By Roy Morris Jr.

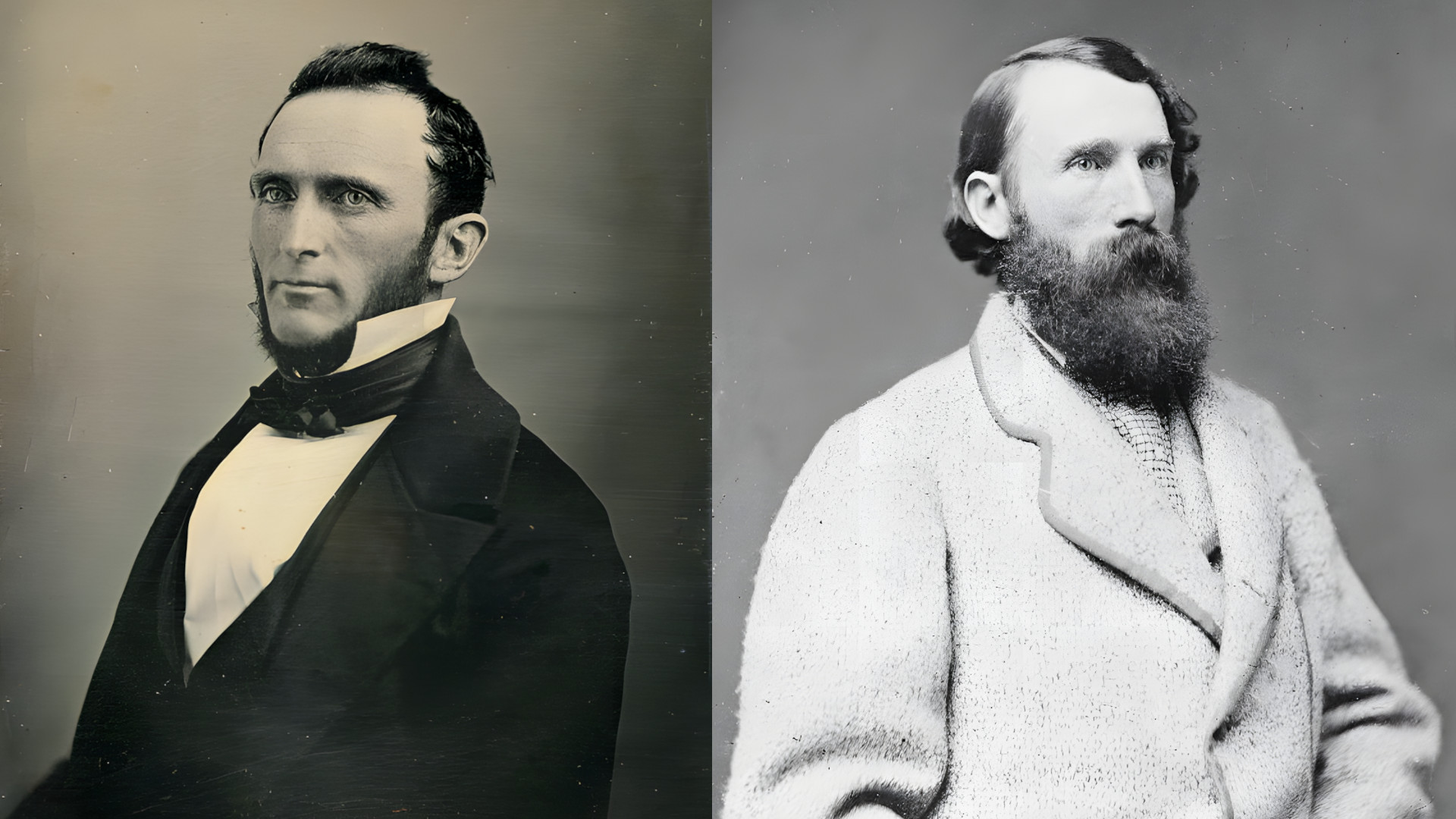

The men who wore Confederate gray were notoriously high-strung and quick to anger—none more so than Stonewall Jackson and Ambrose Powell Hill. The two touchy Virginians had attended West Point together, graduating one class apart when Hill, always bothered by ill health, had to repeat his third year. They had not been friends at the Academy, and they would not be friends in the Army of Northern Virginia, either.

Trouble began between the two eccentric generals in the summer of 1862, when an exhausted Jackson failed to support Hill’s attacks at Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill and Frayser’s Farm, during the Seven Days’ Battles. Despite the manifest ill will displayed by both men following those engagements, Robert E. Lee transferred Hill’s division to Jackson prior to the Battle of Second Manassas.

During the subsequent campaign, Jackson kept Hill in the dark about his plans, changing the order of march and neglecting to inform Hill of the changes.

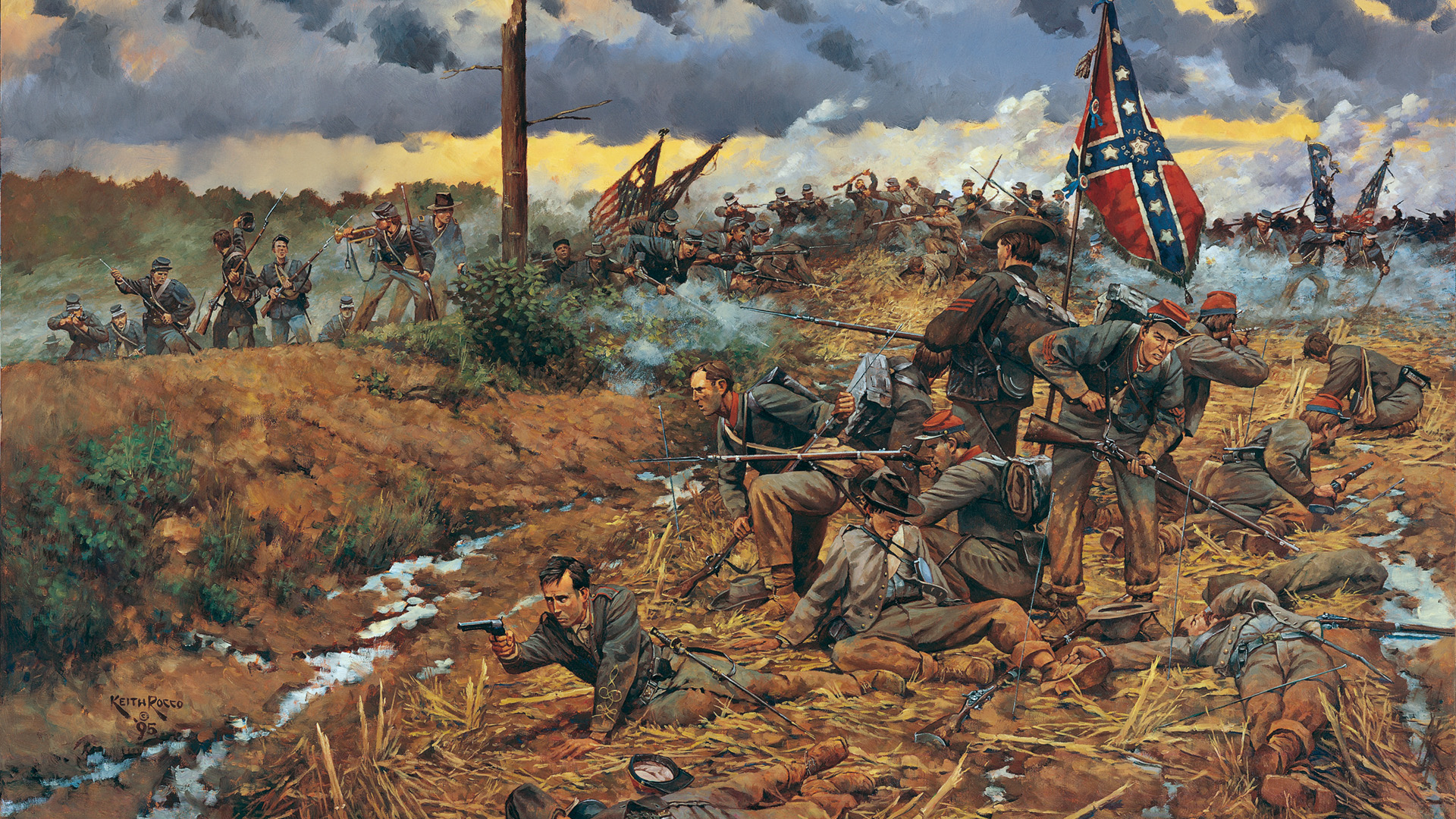

Jackson and Hill exchanged words over the latter’s supposed straggling, and Jackson asked Lee to reduce the size of Hill’s division. The next day, at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Hill had the satisfaction of saving Jackson’s bacon by arriving on the scene just in time to bolster the Confederate left and check the Union advance. Adding to Hill’s satisfaction was the knowledge that one of the broken units he had shored up was Jackson’s old Stonewall Brigade.

The ensuing victory at Second Manassas failed to heal the breach between the two men, even though Jackson paid Hill a rare official compliment when he reported that, on the part of the battlefield Hill defended, “assault after assault was made…but every advance was met most successfully and gallantly driven back.” It may have rankled Jackson to learn that Lee had told Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he considered Hill “the best soldier of his grade.”

The Feud Explodes in Front of the Troops

Jackson did not necessarily share that view, and during Lee’s ensuing invasion of Maryland he once again detailed an aide to watch Hill’s movements on the march. As Jackson’s corps headed for Harper’s Ferry to invest the Union garrison there, the smoldering animosity between the two generals erupted into the open. Perhaps driving his men at too swift a pace in order to forestall Jackson’s habitual criticism, Hill ignored the standing order for 10-minute rest stops each hour. Predictably, his men began to fall out in the late-summer heat.

When Jackson noticed the increased straggling, he personally ordered one of Hill’s brigadiers, Edward Thomas, to cease marching. Hill, riding ahead, turned back to investigate the unordered delay. “Why did you halt your command without orders?” he demanded to know. “I halted because General Jackson told me so,” Thomas said, gesturing toward Jackson, who was standing nearby.

Hill immediately rode over to Jackson, dismounted, and presented the hilt of his sword to his old West Point classmate. “If you take command of my troops in my presence, take my sword also,” Hill said. “Put up your sword and consider yourself under arrest,” Jackson said coldly, turning away.

Hill marched at the rear of his division until the corps approached Harper’s Ferry, when he implored Jackson’s aide, Lieutenant Henry Kyd Douglas, to intercede with his commander and restore Hill to duty in time for the battle. Jackson grudgingly acquiesced, and once again Hill shone on the battlefield.

But the feud between the two men never entirely went away, and when Jackson lay dying after being shot by his own men at Chancellorsville, one of his last statements was: “Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action.” Whether that was a compliment to Hill’s fighting ability, or a comment on his perceived difficulties during the march, Jackson did not say. He took his final opinion of Hill with him to the grave.

As if the Confederacy didn’t have enough problems…