By Peter Suciu

Even now, six decades after the end of World War II, the words “potato masher” just as easily conjure images of the legendary German hand grenade as they do kitchen utensils. The small antipersonnel weapon is as unique in design as any other piece of military equipment, and as such has become popular with modern-day collectors. The image of American soldiers with grenades hooked onto their equipment or German soldiers with grenades tucked in their belts is familiar to World War II buffs. During the war, these portable yet lethal weapons were produced in the millions by all sides in the conflict.

But the history of hand grenades goes back much further. Arguably the first hand-thrown explosives or incendiary bombs appeared at the height of the Byzantine Empire in the 8th century, when jars filled with the infamous “Greek fire” were thrown at enemy soldiers. A few hundred years later, saltpeter-based gunpowder was developed in China and used to construct primitive bombs. In the 15th century, such bombs made their way to Europe and over time were placed in metal shells, creating what could be described as the first true grenades. The word “grenade” in fact comes from the French “pomegranate,” and scholars suggest that this is because the early hand grenades resembled the fruits, and also because the pomegranate tends to explode as it ripens to spread seeds over a wide perimeter.

The weapon was originally one of a specialty, hence the designation “grenadiers.” The grenades of this era were bombs that were loaded with powder and contained a fuse. The grenadiers had to have the strength to throw these heavy chunks of steel great distances. The 17th-century military march, “The British Grenadier,” explains this role very precisely in a passage: “Whene’er we are commanded to storm the palisades, Our leaders march with fuses, and we with hand grenades.”

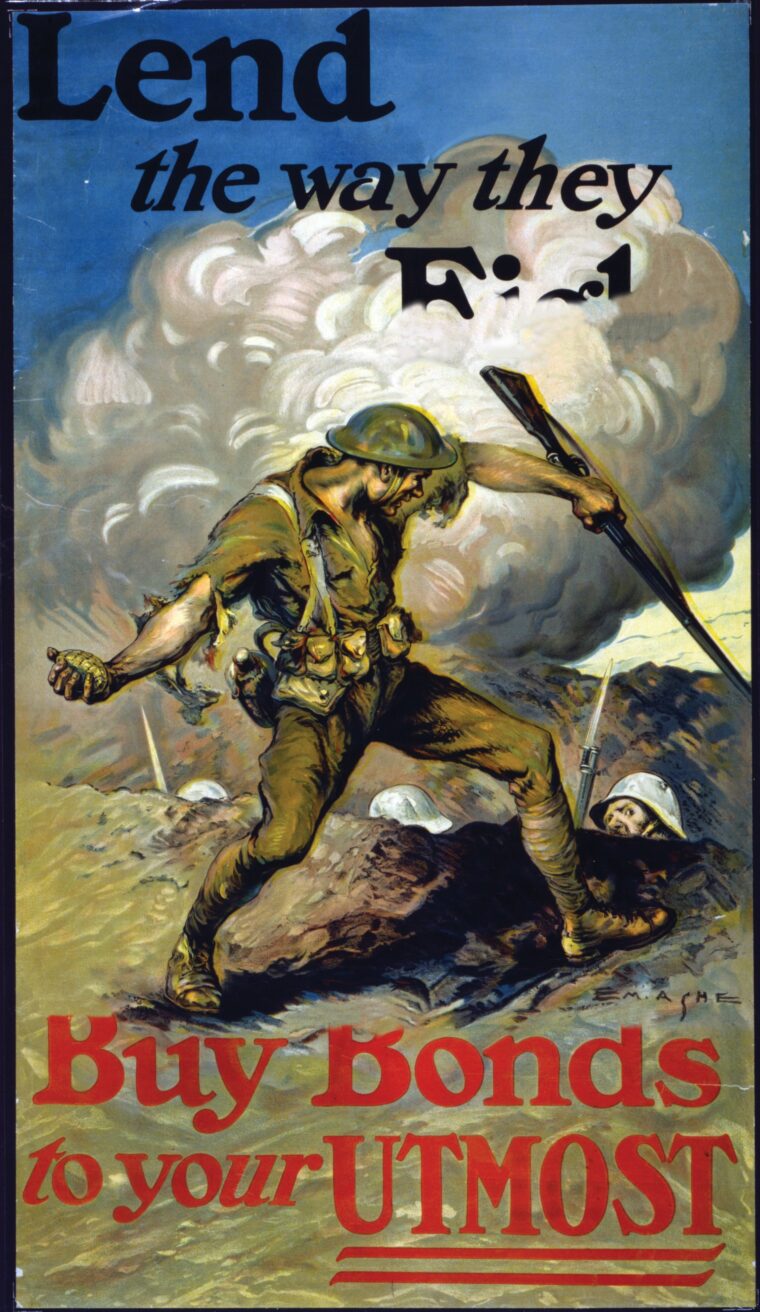

Part of the trick was determining how long to wait once the fuse was lit before throwing the bomb. Too early and there was a chance it could be thrown back; too late was far worse. The greatest threat was from enemy fire, and the early grenadiers were men who had the courage to storm enemy positions, often with the “forlorn hope,” where the causalities were typically very high. As a result, over time the grenadiers became elite troops in many European armies, and grenades were just one of many weapons they wielded. By World War I, however, grenades had become a more common infantry weapon, issued and used by virtually everyone.

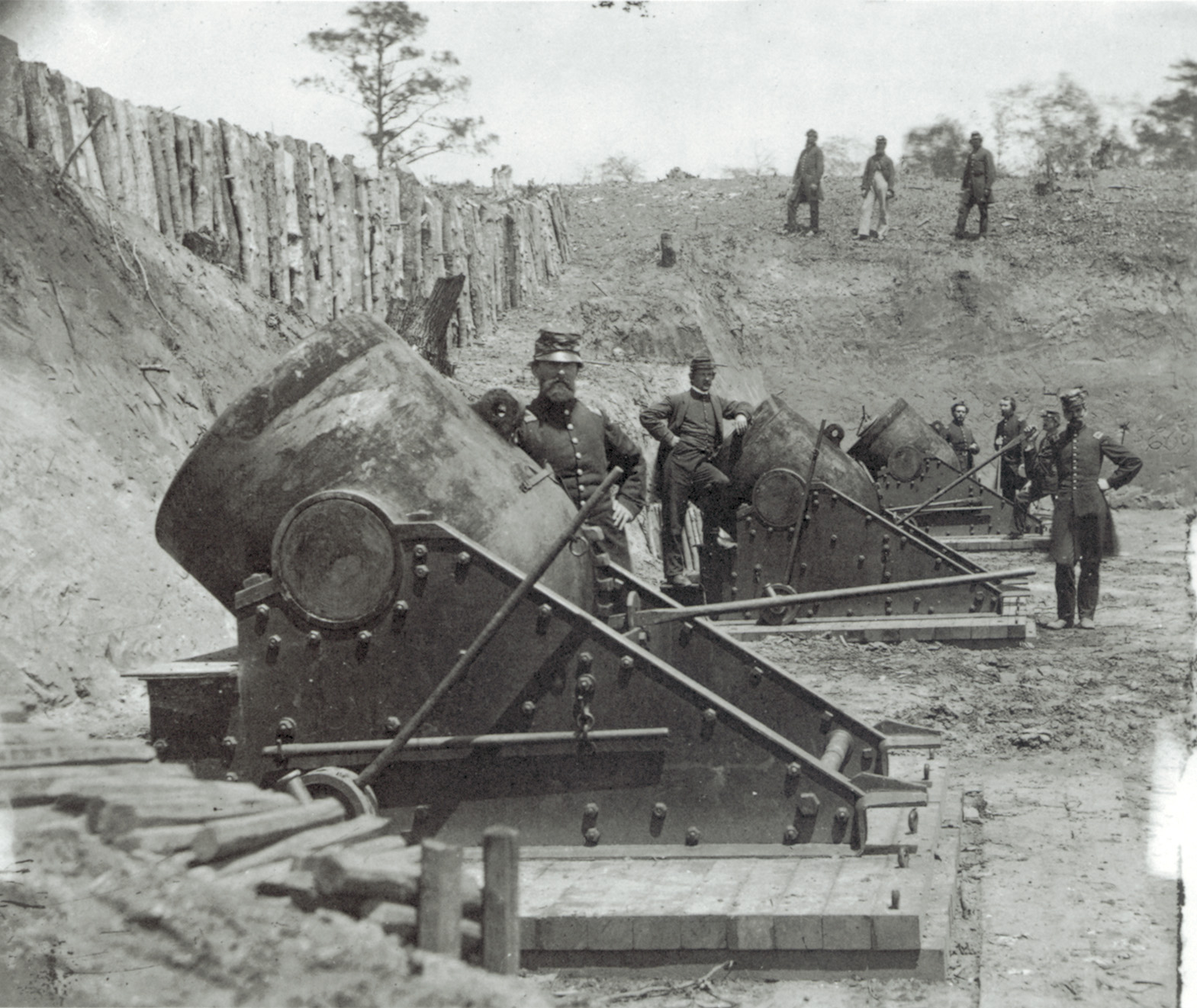

The years leading up to World War I saw the transformation of the hand grenade into the weapon we recognize today. After Germany’s opening moves deep into France in 1914, the Allies rallied, the armies dug in, and the conflict reached an impasse; each side looked at new and better ways to kill more of the enemy.

“I believe that the grenade became very useful in trench warfare; the trenches were often close enough to be able to lob a grenade into the enemies’ trench. The rifle was almost useless in trench fighting, as no one stuck their heads above the parapet—at least not more than once—and the rifle was ungainly in the narrow trenches,” says Gus Bryngelson, a longtime World War I collector and author. Bryngelson says that the grenade was also useful in clearing trenches around the next corner or past the traverse. “Most hand grenades at the beginning of World War I were the same as those used for centuries. The French M1847 is a classic example, as it was just a hollow iron ball filled with explosive and a fuse, sometimes a match-lit fuse or a friction-primed fuse. This is the type of grenade we all knew growing up watching Boris Badenov in Rocky and Bullwinkle.”

It was also during World War I that the role of the traditional grenadier changed forever. Any soldier with a good arm was suddenly called up to toss grenades toward enemy trenches. “It was during World War I that the grenadiers changed into bombers,” says British hand grenade collector David Sampson, who notes that the British versions of grenades were typically called Mills bombs. The Mills bombs were developed at the Mills Munitions Factory in Birmingham, England, and were a follow-up to a pre-World War I design. This led to the first self-igniting hand grenade, which the British War Department described as a “safe grenade.”

Several grenade patterns were produced. The most common design among the Allied forces featured grooves, which gave the grenade its comparison to a pineapple. It was thought that the segmented design would aid fragmentation when it exploded and make the device more deadly. This also made the grenade easier to grip. In all, about 75,000,000 Mills bombs were produced in World War I, while the British worked to improve the early designs, finally adapting a modified version called the No. 36, which remained in service until 1972.

Americans followed the British pattern with the grooves, but considered a variety of shapes and sizes. Notably, the Germans went in another direction, introducing a canister-shaped grenade on the end of a short stick handle. This would, of course, be the infamous “potato masher” pattern, a design that was utilized by the German Army in both world wars.

For collectors, the grenades have become as iconic to the respective nation as the uniforms and helmets. “Normally one can tell what country used a grenade by the outward appearance,” says Bryngelson. “The potato masher, for example, is the epitome of the German grenade, although in WWI the Austrians and French had grenades that were very nearly the same. The classic British grenade is the Mills Number 5, and the French had the F1 with Billiant fuse, which the U.S. used as a pattern for their overengineered failure, the MK I.”

Bryngelson adds that the variation of grenades from different countries makes collecting them all the more interesting. Even the ones that are similar have added interest, simply because of the subtle differences. A couple of examples are the wire-handled Austrian Zeitzunder and Italian Carbone grenades, and the German Eier and British “testicle” grenades.

World War II saw development in new grenades, including the lesser-known American “lemon” grenade and the German Model 1939 “egg” grenade, as well as the Japanese Type 97 and its later variations. This grenade resembles a Japanese lantern and thus contrasts strongly with Western versions.

There are many different uses for grenades, including smoke grenades, flash-bangs, blank grenades, incendiary grenades, gas grenades, and antitank grenades. Typical smoke, gas, and incendiary grenades are in the shape of a cylinder or can. The confusingly named blank grenade, much like its cousin the stun grenade, is meant to sound loud, while the latter also offers a flash of light and is sometimes called a flash-bang.

The antitank grenades that were developed during World War II essentially grew out of the basic grenade. The Germans took the M23 potato masher and attached multiple heads to create a massive grenade, although it could be tossed from only a short distance, thus potentially endangering the thrower as much as the intended target. To this end, since World War I various nations have experimented with grenades that could reach a greater distance.

Related to the traditional tossed or thrown hand grenade are the rifle grenades, which were also first introduced in World War I. These were fired from a rifle and used a special round rather than a traditional bullet. This system remained in place through the end of World War II. By the Vietnam War, this evolved into a single-shot grenade launcher, although the grenades looked more like large ordnance than a hand grenade. Today, many military assault rifles feature the grenade launcher mounted below the barrel, while the United States Marine Corps has even introduced a belt-fire grenade launcher.

For purists and collectors, the early World War I and World War II grenades remain the most desirable. Much of this has to do with the character that these items possess. While designed to explode and thus be completely obliterated, grenades still featured a certain level of craftsmanship that is often missing in other wartime items. Partly, this was because the grenade was a device where corners couldn’t be cut—or else.

Former World War I battlefields were, and still are, littered with grenades. Locals deactivate and sell them as souvenirs to the many visitors to the sites. This brings up a very important point. Although vintage grenades do come up for sale and typically have long been rendered safe, live grenades still occasionally show up for sale from private collectors. It should be stressed that collectors should not try to deactivate grenades found on battlefields. Such should be reported to authorities, and live grenades should be handed over to the police for proper destruction.

That said, there are plenty of safe grenades to collect. The biggest danger is that copies have been produced for decades and are often passed off as the real deal. Likewise, the United States and Great Britain, as well as other nations, produced training versions. Such copies have created a virtual minefield for collectors, even those who have collected for years.

“Reproductions are always a problem where items have gained value,” says Bryngelson, who adds that some reproductions are now valuable as well, and that some collectors willingly accept a replica to fill a hole, provided they know it is a replica. One example is the rare Turkish Infantry No. 2 grenade, known to have been recently made in the United Kingdom. The only known original example of the fuse assembly is in the Imperial War Museum in London.

More confusing still is that reproduction parts have been added to real grenades. The most common of these are the fuse assembly, as well as pins. Likewise, many training grenades are easily painted and passed off as something they are not. New collectors are advised to buy from reputable dealers and to network with other collectors. “As with all things nowadays, where there’s a market there’s always a scammer,” says David Sampson, who adds that it is all too easy for a dealer to pass off reproduction examples and sell them as real. He says research is the key. “Join one of the many militaria forums on the Internet, look and learn and collect pictures. It will save you a lot of time and money in the long run and leave all the rare ones for me.”

For those who want to have the visual history of hand grenades, or just an interesting paperweight, the various reproductions and copies are suitable. “Replica grenades will never be true grenades, but from three feet away you wouldn’t know it,” says Alex Cranmer of International Militaria Antiques, who adds that the repro versions make great-looking conversation pieces. “The only downside to how genuine these look is just that, they have become exceedingly easy to convert to original status,” says Cranmer. “Telling a well-doctored repro from the genuine article can be tricky.”

Another solution is copies that look the part but have none of the original mass or weight of real grenades. These are good for displays, especially with uniforms where fully weighted versions would put a strain on the cloth or materials. In these cases, resin copies are the way to go. Rob Green of Field Works puts almost as much skill into these copies as the original designers did when making the real deal. “I make a mold of the original, cast a resin copy, bondo or otherwise repair the cast copy, paint and remold it,” says Green, who notes that he does not alter the original in any way, especially when it is so easy to make an exact copy and fix that. “It leaves us with a good master model to work with, and the process keeps the original piece from being damaged or destroyed.”

For new collectors, finding grenades is not really all that hard. Even today, the basic Army-Navy surplus store is likely to have a training grenade or two, and with excellent copies such as those from International Military Antiques, there are plenty of ways to get started collecting grenades.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments