By Steven Weingartner

Betio is the main island of the Tarawa Atoll in the Central Pacific nation of Kiribati, formerly known as the Gilbert Islands.

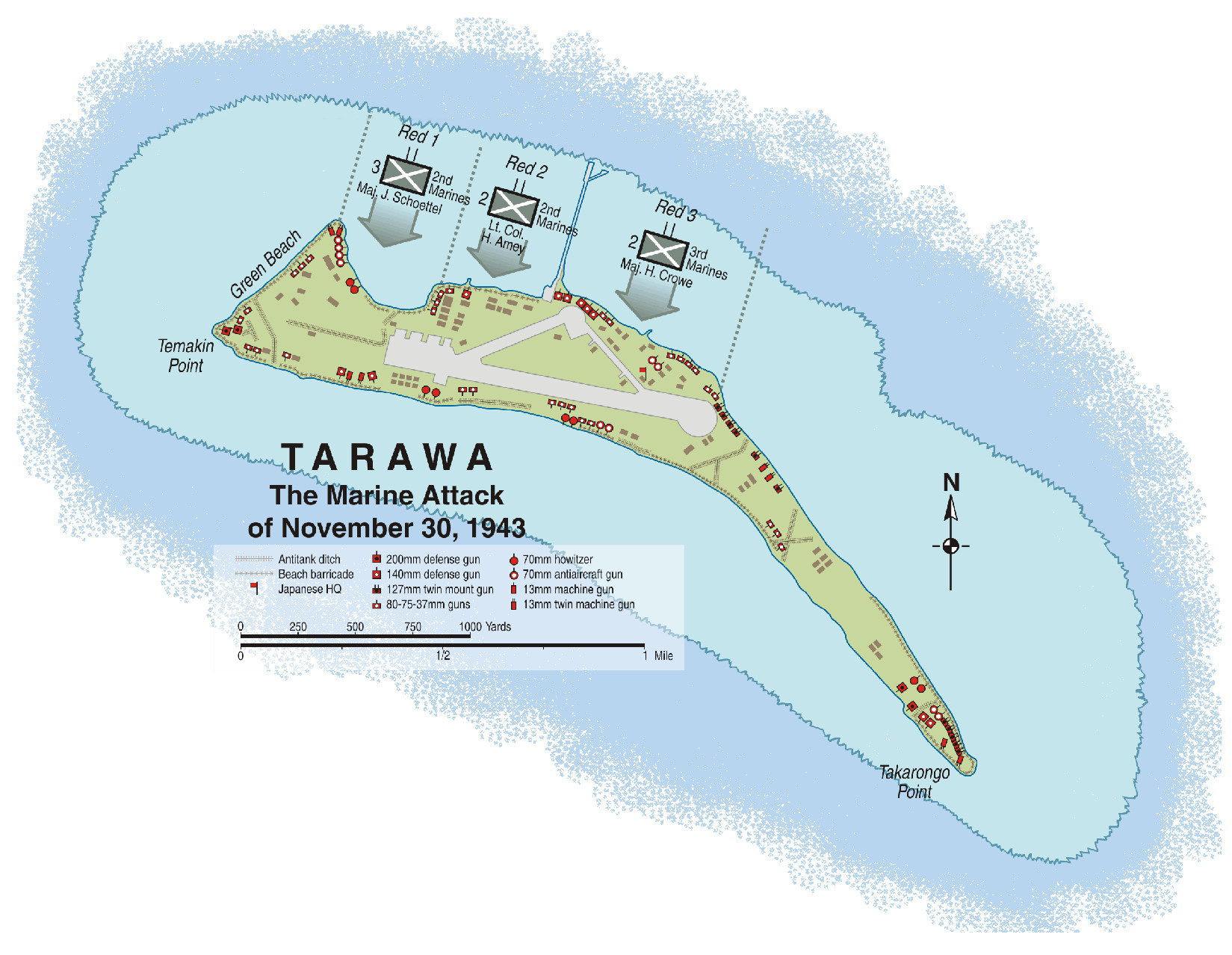

On the morning of November 20, 1943, it was also the main objective of Operation Galvanic, the American campaign to seize the Gilberts. A force of 35,000 men was set to take part in the operation.

Betio (pronounced “bay-shio”) is tiny, less than three miles long and 700 yards across, and nowhere more than ten feet above sea level. But it was strategically located in the path of the American advance, and capturing it would enable the Americans to control the region even as it provided a springboard—with, not incidentally, a completed airstrip—to continue their westward drive into the Marshall Islands and on to Japan.

In recognition of Betio’s importance, the Japanese had fortified the island and garrisoned it with some 3,000 troops plus 2,000 Japanese and Korean workers. Their strategy to contest an attack at the water’s edge was pretty much dictated by the island’s diminutive size, which precluded a defense in depth as well as tactical maneuver. So confident was he that his position was impregnable, Admiral Keiji Shibasaki, commanding the island’s garrison, boasted, “A million men cannot take Tarawa in a hundred years.”

The Americans, for their part, believed that the combination of massive firepower, primarily in the form of a pre-assault air and naval bombardment, and the fighting spirit and capabilities of the U.S. Marines of the 2nd Marine Division would enable them to quickly overcome the Japanese with acceptable, perhaps even negligible, losses.

Shortly before Operation Galvanic, in a preinvasion staff briefing at Efate in the New Hebrides Islands, a U.S. Navy admiral announced that it was not the Navy’s intention merely to neutralize the defenses on Betio: “Gentlemen,” he told the assemblage, “we will obliterate it.”

At the same briefing, a battleship captain declared, “We are going to bombard at six thousand yards. We’ve got so much armor we’re not afraid of anything the Japs can throw back at us.”

Major General Julian C. Smith, commander of the 2nd Marine Division, was incensed by what he regarded as a cavalier attitude on the part of the battleship captain. “Gentlemen,” he retorted, “remember one thing: when the Marines land and meet the enemy at bayonet point, the only armor a Marine will have is his khaki shirt.”

Following a four-hour pounding by U.S. Navy aircraft and warships, the first assault waves started toward the island at 9:00 am on November 20. Ablaze with countless fires started by the naval bombardment, and billowing black smoke, Betio seemed inert and lifeless, a literal dead zone for anyone caught in the pulverizing firestorm of high-explosive ordnance hurled against it. To the hopeful Marines in the landing craft that were then approaching the devastated shore, it appeared that the bombardment had fulfilled its purpose of destroying the defenses and killing most the Japanese who occupied them.

But these appearances were deceiving. As events would soon prove, the bombardment was astonishingly ineffective. The fortifications were mostly intact, and most of the men inside them were very much alive. Now they waited with their weapons at the ready as 2nd Marine Division amtracs churned toward them. The Marines were just minutes away from engaging in what would be one of the most savagely fought battles in World War II.

As the coxswain of LCVP #13 (Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel, popularly known as a “Higgins Boat” after its inventor, Andrew Jackson Higgins) off USS Heywood (APA-6), Boatswain’s Mate Third Class Larry Wade was involved in the battle for Betio from the very start.

Born in Wolf City, Texas, in 1924, and raised in Abilene, Texas, Larry was a high school senior when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He enlisted in the Navy on December 15, 1942, shortly after his 18th birthday. Following 12 weeks of boot camp, he attended Landing Craft School and was promoted to the rank of coxswain upon graduation.

In May 1943 he was given command of his own LCVP in the operation to retake Attu in the Aleutian Islands from the Japanese. Subsequently, he was sent to New Zealand and assigned to Heywood, one of four troopships—along with USS Sheridan (APA-51), La Salle (AP-102), and Monrovia (APA-31)—that would transport the 8th Marines of the 2nd Marine Division to Tarawa and Betio.

Larry’s LCVP was selected to be one of the control boats that would help organize and guide the LVT amphibious tractors (amtracs) to the beach in the initial assault on November 20. The first day’s invasion flotilla comprised three waves of amtracs followed by two waves of LVCPs carrying the three battalions of the 2nd Marines and the 2nd Battalion of the 8th Marines, which embarked on Heywood. During the final run to the beach the amtracs conducting the initial assault were to be arrayed in three waves or rows, with 42 LVT-1s in the first wave, 24 of the newer LVT-2s in the second wave, and 21 LVT-2s in the third wave.

Two-and-half hours after casting off from their transports, the assault waves began leaving the staging area near the transports to begin the 10-mile trek to Betio. The amtracs and LCVPs crossed Tarawa’s outer reef and entered the inner lagoon on a bearing that took them east and slightly south, roughly parallel to the island. The flotilla reached the line of departure, demarcated by the minesweeper Pursuit, roughly 9,000 yards from shore.

Larry and the coxswains in the other patrol boats, which were leading the way, stood on their engine hatches and gave the “flanker movement” signal––one arm up and one out, pointing at the island like a semaphore, signaling that the amtracs should execute a right turn and head for the beach. Larry in turn stood on the engine hatch of his boat and gave the same signal to the amtracs behind him. The time was 8:24 am.

The plan was for the boats of the first wave to go in, deliver their troops to the beach, and then turn around and come back out to pick up more troops from the follow-on waves of LCVPs standing farther out in the lagoon. The waves were supposed to be separated by300-yard intervals and while the first-wave boats were returning the second wave would go in, and then the third wave. This series of movements would be repeated until all the units assigned for the first day’s assault had been landed.

But it didn’t work that way. The entire group, all three waves, 25 to 30 yards apart, swung around to get into position for the landing. There was no firing from the island at that point. Larry recalled: “Then I gave the flanker movement for the first wave to go, everybody—all three waves—started to go, and suddenly I saw all these amtracs, 120 of them, coming right at me. Instead of three separate waves, there was only one wave now, everyone racing to see who could get there first.”

They passed by his boat and churned on toward the reef. Larry tried to separate the waves, driving among the amtracs, coming up alongside them and yelling at the drivers to maintain their intervals or to open them back up. To no avail: the drivers and the Marines aboard the amtracs yelled back at Larry, using what might euphemistically be termed “colorful” language to communicate their noncompliance.

About the same time that Larry was engaging in these lively conversations, the flotilla began taking fire from long-range automatic weapons, particularly antiaircraft guns. Airbursts from those guns blossomed nosily overhead but did no damage to the control boats and amtracs, and injured no one.

The flotilla reached the reef, where the control boats turned aside and halted. The amtracs plodded on by, clambering up and over the reef into the shallower water beyond. As the force drew near the hulk of the Nimonoa, a freighter half-sunk on the landward side of the reef, enemy fire suddenly increased in volume, intensity—and variety.

Shells screeched through the air and everywhere around them waterspouts erupted, hundreds of them. Near misses raised tall columns next to Larry’s boat, dousing him and his two crewmen. Any one of those shells could have destroyed a boat or amtrac, but they all missed. So far, so good. But not for long.

The Japanese opened fire and began to score hits on the amtracs, “blowing them to pieces,” according to Larry, who drove his boat right down the middle of the amtrac assault waves, weaving around the shattered boats and past the bobbing Marines who had spilled into the water. They were crying out, “Stop! Help! Wait!” Larry shouted back that he couldn’t stop, “and they told me in good four-lettered words what they thought of me.”

Larry’s boat carried a flamethrower unit and other special weapons people who were to be landed on the end of the so-called long pier, which extended some 600 yards from the shore all the way out to the fringing reef. On the way in, he briefly ran aground on the reef––this was how he learned that the tide would not cover the reef––but he was able to get the boat over the reef and continue to the pier.

The boat came under heavy fire as it approached the pier; bullets were flying everywhere and the noise was deafening. Then the cable mechanism for lowering the ramp was hit and after that Larry was unable to lower the ramp all the way down, so he cranked it all the way up. The boat struck bottom a few yards short of the pier and the men piled out over the side and pushed on to the pier. Some were cut down but most made it; several darted for cover under the pier.

Larry then paused briefly to get his bearings and in doing so he looked off to his right (west) at the battle zone encompassing the inner lagoon (inside the fringing reef), Red Beach 2 nearest him, and Red Beach 1 beyond.

Unfolding before him in that area was a spectacle of unimaginable violence and carnage. The Japanese guns, firing into preregistered zones, were scoring many hits on the charging amtracs. Larry saw amtracs that were completely obliterated upon being hit several times simultaneously from different directions. He saw the projectiles from the enemy’s bigger guns, balls of fire flying through the air, hitting the amtracs one after the other, producing fiery explosions that filled the air with an acrid reek and clouds of thick smoke. Marines with their clothes ablaze were leaping from these damage craft, only to be shot down instantly upon hitting the water.

He heard the splat-splat-splat of machine-gun bullets hitting the water near him and he watched as many Marines ducked under to avoid them. He also watched as other Marines, exhausted or past the point of caring, simply stood up and walked toward the beach. Many of these were cut down as they tried to get past barbed-wire entanglements in the shallows near the shore; that barrier was shortly festooned with dead and wounded Marines.

The wounded men screamed and begged for help but in most cases none was forthcoming—the corpsman who tried to help them being killed in the effort—and virtually all of them perished in the utmost extremes of misery and pain, draped over the wire or hanging from it, their bodies ripped open by the razor-sharp barbs and by the bullets striking them, spilling blood and guts—entrails and viscera, and any other internal organs so violently dislodged—into the reddening water.

Larry also watched in horror as other amtracs crawled up on the narrow beach and the Marines jumped out––even as the Japanese came storming out of their bunkers to engage them. There, on that narrow strip of sand in front of the seawall, the adversaries battled each other like dueling heroes in an epic poem, stabbing and slashing with knives and bayonets, clubbing with rifle butts, grappling with their bare hands, choking and punching and kicking.

What Larry saw on the beach and in the water around him changed his life forever. The savagery, the slaughter, and the transcendent heroism of both the Marines and the Japanese opened a spiritual door, permitting him to look directly into the vast mystery beyond. Many years later he explain it thus:

“I’ve been a minister for 40 years. And in my faith we believe God actually speaks to men: God calls men to the ministry. And I felt that when I was very small I was supposed to be a minister. Of course, I wasn’t living too good a life when I was in the service! But at Tarawa I remember driving along and first one of those amphibious tractors and then another would be hit. Some of them would explode and burst into flames and the guys were jumping overboard with their clothes burning—and we couldn’t even help them. We couldn’t go back.

“I remember talking to the Lord, and I said, ‘What about this idea of my being a minister?’ You know, you can’t have a 17-year-old talking to the Lord God of the Universe! But I was talking to him, and I was telling him, what about this thought of mine of being in the ministry? It seemed like I had the understanding that I would be a minister. And I said, ‘What if I’m shot? How could I minister if I couldn’t talk? How could I minister if I didn’t have any legs? What about a long recovery from being badly wounded to the head?’ And the Lord said to me: ‘Give me your faith.’ And, you know, I took courage from that.”

Larry Wade would need all the faith and courage he could get. After his passengers disembarked, he was supposed to get clear of the fire-swept zone. But when he saw all those wounded Marines struggling in the water, he decided to disobey orders, back the boat out, and pick up wounded men. Other coxswains, seeing Larry’s example, joined the rescue effort. It was then mid-morning, about 10:00 am.

A number of Marines who had been wounded in the lagoon managed to struggle into the reef and now stood on that coral shelf beckoning or calling for help. Larry went cruising along the reef, stopping to rescue each and every wounded man he encountered. He had a corpsmen on the boat and this man had his hands full, working hard and courageously. Some of the wounded they just plucked out of the water; it was a matter of simply cranking the ramp down as far as it would go and pulling them in, up and over the lip of the ramp.

Many of the wounded had been hit in the legs because they were standing up as they waded in and the enemy machine guns were set to graze just above the water’s surface. By the time Larry and his crew pulled them aboard, they had more or less stopped bleeding, the salt water having stanched their wounds. Sometimes Larry and the corpsman would wade out into the water with a stretcher and grab a man who was shot up and bring him in. They’d pull the wounded man aboard and the corpsman would cut the seam of his dungarees with a pocket knife all the way to the top, slicing through the belt loops, laying the dungarees open.

Some of the Marines were so badly torn up there wasn’t much they could do for them by way of applying bandages. If, for example, a Marine had a large hole in his chest, the corpsman stuffed it with gauze and sulfanamide.

Larry recalled picking up one Marine who had gashed his thumb on barbed wire. He was bleeding profusely and “carrying on about it,” so Larry packed the wound with sulfanamide powder, bandaged it, and gave him a shot of morphine. In the minutes that followed, he picked up more men, some terribly wounded, in agonizing pain, and close to death. Larry even took on the role of corpsman, treating them as best he could, administering morphine to each one.

Inevitably, he began to run low on morphine syrettes, and when the Marine with the injured thumb cried out for another shot, Larry yelled at him: “You just shut up! This morphine, by God, is for the badly wounded!” The wounded Marine didn’t say anything after that.

Larry watched as another amtrac loaded with Marines approached the end of the pier, billowing smoke from a hit to the engine housing. The amtrac’s coxswain, fearing that his machine was about to burst into flames, ordered his passengers into the water. He no doubt saw other Marines wading in waist-deep water alongside the pier and must have concluded that the water at the end was equally shallow. But in fact it was considerably deeper there because the bottom had been dredged to accommodate the unloading of bigger boats. Larry knew this and, as the Marines climbed onto the gunwales to jump, he cried out, “No! Don’t do it!” At the same time he began turning the crank that lowered his ramp.

Too late: the Marines jumped feet-first into the water and sank instantly under the weight of their clothing and gear. Some 18 Marines were on that amtrac and Larry said that every one of them drowned. Their unbuckled helmets came off and Larry watched helplessly as one of them descended, blond hair streaming, looking up at Larry with blue eyes anguished and puzzled.

“I see this guy just about every night in my dreams,” said Larry. “I’ve seen him every night for over 60 years, watching him go down, down, down, looking up at me through the water with his blue eyes, his blond hair just flying.”

When his boat was filled with wounded, Larry took them back to the troopship Heywood. Among the wounded was a sergeant who had lost his left leg about six inches below the knee. Larry offered him a stretcher to lie on, but he refused it, saying he didn’t want to lie down. “Save those stretchers for guys hurt worse than me,” he said. So he just stood there—stood—leaning against the side of the boat; he had tied off the stump with a tourniquet made from his boot laces, and every now and then he would twist the tourniquet with his bayonet blade. He hobbled on his one remaining leg all the way back to Heywood, and when they arrived at that ship he waited until everyone else had been taken off the boat before he got off, the last man off Larry’s boat.

Larry returned to the reef to resume rescue operations and made innumerable trips back and forth between the reef and Heywood. Late in the day, before nightfall forced a halt to his efforts, he came upon an LCM some distance beyond the reef, carrying a Sherman tank and heading toward the beach. Suddenly, one of the boat’s engines malfunctioned and the coxswain made a U-turn to get out of the kill zone and make the necessary repairs. While he was just sitting there, tinkering with the damaged engine, somebody in his boat found what looked like a five-inch shell on the deck. It had passed clear through the side of the LCM, just above the water line, just above the engine, which was covered by a flap made of corrugated metal.

Larry pulled his boat alongside the LCM. “You guys are pretty low in the water,” he told the coxswain.

The coxswain said, “Yeah. We’ve been hit, but I think we can make it. I’ve got to unload this tank.”

“Well, let me take a look at it,” said Larry.

Larry climbed aboard the LCM and found that the bottom was flooded; water was within two or three inches of covering the engines. The tank was in the well deck and the crew had put a chock of wood about six-by-six feet on both sides behind each track to keep the vehicle from sliding into the bulkhead. “While I was looking around, all of a sudden I heard this sound like a gun––BAM!––and the chocks popped out from under the tracks. The pressure had gotten so bad from slipping back in the boat, because the stern was starting to go down. The LCM’s three-man crew said they weren’t going to abandon their boat. But the Marine tank crew, they said, ‘We don’t care what this Navy crew does, we’re getting off!’ ”

Larry felt the same way. The Marines started piling into Larry’s boat and he went with them, pulling his boat away from the LCM. Then the LCM’s crew started yelling at him to come back so he returned and took them off, too. No sooner had crewmen gotten into Larry’s boat than water gushed into the LCM. The tank settled back and the boat went down stern first. The LCM settled almost vertically onto the bottom with its ramp sticking up out of the water. Shortly thereafter, someone set a bright green light on the part of the ramp that was above the surface––a signal to keep other boats from running into the LCM during the night.

On his final trip to Heywood, Larry was ordered to report to Sheridan, where he took aboard a unit of the 8th Marines. Around dusk, he joined the other boats carrying the rest of the 8th Marines in the vicinity of the green light on the ramp of the sunken LCM.

Nightfall brought no end to the horrors of the day, only a change in the form those horrors took. “That first night—and the second night, too—I could hear guys screaming,” Larry said, “guys that were in the water, screaming in the black of the night: and I know sharks were tearing them all to pieces.”

At around 2:00 am on November 21, an LCP (Landing Craft, Personnel), also designated #13, came alongside Larry’s boat. Smaller and speedier than the LVCP, but lacking a bow ramp, this craft was commanded by Lt. (j.g.) Edward Albert Heimberger, a 34-year-old movie actor known to the American public by his stage name, Eddie Albert.

Eddie was the salvage boat officer aboard Sheridan, responsible for controlling the ship’s landing craft. The job of salvage-and-control would be broadly interpreted at Betio; it would be accurate to say that his job entailed salvation as well as salvage, and that many Marines were the beneficiaries of his good work in that regard.

Eddie had spent the day with the 8th Marines’ boats, which had been lowered into the water in the late morning and early afternoon and had loitered just outside the line of departure while the assault waves were battling on the island. Now he told Larry that he had an LCVP loaded with ammo and medical supplies but that the crew was unwilling to take it in to the pier: would Larry and his crew do the job? Larry said they would, volunteering without hesitation. Eddie led them over to the other LCVP and, while Larry and his crew climbed aboard, the crew of that boat boarded Larry’s craft. Once the transfer was complete, Larry headed into the end of the pier.

They arrived at the pier but before they could tie up and start unloading, they began taking fire from an enemy machine gun. “It was aimed right at us,” said Larry. “That was the first time I was aware that someone was trying to kill me, specifically!”

Tied up alongside the pier, about 12 feet from the end, was a Japanese landing barge, a craft similar in configuration to the Higgins boat but with a distinctive round conning tower for the helmsman. The Japanese had been using it to haul diesel fuel and the bottom was awash in oil. Larry was trying to find a place to tie his line and, as he was doing so, a burst from the Japanese machine gun sprayed the pier. Startled, Larry lost his footing and he fell into the barge, landing on the oil-covered deck.

His uniform soaked in oil, Larry clambered back aboard his boat and secured it to the pier. He and his crew then began unloading their cargo. At one point, while they were passing ammunition from his boat up to the Marines on the pier, the fire got so intense that they got out of his boat and ducked under the pier for protection. When the fire slackened somewhat, they got back in and resumed unloading.

After they had finished emptying the boat, Larry and his crew climbed up onto the pier. There was more firing, coming from a wrecked amtrac in front of them, about 50 yards away. Evidently, a Japanese soldier had swum out to the vehicle and was spraying them with its machine gun.

Larry recalled, “You could see him plain as day, because all the island was on fire and the light from the burning fires illuminated the whole area. “And this one sergeant said, ‘Look, you guys, if you’re going to be here getting in the way, get a rifle and use it.’ So they handed me a rifle, and when this Jap in the amtrac started shooting at us, spraying us with a machine gun, I started firing back. Everybody on the pier started firing back.”

The Japanese machine gunner was finally silenced. Larry loaded all the wounded who would fit on board his boat and took them out to Sheridan. Then Eddie Albert came by and took him and his crew back to their original boat, #13. They found it near the green light beacon, lashed to another LCVP, filled with Marines but missing its crew. The Marines were in a miserable state.

Larry recalled, “The boat was a mess because so many of them had gotten seasick. They were shitting in their pants, urinating, vomiting. They would puke or shit in their helmets and sometimes they would throw the mess over the side but sometimes they’d just dump it in the boat. Making matters worse, the boat smelled like a slaughterhouse from all the wounded we’d been hauling around. This made everyone sicker, and the fact that they didn’t have anything to eat didn’t stop them from getting sick, and they were just splashing around in the mess at the bottom.

“One of them Marines was lying on the bottom and had rigged a headrest using a water can and a hand grenade. The water can shifted because of the movement of the boat and the pin came out of the grenade and the grenade armed itself and started to fizz. But the Marine just took off his helmet and slammed it over the grenade and in that way he somehow contained the blast and nobody got hurt. The blast kind of seeped out under the helmet, to the side. I thought surely it would blow a hole in the bottom of the boat, but it didn’t. Instead, it blew the stock off his rifle. He was worried about that—about not having a rifle when he went onto the island. But the other guys, they just said to go on in; there’d be plenty of rifles lying around.”

Just before dawn, Eddie Albert came by again in his control boat and said to Larry that they would soon be landing the 8th Marines in the center of the island on Red Beach 2. “It’s about time,” Eddie added. “These guys have already been through hell.”

At daybreak, the LCVPs carrying 8th Marines headed for the island, with Eddie’s boat leading the way. Upon reaching the designated line of departure, Eddie stood on his engine hatch and gave the flanker movement; Larry followed Eddie’s lead and gave the same signal to the boats behind him. The flotilla turned right and started for the shore. The Japanese opened fire and Larry watched as near misses raised tall columns next to Eddie’s boat, dousing him and his two crewmen.

Larry remembered: “My boat was one of the few that had been involved in the actions of the day before, so I had an advantage––I knew what to expect. When we got the order to form in line abreast and head in, I knew we were going to hit that reef. My boat was on the extreme left as we went in. We hit the reef and, again, because the ramp couldn’t be lowered, the guys piled out over the side; this probably resulted in fewer casualties than guys who went straight out on the ramps of their boats. They were close to the pier, and they headed right for it and found some protection there.”

After they disembarked, Larry was able to back his boat off the reef without any difficulty: “It just slid right off.” Because he was from another ship—Heywood, not Sheridan—he felt that he was now relieved of his responsibility for taking men in. And because he had not reported to his ship since the beginning of the operation the day before, he headed out to find Heywood. When he got to the ship, he was given four drums of gasoline and told to take them back to the pier. He said:

“But we didn’t quite make it there. Eddie Albert, he had been picking guys up off the beach, and his propeller had been bent. And he saw my boat come chugging along and he waved me over to his boat. He said, “We’re going to have to take your boat.” And I said, “No, you’re not going to take my boat.” I said, “I’m the captain of the boat, I’m in charge of it.” He says, “Well, I’m the salvage officer.” I don’t know what he was salvaging; it ended up he was salvaging bodies more than anything else. Anyway, he said, “We have to have your boat. And I said, “Well, then, I’ll go with it.” And he said, “That’s fine.” We decided that we would not exchange crews. So Eddie climbed aboard my boat along with two or three corpsmen, and his boat, with his crew aboard, took off and headed back toward Sheridan to get the prop fixed.

It was now about mid-morning and the 8th Marines were in the water, taking a terrible beating. Eddie told Larry, “We’ve got to go pick up guys out of the water; they’re all around, they’re dying in the water.” There were several other boats in the area and Eddie boarded one of them. Then the boats rushed in together to pick up the wounded. “But the Japanese recognized what we were doing,” said Larry, “and they opened up on us and it was just like all hell was breaking loose.

“They were firing at us point blank. Meanwhile, in the midst of this fire, Eddie would point to this wounded man and that one, directing us to them, and we would pull up alongside the man and haul him aboard. We’d take them over the side: remember, I couldn’t lower the ramp because the mechanism was damaged. But even if the ramp had been in working order, I couldn’t have lowered it because the boat was too heavily weighted by those four gasoline drums we were carrying and sitting too low in the water as a result.”

All the while, as they pulled wounded Marines in over the side, Larry could hear bullets striking the metal armor plate on the outside. Some of the rounds were armor-piercing and came right through the side of the boat and would spin around on the deck. Some hit the gasoline drums but, luckily, passed right through them without igniting the fuel. Meanwhile, Larry’s machine-gunner was blasting away with his twin-thirties at Japanese machine-gun nests in the wrecked amtracs and aboard Niminoa. The enemy machine gunners on Niminoa were actually behind and above Larry’s boat, shooting down at it.

The “gang approach” of going in with several boats all at once to pick up the wounded didn’t work out. “The Japs just poured fire into us,” Larry noted. “The fire was so intense that Eddie yelled to the other guys, ‘Get out of here!’ And they got out, driving out beyond the range of the enemy’s machine guns. With his boats all gathered together, Eddie told his coxswains that they were going to have to go in one boat at a time and pick up whatever wounded they found and bring them out and load them into the LCVPs or LCMs waiting out of range.

Eddie organized a shuttle system whereby each boat, when it was fully loaded with wounded, transferred its charges to another boat that took them to Heywood. Eddie’s LCP was smaller than Larry’s LCVP, so when his boat was filled he would come alongside Larry’s boat and transfer over his wounded Marines. Usually the transfer was made beyond the reef––and beyond the range of Japanese guns––but not always.

Larry recalled that at one point, “After we had picked up quite a few guys, and Eddie had transferred a load of wounded from his boat to mine, he shouted across to me, ‘Well, I think we’ve done pretty well. None of the crews have been hit.’

“At the time we were under heavy fire and I yelled back, ‘Well, be careful—and don’t move!’ And he said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Well, look down between your legs.’ The construction inside the boat was plywood; the metal was on the outside. His boat and mine were just then taking hits: armor-piercing rounds were tearing through the metal and ripping up the wood, scattering it all over the boat—even as we were talking, the debris was just flying, the wood is splintering from rounds piercing the side of the boat, and the rounds are flying around in the boat and they’re still hot. I told Eddie that he’d better not move or he would be singing soprano in the choir! I don’t know how in the world we both avoided getting hit. I think it was the Lord who was protecting us.”

It was on one of Larry’s rescue trips that 1st Lt. Dean Ladd, a platoon commander in B/1/8, had been hit in the abdomen several hundred yards from the beach. Two of the enlisted men in his platoon had helped him reach Larry’s boat.

Ladd remembered that several wounded men and their rescuers were clustered in front of the partially raised ramp. He said, “One by one, the wounded men were half-pushed, half-flung over the top of the ramp, after which they rolled down the ramp onto the deck. The man next to me was a big fellow with a ravaged face. His wound was terrible, worse than mine. I motioned for him to go before me and he was boosted to the top of the ramp. Then it was my turn and the two privates from my platoon lifted me. I was groaning, really hurting, and my helpers couldn’t quite get me over the top of the ramp: I was limp and heavy, a bulky sack of flesh and bone with a hole in it, and they just couldn’t manage to raise me high enough. Then the Marine with the ravaged face reached down and grabbed me, and one-armed me into the boat.”

Dean tumbled, groaning, down onto the deck alongside the man with the bloody face.

“The deck was covered with maimed and wounded men, their bodies bandaged and bloody, many writhing in pain, many groaning just like me.”

The last Marine Larry rescued on this particular trip to the reef was Ken Desirelli, a 19-year-old private first class from C Company. After jumping off the ramp of his LCVP, he had headed toward the distant beach in waist-deep water, hunched over to make himself a small target. But not small enough.

He had gone about a hundred yards when he was hit. “I felt like somebody had walloped me in the right shoulder with a baseball bat,” Desirelli recalled. “And I said to myself, ‘What the hell’s that?!’ Then I saw that I was bleeding and I knew I’d been hit.”

But he pressed on—“because that’s what I was supposed to do. Then I began to think, jeez, I wanna go to sleep. I wanna lie down. But I didn’t stop and I still had my rifle because I knew that I’d be charged fifty bucks if lost it. That was the main thing that worried me at the time.

“Meanwhile, I’m getting sleepier by the second and my gear is getting heavier. I slipped it off my back and dropped it in the water. I kept going. I wasn’t feeling any pain. Now I’m thinking, jeez, it sure is a long ways in there. Then, for no particular reason, I began to wander off toward my right, toward the Niminoa. I was just wandering about, standing upright, and I saw bullets hitting the water all around me and I couldn’t care less about them. They didn’t seem to matter much because they weren’t affecting me at all.” Then he looked around and saw a Higgins boat––Larry Wade’s boat––with its ramp halfway down and he thought, “Maybe I ought to go over to it.”

But the boat seemed so far away and Ken wasn’t sure he could make it—he wasn’t sure he wanted to make it. He was becoming increasingly lethargic and indifferent to his fate: death was creeping over and through him. He later speculated that “it would have been easy for me to just give up and die at this point. I was bleeding a lot and in shock and all I wanted to do was lie down and go to sleep. But I made my way over to the boat and, as I got close to it, I could see that they were getting ready to raise the ramp. And I hollered, ‘Hey, wait! Give me a ride!’

“I went over to the ramp but I couldn’t pull myself up because my arm wasn’t working. So I put my rifle on the ramp and this big guy reached down and grabbed me and lifted me aboard. He was wounded in the face and head and he was all bandaged and bleeding a lot. But he just grabbed me with one arm and picked me up and pulled me in. With one arm! I rolled down the ramp and passed right out.” His rescuer was the same badly wounded Marine who had hauled Ladd aboard.

Larry delivered Ladd, Desirelli, and the other stricken Marines in his boat to Sheridan, then returned to the battle zone to pick up more wounded. His boat still had the gasoline drums aboard and he took them into the end of the pier to unload them. Just as he was unhooking the ramp catch on his boat, a sniper round struck his helmet and knocked him down into the well deck. The bullet made a hole in his helmet but, incredibly, did not penetrate his skull; he was okay. “But I was addled for about 30 minutes after that.”

Wade continued to work. In the afternoon, the tide started coming in and he took his boat up the channel alongside the pier to the shore to fetch a load of wounded from the island itself. He landed right about where the pier juts out from the land and walked up on to the beach, stepping over the dead bodies at the waterline. He came across maybe 50 stretchers, all with corpses on them and all with red tags with “DEAD” attesting to their state.

But as he walked past the stretchers he distinctly heard a voice say, “I need a drink of water. I need a drink … need a drink … need a drink.” He stopped and looked around but the dead men on those stretchers remained silent and unmoving. Later, when he recounted this incident to his buddies, they told him he must still have been in shock from the bullet that hit his helmet and that he had been hallucinating. Larry admitted that this might be the case, but he could never be sure: the clarity of the voice as it spoke to him—and which would haunt his thoughts for the rest of his life—argued for another explanation.

Larry spent the rest of the day helping to load wounded Marines into rubber rafts and then walking the rafts down the channel to LCVPs that waited out there for them. There was no shortage of wounded and Larry and others worked as fast as they could, “just piling guys on those rafts.”

At some point during his endeavors, he saw a bloody 1st Lt. William Deane Hawkins standing by a big bunker, talking with some of his fellow officers. Hawkins was the commander of the 2nd Marines’ scout-sniper platoon, which had seized the long pier at the start of the battle, in advance of the landings on the assault beaches. While leading his unit in attacks on Japanese pillboxes and strongpoints, Hawkins had suffered multiple wounds from shrapnel and had been shot through the chest. He had also personally wiped out nine pillboxes or machine-guns nests while suffering from his wounds.

Larry could hear his subordinates urging him to go to an aid station, but Hawkins refused and Larry moved on. Hawkins died from his wounds shortly thereafter. His commanding officer, Colonel David M. Shoup, who earned the Medal of Honor at Tarawa, later called Hawkins an “inspiration,” and said, “It’s not often you can credit a first lieutenant with winning a battle, but Hawkins came as near to it as any man could.”

Hawkins was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on Betio, as were First Lieutenant Alexander “Sandy” Bonnyman Jr., and Staff Sargent William James Bordelon

The battle ended anticlimactically for Larry Wade. By first light on the third day, he still had not gotten any sleep since the operation began and was running on adrenalin and nervous energy.

Larry doesn’t remember what happened during most of the third day—he thinks he was still in shock from having been struck in the helmet by a bullet. The next thing he remembered was that it was late afternoon and his boat was just sitting off the end of the pier. A group of 6th Marines came down the pier and asked Larry for ride to the small island just east of Betio. Larry took them over and, by the time he returned to Betio, the battle was well and truly over. He spent the night in his boat.

The next day was Thanksgiving and even then most of the Marines were gone. A calm had settled over the island. “I remember taking a bath, just washing off, on the beach, a nice, quiet, sandy beach,” said Larry. “Somebody had taken a load of foodstuff over, and there was canned salmon and canned tomatoes, and we ate them all.”

At length he took his LCVP back to Heywood. When he boarded the ship, the captain took Larry and his crew down into his quarters and started crying. Larry recalled that the captain said, “I thought you guys had been killed. I never have lost anybody.” He wanted to know what they had been doing for the past three days, and Larry filled him in.

The next day Larry, still woozy from his head injury, transferred to the USS J. Franklin Bell (APA-16). “Somebody took me over there—I don’t know even how I got there. All of my seabag and everything had been packed up for me. For some reason, I had to go to sickbay; I still don’t remember why. I remember there was a cut on my head. Evidently that bullet had done something. In my service record it says that I had a concussion. Anyway, I found out that [the Bell] was to be my home. And we were going to operate salvage operations from there.”

When Eddie Albert finished taking the last of the wounded out to the ships, he got his boat back; the propeller had been repaired. But by then the action was over. (After the war, Eddie Albert went back to Hollywood to continue making films––including such war films as The Longest Day, Attack!, Bombardier, and Captain Newman M.D.––and the television series, Green Acres. He passed away in 2005.)

On Eddie Albert’s recommendation, Larry subsequently received the Navy Commendation Medal for “Bravery and Outstanding Performance” during the battle for Betio.

“Coxswain Wade was wonderful!” Eddie later said. “Without any armor protection, under heavy enemy fire, he had to stand up and steer the boat, keeping her steady against the strong current, and avoid grounding on the coral. If that wasn’t enough, he had to carefully hold the boat off the wounded men who had dragged themselves alongside to be lifted aboard. If it weren’t for Wade, a tall, young squirt from Texas, I don’t think we would have saved a man.”

Larry stayed on Betio for eight months. “Any time they needed a crew—coxswain, motor machinist, seaman—they’d tell us ahead of time and a C-47 would take us to our destination. If they needed us in the Marshals, they’d come get us. And we’d join the invasion, and make the landing. I was in two different landings in the Marshalls. And I was at Saipan. I was taken off of Saipan and flown to Hawaii and put aboard an LST to make the landing at Leyte. I was in danger 17 times, but Tarawa was the roughest operation.”

For its duration, Operation Galvanic and the battle for Tarawa was one of the bloodiest and most savage operations of the Pacific campaign. The U.S. Marine Corps lost 990 men killed and 2,296 wounded during the three-day fight, and 687 U.S. Navy personnel died. Of the 5,000 Japanese and Korean defenders, all but 147 perished. Many American commanders felt that Tarawa was a costly battle that didn’t need to be fought, that it could have been bypassed and left to “wither on the vine,” to quote Marine General Holland M. Smith.

Like the Marines who stormed ashore protected by nothing but a khaki shirt, brave sailors––like Larry Wade––who crewed the landing craft that carried the Marines into battle, were equally exposed to the hazards of battle, equally unprotected, and equally courageous.

In an interview with the author nearly 60 years after the war, Larry observed that “everybody at Tarawa who was there in any capacity was a hero––whether he wanted to be or not.”

Larry was too modest and too humble to include himself in that assessment; his intention was to pay tribute to sailors and Marines with whom he served. But the record speaks for itself, and there can be no denying it: at Betio, Larry Wade was a hero.

Lawrence Hugh “Larry” Wade passed away on November 8, 2007, in Norman, Oklahoma. Speaking at his funeral, Larry’s son-in-law, Steven Motsinger, observed that Larry was a hero three times over: “A hero to his country, a hero to his faith, a hero to his family.”

One would be hard pressed to come up with a more fitting epitaph for the “tall, young squirt from Texas” who saved so many lives in one of this nation’s most difficult battles.

Great recounting of the action at Tarawa. Larry Wade exemplifies the best of the American military. So glad I got to read his story.