By Kevin Seabrooke

On the night of September 16, 1776, young Nathan Hale, a captain in the Continental Army, set out across Long Island Sound from his native Connecticut on the armed sloop Schuyler. The former school master was to land at Huntington Bay, Long Island, and walk some 50 miles to British-occupied Brooklyn to gather information on troop movements.

Details of Hale’s movements in and around New York after this remain sketchy to this day, but one immutable truth remains—he would be dead within a week, hanged as a spy.

And though he never saw combat, Hale displayed such courage and commitment in surrendering his life for his country that, long after his death, his name and final words have come to embody American patriotism itself.

As the first American executed for spying on behalf of his country, Hale is considered the patron saint of American intelligence. A statue of him stands in CIA headquarters with the words “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country” circling its base.

Yet there are no official records of anything Hale may or may not have said.

British Lieutenant Frederick Mackenzie recorded in his diary on the day of the execution that Hale acted “with great composure and resolution, saying he thought it the duty of every good Officer, to obey any orders given him by his Commander-in-Chief; and desired the spectators to be at all times prepared to meet death in whatever shape it might appear.”

It is generally accepted by historians that if Hale did utter those famous words, or anything close to them, he was probably paraphrasing a line from Cato, a play by Joseph Addison: “What pity is it / That we can die but once to serve our country!”

Addison’s play was a favorite of Hale’s and many of his fellow students at Yale.

Just a year and a half earlier another icon of the American Revolution, Patrick Henry, in a fiery speech to Virginia legislators urging the formation of militias is supposed to have said “Give me Liberty or Give me death!” Whatever his exact words, they are almost certainly another paraphrasing of Addison: “It is not now a time to talk of aught / But chains or conquest, liberty or death.”

U.S. Attorney General William Wirt, recreating the speech from eyewitness memories 40 years after the end of the war, attributed the phrase to Henry.

Though later scribes may have improved on these historical sound bites, it is of little importance, especially in the case of Hale.

The sentiment is most likely an accurate reflection of Hale’s state of mind. For, as he wrote to his father in 1775 regarding his decision to join the army, he felt that “a sense of duty urged me to sacrifice everything for his country.”

Washington learned of Hale’s death on September 22 when a group of Continental officers met with General Howe’s aide-de-camp Captain John Montresor under a flag of truce to discuss prisoner exchange. Montresor mentioned that a Captain Nathan Hale had been hanged as a spy.

Captain Tench Tilghman, Washington’s aide, wrote “General Howe hanged a Captain of ours belonging to Knowlton’s Rangers who went into New York to make discoveries. I don’t see why we should not make retaliation.”

But Washington was locked in battle with Howe, and the Continental Army did not publicly acknowledge Hale’s death. Only two newspapers of the day mentioned the execution of the young teacher as Hale’s fate was overtaken by other events.

The first version of Hale’s famous last words, “I am so satisfied with the cause in which I have engaged, that my only regret is, that I have not more lives than one to offer in its service,” came five years after his death.

victory of the war.

This was published in the May 17, 1781, edition of The Boston Independent Chronicle, as related by Hale’s friend and fellow officer Captain William Hull, who claimed to have heard about Hale’s execution from Montresor.

It was not until Hannah Adams’s 1799 A Summary History of New-England that the fate of Hale appeared in a lasting form of print and his story began to be more widely known.

Revolutionary services and civil life of General William Hull, published by Hull’s daughter in 1848, 23 years after his death, helped Hale’s story grow in popularity.

The absence of facts may be a factor in Hale’s endurance as a symbol of selfless love of country.

Hale was born in Coventry, Connecticut, in 1755, to Deacon Richard Hale and Elizabeth Strong, both from highly respected Puritan families in New England, Nathan was the sixth of 10 surviving siblings. At 14, he enrolled at Yale College with his older brother Enoch, 16.

Founded in 1701 by Connecticut ministers to train clergy, Yale College offered a spartan existence and a thorough grounding in religion, mathematics, science, and the classics.

When news of the fighting at Lexington and Concord had reached New London, Connecticut, on April 22, 1775, a militia was immediately formed and set off for Boston the next day.

Hale’s friends and Yale classmates, like Benjamin Tallmadge, were heading to Boston and he, too, was enthusiastic, reportedly crying “let us march immediately and never lay down our arms until we obtain independence.”

But Hale intended to honor a teaching contract that ended in July. On the 4th, he got a letter from Tallmadge (who would go on to lead Washington’s Culper Spy Ring) urging him to enlist.

“Was I in your condition… I think the more extensive Service would be my choice. Our holy Religion, the honour of our God, a glorious country, & a happy constitution is what we have to defend,” Tallmadge wrote.

On July 5, 1775, Hale accepted a commission as a lieutenant in Colonel Charles Webb’s Connecticut 7th Regiment. The rank was likely due to his Yale education at a time when only about one out of every 1,000 colonists had been to college.

In January, 1776, Hale had been promoted to captain and moved to the 19th Connecticut Regiment as part of Washington’s reorganization of colonial forces into the Continental Army.

Reeling from his defeat by General William Howe at the Battle of Long Island (August 27, 1776), Washington had retreated back to Manhattan, surrounded by water that the British Fleet could use to attack his army.

He knew the attack would come, the main question was where the Redcoats would land.

As Washington wrote to General Heath on September 5, 1776, “…every thing in a manner depends upon obtaining intelligence of the enemy’s motions…. Much will depend upon early intelligence, and meeting the enemy before they can intrench.”

In mid-August, Washington had promoted Major Thomas Knowlton, a veteran of the French and Indian War who had distinguished himself at Bunker Hill and the siege of Boston, to lieutenant colonel. Knowlton was ordered to select 20 officers and 130 men from the Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts regiments to form the New England Rangers to carry out reconnaissance and espionage missions along Westchester and the northeastern shore of Manhattan. When Hale was asked to join the Rangers, he jumped at the chance.

Later known as “Knowlton’s Rangers,” the Central Intelligence Agency, Army Rangers, Delta Force, and other such units trace their origins back to America’s first special force.

In early September, Knowlton asked for a volunteer to go behind British lines to report on troop movements on Long Island.

Three years out of Yale, 21-year-old Nathan Hale stepped forward eagerly.

First stationed at Winter Hill for the Siege of Boston, Hale had been in the army for more than a year, but had not been in a battle. His company had been building and manning fortifications on Manhattan during the Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, and did not participate in the action. Perhaps Hale saw the spy mission as an opportunity to do something useful for the cause of freedom.

Though no documentation exists, it is believed that Hale was the only volunteer on September 8, 1776. Later accounts of the events report Knowlton’s first choice as Lt. James Sprague, who refused, reportedly saying, “he was ready to fight at any time or place however dangerous but never could consent to expose himself to be hung like a dog.”

Hale’s friend Hull tried to dissuade him from going. Aside from the inherent dangers—if caught, he would be hanged—spying was considered at the time to be a dishonorable activity, beneath the status of a gentleman. But Hale reportedly countered that any task that was necessary for the “public good” was honorable.

As Hale crossed the sound, the British landed at Kip’s Bay on the East River (near what is now Midtown Manhattan) and though they were defeated at the Battle of Harlem Heights, they now held the lower part of the island.

It was Washington’s first success on the battlefield and it boosted the confidence of the Continental Army, but it had come at a price. Knowlton had been killed in the early stages of the battle on September 16. Ironically, the man who commanded America’s first “special forces” unit and the first to be executed as a spy would die within days of each other.

Hale’s cover story was that he was a Dutch teacher looking for work. A 1914 biography claims that not only did Hale not use an alias, he also carried on his person his Yale diploma with his name on it as his teaching credential.

The people of Long Island were in general supportive of the rebellion in private, but many Tories had fled there from Connecticut. There was a good chance Hale could see someone that knew him.

Though Hale’s mission was now moot, there was no way to get a message to him. When he learned of the events, Hale took it upon himself to go into Manhattan to try to gather information.

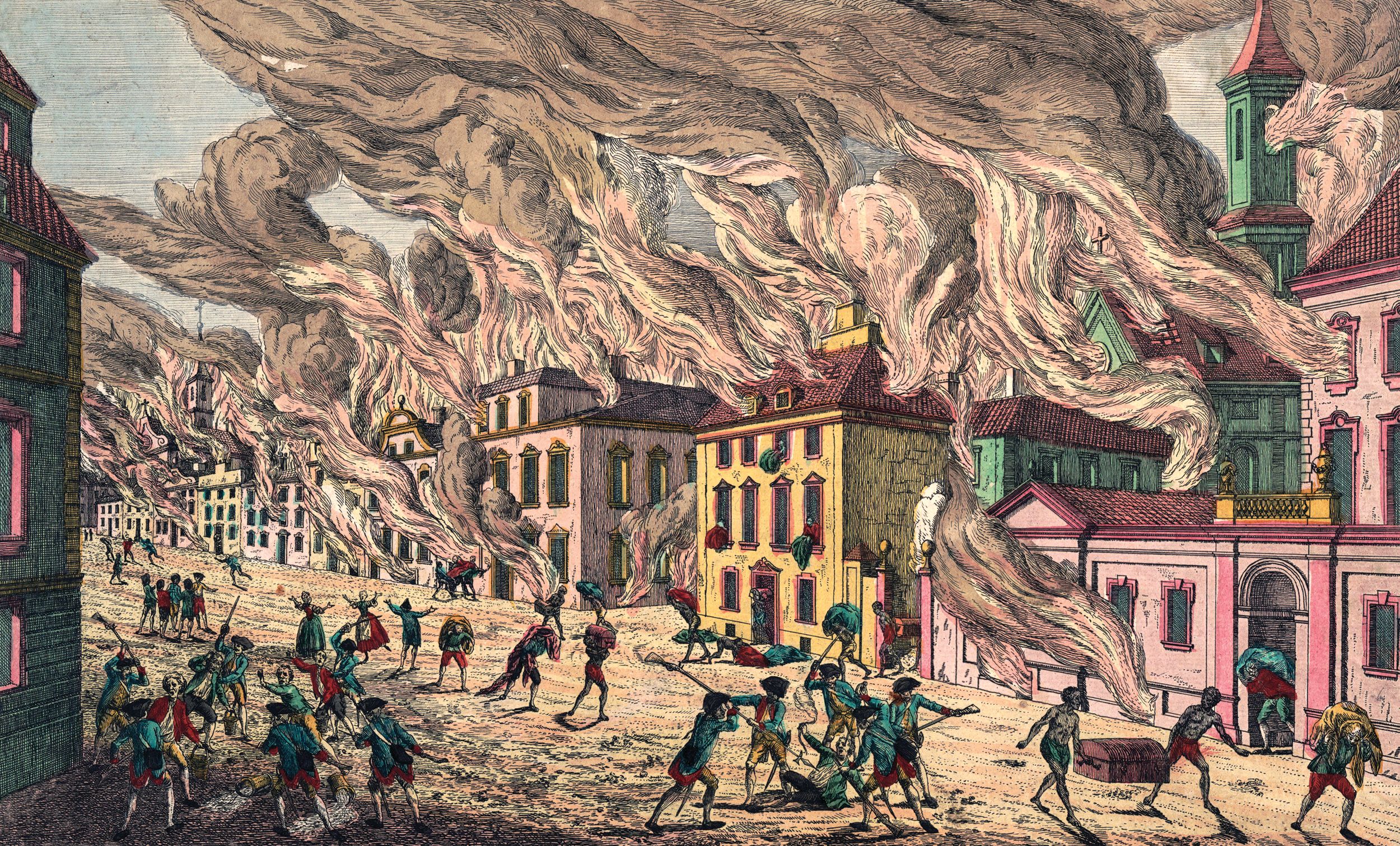

Returning from New York City, he was arrested on Long Island on September 21, the day after a fire broke out on Manhattan’s lower west side, burning some 20 city blocks. The British suspected arson and reportedly interrogated more than 200 suspects, but no charges were ever filed. There is no evidence that Hale was questioned or suspected of that crime.

A history of the American Revolution written by Tory Connecticut merchant, Consider Tiffany, came to light when it was donated to the Library of Congress in 2000. Tiffany’s narrative fits what little facts are actually known about Hale’s final days, but its veracity can’t be confirmed.

Tiffany wrote that Major Robert Rogers of the Queen’s Rangers “detected several American officers, that were sent to Long Island as spies, especially Captain Hale, who was improved in disguise, to find whether the Long Island inhabitants were friends to America or not. Colonel Rogers having for some days, observed Captain Hale, and suspected that he was an enemy in disguise; and to convince himself, Rogers thought of trying the same method, he quickly altered his own habit, with which he Made Capt Hale a visit at his quarters, where the Colonel fell into some discourse concerning the war, intimating the trouble of his mind, in his being detained on an island, where the inhabitants sided with the Britains against the American Colonies, intimating withal, that he himself was upon the business of spying out the inclination of the people and motion of the British troops.”

Hale believed he had found an ally, according to Tiffany, “one that could be trusted with the secrecy of the business he was engaged in; and after the Colonel’s drinking a health to the Congress: informs Rogers of the business and intent. The Colonel, finding out the truth of the matter, invited Captain Hale to dine with him the next day at his quarters, unto which he agreed. The time being come, Capt Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend, with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began the same conversation as hath been already mentioned. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Capt Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.”

No official record of Hale’s capture exists and his final words or thoughts are lost to history—he was permitted to write two letters, “one to his mother and one to a brother officer,” according to Montresor, but the letters were never delivered and presumed destroyed.

Additional theories and narratives of those final days exist, some have suggested Hale’s mission was sabotage and he was the one who set the Manhattan fire. Others have suggested Hale was on his third mission, not his first. One account has a Tory relative turning him in.

His body was reportedly left hanging for three days, as a warning to others, and then buried in an unmarked grave that remains unknown.

In 1846, a memorial was erected in Nathan Hale Cemetery in the Village of South Coventry, Connecticut.

The state legislature officially designated Nathan Hale as Connecticut’s state hero in 1985.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments