By Kevin M. Hymel

The German sniper scanned the battlefield outside his bunker on the outskirts of the port city of Brest, on France’s Brittany peninsula. He had already shot an American lieutenant; now he was looking for a new target. In front of him, American soldiers occupied numerous craters, the result of Allied bombings. He spied a sergeant running from one crater to the next, talking to the men, then running back to the wounded lieutenant.

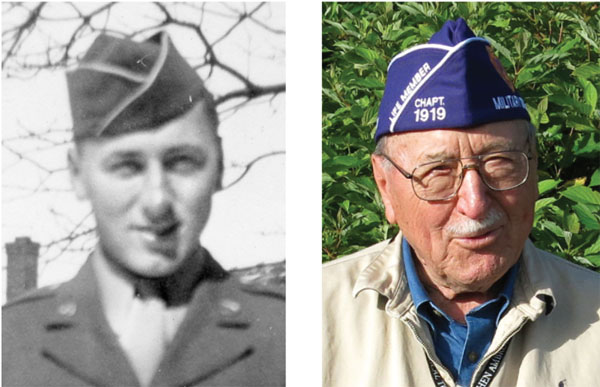

Soon the sergeant returned, again rushing to each crater. As the sergeant made yet another climb, the sniper took aim and pulled the trigger. The bullet tore into the sergeant’s lower chest, puncturing his lung and lacerating his liver. Nineteen-year-old Sergeant Mortimer Sheffloe, serial number 37567919, of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 121st Infantry Regiment, 8th Infantry Division fell back into the crater. Blood drained from his body as his life passed before his eyes. The date was September 10, 1944.

Drafted by the U.S. Army

More than a year earlier Mort Sheffloe had been a high school senior in Crookston, Minnesota, when the U.S. Army drafted him. He reported to Fort Snelling, near St. Paul, for induction with 35 other classmates in May 1943 and traveled by private rail car to Camp Fannin, in Tyler, Texas, for training. The camp had opened only two weeks before Sheffloe arrived. “It was pretty primitive,” he recalled. It had basic facilities, including a theater and a post exchange.

Sheffloe received some good news at the camp. During his induction, he had scored high enough on the Army OCT-X3 exam to qualify for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which prepared qualified candidates for engineering degrees. “I was hoping for [the University of] Southern California or the University of Texas but got Texas A&M,” said Sheffloe. So in October he started school again. Eventually, he grew weary of the academic schedule and stopped studying. He was summarily kicked out of school.

“They took me out of the dormitory and put me in the horse stables, now a barracks,” he explained.

He shipped out to Camp Polk, Louisiana, and was assigned to the 97th Infantry Division, which was completing maneuvers. A truck took Sheffloe and several other soldiers out to the field, where they gathered around a bonfire on a cold night in January 1944 as they awaited assignment to their units. Soon, the division was transferred to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, for additional training, where Sheffloe qualified as an expert on the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR).

Shipped Off to England

In early 1944, while the 97th trained to fight in the Pacific, other overseas divisions were taking heavy casualties. Instead of raising new troops for these losses, the Army stripped trained soldiers from stateside divisions to build a pool of replacements. The Army pilfered 6,000 soldiers from the 97th, including Private Sheffloe. He was made part of a “packet” consisting of five platoons commanded by five officers. They shipped out to Fort Meade, Maryland, then to Camp Shanks in New York, where Sheffloe made friends with Private Hamp L. Witt.

“He was a nice fellow,” Sheffloe recalled, “very quiet.”

Then it was a cruise across the Atlantic, ending at a replacement depot in Bristol, England. The depot occupied an old stone orphanage that dated back to the 1880s. One morning while exercising, the packet’s corporal asked the men “Did you hear? D-Day started.”

It was June 6, and the invasion of France was on. No one reacted openly to the news. “Mentally,” said Sheffloe, “we were thinking of days to come.”

Some of the men reported hearing planes flying over during the night. These could have been bombers heading to attack the German coastal defenses or Douglas C-47 Skytrain transports carrying paratroopers to drop inland, but Sheffloe heard nothing. He had slept deeply that night.

The men transferred to Yeovil in southwestern England. While Sheffloe and his packet trained, a British barrage balloon and antiaircraft unit arrived to defend the country from Hitler’s latest weapon, the V-1 buzz bomb. V-1s were winged missiles with pulse-jet engines that roared loudly until they ran out of fuel, then the engine would cut off and the rocket would impact randomly, setting off a significant charge of high explosives.

This important defense unit meant something else to Sheffloe. “We found they were all female,” he said. They were members of Britain’s Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF).

Taking advantage of a hole in the camp’s barbed wire fence one night, Sheffloe and another soldier snuck out to meet the WAAFs. With double daylight keeping the sky lit until 11:30 pm, the GIs chatted with the girls past midnight and then tried to sneak back into camp. They were caught, however, and confined to a Quonset hut brig for the night. Soon, an air raid siren roared and everyone in their tents took cover while Sheffloe and his comrade were left in the hut. Fortunately, no bombs landed nearby.

At the camp, enlisted men had to be in before dark but officers could stay out later. One night, Sheffloe stayed out too late. To prevent getting in trouble, he fashioned a lieutenant’s silver bar from chewing gum foil and placed it on his helmet liner.

“The guards saluted as I walked into camp well after dark,” he recalled.

“Bedcheck Charlie”

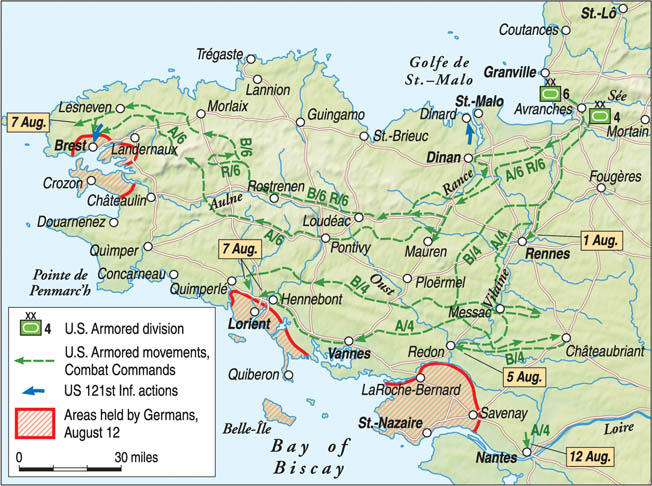

On July 10, Sheffloe and the rest of his packet boarded a British troop carrier bound for Normandy, France. In over a month of fighting, the Americans, British, and Canadians had pushed the Germans away from the beaches and, although the British were having trouble capturing the city of Caen, the Americans had cut off the Cotentin Peninsula and captured the city of Cherbourg only days before Sheffloe’s arrival. The American First Army commander, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, was planning Operation Cobra, the breakout from Normandy, with the additional forces arriving from England and with a lot help from the Army Air Forces.

Sheffloe’s ship arrived at Utah Beach around 9 am on July 11. The English Channel was packed with ships. The men went over the side into landing craft, which carried them ashore. Once ashore, Sheffloe loaded duffel bags onto a 21/2-ton truck, which he then rode off the beach. To his left stood a German bunker (today’s Utah Beach Museum). Once the truck drove through a breach in the seawall, he saw another bunker to his right (today’s Roosevelt Café). The truck drove over a causeway and through the flooded lowlands before ascending a hill to the high ground.

After a four-mile journey, the truck arrived in Ste.-Mere-Eglise, where Sheffloe and the truck’s crew awaited the rest of the packet coming on foot. Once everyone was assembled, they dug foxholes and bedded down in a hedgerow field east of the town. A few hedgerows over a temporary cemetery called Jayhawk II had been started. Sheffloe and the others, two to a foxhole, took turns sleeping or standing guard every hour. They got their first taste of the war after 11 pm and every night thereafter when a German plane flew over the American line. The German pilot earned the nickname “Bedcheck Charlie.” The American antiaircraft guns on land and at sea responded, lighting up the sky. “It was a spectacular sound and light show,” recalled Sheffloe.

Following the 121st Infantry Regiment to La Hay-du Puits

After a few days in bivouac, Sheffloe’s company commander called the men over to a truck. An officer from the 8th Infantry Division’s 121st Infantry Regiment pointed at 12 soldiers and said, “You, you, you, you, come with me.” Sheffloe was not picked, but his buddy, Private Witt, was.

Then the officer said, “I need a BAR man.” Sheffloe raised his hand and was picked. He was now part of the 121st, the Old Gray Bonnet Regiment, originally from the Georgia National Guard.

The truck delivered the replacements to a field near La Hay-du Puits, three miles north of Leese, the front line. An officer asked who his new BAR man was, but Sheffloe did not put up his hand. He was instead assigned as second scout for Lieutenant William Kapuscinski’s platoon in Company E. Private Witt was also assigned to Company E, but to a different platoon. Sheffloe liked his new lieutenant and felt the feeling was mutual.

On the first afternoon, Sheffloe learned there would be a night attack, but in a few hours it was cancelled. The next day a sergeant took Sheffloe and five other men a half mile south to a farmhouse. “You six will stay here,” he told them.

“We didn’t know it,” said Sheffloe, “but we were an outpost on the front.” The farmhouse contained a huge barrel of apple cider, which the men sipped until a nearby tank destroyer unit found out and drained the barrel into jerry cans.

One night at the outpost, Sheffloe heard a German burp gun fire at close range. He perked up his ears and put his finger on the trigger of his M1 Garand rifle.

“When that [German] gun went off I was all eyes and ears,” he recalled. Positioned behind a partially destroyed stone wall, Sheffloe opened his mouth to hear better and twisted his head to listen for twigs breaking or other noises. He heard nothing. The rest of the night was quiet.

While on this duty, Sheffloe got a break from the usual K-rations. A hefty, smiling Frenchman holding a dead rabbit approached the Americans. He cooked and served it to his liberators. Sheffloe had never before tasted this French delicacy. “It tasted like chicken,” he recalled.

Sheffloe in Operation Cobra

The next two weeks were quiet as General Bradley prepared the four corps of his First Army for Operation Cobra. Occasionally, the Germans dropped artillery shells in the 121st’s area “just to keep us on our toes,” explained Sheffloe. On July 25, some 3,000 American bombers carpet bombed the area between the French towns of Piers and St. Lô, leaving a swath of destruction for the four corps to punch through. The 8th Infantry was part of the VIII Corps, on the far west of the line.

Sheffloe was at the outpost when he saw fleets of bombers flying over. American bombers pounded the German lines and part of the American lines with bombs that fell short of their intended targets, but Sheffloe and his comrades were too far away to hear any explosions.

Three days later, on July 28, a sergeant woke the men up before sunrise and said they would be moving out in an hour. After a breakfast of K-rations in their foxholes the men moved out. “We were a jumbled mess,” recalled Sheffloe. “Everyone was moving forward at the same time.”

The Americans marched through the town of Coutances, which the 4th Armored Division had captured earlier that day. The town had not been heavily damaged, and its grand cathedral stood intact. Only some homes along the road had lost walls where tanks had smashed into their corners.

As the men departed Coutances, a German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter plane dove on some Americans about 400 feet away. Sheffloe quickly raised his rifle, unsnapped its safety, and fired as the plane pulled out of its dive. The plane disappeared as quickly as it had appeared, unharmed. “It was such a spur of the moment thing,” recalled Sheffloe. “I can still see it flying from left to right.”

He also saw his first Germans. He was about to climb a hedgerow when everyone in front of him went flat. He raced around the hedgerow corner to get a firing position and saw two enemy soldiers running away. No shots were fired. “It was just a fleeting glimpse,” he said.

A View of Mont Saint Michel

The battalion bypassed Avranches and headed south to Rennes. Along the way, Sheffloe was constantly reminded that he was in a combat zone as artillery shells intermittently flew over. The men also had to be vigilant against land mines. One morning along the march, Sheffloe and his comrades came across an American with half his leg blown off. To avoid other mines, the men had to step over and around him as a medic treated his bloody wound. But there were also wonders to be seen. South of Avranches, Sheffloe and his men glimpsed Mont Saint Michel in the distance. The church and abbey built atop a huge rock in the Mont Saint Michel Bay could be seen for miles.

“It stood out like a sore thumb,” he recalled, although he did not know what it was.

At one point, Sheffloe was climbing a hedgerow when he saw his friend, Private Witt, also climbing but going the other way. He had been wounded and was heading to the rear. The two friends spoke briefly—it was the last time Sheffloe saw him. Witt was killed on August 11 and is buried today in the St. James Cemetery in Brittany.

“We’re Going on a Combat Patrol”

Near Rennes, the regiment went into reserve. It did not last long. Later that morning, August 8, the 121st was trucked to Dinan. During the drive, the trucks paused at several stops. At one, Sheffloe and his comrades watched three French men and two French women emerge from a wooded area. In front of the Americans, one of the men pulled a pair of scissors from his pocket and proceeded to cut off one woman’s hair. She was a collaborator.

“They got a lot of courage,” Sheffloe said of the French Resistance, “from the Americans being there.”

The regiment’s new mission was to advance along the Rance River, which separated the coastal city of Dinard from St. Malo. During the first afternoon, Lieutenant Kapuscinski told Sheffloe, “We’re going on a combat patrol.”

The platoon headed through a wooded area with Private Albert K. Wodkowtiz, the lead scout, walking point. When they got to the edge of a clearing, the men could hear enemy tanks. “Give me your helmet and rifle,” Kapuscinski told Sheffloe, “and climb up that tree.” Sheffloe climbed but he could not see anything. Kapuscinski decided they had gone far enough.

As night fell, Wodkowtiz again led the way back with Sheffloe, the lieutenant, and the rest of the platoon following. Halfway back, Wodkowtiz lost the trail in the darkness, but Sheffloe stopped, realizing Wodkowtiz had made a mistake. When Kapuscinski asked what was happening, Sheffloe explained and pointed out the bent grass from their earlier journey.

“When we get back,” said Kapuscinski, “you’re going to be first scout.”

Sheffloe did not want the job, but he was in no position to argue. Instead, he led the platoon back to where it had headed out, exchanged the night’s password and countersign with the soldiers guarding the line, and found his foxhole.

Around noon the next day, Sheffloe’s unit again headed into the woods. When it reached an open field, mortars and artillery began to rain down. An order came to withdraw to a hedgerow, and the men turned and ran. “You hit the deck, fell back, got up to run, hit the deck,” Sheffloe recalled about the retreat. Private Wodkowtiz was hit on the way back and died later that day. “Somebody stayed with him but couldn’t do much.”

Sheffloe as First Scout

After that, Sheffloe became first scout, and Kapuscinski often picked him to lead night patrols. Once he offered Sheffloe and his five-man patrol pistols so they would be less conspicuous.

During a night patrol, Sheffloe and his men were in a shallow ditch next to a road when Sheffloe heard hobnailed boots crunching along the road. It was a German carrying a bucket of food. Sheffloe put his face down and heard the German whistling. He passed by without noticing the Americans. Once he was gone, Sheffloe and the others headed back to their lines.

On August 11, the platoon was near the town of Pleurtuit, working its way closer to Dinard, when the men came across a series of linked iron fences called Belgian Gates that blocked their progress. They found an opening, and Sheffloe began ordering men through. “Get moving!” he encouraged, but one man didn’t appreciate Sheffloe’s efforts. He pointed his rifle at Sheffloe and said, “Watch your back,” before squeezing through. Sheffloe speculated that the soldier, an old veteran of the Georgia National Guard, did not appreciate his young scout telling him what to do.

The company reached Dinard, but it was a ghost town. The Germans had abandoned it for St. Malo. “We just roamed around at will,” recalled Sheffloe. He stepped into a department store that was burning on one end, looked around, and left. He later watched as Martin B-26 Marauder bombers dropped their loads on one of the islands off St. Malo. “They were flying at less than 10,000 feet,” he said. “I could see the planes, not the pilots.”

The Germans in St. Malo surrendered to the 83rd Infantry Division on August 17, so the 121st was trucked back to Dinan for a rest. Sheffloe had noticed during the campaign that his 38-year-old squad sergeant was frequently missing from the unit. “I think he was suffering some sort of mental strain,” he explained. “He couldn’t handle the job.” To fill the gap, Lieutenant Kapuscinski promoted Sheffloe to sergeant.

Some Respite From the Front

While Sheffloe and his regiment were outside Dinan, a United Service Organization (USO) troupe performed songs, juggled, and told jokes from the back of a truck. As another treat, the company was trucked to a series of tents for showers.

“Take off all your clothes,” someone ordered. The naked men then filed into the showers, where they were given a bar of soap. Upon exiting they were issued new underwear and socks. They were given no towels, but by the time they made it back to their dirty shirts and pants they were dry.

“It felt good,” said Sheffloe. “It was the only shower I had.” The men returned to the bivouac area and were surprised to find an ambulance. Another company had had an arms inspection during which one man pulled out his pistol and accidentally shot the man in front of him.

Since Dinan was designated off limits to soldiers, Lieutenant Kapuscinski appointed Sheffloe and another soldier as military policemen for two nights. They patrolled the town in a jeep with a driver. Their only action came one night when a bordello madam burst into the café where Sheffloe and his partners were drinking wine with the proprietor’s family and complained that drunken soldiers were looking for her place. She wanted nothing to do with them, so the two temporary MPs confronted what turned out to be two drunk medics and told them to return to their unit.

A Fruitful Scouting Mission

While Sheffloe and his colleagues rested, the Army made plans. On August 18, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, the VIII Corps commander, tasked the 8th, 2nd, and 29th Infantry Divisions and a detachment of the 6th Armored Division to attack the port city of Brest, the westernmost port in Brittany, which the 6th Armored had surrounded 10 days earlier. Only a trickle of supplies was making it through the port of Cherbourg, and the newly liberated port of St. Malo was not ready to handle operations. The Americans needed another port. Middleton needed to open Brest. The irony of the battle for St. Maol and Brest was that the ports were too far from the front after the rapid advance to the German borders and were never used.

After three days of rest, the 121st trucked to an area 20 miles north of Brest. As the men dismounted, Lieutenant Kapuscinski told Sheffloe the lieutenant colonel wanted to see him. Sheffloe found him atop a haystack. The lieutenant colonel pointed to the distance.

“I want you to lead a patrol out there a couple thousand yards to see what you can see,” he told Sheffloe, who gathered up five men and headed toward Brest over a grassy field.

Sheffloe led his squad over a rise and spotted a young lady washing clothes in a stream. The Americans surprised her, but fortunately one man, Pfc. Michael Klein, spoke French. The young lady said that the Germans had left a day or two earlier and then led them to her house where two families were staying.

“Stupidly,” recalled Sheffloe, “all six of us went in and drank wine and accepted hugs and kisses.” When a Frenchmen asked, “Qui est le chef (Who is the leader)?” Klein replied that he was, but Sheffloe interrupted him. “I am the chef. Chef-loe!” The Frenchmen understood who was in charge. Fortified by the wine and with intelligence on the enemy, Sheffloe reported to Lieutenant Kapuscinski what he had discovered about the Germans.

The German Sniper at Fort Boughan

The Americans slowly pushed the Germans deeper into Brest. Key to the American advance was control of the skies. “All the way through we had four airplanes lazing above us,” recalled Sheffloe. “We were grateful we had them over us.”

Fighter bombers would peel out of the sky one after the other and strafe targets. The men never cheered when the planes blew up ground targets. While the 2nd Battalion log book referenced several incidents of the fighters strafing friendly lines, Sheffloe never witnessed any.

On the morning of September 10, Sheffloe’s 2nd Battalion attacked the Germans. In preparation, men laid out fluorescent panels to signal their locations to the circling fighter planes while American Sherman and British Churchill tanks, as well as tank destroyers, moved up.

“I was made aware of the British tanks supporting us,” said Sheffloe, “but I never saw them.”

Sheffloe’s squad came out of a wooded area near the Penfeld River and spotted Fort Boughan, a 20-foot-high, cross-shaped blockhouse surrounded by a moat. Deep craters from American bombing pocked the gravelly earth.

Once the men dispersed into the craters, Sheffloe heard the company commander order the platoon to move out over Lieutenant Kapuscinski’s SRC-536 radio (known as a handie-talkie, but which Sheffloe and his men referred to as a walkie-talkie). Just then a shot rang out. A sniper’s bullet tore through Kapuscinski’s bicep and cut a three-inch gash across his chest. By the time Sheffloe made his way over to Kapuscinski, the lieutenant was going into shock as a medic bandaged him. The captain then radioed for the platoon to hold its position, but 10 men had already moved out. Kapuscinski gave Sheffloe the map and told him, “Bring them back.”

The time was about noon.

“It Was Like a Baseball Bat to My Ribcage”

Sheffloe ran 50 yards from bomb crater to bomb crater and told each group to move back. Then he ran back to his lieutenant, but the men had not followed. Kapuscinski told him go back, so Sheffloe repeated his round. As he headed back to Kapuscinski the second time, Sheffloe ducked into a crater and climbed out. Just as he cleared the rim, the German bullet struck him in his lower right back. Someone yelled, “Get down!” but they were too late. Sheffloe fell into the crater.

“It was like a baseball bat to my ribcage,” Sheffloe recalled.

The bullet had entered his lower chest cavity, destroying ribs and tearing his lung and liver before exiting through the right side of his chest. He lay with his head at the bottom of the crater and his feet elevated. As he breathed, he could hear a sucking sound as air and blood were drawn into his lung. Sheffloe’s mind began an instant replay of his entire life. Soon his respiration rate increased and his breathing became short. No one came to his immediate aid. Fearful of the sniper, the men stayed in their craters. Sheffloe was alone.

After a little while, an aid man jumped into Sheffloe’s crater, showering him with rocks and gravel. The medic cut off Sheffloe’s field jacket and shirt, sprinkled sulfa powder over the wound, and applied a compress. He prepared a shot of morphine but stopped.

“I can’t give you morphine,” he explained. “It slows down your respiration.”

Instead, the medic unscrewed a canteen, removed a folded spoon out of its cap, poured water into it, and placed it on Sheffloe’s lips. The medic then put a raincoat over Sheffloe and placed his helmet over his face.

Arriving at an Aid Station

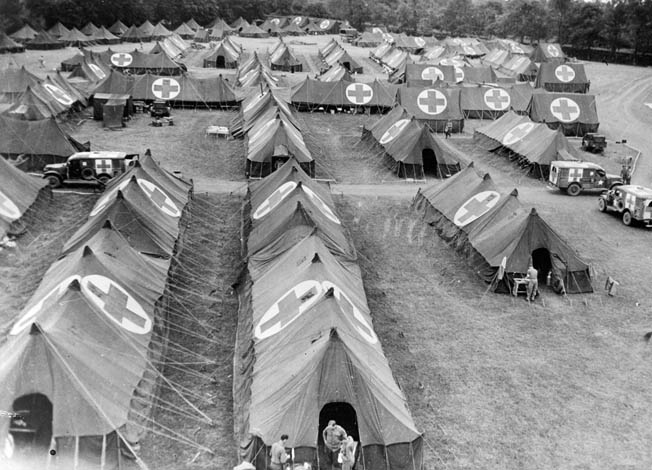

The medic and Sheffloe remained in the crater for almost four hours. Sometime after 4 pm, two medics, one holding a litter and the other a Red Cross flag, descended into the crater. They got Sheffloe onto the litter and somehow hauled him up the steep slope. They carried him a quarter mile to a waiting jeep for a rough ride back to an aid station.

The jeep arrived at a house used as the battalion aid station, and the medics carried Sheffloe’s stretcher into the basement. They were bringing him down the stairs feet first when the blood that collected in his chest cavity suddenly poured out of the litter, showering the steps in red liquid.

Downstairs, a medic filling out tags asked, “Are you spitting out tobacco juice?” The little bit of levity made Sheffloe smile. “He was trying to make me feel like everything would be okay,” explained Sheffloe. It worked. A doctor gave Sheffloe plasma and put a Vaseline gauze bandage on the wound.

His injury addressed, Sheffloe was put in an ambulance headed to a regimental collecting point. He was then transported to the 100th Evacuation Hospital. When he arrived after dark, a nurse told him that Lieutenant Kapuscinski had been asking about him. That meant a lot to Sheffloe.

“I’m proud to say I was his favorite,” Sheffloe explained, “because he selected me for the good and the bad. When he drew patrols I got them because he could rely on me.”

Later that night, Sheffloe was taken to a surgery tent, where doctors removed debris from his wounds. They also performed a phrenic nerve crush on the right side of his throat that paralyzed his diaphragm, diminishing the respiratory movements of his injured lung. They finished by replacing his Vaseline gauze bandage.

Recovery in England

Medical protocol dictated that soldiers with chest wounds could not be transported by air for seven days. Once Sheffloe passed that mark on September 17, he was loaded onto a C-47 and flown back to England. Upon arrival at the 121st U.S. Army General Hospital, he was wheeled into surgery and woke up in a private room. A nurse cared for him as he went in and out of consciousness. When he awoke, he would ask for water, and she would give him a piece of water soaked gauze to suck on.

Eventually, Sheffloe improved enough to be placed in a special ward for chest wounds. It was there that he realized the private room was for patients who were not expected to survive. “The only time I saw that room used was when a guy died in it,” he said.

At the end of September, Sheffloe was transferred to the 140th General Hospital in southern England, where he would remain for the rest of the war, going in and out of surgery.

“The first month I didn’t do much but try to live,” he explained.

Doctors eventually put a patch over the hole in his lung. He developed an empyema, an infectious pocket of pus between his lung and chest cavity. Doctors had to insert a tube into his chest to drain the fluid. It took six months to heal. At Christmastime, he was running a fever when a small British band came through the ward. Although he was a Protestant, he requested the Catholic hymn “Ave Maria.” The band’s violinist played the song and moved on.

Sheffloe saw a lot of people wheeled in and out of the ward. Most had suffered artillery or mortar wounds. He made friends with Private Harry Kornfeld, previously a jeweler from Brooklyn, who spent months in the ward. He also became friends with a 5th Infantry Division soldier named Private E.G. Simpkins from Kansas City, Missouri who had been shot by one of his own soldiers at night when he returned from a patrol at St. Nazaire. Simpkins and the man who fired the shot had been new to combat. It reminded Sheffloe why he always departed and returned to the same spot when on patrol. “I always did that,” he said.

Sheffloe spent most of his time in bed, recovering from surgeries and reading books. Once he became ambulatory, he could put on slippers and walk himself to the bathroom. He rarely went outside. One day in March, a nurse and a ward sergeant took him outside to walk in the snow.

Returning Home

Sheffloe was finally scheduled to return to the United States on May 8, 1945, but peace got in the way. In Reims, France, the Germans surrendered. Sheffloe was issued his uniform and bussed to another building in the hospital complex, where some girls came out to greet him. They all went to a dance in a mess hall and stayed out until 10 pm.

When Sheffloe returned to his ward, he learned he would not be going home until May 10. That day he boarded the troopship SS Brazil along with many other wounded men and returning Eighth Air Force crewmen. He got an unpleasant shock as he boarded. The soldier who had threatened to shoot him back near Dinard walked up to him and said, “I heard you got shot in the ass.” Sheffloe never saw him again.

After the journey across the Atlantic Ocean, Sheffloe’s first stop was Halloran General Hospital on Staten Island, New York, then a five-day train ride to McCaw General Hospital in Walla Walla, Washington, where he received a 60-day convalescent furlough.

Sheffloe took a series of trains to his home in Crookston, Minnesota. While there he learned that the first atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. He hoped this meant the war was over and he could stay home longer, but the Japanese resisted. Soon, he boarded a train to begin the journey back to Walla Walla. When he changed trains in Spokane, Washington, on August 14, he learned that Japan had finally surrendered. He got back to the hospital six hours late, at 6 am, and turned in his uniform. No one cared that he was officially AWOL.

At the end of August 1945, Sergeant Mortimer Sheffloe, who had come close to losing his life on a foreign battlefield at the age of 19, became Mort Sheffloe, civilian and proud combat veteran—aged 20.

The sacrifices made by so many such as Mort Sheffloe are too easily forgotten by those who followed. Thank God they did what they did.

God bless that young man.

They don’t make too many like that anymore.

True…Mort was pure gold.

You are a hero. My father also fought in the battle of Brest with the 555th Field Artillery Co C.

The bravery of these soldiers is beyond comprehension.