By Coley Cowan

As Julius Caesar’s Roman army began its march on a late summer day in 52 BC in eastern France it discovered Gallic cavalry barring the way of its vanguard. It also found large bodies of Gallic horsemen on both flanks.

Caesar relied on German auxiliaries for his cavalry throughout the Gallic rebellion of 52 BC for they were superior horsemen to the Romans. He ordered his cavalry to divide into three groups to contest the Gallic cavalry. Cotus, the commander of the Gallic horse, had received orders from Vercingetorix, the king of the Gauls, to overtake the Roman army and capture some of its equipment to demoralize the men. He pinned his hopes on the Romans abandoning their baggage in hostile country, which would put their lives in grave danger. Cotus and his lieutenants swore an oath to their commander in chief that they would not return until they had ridden twice through Caesar’s long column. Vercingetorix, who had every confidence in his horsemen, was greatly pleased.

All three bodies of Germanic cavalry were soon engaged in hard fighting as the Gauls sought to pillage the Roman column. Whenever the Gauls charged, the Germanic cavalry withstood the shock of their charge and flung them back. After a sustained period of fighting, the Germanic cavalry on the right took advantage of the high ground to charge and rout the Gallic cavalry with which it was engaged. The other two bodies of Gallic cavalry fled as well. Vercingetorix was greatly displeased, and the Gallic cavalry as a whole was sorely demoralized. It was not the last time in the final weeks of the protracted rebellion that Caesar’s highly skilled and effective German horsemen would turn the tide of battle.

Gaul was in the throes of a massive revolt that year. The fractious tribes had united late in the previous year to defeat Caesar’s army. After many long months of campaigning, Vercingetorix established a fortified encampment at Alesia in August 52 BC where he planned to make a last stand. In the coming battle, he hoped to throw off the Roman yoke or, if that was not possible, he was prepared to submit to the Romans.

The 48-year-old Caesar was acutely aware of the high stakes of the campaign. He desperately needed a major victory over the Gauls to put himself on par with his chief rival, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, or Pompey. Caesar knew that the Gallic hordes he would confront at Alesia dwarfed his army. He had complete confidence in himself and his troops. As for Caesar, he was confident, determined, and resourceful. He believed that his army’s superior engineering, training, and discipline evened the odds substantially.

Caesar was born July 13, 100 BC into a patrician family of long standing. But by the time he was born it was no longer included in the inner circles of Roman politics. His father, who was a Roman senator, named him after himself.

Sixteen-year-old Caesar became the head of the family when his father died unexpectedly in 85 bc. Caesar’s aunt Julia married Gaius Marius, a prominent figure in the Republic, and Caesar benefitted from the patronage of his uncle by marriage. Caesar quickly achieved favorable recognition in the Populares party. His military career began on a high note. While serving on the staff of a military legate in 78 bc, Caesar was awarded a civic crown, the second highest military decoration bestowed upon a Roman citizen, for saving the life of a citizen in battle.

An incident in his early career illustrates both his fierce determination and his brutality. In 76 BC Caesar set out by boat for Rhodes, where he planned to gain skill in oratory by studying with a famous teacher living on the Aegean island. He was captured by Cilician pirates who held him for ransom. Caesar warned them that once he was free he would hunt them down and crucify them. They dismissed his threat, but he remained true to his word. When the Roman praetor in charge of Rhodes failed to administer satisfactory punishment to the pirates, Caesar took the matter into his own hands. He crucified them in the customary Roman fashion of execution.

In 72 BC Caesar was elected a military tribune, and three years later he became quaestor of Further Spain. During this time, he assisted fellow Populares party member Pompey in obtaining supreme command of Roman forces in the East where the Romans were engaged in stamping out piracy, as well as in a protracted struggle with Mithridates VI, the king of Pontus and Armenia Minor. In Pompey’s absence, Caesar was recognized as the de facto head of the Populares party. In 61 BC Caesar became proconsul of Further Spain.

Caesar was a favorite of the masses and spent lavishly to entertain them. But his flashy style did little to endear him to the more conservative elements in Roman politics. He was sympathetic to the rebellious Roman Senator Catiline, who conspired against the Roman Republic. When he advocated mercy for Catline and the conspirators, he further enraged his opponents in the Optimates party.

Caesar returned from Further Spain in 60 BC eager to become a consul. In light of the opposition to him in the senate, though, he needed strong allies. Despite the best efforts of his political enemies, Caesar won a great political victory when he formed a coalition in 60 BC with Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus.

The coalition, which comprised Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar, became known as the First Triumvirate. In forming the coalition, Caesar agreed to support the interests of both men if they helped to get him elected consul. Despite heavy opposition from the Optimates led by senator Marcus Porcius Cato, Caesar was elected consul in 59 bc.

Caesar met his end of the bargain. He pushed through the legislative agenda of his two fellow triumvirs. In return, he received a generous five-year appointment as governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Transalpine Gaul, and Illyricum.

Pompey’s conquests in the East had enabled him to celebrate three triumphs and had made him one of the Roman Republic’s greatest generals. Crassus was revered for having crushed slave leader Spartacus and his army during the Third Servile War. Caesar was jealous of their victories. He hoped that victory in Gaul would help him gain the military laurels he so desperately desired and restore his flagging fortune.

No sooner had he obtained his appointment as governor than a crisis developed. The Helvetii, who lived in what is now Switzerland, were tired of living on the harsh and barren terrain in the Alps. They sought warmer, more fertile lands. They chose for their new home the fertile region of the Saintonge, which lay 600 miles west of their existing lands.

As they began their migration, they violated the territory of the Aedui tribe of Gauls. The Aedui were allies of Rome who lived in what is now Savoy. The Aedui were a key ally in part because they contributed large numbers of auxiliary troops to the Roman army.

Caesar moved his existing forces into a blocking position while he returned to Italy to recruit additional manpower. His troops constructed a 19-mile-long rampart and a parallel trench to slow the Helvetii columns. In the meantime, Caesar raised two additional legions, Legio XI Claudia and Legio XII Fulminata, in Italy to supplement his existing four legions and returned to the battlefront.

Caesar attacked the Helvetii rear guard and then fell upon their main force. The Helvetii main force soundly repulsed his attack, though. Caesar then switched over to the defensive and awaited the enemy’s next move.

Using their superior numbers, the Helvetii launched a frontal assault to pin the Romans in place while also assailing the Roman flanks. The Roman third line of infantry split into two sections with each section changing face to counter the flank attack. In the ensuing battle, the Helvetii suffered heavy casualties trying to break the Romans. The Romans counterattacked and captured the enemy camp. The two sides then parlayed. Having lost to the Romans, the Helvetii agreed to return to their old homeland.

The victory had shown the Aedui that Caesar was a trustworthy and invaluable ally. He also came to the assistance of the Gallic tribes living along the upper Rhine River when Germanic tribes invaded their territories.

The victory had shown the Aedui that Caesar was a trustworthy and invaluable ally. He also came to the assistance of the Gallic tribes living along the upper Rhine River when Germanic tribes invaded their territories.

Another battle brewed when Ariovistus led 70,000 Germanic troops against the Romans. When the Germanic forces threatened to cut Caesar’s supply line, he took advantage of their superstitious nature to defeat them.

German seers had prophesied that their warriors should not fight before the new moon. Caesar advanced on the enemy camp before the new moon appeared, goading them to attack. In the ensuing bloody encounter, the Romans prevailed.

The Roman victory was due in part to the superb actions of Publius Licinius Crassus, who committed reserves on his own initiative at just the right time to swing the battle in the Romans’ favor. The Romans then drove the Germans back to the east bank of the Rhine. Ariovistus avoided capture, but he lost two thirds of his men. The victory ensured a long period of stability for the Gauls living on the west bank of the middle and upper Rhine.

About this time Caesar resolved to undertake a complete conquest of the Gauls. But first he planned to extend his conquests north to encircle Gaul from the east. He raised two additional legions, Legio XIII Gemina and Legio XIV Gemina, increasing the number of legions under his command to eight.

Caesar continued campaigning north in an effort to encircle the tribes of the interior of Gaul from the east. In 57 BC Caesar came to the aid of the Remi by defeating the Belgae near Bribax. He then marched farther north to engage the Nervii and the Aduatuci. The fierce Nervii ambushed the Romans at the Sabis River. The ensuing hand-to-hand fight nearly resulted in the annihilation of Caesar’s army; however, the superior discipline of the Romans and the timely arrival of reinforcements saved Caesar’s army from destruction.

While Caesar fought the Nervii, Publius Licinius Crassus led an independent command against the Veneti, who lived between the Seine and Loire estuaries. The Veneti submitted to the Romans with little bloodshed. Crassus’ westward march continued the process of encirclement. In addition, it secured the northern coast of Gaul for a Roman invasion of Briton, which Caesar had long been contemplating.

Caesar’s troops began building transport vessels and warships in 56 BC for the invasion. Although Caesar lost many of his boats to storms and rough seas in the crossing undertaken in 55 BC, he successfully secured a landing site on the east coast of modern Kent.

The following year five legions sailed from a location in modern Pas-de-Calais. Cassivellaunus, a Briton chief, led the main opposition against the Romans. Caesar marched against his lands, which lay north of the Thames River. He captured Cassivellaunus’s stronghold and defeated the Britons in battle. Afterward, Cassivellaunus waged a costly guerrilla war against the Romans. The Romans compelled the Britons to agree to pay tribute, but whether they ever did is uncertain.

By this time, the Romans were firmly entrenched in Gaul. Caesar also had increased the size of his forces to 10 legions. Initially, the Gallic tribes considered the Romans as their protectors, but they began to realize that the Romans intended to stay on a permanent basis. What is more, they grew tired of supporting the Roman army. The Romans not only requisitioned supplies from the Gauls under threat of force, but also forced the Gauls to furnish auxiliary troops against their will.

In the winter of 54-53 bc, the Gallic tribes of northeastern Gaul rose up against the Romans. Because of a shortage of corn as a result of sustained drought, Caesar ordered seven legions in northeastern Gaul to winter among the local tribes. Caesar deliberately placed all of the camps within 100 miles of each other so that they might furnish mutual support in a crisis.

The Eburones deeply resented having to share a major part of their meager harvest with the Romans. Ambiorix, the king of the Eburones, who lived between the Meuse and the Rhine Rivers, through a well-planned ruse persuaded one and a half legions to leave their winter camp near modern Liege to avoid being annhiliated. They informed the Romans camped in their midst that not only had all of the Gallic tribes risen in rebellion, but the Germanic tribes were planning a major incursion.

A dispute arose between Quintus Titurius Sabinus and Lucius Aurunculeius Cotta, the former arguing for a withdrawal to another Roman camp and the latter arguing against it. Sabinus won out. The retreat was planned without Caesar’s knowledge. The Eburones waited until the retreating Roman column had entered a defile, and then it annhiliated it.

When Caesar learned of the disaster, he vowed not to shave or cut his hair until his troops were avenged. The Nervii also rose up against the Romans. But Quintus Tullius Cicero, who commanded the troops threatened by the Nervii, showed more courage than Sabinus. He refused to leave his fortified camp.

The Nervii decided to give the Romans a bit of their own medicine. They began building a fortified ring around the Roman camp. In just three hours they had constructed a line three miles in circumference. It consisted of a 10-foot-high rampart protected by a trench 15 feet wide. As the siege progressed, they built mobile siege towers. Although many of the messengers that Cicero sent with a dispatch to Caesar describing his predicament were intercepted, one Nervian ally in the Roman camp was able to slip through undetected. Caesar assembled two understrength legions and his Germanic cavalry and marched to the relief of Cicero’s legion. When the Nervii and their allies learned that relief was on its way, they broke off the siege and marched to meet Caesar with a large army. Caesar, who reconnoitered the enemy host, decided to entrench and fight a defensive battle. Although a great battle was in the offing, a show of force by Caesar’s Germanic cavalry was enough to disperse the enemy.

Caesar proceeded to burn the lands of the rebellious Belgic tribes. Only the Eburones refused to submit. With little recourse left to him, Caesar invited the neighbors of the Eburones to plunder their lands. The ploy worked. Large bands of freebooters descended on the Eburones, killing them and carrying off their property.

As 53 BC drew to a close, Gaul appeared to be pacified. As Caesar prepared to return to Italy to keep tabs on political developments in Rome, he arranged his legions in winter camps that were more concentrated than they had been the previous winter. He placed two in the lands of the Treveri, two in the lands of the Lingones, and six in the lands of the Senones.

Caesar had good reason to be cautious. Rebellion was once again in the air, and this time it would not be the scattered uncoordinated rebellions of the previous year. The Gauls would act in concert.

Vercingetorix emerged as the leader of this movement. Older leaders initially opposed him, but he eventually overcame their resistance and was proclaimed king. The new monarch set about raising troops from the tribes of western and central Gaul. His strength lay in his organizational skills; specifically, he was able to pull together a tight-knit army.

Vercingetorix’s attack on the Romans at Cenabum (Orleans) in late 53 BC was a signal for the general uprising to begin. The Romans they massacred were mostly civilians, merchants, and traders. The capture of Cenabum gave Vercingetorix one of the largest Roman grain stockpiles in Gaul. The Arverni and Carnutes were joined by the Aulerci, Cadurci, Lemovice, Parisii, Pictones, Senones, and Turones. In some cases, he compelled reluctant tribes, such as the Bituriges, to join the rebellion. As for the Aedui, they remained staunch allies of Rome.

The Gauls now marched against Transalpine Gaul, the Roman province in southeastern France. Caesar began planning a winter campaign. His quick return to Transalpine Gaul came as an unpleasant surprise to Vercingetorix. The Roman commander rendezvoused with two legions stationed in the Lingones territory, as well as his cavalry, and headed north. He called the other legions to join him. In a short time he had united all 10 of his legions. Caesar obtained grain supplies from the loyal Aedui, and he then marched against Vercingetorix, whose army had besieged Gorgubina, a city of the Boii tribe in modern Burgundy. The Romans captured Cenabum, which compelled Vercingetorix to abandon Gorgubina.

Next, the Romans soundly defeated the Gauls in a pitched battle at Noviodunum. Caesar committed his German auxiliaries and swept the field. Noviodunum surrendered, and the Romans besieged the Biturges’ fortified oppidum of Avaricum (Bourges). Oppida were proto-towns in which some Gauls lived. Some were located on hilltops, while others were located in valleys. The hilltop oppida were sited to take advantage of the defensive nature of the surrounding terrain and therefore served as strong natural fortresses.

The Gauls were nearly always defeated in a pitched battle with the Romans. For that reason, Vercingetorix sought to avoid a pitched battle. The king of the Gauls instituted a scorched-earth policy to deny the Romans forage during the lean winter months. “We should also burn all of the towns except those which are rendered impregnable by natural and artificial defenses,” Vercingetorix told the Gallic chieftains. The Gauls began withdrawing before the Roman advance, burning towns and crops as they fell back. The Biturges torched 20 of their own towns in a single day, but they balked at destroying Avaricum, which was regarded as one of the most beautiful cities in Gaul. The Biturges begged Vercingetorix not to require them to destroy such a magnificent city, and he relented.

At the same time, the rebellious Gauls began ambushing Roman foraging parties. Vercingetorix’s new tactics paid off. Rations were short, and the Aedui, whose support was wavering, were lax in sending grain. Caesar encountered considerable difficulty keeping his army fed.

Avaricum was surrounded on three sides by marshes and was only approachable from the spur of a ridge; however, even that approach was well protected. A deep depression served as a natural moat between the spur and the city walls. Caesar ordered the construction of a massive earthen ramp to bridge the depression and serve as a platform for siege towers to be moved up against the walls. The Romans completed a ramp that was 80 feet high and 330 feet wide.

Vercingetorix’s army initially bivouacked 16 miles from Avaricum to monitor the Romans’ siege efforts. He soon became emboldened, though, and shifted his encampment to a strong position closer to the besieged city. He offered battle, but Caesar refused to take the bait. Vercingetorix managed to slip a large number of reinforcements into the town, and the garrison launched a ferocious sortie that temporarily drove the Romans back.

Caesar noticed during a rainstorm that the walls were more weakly manned than usual. Moving quickly to take advantage of the situation, the Romans stormed the city. The Roman soldiers had endured great hardship during the campaign and were in no mood to show mercy. Moreover, they wanted to avenge Cenabum. They slaughtered nearly everyone in the city. They found vast stores of grain inside Avaricum, and the ravenous troops gorged themselves on the provender.

As he continued the campaign, Caesar took pains to ensure the protection of his grain supply. At one point, he had to deal with treachery by a rebellious faction of the Aedui.

The rebel leaders sent 10,000 warriors ostensibly to guard Caesar’s supply lines, but in reality to reinforce Vercingetorix. Labienus marched against the Aedui and held them to account for their actions. He was able to reconcile the situation, and the loyal Aedui purged their tribe of the conspirators.

Caesar then turned south to attack Gergovia, the chief oppidum of the Arverni, in central Gaul with six legions. He sent Titus Labienus with four legions on a simultaneous thrust against the Senones and the Parisii. Caesar encamped before Gergovia and pondered its strong defenses. In the meantime, he issued orders for some of his troops to attack Gallic camps below the plateau on which the city was situated.

The attack was a success and the Romans captured several key positions; however, some of the Roman troops continued advancing up to the city walls. The Gauls took advantage of the confusion to launch a stunning counterattack on the lightly defended Roman camp. Caesar sent Legio X and part of Legio XIII to stabilize the situation, but not before he lost 700 legionnaires.

Shortly thereafter, Caesar decided to raise the siege and join up with Labienus. It was a wise move since splitting his army was fraught with risk. For his part, Vercingetorix benefited greatly from the Roman debacle at Gergovia. While Caesar called Labienus to him, more troops flocked to join the young warrior king. Caesar was in desperate need of a major victory if he were to suppress the rebellion.

Caesar turned east to engage the Lingones and Sequani in early August. As the Roman columns marched, Vercingetorix attacked them with his cavalry. The Germanic horsemen won a decisive victory over their Gallic counterparts, capturing the top commanders of the Gallic cavalry.

Having witnessed the destruction of much of his cavalry, Vercingetorix decided to make a stand at Alesia, an oppidum of the Mandubii, whose lands adjoined those of the Sequani to the east. The town was located on a plateau that rose 500 feet above the surrounding terrain.

Caesar followed and made plans to invest the town. Vercingetorix had 80,000 men to hold the position, but he was encumbered by a large number of noncombatants. Caesar’s 55,000-strong army comprised 40,000 Roman foot, 10,000 auxiliary foot, and 5,000 Germanic horse.

While the Romans toiled on their fortifications with pickaxes, turf cutters, and entrenching tools, Vercingetorix sent the remnants of his cavalry through the unfinished siege lines to their homes with instructions to bring all remaining troops to relieve the siege.

When the relief army arrived, it camped on a hilltop three miles southwest of Alesia.

The relief force consisted of approximately 100,000 Gauls. They were led by chieftains Commius, Viridomarus, Eporedorix, and Vercassivellaunus.

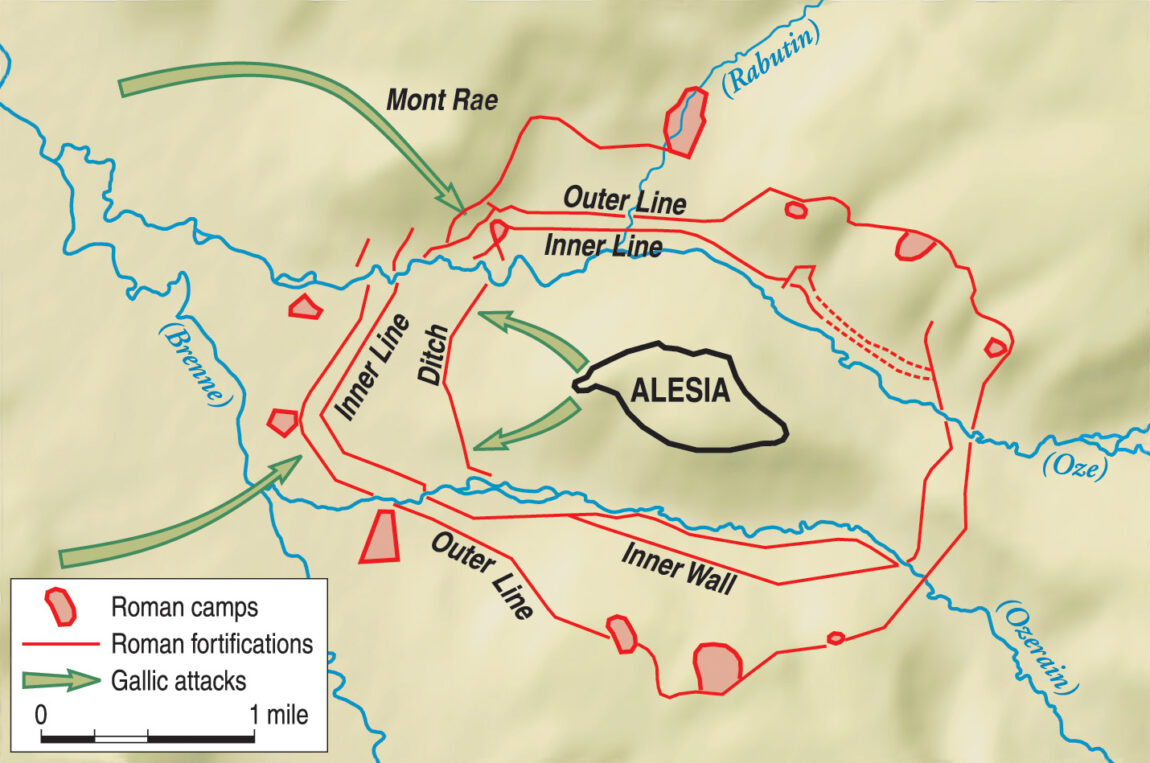

The Romans constructed an 11-mile fortified line of contravallation (inner line) and a 14-mile fortified line of circumvallation (outer line). In some areas there were substantial gaps where Caesar decided that mountainous terrain would be sufficient to deter a Gallic attack. He established seven camps between the two lines that would serve as strongpoints, as well as 23 redoubts intended to reinforce the siege lines. The construction of the inner and outer lines took one month.

The inner and outer lines consisted of a four-meter-high rampart made from excavated dirt and palisade reinforced every 33 yards with towers made of wood felled from trees in the surrounding land. The fortified line was protected by a six-yard-wide outer ditch 437 yards from the double ditch in front of the palisade. Each of those ditches was five yards wide.

The Romans constructed three types of obstacles in front of the contravallation lines to inflict casualties and, more importantly, break the momentum of the charge. Large sharpened stakes were in rows at the foot of the rampart. In front of these were round camouflaged pits arranged in a checkerboard pattern that contained smaller sharpened stakes. Farthest away from the contravallation line were rows of short logs with barbed iron spikes hammered into them. Only the very tip of the spike protruded from the ground. These defenses were designed not only to inflict casualties through grievous wounds, but also to slow the momentum of an assault by forcing the Gauls to advance slowly and cautiously.

While the Romans were busy building their siege lines, Vercingetorix decided that he had only enough grain to feed his warriors. For that reason, he ordered the women, children, and old men to leave the oppidum, but first they had to pass through the Roman lines. The Romans would not accept them nor let them depart. As a result, the noncombatants were trapped in no-man’sland without food and very little water. They soon began perishing from starvation.

The Gauls sent out their cavalry and the Romans responded. The cavalry battle ebbed back and forth before the Germanic cavalry drove off their Gallic counterparts. The relief force also made its first assault on the second night after it arrived. They bundled sticks together to create fascines to fill in the ditches and they constructed ladders of rope and wood. Beginning at midnight under cover of darkness, they launched a major attack against the west end of the Roman siegeworks. Although the fighting was bitter, the Romans repulsed the attack. Roman commander Marc Antony distinguished himself in this phase of the battle.

With winter fast approaching, the scarcity of grain and the fate of the wretched noncombatants trapped between the armies lent an air of urgency to the situation. The Gallic relief army had to break through to relieve the siege as soon as possible.

Having tested the defenses, the Gauls began planning a larger assault. They conferred with locals and carefully reconnoitered the Roman defenses. They decided that the weakest area was in the northwest corner where the Roman defenses ran along the base of Mont Rae.

The Romans had left the gap in their siege lines just west of their camp at the base of the hill.

Vercassivellaunus led 30,000 hand-picked men on a night march to the reverse slope of the hill. He instructed his men to rest through the remainder of the night and through the morning. He was to wait while a diversionary attack went forward that morning. Then, when the Romans were hard pressed, Vercassivellaunus would lead an attack with his concealed troops designed to breach the gap in the Roman defenses. The attackers would benefit from attacking downhill.

The diversion went forward as planned in the morning, and then Vercassivellaunus launched the main attack at noon. The furious assault caught the Romans by surprise. Thousands of wild-eyed Gauls streamed down the mountain toward the Romans, who were bracing for the attack. When they struck the Roman line, it bent but held. But the hard-pressed Romans at Mont Rae desperately needed reinforcements.

Caesar observed the Gauls from his command post east of Mont Rae. From that vantage point he could reinforce threatened points in his siege lines by shifting troops from one point to another.

The Gauls launched a furious assault. As they advanced, they filled in the trenches with fascine bundles, covered the spike traps, and tried to clear the Roman ramparts with a storm of arrows and javelins. When they had cleared a section of the palisade, they attempted to pull down the wall with ropes. The Romans had only a limited supply of javelins themselves and began to run low. The Gauls, with their immense numbers, replaced tired units with fresh ones as needed.

To stretch the Roman defenses, Vercingetorix led his men north across the River Oze to strike the inward-facing defenses of the Roman camp at the base of Mont Rae. He directed his men against areas of the inner siege lines that were lightly manned. Fighting for their lives, Vercingetorix’s frantic warriors toppled a wooden tower with their grappling ropes. Caesar dispatched Decimus Brutus to reinforce the inner lines; legate Caius Fabius also led reinforcements to the threatened sector. Keenly aware that defeat meant certain annihilation, the Romans fought with fury and desperation.

Although the Romans were hard pressed, Caesar ordered reserves to bolster the western defenses. During the siege he had instructed his legates to commit reserves in their sector when they saw fit rather than wasting time getting his approval.

When the Gauls began fighting their way into the camp, Caesar ordered Labienus to take six cohorts and reinforce the camp. Caesar had instructed Labienus to hold the walls as long as possible, but once it seemed they were to going to be breached, he should call together all of the soldiers manning the walls and counterattack beyond the walls. Labienus sent Caesar a message informing him that he was preparing to counterattack. Labienus also informed Caesar that he had assembled an additional 11 cohorts to participate in the counterattack.

Caesar then personally led four cohorts drawn from nearby redoubts to the Roman camp at the foot of Mont Rae to support Labienus. Just before he marched off to join the fight, Caesar issued orders for half of the Germanic cavalry to reinforce the camp at the foot of Mont Rae and the other half to attack Vercassivellaunus’s force from the left flank and rear. When Vercassivellaunus’s men, who were exhausted from hard fighting, saw the enemy cavalry assailing them from behind, they broke and fled the battle.

Clad in his purple cloak, Caesar was readily visible to his troops. His presence stimulated them to great feats. They did not even bother to throw their javelins; instead, they engaged the attackers with their swords.

Caesar’s cavalry pursued and killed or captured huge numbers of the besiegers. The Gauls lost 74 standards. The Gallic relief army abandoned their camp. Those who had survived the battle returned to their tribes.

Unfortunately for Vercingetorix, he and the trapped garrison had nowhere to go. Knowing they could not defeat the Romans alone, they fell back to the safety of the hilltop. The Gallic commander sent envoys to meet with Caesar, but the victorious Roman commander felt no need to offer any terms other than unconditional surrender.

“Vercingetorix, the supreme leader in the whole war, put on his most beautiful armor, had his horse carefully groomed, and rode out through the gates,” wrote Plutarch. “Caesar was sitting down and Vercingetorix, after riding round him in a circle, leaped down from his horse, stripped off his armor, and sat at Caesar’s feet silent and motionless until he was taken away under arrest, a prisoner reserved for the triumph.”

The captives were numerous. Each Roman soldier was given one to sell into slavery. In the aftermath of the victory, the Senate decreed 20 days of public thanksgiving.

The victory at Alesia broke the back of the Gallic rebellion. When a minor outbreak occurred the following year, the Romans crushed it in their customary manner. They reacted quickly and savagely to contain it. When the Romans captured the town of Uxellodunum on the Dordogne River in southwestern Gaul, they severed the hands of the defenders to discourage others from taking up arms against Rome.

At that point, the conquest of Gaul was complete and the Gallic tribes pacified. Upward of one million Gauls perished and another million were sold into slavery during the Gallis Wars. Nearly all of the Gauls were forcibly relocated. It was a staggering toll given that the approximate population of Gaul was 15 million.

As for Caesar, the remainder of his career is well known. While he was fixated on the conquest of Gaul, the political situation in Rome sharply deteriorated. Crassus died in 53 BC when his army campaigning in Upper Mesopotamia was destroyed by the Parthians at Carrhae. Pompey, the other surviving member of the Triumvirate, was deeply jealous of Caesar’s victory in Gaul. He orchestrated an appointment as sole counsel, and then demanded that Caesar return to Rome without his army or risk being branded as a traitor to the Roman Republic. In one of the most famous episodes of his impressive career, Caesar crossed the Rubicon on January 11, 49 bc. Pompey fled to Greece, and Caesar pursued him. On August 9, 48 bc,Caesar outfought Pompey at Pharsalus. Pompey evaded capture, but was assassinated by Roman tribune Lucius Septimius, who stabbed him to death as he attempted to land by boat in Alexandria, Egypt.

After his victory over Pompey, Caesar systematically crushed the remaining resistance in a series of battles fought throughout the Mediterranean region. Vercingetorix was imprisoned in Rome. Caesar intended to display him during his triumph that the Senate approved. However, the protracted civil war delayed the triumph for many years. Following the glorious triumph held in 46 bc, Vercingetorix was executed. It was the coda to Caesar’s illustrious and bloody Gallic Wars.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments