By Norman Herz

The year 1944 dawned with America already at war for over two years. In an event not marked by history books, the 96th Navy Construction Battalion, Seabees, crossed the Atlantic from Davisville, Rhode Island, on the Abraham Lincoln, a converted banana boat escorted by two destroyers, the USS Ellis and USS Biddle. Three days later, on January 4, the 928th Engineer Aviation Regiment left Hampton Roads, Virginia, in three ships, the Liberty ship John Clarke and LSTs 44 and 228, as part of convoy UGS-29 officially headed to the Mediterranean. In the records of the 10th Fleet the ship movement card for the John Clarke shows departure from Hampton Roads on January 5, 1944, due Gibraltar January 22. Gibraltar is crossed out and Terceira is written on the line below with an expected arrival date of January 17. Apparently, not even the captain of the John Clarke knew he was going to the Azores until his ship was well out to sea. Each outfit was equally ignorant of where it was going and of the other’s existence, but they were soon to join up on a secret mission—Operation Alacrity—planned in meetings in Casablanca, Canada, and Washington by the Allied chiefs of staff with the collaboration of their leaders, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. It would be one of the most audacious events involving Portugal during WW2—if, that is, it ever got off the ground.

The Coveted Azores Gap

Both the Axis and the Allies wanted to get the Azores first, and each had their own ideas on how to do it. Operation Alacrity was Churchill’s; Roosevelt had Task Force Gray and Operation Lifebelt, and Operation Felix/Projekt Amerika was Adolf Hitler’s. Each side probably knew of the other’s plans, and each had the same goal in mind: to occupy the strategically located Azores archipelago by fair means or foul, by diplomacy, intimidation, or outright armed invasion.

Controlling the islands with their strategic position in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean meant for the Allies protecting the important convoy routes of the central Atlantic. Failing to control them left a giant “black hole” in the Azores Gap for convoys headed to the Mediterranean and the United Kingdom, a gauntlet with waiting U-boat wolfpacks, an unhappy shooting gallery of Allied troop and supply ships. If an invasion of Europe was to take place, the Azores Gap had to have air cover. Only an Allied airfield in the mid-Atlantic could provide that cover.

The Azores, a group of nine volcanic islands belonging to Portugal and lying in the central Atlantic, cover an area of 910 square miles (2,355 square km), or slightly less than Rhode Island. They stretch over 373 miles (600 km) from Corvo in the northwest to Santa Maria in the southeast, with Santa Maria closest to Europe, about 930 miles (1,500 km) from Lisbon. Flores, the farthest and considered the westernmost point of Europe, is 1,100 miles (1,770 km) from Labrador and 2,240 miles (3,600 km) from the East Coast of the United States. Even before America’s entry into the war, President Roosevelt thought he could justify American intervention in the Azores by calling them easternmost North America and thus falling under the protection of the Monroe Doctrine.

For Germany, the Azores represented a base for U-boat operations plus air bases needed for Projekt Amerika, a Luftwaffe bombing campaign of America’s East Coast cities. With a base for provisioning in the middle of the Atlantic, U-boats would not waste so many days and precious diesel fuel sailing out of and returning to their pens in France. Their time in action would become almost unlimited.

“The U-Boat Attack Was Our Worst Evil”

A problem for all these schemes was that Portugal during WW2 was a strict neutral, and had no desire to get involved in a conflict between the great powers, firmly believing that when an elephant sneezes a mouse dies of pneumonia. To stay out of the war, Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio de Oliveira Salazar did not want either side to use his territory as a base for offensive operations.

The Allies agreed on one thing. World War II would not be lost on any land battlefield but might be in the ship graveyard of the North Atlantic. Churchill wrote, “The U-boat attack was our worst evil. It would have been wise for the Germans to stake all upon it.”

U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull said, “Our whole democratic civilization twice hung by a thread during the recent war—once during the summer of 1940 after Dunkirk and the fall of France, when Britain even with her Navy might have failed to repulse a full-scale German attack across the Channel, and again during 1942, when German submarines were sinking three Allied merchant vessels for every one constructed.”

In 1941, Admiral Karl Dönitz’s U-boat wolfpacks sank 2.1 million tons of shipping, while submarine production was increasing from 65 to 230 a month. Ships were destroyed faster than they could be replaced. Over 3.5 percent of the tanker fleet was lost each month. To win the war, the sea lanes had to be protected and that could be accomplished only by long-range bomber patrols flying from air bases on neutral territory around and in the Atlantic. For the northern sea routes, Denmark’s Greenland and Iceland would provide that protection, and for the broad expanse of the central Atlantic, Portugal’s Azores Islands were the only possibilities. The German wolfpacks had to be contained if American convoys were to bring their precious cargoes of men and matériel into the war.

Combatting the U-Boat Menace With Air Power

The outlook for the free world in 1941 appeared bleak, but by 1943 the Allies had constructed airfields along the northern perimeter of the Atlantic in Newfoundland, Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom so ships following an extreme northerly route had aerial protection.

The bases in Greenland were made possible by an agreement signed on April 10, 1941, between the United States and Henrik de Kauffmann, recognized as the legitimate Danish ambassador by Washington but not by Copenhagen, then under German occupation. Since the United States was not at war yet, Roosevelt called on the Monroe Doctrine to justify the action, loudly protested by Hitler as an outrageous violation of neutrality.

After Iceland declared its independence from Denmark on July 7, Roosevelt sent Naval Task Force 19 made up of the Marine Corps 1st Brigade accompanied by four battleships, 13 destroyers, and eight supply ships, or more than the entire German fleet in the Atlantic, to Iceland to relieve a small British force. Once again Hitler expressed dismay that a professed neutral could take such belligerent actions. German newspapers howled, “Invasion of Iceland; Roosevelt provokes war; Arm-in-arm with Bolshevik mass murderers; Roosevelt has irrevocably torn up the Monroe Doctrine.”

Air bases were built, making the entire northern perimeter of the Atlantic more secure for Allied convoys, alleviating but not eliminating U-boat attacks on England- and Russia-bound convoys. Dönitz then moved his submarine patrols from the north to the Azores Gap where no protection was possible in the vast expanse between Bermuda and Gibraltar for ships headed to North Africa and the Mediterranean. Convoys sailing to Morocco, Tunisia, and Italy from the United States and tankers from Caribbean oil fields had to sail directly through the middle Atlantic without aerial protection.

Operation Felix

There was no other recourse: an air base had to be established in the Azores Gap or convoys could continue to expect U-boat attacks. The four convoys—UGS 4, 5, 6, and 7—to sail from New York and Hampton Roads, Virginia, to the Mediterranean from January 13 to April 1, 1943, lost 13 ships with an aggregate tonnage of 83,500. To resolve the crisis, the Allies had to confront Portugal and convince the country that cooperation was in its best interests, especially since eventually Portugal would need help recovering East Timor, its East Indies colony, from the Japanese.

However, Prime Minister Salazar was justifiably frightened by the threat of a German “protective occupation” of his country if he allowed the Allies to build an air base in the Azores. It was obvious to him as well as to the combined chiefs of staff that if the Germans invaded Portugal overland from Spain there was not a solitary thing the Allies could do to help the small, underequipped Portuguese armed forces.

While the Allied leaders were working out a strategy for the Azores, Hitler was formulating plans for world conquest. After the blitzkrieg through Poland, France, and the Low Countries, the next step was to be the invasion of England, but after the RAF shot the Luftwaffe out of the sky in the summer of 1940, that operation was aborted.

Debate in the German high command then narrowed to two choices for the next campaign, Operation Barbarossa against Russia or Operation Felix, the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula—crossing Spain to seize Gibraltar and Portugal, then North Africa and the Spanish and Portuguese Atlantic islands. Hitler chose Barbarossa but promised the admirals that the defeat of Russia would take only a few months, after which attention would be turned to Felix.

D-day for Operation Felix was to be January 10, 1942. German bases in the Azores would provide, first, a port for U-boat support and, second, an airfield to base the new Messerschmitt long-range bomber, the Me-264 Amerika. The plane carried a 4,000-pound bomb load with a 12,600 km (9,000 mile) operational range, far enough to attack northeastern American cities from Boston to Washington and return.

Operation Felix must have been known to the Allies as well as to Generalissimo Francisco Franco of Spain, who was kept well informed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr, German military intelligence, and an avowed anti-Nazi. Salazar also must have been told of the German plans by Franco, which surely gave him many sleepless nights and weighed heavily in all his decisions. If he gave in to the Allied demand for bases in the Azores, Hitler would go ahead with Felix and invade the Portuguese homeland.

Planning an Allied Protective Occupation of the Azores

Despite Portugal’s refusal, in August 1941, even before America entered the war, Churchill and Roosevelt decided at the historic Newfoundland Conference to build an air base in the Azores by any means, including armed invasion. Approved at the conference, Operation Pilgrim would neutralize German threats to Atlantic shipping and the Iberian Peninsula. The British would seize the Canary Islands, and the Americans would provide “protective occupation” of the Azores. American justification for such action as an allegedly neutral power was the Monroe Doctrine, which Roosevelt invoked after placing the Azores firmly in the Western Hemisphere, a move deplored by his geographers.

In May 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill met in Washington to discuss war strategy. The decision was made to occupy the Azores with or without the permission of Portugal during WW2. The operation was supposed to be accomplished as delicately as possible.

General Hastings Ismay, an adviser to Churchill, reported, “The Combined Chiefs of Staff had no difficulty in reaching agreement on a number of points, such as the prosecution of the U-boat war, the bombing of Germany, and the occupation of the Azores. The last-named was a delicate problem. Both the Americans and ourselves were anxious to have a base on that island [sic] for operating the long-range aircraft which were employed in giving cover to our convoys and dealing with the U-boats, but there seemed little hope that Portugal would grant this concession of her own free will. It was therefore agreed that the British should mount a small expedition to capture the island at an early date, it being understood that this must be done without the use of violence. It is easy for high authority to make that sort of stipulation, but the unfortunate commander may easily find his attempts at seduction are unavailing and be compelled to have recourse to rape.”

The British 247th Air Group, the American 928th Engineer Aviation Regiment, and the 96th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees) were charged with accomplishing the task.

The Windsor Treaty of Eternal Alliance

Cooler heads convinced Churchill to exhaust diplomatic approaches before going ahead with an armed invasion. Their strategy was to call upon the Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 1373 for “mutual friendship and defense” signed by Edward III, King of England and France, and Don Fernando, King of Portugal, and Queen Eleanor to argue the case for an Allied base. The Windsor Treaty, the oldest of its kind still in effect between any two nations today, called for either party to aid the other in case of war as long as such assistance could be provided without great injury to the signatory’s country. It had been invoked several times in the past, notably during the Peninsular Wars, when Napoleon invaded Portugal and Spain only to be defeated by a British army under the Duke of Wellington, and earlier during Elizabethan times when British “retribution pirates” attacked Spanish galleons returning from the New World ostensibly to avenge Spain’s seizing the throne of Portugal in 1570.

On October 12, 1943, Churchill revealed to the House of Commons that he had called upon the Windsor Treaty of Eternal Alliance with Portugal to authorize an operation to protect the Azores. The treaty, said Churchill, was invoked with the approval of Salazar, and Operation Alacrity was beginning. Churchill relished every moment of the historic event, taking great pleasure in springing on a surprised Parliament a treaty that few even knew existed and talking of places of which none had ever heard.

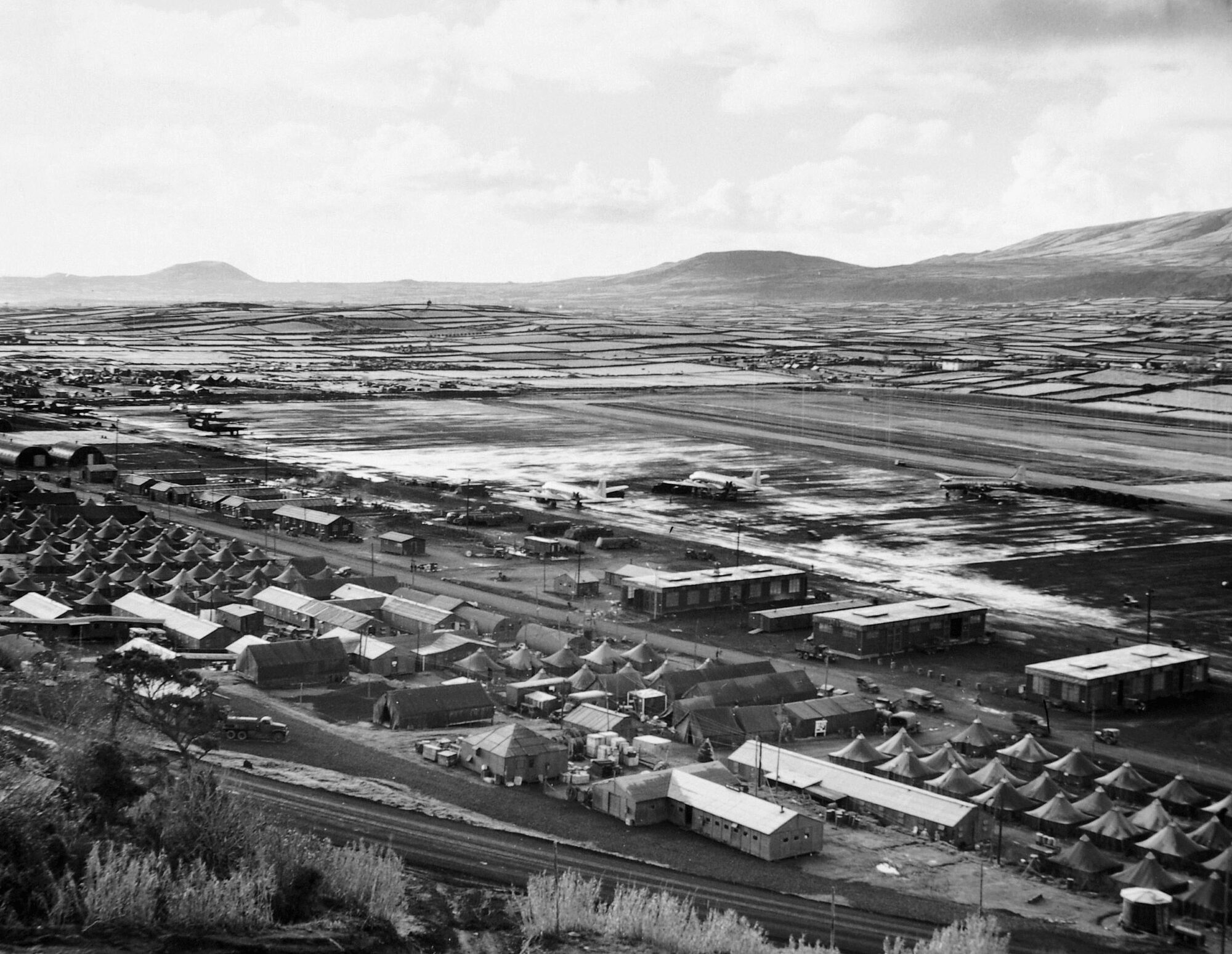

To preserve the secrecy of the operation, a newly formed task force, the 247th RAF Air Group commanded by Air Vice Marshal G.R. Bromet, sailed in three small convoys from Liverpool on September 30, arriving on the island of Terceira in the Azores on October 8, four days before Churchill made his startling revelation to Parliament. The task force numbering some 3,000 officers and enlisted men drawn from the Army Sappers (Royal Engineers), RAF, and Royal Navy immediately began construction of the air base.

The British worked quickly to construct a temporary airstrip. Normally 60,000 pierced plank steel mats were linked together to form an all-weather surface 5,000 feet long by 150 feet wide, adequate to serve as an advance runway for most tactical operations. However, this was not to be an advance runway but a full-fledged airfield that expected heavy use from transport and bomber aircraft, so a 6,000-foot- long runway was constructed at Lagens Field. On November 9, the first kill was registered when a surprised U-707 was sunk by an RAF bomber based at the new field.

Admiral Dönitz’s submarine fleet had been using the Azores for provisioning. Years before the war, German intelligence had organized a worldwide naval supply service, the Etappendienst, designed to serve the warships they planned to keep at sea in the coming conflict. One of the principal stations of the network was in the port of Horta on the island of Faial in the Azores, where agents were ostensibly working for a German shipping line whose cargo business had dried up during the war. With the Azores interdicted by the new RAF airbase, another spot for the U-boats to rendezvous was desperately needed, but with the Atlantic now covered by Allied patrols that would prove impossible.

Americans Unwelcome in the Azores

At the Washington Conference, the Allies had agreed that the British would enter the Azores first, to be followed in two weeks by American forces. The British might come in under the 1373 treaty, and the Americans would follow according to the provision in the treaty that Britain and Portugal would be “friends to friends.” American engineering know-how was needed to build an airfield capable of handling the heavy traffic expected for the coming liberation of Europe and, more immediately, for increased submarine patrols by long-range bombers.

As reasonable as these arguments appeared to the Allies, Salazar was not buying any of them. America was not a signatory to the 1373 treaty, so he had no excuse of diplomatic necessity to fall back on if the Germans pressed him to explain this action. Even though there was almost no chance of an attack—German troops had been driven out of North Africa and were on the defensive in Italy and Russia—the Portuguese dictator was still fearful of some kind of retribution by Hitler. Unrestricted submarine warfare against Portuguese merchant ships or aerial bombardment of its cities were both still possibilities.

Salazar threatened to forcefully resist any landing of American troops in the Azores but was convinced only hours before the Seabees showed up to accept the fact that they were coming with or without his permission. Negotiations had continued into the early morning hours in Lisbon, with cables flying between London and Washington. The talks ended shortly before the Seabees arrived at 9 am on January 9, accompanied by two destroyers with enough firepower to overwhelm anything on the island.

The most delicate negotiations probably took place on Terceira where the Seabees were hoping to land. The Portuguese commander, Brigadier Tamagnini Barbosa, had orders from Salazar, which had not been rescinded as far as he knew, to resist any “American invasion.” Bromet convinced Barbosa that the Americans would be under British command and so should be considered part of the British forces on the island. The Portuguese troops stayed in their barracks, and the critical American contribution to Operation Alacrity began.

Building American Airfields

The American engineers landed a week later without the threat of resistance but unfortunately accompanied by a storm, which snapped an anchor chain and drove their landing ship onto a rocky beach. Equipment and supplies were ruined and had to be replenished in a subsequent convoy.

The American forces built up the port facilities, including services for offloading aviation fuel; constructed all-weather runways, roads, buildings, and water and fuel storage tanks; and generally made sure that Lagens Field was ready to handle any increased air traffic. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were pleased with the rapid progress and that the field was fully operational in a short period of time. However, there was no distinctly American airfield in the Azores.

Another airfield was needed for two salient reasons. First, Lagens was shared with the British who were the official landlords of the base, and, second, a backup base would be required for the heavier traffic expected for the invasion of Europe and to speed traffic to the Pacific Theater. Negotiations were intense with Salazar to obtain such a base and resulted in a compromise: the Americans could construct a civilian field ostensibly run by Pan American World Airways primarily for civilian use. It would be turned over to Portugal at the end of the war.

Before an agreement was reached, a team of engineers from the 928th was assembled at Lagens to start the survey work. It was obvious that both time and the patience of the Joint Chiefs had run out; an American air base would be built no matter what the diplomats did. Passports were issued identifying the men as engineers employed by Pan American World Airways, and the team was to travel to the island of Santa Maria to start building the American airfield.

A briefing team from U.S. Army Intelligence was flown to the Azores from Washington. Team members warned the engineers to strictly maintain their civilian cover, and they cautioned that if they were discovered to be American military the Portuguese could consider them spies.

In August 1944 the team sailed aboard a Portuguese inter-island ferry of the Imprêsa Insulana de Navigação from Terceira to Santa Maria. The engineers, with construction by local labor, laid out a temporary earthen emergency landing strip in a matter of weeks. A planned permanent 11,000-foot airstrip, which was to be the longest in the Atlantic Ocean, and structures necessary for the airfield were staked out. The actual building of the airfield would theoretically take place when Salazar gave his approval. On November 28, soon after approval was granted, the Santa Maria air base became legal as well as fully operational.

450 Heavy Bombers Transfered Through the Azores

During the summer of 1945, more than 450 heavy bombers flew to the United States via Santa Maria and the Azores route for reassignment to the Pacific Theater. After the successful conclusion of the mission to Santa Maria, Brig. Gen. Cyrus R. Smith, who led Military Air Transport Command, commended the enlisted men involved and appointed several to Officer Candidate School. Preserving the secrecy of the mission, the author’s commendation reads, “He at all times performed assignments willingly and in a superior manner. His attitude, efficiency, conduct and bearing, both while working and in contacts with the local populace, tended toward the success of this detail.”

Lagens Field, now called Lajes, has become an important link in the defense networks of the United States and NATO. It has seen service in many overseas operations beginning in the Cold War with the Berlin Airlift and including the Persian Gulf.

The Crucial “Overseas Mission”

Although Operation Alacrity is conspicuously missing from official and unofficial histories of World War II, the Azores Islands clearly played a key role in winning the war in the Atlantic. The final “Report of the United States Naval Facilities in the Azores” states, “Allied acquisition of the Azores as a base was a decisive blow against German submarine warfare. This little cluster of Portuguese islands, two thirds of the way between our east coast ports and Gibraltar, when coupled with Bermuda and Newfoundland, put the North Atlantic convoy route within range of land-based bomber protection over the entire transoceanic journey…. Land-based planes in anti-submarine warfare were … menaced only by opposing aviation … and most important of all, the number of planes that could be sent into the air from our new mid-ocean landing field far exceeded that which could be sent up from any carrier group.”

The secrecy surrounding Alacrity was pervasive and long-lived. The authoritative history of the Army Air Forces in World War II cites the role played by each Aviation Engineer regiment, but without even a hint of the existence of the 928th.

A visit to the historian of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers shed no more light but was very revealing for what was not there. In the files at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, The Narrative History of the 928th Engineer Aviation Regiment begins, “The unit having completed its overseas mission returned to the United States 10 March 1945 … for 30-day recuperation leave and furlough while en route from the Port of Entry (Hampton Roads, Virginia), to Geiger Field, Washington.”

There is no mention of what “its overseas mission” had been, not a hint of where it was or why, but it was clear that the mission was too secret to entrust to the Corps of Engineers historian. Records of Operation Alacrity buried away in the Seabee historians office in Port Hueneme, California, and the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, were declassified 20 to 30 years after the end of World War II.

The mysterious “overseas mission” of the 928th Engineers was also documented in five large boxes in the files of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and two boxes of State Department records. They contain enough information to piece together the story of the Azores bases. Finally revealed were the high-level military decisions and diplomatic maneuvering and the adventures, misadventures, and accomplishments that led to the Allied mission to the Azores. Now, finally, the complete story of Operation Alacrity could be told.

I’ve been searching for my fathers Army WW2 records. The NPRC told me his records were destroyed in the fire of 73. My father died in 95. Growing up he told me about crossing the Atlantic on a ship, going through a bad storm at sea. He also said he was stationed on the Azores and that he had some heavy trucks and a crew of Portuguese assigned to him. So reading this was gave me some insight to at least some of what he did. There are still questions, was he on the SS John Clark, did he pretend to be with Pan Am ?? Thank you so much for the work, research and sharing this story, It had meant so much to me.

James,

My father was on the Azores with the 801st Engineer Aviation Battalion, which was attached to the 928th Engineer Regiment. They constructed the airbase at Lagens Field. He helped produce the battalion history which I posted as a Website, http://www.skydozer.com.

It lists six men named Miller in the battalion: James, from Denver City, Texas; Carl, from Randolph, Oklahoma; Howard from Lubbock, Texas; Joseph from Los Angeles, California; Milburn, from Path Fork, Kentucky, and Walter from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Although the 801st does not represent all of the men in the regiment it is the majority, as the 928th was primarily a headquarters company and was unique among Engineer Aviation Regiments in WWII for only having one battalion attached (the 801st). This was for the particular mission to the Azores.

There’s a lot more information on the website. I hope this helps.

Steve, Its November 11, 2021, Veteran’s Day and the most appropriate day to contact you in remembrance of our fathers and all those who served our Country. God bless them. My father was part of Army Engineers 801 in Portugal, Santa Maria Island. For quite a while now, I’ve had this great desire to share his stories and pictures of his time in Portugal. I found your website several months ago and was so taken with the time you given to document your father and his service to our Country and the world. Like your father, my father was a great storyteller and I’ve always wondered what was true and what was fiction. Your website gave such validation to stories he told me. Not only that, but after his death in 2009 at age 90, I found a photo picture book in our attic of his time in Portugal. The pictures are stunning and in pristine condition. There was also an envelope with his military documents…enlistment confirmation, honorable discharge, etc. What burns in my heart is that my father was born in Mexico in 1919. He came to Los Angeles with his family as a youngster. When the war came, he didn’t hesitate, he enlisted. Off to training in Maine, then on to the Islands. He always spoke of Terceira and the sound of horse hoofs on cobblestone roads…beautiful memories of his story telling for me. When his service ended in 1946 and it was time for him to return, there was one problem. He was not naturalized or a citizen of the United States so he could not enter at New York. And that’s where my heart goes…in his documents are 4 Affidavits signed by 4 of his fellow-servicemen attesting that my father would be a “good American citizen if naturalized”. My father was naturalized and became a United States citizen. These men are a part of my life and I so want to thank them and share what I can with their families. I’d love to collaborate with you and bring these special pictures and memories to others. I look forward to hearing from you. (I tried to use the “contact us” option on your website, skydozer, but the email option doesn’t work for me…glad I found you here.) Laura

The aircraft in the background of the evacuees is a Douglas C-54 Skymaster.