By David Alan Johnson

“I say, better wake up.”

Red Tobin opened one eye, rolled over, and found his squadron mate, Pilot Officer John Dundas, shaking him by the shoulder and staring into his face.

Eugene Quimby “Red” Tobin had spent the best part of the previous night in a pub with his fellow American, Vernon “Shorty” Keough, and did not feel very much like waking up. The hut was dim and cold, his bed was warm, and he was still half asleep. He groggily demanded why the hell he should get out of bed at that exact moment, when the world was still dark and he could not even get his eyes to open.

“I’m not quite sure, old boy,” Dundas calmly replied. “They say there’s an invasion on or something.”

This struck Red as an excellent reason, although he was as impressed by the coolness of Dundas’s reply, even in his semi-conscious state, as he was by the news of an impending invasion of England. He got out of bed and looked out the Nissen hut’s window for any sign of life or activity. Through the dawn’s early gloom, he could barely make out the silhouettes of 609 Squadron’s Spitfires against the brightening sky, along with a few other huts scattered around the station at Warmwell, in Dorset, northeast of Weymouth on England’s southern coast. There was certainly no sign of anything as dramatic as a German invasion.

Actually, Red Tobin had a good reason for complaining about being rousted out of bed at the crack of dawn. The Germans did not have anything in the air at that time of day. Except for a few early reconnaissance flights, the Luftwaffe did not even begin to stir until late that morning, Sunday, September 15, 1940. The American volunteer could have safely gone back to bed for a few more hours and would not have missed a thing.

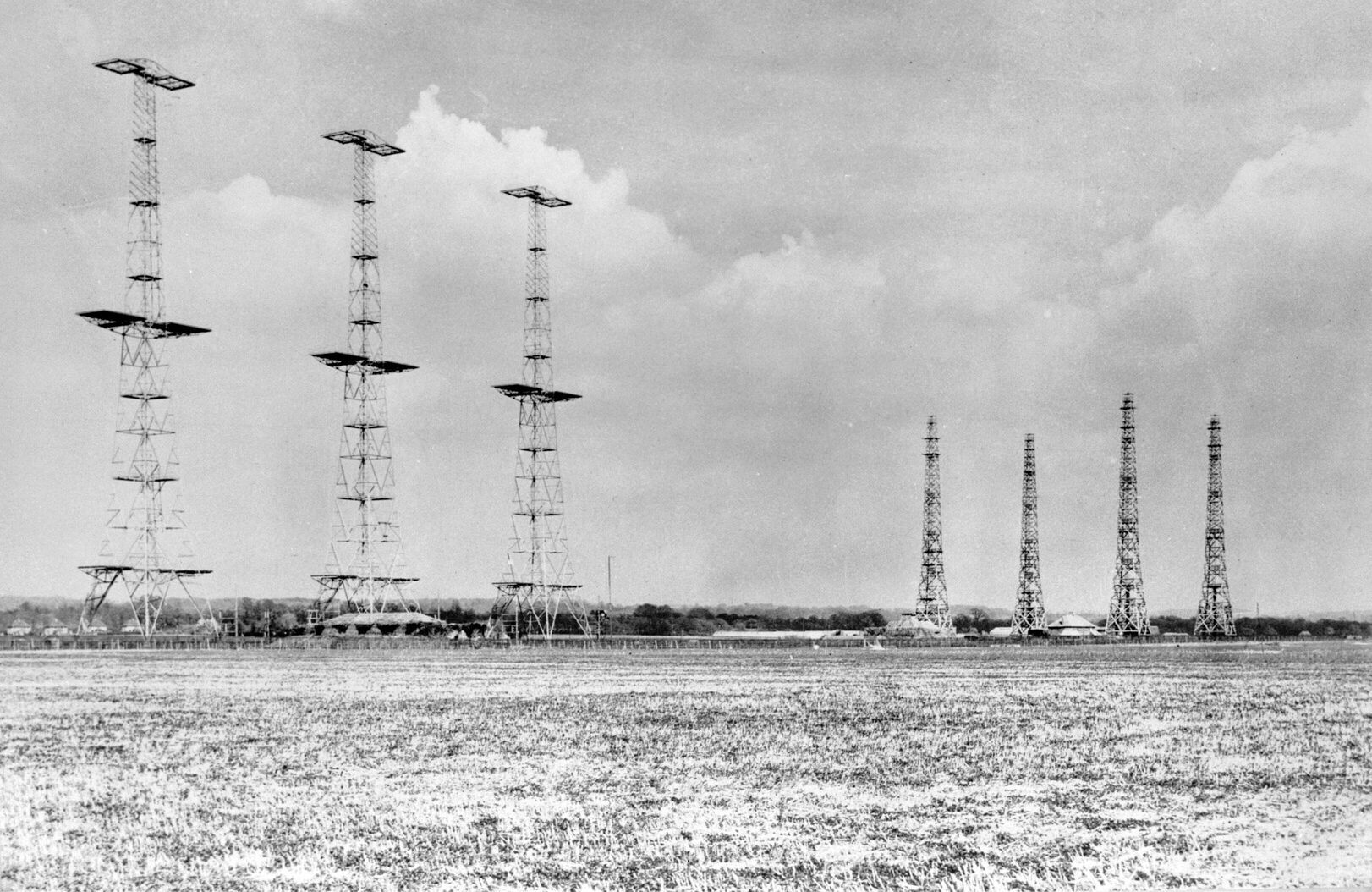

British intelligence had intercepted heavy radio traffic from Luftwaffe aerodromes, which alerted RAF Fighter Command that they could expect a maximum effort later in the day. But radar stations along the Channel coast did not begin to plot formations of German aircraft until 11 am, 40-plus aircraft followed shortly afterward by a smaller formation, then another 40-plus. At about 11:30, the formations joined up and began heading north toward the south coast of England.

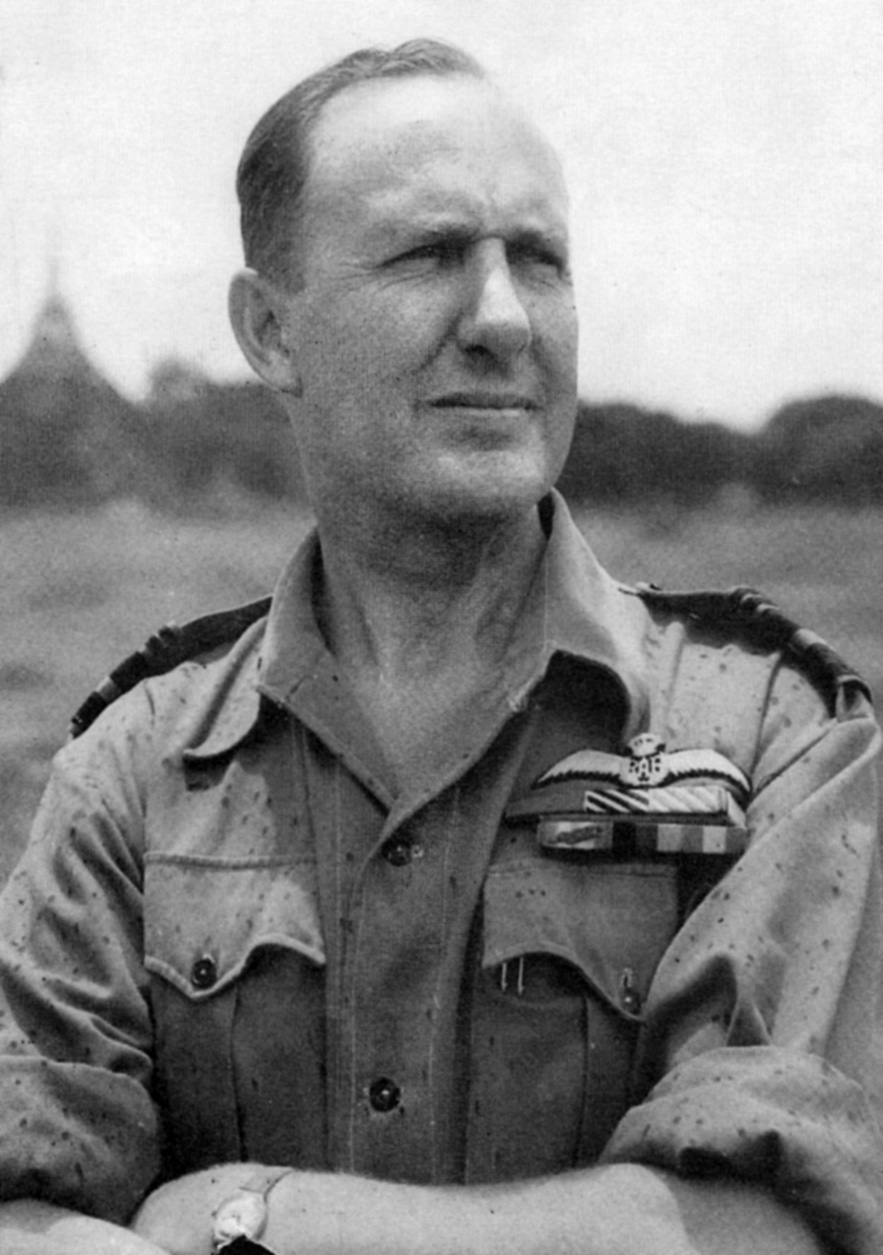

The warning gave 11 Group, which defended the approaches to London and the southeast coast of England, about 30 minutes to get ready. By the time the Luftwaffe had formed up and began making its way toward the Channel coast, 17 RAF fighter squadrons were in position—including five squadrons from 12 Group, bordering 11 Group on the north, which were led by the well-known Squadron Leader Douglas Bader.

At 11 Group Headquarters in Uxbridge, Middlesex, the excitement had begun at around 10:30, an hour before the first warning, when Prime Minister Winston Churchill dropped in for an unannounced visit. The PM went down to 11 Group’s bomb-proof operations room, nicknamed “the Hole,” to see if anything was happening. The Hole was situated 50 feet below ground, just off Hillingdon golf course. At 10:30, no one was exactly sure what was going to take place that day—it was too early to tell. But by noon the Luftwaffe had finally shown its hand.

The first group of enemy aircraft, about 200 planes, began crossing the south coast of England just before noon. Churchill watched the incoming raid being plotted on the great table map of England and said to Air Vice Marshal Sir Keith Park, commander of 11 Group, “There appears to be a great many aircraft coming in.”

Park had a quick answer: “There’ll be someone there to meet them.”

There certainly was someone there to meet them—five squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes, including 609 Squadron from RAF Warmwell. Red Tobin heard the voice of Squadron Leader Horace Darley over his headset: “Many, many bandits at 7 o’clock.”

Tobin glanced that way and saw about 50 Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters several thousand feet above and 25 Dornier Do-17 bombers about 1,000 feet below. Tobin’s flight, Red Section, was preparing to attack the Dorniers in spite of the Messerschmitts overhead.

Tobin was assigned the unenviable position of “Ass-End Charlie.” In the three-man Spitfire formation, Ass-End Charlie’s job was to weave and turn behind the section and his wingman, protecting them from attack from behind. The only problem was that there was no one to warn if enemy fighters were attacking his tail, which is why Ass-End Charlie did not enjoy a long life expectancy (and which is why the three-man formation was later abandoned in favor of the much more practical “finger four” formation).

Before diving on the Dorniers, the leader called Tobin: “OK, Charlie, come on in.” But before joining up with the other two Spitfires, Red executed one more weave. As he swung his Spitfire around, he caught sight of three yellow-nosed Me-109s closing in fast from astern.

“Danger, Red Section! Danger! Danger! Danger!” Tobin shouted into his microphone—loud enough, he thought, to be heard back in Kansas. His leader peeled off to starboard, his wingman climbed to port, and Red threw his Spitfire into a 360-degree turn, exerting heavy G forces on his body. He knew that the German pilots would never be able to pull out of their dive in time to shoot him; they would not get him if he kept turning.

The Messerschmitts shot past in their dive, just as Red had calculated. As the last one passed him, he was able to get his gunsight on it long enough to fire a burst. As the three Me-109s disappeared, he saw smoke trailing from the one he had shot at. Red felt his blood pounding—it has been a close call.

The Luftwaffe bomber formation, escorted by Me-109s and Me-110 twin-engine fighters, made its way steadily toward London. To some onlookers on the ground, the approaching aircraft resembled swarms of insects. Pilots of the RAF squadrons had a completely different impression of the enemy aircraft—they were overwhelmed by the sheer number of them. Red Tobin could see about 100 German planes. Within minutes of the first interceptions, the sky over Kent was filled with individual fights, smoking aircraft, and parachutes.

Number 609 Squadron had its hands more than full. John Dundas, who had shaken Red Tobin awake a few hours earlier, shot down a bomber over Kent, made another attack on a Dornier, and managed to evade several Me-109s—all within a few minutes. Andy Mamedoff and Shorty Keough, Red Tobin’s fellow American volunteers, shot up a Dornier along with four other Spitfires. Each claimed one-sixth of a bomber.

Red Tobin’s morning had not ended after his altercation with the three yellow-nosed Messerschmitts. In fact, it was just beginning. After pulling out of his 360-degree turn, Red caught sight of a Dornier making a shallow dive; the pilot had escaped several other British fighters and was headed for the safety of cloud cover. Red pushed the stick forward and dove after the bomber. He knew he would never be able to find it once it reached the clouds.

He pulled out of his dive and lined up the bomber in his gunsight. Immediately after pressing the firing button on the Spitfire’s control column, Red saw the Dornier’s port engine take hits from his six .303 machine guns. White smoke began pouring from the stricken engine. Either the radiator or the glycol tank had been punctured.

Red lost the bomber momentarily and had to come around again. On this run, he approached the Dornier from the starboard side. He held the gunsight on the starboard wing, pressed the firing button down for several seconds, and watched as bits of aileron and wing blew off.

The stricken bomber dove into the clouds while Tobin chased it through the overcast and saw it crash-land in a field. It hit the ground, ploughed its way across the grass, and came to rest with a bone-jarring stop. As Red circled the wreck, three crew members made their way out of the fuselage and sprawled across the still-intact starboard wing.

But Red was not absolutely certain that this was the Dornier he had brought down. He had lost sight of his victim as it passed through the clouds, and he could see another Dornier in another field about a quarter mile away. He could also see the wreckage of a Spitfire, a Hurricane, and an Me-109. Beyond these, he could see other wrecks from other combats.

There were certainly enough individual fights going on at the same time as Red Tobin’s. The entire southern route to London, from the Channel coast to the city’s southern boundaries, was one continuous battleground. While white contrails criss-crossed the blue sky in a mad pattern of brush strokes, civilians on the ground stopped what they were doing and gaped at the aerial jousting taking place overhead, looking in wonder at the profusion of descending parachutes and falling airplanes.

Most of the bombers reached London, as they had been doing since they began the Blitz on that city on September 7, and unloaded their bombs. Explosions could be heard throughout the city. One bomb damaged the queen’s apartments at Buckingham Palace; neither Queen Elizabeth nor King George VI were in residence at the time.

By this time, the Messerschmitts were beginning to run low on fuel; the red warning lights started coming on, telling the pilots that it was time to turn back toward their bases in France. As the fighters turned toward the south, they left the bombers very much on their own.

For the crews of the Heinkel He-111s and the Dorniers, the timing could not have been worse. At about the same time that the Me-109s began breaking for home, Douglas Bader’s “Big Wing” from 12 Group arrived on the scene: five squadrons, 59 fighters. They arrived later than expected as getting five squadrons into position required a lot of time. Keith Park had been insisting that Bader’s Big Wing was not really a practical way to employ a fighter defense. Bader responded that he was late because he had not been given enough warning.

Not every Messerschmitt had departed for France when Bader and his Big Wing reached Kent. Squadron leader Jack Satchell of 302 (Polish) Squadron observed that “a number of 109s” were still with the bombers and that they “attacked us as soon as we arrived.” But they soon had to turn back, allowing Bader’s wing to pounce.

One of the most famous air combats of the day, as well as one of the most publicized by the Ministry of Information, was led by one of the Big Wing’s squadrons. Flight Lieutenant Jessard Jefferies of 310 (Czech) Squadron attacked a Dornier over London along with three other Hurricanes. Jefferies set the bomber’s port engine on fire. His three squadron mates followed close behind, chopping away at the Dornier with bursts of machine-gun fire.

With one of its engines shot away, the Dornier, piloted by Oberleutnent Robert Zehbe, was now an easy target. Two Spitfires from 609 Squadron, flown by Pilot Officer Keith Ogilvie and his wingman, also went after the bomber. At this time the bomber’s two surviving crew members wisely decided to abandon the stricken plane.

Only the gunner, who was either dead or badly wounded, remained on board. Zehbe was still at the controls when Sergeant Ray Holmes of 504 Squadron came across the smoking airplane and attacked. Zehbe bailed out during Holmes’ attack.

Almost immediately after Zehbe jumped, the now abandoned Dornier (except for the presumably dead gunner) went into a violent spin and broke into two sections. The tail section fell on a building on Vauxhall Bridge Road in Westminster. The forward half, minus the outboard segments of both wings, crashed into the forecourt of the huge Victoria Railway Station in the heart of London.

Holmes’ Hurricane also went into a spin immediately after he fired his burst at the Dornier. He bailed out, landing either in a garbage can in Ebury Bridge Road, Pimlico, or on a rooftop in Chelsea, depending upon which source is consulted. Oberleutnant Zehbe parachuted into the London district of Kensington, where he had to be rescued from a crowd of outraged civilians. He later died of the injuries he received during the battle.

The press gave full coverage of the incident, with the assistance of the Ministry of Information. The story printed in the newspapers was that Oberleutnant Zehbe’s Dornier was the airplane that had bombed Buckingham Palace. Pilot Officer Keith Ogilvie was given a personal commendation by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, who had been a guest at the palace. She thanked Ogilvie for his courage.

A photo of the crashing Dornier appeared in newspapers and magazines throughout Britain and the United States. It was a particularly dramatic picture, taken as the bomber, its tail section and the outboard sections of both wings clearly missing, plunged toward Victoria Station. One of the American releases identified the wrecked bomber as “believed to be the plane that bombed Buckingham Palace on the 15th.”

By this time the Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons were returning to base for refueling and rearming, although four squadrons still had enough fuel and ammunition left to harass the retiring German bombers all the way to the Channel coast. As the fighters touched down, the “At Readiness” lights on the tote board of 11 Group Headquarters began to go out.

Prime Minister Churchill, who had been watching the battle on the operations room map of England, asked Air Vice Marshal Park, “What reserves have we?”

Park replied, “There are none.”

If the Luftwaffe high command had sent another strike at that particular moment, while the RAF fighters were still on the ground, the Germans would have had the upper hand. The bombers would have left their French bases before the Spitfires and Hurricanes were ready and would have been halfway to their targets before the British fighters could have been scrambled. But the Luftwaffe would not have another attack ready until the afternoon, and the opportunity disappeared.

Red Tobin approached the grassy runway at RAF Warmwell with a destroyed Dornier to his credit and about seven gallons of gasoline left in his tank. He made a good approach but did not see the crash wagon charge out from behind a hangar and into his path. One of his wheels hit the top of the wagon, snapping it back into the well of the fuselage.

The landing wheel was jammed in the “up” position. Red had no choice but to land on one wheel—he did not have enough fuel to do anything else. The one-legged landing badly damaged the Spitfire. It would eventually fly again, but not before some extensive repairs. But the accident meant that Red was grounded, at least for the rest of the day. RAF Warmwell was only a satellite field; there was no extra Spitfire on the base for him to fly.

At bases throughout 11 Group, as well as at Debden in 12 Group, the pilots straggled in. After touching down, they returned to their dispersal huts, where they reported to their intelligence officers and filled out combat reports.

While this was going on, the Spitfires and Hurricanes were checked over by their riggers, fitters, and armorers. Fuel tanks were refilled by squat tank trucks called “petrol bowsers,” and armorers replenished the .303 Brownings with long belts of ammunition. The fighters were also checked for bullet holes and battle damage.

Everyone was certain that the Luftwaffe would be back that day. Pilots tried to relax by reading, kicking a football around, or trying to get some sleep. But when the Tannoy loudspeaker made its first metallic click, even before any announcement was made, the pilots’ overstretched nerves jarred them to full alertness.

About an hour after the last of the Luftwaffe raiders landed back at their French bases, radar stations on the south coast of England began plotting another German buildup over the Continent. The announcement to scramble came at about 1:45 pm for a dozen fighter squadrons, sending the exhausted pilots scrambling once more for their Spitfires or Hurricanes.

The usual scramble took only a couple of minutes from the first terse announcement to actual takeoff. A group of high-ranking American officers had been at RAF Hendon that morning specifically to see how long a scramble actually did take. They used stopwatches to time 504 Squadron’s Hurricane pilots in their rush to intercept. The 12 Hurricanes got away in four minutes and 50 seconds.

The Luftwaffe formations began crossing the English coast at about 2:15 pm. Each formation consisted of between 30 and 40 bombers and twice as many fighters—both Me-109s and twin-engine Me-110s. In spite of the fighter escort, or maybe because so many of the escorting fighters were the lumbering Me-110s, the Spits and Hurricanes managed to break through to the bombers.

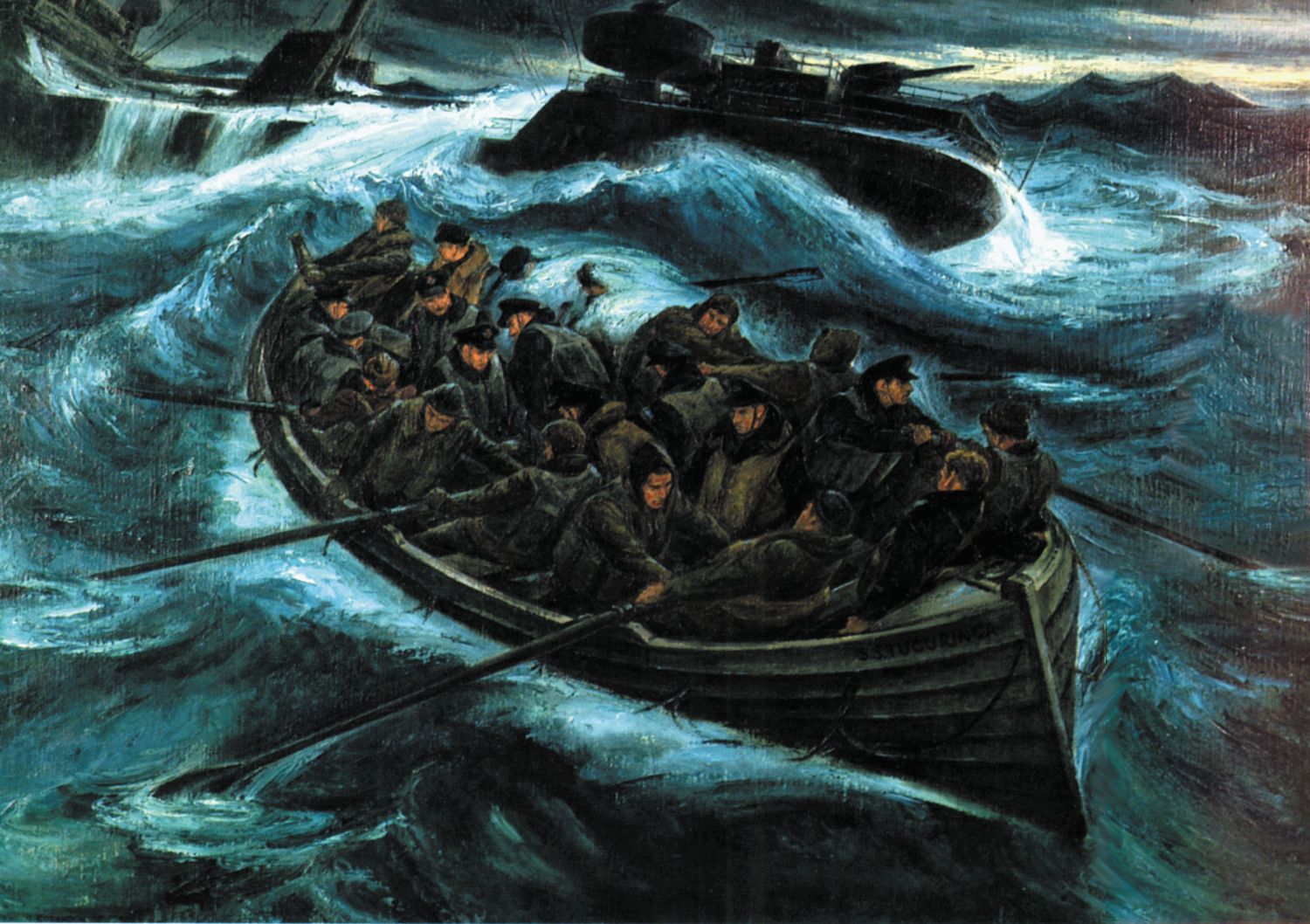

The Hurricane pilots of 605 Squadron closed with a formation of Dornier medium bombers over Maidstone, Kent. Pilot Officer Michael Cooper-Slipper felt his Hurricane shudder when a German gunner hit its fuselage. He reached the conclusion that his fighter had been fatally damaged and decided to attack the bombers by ramming.

Calmly and deliberately, Cooper-Slipper aimed his Hurricane at the middle aircraft of a three-Dornier formation. He flew straight into the bomber and was surprised by the easiness of the crash—not a violent collision at all, just a dull thud. The Hurricane’s port wing broke off, and Cooper-Slipper miraculously bailed out. As he jumped from the cockpit, he had a fleeting impression of the Dornier falling away.

It took more than 20 minutes for him to descend 20,000 feet by parachute. He came down in a hop field and was nearly lynched by farm hands who thought he was German. When the police eventually arrived, the field hands fought to keep Cooper-Slipper in their own custody. By that time, they had discovered that he was an RAF pilot and did not want to give him up.

Eventually, Cooper-Slipper did arrive back at Croydon. The driver who had been assigned to take him back to base stopped at every pub along the way. At every pub, the patrons bought him drinks—it was not every day that they had the chance to drink with a real, live RAF fighter pilot. By the time Cooper-Slipper reached Croydon, he was so drunk that he could hardly walk.

A second wave of German aircraft reached the coast at about 2:30; a third wave arrived about 10 minutes later. Each wave was made up of about 60 aircraft, and each formation headed directly for London.

This time the intercepting Spitfire and Hurricane pilots found that the bombers were being protected by a very determined escort of Me-109s. The RAF pilots tried their best to press through the screening Messerschmitts, but the German fighter pilots would not allow them anywhere near the bomber formations. Within five minutes, 303 (Polish) Squadron lost two of its Hurricanes along with five more damaged. By the end of the day, only four of the squadron’s 12 fighters would still be serviceable.

But many of the bombers had missed their rendezvous with their fighter escort and began circling in the vicinity of Maidstone. Apparently, they were waiting for the Messerschmitts to appear—which gave the RAF squadrons time to form up and move into position. By the time the Me-109s arrived, an estimated 170 Spitfires and Hurricanes were ready to make their attacks. Another 60 fighters, Douglas Bader’s Big Wing, reached the formations just before the red warning lights began to appear on German instrument panels, indicating that only 15 minutes of fuel remained.

A good many of the bombers made their way to London, as they always did, and bombs fell into districts throughout the city. Specific targets were not pinpointed; bomb aimers released their loads at random. Train service in and out of London was reduced to a near crawl; telephone and telegraph lines were damaged; hundreds more Londoners were made homeless.

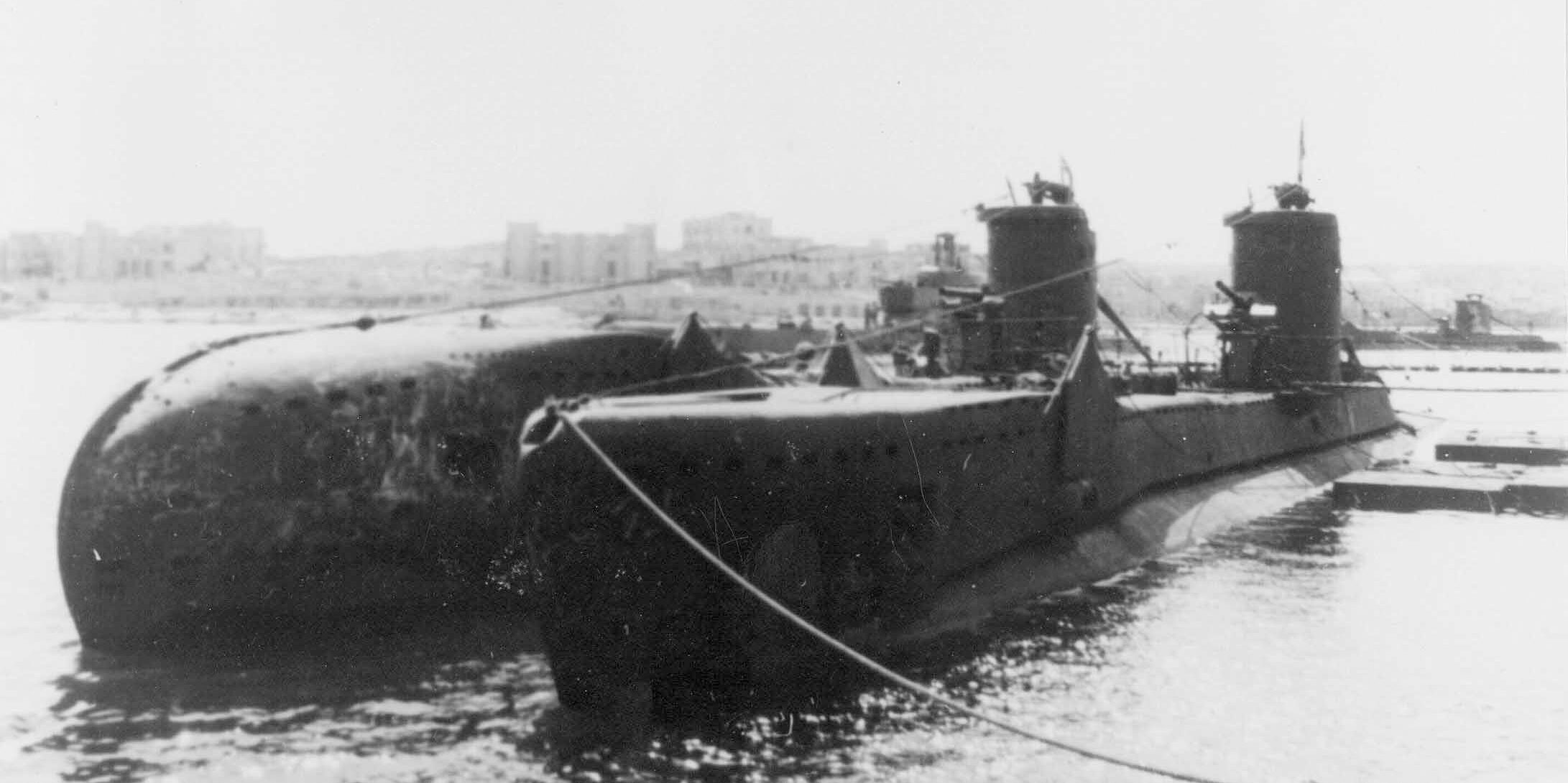

But the Luftwaffe formations were being shot to pieces by the RAF pilots. One bombing unit, Kampfgeschwader 53, had six of its Heinkels shot down and two more damaged; one badly damaged Heinkel crash-landed at the RAF airfield at West Malling. Kampfgeschwader 2 lost eight Dorniers with four more damaged. Group Captain Stanley Vincent, a veteran of World War I who was now station commander of RAF Northolt, broke up a formation of eight Dorniers by attacking them head on. The eight bombers turned and headed for France, shaken by the unexpected attack.

Spitfire and Hurricane squadrons attacked the bombers over London and harried them when they scattered and broke for the Channel. The pursuit of the enemy went on until after 4 pm, when the last of the German bombers reached the safety of France. Many of them landed with dead and wounded aboard. Some of the planes would never fly again.

But the day was not quite over. At just about 6 pm, about 20 Me-110 fighter bombers of Erprobungsgruppe 210, an elite, special-purpose unit commanded by Walter Rubensdörffer, attacked the Supermarine aircraft plant at Southampton. The pilots of the big, twin-engine German aircraft showed grit and determination, diving straight through a murderous antiaircraft barrage. They came down in fast, shallow dives in two waves of 10 planes each. After they dropped their bombs, they sped off, reformed, and disappeared.

Eyewitnesses on the ground were impressed by the flying skill of the German pilots. They had obviously been well trained and flew as a highly disciplined and coordinated team. Their flying ability was a lot more impressive than their bombing accuracy, however. None of their bombs landed anywhere near the Southampton factory.

Every one of Erpro 210’s twin-engine Messerschmitts returned to their French bases without any damage. But, in spite of their fancy flying and their unquestioned bravery, the men had not accomplished a thing. Production and delivery of Supermarine Spitfires suffered no interruption except for a few minutes when the factory workers took cover in air raid shelters.

Erpro 210’s departure for France marked the end of fighting on September 15. The battle between RAF Fighter Command and the Luftwaffe had been hard and intense, but not as intense as it had been in late August and early September, when the RAF lost 26 fighters and 13 pilots. In fact, RAF squadrons were losing 20 or more aircraft nearly every day. It was beginning to look as though the British were losing the war of attrition.

But after the actual battle had ended, the propaganda battle of September 15 began. The Luftwaffe claimed 78 RAF fighters destroyed, a number that Propaganda Minister Josef Göbbels broadcast throughout Germany and its occupied territories. Actual RAF losses that day amounted to 29 fighters.

Britain’s Ministry of Information also threw itself into high gear. The RAF officially claimed 185 German aircraft shot down on September 15. The MOI announced this number to all the news services in the British Isles and throughout the Commonwealth and also made certain that the American press received it.

As it turned out, this claim was just as inflated as the Luftwaffe’s. Postwar British records gave the total as 60 German aircraft destroyed; German sources show the Luftwaffe lost 56 airplanes, with two missing.

But in wartime, the truth is usually either overlooked or totally ignored. The number 185 sounded a lot more impressive than either 56 or 60. Newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic published the story that 185 German attackers had been shot down. Even members of the British War Cabinet were officially informed that 186 enemy aircraft had been shot down. No one ever explained where the additional German aircraft came from. The MOI’s figures did not have to be accurate, just dramatic.

Prime Minister Churchill had seen the movement of both British and German aircraft—the “shifting of the discs”—throughout the day, as well as the “continuous eastward movement of German bombers and fighters” after the day’s action had ended, from the control center at Uxbridge. When the control center’s map was clear of all aircraft, the prime minister and his party, which included Mrs. Churchill, were driven back to the PM’s residence at Chequers.

That evening, Churchill sent a message to Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, the commander of RAF Fighter Command—a message of praise about the air battle: “Aided by Czech and Polish squadrons and using only a small proportion of its total strength, the Royal Air Force cut to rags and tatters separate waves of murderous assault upon the civil population of their native homeland.”

The message was sent for propaganda purposes as much as it was to inform Air Chief Marshal Dowding. In his memoirs, Churchill gave a more reflective assessment of the battle. “We must take September 15 as the culminating date,” he wrote. “It was one of the decisive battles of the war, and, like the Battle of Waterloo, it was on a Sunday.”

In the British Isles, September 15 would become celebrated as Battle of Britain Day, acknowledging the day as the turning point of the battle and as one of the turning points of the war. But no one realized this at the time.

During the evening of September 15, the leading topic of conversation was still the possibility of a German invasion of England. In his broadcast to the United States, CBS reporter Edward R. Murrow mentioned that “much of the talk” he had heard throughout London concerned the threatened invasion.

The Germans would continue to cross the Channel in seemingly endless waves until Hitler decided that the Soviet Union would be an easier opponent than Britain and began to husband his resources for an invasion of that communist nation.

As for the 24-year-old Red Tobin, he became one of the first three members of the No. 71 “Eagle” Squadron—an all-American unit made up of pilots from the United States that was established by the RAF in September 1940, prior to America’s entry into the war. Unfortunately, he would lose his life on September 7, 1941, while tangling with German planes over Boulogne-sur-Mer in northern France.

The other two pilots who were part of the trio who first volunteered for the Eagle Squadron—Vernon “Shorty” Keough and Andrew “Andy” Mamedoff—also died.

Of the 28 Yanks who joined the Eagle Squadron, 25 would lose their lives—an 89 percent death rate. Tobin and many other Yank pilots made the supreme sacrifice in the defense of Great Britain and the cause of liberty.

Join The Conversation

Comments