By Christopher Miskimon

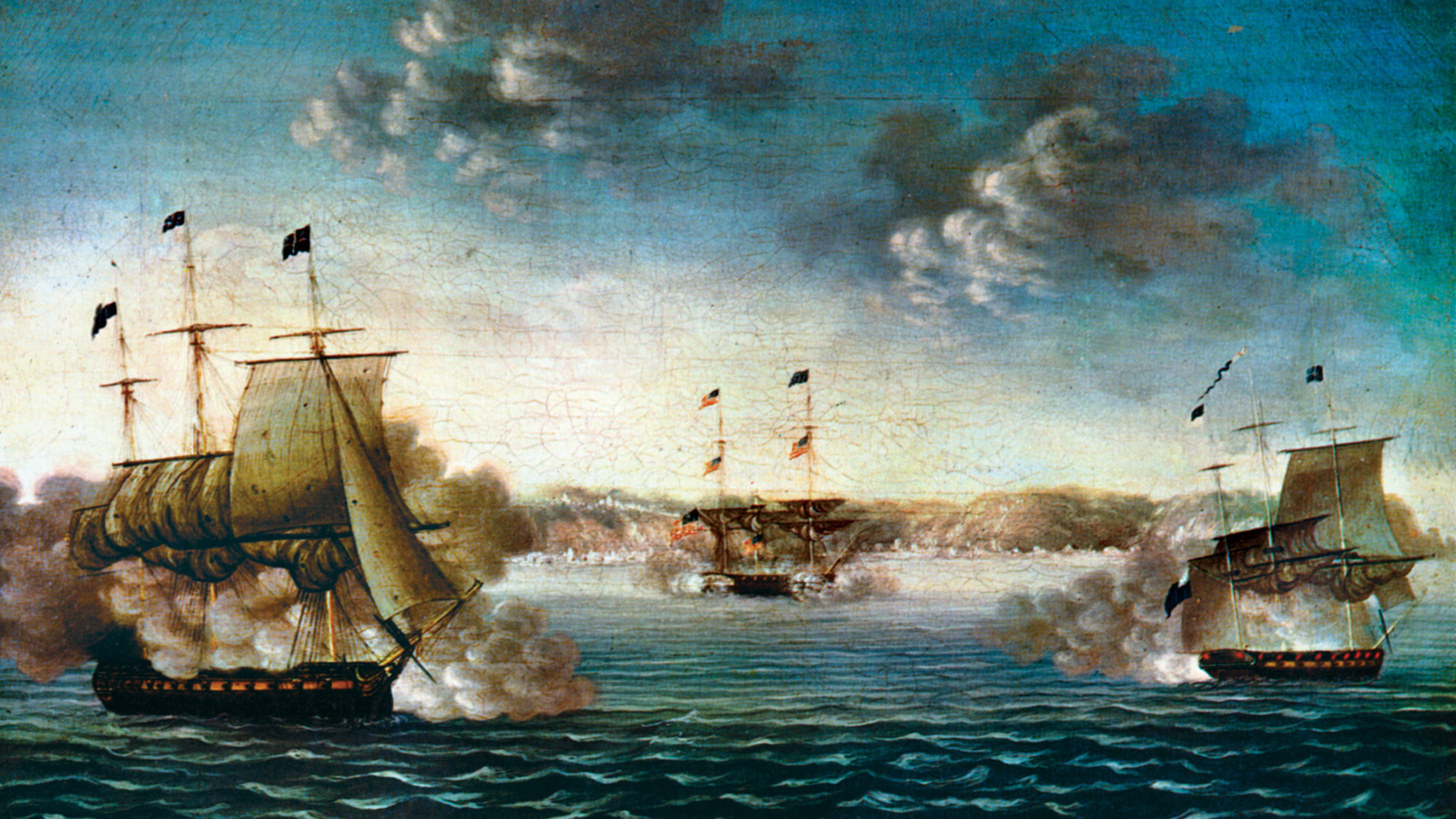

The U.S. Navy in the age of fighting sail was an institution eager to prove itself to the world. Its officers took their honor seriously and were prickly in defense of it. Although most understood the value of money, particularly the prize money from captured enemy ships, honor often mattered more. Fame and glory were their primary motivations, not uncommon among men in this era.

Stories of daring deeds and victories won were regularly carried in newspapers, providing nationwide recognition. Though tiny, the U.S. Navy was full of spirit, and the War of 1812 created the opportunity its sailors desperately wanted. Finally, they would be able to show their quality.

No officer in this fledgling service wanted to build his reputation more than David Porter. His whole life had been built around the sea and naval service. He had been at sea since the age of 16, serving on a merchantman and nearly being impressed by the Royal Navy twice. By 1798 he was a midshipman in the new U.S. Navy aboard the Constellation. During the quasi-war from 1798 to 1800 with France, he was present during the capture of the French frigate L’Insurgente. He moved up gradually and was the first officer on the Philadelphia when it was run aground during the war against the Barbary Pirates. After his release he continued in the navy and had a reputation as a courageous and capable leader.

After the War of 1812 began, Porter took command of the frigate USS Essex, a stout vessel heavily armed with carronades, powerful but short-ranged cannon. This would prove disastrous in time. Despite reservations over armament, Porter wasted little time and took Essex to sea, soon gaining a victory over the smaller British ship Alert. This was not enough to satisfy Porter’s thirst for glory; he longed to battle a frigate of equal size to his own and secure his reputation for good. His chance came when he was dispatched as part of an American squadron to the South Atlantic, where they were to harass British shipping, particularly the small warships which regularly carried fortunes in specie back to the home islands for English merchants. This was the beginning of the larger-than-life tale of courage, daring, and eventual doom told in The Shining Sea: David Porter and the Epic Voyage of the U.S.S. Essex during the War of 1812 (George C. Daughan, Basic Books, New York, 2013, 337 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover).

Quickly separated from the rest of the squadron, Porter acted on his own initiative in a way he felt carried out his orders. For a time he plied the waters of the Atlantic, seeking opportunities to sink or capture British ships. This proved difficult; the British were well established in the region, and the European powers controlling the local colonies were not always friendly. After capturing a valuable specie-carrying packet ship and relieving it of its $55,000 in coin, Porter decided to take the Essex around Cape Horn and into the Pacific Ocean. There he would target the extensive British whaling industry in place along the western side of South America and simultaneously protect American whalers in the same area. Many of the American ships in the region were unaware a war had even begun.

After a perilous voyage around Cape Horn, Essex sailed the southeastern Pacific Ocean hunting British ships. Before long numerous enemy whalers fell to the swift American frigate and its daring crew. At times, Porter had so many prizes he lacked crews to man them and often signed on captured sailors. Although Porter’s figures are likely exaggerated, the value of his captures was easily $1 to $2 million dollars. Some of them had to be laid up in the Chilean port of Valparaiso to await later transport back to the United States. The Chileans had just had a revolution of their own, and many showed great favor to Porter and his men. With the British whaling industry in shambles, Porter realized the time had come to refit his ship and rest his crew. Also, his efforts had been noticed in Britain, and the Royal Navy was sending ships to hunt him down. It was time to leave for a while.

The destination Porter chose was the island group known as the Marquesas. It was far enough away to make discovery by the British unlikely and would be a beautiful place to prepare Essex for further service. The fact that the Marquesas were home to island peoples renowned for lovely and sexually free women figured largely in his decision as well. So Essex’s course was set and soon brought the ship to Nuku Hiva Island. Here, Porter and crew found a good harbor for their ships, a wonderful climate, and the friendly women of which they had dreamed.

At that point, the tale becomes strange. Porter decided to annex the island to the United States and fought with the local tribes resistant to the idea. He renamed Nuku Hiva as Madison Island, built a fort, and brought the tribes under his control. Later, when it was time to return to the war, Porter had to fight his own mutinous sailors, many of whom did not want to leave the island paradise. Gaining control, he took them back to Valparaiso, where Essex found the fight Porter was looking for. The short-ranged carronades were useless against British long guns. The 36-gun frigate HMS Phoebe pounded the Essex into wreckage on March 28, 1814. Porter and the surviving crew were captured, though later released on parole to return home.

The 200th anniversary of the War of 1812 is in full swing, and many new books are appearing. This is a good choice for understanding the naval officers of the day and the lengths they were willing to go to in search of glory.

Battle of Falling Waters 1863: Custer, Pettigrew and the End of the Gettysburg Campaign (George F. Franks III, published by George F. Franks, 2013, 108 pp., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $17.99, softcover).

Battle of Falling Waters 1863: Custer, Pettigrew and the End of the Gettysburg Campaign (George F. Franks III, published by George F. Franks, 2013, 108 pp., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $17.99, softcover).

As the smoke slowly cleared from the battlefield of Gettysburg, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began its long retreat southward. Heavy rains, exhaustion, and a cautious command kept the Union Army from quickly following up its victory with a crushing counterattack. Still, slow maneuvering began as the Confederates withdrew toward Williamsport, Maryland. Screened by cavalry under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, they reached the river but could not cross because the bridge had been destroyed in a raid by enemy cavalry.

On July 11, 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee formed a defensive line to hold the Union forces at bay until a crossing could be made. Meade’s forces arrived on July 12 and fighting continued through the next day. During that time a new pontoon bridge was constructed and the Confederates began to withdraw behind a rear guard. A cavalry attack by forces under Union Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick on July 14 resulted in confused fighting and the mortal wounding of Confederate Brig. Gen. J. J. Pettigrew. Finally, the rebels fought a disciplined, organized withdrawal and crossed the pontoon bridge ahead of the Union cavalry, cutting the bridge loose as they crossed it. Further skirmishing occurred as Lee’s army went deeper into Virginia, but the Gettysburg Campaign was for all intents and purposes over.

This work fills in the details of Gettysburg’s aftermath. So much has been written on the American Civil War that it is hard to find anything fresh these days, but Franks has managed to do just that by concentrating on a small but important battle that has been largely neglected until now. Civil War buffs looking for a detailed retelling of the events that occurred after Pickett’s Charge will find this book of interest.

To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War (Vincent P. O’Hara, W. David Dickson, and Richard Worth, eds., Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 349 pp., maps, photographs, tables, notes, index, $37.95, hardcover.)

To Crown the Waves: The Great Navies of the First World War (Vincent P. O’Hara, W. David Dickson, and Richard Worth, eds., Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 349 pp., maps, photographs, tables, notes, index, $37.95, hardcover.)

Apart from Jutland, the submarine war, and a few other battles, World War I is largely thought of in terms of the trenches. In truth, there is good reason for this, but the naval operations of the conflict have their own underappreciated significance. Many of the weapons used, such as big-gun battleships, radio, torpedoes, and submarines, were all relatively new and had not been tested in large-scale warfare. A few, such as aircraft, were so new as to be effectively untested. Great Britain’s control of the seas was significantly challenged for the first time since the Napoleonic Wars. Theory was meeting reality worldwide.

This book provides in-depth study of the major navies of the war. Their respective doctrine, organization, ships, and training are all covered. The authors also reveal how each navy prepared for the challenges of surface and undersea warfare, antisubmarine and mine operations, and amphibious assault. Even such details as administration, intelligence, basing, and logistics are shown. Many works on this subject will focus on a single facet, such as the relative worth of British versus German warships. This work gives readers a general overview while still providing extensive detail. This book is an excellent reference work, and students of naval warfare will find it a fascinating addition to their bookshelf.

The Unseen War: Allied Air Power and the Takedown of Saddam Hussein (Benjamin S. Lambeth, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 435 pp., maps, photographs, notes index, $59.95, softcover).

The Unseen War: Allied Air Power and the Takedown of Saddam Hussein (Benjamin S. Lambeth, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 435 pp., maps, photographs, notes index, $59.95, softcover).

Modern airpower is an awe-inspiring thing— a force multiplier that gives ground forces vital support, freedom of maneuver, and a greatly enhanced ability to gather intelligence. Although the troops on the ground must always be well trained and prepared, an army that enjoys air supremacy has a much easier task ahead of it.

Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. dominance in the air has become a factor no opposing nation or group can afford to neglect. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Operation Iraqi Freedom, during which a coalition army many thought too small to easily accomplish its mission rolled over its foe while it fighters and helicopters ranged overhead with near impunity. These combat aircraft were mostly the same ones which had flown over the Iraqi deserts in 1991. However, these airframes had benefitted from over a decade of technological refinement; they were dropping many of the same weapons, but communications, accuracy, and the ability to coordinate had all improved drastically. Behind the combat aircraft, intelligence and reconnaissance planes, using such assests as the E8 Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System, improved targeting and surveillance; unmanned drones and satellites did the same, and all were used in a vast coordinated effort.

As wonderful as all this technology is, it was nothing without trained personnel to translate all of it into action. These people came from numerous nations, making the task of building effective teams more difficult. A new focus on joint operations and lessons from Afghanistan made this easier, however.

This is a detailed book which brings the many facets of an air campaign together into a coherent narrative. It is also necessarily technical and must use the byzantine assortment of acronyms the U.S. military relishes, so be prepared to consult the extensive list of acronyms provided. If you are willing to do so, though, you will gain a thorough understanding of the complexity of aerial warfare in the 21st Century.

How to Lose a War at Sea: Foolish Plans and Great Naval Blunders (Bill Fawcett, William Morrow, eds., New York, 2013, 349 pp., $13.99, softcover).

How to Lose a War at Sea: Foolish Plans and Great Naval Blunders (Bill Fawcett, William Morrow, eds., New York, 2013, 349 pp., $13.99, softcover).

American intelligence expert George Friedman has written that war largely consists of a series of mistakes, and whoever makes the fewest mistakes is often the winner. Blunders and miscalculations have many causes—pride, poor intelligence, and complacency, to name a few. This new book takes aim at many of history’s naval errors, showing how they played out. Some schemes ended in disaster, such as the Battle of Midway for Japan. Others succeeded despite the odds, often due to the quick action of a particular group or ship. For example, the air raid on the Italian port of Taranto by the British Fleet in 1940 had much going against success, but a few daring aircrews pulled it off. Other disasters were averted by a single person. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, a Soviet submarine captain had decided to fire a nuclear torpedo at American ships but was talked out of it by, of all people, his political commissar.

The book is not intended as a scholarly investigation of mistakes at sea. Rather, it is a new view of many well-known battles mixed with a few engagements almost unknown today, such as the naval portion of the Iran-Iraq War. This book is excellent light fare; it has enough detail to keep the reader’s interest while remaining easy to read and enjoy. It abounds with little-known facts that add to the entertainment and enjoyment of the book.

The Rocky Road to the Great War: The Evolution of Trench Warfare to 1914 (Nicholas Murray, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2013, 301 pp., maps, photographs, diagrams, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover).

The Rocky Road to the Great War: The Evolution of Trench Warfare to 1914 (Nicholas Murray, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2013, 301 pp., maps, photographs, diagrams, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover).

Many new weapons and concepts came to fruition in World War I. Some of them originated in that conflict; however, many were around for years or even decades. Much has been written on the evolution of machine guns, for example, but one of the iconic facets of the war is largely neglected: trenches and field fortifications. This new book from a professor at the U.S. Army’s Command and General Staff College seeks to redress that oversight.

The use of defensive positions goes back millennia, but at the end of the 19th century they became critical. Weapons were becoming more deadly with the advent of breech loading artillery, smokeless powder, and repeating small arms. Remaining in the open became suicidal. Hastily dug field fortifications were an absolute necessity. Over time they increased in refinement and became part of the art of defensive warfare. There were significant reasons for this.

Trenches could be made easily at relatively low cost. Troops in such positions could hold territory with fewer men, freeing soldiers for other roles such as attacks. As massive conscript armies arose in the late 1800s, trenches were excellent places to put them. In a trench they were easier to control and felt more secure. Green troops can be more easily blooded and will usually perform better in a solid defensive position. Also, despite their squalor, they keep soldiers alive. This book used five wars of the four decades before World War I to illustrate how field fortifications evolved into such a standard of future conflict.

Canister! On! Fire! Australian Tank Operations in Vietnam (Bruce Cameron, Big Sky Publishing, Newport, New South Wales, 2012, 940 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $60.00, hardcover in two-volume boxed set).

Canister! On! Fire! Australian Tank Operations in Vietnam (Bruce Cameron, Big Sky Publishing, Newport, New South Wales, 2012, 940 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $60.00, hardcover in two-volume boxed set).

This import has all the strengths of Australian military history books. It is detailed, lavishly illustrated, and tells a story little known to most readers outside Australia. Written by the commanding officer of the last Australian tank unit in Vietnam, the author brings a knowledge of events only a participant can provide. The Australian Army is a small but tightly knit family; when an Aussie soldier is shown in a photograph, the caption will generally identify him by name, often with interesting details about him or his actions and experiences. This can be refreshing for readers in America, for example, where the army is simply too big to include such detail or it has been lost over time.

The armored forces Australia brought to Vietnam included Centurion tanks and M113 personnel carriers. Vietnam is not generally thought of as a tanker’s war, although armor was widely used in many areas. When Australia committed to involvement in Vietnam, there was initial reluctance to send tanks, but this was overcome and company-sized tank units, called “troops” in Australian parlance did great service as part of the Aussie contingent. They supported infantry, protected bases, and patrolled roads much as American armor did. Along the way they were in the thick of the fighting against Viet Cong and NVA forces determined to destroy them; the tankers were so successful at their jobs their vehicles became priority targets.

This book will greatly please students of the Vietnam War or armor enthusiasts. The only downside is that as an import it will almost certainly have to be ordered online but is worth the effort.

War and Technology (Jeremy Black, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2013, 318 pp., notes, index, $35.00, hardcover).

War and Technology (Jeremy Black, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2013, 318 pp., notes, index, $35.00, hardcover).

Technology is a critical component of modern war, although going back millennia one can say the Greek hoplite’s shield and spear were technological weapons of their time. In the modern view technological superiority is seen as a force multiplier which gives the army possessing it a decisive advantage. At the same time, there often has been a backlash against technology, sometimes connected to the frightening pace in a world undergoing rapid industrial changes. Furthermore, technological improvements are occasionally trivialized by those who still see a soldier’s will and determination as the key to victory.

This book weaves a path through the hype on both sides of the argument. Brave soldiers can overcome a materially superior foe, but only to a degree; the bravest Zulu warrior had little chance against a Gatling gun. The author also presents the challenges technology brings, a vicious circle of invention, counter-invention, and increasing complexity requiring ever improving production capabilities. It is a complex issue, and the book does a good job of shedding understanding on the subject.

Short Bursts

The Liberty Incident Revealed: The Definitive Account of the 1967 Israeli Attack on the U.S. Navy Ship (A. Jay Cristol, Naval Institute Press, 2013, 292 pp., $36.95, hardcover). This is a second edition of the author’s original work on the subject, with added analysis from newly released National Security Agency intercepts.

The Liberty Incident Revealed: The Definitive Account of the 1967 Israeli Attack on the U.S. Navy Ship (A. Jay Cristol, Naval Institute Press, 2013, 292 pp., $36.95, hardcover). This is a second edition of the author’s original work on the subject, with added analysis from newly released National Security Agency intercepts.

At the Crossroads: Michilimackinac During the American Revolution (David A. Armour and Keith R. Widder, Mackinac State Parks Commission, 2012, 276 pp., hardcover). A revealing, well-illustrated look at the Revolutionary War in one remote Northwest Territory community, this book contains many details and small stories of personal experiences.

7 Leadership Lessons of the American Revolution: The Founding Fathers, Liberty and the Struggle for Independence (John Antal, Casemate, 2013, 240 pp., $29.95, hardcover). This book brings to light important lessons of the American Revolution using historical examples. Extensive appendices contain reports and writings of key leaders.

Congo: The Miserable Expeditions and Dreadful Death of Lt. Emory Taunt, USN (Andrew C. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, 2013, 272 pp., $44.95, hardcover). This is a retelling of the 1885 explorations of a naval officer sent to see what opportunities Africa held for U.S. business interests. It reveals the small but fascinating part America played in the “Great Game” for Africa.

Challenge of Battle: The Real Story of the British Army in 1914 (Adrian Gilbert, Osprey Publishing, 2014, 312 pp., $25.95, hardcover.) In this in-depth look at the tactics, organization, and leadership of British Expeditionary Forces at the beginning of World War I, the author discusses successes and failures.

Battle of Dogger Bank: The First Dreadnought Engagement, January 1915 (Tobias R. Philbin, Indiana University Press, 2014, 216 pp., $32.00, softcover). A German raid on British fishing fleets turned into World War I’s largest naval battle until the Battle of Jutland the following year.

Battle of Dogger Bank: The First Dreadnought Engagement, January 1915 (Tobias R. Philbin, Indiana University Press, 2014, 216 pp., $32.00, softcover). A German raid on British fishing fleets turned into World War I’s largest naval battle until the Battle of Jutland the following year.

Don Troiani’s American Battles: The Art of the Nation at War, 1754-1865 (Art by Don Troiani, text by various contributors, Stackpole Books, 2013, 264 pp., $34.95, softcover). This book presents a selection of the famous artist’s paintings. Each is accompanied by text from noted military historians.

Roman Conquests: Egypt and Judaea (John D. Grainger, Pen and Sword, 2013, 256 pp., $39.95, hardcover). This is an account of Rome’s operations in these distant territories. Numerous campaigns were necessary to fully subjugate them.

Blucher: Scourge of Napoleon (Michael V. Leggiere, Oklahoma University Press, 2014, 568 pp., $34.95, softcover). This is the first English-language biography of the famous Prussian general. The author covers his life, military career, and influence on Napoleon.

Counter-Thrust: From the Peninsula to the Antietam (Benjamin Franklin Cooling, University of Nebraska Press, 2013, 384 pp., $45.00, hardcover). After the Union seaborne invasion of the Southern Neck overreached during the Peninsula Campaign, the Confederate counterattack sent the Yankees reeling. This work looks at the campaign in detail

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments