrate Egypt and Sinai, Prufer was closely monitoring the loyalties of his Arab collaborators, some of whom were suspected as enemy spies or clandestine Arab nationalists. Prufer’s Turkish superiors worried most of all about the shaky loyalties of the stubbornly independent-minded Bedouin chieftains inside Arabia, as the Turks anxiously desired the participation of leaders from the birthplace of Islam in the holy war. Prufer devoted special attention to keeping tabs on the most prominent Arabian sheikhs through his informants in the camel trade.

Of Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the emir of Mecca and future leader of the Arab Revolt, Prufer reported on November 3 that he “is English through and through, but luckily powerless and in our hand. An encroachment of [future Saudi king] Ibn Sa’ud on Medina is unlikely. All the same, Ibn Rashid is so thoroughly preoccupied with him that he is no longer worth considering for our expedition.”

Throughout the autumn of 1914, the Turks had dragged their feet in entering the war. But on October 29 they allowed a German-led surprise naval attack on Russian ships and shore facilities in the Black Sea. The war in the Middle East had officially begun.

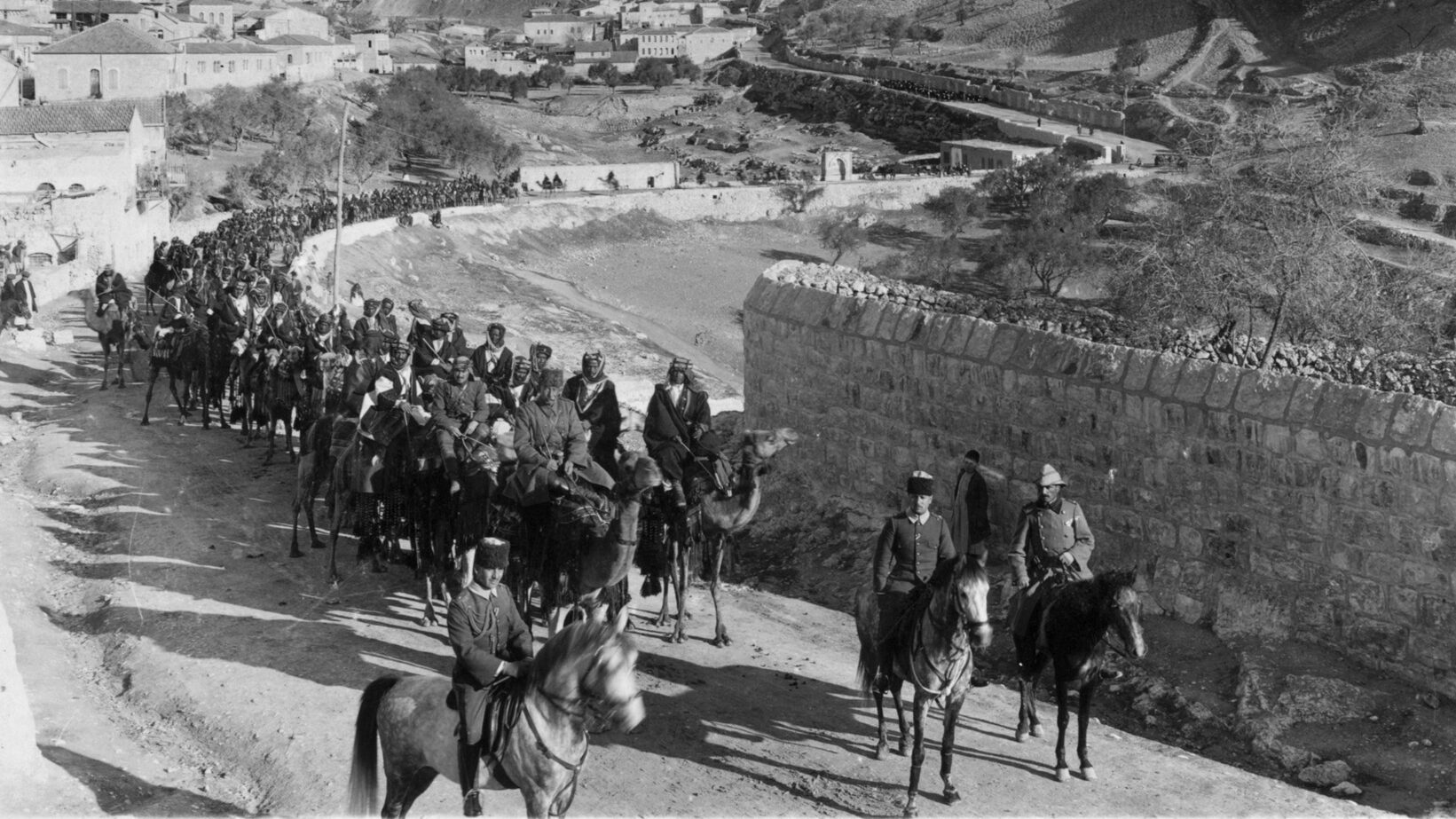

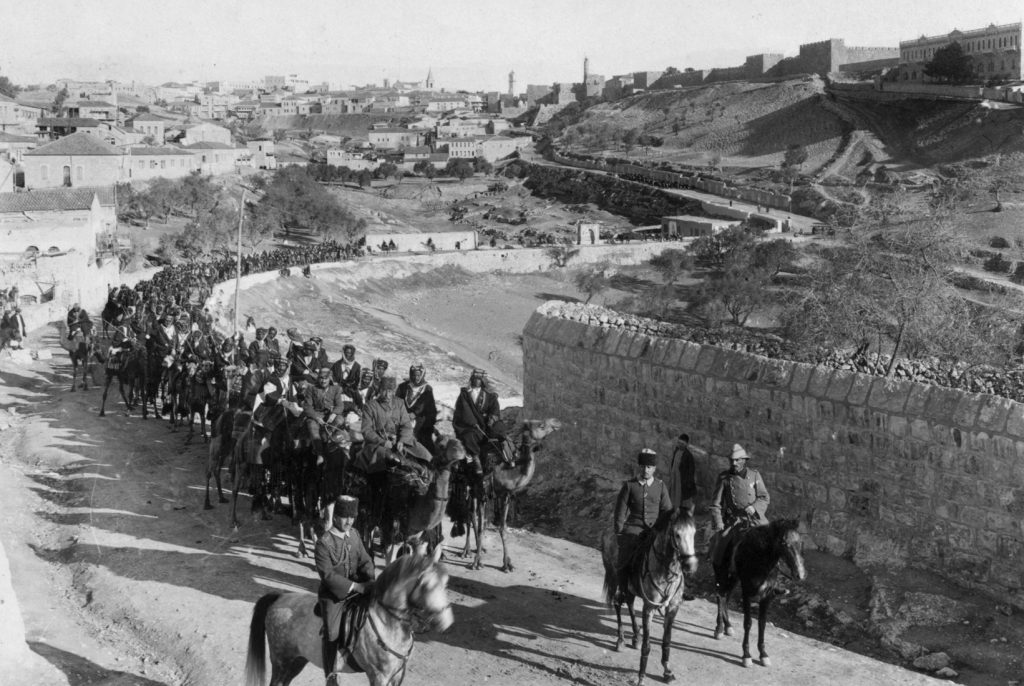

Two and a half months later, a 17,000-man Ottoman attack force stood fully assembled at a camp near Beersheba in southern Palestine, ready to push off for the first major military campaign in the Middle East, the attack on Egypt. At midnight on January 13, 1915, the army headed west into the Sinai desert. Prufer, who had finished his preparations by then, departed with the army.

The Ottoman army endured rain, sandstorms, bitter cold nights, boredom, and weariness for 17 days. Their travails occasionally were relieved by halts at staging camps throughout the Sinai. Prufer’s sector was quiet until an enemy airplane bombed his camp on January 26. The incident was Prufer’s first taste of combat. “I confess that the hammering of the bombs, the powerful explosion and the black billowing smoke somewhat scared me, although I did my best to hide it,” he wrote.

Far worse things awaited the Turkish army at the Suez Canal where 30,000 British and Commonwealth troops had dug in along a 100-mile front, shielded by fortified posts, trenches, and armored trains equipped with artillery. Most ominous were the battle cruisers that controlled the flat, coverless terrain east of the canal. “Seems to me to be a disaster,” Prufer wrote on January 30. “We will be destroyed before we have actually come in the vicinity of the canal.”

When troops began dragging their pontoon boats toward the canal to force a crossing in the predawn darkness of February 3, enemy machine-gun fire riddled and sank many of the boats, forcing the attackers to retreat. British forces repelled a second crossing attempt at dawn spearheaded by infantry attacks against shore outposts and an artillery duel with the warships.

Prufer and a column of engineers waited impatiently all day long for the signal to commence blocking the canal with sandbags after the army had crossed. The signal never came. The attack failed, so the next morning an orderly retreat back to Palestine began. Prufer rushed back toward Jerusalem on camelback, stopping February 9 at Hafir al Awja on the Palestine-Sinai border to hammer out two after-action reports.

His report to Hans von Wangenheim, the German ambassador in Istanbul, dispassionately catalogued the expedition’s failings. The Turks suffered from poor water, meager provisions, and a lack of long-range artillery pieces and aviators. Moreover, their camels were dying at an alarming rate from fatigue. The Arab spies that Prufer had sent into Sinai and Egypt were “cowardly, and as civilians, mostly unreliable in their reports, because they were not able to clearly see the military situation correctly,” he wrote. Efforts to incite a holy war produced neither battlefield defections nor a revolt in Egypt. “Although the Turkish losses are heavy, the talk cannot be of a catastrophe, nor of a defeat, by any means,” he concluded. The expedition actually was intended as a reconnaissance in force.

Prufer’s report to Max von Oppenheim, his former mentor in Cairo, was even more blunt. The Egyptians were cowards and lacking in patriotism, while the Syrians and Palestinians were essentially useless owing to traditional Arab-Turk enmity. “The holy war is a tragicomedy,” and all the Arabian and Levantine Bedouins, Kurds, and Druze either quit the battle prematurely, deserted, or stayed behind in Palestine.

Planning for a second canal attack began immediately after the debacle in February. Prufer seized the opportunity to reinvent his intelligence organization by replacing his Arab agents with Jews from Palestine. On April 8 Prufer dispatched three new spies from his base of operations in Jerusalem to Egypt under the cover of false identities. Collectively, they gleaned a wealth of information, including interesting reports of Anglo-Egyptian tensions and discipline problems with Australian and New Zealand troops, who rioted in Cairo in April.

Although Prufer’s agents were spying in Egypt, Turkish counterintelligence uncovered an Arab nationalist plot to revolt against the Ottoman government. The consequent hanging of 11 suspects in Beirut on August 21 greatly enraged Ottoman Arabs and sorely tested their loyalties. In November Ahmet Djemal Pasha, the Ottoman governor of the Arab provinces, sent Prufer to Haifa, Damascus, and Beirut to gauge whether the anti-Turkish mood among Jews and Arabs merited special surveillance. Although Prufer found tremendous Anglo-French sympathy among Jews and Arab Christians, he believed it presented minimal danger to national security. The predominantly Muslim Arab nationalist movement, owing to just and severe measures of the government, was weakened, while most other Muslims supported the government. He therefore believed that new police measures were unnecessary.

In May 1916 Prufer unexpectedly quit his post as intelligence chief. Disgruntled over disputes with Djemal and a conviction that “the intelligence system [was] being run almost exclusively by the Turks,” Prufer enlisted as an observer with Flight Detachment 300, the German air group based in Beersheba. By joining he sought to collect intelligence not just from the ground, but also from the air.

In his first flight on May 5, Prufer narrowly escaped a crash landing. Undeterred, he quickly settled into a routine of flight and weapons training, bombing attacks, and reconnaissance flights over Egypt and Sinai.

On June 9 the airmen received some electrifying news that potentially might alter the shape of the war in the Middle East. They learned that Sharif Hussein had revolted against the Turks. “The revolt in the Hijaz is intensifying,” wrote Prufer, who noted that he had warned German officials about the sheikh.

Momentous as this fire in the Ottoman rear became in subsequent months, the main action in mid-1916 still remained the imminent attack on the Suez Canal. It aimed at seizing Britain’s forward-most defenses in Sinai, which were the fortifications at the village of Romani near the Mediterranean coast, as a forward artillery position for bombarding shipping in the nearby canal.

Logistical headaches and troop redeployments to other fronts had repeatedly delayed this second attack, but everything was ready by late July. Once again, a Turco-Germanic force trekked into the Sinai Desert to take on the British army known as the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, or EEF.

The first infantry assaults on EEF defenses came before dawn on August 4. For several hours, the Turks slowly pushed the enemy back with infantry attacks and accurate artillery fire, while Prufer and his fellow airmen bombed enemy encampments near Romani. Despite these attacks from air and ground forces, the EEF doggedly held the line throughout the day. Deep desert sand, brutal summer heat, and a stream of enemy reinforcements eventually wore the attackers down, and by early the next day, the expeditionary force was retreating, pursued by mounted enemy troops.

Britain’s victory at Romani proved to be the decisive turning point in the Middle East war. The threat to Egypt was destroyed, and the EEF advance now turned eastwards toward the heart of Ottoman territory.

The clash at Romani also ended Prufer’s combat service. Exhausted and sick after two years of constant action, he returned to Berlin, where he was promoted to lead the Istanbul branch of the News Bureau for the Orient, the German Foreign Office’s official disseminator of holy war propaganda.

The Foreign Office had by then abandoned its propaganda’s shrill Islamist tone and adopted a new, nongovernmental front organization called the German Overseas Service to cloak its propaganda activities. Despite the changes, Germany’s messaging efforts in the Middle East were languishing.

For months following his return to Istanbul in late March 1917, Prufer fought a losing battle to procure subject-appropriate materials for Turkey and to lift censorship springing from Turkish resentment of German activity in Muslim lands. He also repeatedly urged switching the focus from the overabundant praise of the German war effort and what he termed “weepy accusations” against the enemy to Germany’s peaceful activities, which he hoped would build affection in the Middle East for Germany similar to that enjoyed by France before the war.

As Prufer’s propaganda effort muddled its way forward, the EEF offensive, which had stalled in southern Palestine, roared to life again, overrunning Beersheba and Jerusalem by the close of 1917. Prufer’s zone of operations had begun to steadily shrink, so the Foreign Office assigned him a new mission as government minder for Khedive Abbas Hilmi II, the former ruler of Egypt. The khedive had been banned from Egypt and deposed by the British after publicly throwing in his lot with the Turks in 1914. Three years of cajoling the British, Germans, and Turks to support his return to the throne had failed, but concerns about enemy influences on his loyalties induced the Turks to invite the khedive to move to Istanbul in October 1917. The Germans assented to this in the hope that they could retain the khedive as a future client ruler in an Egypt under German or Turkish control.

To burnish his relations with Germany, Abbas Hilmi toured Germany and Belgium meeting with government dignitaries throughout July and August 1918. The likelihood of a German defeat in Europe had by then begun to dawn on the khedivial party, despite the outside appearance of normalcy. In June Prufer was still repeating happy talk regarding what he described as “open rumors about a special peace for Turkey.” By the time the Allies launched their Hundred Days Offensive in France in August, he pronounced the “entire world very depressed,” a despondency the khedive’s entourage attempted to dispel with “boozing, dancing, and flirting, hectic room parties and the like,” wrote Prufer. Clearly, the end was drawing near.

Bulgaria’s surrender on September 30 and the liberation of Damascus on October 1 spelled what the Turks realized was certain defeat. A month later they surrendered to the British at Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos. Germany itself surrendered in France on November 11.

The Germans’ holy war strategy had flopped. Islamic propaganda manufactured by Christian foreigners to promote German and Turkish domination failed to rally the global Muslim community to the Ottoman flag, while the Turks had proved too weak to play the role of the standard bearer of global jihad assigned to them.

The British and the French, by contrast, had beaten the Germans and Turks at their own game by publicly offering independent nationhood to willing Ottoman defectors. Once the Turks were defeated, though, the British and French reneged on their promises to their Arab partners by seizing the liberated Ottoman Arab provinces for themselves as spoils of war. As a result, riots and insurrections broke out across the Arab world in protest against the European imperialists’ cynical thwarting of self-rule, metastasizing into a perpetual cycle of violence, terrorism, and war that drove out the British and French after 1945.

Although the urge to dominate foreigners for national benefit burned German, British, and French hands alike before and after 1918, Prufer did not learn the lesson. During World War II Prufer once again willingly served a belligerent, expansionist German government as its ambassador to Brazil. As before, German aggression resulted in defeat and ruin.