By Leila Levinson

Down in the basement of my father’s medical office a Nazi helmet stood guard. It sat on top of the pea-green Army trunk, CAPT R LEVINSON stenciled in white letters under a beaten-up leather handle. Throughout my childhood, whenever my father took me to the office while he did paperwork, I snuck down the basement stairs to stare at the trunk. It magnetized me, but I could not reach past the German helmet, with eagles on both sides grasping in their talons strange Xs that bent up at the ends at 90-degree angles. Only after my father’s death, when my brother, Alan, and I needed to empty the office, did I finally open the latches.

On top lay the dark green Army jacket my father was wearing in the portrait that hung in the family den. A Roman numeral “VII” within the shape of a seven-point star decorated one shoulder. An odd gold pyramid surrounded by blue adorned the other.

Under the jacket sat a Florsheim shoebox, big enough to hold boots. Out spilled photographs as I took off the lid. Hundreds of photographs. One showed endless ocean, faint ripples the only clue that the empty expanse was water, lit by a cloud-shrouded moon. My father’s seismographic handwriting noted on the back: “The English Channel, June 2, 1944. Prelude to the Invasion.”

Other photos showed GIs lying on the ground, white bandages on their heads, their arms, their thighs. Soldiers wearing Red Cross armbands. The Clearing Station on Utah Beach, Normandy, June 8, 1944. Huge circus-sized tents, emblazoned with enormous red crosses. Lines of GIs holding plates and cups. Mountains of rubble next to the remains of churches and homes. Fields covered in snow, tanks and bodies covered in snow. Fields covered with white crosses and occasional Stars of David. The boys who died in the Ardennes. Another: A lad in our battalion.

I flipped through the photos, repetitive with war’s destruction, until, at the bottom of the box, blurred stripes seized my eyes. Rows and rows of blurred stripes that cascaded into a wave. A foot emerged from the chaos, a leg. Many legs. Grotesque, frozen faces. My fingers pinched the top corner and turned over the photo. Nordhausen, Germany. April 12, 1945.

Nordhausen. What was Nordhausen? Another photo, more focused: a long canal-shaped ditch filled with bodies. Body after body, all in a row. An endless row of bodies. The burial of the concentration camps victims. April 15, 1945.

I dumped the photos back into the box and ran up the stairs, up and out into the hallway, the smell of rubbing alcohol relaxing my lungs, letting me breathe. I rested my forehead against the wall.

“Don’t Think it Can’t Happen Here”

“Those photographs were intense,” Alan said as we drove back to our family home. What were those photos doing in my father’s trunk? Why had he made notes on the back of them––as if he had been there––as if he had seen a concentration camp. But that wasn’t possible. He had told us (granted, just in passing, never with any details) that he had been a surgeon for the Army and had landed on Utah Beach right behind the first wave of troops on D-Day. He tended the wounded of the VII Corps all across France and into Germany, including the Battle of the Bulge. But he had never mentioned a concentration camp. He never talked about the Holocaust at all.

I first learned about the genocide of Europe’s Jews at age 15 when I went to the Jewish Community Center and saw a movie, Night and Fog, by Alain Resnais. It showed endless lines of people being marched onto trains, then behind barbed wire.

I ran home, trying with each breath to push away the images. I rushed into the den and poured out my anguish to my parents. My father responded, “Don’t think it can’t happen here,” as he wagged his finger before walking up the stairs and closing the bedroom door.

I might never have looked at the photographs in the shoebox again if my brother hadn’t shipped the trunk to me 12 years, a wedding, and two sons later. One afternoon, my sons came running into the house, “Mom, the UPS man is bringing us a trunk!” They hung over me as if I were opening a pirate’s chest. “Wow! Look at those buttons!” While they reached for my father’s jacket, I slipped the shoebox out of the trunk and under the couch.

By uncanny coincidence or providential design, my older son, Ray, was studying World War II and the Holocaust in his sixth-grade class.

“I can’t believe your dad fought the Nazis!” he said at dinner.

“He was a surgeon for the Army.”

“Did he see the Holocaust?”

My husband, Burke, turned and looked at me, waiting to see how I would answer. My tongue lay cemented to my jaw.

“I … I’m not sure,” I finally said.

That night I opened the shoebox and spread the photographs over my bed. The photographs of Nordhausen were blurred, the endless skeletal bodies staggering. My father’s hands had been quivering, I realized. He had been overwhelmed. He had seen the worst.

Two Weeks at Nordhausen

I learned that Nordhausen is how the GIs referred to the slave labor camp the Nazis called Mittelbau-Dora. A subcamp of Buchenwald situated three miles outside of the town of Nordhausen, its purpose was to produce the V-1 buzz bombs and V-2 long-range missles after the Allies discovered and bombed the testing facility at Peenemunde. The Nazis then transferred prisoners from Buchenwald and Dachau to Mittelbau-Dora, forcing them to carve tunnels through the Harz Mountains with hand chisels and dynamite. Then the prisoners had to live within the dank caverns and assemble the rockets.

When they could no longer work, the Nazis shot and burned them in a crematorium built at the camp once the bodies became too numerous to transport to Buchenwald. At the end of the war, not wanting to “waste” bullets, the Nazis built a warehouse called Boelcke Barracks on the far side of town. There they locked up the sick and weak prisoners and left them to starve to death. It was this warehouse, unintentionally bombed by the Allies two days before its liberation, that my father photographed.

“Oh, yes,” my Aunt Joan told me, “your father had the bad luck of being assigned to treat the survivors at a camp. It affected him terribly. He didn’t talk about it.”

Joan was a British “war bride” who met my father’s brother, Leon, in London during the war. Perhaps, I thought, he had revealed more to one of his siblings. I asked his 86-year-old sister, Mildred, what she knew about his time at Nordhausen.

“He spent two weeks there taking care of survivors,” she told me. “He had a nervous breakdown after seeing that place, and the Army sent him to the Riviera for R&R. We couldn’t understand why, six months after all the other boys were back, Rube was still over there. ”

Remembering the photographs in the shoebox of him on the Riviera, I was too stunned to ask more.

The Men Who Liberated the Camps

Books on the liberation of the camps do not address the quivering minds and hearts of the liberators, the consequences of bearing witness. But that is what I needed to know if I was to understand what the photographs might be telling me about my father. Perhaps they were clues to his steely silence, his melancholy and detachment.

The one way I could understand what the photographs were showing me was to find and talk with veterans who had also helped to liberate the camps.

I learned thousands of GIs had participated in the camps’ liberations. They liberated 39 camps, so if a division had 14,000 soldiers and one, if not two, divisions liberated each of those camps, tens of thousands of GIs witnessed them.

In the spring of 2007, in the former Eastern bloc, researchers discovered Nazi documents that established the existence of hundreds of subcamps for each of the listed camps. So, once subcamps are factored in, the total number of camps increases to more than 5,000, placing the GIs who witnessed a camp in the range of 250,000, especially if the number includes auxiliary troops like my father’s medical battalion that were brought in to help survivors. In addition, General Eisenhower ordered soldiers from every battalion within 50 miles of a discovered camp to send soldiers to be witnesses. He had the prescience to anticipate “Holocaust deniers” and wanted as many eyewitnesses as possible to view the horrors of the death and concentration camps.

Through luck and persistence, I identified and located 42 men and one woman who had been GI liberators and wrote them letters requesting interviews. Within 10 days I had set up 10 interviews for the end of the summer, when my family and I would be driving back to Texas from northern New York State. My husband and sons agreed that we would extend the return trip so we could stop along the way for my interviews all along the Eastern Seaboard. I did not anticipate how having my family with me and how concentrating the interviews within a 10-day span would intensify my response to meeting the veterans and what they would tell me. Because, even though I taught a course on literature of the Holocaust to college students, I was unprepared for the stories I heard and the emotions I saw.

“It Was as if I had Entered Hell”

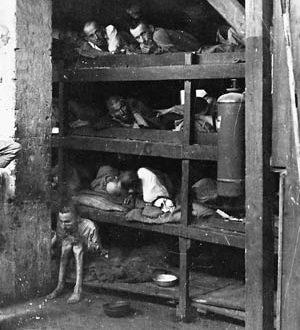

“It was as if I had entered hell,” George Kaiser told me in his brightly lit living room in Winthrop, Massachusetts. Mr. Kaiser entered Dachau, outside of Munich, with the 42nd Infantry Division at the end of April 1945, and came upon hundreds of prisoners in barracks lying on shelves, four or five high, just covered with a couple pieces of straw.

“They were too weak to get up,” he said. “Some just turned their heads. Others lay there. Their eyes were the only indication they were alive. Some banged their tin cups on the side of the bunks because they were too weak to get up. The smell was so overpowering I got sick and ran out.”

He stared down at his hands that were twisting over and over each other.

“You just couldn’t believe it; you just couldn’t believe it,” he went on. “Out in the courtyard, I couldn’t move. My mind froze; the shock was complete and total. Especially when we saw the crematoria––it was still hot, with these piles of bodies, stacked five bodies high….”

His voice, which had been getting quieter and quieter, broke off. He put his head down into the cup of his palms, his shoulders shaking. Then he excused himself and left the room. I raised my hands up around my glasses to hide my tears. His words, “My mind froze…” overwhelmed my thinking.

Mr. Kaiser returned with an armful of letters. “These are from children whose classes I spoke to. I thought you might like to see them.” Schoolchildren he had told about Dachau, but not his own children. “I guess even after all this time, I can’t open up.”

He walked me to the corner where Burke and the boys were waiting in the car. When we shook hands goodbye, his eyes brimmed with sorrow. As we pulled away, I turned around and waved, and just before we turned the corner, Mr. Kaiser was still waving back.

As we headed south, toward Rhode Island, I saw Mr. Kaiser’s eyes seeing things invisible to me. Seeing more than he could bear.

When he remembered, he was back in that moment, as if it was still happening.

I learned over the next several days that, for every one of these veterans the moment of entering the camp, of walking through the gate is still happening.

“We Didn’t Know Where the Hell We Were”

It did not help that the GIs received no warning at all about what they would encounter in the camps. In my interview the next day, Nat Futterman told me, “We didn’t know where the hell we were.” He served with the 10th Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, that is not listed as an “official” liberating unit but, because he was a radio operator, an officer enlisted him for a drive to a “camp” up the road.

“We grunt soldiers didn’t know what we were doing, where we were going. It was a day-by-day thing. Certainly the officers didn’t explain anything, just: do your job, carry the radio. We didn’t know where the hell we were. When we got outside of Weimar, you could smell that something was wrong. Smell it. The thing that got me was when I looked at the leaves on the trees. I said what the hell is the matter with them? The leaves were gray. I rubbed one, and it was covered with ash. And, you know, wha, wha, what is this? And then when we walked through the gates….”

He stopped talking and spread his hands out before him, as if they could block the image.

“That’s why he doesn’t talk about it,” Mrs. Futterman looked at me. “Doesn’t talk about it.”

“It’s very hard to even think about it because it was so overwhelming when you walked through those gates…,” Mr. Futterman managed to say. “It was overpowering. We didn’t know what to do. Nobody knew what to do. Some started feeding their rations to the prisoners, and I said, ‘That’ll kill them; don’t do that.’ And then, and then …”

He paused and took a deep breath, his whole body shuddering.

“And then they came over and kissed our feet; and they, they were––it was.…” Tears began running down his cheeks; his voice cracked. “The images––this has to be hell, this cannot be this world, can’t be, ah, jeez.” His hands pushed at the air as if he might push away the images. “But then you get angry, you know, the anger was so intense.”

“Ich Bin Ein Rebe American”

Eli Heimberg opened the door before I even knocked. “The boys aren’t staying?” he asked, his voice revealing his disappointment. “I set up the den so they could watch television.”

After I assured him my husband wanted to take them to the beach, Mr. Heimberg led me into his study, which he had made into a museum of the 42nd Infantry Division. Books filled the shelves, a map detailing the division’s route through Europe hung over the couch. Photographs surrounded us of Mr. Heimberg as the 22-year-old assistant to Rabbi Bohnen, one of the 42nd Division’s chaplains. Mr. Heimberg’s first words echoed those of Mr. Futterman.

“We knew to expect horrible things when we came upon Dachau, but nothing like what we found. There was no way to prepare ourselves for it. More horrifying than the ovens were the bodies in boxcars on the track leading into the camp. One man, who must have been trying to extricate himself, was reaching out from among the bodies. He was frozen in death, as if asking, ‘Why me?’

“We went into the barracks of the Jewish inmates, most of them too weak and close to death to stand. They were lying on these wooden shelves, hundreds of them side by side. When Rabbi Bohnen told them ‘Ich bin ein rebe American’ (‘I am an American rabbi’), there came a wail as though they were letting out all their emotions they had pent up for years.”

At the memory, Mr. Heimberg broke off and tucked his chin down into his chest.

Mr. Heimberg did not want to speak about Dachau. He wanted to tell me about his work at a displaced-persons camp where he asked to be posted after the liberation. How he helped to make the survivors’ time there more comfortable and facilitated their developing self-governance. He mentioned one child, a girl to whom he had offered a candy bar. “She bit the whole thing, paper and all, and I realized she had never seen candy before.”

At the end of our conversation, I asked him if he ever had nightmares.

“No, but sometimes I have a recurring dream. I’m driving up to the DP camp in a big truck, and the entire bed is full of candy bars.”

“I Didn’t Talk About it For 40 Years”

My appointment the next day was in Maryland. When I woke up and remembered another interview awaited me, exhaustion flooded my body. What had I been thinking to plan these back to back?

“Come on, Mom, come on,” my sons said, running in the room, impatient for me to wake up. I realized how lucky I was to have them with me.

I learned from that day’s interview and many others that none of these veterans had shared with their children their experiences of witnessing a concentration camp. They had hardly spoken of it at all to anyone.

“I didn’t talk about it for 40 years,” said Dr. George Tievsky, as he showed me photographs he had taken at Dachau. They were meticulously organized and tied with a yellow ribbon. Dr. Tievsky had been a physician with the 66th Field Hospital, attached to the 42nd Division. He had served the liberated prisoners as my father had––trying desperately to keep them alive.

“Nobody knew it—just my wife, Priscilla. I couldn’t talk about it; I couldn’t talk about it because there were no words that could describe … the horror, and words would almost be sacrilegious … a disservice to those who survived.”

Another reason the veterans did not speak about their experience for decades was that when they first returned from Europe, no one wanted to hear about it.

“I don’t think anybody wanted to hear about it,” said Kay Nee, who served in the war as a USO entertainer for the troops of V Corps. “Life was tough enough without putting something more into it. And, so I … it was interesting, I kind of buckled up then, and when I went home, I discovered nobody there wanted to hear about it. Even my own mother would say, ‘Now, Kay, that’s all behind you. Forget about it, don’t even talk about it.’ And so I sort of shut up.”

Al Hirsch, who fought with the 89th Infantry Division, found not only a lack of interest in hearing but an unwillingness to believe what he had witnessed at Ohrdruf, a Buchenwald subcamp.

“People seemed so oblivious, unconcerned,” he said. “‘Oh, those concentration camps couldn’t have been that terrible.’ I heard them say more about going to a bad movie. ‘Wasn’t that picture terrible!’ I just couldn’t understand that they couldn’t understand how terrible it was.”

“My Family’s Security Was Always My Goal”

George Kaiser presented another reason for keeping silent about his role at Dachau: “We had survivors from the camps here in Winthrop [Massachusetts], so I just sort of divorced myself from it, because I figured, what have I got to add? They were the ones who went through hell.” These men and women compared their situation to that of survivors of the camps, making the veterans’ pain seem inconsequential and irrelevant.

But as I sat with Al Hirsch and his daughter Lisa in the kitchen of their suburban Baltimore home where Lisa had grown up, the deepest reason for their silence revealed itself: their desire to protect the children. “My family’s security was always my goal,” Mr. Hirsch told me, and I thought of my father, taking out a notebook whenever I visited him at the office so he could show me the list of stocks he had bought for me, “so you always have that cushion, that security.”

None of these veterans had shared their experiences as liberators with their children, even those men who had begun speaking to schoolchildren and other groups. At a commemoration of the liberation of the camps I organized for the university where I taught in Austin, Texas, Mr. Futterman said, “What I’ve said tonight is more than what I’ve ever told my wife, sitting there, in the front row, and my children, whom I love very much.”

How could they expose their family, their reason for continuing, to even the memories of the worst evil? Better to lock them away, hoping they would stay in deep storage along with the photographs almost all of them had taken with their stowed Kodak Brownie or “liberated” Leica. Better to subject only themselves to the nightmares than let the memories ruin their family’s innocent happiness.

“Oh, he buried it all those years,” the wife of Maurice Paper told me about her husband’s memories of Dachau. General Eisenhower, remembering Paper’s fluency in Yiddish and German from his having served in Africa on the general’s staff, ordered him to Dachau to serve as an interpreter for the prisoners and liberating GIs. Paper found himself not only having to convince the skeletal Jews that he himself was Jewish but to tell them that they could not leave the camp and would have to wait 48 hours before medical care, food, and clothing would arrive. His words brought terrible wails of frustration from the newly liberated prisoners.

“He never said a word,” Mrs. Paper said, “not a word, even though I knew from letters he wrote home right afterwards that it had been awful. So he wrote he had seen it, that it was unbelievable, that he couldn’t begin to describe it to me, and then I saw a few photos he had taken. But he never said a word once he was home, and I didn’t want to cause any more pain by bringing it up.”

The forward gaze of the 1950s, the need to work and get on with life, reinforced the liberators’ urge to lock away their memories of the camps.

But the images, the smells and sounds of those memories surfaced in nightmares, or when a neighborhood ballpark relined its fields with lime, or when a photograph appeared in the newspaper or on the evening news.

We the children sensed that our fathers or mothers kept some part of themselves unavailable and distant. After conveying great affection for his father, Paul Lenger, who helped liberate Ohrdruf with the 89th Infantry Division, Steven Lenger went on to say, “Even with our closeness, there was a part of him that was like a dark closet he couldn’t open up. And that came from seeing Ohrdruf,” one of the first concentration camps the GIs liberated.

“I Was Never the Same”

Nicholas Nash, whose father was among Mauthausen’s liberators, felt his father trained him and his sisters “not to ask, as asking might reawaken things…. There was always something that lay behind the eyes that you knew you’d never get to.” But the son did have some idea of what his father was hiding, because his war photos sat in an album in the den bookcase, and when at age 14 Nicholas first opened the album, he found piles of bodies, the words “Mauthausen Concentration Camp” written on the photographs’ backs.

More often than not the children of GI liberators learned where their parents had been and what they had seen there through photographs their veteran parents had taken––photographs either left sitting in albums in the den bookcase or stored away in Army trunks. But though we have learned what our parents saw, what has been more difficult to determine is how that experience affected our parents and through them, ourselves.

“I was never the same. I was never the same,” Maurice Paper said as he kept his eyes on his hands. “I couldn’t go back to school. I had every chance in the world to go back to college. I had every intention to go. I couldn’t do it.”

“Times I wondered,” Al Hirsch said, more to himself than to me, “did you ever change, did you ever change back [after Ohrdruf]?”

“I Went Into Complete Shock”

Witnessing the ghoulish scenes of death, the until-then unimaginable evil, not only changed the GIs; it imprisoned them. At first I thought repressed grief was holding them hostage to the experience. But in my very last interview––the one with Kay Nee––as I packed my tape recorder into my bag, I discovered the real prison guard.

In May 2003, nine months after my interviews of veterans in the northeast, I flew by myself to Minneapolis to interview Mrs. Nee. She and another USO entertainer had driven across Belgium and Germany in a two-and-a-half-ton truck to entertain the troops wherever they were camped. The truck was their stage as well as transportation: the side pulled down, with a piano rolling out on a pulley; one woman played while the other sang. Many times they found themselves in the thick of the action––Paris the day after its liberation, Bastogne the day the Germans broke through the Bulge, and Buchenwald a few days after it was liberated.

As she sat drinking coffee outside of Weimar one day in mid-April 1945, troops began passing by. “Hey, you want to come with us to a camp up the road?” a GI yelled.

“Sure,” she answered, thinking a camp might be a place full of hungry and homeless people needing help. At the gates, walking skeletons collapsed at her feet. A man died in her arms, his last words, “But I am dying a free man.”

“I went into complete shock,” she told me, describing the ovens with burned skeletons in them. “It was at that point that I sort of went into a shock, a protective shock, so that as I went through the rest of the camp, while I was horrified, I somehow––the reality of it was kept from me, so that I could go on.”

Even though she later took her five children to Europe to show them where she had been during the war, she did not take them to Buchenwald. She showed them Dachau but kept silent about her role at another camp’s liberation.

“It was as if the person who saw Buchenwald was somebody other than myself,” she told me, “as if I were looking at it from the outside. I tried very hard to forget the whole thing. Because I couldn’t go on thinking about it. I had to put it behind me. Be careful that it didn’t come to the front. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s a fear.”

I composed myself and tried to sound calm as I asked, “A fear of what?”

“Of the memories destroying me.”

Trauma results from an overwhelming threat of annihilation. On some deep level a traumatized person believes that recalling the moment of trauma will physically annihilate him. Unresolved trauma, then, is living terror of immediate death. One wrong turn, a slip of the thoughts, and the image of the trauma, the destroyer, will slip out of the vault, hurling one back through time into the jaw of devastation.

And while the horror behind the gates of the death camps did not threaten the lives of the GI liberators, it did destroy their sense of moral order, of humanity, of a universe directed by an ultimately divine benevolence. It annihilated the possibility of ever feeling safe again.

Mrs. Nee opened my eyes to what sat right before me all along, ever since my first interview with George Kaiser, how when he began talking about Dachau, the corpses and ovens appeared before him, his remembering took him right back into the crematorium. That was the moment he lost influence over his composure, his fear as well as his pain surfacing. “I can’t get too graphic,” he had said. He meant those words literally. He could not remain with the image. Nat Futterman could not go through the gate. Carold Bland who, with the 12th Armored Division, liberated Landsberg: “But if I try to get too graphic, it’s pretty hard to keep talking….” Edgar Edelsack who liberated Mauthausen with the 11th Armored Division: “The pictures I took were so emotionally disturbing that I gave them away. I couldn’t face looking at them.”

The Long Suffering of the GI Liberators

My father tried to lock his away in the trunk.

Even if the GI liberators succeeded in locking away the photographs, they could not lock away the fear that the memories might slip through, whether in a dream or awake, triggered by the odor of lime or by hearing the word “cordwood.” Now I knew how the veterans most reminded me of my father: a palpable distancing, signaled by the sudden speaking of themselves in the second person. “Did you ever change back?” Al Hirsch had asked of himself. In my father I had mistaken this distancing from emotion as indifference.

But it had not been indifference. He was doing all he could to lock away the terror. So he could keep my brothers and me safe.

The night after I spoke with Kay Nee, alone in the motel room, forgiveness for my father opened within me like a door opening into a new part of my heart, a place of compassion and empathy, of understanding, and release.

We need to acknowledge how the GIs who liberated the Nazi death camps have suffered terribly from what they witnessed. We need to put into the record of history that by stumbling upon the camps without any preparation, these men and women would be haunted for the rest of their lives by the images and smells of the Final Solution’s gruesome last moments. These veterans are Holocaust victims we have yet to recognize. By not doing so, we place yet another obstacle between them and peace.

Thank you.

Thank you Ms. Levinson for this extremely powerful story and for sharing with us what your father and the other veterans and USO lady experienced. Let us never forget and ensure nothing like this ever happens again.

My grandfather was also a liberator though not a US soldier. Immediately post war he worked at camps keeping them open after survivors had left to help educate the German people about what had happened. Everything these veterans say and your description of the PTSD they suffered exactly mimics my grandfathers experience. Thank You for your work interviewing these men and women. I am a therapist so I hope you’re doing ok, vicarious trauma as a result of bearing witness to their stories of so much suffering can be very tough.