by Steven Ossad

In the harbor of Tripoli, the 38-gun frigate USS Philadelphia, pride of the Mediterranean Squadron, lay at anchor. Her capture by Barbary pirates on October 31, 1803, along with her entire 316-man crew after Captain William Bainbridge ran aground on an uncharted reef, marked the most humiliating defeat of the U.S. Navy since the end of the American Revolution 20 years before. Now Tripolitanean sailors were refitting her for use against the Americans. Squadron commander Captain Edward Preble was determined to erase the stain on the infant Navy’s honor and humble the pirates, regardless of the price. He had a plan and, more importantly, he had trained the men who would carry it out.

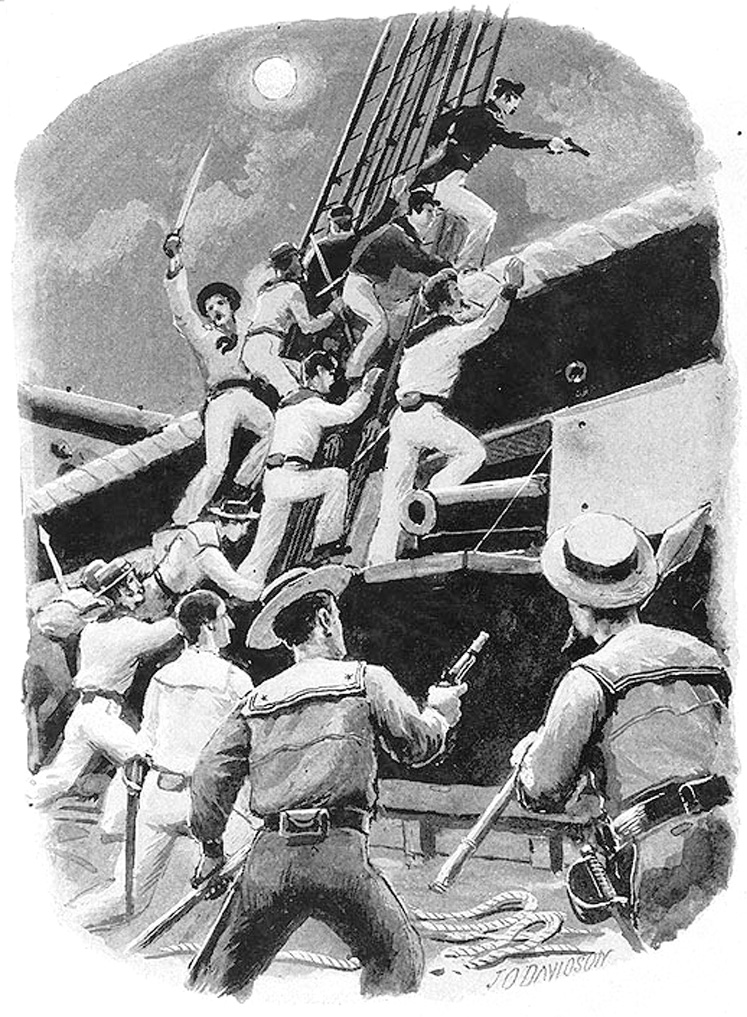

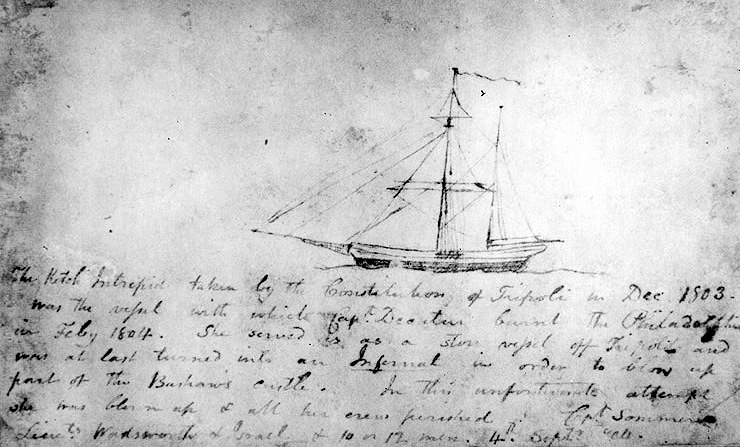

On the night of February 16, 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr., commanding the prize ketch Intrepid and a handpicked crew of 74, entered Tripoli harbor unchallenged. With the men dressed in Arab garb and masquerading as a merchantman in distress, the small boat drew up alongside Philadelphia. Sitting beside his captain, a 21-year-old midshipman clutched the hilt of his cutlass tightly and prepared himself for close combat. What Admiral Horatio Nelson later described as “the most bold and daring act of the age” was about to unfold, and Thomas Macdonough was at its center.

McDonough’s Early Career

Son of Thomas McDonough, a prominent physician and Revolutionary War hero, and Mary Vance McDonough, Thomas Jr. was born at The Trap, a hamlet in New Castle County, Del. (later renamed Macdonough in his honor). Differing sources place his birth date at either Christmas Eve or New Year’s Eve, 1783. His father had served as a militia major at the Battle of Long Island, where George Washington cited him for gallantry. After being wounded at the Battle of White Plains, Thomas Sr. returned home and began a political career, holding the office of Speaker of the Delaware Council and sitting as a justice of the Court of Common Pleas. Although virtually nothing is known of young Thomas’s early years, a letter to his sister describes a happy childhood. Orphaned at the age of 12, he inherited little property, but his parents’ wide circle of friends would prove an important influence on his naval career.

When Macdonough’s older brother James returned home after losing a foot in the February 9, 1799, engagement between the USS Constellation and French frigate Insurgente, the adventurous 16-year-old—bored by the life of a clerk— sought a commission in the Navy. By this time, the young man had changed the spelling of his family name. Through the intercession of family friend, Senator Henry Latimer, Thomas received a midshipman’s appointment directly from President John Adams in February 1800. In May 1800, still as raw and untrained as the lowliest seaman, he reported to the USS Ganges, a creaky merchantman recently converted to a 24-gun corvette. The undeclared Quasi War against France (1798-1800) was drawing to a close, but Macdonough reached the West Indies in time to participate in the capture of three vessels, including a French privateer, which he boarded after a brief skirmish. It was his first taste of action and very nearly his last.

Just after this episode, Macdonough and many other crewmen aboard the Ganges were stricken with yellow fever. Dropped off at a filthy hospital in Havana, nearly all his companions subsequently died, their bodies, as Macdonough described, “taken out in carts, as so many hogs.” Although given up for dead, he miraculously survived and eventually made his way back to his ship, but his career appeared to be over. At the conclusion of hostilities, the government reduced the size of the Navy, but family influence enabled Thomas to maintain his commission. He served for a year on the Constellation before transferring in 1803 to the Philadelphia, slated for duty against the Barbary pirates.

Macdonough and Decatur’s Adventures

In a stroke of luck, he was assigned to the prize crew of the pirate vessel Meshoba (also called Mirboka), a sloop taken off the coast of Spain, and was not on board when the Philadelphia was captured. After the prize had been delivered, Preble ordered Macdonough to the Enterprise, then under the command of Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two men.

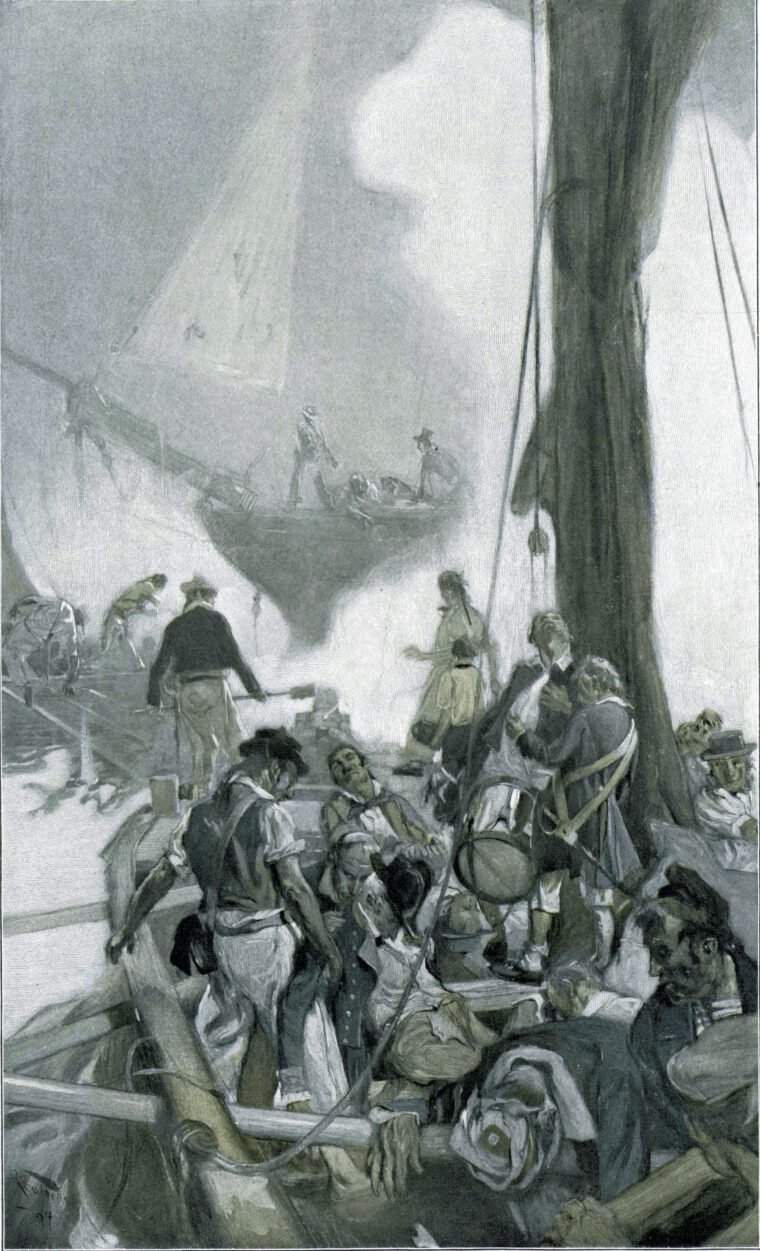

Using a small captured vessel that he re-named Intrepid and guided by Salvadore Catalano, an Arabic-speaking Sicilian pilot familiar with the port of Tripoli, Decatur and his volunteers entered Tripoli harbor after midnight. They got aboard the captured Philadelphia without alerting the enemy, and after a brief but bloody hand-to-hand struggle, killed or drove the pirates overboard and set fire to the captured ship. They returned to the Intrepid and sailed away, with only one man wounded. Their exploit gained the praise and gratitude of the nation and the respect of seamen everywhere.

On August 3, 1804, 21-year-old Macdonough again followed 25-year-old Decatur in a desperate venture. Aboard the lead vessel of a section of three American gunboats, the two men boarded a pirate ship and, after an intense struggle, forced its surrender. Taking the prize in tow, Macdonough then led a boarding party against a second boat, during which Decatur was wounded in a struggle with the enemy commander, whom he then killed in a sword fight. Macdonough fought bravely at his captain’s side, reportedly breaking his cutlass in battle and seizing a pistol from the hands of an adversary then using it to kill him. Emerging without a scratch, he was commended by Preble and praised by Decatur for his “zeal, courage and readiness.” Macdonough received a “ship-board” commission as temporary lieutenant on September 6, 1804. To the end of his life, he viewed his service during the war with the Barbary pirates as his most important assignment, describing his training and association with men like Preble, Decatur, and others as “the school where our Navy received its first lessons.”

For almost two years, Macdonough continued to serve in the Mediterranean. During one brief assignment at Ancona, Italy, he supervised the construction of four gunships, an experience that would later prove invaluable. An incident during his duty as first lieutenant aboard the 16-gun schooner USS Syren gave him a unique perspective on the growing tension between the United States and Great Britain. A party from a British warship boarded an American merchantman lying close to the Syren and tried to “impress” one of her men. Macdonough took a boat alongside the British ship and forcefully, but unsuccessfully, demanded the sailor’s return. Infuriated, Macdonough “then took hold of the man and took him in my boat and brought him on board the Syren. He was an American and of course we kept him.” After several tense minutes, the incident ended without conflict, but Macdonough never forgot the arrogance of the English officers.

In 1806, Macdonough returned to the United States and after a short furlough was ordered to Middletown, Conn., where Captain Isaac Hull was supervising construction of four gunboats. Although brief, his stay in the prosperous and growing Connecticut river town proved valuable both professionally and personally. It was an opportunity to capitalize on his naval experience in Italy, especially in the construction of small vessels. What he learned would later shape his selection and use of weapons, tactics, and maneuvers in his most crucial test. While living in Middletown, he met Lucy Ann Shaler, daughter of a well-to-do merchant, whom he subsequently married in December 1812.

For the next three years, Macdonough served on a number of ships, developing a reputation as a forceful leader and earning the respect and admiration of his men. When he took command of the gunboats stationed on Long Island Sound, he established his headquarters back in Middletown, where his relationship with Lucy and her family blossomed. It had become increasingly clear, however, that in spite of his love of the Navy, he would not be able to support Lucy as he wished if he remained in the service. Avoiding a complete separation, in 1811 he applied for a furlough—a common practice at the time—and captained the merchant brig Gulliver on a successful voyage to Europe and the East Indies. In spite of the growing tension with Great Britain, he pressed for another furlough, and when it was refused, tendered his resignation. The declaration of war against Britain on June 18, 1812, changed everything.

Macdonough Takes Command of Lake Champlain

Informing the Navy Department that he was ready to return to active service, 28-year-old Lieutenant Macdonough was ordered to take command of all naval forces on Lake Champlain in October 1812. Although it had been an important theater of operations during the Revolution, it was now a sideshow. Possibly the assignment reflected Navy Secretary Paul Hamilton’s irritation with Macdonough over the second furlough request, but regardless of his feelings, the dutiful officer set himself to the task at hand. A quick survey revealed the bleak truth. His entire “fleet” consisted of a pair of leaky gunboats and three beaten-up sloops that had been used as transports by the Army. Fortunately, the enemy was no stronger.

For the next two years, the balance of power vacillated intermittently, but remained essentially unchanged with neither side enjoying a sustained or significant advantage. The defeat of Napoleon and his exile to Elba, however, marked a turning point. With thousands of Wellington’s British veterans now freed for service in America, the strategic focus shifted to Lake Champlain, the traditional invasion route into the United States. The English began a buildup in Canada and resurrected General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne’s Saratoga strategy of 1777, preparing a new attempt to sever New England from the rest of the country. That—coupled with a southern invasion centered on New Orleans and a thrust toward New York City—would, at a minimum, put Great Britain in a favorable negotiating position as hostilities neared an end.

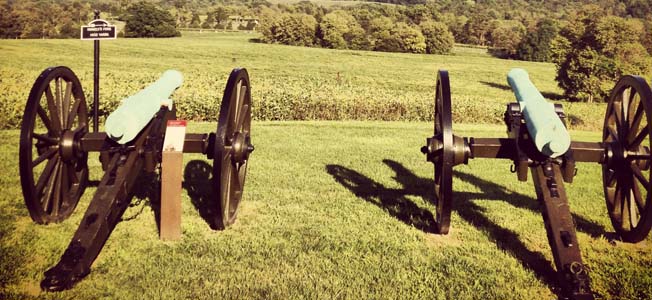

By early September 1814, the two opposing naval squadrons were nearly evenly matched in men, ships, and guns. Newly appointed Royal Navy Captain Robert Downie commanded a flotilla of 16 vessels, including his flagship Confiance (37-gun frigate), Linnet (16-gun brig), Chubb and Finch (11-gun sloops), and 12 gunboats, each armed with a long gun and a carronade (heavy, short-range cannon). Altogether his ships mounted 89 guns. Master Commandant Macdonough opposed him with 16 vessels. He had his flagship Saratoga (26-gun corvette), Eagle (20-gun brig), Ticonderoga (17-gun schooner), Preble (seven-gun sloop), and 10 gunships mounting a total of 16 cannon. Together Macdonough’s ships carried 86 guns, but held a small advantage in the number of carronades, which were effective at close quarters. Both sides had serious readiness deficiencies, but the Canadian governor-general Sir George Prevost was putting great pressure on Downie to move aggressively to support his land advance.

The English plan was simple. Prevost would move his 11,000-man army south, spearheaded by four brigades of tough regulars fresh from the victory over Napoleon. The Americans were weak; the recent transfer of most of his regulars had diminished General Alexander Macomb’s army, and his remaining 4,500 men were mostly militia. Nevertheless they were dug in on the western bank of the lake. Prevost’s plan was to rout Macomb and have Downie sweep the Americans from the lake, thus securing his supply lines. He would then take Plattsburgh, NY, and move down the Hudson River Valley toward Albany, advancing as far as he possibly could. Even if he didn’t reach the ultimate objective, his army would still hold a major bargaining chip, especially since New England’s antipathy to the war was common knowledge.

In spite of their problems, the confidence of the British was well founded. They had overwhelming superiority on the ground and all that stood between them and a great—possibly decisive—victory were a few ships led by an untested commander. Macdonough, however, also had some important advantages. First, the British fleet was bound by its overall campaign objectives and would be forced to come to battle at a place of Macdonough’s choosing. Because the enemy had to attack him, he would be able to deploy his fleet in the most favorable position to maximize his own advantages and blunt those of his adversary.

Lake Champlain Battle Plans

Realizing that an open engagement on the lake with his inexperienced crews would be folly, Macdonough decided to fight with his ships anchored close to shore. Aligned northeast to southwest in a bow-to-stern line, he took position in the confined waters between Cumberland Head and Crab Island, at the southern entrance to Plattsburgh Bay. Unable to exploit his greater maneuverability, Downie would be forced to close with the Americans, giving up his longer range gun advantage. To address his own inability to move into open water once battle was joined, and to enable him to turn while stationary and bring both port and starboard batteries to bear, Macdonough rigged the Saratoga with springs and two additional kedge anchors.

Downie’s options were limited. He would have to turn into the wind as he came around Cumberland Head and attack bow on, thus exposing the length of his ships to broadsides as they approached the enemy. His best chance would be to concentrate fire from his three heaviest ships on Saratoga and Eagle, while the remainder engaged Ticonderoga and Preble. If Prevost could capture Plattsburgh quickly, his artillery would be in position to support the fleet engagement. On paper the plan offered a reasonable chance for success.

Battle of Lake Champlain

At 9:30 on the beautiful Sunday morning of September 11, 1814, Downie’s squadron rounded Cumberland Head and entered Plattsburgh Bay. As Macdonough had hoped, the failing north wind complicated Downie’s attempt to maneuver, rendering the enemy vulnerable. As both fleets closed the range, tension mounted and silence engulfed the Saratoga. Macdonough gathered his officers around him and, kneeling together, he led them in prayer:

“Stir up Thy strength, O Lord, and come and help us, for Thou givest not always the battle to the strong, but canst save many or few.”

Minutes later, though still out of range, the Eagle opened fire. The Confiance answered with a broadside. It did little real damage, but blew up Saratoga’s hencoop, freeing the crew’s prize gamecock, which let out a defiant screech. The men cheered wildly, interpreting the cry as a clarion call of victory. Macdonough then took personal charge of the long 24-pound cannon, sighted it, and pulled the lanyard. The shot tore across the enemy flagship’s deck, killing and wounding several men. The battle was on.

Given the numbers engaged and weapons involved, the fighting became intense beyond all expectations. Julius Hubbell, a local lawyer, was watching from shore. He wrote that “the firing was terrific, fairly shaking the ground, and so rapid that it seemed to be one continuous roar, intermingled with the spiteful flashing from the mouths of guns, and dense clouds of smoke soon hung over the two fleets.” Large explosions twice hurled Macdonough to the deck, the second time leaving him stunned and leading his men to think he was dead. A cannon ball tore off the head of a gun captain and drove it against Macdonough with a force that knocked him clear across the ship.

From the start, the British were plagued by bad luck. With the winds failing, they were forced into a slugging match. Within a few minutes, Captain Downie was killed, although his loss was not communicated to the other commanders, which only added to the confusion aboard the British ships. The climax came after two hours of battering, which led one English veteran to observe that the Battle of Trafalgar was “a mere flea bite compared to this.”

With most of the Saratoga’s starboard guns out of action, and staring defeat in the face, Macdonough ordered his ship to be turned in place. The wisdom of his preparations now became evident. As the ship came around, the full weight of a fresh broadside slammed into the Confiance, now commanded by Captain Pring. Confiance tried to turn as well, but in the failing wind, could not. Within minutes she had been pounded into submission and struck her colors, effectively ending the battle after two hours of furious combat.

An American Victory

In his dispatch to Navy Secretary Jones, the laconic Macdonough wrote later that day, “The Almighty has been pleased to Grant us a signal victory on Lake Champlain.” The major ships of the enemy fleet were either captured or sunk. At the end of the battle, Macdonough reported that his ships “had not a mast that could carry a sail.” American losses exceeded 100 men killed or wounded and the British lost at least half again as many. Macdonough was magnanimous in victory; when the defeated British officers offered their swords, he said, “Gentlemen, your gallant conduct makes you worthy to wear your weapons. Return them to their scabbards.” The British appreciated the gallantry of the victor and in his report on their defeat, Captain Pring praised Macdonough for his chivalry, especially his treatment of the wounded prisoners.

Macdonough was hailed as one of nation’s greatest naval heroes, a judgment that has stood for two centuries. His tactical preparations for battle had been flawless and his achievements in surmounting the significant logistical difficulties he faced in building his fleet were extraordinary. Especially impressive was his anticipation of the enemy strategy and his well-considered deployment, which negated his adversary’s strength andmade his own weakness a virtue. Finally, his personal courage and the timing of the maneuver that brought his ship about at the crucial moment to clinch the victory, remains the stuff of legend.

The strategic achievement was, if anything, even more impressive. Many historians describe Lake Champlain as the most important and decisive battle of the war, surpassing the celebrated Battle of New Orleans, as well as the better-known ship-to-ship naval engagements. The invasion from Canada was repulsed and the British had no significant territorial gains to support their position in the final treaty negotiations. Essentially, the war ended with a return to the status quo.

In the aftermath of victory, honors and gifts were showered on Macdonough. He was promoted to captain and voted the thanks of Congress, which also authorized the striking of a gold medal. Vermont and New York awarded him large land grants. Delaware bestowed on him a sword and silver tea set, and commissioned a portrait by Thomas Sully that still hangs today in the state capital. He remained modest throughout and sought only to return to active duty. In the years after Champlain, he held various assignments before assuming command of the Constitution and the Mediterranean Squadron in 1824. Poor health, however, led to his request to be relieved the following year.

Macdonough departed for home in the merchant brig Edwin, but died at sea on November 10, 1825, and was buried at Middletown next to his wife. Their grave marker reads: “They were lovely and pleasant in their lives; in their death they were undivided.” Although he does not enjoy the renown of his friend Stephen Decatur or his other contemporaries, the Navy has not forgotten Thomas Macdonough. Four warships have carried his name and his great battle is still studied by midshipmen. At Plattsburgh, a large bronze Eagle mounted atop a 135-foot monument keeps a silent watch over Plattsburg Bay in Lake Champlain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments