By Kevin O’Beirne

In the fourth summer of the Civil War, things were not going well for the Union. After more than three years of bloody conflict the Confederacy, although on the defensive and having lost significant territory, was still defiant and dangerous, while the war-weary North wondered if victory was truly attainable. In the spring of 1864, President Abraham Lincoln had appointed Gen. Ulysses Grant as general-in-chief of all Federal armies and, for the first time in the war, the ponderous blue forces were employed in some concert with each other.

There were high hopes in the North when the spring campaign of 1864 had started off in early May. Gen. William T. Sherman led an army of more than 100,000 men out of Chattanooga toward Atlanta; George Meade led the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac overland toward the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia; Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James made an amphibious landing between Richmond and the vital rail center of Petersburg, Virginia, and Franz Sigel led a small army up (that is, in a southwesterly direction) Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

But within weeks, many of Grant’s plans lay stalled or in ruins in bloody earthworks in Georgia and Virginia. Meade’s Army of the Potomac, with which Grant traveled, had fought an astoundingly bloody series of non-stop engagements between the Rapidan and James rivers. Grant and Meade pushed toward Richmond while their opponent, Gen. Robert E. Lee and his gray-clad Army of Northern Virginia, exacted an ever-higher toll from the Federals.

The Shenandoah Valley is a 160-mile long avenue in Virginia, varying in width from four to 25 miles, between the Blue Ridge on the east and the Allegheny Mountains on the west. It runs more or less northeast along the course of the Shenandoah River from Lexington in the south to its confluence with the Potomac River at Harper’s Ferry. It was the breadbasket of Virginia and furnished many of the foodstuffs that sustained Lee’s army and the populace of Richmond. In addition to its value to the Confederacy as an agricultural center, the valley also served as a convenient route to invade the north; Rebel armies had repeatedly crossed the Potomac behind the protective barrier of the Blue Ridge.

Union armies had repeatedly been bested by their Confederate counterparts in engagements in the valley, as was again the case in early 1864. Barely a week and a half into the spring campaign, Sigel’s small army was put to flight at New Market by a numerically inferior force under Confederate Maj. Gen., and former United States Vice President, John C. Breckinridge.

Sigel was immediately replaced by David Hunter, a general with a troubling streak of independence. Hunter swiftly reorganized Sigel’s beaten army, issued orders for a Federal force in nearby West Virginia to join him and, two weeks after the defeat at New Market, set out up the valley. This time few Confederates were available to stop the Union force which, on Hunter’s orders, engaged in a campaign of random destruction of civilian property, culminating in the burning of the Virginia Military Institute in mid-June. Hunter soon had the entire valley under his control, and marched further south toward the important Confederate rail center and supply depot of Lynchburg, Va.

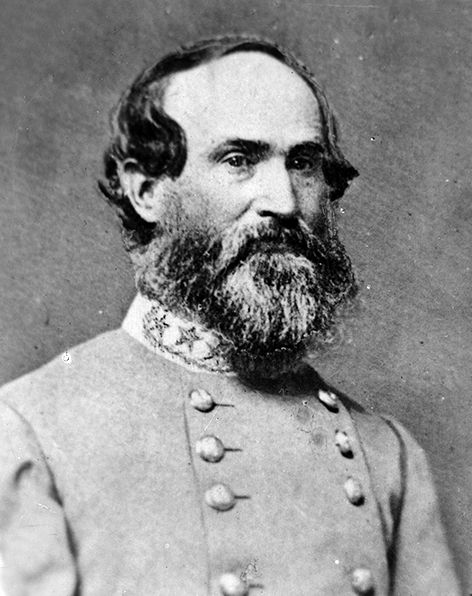

In early June, Robert E. Lee ordered his II Corps, under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, from Cold Harbor to Lynchburg. Early was charged with driving back Hunter and, if possible, making a demonstration north of the Potomac River toward Washington, DC. The caustic but competent Early did all this and more, and his appearance in the Shenandoah Valley touched off a vicious, four-month-long series of battles that would decide the fate of “the breadbasket of Virginia.”

Arriving at Lynchburg in mid-June, Early’s army of 12,000 men put Hunter’s force of 18,000 to flight, driving the Yankees without a major battle all the way into the mountains of West Virginia. With Hunter’s force out of the way, Early marched north down the valley, crossed the Potomac into Maryland and, less than a month after leaving the Rebel earthworks at Cold Harbor, was threatening Washington, DC. For a time Early posed a real threat to the seat of the Federal government.

To counter Early, Grant hurried the VI Corps of the Army of the Potomac north from Petersburg to Washington where it joined up with elements of the XIX Corps, a Federal unit recently arrived in Virginia after several campaigns in Louisiana. After a small battle only a few miles from the White House, the veteran Federals pushed Early back from the capital on July 12-13, 1864. The VI Corps chased Early across northern Virginia, while Hunter’s army, now under the direct field command of George Crook, came out of the mountains of West Virginia in an effort to squeeze the Rebels in a vise. “Old Jube” slipped the trap and escaped into the Shenandoah Valley.

The VI Corps started back toward Washington while Crook followed Early south up the valley. On July 24, however, Early’s 12,000 Confederates turned on Crook and roughly handled his force of 9,500 men at the second battle of Kernstown, two miles southwest of Winchester. Crook’s army retreated. The final straw occurred on July 30 when Early sent a Confederate cavalry brigade to burn the entire city of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in retaliation for Hunter’s depredations in the valley in early June.

The war was taking on an ugly new look and, with Federal forces stalled on battlefields from Virginia to Georgia and beyond, a Rebel army moving seemingly at will near the Federal capital was unacceptable to Lincoln, especially since 1864 was a presidential election year. Thus, the fate of the nation rested partly on developments in the Shenandoah.

Grant finally settled on Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, who took command of Union forces in the Shenandoah on August 7. Grant had offered Hunter the chance to remain in command on paper while Sheridan was in the field, but he declined and was relieved of his post.

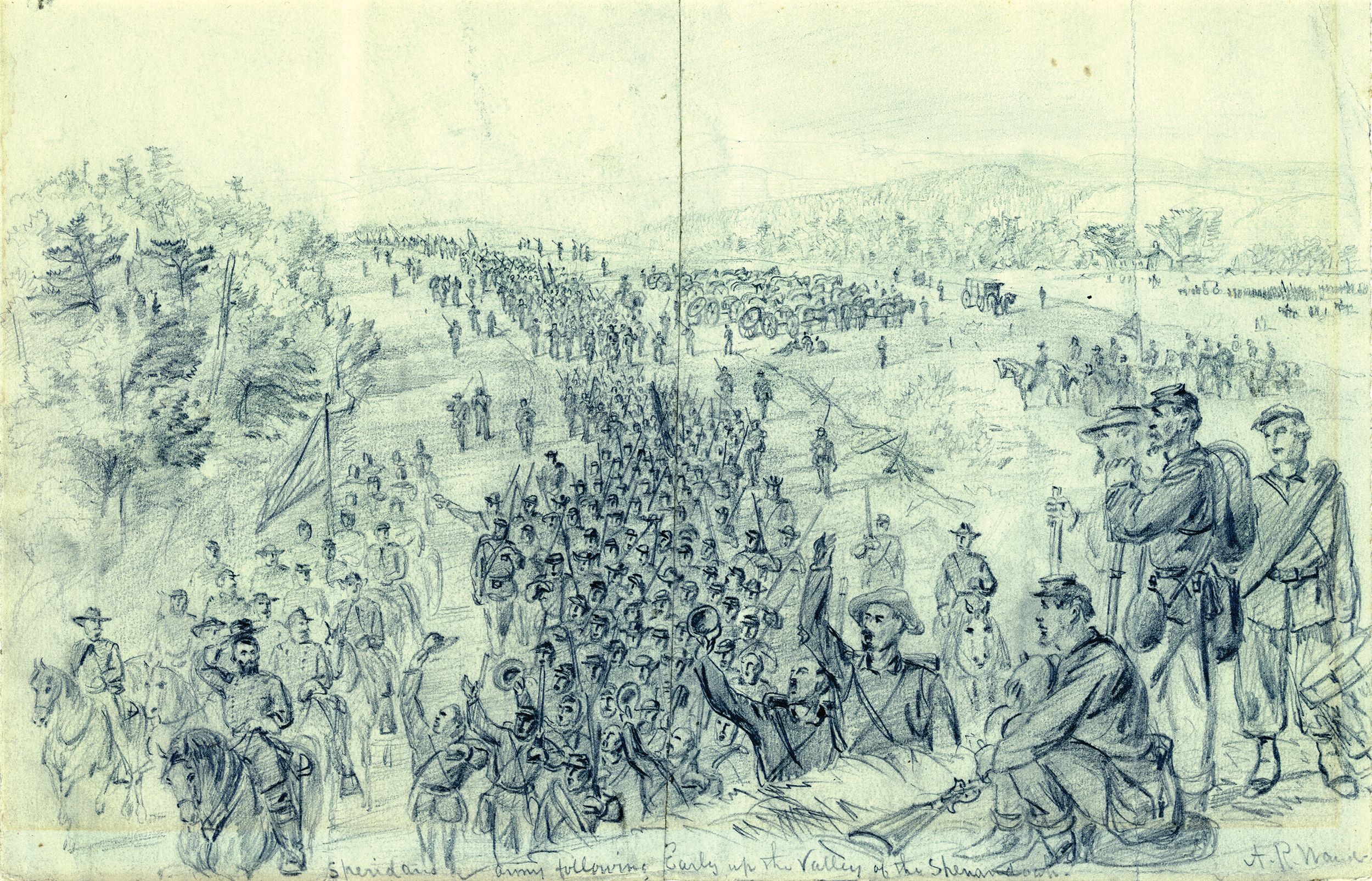

Sheridan’s appointment was at first ridiculed for reasons ranging from his youth and inexperience to his ungainly appearance, but Sheridan, the son of Irish immigrants, proved to be just the man for the job. Grant’s orders were for Sheridan “to put himself south of the enemy and follow [Early] to the death.” With a somewhat biblical tone, Grant added, “Wherever the enemy goes let our troops go also.” Sheridan received for his field command, which he dubbed “the Army of the Shenandoah,” several disparate units, and it would take all of his charisma to weld them into an effective fighting force.

From the Army of the Potomac came the VI Corps, 12,000 veterans under the command of Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, together with two cavalry divisions. He secured from Louisiana two divisions of the XIX Corps under the command of Brevet Maj. Gen. William Emory. He also received Hunter’s old command, designated as both the “Army of West Virginia” and as the VIII Corps, which included two infantry divisions and a cavalry division. Sheridan organized the cavalry units into a new corps under the command of Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert. In total, the Army of the Shenandoah mustered for action about 32,000 infantry and artillerymen and 8,000 cavalry.

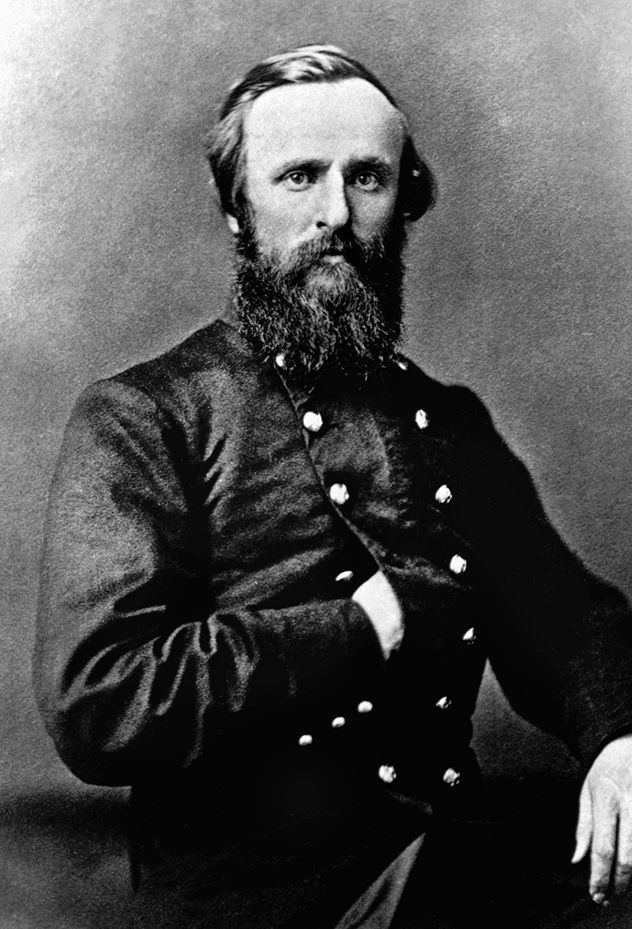

With Hunter’s departure, the small VIII Corps was commanded by Brevet Maj. Gen. George Crook. The corps, affectionately dubbed “The Mountain Buzzards” by Crook, was divided into two small infantry divisions, each numbering less than 3,500 men. The men held Crook in such high esteem that they usually referred to themselves as simply “Crook’s Corps.” These mountain troops, especially the 2nd Division, were hardened veterans but rustic in appearance. Crook was a competent 35-year-old Ohioan who had roomed with Sheridan at West Point, and was one of his commander’s most trusted friends and advisers.

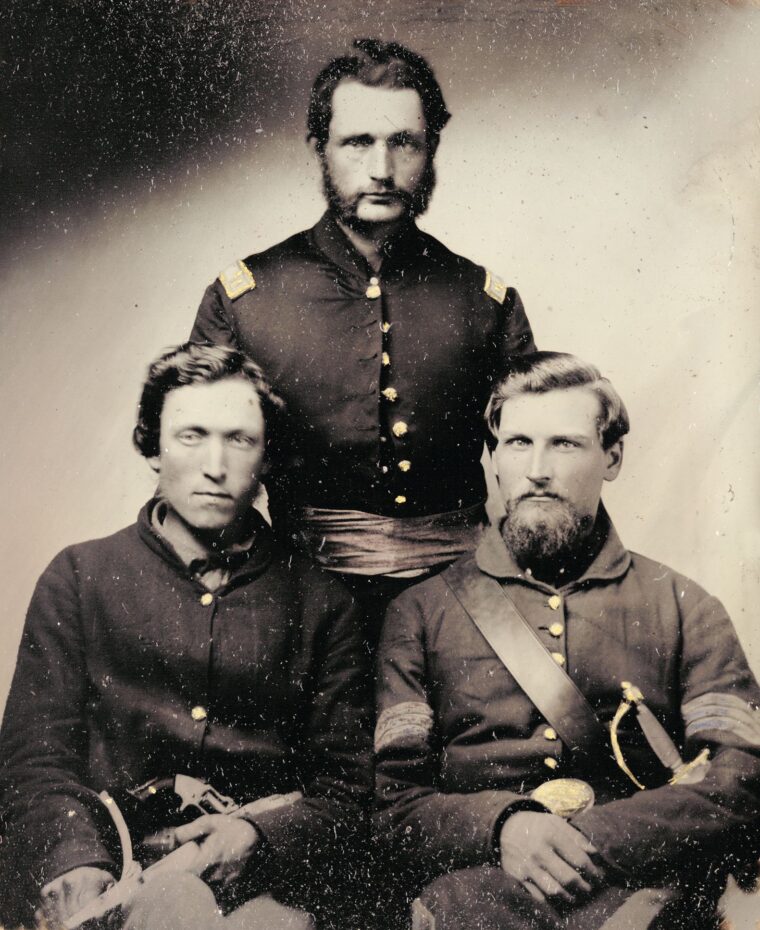

One of the toughest regiments in the 2nd Division of Crook’s Corps was the 23rd Ohio Veteran Volunteers. Organized at Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio, in the spring of 1861, the 23rd had seen hard fighting in three years of service and accredited itself well at Clark’s Hollow, South Mountain, Antietam, and dozens of minor actions in West Virginia’s rugged Kanawha Valley. The regiment featured a dazzling array of notables that was practically a who’s-who of important Ohioans, including two future U.S. presidents (Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley), future Congressmen, a future governor, future foreign ambassadors and, before the regiment was mustered out in 1865, five generals.

One of those future generals was Hayes, 41, a Cincinnati lawyer and aspiring politician who was the 23rd’s colonel in the summer of 1864. An original member of the regiment, Hayes had enlisted as major of the 23rd Ohio in June 1861, and, in January 1863, had succeeded to command of the regiment’s brigade (the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, VIII Corps) as a brevet brigadier general. He had no prior military experience, but in four years of war Hayes had gained a reputation as a competent officer with a good deal of personal gallantry. He was accomplished at leading large bodies of men, but retained a strong affinity for his own regiment.

On August 6, the 23rd began a march to Halltown, four miles west of Harper’s Ferry, where Sheridan was concentrating the Army of the Shenandoah. At dawn on August 10, the Army of the Shenandoah moved from its camps at Halltown marching for Berryville, 14 miles due south. Early’s 12,000-man Army of the Valley was drawn up near Bunker Hill, West Virginia, 12 miles west of the Federals and 12 miles north of Winchester. At Berryville, the Federals would threaten Early’s lines of supply and communications, which ran through nearby Winchester.

As expected, Early pulled back from Bunker Hill and headed south up the valley. Led by the VIII Corps with the 23rd Ohio, Sheridan followed to the banks of Cedar Creek, 15 miles south of Winchester. After a few days of skirmishing along Cedar Creek, in which the 23rd Ohio lost six men, Sheridan was informed, incorrectly, that Early had been heavily reinforced. Believing himself outnumbered, Sheridan commenced a withdrawal northward through rain and stopped only when he reached his old lines at Halltown.

Early’s gray-clad soldiers followed. After stabbing at Sheridan’s rear guard at Charlestown in a brisk action on August 21, the Rebels encamped just outside the Federals’ Halltown lines. “Old Jubilee” made the grave mistake of interpreting the withdrawal of Sheridan’s numerically superior army as a sign of possible timidity on the part of its commander—a notion that would cost him dearly before it was dispelled.

At about 6 p.m. on August 22, the 23rd Ohio and two other regiments from Hayes’ brigade, accompanied by the commander of the 2nd Division, Col. Isaac Duval, were sent on a reconnaissance to locate the right end of Early’s newly arrived line. Hayes reported that his three regiments charged the Confederate picket line “with great vigor” and “drove them perhaps half a mile.” Satisfied of the location of the Rebel line, Duval ordered Hayes to withdraw. The 23rd suffered two casualties; the Confederates lost 20 killed or wounded, and 20 captured. Hayes wrote to his wife of the successful reconnaissance, “It is called a brilliant skirmish and we enjoyed it very much.”

At Halltown, the opposing lines were very close and often “quarrelsome.” Staff officer Hastings recalled visiting the picket line one day and finding all the sentinels “well under cover,” except for one lad who “could not restrain himself from occasionally getting [up] and crowing like a rooster. He did it one too many times and finally received a shot in the leg.”

After the incident, Hastings noticed a white flag flying from the Rebel line and he heard a Southern voice calling, “Hello Yank.” Hastings replied, “Yes Johnny, what do you want?” Between the opposing lines was “a promising cornfield full of luscious corn just fit for eating.” The apparently hungry Confederate replied, “Let’s stop firing for dinner and get some roasting ears.” After some parlaying, a truce was agreed to and, as Hastings recalled, “into the field went both lines mingling quite freely.” When dinner was over, a Yankee called, “Hello Johnny Reb. All through with dinner?” The Confederates called back, “Say when you are ready.” The men of both sides quickly took cover. Hastings wrote, “At the word, ‘Ready’ bang went the rifles all along the line.”

On August 25-26, Early withdrew most of his army from the Halltown lines and started toward the Potomac, hoping to scare Sheridan with the threat of a repetition of his Washington raid in July. Except for dispatching cavalry to contest the Confederate thrust, the Union commander did not take the bait. The following day, Sheridan ordered Crook to see what Confederates, if any, were to the Federals’ front.

On August 27, Hayes wrote, “We had quite a little battle last night … my brigade, in connection with the Second Brigade, again attacked the rebel picket-line with decided success.” The Federal battle line charged across the same cornfield where Union and Confederate soldiers had bartered and picked ears for dinner only a few days before. The charge across the mature cornfield was harrowing, “as the bullets seem magnified in number as they cut from leaf to leaf.”

Hayes’ brigade overran a South Carolina regiment and captured it, field officers and all. The Yankees pushed on, butted up against another line, traded a few shots, and retired. During the retreat, Rebel artillery opened on the Federals and Hastings claimed he actually saw a shell coming at him; he ducked and “felt the [shell’s] rush of air and it burst with a bang a few feet [to the] rear … I am thankful Hayes didn’t see me do it [dodge].”

Hayes wrote, “My loss was 3 killed and 21 wounded. This attack was similar in character to the former [August 22 reconnaissance], but was made in greater force and with results proportionably [sic] greater. The loss of the enemy was 104 officers and men captured and about 150 killed and wounded.” His opinion of the 23rd Ohio was sky-high: “My old regiment keeps up not withstanding the losses. We have filled up [recruited] so as to have in the field almost six hundred men—more than any other old regiment.”

On August 27 Early withdrew back to his old position at Bunker Hill, about 12 miles north of Winchester. Sheridan moved from Halltown five miles to Charlestown on August 28. The army stopped for the night just south of Charlestown and threw up earthworks.

One of the sharper skirmishes in the northern Shenandoah Valley occurred on September 3. That day, Crook’s VIII Corps, with the 23rd Ohio, marched south 10 miles toward Berryville, hoping to cut off the Winchester-Berryville Pike, which ran east from the Rebel supply center at Winchester to Front Royal in the Blue Ridge. At the same time, Kershaw’s Confederate division, having been recalled to Petersburg by Robert E. Lee, was marching toward Front Royal along the very road that Crook was hoping to block.

By 3 p.m. Crook’s Corps was near Berryville and astride the turnpike. After a hard march the men of the 23rd were ordered on picket soon after dropping their knapsacks. The regiment marched out to the picket line, sentinels were posted, and the outposts had just kindled fires to cook supper when firing was heard. Thinking that the musketry was from nervous recruits in another brigade, the veterans of the 23rd ignored the noise. The racket continued and, as reported by a member of the regiment, “an hour before sunset the enemy was reported to be advancing.”

An officer recalled, “The bugle sounded the alarm and every man sprung to the ranks. It was a laughable sight to see the line formed with nearly every man holding a tin cup of coffee in hand, chewing and munching crackers and bacon.”

Kershaw’s Division, under the overall command of Lt. Gen. Richard Anderson, marched up the turnpike right into Crook’s men. Thinking the Yankees were few in number, the Rebels charged and drove back a few regiments on the flank of the 1st Division of the VIII Corps. The 23rd Ohio’s division was brought up in support with Hayes’ brigade in the lead. Taking up a position behind a stone wall, Hayes’ Ohioans and West Virginians were immediately overrun by stampeding Federals from another brigade fleeing through their ranks. Hayes’ soldiers jeered the routed men as Hastings recalled, “Our attention was quickly diverted from this fleeing mob by the onrush of the Confederate line.”

Following the routed Yankees, “The Rebels were sure of victory and ran at us with the wildest yells, but our men turned the tide in an instant,” remembered an officer in the 23rd.

Years later Hayes recalled, “We stood behind a terrace wall, the ground [on the Rebel side] being level with the top of the wall.”

Hastings wrote, “On they came like devils. When the Confederate line was not more than one hundred feet away, our boys gave them a murderous volley.” Calling for a charge, Hayes jumped his horse over the terrace wall, closely followed by his cheering brigade. Hastings remembered that the Rebels “turned and ran.”

After retreating a few hundred yards, the Confederates rallied and took up a position behind a stone wall and checked the Federal charge. The two sides slugged it out in the gathering darkness, standing their ground and pouring volleys into each other.

Lt. Col. James Comly, the 23rd’s commander, wrote that “it was a magnificent fight—the only one I ever was in where I felt sure of being killed.” Comly’s premonition very nearly came true. After dark, as the battle continued, he was speaking to his adjutant about the performance of the draftees in the 23rd’s ranks when a shell passed between his body and his horse’s neck. Hastings rode over to the 23rd and Comly informed him that the regiment was losing many men and said, “If it was not dark, I should ask the privilege of charging the enemy in my front and have it over one way or the other, this is hellish work and hard to bear.”

The firing continued unabated until 10 p.m. Hayes recalled, “We wished we were out of this—we would quit if their side would quit. Crook sent us word, let the fire die down if you can, but don’t leave as long as there is any firing; fire as low as they do. So we would give orders to our men to let the fire drop, and our men would fire more and more rarely, until a shot here and there; then suddenly two or three would fire at once, and the whole army on both sides would fire again, until it finally died out.”

The 23rd and the rest of Hayes’ brigade were on the line until midnight, when by unspoken agreement the bloodshed ceased. Hayes wrote that Berryville was “one of the fiercest fights I was ever in” and speculated, “I suppose I was never in so much danger before.” But he also said, “I enjoyed the excitement more than ever before,” and added, “Prisoners say it is the first time [Kershaw’s] division was ever flogged in a fair fight.”

Hayes reported that his command captured 75 Confederates and killed or wounded 200 more, while the 23rd Ohio lost 11 men in the action including Hayes’ personal color bearer, Pvt. George Brigden, who was shot through the kidneys. Overall Federal losses amounted to 166 men.

The following morning, Early arrived with the rest of his army intent on destroying Crook’s Corps, but when he saw the Federal position entrenched in a continuous line for several miles from Berryville northward, the Confederates fell back to the west side of Opequon Creek, just east of Winchester. The Army of the Shenandoah remained on the Berryville-Summit Point line for nearly two weeks. Expecting that Anderson’s troops (Kershaw’s Division and an artillery battalion) would be called back to Petersburg, Sheridan was attempting to secure positive information on their whereabouts; when Early’s army was reduced, he intended to attack and destroy it.

On September 8, the 23rd marched from Sheridan’s left to the Federal right, at Summit Point, where things were fairly quiet. Hastings estimated that, since Sheridan had assumed command, the 23rd Ohio had marched 151 miles, engaged in four reconnaissances and one battle, and had been on the skirmish line for many days.

On September 16, the 23rd Ohio was ordered to Harper’s Ferry to serve as guards for a wagon train, as the Confederate partisan Mosby had lately been operating along Sheridan’s supply lines. Comly reported, “Waited with the regiment at Charlestown while [the] train loaded at Harper’s Ferry. General Grant here today to visit with Sheridan. Passed through our camp. [Grant] had only one orderly—nobody else—with him. Not much like McClellan, that!” The 23rd’s return march from Charlestown commenced at 2 a.m. on the 18th and the regiment arrived back in their camp near Summit Point later the same day.

On September 17, the bored Hastings wrote, “We conclude that this is a quiet before the storm and to wait in patience.”

Hastings was absolutely correct. They were on the verge of the largest, hardest fought, and bloodiest Shenandoah Valley battle of the entire war. Even as the men of the 23rd Ohio escorted their wagon train from Charlestown to Summit Point, events were being set in motion that would result in a collision of the two armies just west of Opequon Creek.

Opequon Creek was a watercourse that arose southeast of Winchester and flowed north, on the east side of the town, and eventually discharged to the Potomac River. The terrain around Opequon Creek was fairly flat and consisted of open fields interspersed with small stands of woods.

For two weeks Sheridan had bided his time, waiting for Lee to recall Kershaw’s Division to Petersburg. Lacking firm intelligence on the composition of Early’s force, Sheridan had to rely on the word of a Union-sympathizing widow in Winchester. This informer smuggled a message to the Yankee commander wrapped in a tinfoil wad carried in the mouth of a slave who sold vegetables in Winchester each day. Through this source, on September 16, Sheridan received word that, two days before, Kershaw’s Division and its artillery battalion had departed from the valley. This was the news Sheridan was waiting for and he immediately set about planning the destruction of Early’s army.

The following day, Sunday, September 18, Sheridan learned that Early had divided his force the previous afternoon in the face of his “timid” Union opponent and marched with two infantry divisions to destroy Baltimore & Ohio tracks in Martinsburg, 20 miles north of Winchester. The Confederates reached Martinsburg early that Sunday morning. There, in a captured telegraph station, Early read a dispatch that mentioned Grant’s meeting with Sheridan the day before. The General-in-Chief’s presence in the Valley could mean only one thing—action by the Army of the Shenandoah, and soon. A shaken Early immediately ordered his two divisions back to Winchester. The gray soldiers marched rapidly southward, hoping to avoid the piecemeal destruction of their army.

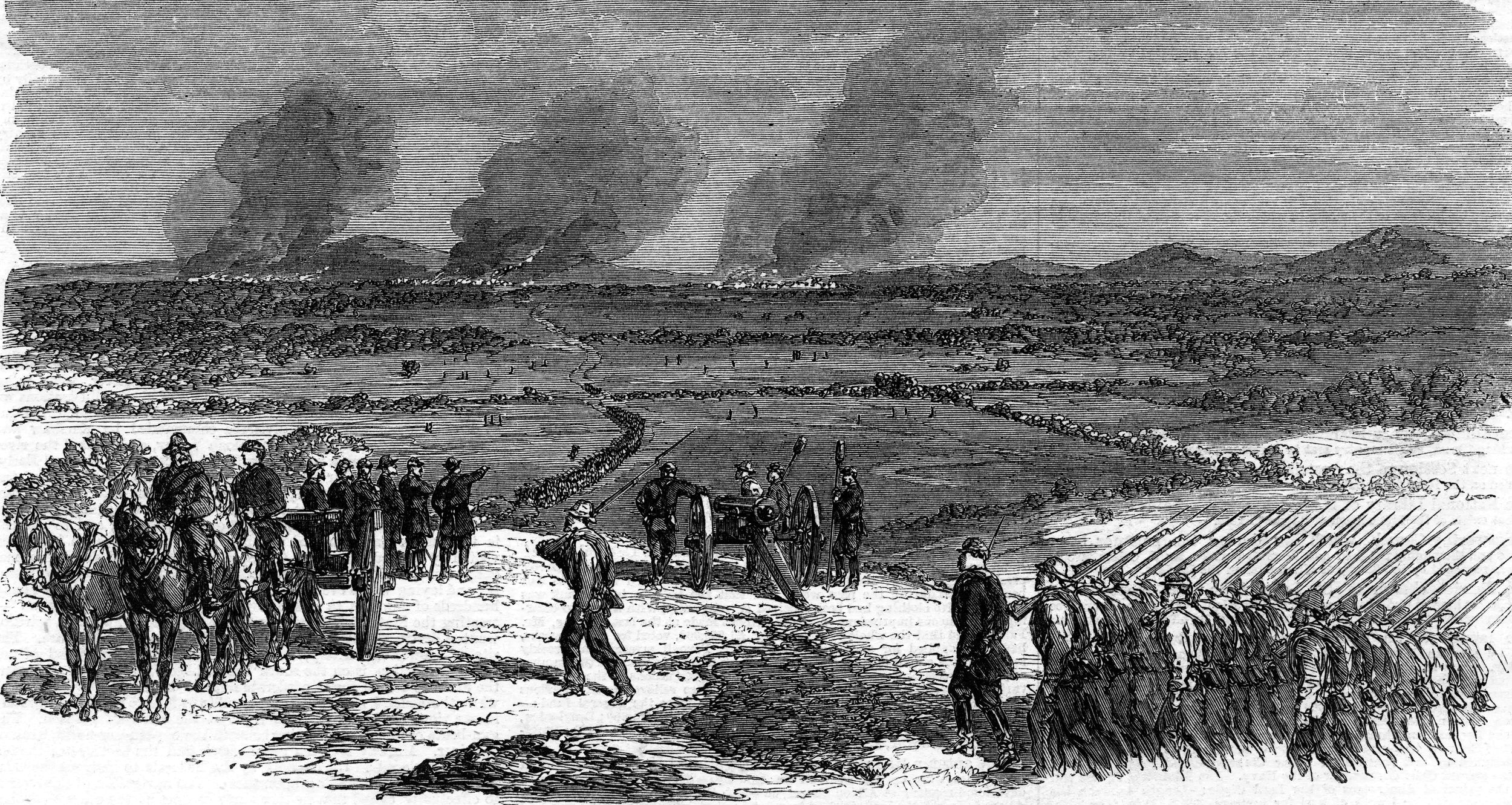

Sheridan’s original plan called for a march around the southwest side of Winchester to sever Early’s supply and communications line by gaining the important Valley Turnpike, where he would take up position and wait for attack by the numerically inferior Confederates. However, when news reached him that Early was apparently trying to hand him a victory by dividing his forces, Sheridan changed tack. He now intended to demonstrate in front of the Confederate units in position due east of Winchester with the VI and XIX Corps, while Crook’s “Mountain Buzzards” flanked the Rebel line from the south, and Torbert’s cavalry corps hit them from the north.

Orders for the march reached Hayes’ headquarters at 8 p.m. on Sunday. The men of the 23rd Ohio were informed of the order to march before dawn, but were not told their destination. One wrote, “As the men stood in ranks for an hour the subject of direction [of the march] was discussed somewhat, not much though, as we were veterans who took little interest in what the orders were to be, only executing the order when it came.”

The Army of the Shenandoah was roused from its camps about Berryville and Summit Point before 1 a.m. the following morning (September 19). An hour later the column was on the road, with Crook’s Corps bringing up the rear. At 4:30 a.m., the Federal cavalry division of James Wilson, riding west on the Winchester-Berryville Pike, splashed across Opequon Creek, about six miles east of Winchester. The horse soldiers thundered through Berryville Canyon, a narrow, two-mile defile through which ran the Pike, and scattered Confederate pickets of a North Carolina regiment from Ramseur’s Division. Emerging from the defile, Wilson’s troopers drove off a brigade of infantry and took up position on a hill to cover the advancing infantry.

It was at this point that Sheridan’s plans began to unravel. His strategy called for a swift strike on the Rebels just beyond the defile but, to accomplish this, he intended to funnel over 23,000 troops of the VI and XIX Corps down the single roadway through the narrow canyon. The result was a gigantic traffic snarl that made Sheridan’s Irish temper rise to fever pitch. The VI and XIX Corps were not out of Berryville Canyon and ready for deployment until after 10 a.m. By this time, Early’s hard-marching “foot cavalry” had enabled the Virginian to concentrate his army. Sheridan’s chance to destroy Early piecemeal was gone. From south to north, Early positioned the divisions of Ramseur, Rodes, and Gordon; around Stephenson’s Depot to the north, under the overall command of the capable John Breckinridge, was Wharton’s Division of infantry and the small cavalry divisions of Lomax and Fitzhugh Lee.

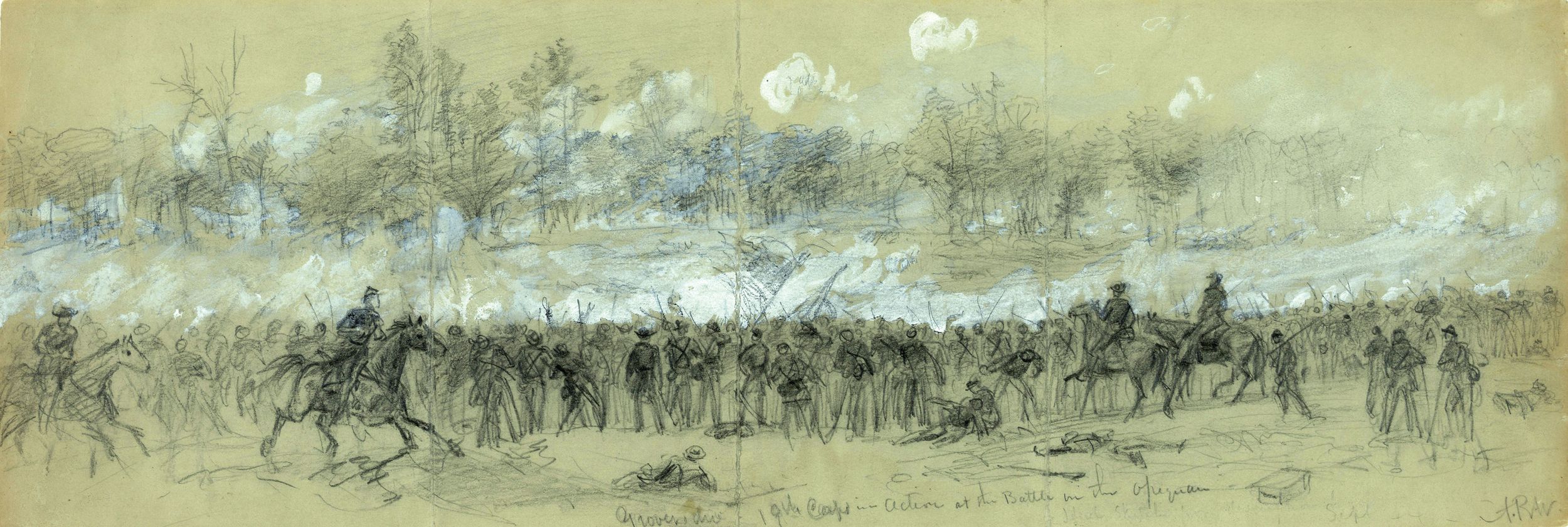

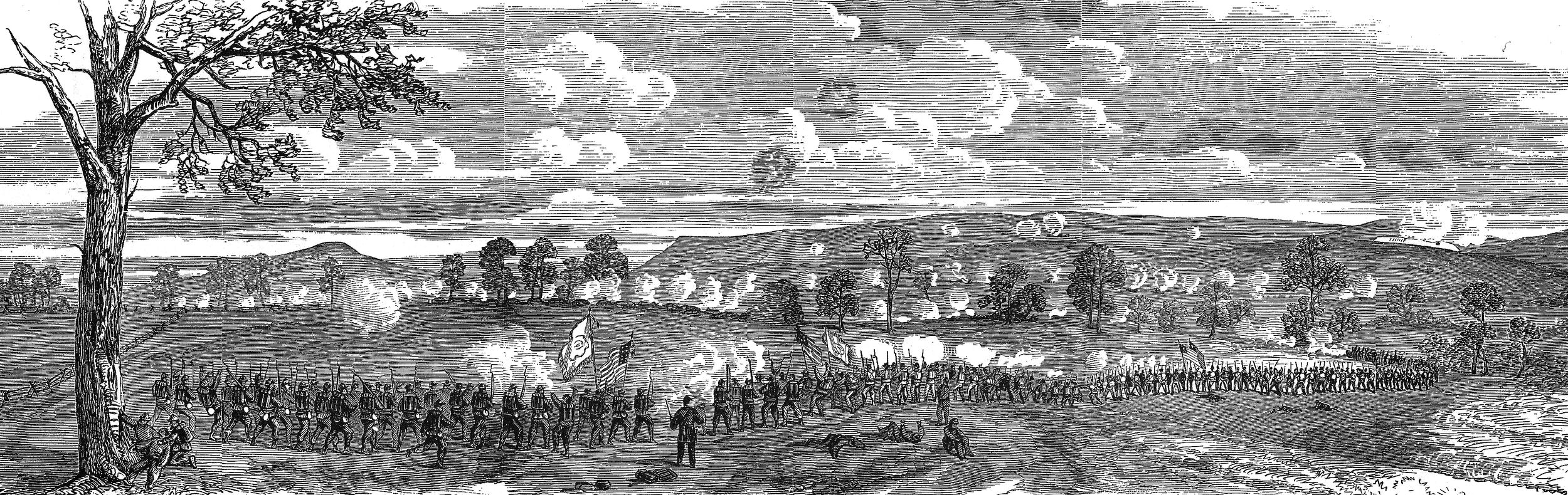

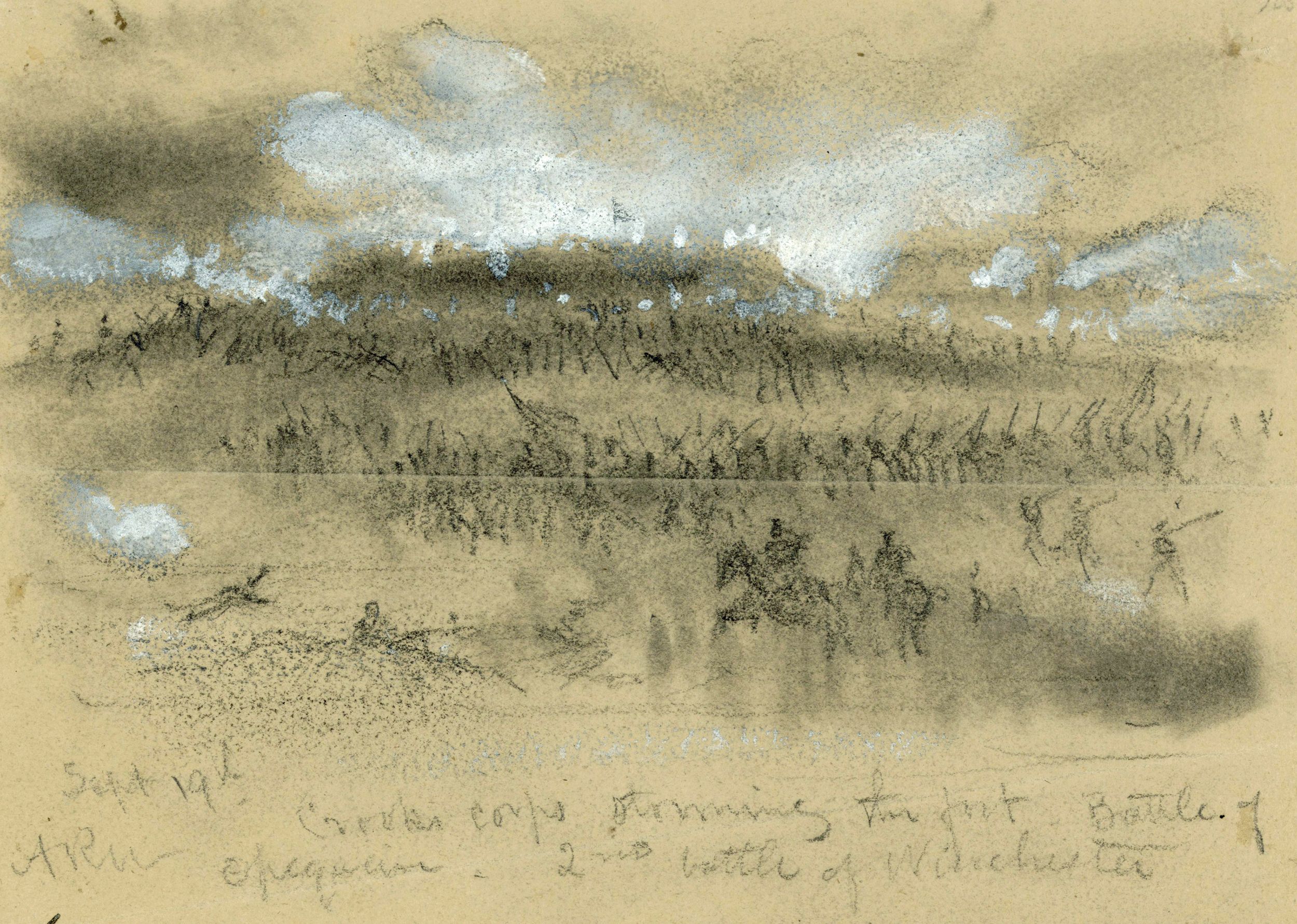

At 11:40 a.m., an impatient Sheridan launched a massive assault with four divisions comprising almost 20,000 men. The VI Corps went in on the south end of the line, astride the Winchester-Berryville Pike, while Emory’s XIX Corps advanced through woods and fields north of the VI Corps and just south of an east-west running creek called Redbud Run. Crook’s men were held in reserve almost three miles away at the other end of Berryville Canyon.

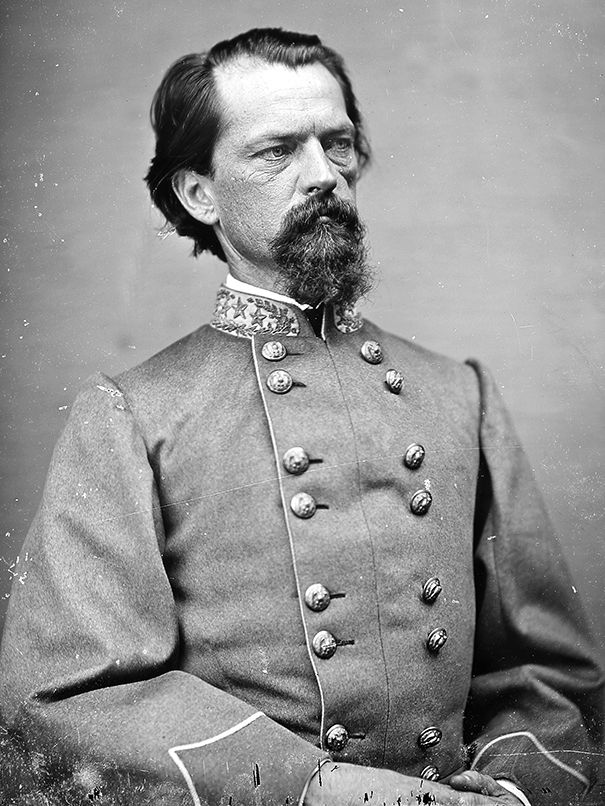

The assault was a Federal disaster, as Early’s veterans once again demonstrated their fighting prowess. In particular, Emory’s men were badly mauled, losing more than 2,000 men in the attack. The VI Corps suffered fewer casualties but, like the XIX, achieved nothing. When a gap opened between the VI and XIX Corps, the veteran Confederate division of Robert Rodes drove right through it, creating panic in the Federal ranks. Grimly surveying a fleeing throng of thousands, Sheridan ordered Crook to bring up the VIII Corps. Meanwhile, the Federals’ only reserve division on the scene, David Russell’s (VI Corps), advanced and broke the momentum of Rodes’ attack. Both Rodes and Russell were killed in the fighting, after which a temporary quiet settled over the lines. “Old Jube” exulted that he had defeated Sheridan, and Confederate morale soared, but Sheridan was not through yet. He had plans for Crook’s men.

In the predawn hours, the 350 or so men of the 23rd Ohio, marching near the head of the VIII Corps’ column, had tramped south cross-country eight miles to the bridge where the Winchester-Berryville Pike crossed Opequon Creek. The Buckeye soldiers were in good spirits that morning “with the delight of being on the march once more,” one man maintained, and arrived at the head of Berryville Canyon between 10 and 11 a.m. The men stacked arms “in a beautiful clover field” and fell out to boil coffee and await orders. The sound of cannon firing three miles to the west was a reminder of the battle being waged, convincing the men that “there was serious work to be done before night.” For the time being, the men of the 23rd Ohio and the VIII Corps were content to let the VI and XIX Corps tangle with Early’s veterans.

Hayes and his staff lay in the clover field “on that bright sunny midday,” chatting, cracking jokes, and listening to the battle. Sheridan’s signal station was in plain view of Hayes’ reclining officers and, when Rodes’ Division crashed through the hole in the blue line, the men of the brigade noticed that the flags began to move “in a quick nervous way.” Hastings noted, “An impression began to prevail that the battle was not going as it ought … and that we should soon be ordered into the thick of it.”

Soon, a staff officer was seen galloping out of the canyon. An officer beside Hastings muttered, “I wonder if that damned fool isn’t coming over here to tell us to go in.” Without orders, the 1,450 men of Hayes’ brigade scrambled to their feet, adjusted their accouterments, and fell in near the stacks. The staff officer presented Sheridan’s compliments and informed the officers that the VIII Corps was ordered to the front and that he would act as a guide.

A cynical Hastings thought the officer’s delivery “a very polite way of ordering a fellow into the jaws of death.”

At noon, the men fell in and were soon marching in a column of fours up the pike toward the canyon. Ominously, as the 23rd Ohio tramped across the bridge over Opequon Creek, they passed a field where surgeons were already performing amputations on the morning’s casualties. The 23rd entered the defile, where they were greeted by a confusing mass of ambulances headed for the field hospital, parked wagons, stragglers, and walking wounded who implored the “Mountain Buzzards” to march fast, lest the Federal line give way. To make headway, the column split and marched along both sides of the road. One officer grimly noted, “It certainly was not a pleasant afternoon walk.” In his memoirs, Crook averred, “There seemed to be as many fugitives as there were men in my command.” It took Hayes’ brigade more than 90 minutes to make the two-mile trek through the congested canyon.

Sheridan wrestled with what to do with Crook’s men. His original plan called for them to march south, flank the Rebels, and cut off their line of retreat. Now, worried about the shaky XIX Corps, he ordered Crook north to support them, pending development of an opportunity. Sheridan told Crook to “look out for our right.” Exhibiting his usual aggressive style, he also ordered the Ohioan to send one division to locate the Confederates’ left (north) flank and to “there strike and carry it at all hazards.” Sheridan warned Crook that Torbert’s Federal cavalry was to the north and to be on the lookout for friendly units.

Emerging from the west end of the canyon, the 6,000 men of the VIII Corps turned north and marched through woods along the rear of the XIX Corps. After marching nearly six miles from the bridge at the Opequon, the column was finally halted in a stand of woods. Hastings remembered, “[Artillery] shells were exploding all around, limbs being cut from trees and falling on the troops below.” Crook posted his 1st Division, under Col. Joseph Thoburn, immediately behind the XIX Corps’ right (north) flank. Upon General Emory’s request, Thoburn soon relieved a division of the battered XIX Corps and took up a front-line position with his right flank resting on Redbud Run.

Meanwhile, in obedience to Sheridan’s orders, Crook accompanied his 2nd Division, commanded by Col. Isaac Duval, with Hayes’ brigade in the lead, even farther to the right. Marching down a farm lane, the small division crossed to the north bank of the swampy Redbud Run on a rickety bridge. The men knew they were on a flanking march and, as related by Hastings, looked for the chance to even the score for their humiliating defeat by Early at Kernstown on July 24. The march passed through “deep valleys, over wooded hills, across open fields, and through dense thickets; on we went for a mile or more.” The division moved as fast as possible through the rough country as “every man of the command knew a crisis had arrived … and felt in a manner that the results of the battle rested on him.” The column turned westward toward Winchester and continued for another half-mile. Duval’s men were now beyond the Confederate flank.

Crook sent one of his staff officers, Captain William McKinley of the 23rd Ohio, back across Redbud Run with orders for Thoburn to attack when he heard the sound of Duval’s guns. McKinley then rode on to report to Sheridan Crook’s intention to commence the assault, and asked for support along the whole Union line. The time was about 3:30 p.m.

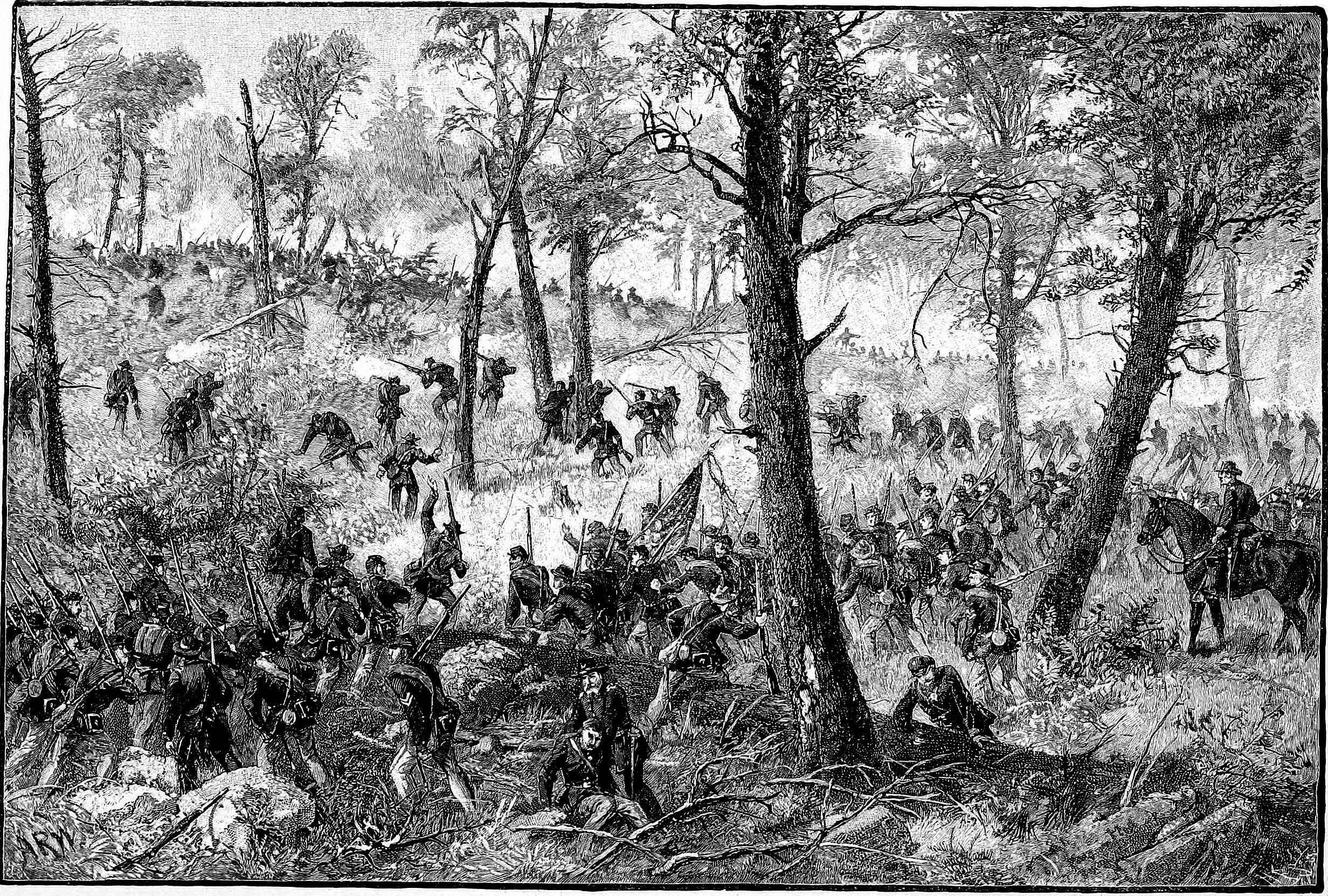

The column halted in an “almost impenetrable growth of cedar” where they fronted, facing toward the sound of the firing to the south. In the thick woods, Duval formed the division into two battle lines, with Hayes’ brigade in the lead. The 23rd Ohio was at the right-center of the front line. Skirmishers were advanced to the front and orders passed down the line that the brigade was to keep silent until it was within a hundred yards of the Confederates, “and then with a yell to charge at full speed.”

Upon Duval’s order, Hayes’ battle line stepped out of the thicket into an open field as the blue-coated skirmishers drove off some Confederate cavalry. One Rebel observed that Hayes’ brigade “advanced in a splendid line.”

The men of the 23rd Ohio scrambled over several fences, forcing Comly to dismount and lead them on foot. He remembered, “After advancing … over two or three open fields in this way, we reached the crest of a slight elevation.” Upon gaining the eminence, the men of the 23rd observed the panorama of the battlefield open before them. The main line of Gordon’s Rebel division was off to the left front, in front of Thoburn’s Division and the XIX Corps. Off to the right (west), Comly observed elements of Torbert’s cavalry advancing through open fields, moving parallel with Duval’s Division. As Hayes’ brigade gained the height, Confederate artillery over a mile away near Winchester opened a brisk fire on them. The flanking movement had been discovered.

“Now came hurrying times,” recalled Hastings. Hayes ordered his four regiments forward through an open field at the double-quick—a light jog. To Hastings, it seemed that “everything on the enemy’s left was turned on us, bullets, shot, shell, [and] shrapnel rained like hail.” The “Mountain Buzzards” rushed forward through the galling fire. The 23rd soon reached a thick line of underbrush; the bluecoats plunged into the thicket and stopped short. Hayes’ men had stumbled back upon Redbud Run. The men of the 23rd peered out from the growth at the center of a high-banked, reed-filled, 300-yard-long morass or slough, probably an old mill pond that had gone stagnant. Comly remembered the slough as being 20 or 30 yards wide, “nearly waist deep—with soft mud at the bottom and surface overgrown with a thick bed of moss.… It seemed impossible to get through it.”

Hayes remembered, “The Rebel fire now broke out furiously. Of course the line stopped. To stop was death. To go on was probably the same.” To retreat, however, was unthinkable. Quickly realizing that the men would cross the slough under fire only if led, Hayes “called out in a voice clearly heard above the hellish sound of the battle, ‘Come on boys!’” He spurred his horse down the steep bank and splashed into the sticky morass. As Comly shouted orders, the men of the 23rd Ohio poured down the bank after him, cheering. Holding their weapons and cartridge boxes out of the stagnant water, the regiment began to fight its way through the swamp. Upstream and downstream of the slough the other regiments of the brigade also began to cross.

Hayes’ horse plunged through the goo but midstream became “mired hopelessly.” He jumped off and, sometimes having to use all four limbs to move, was the first to reach the other side of the slough. Dripping and muddy, under shelter of the far bank he turned and saw hundreds of men struggling in the stream. Bullets found their marks as some soldiers slipped, wounded, under the waters of the swamp, never to rise again.

On the 23rd’s front, Comly was the second man across after Hayes. Years later, the Confederate commander on this portion of the field, Maj. Gen. John Gordon, recounted to Hastings, “When we first saw Hayes and his men coming over the hills, we rather laughed … knowing of this morass … but when on you came, plunging into the morass as though it was a mere pastime, we began to wonder of what metal [sic] such men were made.”

Comly and Hayes led the now-disorganized regiment up the steep bank where the men, “inspired by the right spirit … charged the Rebel works pell-mell in the most efficient manner,” driving off a line of graybacks from behind a nearby stone wall. Gordon recalled, “One of my staff officers remarked, ‘they must be devils’ and as [Hayes’s men] rose to the brink of the bank, away went my boys as though ten thousand devils were after them.”

The gray line reformed a few hundred yards from Redbud Run behind the stone walls around the Hackwood farmhouse. To the right of the 23rd Ohio, Hastings accompanied the 36th Ohio across the run and rode with its men as they impetuously assaulted the Rebel position at the Hackwood farm. He remembered, “[The 36th] suffered severely. All about the bridge, along the banks of the creek and up the lawn to the buildings the dead of the 36th were literally lying in heaps.”

Halting at the stone wall, the 23rd Ohio and the rest of the division were partially reformed and, “with a ringing cheer begotten of the enthusiasm of the moment,” charged on the new Confederate line. Several days later, Hayes wrote to his wife, “We steadily worked toward them under a destructive fire. Sometimes we would be brought to a standstill by the storm of grape and musketry.” He recalled how, when the Yankee advance stalled, the flag of the 23rd Ohio, made by his wife, “pushed on, and a straggling crowd would follow.” Federal officers on horseback were prime targets, but no one was immune from the flying lead. Among the seriously wounded was Colonel Duval, whom Comly saw carried off the field on a bloody stretcher. As the senior brigade commander, Hayes assumed command of the 2nd Division and Col. Hiram Devol of the 36th Ohio took over command of the 1st Brigade.

Hayes’ horse was freed from the slough and he was soon re-mounted on the mud-caked beast; miraculously, Hayes was not scratched during the battle. At the Yankees’ approach, the Rebels at the Hackwood farm retreated in disorder toward Winchester to the southwest, pursued by Federal cavalry with flashing sabers. Upon gaining the second stone wall, the men of the 23rd flopped on the ground in utter exhaustion. Hayes reported, “No attempt was made after this to form lines or regiments.”

At the same time that the 2nd Division swarmed across Redbud Run, Thoburn’s 1st Division charged out of the woods into the remainder of Gordon’s Confederates. The battered XIX Corps refused to advance, much to Thoburn’s ire. The tangled woods had disorganized his line so that “all technical order was gone.” Events on the 1st Division’s front proceeded similarly to the 2nd Division’s fight, and soon the two jumbled halves of the VIII Corps were fighting side by side. Thoburn reported, “I have never witnessed more zeal and daring than was here displayed.” To add to Early’s consternation, off to the south, the VI Corps pitched into the Confederates along the Winchester-Berryville Pike. A Confederate sergeant facing Crook’s men recalled, “Here the hardest fighting of the day took place.

Hastings recorded that Crook’s two divisions were “but a mob,” and soberly looked over his shoulder to see that “hundreds of our colleagues had gone down; some in the hills beyond Red Bud [Run], others in the morass and about Hackwood House. Our line was too weak and exhausted to venture on.” Having spent itself in the charge, Crook’s men temporarily rested behind the stone wall they had taken from Gordon’s graybacks. Artillery shells continued to explode all around, some of them hitting the stone wall and scattering stones around. It seemed to the 23rd’s commander that “men are dropping all about … like leaves in an October storm.”

Comly recalled that Crook was present with Hayes’ Division, “as cool as if he were sitting at home … riding up and down the line, saying nothing, but [by] his presence somehow charging the men with electricity.” Hayes’ conduct also impressed Comly: “He is everywhere—exposing himself [to fire] recklessly, as usual.”

Hastings, realizing how hungry he was—no one in the division had eaten since before dawn—saw the colored cook who served Hayes’ staff jogging across the field from the direction of the XIX Corps, “loaded down with haversacks, tin cups, and a large pot of coffee.” The famished officers eagerly consumed the unexpected victuals.

The finely aligned ranks of the XIX Corps finally emerged from the tree line far in the rear of Crook’s men. The surgeon of Hayes’ brigade, Doctor Joseph Webb, was tending to the wounded behind the front line when a XIX Corps’ staff officer, impressed at the spectacle of his unit’s march, reined in near Webb and exclaimed, “See how the glorious XIX Corps comes up in perfect order!”

The surgeon sarcastically replied, “Yes, and I’ve been gathering the wounded of my corps from this field for the past half-hour.”

Several hundred yards south and west of the VIII Corps, the Confederate line was reorganizing. While Gordon rallied his men, two brigades of Wharton’s Division came up in support. Hastings lamented, “It was a mistake to stop at the stone wall even for the few minutes that we did.” After a short while, at 4:30 p.m., Crook ordered another charge. The men of the 23rd Ohio rose and, following Comly, clambered over the remains of the stone wall and charged across the field at the double-quick. The regiment’s line quickly came apart as the men increased speed to a run in an effort to cover as much ground as possible before the Rebel infantry could reload. After firing a few volleys, the Confederates retreated as “a mob” as Torbert’s cavalry swooped in to scoop up prisoners. The main body of Gordon’s and Wharton’s men retreated a half-mile, to the very outskirts of Winchester, where they reformed. Years later, a member of the 23rd exclaimed, “What stubborn fellows Gordon and his men were!”

Following Hayes’ orders, Hastings rode to the far right of the division to scout the new Confederate line. As he cleared a clump of bushes, he “came in full view of a long line of the enemy, not far away, lying in a farm ditch. This line opened on me and the bullets hummed like bees.” Hastings turned his mount and rapidly rode away. Just before he reached cover, however, a bullet slammed into his right leg near the knee. He wrote, “The sensation was that of being struck by a club, without pain.” Hastings rode back to Hayes to report, and the colonel quickly sent him to the field hospital in the rear where he arrived, “sick and fainting.” Crippled for life, Hastings would never rejoin Hayes or the 23rd Ohio; his military career was over.

The new Confederate position was Early’s last ditch and his men knew it. From the new line, a stout fire of musketry and artillery was kept up against the bluecoats 400 yards away. Immediately behind the 23rd’s line, Comly hugged the ground on the crest of a slight elevation, together with Lt. Col. Benjamin Coates, who now commanded Hayes’ 2nd Brigade. Comly remembered, “A continual shower of bullets pelted the ground all around, until it did not seem possible to live a moment there.”

At this point, two “old veterans” of the 23rd Ohio succumbed to the temptation to loot the bodies of several dead and wounded soldiers barely 20 feet in front of the regiment. The two men stood up under the heavy fire and walked “as cool as mules” in front of the main line, looking for, as Comly termed it, “unconsidered trifles.” The two men had evidently been doing this all through the battle as one had “a well filled knapsack on his back.” To present as small a target as possible, the two looters walked sideways to the Rebel line. As Comly and Coates watched, a Confederate artillery shell struck the looter’s “well filled knapsack” and sent its contents flying. “Neither of the men was hurt a particle, but the man whose plunder was so unceremoniously squandered, scrambled up from where he had fallen, perfectly beside himself with rage.” In full view of the Confederates, the man “jumped up and down, shrieking and shaking his fist at the enemy and swearing a perfect stream of the most horrible oaths I have ever heard.” The men of the 23rd Ohio “all laughed at first, but the swearing seemed to strike them as unsuitable at the time and they began yelling at [the looter].” Comly finally ordered the man back into ranks, where he “quieted down.”

Soon after, as bullets continued to shower around them, Comly saw Coates “working himself slowly around on his stomach like a pivot” until his head faced away from the Confederate line and his feet toward the enemy. Comly asked if he was wounded, to which Coates replied in the negative and continued, “I’ll tell you what it is, Colonel. I’m a doctor, I’ve studied anatomy some; I know the vital parts are at the upper end of the body; and it strikes me that the other end is the proper one to present to the enemy while we wait here under such a confounded fire as this.” The two officers then “burst out laughing, as it seemed excrutiatingly [sic] funny.”

One Confederate artillery battery, positioned in plain sight without cover, seemed to have the particular range of the 23rd Ohio. Comly ordered the 23rd’s Lieutenant McBride to take some members of his company, which was armed with 0.71-caliber Saxony rifles with a range of 1,200 yards, to the top of a nearby knoll to kill off some of the battery’s horses. McBride and his men “crept up [the knoll] like Indians, covering themselves by the inequalities in the ground.” Comly recalled, “At the very first shot a horse dropped. Almost as soon, another [animal] was dropped. A panic seemed to seize the artillery, and they commenced to hurriedly limber up.” The swift departure of their supporting guns unnerved the Confederate infantry.

As soon as the battery departed, Comly recalled, “Our whole line then rose with a tremendous yell, and the men all rushed pell mell for the [Confederate] breastworks.” One of the Confederates on the receiving end of the VIII Corps’ charge admired, “They advanced in splendid order.”

Comly continued, “And then, without stopping to fire another shot, the enemy ran, in utter confusion.” Led by McBride’s company of sharpshooters, the 23rd Ohio scooped up approximately 200 prisoners in the charge.

Then came the coup de grâce, as Torbert’s cavalry, with the division of the flamboyant George Custer in the lead, swooped down upon the fleeing Confederates in a thundering mounted charge. The breaking of the lines of Gordon and Wharton by the VIII Corps was like opening the floodgates of a dam as, one by one, the units in Early’s line collapsed and the panic-stricken Rebels fled through the streets of Winchester and south down the Valley Pike.

A friend of Comly’s who was in Custer’s cavalry reined in next to him and, flushed with victory, “stooped down over his horse’s neck and threw his arms around me and kissed me, shouting, as if he was out of his head, ‘Isn’t it glorious!’” The Confederate stampede ended the battle. Hayes aligned his division and marched it into the streets of Winchester—it was the first Union unit to enter the town. In a column of fours, the 23rd Ohio entered Winchester from the east and marched to the center of town, where they turned south and tramped down the Valley Turnpike. Hayes placed them into camp along the pike just south of the town as darkness fell.

The 23rd Ohio paid a high price for its valor that day, losing 67 men (nine killed, 40 wounded, and 18 missing). Going in with a much smaller number than the other Federal corps, Crook’s command suffered approximately 800 casualties, while total losses for Sheridan’s entire army amounted to 5,000 men; Early’s hard-pressed Confederates lost 3,700 men, of whom over 2,000 were prisoners. It was the first time in the war that Early’s men—Stonewall Jackson’s old command—had been put to ignominious flight.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments