By David A. Norris

Major Henry B. McClellan should have had a quiet afternoon. At dawn on June 9, 1863, Union cavalry had launched a surprise attack on Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart’s forces near Brandy Station, Virginia. Untroubled, the Confederate leader led his men out of camp to deal with the threat, assigning McClellan to remain at their headquarters on Fleetwood Hill. As the recently appointed assistant adjutant general of Stuart’s force, McClellan expected to have little more to do than coordinate and relay reports from mounted couriers. All hope for anything like a routine day vanished when McClellan turned to see several thousand Federal horsemen bearing down on Fleetwood Hill.

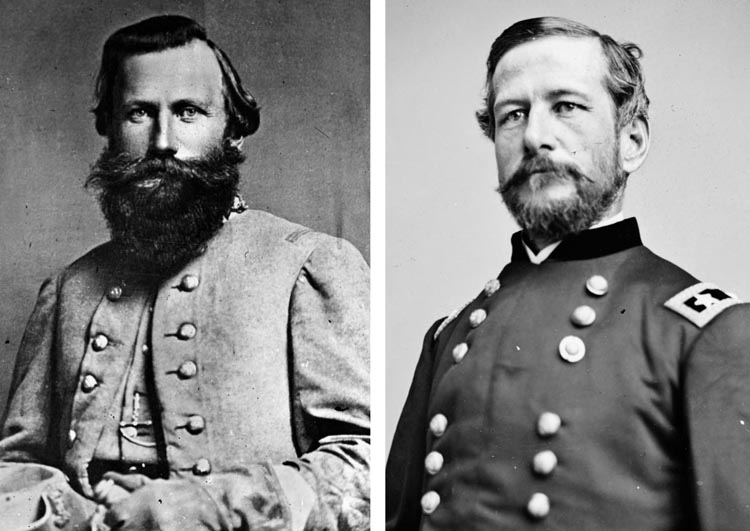

By mid-1863, Stuart was already a legendary cavalry commander. Born in Virginia in 1833, he graduated from West Point in 1854 and served on the western frontier. In 1859, Stuart took part in capturing John Brown at the arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Joining the Confederacy in 1861, Stuart thrived as a cavalry commander. He had an eccentric fondness for display, wearing a bright yellow sash, a gray cape lined with bright red, and a hat decorated with ostrich plumes. Although a bit of a dandy, Stuart could back up a reputation as a horseback hero. Twice he led his cavalry completely around the Union Army, gathering vital intelligence, tying up thousands of enemy troops, and escaping scot free.

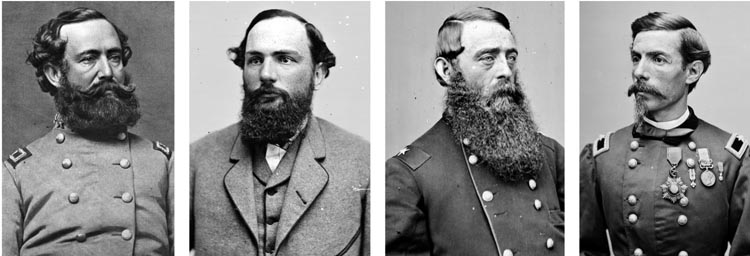

After the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, Stuart’s forces grew, with veteran troops returning from furloughs with new horses to replace those lost in earlier battles. The brigades of Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson and William E. “Grumble” Jones were added to Stuart’s command, and Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s division came back from detached duty. Also with Stuart were the brigades of W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee and Fitzhugh Lee, the son and nephew of General Robert E. Lee. Under Major Robert F. Beckham, the cavalry division’s horse artillery was also augmented, bringing it to five batteries. In June 1863 Stuart’s five brigades of cavalry numbered about 9,500 men.

The Army of Northern Virginia moved out of Fredericksburg on June 3, headed for Pennsylvania. Marching south of the Rappahannock, it would pass through Culpeper County on the way to the Shenandoah Valley into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Stuart’s cavalry was to screen the army’s movements. Early in June, Stuart and his men camped around Brandy Station, six miles east of Culpeper. The cavalry’s attention was focused not on the Yankees, but on a grand review scheduled for June 5. Confederate dignitaries, friends, and relatives of Stuart’s officers arrived by train from Richmond. Wagons and army ambulances met the trains and brought the audience to the show. Many visitors and officers attended a ball at the courthouse in Culpeper on the night of June 4.

At 8 am, Stuart and his staff rode to the site of the review, a broad rolling plain between Culpeper and Brandy Station. Trumpets sounded as Stuart rode by on a splendid horse draped with flowers. His officers, too, made a fine spectacle in new uniforms, with their hats bedecked with plumes. Thunderous salutes echoed from the batteries of the horse artillery, and the cavalry corps lined up for a mile and a half across the plain. Thousands of horses galloped in front of the review stand, their riders brandishing sabers and shouting as if they were bearing down on enemy lines in a real charge. Another review took place on June 8. Held primarily for General Lee, there were fewer dignitaries and civilians on hand. Lee enjoyed the sight, although he ordered a less strenuous program to spare the horses and men.

Stuart planned to cross the Rappahannock the next day to see what the Yankee cavalry was up to. Confederate intelligence placed the enemy camp about 12 miles from the north bank of the river. But Stuart was not the only one with plans to cross the Rappahannock. After spending the winter strengthening the cavalry, the Union Army was ready to try out the revised version of their mounted arm, now under the command of Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton.

In February, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker had consolidated the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac into a single corps under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman. Displeased with Stoneman’s efforts during the Chancellorsville campaign, Hooker fired Stoneman on May 22 and replaced him with Pleasanton, who had been a cavalry division commander. An 1844 graduate of West Point, Pleasanton had served well in the war with Mexico and later Indian campaigns. Promoted to captain in 1855, he became the senior cavalry captain following the mass resignations of Southern officers in 1861.

Dissatisfied with his status, Pleasanton constantly maneuvered for higher posts, and his self-aggrandizement irritated his subordinates. Rising to command of a cavalry brigade, he achieved considerable notice during the Antietam campaign, in part from embroidering his reports and partly from careful cultivation of news reporters. Charles Francis Adams, Jr., a captain in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry and the grandson of President John Quincy Adams, considered Pleasonton “pure and simple a newspaper humbug. You always see his name in the papers, but to us he is notorious as a bully and a toady. He does nothing save with a view to a newspaper paragraph.” Similarly, Colonel Charles Russell Lowell believed that Pleasonton’s rapid rise to promotion was due to his “systematic lying.”

Although Pleasanton was more skilled at scheming than at military tactics, he commanded a remarkable lineup of young officers. Commanding the 8th Illinois Cavalry was Colonel Elon Farnsworth. With Farnsworth’s regiment was Captain George A. Forsyth. One of Pleasonton’s aides was a first lieutenant of the 5th U.S. Cavalry named George A. Custer. Another of the general’s aides-de-camp was Captain Ulric Dahlgren, the son of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren. Captain Wesley Merritt was also an up-and-coming young officer.

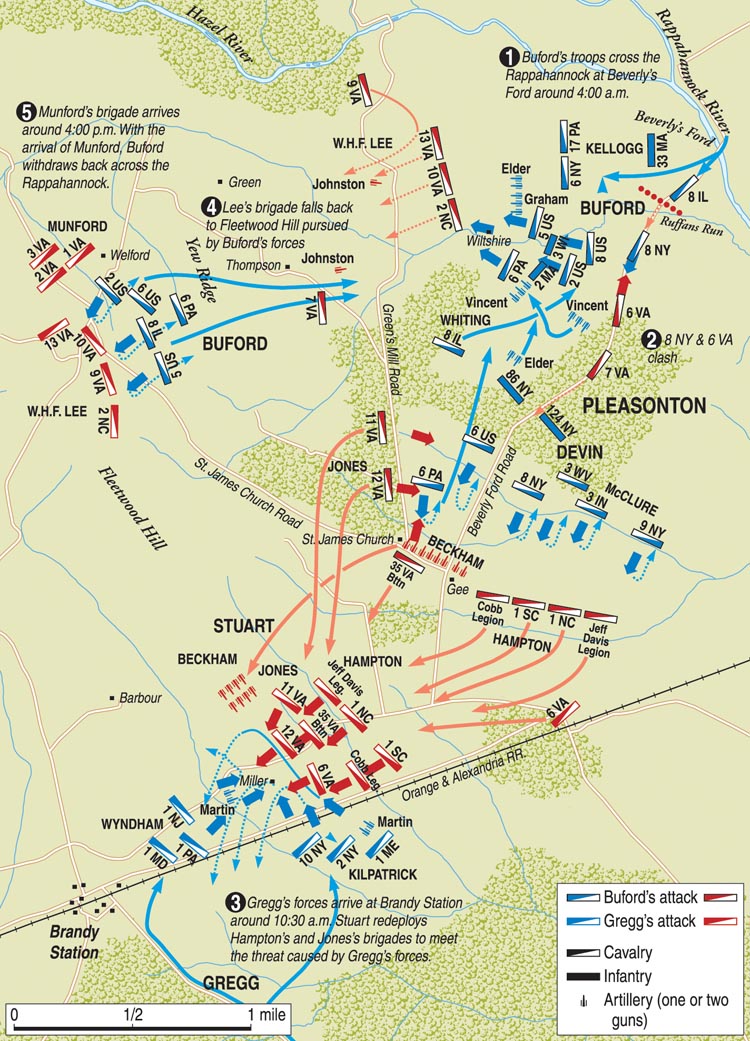

On June 7, Dahlgren brought orders to Pleasonton from Hooker to cross the river and attack Stuart. Pleasonton was instructed to “disperse and destroy the Rebel force assembled in the vicinity of Culpeper, and to destroy his trains and supplies to the utmost of your ability.” The Union force was split into two sections. Brig. Gen. John Buford, with the cavalry brigades of Colonel Benjamin F. Davis, Colonel Thomas C. Devin, and Major Charles Whiting, would cross Beverly Ford on the Rappahannock. Whiting’s command was the reserve brigade, with the regulars of the 1st, 2nd, 5th, and 6th U.S. Cavalry and three regular batteries of Captain James M. Robertson’s U.S. Horse Artillery. Whiting also had one state regiment, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry. The steadiness of the regulars was welcome, but several of the regiments’ companies were not present, being scattered on detached duty.

Brigadier General David M. Gregg would lead two more divisions with three batteries of artillery across the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford, about five miles southeast of Beverly Ford. Gregg’s own cavalry division included the brigades of Colonel Judson Kilpatrick and Colonel Sir Percy Wyndham. Also under Gregg’s command was Colonel Alfred Duffié’s division, with two brigades, those of Colonel Luigi Palma di Cesnola and Colonel John Irvin Gregg (a cousin of General Gregg). Brig. Gen. David A. Russell brought a brigade of infantry as well.

Part of Gregg’s force was the 1st Maine Cavalry, of Kilpatrick’s brigade. They received their orders at noon on June 8. The regiment rode out of camp, watching immense clouds of dust across the river that were being kicked up by Stuart’s second review. Halting for the night near Kelly’s Ford, the troopers were forbidden to cook or make coffee, lest the fires tip off the enemy to their march. After eating some cold food, the men were allowed to sleep, but “holding their horses by their bridles.” When the troopers were awakened to begin their advance long before dawn, a veteran of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry remembered the order “to horse” was whispered to his regiment.

About midnight, the 1st Maine Cavalry was awakened and told to be ready to move out at 3 am. Their early rising was for nothing. Gregg’s men were left waiting because Duffié’s brigade was led down the wrong road by their guide. They waited, “enjoying the soldiers’ prerogative of growling,” a veteran later recalled. Lack of sleep and coffee had the Maine troopers “cross enough for all practical purposes.”

In contrast with the Federal forces across the Rappahannock, the Confederates were relaxed and casual. Troopers of Jones’s brigade, who were closest to the attack route planned by Buford, turned their horses loose to graze before settling in to sleep on the night of June 8-9. The gunners of the horse artillery, camped near Jones, also turned their horses loose for the night.

Buford’s force reached the Confederates long before the rest of the Federals. Fog hovered over the water as his bluecoats splashed across Beverly Ford at 4:30 am. Water poured over a dam just upstream of the ford, helping muffle the noise of the crossing. The water was about stirrup deep. Strong currents knocked some of the 124th New York Infantry off their feet, soaking them and their ammunition. As the cavalrymen rode out of the ford and onto the bank, a staff officer quietly ordered, “Draw sabers.” Buford quickly swept through the pickets at the ford, who were a single company of the 6th Virginia Cavalry. The only route through the low ground was the Beverly Ford Road. Bordered by deep ditches, the road squeezed the Federal horsemen into a column of fours.

Jones’s brigade was camped roughly two miles down the Beverly Ford Road. The 6th Virginia Cavalry bedded down in a grove of oaks near a brick home known as the Gee House, on the south side of the road. Across the road at St. James’ Church was the rest of the brigade. Awakened from their sleep by gunshots coming from Beverly Ford, some of Jones’s men dashed to the fighting on foot. Others pitched into Buford’s advance half-dressed and riding their horses bareback.

Major Cabell E. Flournoy and about 100 men from the 6th Virginia Cavalry attacked the lead Union brigade, under Colonel Benjamin “Grimes” Davis. A former dragoon officer on the frontier, Davis was born in Alabama but gave his loyalty to the Union. Flournoy’s force couldn’t stop Davis, but did slow him down before they turned and rode back toward their camp. One of Flournoy’s officers, Lieutenant R.O. Allen, spotted Davis leading Union soldiers down the road. Spurring his horse, Allen rode toward the surprised enemy horsemen until he was nearly upon the colonel. The Union commander hacked at Allen with his saber, but the Virginian ducked and fired his pistol. Davis died instantly from a bullet through his brain. Davis’s men believed that their commander was avenged moments later when a Union officer killed a Confederate soldier with a saber stroke that nearly cut the man’s skull in two. But Allen had gotten away, and the man killed was a Sergeant John Stone, of Allen’s regiment.

Soon after Davis fell, the commander of the 8th Illinois Cavalry, Major Alpheus Clark, was mortally wounded. Captain George A. Forsyth took command for a few minutes, but he too fell, shot in the thigh. He was carried back to the rear by several men. Confident of success, Forsyth’s men heard him wish out loud that he could have been hit at sunset instead of sunrise on this day.

Davis’s death and the sharp reaction of Jones’s brigade halted Buford’s advance. There was a brief delay while they stopped a few hundred yards from where Beckham’s gunners were trying to catch their horses and drag their guns out of reach. While the guns were withdrawn to the Gee House and St. James’ Church, Captain James F. Hart kept two guns to open fire on Federals.

As Captain James F. Hart’s guns went into action, the 7th Virginia Cavalry reached the scene. They charged into the Union horsemen but were thrown back and reeled behind Hart’s guns. Left to themselves, the gun crews took turns covering each other with canister fire as the others drew back until they reached the rest of Beckham’s horse artillery. They saved all of their guns, and the only real loss was Beckham’s desk, which fell out of a wagon during the confusion. It was just about dawn when Hart’s two wayward guns were safe, and all 16 of Beckham’s guns roared at once against the Federal cavalry.

Wade Hampton heard the firing at about 6 am. Reporting to Stuart, Hampton was ordered to support Jones. One of Hampton’s regiments, Colonel Matthew C. Butler’s 2nd South Carolina, was sent to guard Brandy Station and the approaches to Kelly’s Ford. Hampton was unable to find another of his regiments, the 1st South Carolina Cavalry. Stuart had bypassed Hampton and ordered the regiment off without telling him.

Jones fell in to the left of Beckham’s artillery. To their right, Hampton’s remaining three regiments arrived to take up positions. Against them, Pleasonton sent two partial regiments, the 6th Pennsylvania and the 6th U.S. Cavalry. Earlier in the war, the Pennsylvanians were known as Rush’s Lancers because they were armed with nine-foot-long lances. By mid-1863, the lances decorated with scarlet streamers had been put aside in favor of more practical sabers and pistols.

Dahlgren joined the Pennsylvanians as they charged. Bursting from the cover of some woods, they came to 800 yards of open ground, behind which were Beckham’s guns and the carbines of Jones and Hampton. The Confederate line was concave. Charging straight into the center, canister sprayed into them from the horse artillery, and carbine fire poured into them from both flanks. Despite the heavy fire, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry kept an unwavering course toward the guns. The bluecoats burst through the artillery line, but after riding between the guns they were stopped and driven back by Confederate small arms fire.

Riding next to regimental commander Major Robert Morris, Dahlgren saw the major fall when his horse was hit. Injured, Morris was captured that day and later died in Libby Prison. Dahlgren’s horse was also hit and threw the captain to the ground. Staggering to his feet, Dahlgren saw that the regiment was reeling back under the hot fire. He was within moments of being surrounded and taken. The admiral’s son managed to get his horse back up and escape, although a blow from the back of a saber nearly knocked him from the saddle again. From that charge, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry suffered 108 casualties, the highest losses of any Union regiment at Brandy Station.

While Jones and Hampton held on, Buford anchored his right on the Hazel River, a tributary that flowed into the Rappahannock near Beverly Ford. Rooney Lee’s brigade reached the fighting and settled on the left of Jones’s troops, behind a stone wall in front of a rise called Yew Ridge. Stuart sent Beverly Robertson with his brigade, along with Hampton’s 1st South Carolina Cavalry, to cover Kelly’s Ford.

By late morning, Buford had succeeded only in driving the Confederates from the stone wall. Bogged down by stubborn Confederate resistance, he was unable to advance to meet Gregg at Brandy Station. He didn’t even have any idea of the location of the rest of the Federal forces until the Confederates suddenly withdrew from the stubbornly held lines in front of him. But Gregg had at last reached Brandy Station and the Confederates were in serious trouble.

Because Gregg’s forces lost a lot of time early that morning waiting for Duffiè’s lost brigades, they had a late start. Then, although Kelly’s Ford was unguarded, they found that the road they intended to take to Brandy Station was blocked by Robertson’s brigade. As the Federals had recently held the area, they had good knowledge of the local roads and it was easy to evade Robertson by taking another route. Fortunately for the Federals, Robertson held rigidly to his orders. Assigned to block the road from Kelly’s Ford, he did just that and stayed in place rather than pursue the enemy. Robertson sent couriers to warn Stuart, but even this minimal effort was not done quickly enough. For the rest of the battle, Robertson’s sabers were idle, depriving the Confederates of badly needed manpower.

Duffiè had orders to separate from Gregg and head for Stevensburg, five miles south of Brandy Station. At the expense of some weakening of the Federal force, Duffiè would protect the rest of the bluecoats from a flanking attack from any of Lee’s infantry coming from the south or west. Gregg got to Brandy Station about 11:30, hours behind schedule. But, once he got there, he was in the Confederate rear and within one mile of Fleetwood Hill. Robertson’s inaction meant that no one knew the Federals were coming.

His attention focused on Buford, Stuart had almost abandoned Fleetwood Hill. Now, the way was open for Gregg to take it, which offered an ideal position on the battlefield. Unlike the wooded land closer to Beverly’s Ford, Fleetwood Hill overlooked mostly open and gently rolling terrain. The elevation of the hill would give a commanding position to whoever got their artillery there first. All around, there were broad open spaces for cavalry to maneuver in the open. Most of the fences and hedges had been destroyed when the armies passed through during the Second Manassas campaign in late summer 1862.

Back at headquarters, Major Henry McClellan found himself nearly alone on the key objective of the battlefield. Earlier, McClellan had sent the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry from Brandy Station to cover the approaches from Stevensburg. Like Stuart, McClellan had felt that the hill was quite safe. He was not shocked so much as baffled when one of Robertson’s couriers galloped up with warnings that a big Federal force was headed toward Fleetwood Hill. At first, the courier’s report was just unbelievable. Surely Robertson would not have let the Federals simply slip by him. McClellan sent Robertson’s rider back to make sure that “he had not mistaken some of our troops for the enemy.”

Less than five minutes passed before the courier was back. Now, he told McClellan, you can see for yourself. Sure enough, the new forces were not Confederates, but thousands of blue-coated Federal troopers engulfing the depot at Brandy Station. Fleetwood Hill, now already within cannon range of the enemy, looked doomed to a quick capture. If the Federals took to the summit, they could only be driven away at a terrible cost.

McClellan was playing his last cards. He had sent his one remaining courier and now there were no Confederates with him on Fleetwood Hill except for the crew of a single 6-pounder howitzer. That lone gun of Captain Robert Preston Chew’s battery was commanded by Lieutenant John Wright “Tuck” Carter. During the morning, Carter had shot away almost all of his ammunition and his gun was ordered withdrawn. This gun was supplied only by a nearly empty caisson, and Carter had already found out that most of his remaining shells were defective.

But Carter’s gun turned out to be just barely enough to hold the hill for a few minutes. When the 6-pounder gun opened fire, even its defective ammunition proved dangerous enough to make the Federals hesitate. Where there was one gun, there could soon be more. Buford was nowhere to be seen, and Gregg had not established contact with him. Gregg called a halt and ordered three of his rifled guns into action before sending in his cavalry.

As Carter’s gun fired away its remaining shots, Windham’s brigade swept up the western side of Fleetwood Hill. They were led by Wyndham, one of the war’s most colorful characters. Born on a ship to a British military couple bound for India, Wyndham had a strange military career. Not following his father into the British service, he first tried the French Navy, and then he became an Austrian cavalry officer. Resigning from the emperor’s service, he joined the Italian forces fighting for their independence under Garibaldi. Sir Percy’s knighthood was granted by King Victor Emanuel of Italy. Coming to America, he sided with the Union and his experience and military bearing helped him rise to brigade commander.

Like Stuart, Wyndham had a fondness for military pomp. He loved fancy uniforms and sported one of the war’s most spectacular moustaches. Lieutenant Samuel Harris of the 5th Michigan Cavalry served under the flashy officer, who he considered a “bag of wind.” Under pressure, Wyndham’s bombast was matched by dash and courage. He led his riders to the crest of the hill, where they slammed into Jones’s men, the first to reach the field after McClellan’s desperate appeals.

Just as McClellan didn’t believe the courier warning him of Gregg’s approach, Stuart was annoyed and skeptical about McClellan’s call for help. Turning to Captain James F. Hart, the commander said, “Ride back there and see that all that foolishness is about.” When the next courier from McClellan arrived, he was accompanied by a plain warning: the booming of cannon from the direction of Fleetwood Hill. Some of Jones’s cavalry was peeled away and sent flying to defend the hill.

The vanguard of Colonel A.W. Harmon’s 12th Virginia Cavalry reached the hill just as Carter fired his last shot. Close behind them came the 6th Virginia Cavalry and the 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry. They found Wyndham’s troops charging up the western slope of the hill. Already worn down from a long morning of fighting, the Virginians were widely scattered in their headlong rush to the hill. Private John Newton Opie of the 6th recalled, “So great was the danger, that we were marched for two miles in a sweeping gallop; consequently, when we reached the enemy, our horses were blown and our ranks completely disordered.” Hitting the Union attackers piecemeal, the Virginians were thrown back.

Stuart reached the hill and it took only a glance for him to see that more men were needed there. He summoned all of Jones’s and Hampton’s brigades and the artillery from the Beverly Ford Road. Hampton was already withdrawing his men to avoid being trapped between two Union forces. Some of Beckham’s pieces had been dispatched to aid Robertson and Butler. Damaged by the shock of recoil, three guns were out of action. Beckham left three pieces to support Rooney Lee and followed Hampton with the rest.

For the moment, the Confederate cavalry was thrown back, and Sir Percy Wyndham led the 1st New Jersey Cavalry in charging two Confederate batteries from their right flank. The batteries, under Captains Hart and William M. McGregor, had just reached Fleetwood Hill. With no support at all, the gunners fought off the enemy cavalry with pistols, trail handspikes, or whatever came to hand. One gunner knocked a horseman from the saddle with his sponge staff.

More Confederate cavalry reached the fighting, and the New Jersey horsemen were driven back off the hill. Many were left behind wounded or dead. Their commander, Lt. Col. Virgil Brodrick, was found with a saber through his body. Near Brodrick was a dead Confederate soldier, impaled on the lieutenant colonel’s saber. Taking over the regiment, Major John Shellmire also fell with a fatal wound. Wyndham, badly wounded in the leg, withdrew with the remnants of the 1st New Jersey with 150 prisoners in tow.

On a knoll near the bottom of Fleetwood Hill were three rifled Union guns from Captain Joseph W. Martin’s 6th New York Independent Battery. Martin, following orders from Wyndham, brought his two-gun section to this advanced position. While Martin was in transit, three more couriers arrived from Wyndham urging him to hurry up. He joined Lieutenant M.P. Clark, who was already on the knoll with one gun. Clark’s other gun had burst earlier in the battle.

Twice Martin called for support. Although assured that help was coming, the only cavalry approaching his isolated position were all Confederates. Led by Lt. Col. Elijah “Lige” White, the 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry swept down upon the battery. Originally raised as partisan rangers, White’s unit grew into a small but formidable battalion of regulars. Later they came to be called White’s Comanches for their headlong bravery. Martin’s gunners fired canister as quickly as they could. They slowed White’s riders, but three guns could not fire fast enough to fend them off for long. After a few blasts of canister, White’s troopers and their sabers and pistols cut their way amid the New York guns and squelched their fire.

Only half a dozen of the 36 Union gunners avoided being wounded or captured. Private James Ingram stated that his crew tried to save their gun, “but we had only two horses left, and one of them was wounded.” Leaving their guns disabled by bursting, wedging, and spiking and destroying all of their fuses, the gunners scattered. Most were either wounded or captured. Ingram and one comrade ran but made it only about 100 yards before they were captured. They escaped briefly but were captured again and this time sent to Richmond. Like most of the battery’s captured enlisted men, they were exchanged for parole a few days later.

After the hard fighting to take the guns, White’s Confederates lost them to two companies of the 1st Maryland Cavalry. Yet the Marylanders found themselves in the same fix as the New York gunners, unable to move the guns for lack of horses. The guns changed owners twice before ending up for good in Confederate hands.

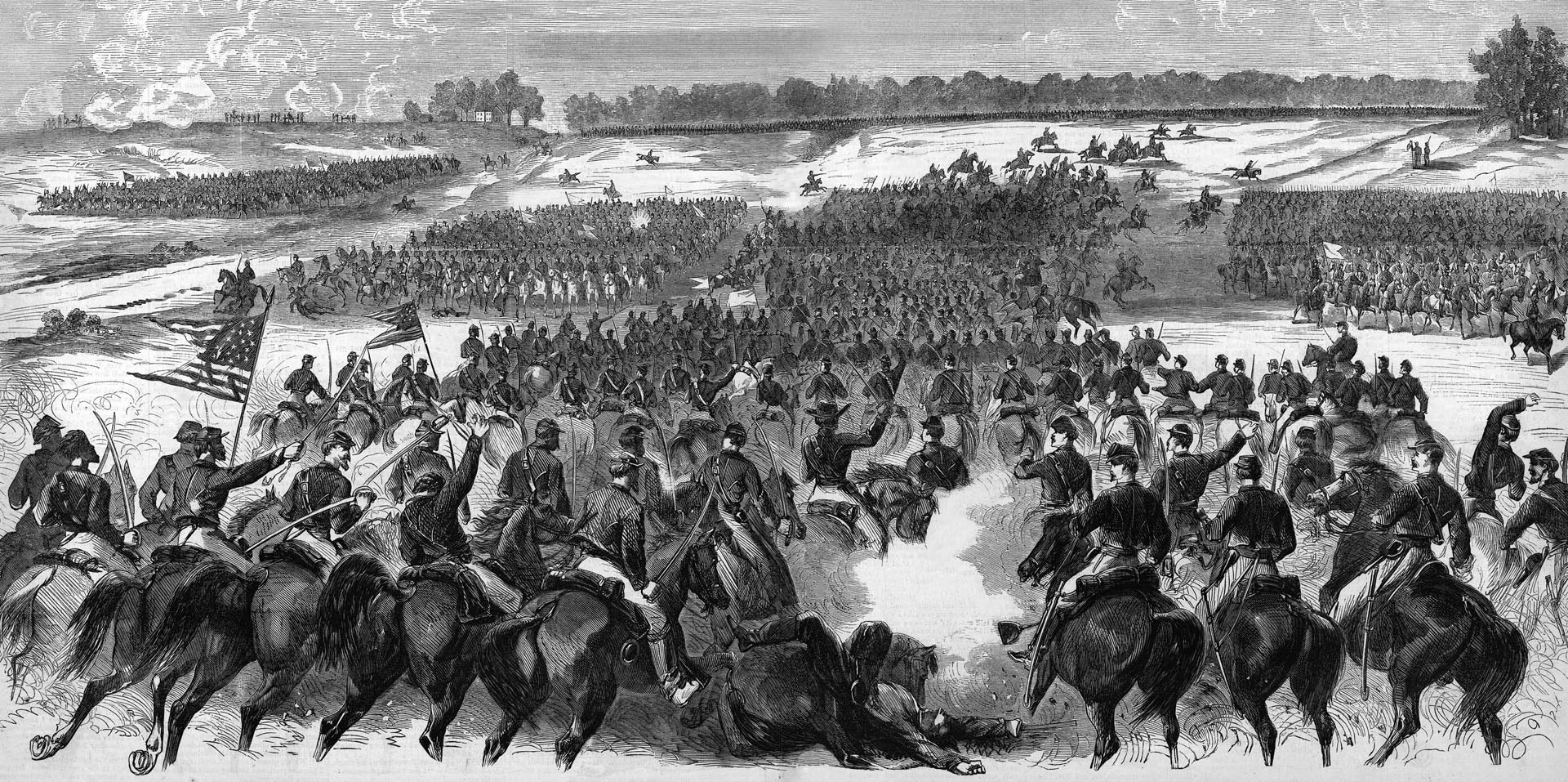

There was no sign of Duffié yet. Gregg threw Kilpatrick’s brigade into the growing melee on the hill, while Stuart fed in all the men he could spare from keeping Buford in place. For the rest of the afternoon, Union and Confederate regiments took turns holding the hill. By 1863, the deadly artillery of the age and the long ranges attained by the rifled musket firing a Minie bullet were changing cavalry tactics. Cavalry horses brought men quickly to where they were needed, but the horsemen usually dismounted and fought on foot. At Brandy Station, there was no time for dismounting and digging in on Fleetwood Hill, and often no time to reload firearms. The massive cavalry charges and clashing saber duels of the afternoon are what are remembered most about the battle.

The sheer number of horses on the field stirred massive amounts of dust from the dry ground. A newspaper man wrote that “the choking dust was so thick that we could not tell ‘t’other from which.’ Horses, wild beyond the control of their riders, were charging away through the lines of the enemy and back again.” The newsman continued, “I have only mentioned what passed under my own eye and in the dust one man could not see far.” Visibility was so limited that officers could not always keep regiments or even companies together. Soldiers found themselves cut off among enemy troops and fought in squadrons, scattered small groups, or sometimes even alone.

After interfering with two of Hampton’s regiments that morning, Stuart further annoyed the South Carolinian with other orders that undercut him on the field. Some of Stuart’s horse artillery, which rushed to the top of the hill, took aim and bombarded his 1st North Carolina Cavalry. When they halted to correct their mistake, some Union cavalry escaped into the woods. To follow up what seemed to be a fine opportunity, Hampton ordered two of his regiments after them, but their officers told him that they had direct orders from Stuart to remain in place and defend the hill.

Although most Confederates had been pulled back from the Beverly Ford Road, Rooney Lee stayed in place to keep Buford in check during the afternoon. He was joined by Colonel Thomas T. Munford, leading the brigade of Fitzhugh Lee in place of its commander, who was on the sick list.

Duffiè and his 1,200 men, assigned to ride to Stevensburg, were too far from the main battle to have much direct impact. Butler’s 2nd South Carolina Cavalry, numbering about 220 men and separated into detachments, fought to slow their advance to Fleetwood Hill. Leading three dozen mounted men in a charge against part of Duffié’s force, Wade Hampton’s brother, Lt. Col. Frank Hampton, crossed sabers with a bluecoat rider. While fighting the horseman, Frank Hampton took a saber slash to the head, and another Federal fatally shot him.

Arriving on the scene, the 4th Virginia Cavalry were surprised by Duffié’s fire and broke. After the regiment was scattered, the Union troopers again fired on the 2nd South Carolina. One bursting shell cut off Butler’s foot, tore through his horse and then through the horse of Stuart’s staff officer, Captain William Downs Fairley, slicing off Fairley’s leg at the knee. Fairley, still conscious as he was being carried away for treatment, pointed to the severed piece of his leg and asked for it. Holding the remnant of his leg to him, he said, “It is an old friend, gentlemen, and I do not wish to part with it.” Butler survived a long recovery and returned to service, but Fairly died later that day.

This sideshow, remote from the main battlefield, extorted a heavy cost in top-notch Confederate officers. But their stand kept Duffié away from Fleetwood Hill and potentially saved the day for the defenders. Gregg finally made contact with Buford’s left, but he was gradually driven from Fleetwood Hill back to the railroad. Buford had not been able to decisively break through the line of Rooney Lee. Late in the day, Lee was seriously wounded in the leg near the end of the battle. Lee would be sent to recover at the Hanover County home of Colonel William Carter Wickham, one of Stuart’s officers and a relative of Lee’s wife. On June 26, Union cavalry raiders under Colonel Samuel Spear captured Lee, carried him out on a mattress, and took him away in a wagon. He remained a Union prisoner until his exchange at City Point on March 14, 1864.

At 5 pm, Pleasonton ordered a withdrawal because he heard that Confederate reinforcements were coming. Buford’s forces returned to Beverly Ford to cross the Rappahannock, and about the same time, Duffié finally reached Brandy Station. Gregg and Duffié withdrew by way of Rappahannock Ford (also called Rappahannock Station Ford or Cow’s Ford), near the Orange & Alexandria Railroad bridge between Beverly and Kelly’s Fords. Although the Confederates threw some shells after the Federals, Stuart declined to chase them.

Brandy Station is generally considered the greatest cavalry battle ever fought in North America. About 20,500 soldiers—some 9,500 Confederate cavalry and 11,000 Union troops including 3,000 infantry—took part in the battle. Union casualties numbered 866, including 10 officers and 71 enlisted men killed. Confederate losses were 523.

Stuart considered Brandy Station a Confederate victory. Admittedly, the Southerners were caught off guard but recovered from their surprise and held the field at the end of battle. So adamant was Stuart on the latter point that he intended to set his headquarters camp once again on Fleetwood Hill. But W.W. Blackford noted that after the battle the once-idyllic headquarters site was strewn with dead horses and swarming with bluebottle flies. Stuart reluctantly ordered camp set up elsewhere.

Stuart’s claims of victory were, by a narrow definition, true enough. Most Confederates, though, agreed with the Richmond Examinerthat Brandy Station was “a victory over which few will exult.” Recovering from a surprise attack and fighting well was one thing, but the thought arose that Pleasonton should not have been able to make a surprise attack in the first place. To the Confederate public, Stuart had been showing off for his grand reviews and wearing out his horses and men for no purpose. Instead of detecting the enemy movement ahead of time, the cavalry was caught napping by the very Union horsemen they had embarrassed and outclassed many times.

As far as the North was concerned, the Battle of Brandy Station was something to celebrate. For the first time, Union cavalry had held its own in a major clash with Stuart’s force. Deftly adjusting to the flaws and unexpected changes in their battle plans, they were more than once on the verge of a significant victory. Henry B. McClellan said of Gregg’s attack, “Modern warfare cannot furnish an instance of a field more closely, more valiantly, contested.” The earlier embarrassments of the Union cavalry were behind them now. After Brandy Station, they felt themselves the equals of Stuart’s legendary horsemen. By 1865, they would be a major factor in granting victory to the Army of the Potomac. As McClellan tersely summed up Brandy Station, “It made the Federal cavalry.”

When taken into consideration the relative positions of the two armies in terms of resources and strategic positions just a month later, the Examiner was quite correct. Many more “victories” like Brandy Station for the south and the war would have been over sooner than it eventually was.