By Don Hollway

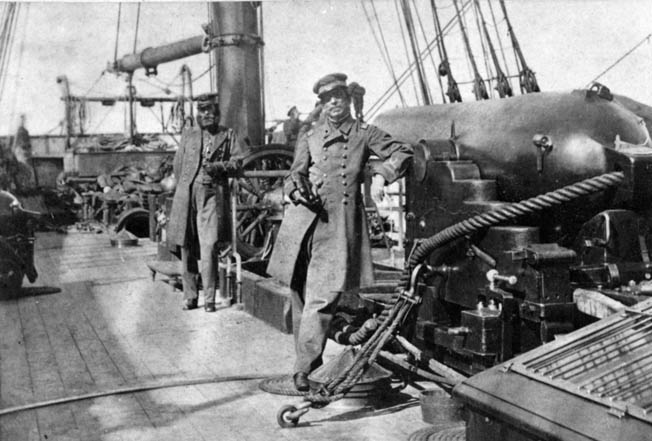

On August 24, 1862, newly promoted Captain Raphael Semmes of the Confederate States Navy called his largely English crew to the quarterdeck of his new command, the 220-foot battle cruiser Alabama, lying off the coast of Terceira in the Azores. A band played “Dixie” as Semmes read aloud his commission from President Jefferson Davis and the Stars and Bars were run up the mainmast. “Now, my lads, there is the ship,” said the captain. “She is as fine a vessel as ever floated. There is a chance that seldom offers itself to a British seaman, that is, to make a little money. We are going to burn, sink and destroy the commerce of the United States. Your prize money will be divided proportionately. Any of you that thinks he cannot stand to his gun, I do not want.”

“The Alabama Will be a Fine Ship”

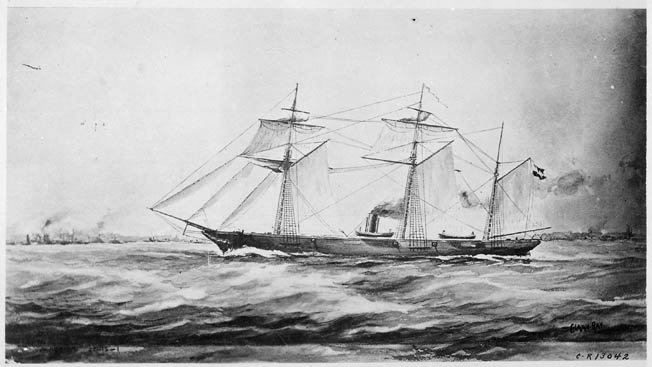

Covertly financed through the sale of Southern cotton and built at the famous Laird Shipyard on the Mersey River near Liverpool, Alabama was a wood-hulled, bark-rigged (foremasts rigged square, mizzenmast fore and aft), 220-foot sloop of 1,050 tons. With two 300-horsepower steam engines driving a single two-bladed screw, she could make 13 knots. “She was a perfect steamer and a perfect sailing ship, at the same time,” marveled Semmes. “The Alabama was so constructed, that in fifteen minutes, her propeller could be detached from the shaft, and lifted in a well contrived for the purpose, sufficiently high out of the water, not to be an impediment to her speed. When this was done, and her sails spread, she was, to all intents and purposes, a sailing ship. On the other hand, when I desired to use her as a steamer, I had only to start the fires, lower the propeller, and if the wind was adverse, brace her yards to the wind, and the conversion was complete.”

Unlike a Napoleonic-era man-of-war, which mounted more than 50 guns per side, Alabama totaled just eight. Her six 6.4-inch, 32-pounder smoothbores were dwarfed by her two main guns. Designed by Captain Theophilus Alexander Blakely of the British Army, with cast iron barrels and breeches wrapped in wrought iron or steel bands, they were so heavy that they had to be mounted directly amidships for proper sea keeping and manhandled on a complex system of pivots and tracks to one side or the other prior to battle. The aft 8-inch smoothbore fired a 68-pound shot or 42-pound shell; the forward 7-inch rifle fired a longer 100-pound shot or 85-pound shell.

Alabama’s executive officer, Lieutenant John McIntosh Kell, had signed 80 new hands to join the veteran sailors of Semmes’ previous command, the cruiser Sumter. “The Alabama will be a fine ship, quite equal to encounter any of the enemy’s steam-sloops,” their captain recorded in his log, “and I shall feel much more independent in her, upon the high seas, than I did in the little Sumter.”

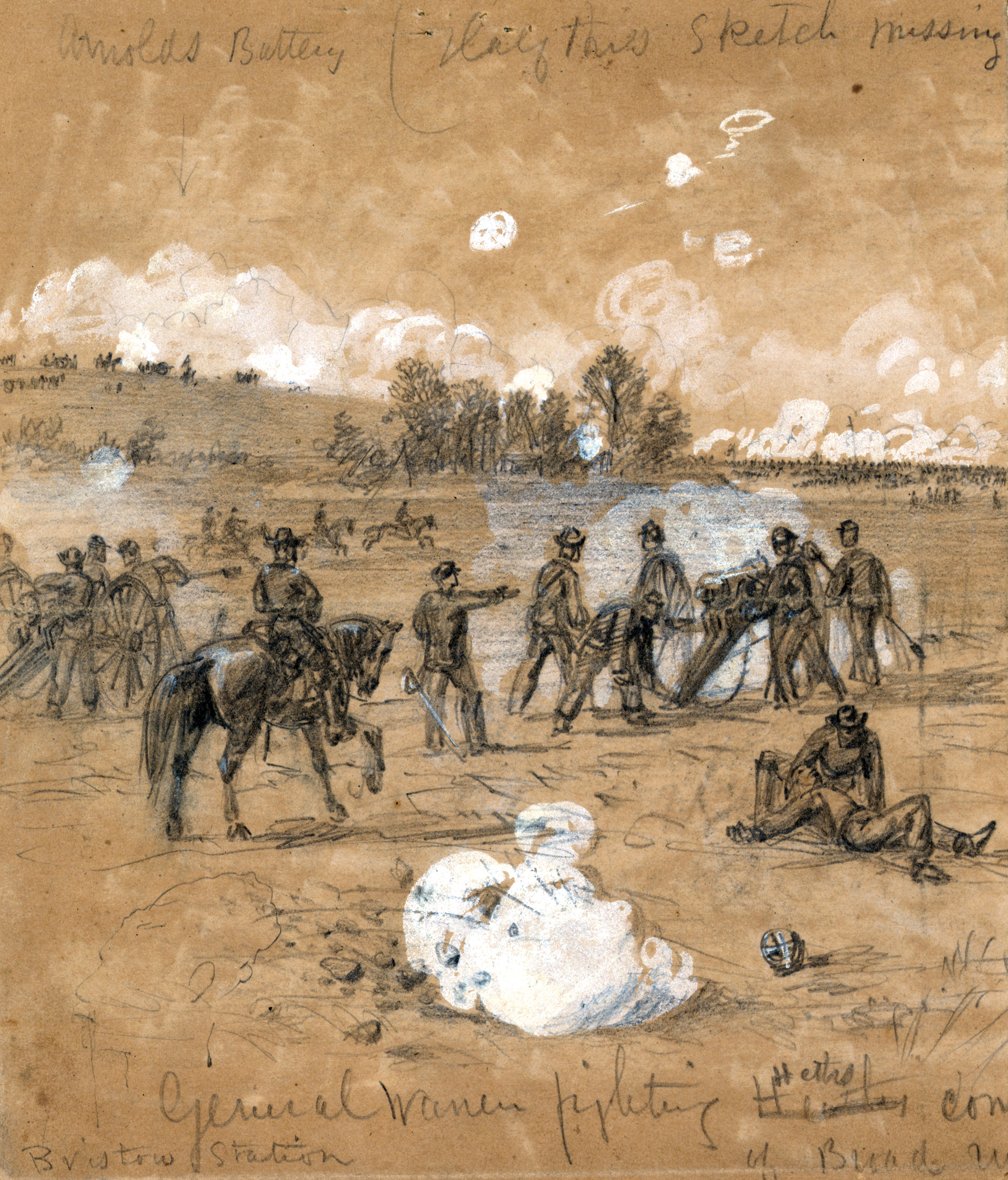

John Winslow: Commander of the Kearsage

While Semmes sailed off to seek glory, a former fellow officer was languishing in the backwaters of the naval war. In 1861, Commander John A. Winslow, a North Carolina-born Unionist, had been assigned to the Western Gunboat Flotilla at Cincinnati, intended to sail down the Ohio and wrest control of the Mississippi. He had not been confident of the outcome: “Our [ironclad] gunboats are heavy. It is doubtful whether we can get down the river, on account of the draft of water, without first taking out the guns.”

On his first venture downstream, commanding the flagship Benton, she grounded on a sandbar 30 miles south of St. Louis. As Winslow attempted to winch her off, a link of chain parted with such force that one shard flew 500 feet; another struck him in the left arm, tearing away much of the muscle. “It was a great mercy that the bolt did not strike me on the body,” he wrote home, “as it would have made an end of me.”

Sent home to recuperate, Winslow did not return to duty until the summer of 1862. He was promoted to captain that July and might even have expected command of the flotilla but was passed over, possibly due to his increasingly dim view of superiors up to and including President Abraham Lincoln, whom he considered insufficiently abolitionist in his sentiments. After the Union defeat at Second Bull Run that August, Winslow injudiciously told a reporter for the Baltimore American, “I’m glad of it. I wish the Rebs would bag Old Abe, too. Until something drastic is done to arouse Washington we shall have no fixed policy.”

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles narrowly declined to prosecute Winslow for insubordination or treason, but at the end of October he wrote to him: “You are hereby detached from the Mississippi Squadron and placed on furlough. You will regard yourself as awaiting orders.” Winslow was bedridden with malaria and an inflammation of his right eye (in which he would eventually lose sight) when Welles found a suitably out of the way command for him: the sloop of war, USS Kearsarge.

Cabin Mates in the Mexican-American War

Alabama had been wreaking havoc among the Atlantic whaling fleet, taking 20 prizes up and down the Eastern Seaboard from Newfoundland to Bermuda. Among them, captured and burned on September 9, was the whaling bark Alert, made famous in the 1840 memoir Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana, Jr. Kearsarge was an even match for her, and Winslow for Semmes as well. The two captains not only knew each other, they had briefly even been cabin mates.

In 1846, as young lieutenants during the Mexican War, each had assumed his first command. Winslow lost his captured Mexican sloop, renamed USS Morris, on a reef in a storm, and Semmes lost his brig, Somers, in a sudden squall while chasing a Mexican blockade runner. Both officers were completely exonerated but spent time together in the doghouse aboard the American flagship Cumberland. “It is a joke now,” Winslow wrote, “so I frequently say, ‘Captain Semmes, they are going to send you out to learn to take care of ships in blockade,’ to which he replies, ‘Captain Winslow, they are going to send you out to learn the bearing of reefs.’” Each was promoted to commander in 1855. In December 1860, Winslow’s appointment as Inspector of the 2nd Lighthouse District was signed by Semmes, as Secretary of the U.S. Navy Lighthouse Board. The next month, however, the country sundered and the old friends took opposite sides.

A Late Arrival at Galveston

In December 1862, Winslow shipped out from New York to rendezvous with Kearsarge. In the windward passage between Cuba and Hispaniola, Alabama ran down the sidewheel steamer Ariel, carrying 140 United States Marines and all their gear. The Confederates reaped 124 muskets, 16 swords, and $10,000 in Federal cash—Alabama’s largest single haul of the war—and only released their prey under a $261,000 bond (worth $3.8 million today) payable on demand when the Confederacy won the war. Even more importantly, Ariel’s cache of New York newspapers, less than a week old, announced that a 30,000-man army under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks had sailed to invade Texas at Galveston.

“To transport such an army, a large number of transport ships would be required,” Semmes reasoned. “As there were but twelve feet of water on the Galveston bar, very few of these transport ships would be able to enter the harbor; the great mass of them, numbering, perhaps, a hundred and more, would be obliged to anchor, pell-mell, in the open sea. Much disorder, and confusion would necessarily attend the landing of so many troops, encumbered by horses, artillery, baggage-wagons, and stores. My design was to surprise this fleet by a night-attack, and if possible destroy it, or at least greatly cripple it. Half an hour would suffice for my purpose of setting fire to the fleet, and it would take the [Union] gun-boats half an hour to get up steam, and their anchors, and pursue me.”

His information wasn’t quite fresh enough, however. By the time Alabama reached Galveston at dusk on January 11, the Texans already had repelled the assault. Banks’ army disembarked at New Orleans. Instead of a fleet of helpless troop ships, Alabama’s lookout spotted only a few Union warships maintaining a sullen blockade. “I certainly had not come all the way into the Gulf of Mexico, to fight five ships of war, the least of which was probably my equal,” Semmes wrote. “Whilst I was pondering the difficulty, the enemy himself, happily, came to my relief; for pretty soon the look-out again called from aloft, and said, ‘One of the steamers, sir, is coming out in chase of us.’”

Luring the Hatteras

The 1,100-ton converted passenger ferry USS Hatteras had taken Alabama for a hapless blockade runner and churned out after her alone. “She was evidently a large steamer,” Semmes wrote of Hatteras, “but we knew from her build and rig, that she belonged neither to the class of old steam frigates, or that of the new sloops, and we were quite willing to try our strength with any of the other classes.”

Easily capable of outrunning the iron-hulled sidewheeler, Semmes shortened sail and let the Federals slowly gain, all the while luring them ever farther out to sea. Some 20 miles later, under cover of dusk, he took in his sails, made ready his guns, and came about to await his would-be captor. Union Lt. Cmdr. Homer C. Blake, for his part, was beginning to think something amiss. Presenting his own broadside, such as it was—a mere pair of 32-pounders and two even smaller rifled guns—he called across the water, “What ship is that?”

The Confederates replied, “This is her Britannic Majesty’s steamer Petrel.”

“If you please, I will send a boat on board of you.”

“Certainly, we shall be happy to receive your boat,” Semmes answered. As the Union boarding crew put down to row across, he turned to Lieutenant Kell. “I suppose you are all ready for action?”

“We are,” said Kell. “The men are eager to begin, and only awaiting your word.”

Semmes gave it. Kell stood up and shouted through his bullhorn, “This is the Confederate States steamer Alabama!” and the raider let fly a full broadside.

The crew of Hatteras, having smelled trouble, answered immediately. The men in the cutter ducked as shot and shell flew low overhead in both directions. Giving throttle, the two warships conducted a running gunfight at ranges right down to 25 yards, so close their crews traded shots with muskets and revolvers. Several shells from Hatteras went through Semmes’ cabin, and one passed narrowly over his head on the quarterdeck, but none struck below the waterline. The battle could only end one way. “The action was very sharp and exciting while it lasted, which was not very long,” wrote Semmes, “for in just thirteen minutes after firing the first gun, the enemy hoisted a light and fired an off-gun, as a signal that he had been beaten. We at once withheld our fire, and such a cheer went up from the brazen throats of my fellows, as must have astonished even a Texan, if he had heard it.”

The men of the Galveston fleet did hear, if not the cheers of the Southerners, the reports of their big pivot guns and, seeing their flashes on the horizon, realized Hatteras had blundered into a fight. Raising anchor and steaming out in all haste to assist, they passed the little cutter—its crew, as might be imagined, stroking with all their might for shore—but found no trace of Alabama. “As soon as the action was over, and I had seen the [Hatteras] sink,” wrote Semmes, “I caused all lights to be extinguished on board my ship, and shaped my course again for the passage of Yucatan.” In the morning the Federals found Hatteras resting on the shallow bottom of the Gulf with a pennant still flying from the tip of her mainmast, a few feet above the waves.

Making the Kearsarge an Ironclad

Meanwhile, Winslow was stuck in the Azores all spring. “The Kearsarge has been in [dry] dock, repairing at Cadiz, long enough to have built a vessel in the United States,” he groused, “and I am not aware that she has yet got out.” By the time he took delivery in April, he had formulated grand plans. Kearsarge’s armament would hold no great advantage over Alabama. She mounted only four 32-pounders, although her two pivot guns were larger than Semmes’: two 11-inch smoothbores designed by Captain John Dahlgren of the Navy Ordnance Department. Made of cast iron pieces weighing nearly eight tons apiece, each could fire a 166-pound shot or 133-pound explosive shell 2,300 yards, through four inches of steel and 20 inches of oak.

Winslow’s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. James S. Thornton, knew how to turn their wood-hulled sloop into an ironclad. “We remained ten days plating our vessel for some thirty feet each side, to protect our machinery,” Winslow wrote. “This plating consists of our heavy [spare anchor] chains, suspended close together, which are hung to the sides of the vessel, and makes a complete armor for protection against shot, etc.” Disguised with a wooden veneer, from any distance the chain cladding was nearly invisible.

The Confederate’s South Atlantic Squadron

Meanwhile, Alabama had ranged down the coast of South America on what would be her most lucrative raid. Preying on merchant traffic coming up from Cape Horn, Semmes had captured or burned 19 vessels, sometimes at the rate of two or three a day. By mid-May, when Winslow was finishing up his armor in the Azores, Alabama was carrying no less than four ships’ crews prisoner. She stopped off in Bahia, Brazil, to put them ashore and take on coal, and by complete coincidence met Georgia, fresh from Ushant on her maiden raid, and her own sister ship, Florida, just up the coast at Pernambuco. The Confederates had formed an inadvertent South Atlantic Squadron.

The three raiders were on separate missions and soon parted company, but the possibilities must have been plain to Semmes. Capturing seven more ships in the South Atlantic by the beginning of June, he transferred spare crewmen and a pair of captured cannons to the 350-ton bark USS Conrad and rechristened her as the raider CSS Tuscaloosa. “Never, perhaps, was a ship of war fitted out so promptly before,” he recounted proudly. “The Conrad was a commissioned ship, with armament, crew, and provisions on board, flying her pennant, and with sailing orders signed, sealed, and delivered, before sunset on the day of her capture.” The Confederate high seas raiders were beginning to reproduce.

By the time she reached Cape Town, South Africa, in August 1863, Alabama was an international sensation. “Three hearty cheers were given for Captain Semmes and his gallant privateer,” declared the Cape Town Argus. “It was not, perhaps, taking the view of either side, Federal or Confederate, but in admiration of the skill, pluck, and daring of the Alabama, her captain, and her crew, who afford a general theme of admiration for the world all over.”

Heading For England and France

News from home, however, was nothing but bad. Gettysburg and Vicksburg were lost. The Mississippi River was under Federal control from the Ohio River to the Gulf of Mexico. “As for ourselves, we were doing the best we could, with our limited means, to harass and cripple the enemy’s commerce, that important sinew of war,” Semmes wrote, “but the enemy seemed resolved to let his commerce go, rather than forego his purpose of subjugating us.”

Loath to be trapped in harbor again and guessing the U.S. Navy would await him in the shipping lanes toward Madagascar, he set out due east. With southern midwinter gales at her back, Alabama covered over 2,800 miles in two weeks, turning up northwest of Australia toward the East Indies. Her reputation preceded her. American ships either stayed in harbor waiting for the Confederates to vacate the area or signed themselves over to neutral nations, beyond capture. Alabama ranged as far as Singapore and Vietnam, but through year’s end took only six vessels.

“My intention now was to make the best of my way to England or France,” Semmes decided, “for the purpose of docking and thoroughly overhauling and repairing my ship.” In that era few vessels could go a year and a half without putting in for a complete overhaul, but Alabama had never seen so much as a dry dock, let alone a home port. Her beams were splitting, her decks were sagging, her boilers were corroded with salt water, and her bottom was dragging barnacles, seaweed, and copper plating. Semmes logged, “Shall we ever reach that dear home which we left three years ago [aboard Sumter], and which we have yearned after so frequently since? Will it be battle, or shipwreck, or both, or neither? And when we reach the North Atlantic, will it still be war, or peace? When will the demon-like passions of the North be stilled?”

“The English All Hate This Ship”

Winslow and Kearsarge spent the winter attempting to single-handedly blockade England, Ireland, France, and Spain. They left Florida in dry dock at Brest, France, trying to catch Georgia at Queenstown, Ireland, but Georgia put in at Cherbourg instead. Winslow gained nothing but 16 Irishmen who joined his crew. When Her Majesty’s Foreign Office got wind of it, he was accused of signing them in violation of the Foreign Enlistment Act, which forbade her subjects from equipping or manning foreign ships of war (despite which Semmes’ crew was mostly British). “The English all hate this ship,” Winslow wrote, “and took bold of this act to try and make something out of it. This thing has cost me more writing than would fill a quire of paper.”

By April he was being charged in the House of Lords with violating British neutrality. He answered in the press, referring to the Irishmen as “miserable trash,” accusing the British of questionable motives, and generally offending everyone involved. England and France both forbade Kearsarge to anchor within their ports for more than 24 hours at a time, and a full report on the incident was submitted to Washington. Winslow’s career prospects were not improved by his complete inability to capture, destroy, or even detain a single enemy ship; while he was distracted with legalities, in February both Confederate raiders escaped harbor. “If we had more ships here,” wrote the near disgraced captain, “we certainly could have got the Georgia or Florida.”

The Alabama Chooses to Fight

Semmes found no warmer welcome. In 1862, when victory had seemed within the South’s grasp, the European powers had been sympathetic, even encouraging, to the Confederacy. In 1864 they were no longer eager to defy the Union. Arriving at Cherbourg on June 12, Alabama was to be permitted to repair or coal, but not both, and she was to be on her way as soon as possible. On June 14, Kearsarge suddenly appeared outside the Cherbourg breakwater.

Semmes and Kell talked over their options, which were few. They could remain in port, in which case Federal cruisers would flock to Winslow’s aid and see to it that Alabama rotted at anchor, or they could fight. If they were defeated, the outcome for the Confederacy would be the same: one ship lost. A victory, on the other hand, would not only be momentous for Semmes and his crew, who might turn Kearsarge into a fresh new raider; for the Confederacy it would be a public relations coup that might even sway the European powers back to her side.

Historians have debated whether Semmes was aware of the Union sloop’s chain cladding; in his memoirs he claimed to have learned of it only after the fact, though it seems to have been common knowledge aboard his ship. He may simply have discounted its existence as rumor or decided that it made no difference. For Alabama, to deny battle was tantamount to defeat. “The combat will no doubt be contested and obstinate,” Semmes wrote, “but the two ships are so equally matched that I do not feel at liberty to decline it. God defend the right, and have mercy upon the souls of those who fall, as many of us must.” Accordingly, he sent word through channels: “I desire to say to the U.S. consul that my intention is to fight the Kearsarge as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements. I hope these will not detain me more than until tomorrow evening, or after the morrow morning at furthest. I beg she will not depart before I am ready to go out.”

Choosing coal over repairs, he packed the bunkers around his ship’s machinery with an extra 150 tons of hard Welsh anthracite as his own kind of armor. He sent ashore five bags of gold sovereigns, about $5,000 each, bonds from his surviving victims, and a collection of ships’ chronometers taken from the rest. Meanwhile, Kearsarge prowled back and forth outside the breakwater, Winslow running gun drills and reordering his ammunition stores for easy access.

Word of the impending fight spread across France. A new rail line from Paris had just opened; Cherbourg’s hotels filled with tourists eager to witness history. French Impressionist painter Edouard Manet, usually said to have watched the battle from a boat, likely did not arrive until afterward and rendered his famous depiction from spectator accounts. On Friday the English yacht Deerhound arrived from the Isle of Jersey to meet her owner, John Lancaster of the Lancashire Union Railway, who had brought his family from holiday in St. Malo to see the show.

Leaving Port

Saturday, June 18, was stormy and heavy seas precluded combat, but Sunday dawned clear. By 6:10 am Alabama’s boilers were lit; by 7:50 she had sufficient steam; and at 9:45 she set out for open water. Deerhound, with the Lancaster family now on board, accompanied her from the anchorage, as did several little harbor pilot boats crowded with paying passengers. The French ironclad Couronne, on hand to enforce the host’s neutrality, escorted the little fleet out past the breakwater’s western tip.

Kearsarge was about five miles out in the Channel. Winslow had finished the morning inspection and was about to conduct Sunday services when a lookout called, “She’s coming!” Winslow ordered the crew to general quarters and Kearsarge farther out to sea. He had strict instructions not to infringe on French territorial waters and for once was following orders to the letter.

To the 19,000 spectators, picnickers, and vacationing families watching from the high ground around Cherbourg, especially to the west around the famous Chapel of St. Germain on the point of Querqueville, it must have seemed as though the Federals were running for it. The betting was hot and heavy, with the odds favoring Alabama. Peddlers did a brisk business in campstools, telescopes, and cheap binoculars.

By the time Kearsarge was six or seven miles from shore, her boilers had warmed to high pressure. Her guns were loaded with shells on five-second fuses. The 11-inch Dahlgrens had been pivoted over to starboard. Gun ports were lowered. Cannoneers stood with lanyards in hand. Thornton ordered sand scattered across the deck, lest it become slippery with blood. The ship’s officers shook hands and went to their posts. Winslow had gone to his cabin and traded his uniform cap for an old, weather-beaten one. Taking up station at the foot of the mizzenmast, he ordered Kearsarge to come about and asked for full steam.

Observers could see black coal smoke gush from the Union ship’s stack as she turned bow-on to the enemy. Unlike Alabama’s clean-burning anthracite, Kearsarge ran on Newcastle bituminous. There could be no doubt now that Winslow intended to make a fight of it. At the three-mile limit, Couronne sheered off to stand guard, but the Deerhound and pilot boats followed in Alabama’s wake as she closed on her enemy.

Semmes Addresses His Crew

Calling his crew aft, Semmes had stepped up on a gun carriage, much as he had that first time in the Azores almost two years earlier. He told them: “Officers and seamen of the Alabama! You have, at length, another opportunity of meeting the enemy—the first that has been presented to you, since you sank the Hatteras! In the meantime, you have been all over the world, and it is not too much to say, that you have destroyed, and driven for protection under neutral flags, one half of the enemy’s commerce, which, at the beginning of the war, covered every sea. This is an achievement of which you may well be proud; and a grateful country will not be unmindful of it. The name of your ship has become a household word wherever civilization extends. Shall that name be tarnished by defeat? The thing is impossible! Remember that you are in the English Channel, the theatre of so much of the naval glory of our race, and that the eyes of all Europe are at this moment, upon you. The flag that floats over you is that of a young Republic, who bids defiance to her enemies, whenever, and wherever found. Show the world that you know how to uphold it! Go to your quarters.”

Trading Broadsides

The Confederate guns were loaded with solid shot for maximum reach. One of Alabama’s portside 32-pounders had been rolled over to starboard, and both her big Blakely pivot guns were also swung that way. The forward 7-inch rifle had the advantage of range over any other gun in the battle, including even Kearsarge’s Dahlgrens, and Semmes was determined to strike the first blow.

The ships were still a mile apart when, at about 11 am, he ordered Alabama over to port. As her bow swung away the cannoneers realized their captain, right out of the box, was going for the Holy Grail of a gunfight at sea. With Kearsarge coming straight at them, he intended to “cross the T,” bringing all guns to bear on the enemy’s bow and raking her, stem to stern.

“She opened her full broadside, the shot cutting some of our rigging and going over and alongside of us,” reported Winslow. “Immediately I ordered more speed; but in two minutes the Alabama had loaded and again fired another broadside, and following it with a third, without damaging us except in rigging.” The Confederates’ aim was surprisingly high, but so was their rate of fire. “I was apprehensive that another broadside—nearly raking as it was—would prove disastrous. Accordingly, I ordered the Kearsarge sheered, and opened on the Alabama.”

The Union sloop peeled away to port. The ships passed starboard to starboard, less than a thousand yards apart. Winslow ordered, “Fire at your pleasure!” It was about 12 minutes into the battle. Kearsarge unleashed her first broadside to immediate effect. A 32-pound shell went through Alabama’s forward pivot-gun port, ripped the leg off one of the 7-incher’s crew, ricocheted off its side, and wounded a man at another gun.

Having nearly had his bow crossed, Winslow intended to turn the tables and cross the enemy’s stern. He ordered the wheel over, and Kearsarge banked hard to starboard. But Semmes had the same idea. Alabama likewise turned to starboard. The two ships swung around after each other’s tails, on opposite sides of a circle, broadside to broadside. To turn away now was to invite being raked their whole length.

“The remainder of the fight,” Kell recalled, “occurred at a distance of not more than 500 yards.” The wind was blowing from the west, though that mattered naught to steamers, which fought with furled sails. The current, flowing at about three knots to the southwest, bore the circling duelists toward Querqueville Point. Kearsarge, with a four-bladed prop and clean bottom, had the advantage of speed over the Alabama’s two-bladed prop and fouled hull. Only by a masterful job of seamanship could Semmes keep Winslow from gaining on him around the circle and crossing his wake. “I had directed my men to fire low,” he wrote later, “telling them that it was better to fire too low than too high, as the ricochet in the former case—the water being smooth—would remedy the defect of their aim, whereas it was of no importance to cripple the masts and spars of a steamer.”

Thornton’s Damage Report

A Union shot cut away Alabama’s spanker gaff (top rearmost sail), from which flew the ship’s Stainless Banner, white with a Southern Cross in the canton. The Union gunners cheered to see it fall; the Confederates cheered to see another run up the mizzenmast. “When we got within good shell range,” Semmes reported, “we opened upon him with shell.” At about 11:20, the forward 7-inch Blakely put a round into Kearsarge amidships, but her chain armor bounced it up and out through the engine room skylight. The Union crew had no time to celebrate their close call before another 7-inch round struck aft, shuddering the entire ship. “Mr. Thornton!” called Winslow. “See what damage that one did!”

Thornton had barely left his post when the Confederates’ 8-incher landed a shell near Kearsarge’s aft pivot gun. When the smoke cleared, three Union crewmen lay sprawled on the deck, two with horribly broken legs (one later died) and one with an arm nearly torn off. Few of the Confederate shells, however, had such explosive effect. “I should have beaten [Winslow] in the first thirty minutes of the engagement,” declared Semmes later, “but for the defect of my ammunition, which had been two years on board, and become much deteriorated by cruising in a variety of climates.”

Thornton reported a Confederate shell had lodged in the ship’s sternpost, a dud. Had it gone off, it would surely have opened Kearsarge up to the sea. As it was, her rudder was nearly jammed, requiring four men to turn her wheel and preventing her from gaining Alabama’s stern and finishing the fight.

“Sound the Alarm For Fire Quarters”

So far the Confederates had suffered just one man killed and two wounded, a nicked mainmast, and the lost gaffsail, but they were hardly winning the battle. “Perceiving that our shells, though apparently exploding against the enemy’s sides, were doing him but little damage,” Semmes reported, “I returned to solid-shot firing, and from this time onward alternated with shot, and shell.”

The Confederates poured it on, firing at almost twice the rate of the Union gunners. A 100-pounder blew a hole through Kearsarge’s stack, letting black coal smoke pour low over the deck. Two 32-pound shells entered right through the Federals’ own 32-pounder ports, miraculously not striking a single crewman, even though a gun captain was knocked down by the sheer shock wave and one shell caromed completely across the deck to start a fire in the opposite side hammock netting. “Sound the alarm for fire quarters,” Winslow ordered. As men doused the flames, the gun crews remained steady, waiting patiently for the smoke to clear, taking their time, taking careful aim.

Watching through his scope, Semmes said, “Confound them; they’ve been fighting twenty minutes, and they’re cool as posts.”

“My position was near the eight-inch gun,” recalled Kell. “An eleven-inch shell from Kearsarge entered a port hole and killed eight of the sixteen men serving that gun.” When the smoke cleared he saw, “The men were cut all to pieces, and the deck was strewn with arms, legs, heads and shattered trunks. One of the mates nodded to me as if to say, ‘Shall I clear the deck?’ I bowed my head and he picked up the mangled remains of the bodies and threw them into the sea.” Kell ordered a 32-pounder crew to take over the Blakely, and the battle went on.

Winslow had ordered his light guns to clear the enemy’s decks and his Dahlgrens to shoot low to open Alabama’s bottom. “Mr. Thornton!” he called. “Aim a trifle more below her waterline.” A Union shell that should have taken Alabama right in the engine room instead exploded in her packed bunker. For a moment a thick cloud of black coal dust enveloped the deck, but as it blew away the crew could see Semmes’ improvised inner armor had worked. Alabama was taking on water, but she was still in the fight.

“Strike the colors, Mister Kell”

The two ships turned seven complete circles, firing continuously into each other. Kell called down to the engine room for more steam and was told the boilers would explode if fed any more coal. The 7-inch Blakely, a small gun firing a big shell, had overheated. A fragment had cut Semmes’ right hand. He is reputed to have offered a reward to anyone who knocked out Kearsarge’s aft pivot gun, but suddenly the Confederate gun crews, stripped to the waist, streaming sweat and black with powder grime, were doused with seawater as the entire ship jolted sideways. An 11-inch shell had punched into her below the waterline.

It came at the worst moment. Five minutes sooner or later, and Alabama would have been pointed for France. She didn’t have to reach port, but merely the three-mile limit, for safety. Instead, she had already begun another turn, faced seaward, and now had to come all the way back around. Kearsarge, across the circle, was already headed toward shore, perfectly positioned to cut off her escape. “For some few minutes I had hopes of being able to reach the French coast,” reported Semmes, “for which purpose I gave the ship all steam, and set such of the fore-and-aft sails as were available.”

Waterlogged, a shot having smashed her steering gear, Alabama answered the helm sluggishly, coming around to port. A forecastle hand leaped to unfurl a jib sail at the bow and quicken her turn but was, upon exposing himself, disemboweled by a shell fragment. He held in his guts with one hand long enough to release the sail with the other before falling to the deck dead.

Alabama finally came around only to find Kearsarge off her port bow, between her and safety. Semmes’ pivot guns were now facing the wrong way; to port he had only the remaining pair of 32-pounders. Winslow, having kept him to starboard the entire time, had a full broadside ready to rake him from just 400 yards. He ordered Thornton, “Stand by with the grape.” At this moment a Confederate engineer came up from below to report the rising water had reached Alabama’s furnaces. The ship had lost power.

Semmes ordered Kell below to assess the damage. The lieutenant remembered, “The holes in the side of the poor old Alabama were large enough to admit a wheelbarrow.” He rushed back on deck, reporting she had at most 10 minutes left on the surface. “Strike the colors, Mister Kell,” Semmes told him. “It will not do in the 19th century to sacrifice every man we have on board.”

Abandoning Ship

Even as Alabama’s flag came down, Kearsarge hit her with one last broadside. Afterward Winslow insisted the Confederates’ two port-side 32-pounders had opened up on him and, thinking their flag had not been lowered but shot away, he merely replied in kind. “It is charitable,” Semmes would write, “to suppose that a ship of war of a Christian nation could not have done this, intentionally.”

Semmes sent a boat across to request assistance. The Union lifeboats had all been shot to pieces; it would take several minutes to unlimber a sailing launch and second cutter—a suspicious delay to the Confederates’ minds. Meanwhile Deerhound, which throughout the battle had remained a mile or so to windward, moved in under Kearsarge’s stern to offer aid. “Yacht ahoy,” answered the Federals, “lend a hand to save the people.” The French pilot boats joined the rescue.

By now Alabama was rapidly settling by the stern. “There was no fear nor hurry-up on the part of the men,” Kell remembered later. “Everything was done quietly, as if the crew were preparing for an ordinary ship inspection.” The officers saw the wounded into the boats, flung their swords into the sea, and jumped after them.

Shortly before 1 pm, about five miles off the Cherbourg breakwater, Alabama suddenly reared up out of the water, her bottom showing green with algae and copper patina and her damaged mainmast snapping from the strain. Then, swiftly, she slid stern first below the surface of the Channel. Twenty-six of her crew died with her, several sucked under after her. “After swimming off a few yards, I turned to see her go down,” remembered Kell. “As the gallant vessel, the most beautiful I ever beheld, plunged down to her grave, I had it on my tongue to call to the men who were struggling in the water to give three cheers for her, but the dead that were floating around me and the deep sadness I felt at parting with the noble ship that had been my home so long deterred me.”

Old Friends and Great Adversaries

Kell, Semmes, and about 40 of the crew managed to reach Deerhound, where owner Lancaster and his crew took them aboard. Asked his preferred destination, Semmes requested that they be landed at Southampton, England. Some of Winslow’s officers informed him that Deerhound was making off, but he refused to believe that she carried surrendered prisoners of war, let alone their captain. After Kearsarge put in at Cherbourg, he accused the English yacht of serving as a Confederate tender in violation of neutrality, setting off yet another international incident. The United States demanded the return of her rightful prisoners. England, where the Confederates were treated as heroes, refused.

Winslow, his reputation and career revived by the victory (the dud shell, still embedded in Kearsarge’s sternpost, was presented to President Lincoln, and now resides at the Washington Navy Yard), was promoted to rear admiral. He commanded the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Squadron until 1872. Within a year of retiring, he died of a stroke and was buried under a slab of granite from Mt. Kearsarge, New Hampshire, for which his ship had been named. She served, on and off, as a Navy showpiece until she struck a reef in February 1894. She was the only ship named for the mountain; four others have been named after her.

Semmes ran the blockade to return to the Confederacy, also made rear admiral, and captained an ironclad in the James River Squadron. He ultimately had to destroy his ships to prevent their capture. He even served as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army—the only American officer to hold both ranks simultaneously—but was commanding nothing more than a muddy trench near Danville, Virginia, when word arrived of the surrender at Appomattox. He died in 1877 of food poisoning.

There is no record the two ever met again. Semmes, at least, preferred to remember Winslow as an old friend rather than his greatest adversary. “I had known, and sailed with him, in the old service, and knew him then to be a humane and Christian gentleman,” he wrote. “What the war may have made of him, it is impossible to say. It has turned a great deal of the milk of human kindness to gall and wormwood.”

The Alabama Discovered

In 1984 the French sweeper Circé, clearing 40-year-old mines, located a sunken shipwreck in the vicinity of the battle. Robot subs and divers revealed it to be Alabama, lying 180 feet down and about 30 degrees to starboard, partly sheltered by undersea sand dunes. The United States, France, and England all laid claim, but what had been international waters in 1864 were, 120 years later, within France’s 12-mile limit. Strong tides prevent the wreck from being raised, but today Alabama artifacts can be found on both sides of the Atlantic, including the ship’s bell, the 7-inch Blakely (found with a shell still in the barrel), several of her 32-pounders, and a brass ring from her wheel inscribed with her motto, “Aide toi et dieu t’aidera.” God helps those who help themselves.

I saw Manet’s painting hanging on a wall in Muse d’Orsay in Paris in May 2011. This was an unknown new story to me. The next day while visiting an American library in Paris I asked the librarian if she knew any more about this naval sea battle of our civil war off the coast of France, and it was unknown to her as well. Six years later, in the summer of 2017, I had the chance to visit the US Naval Academy in Annapolis and saw their lovely naval history museum. I asked the host volunteers if they knew anything about the sea battle between the CSS Alabama and the USS Kearsarge but it was unknown to them as well. Thank you to whoever put this article together as it has satisfied a long time of mine to hear more of the story of which Mr. Manet tried to capture in his painting.

“Battles and Leaders of the Civil War” has, as it did typically, an account of the fight from both sides, Union and Confederate viewpoints. The 4 volume set that I have has it in the fourth volume. If you have a chance to get this landmark account of the conflict from the participants themselves it’s very well worth it. I referred to them many times while reading other books later on.

Thank you for this account of the sea battle…I do wonder what would have been the result if the ALABAMA had chosen to be repaired/refitted, rather than filled with anthracite coal…?

I imagine the CSS Alabama would have been trapped in port and lost to the Confederacy for the balance of the war.

What a great story! Well and truly written. Thanks!

Side note: The British had abolished slavery in their territories a half century previous but many held a rather schizophrenic attitude toward the Confederacy and slavery for several reasons. Commercially, they wanted southern cotton as the Egyptian product alone was not enough to supply the country. Emotionally also, the British felt closer ties to the South from colonial days. Finally, the make up of many Northern areas of Catholic immigrants, Irish in particular, and continental religious and political dissenters engendered correct, but not especially warm, relations between elements of both countries. After the Civil War, an ambitious Napoleon III in France and a rising Prussia on the continent influenced Britain to a more cordial relationship with America.