By Simon Rees

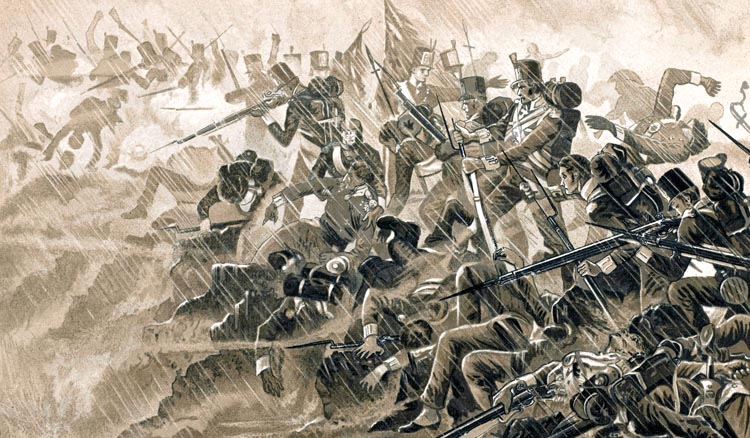

Amid gun smoke and squalls of rain, the men of 1st Battalion, 3rd Foot, known as the Buffs, were firing their weapons and listening for further orders. Others tended to wounds, while still more were dying or already dead. The unit had run into a maelstrom of cannon shot and musket balls, exchanged volleys, and then joined a brigade-wide charge: stabbing, clubbing, and clawing their way forward until their opponents briefly wavered. However, the French held firm and had soon forced the British to retire.

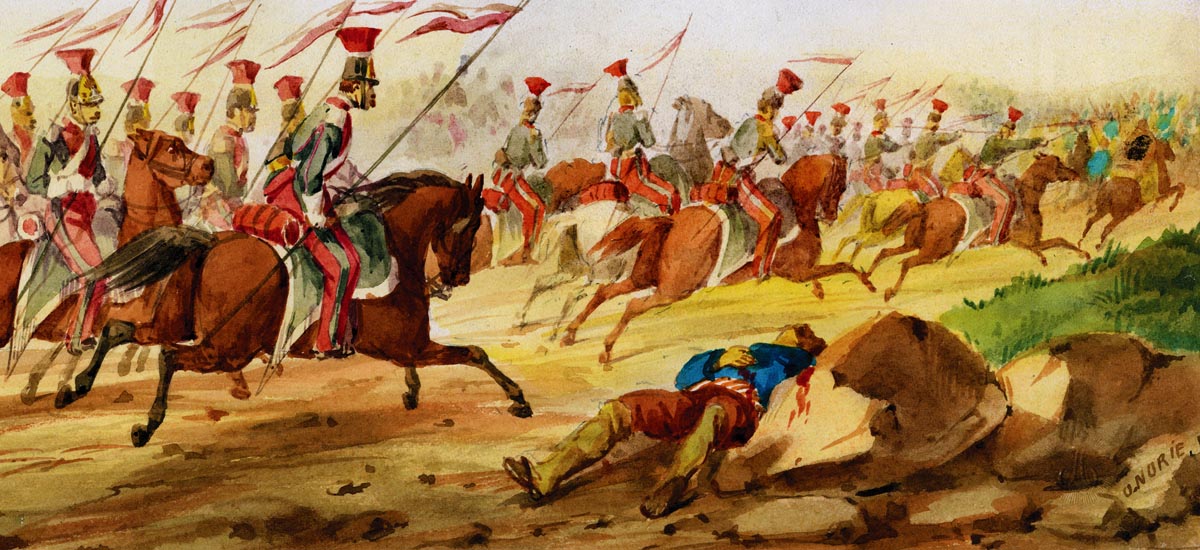

Suddenly, the Buffs’ right-hand companies were ordered to wheel around as an enemy cavalry formation had been spotted approaching. But many of the horsemen carried lances and wore uniforms with yellow facings; shouts went up that they must be Spanish allies, the relief of this assumption turning to terror when the cavalry accelerated into a charge. Within moments, hundreds of Polish lancers and supporting French hussars were tearing a bloody path through the beleaguered infantry, seemingly unstoppable in their fury.

On March 10, 1811, the Spanish fortress town of Badajoz surrendered to Marshal Jean Soult, its capture depriving the British, Portuguese, and Spanish alliance of a vital defensive bastion, one that dominated a nexus of roads in the border region of Extremadura, Spain. The commander of the Anglo-Portuguese forces, Arthur Wellesley, Viscount Wellington, urgently needed to retake Badajoz, but his immediate focus was on harrying Marshal Andre Masséna’s retreating army out of Portugal. So Wellington decided his southern wing, then under the control of Marshal William Beresford, would have to complete the job in his absence.

Physically imposing and blind in the left eye because of an early hunting accident, Beresford’s career up to that point had been steady and commendable, despite having to surrender Buenos Aires during the botched River Plate campaigns of 1806-1807. Escaping in 1807, he was appointed commander of Portugal’s strategic Madeira archipelago for several months before joining Lt. Gen. John Moore’s ill-starred 1808-1809 expedition in northern Spain. Seconded to the Portuguese Army soon afterward, he was made a marshal and helped overhaul the country’s dysfunctional army. Beresford also led a sizable flanking column during Soult’s retreat from Oporto in 1809 but had yet to take an army into battle.

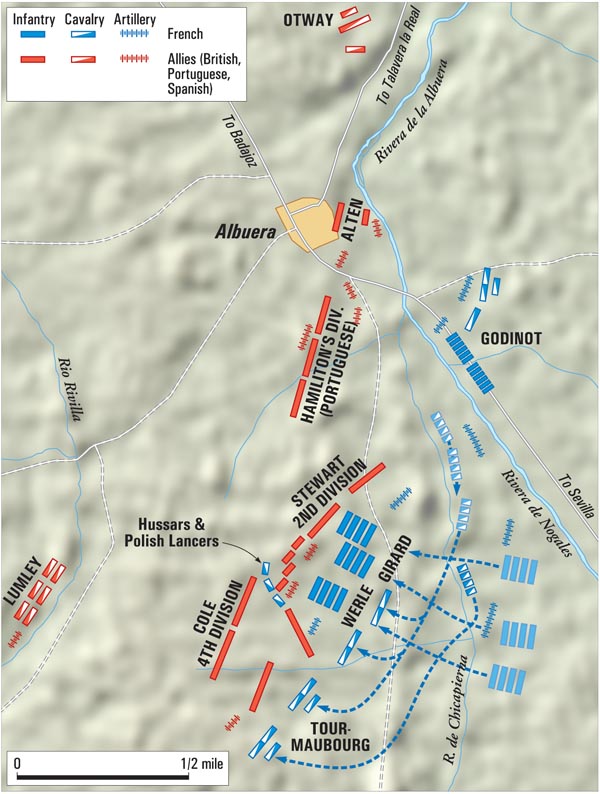

He started the campaign by concentrating 20,000 men at Portalegre, in south-central Portugal, the roster including Maj. Gen. William Stewart’s 2nd Division, Maj. Gen. Lowry Cole’s 4th Division, and several important Portuguese formations, such as Maj. Gen. John Hamilton’s division, Brig. Gen. Richard Collins’ independent brigade, and Colonel Loftus Otway’s cavalry brigade. British cavalry included Colonel George de Grey’s heavy brigade and the independent 13th Light Dragoons. In addition, there were two Portuguese and two King’s German Legion (KGL) batteries. Opposing the Allies were approximately 11,000 men from Soult’s V Corps that had been left to consolidate French gains after the marshal returned south.

The first clash occurred on March 25, just east of Campo Maior, with the 13th Light Dragoons besting several enemy squadrons and, supported by Portuguese units, decimating an enemy baggage and artillery train on the outskirts of Badajoz. Approximately 1,200 French infantry retreating from Campo Maior were left dangerously exposed, but Beresford, who erroneously had been told the 13th’s men had been taken prisoner, decided to shadow this formation and then retire. The Allies suffered 170 casualties, while the French lost upward of 400 men. The 13th’s commander, Lt. Col. Michael Head, was unfairly chastised on his return, while events that day also put Beresford at loggerheads with his newly arrived cavalry commander, Brig. Gen. Robert Long.

Despite Beresford’s awkward start, as well as a diversion in the form of an April 7 surprise raid in which two officers and 52 men from 13th Light Dragoons were captured, he made excellent progress in pushing the enemy back and isolating Badajoz. In addition, the 13th Light Dragoons had their revenge by participating in a fierce cavalry skirmish at Los Santos on April 16, with the Allies inflicting numerous casualties and capturing 150 men for almost no loss. However, Beresford remained unhappy with Long’s overall performance. Other notable efforts included the capture of Olivenza, taking 400 prisoners, and a bid to entrap General Jean-Pierre Maransin’s brigade, a move that failed only because the enemy received a last-minute warning and slipped the net.

Approximately 3,400 Spanish troops under General Francisco Ballasteros then linked up with Anglo-Portuguese forces. Meanwhile, General Joaquin Blake, a commander of Irish lineage, was marching toward Beresford with a force of several thousand after being transported from Cadiz to the mouth of the River Guadiana in mid-April. His army included two divisions commanded by General Jose Zayas and General Jose Lardizabal and it would later incorporate Ballasteros’s men. In addition, General Francisco Castanos, who already was in Beresford’s vicinity, would place 1,800 infantry and 300 cavalry at Blake’s disposal during the battle.

Many British veterans argued the Spanish were lions led by donkeys, which was an unfair assessment as there were plenty of decent, brave leaders trying to implement reform. For example, Zayas had written a manual on military order and initiated a training regimen among several battalions that would soon pay dividends. Unfortunately, too many substandard commanders remained in positions of authority for political reasons, while the Spanish soldier’s rations were meager, his pay atrocious, and his weaponry of variable quality. Uniforms were a mixture of prewar stock and locally produced or British-supplied clothing. Importantly, given the events to come, a number of Spanish cavalry units wore yellow coats or had uniforms with prominent yellow facings and finishes, while a smattering of regular and irregular cavalry units also carried lances.

Major General Charles Alten’s KGL brigade of approximately 1,100 men reached the theater on April 18, while Wellington arrived not long afterward on a quick visit to assist and guide Beresford. The pair scouted Badajoz and its environs on April 22, avoiding a sharp skirmish between accompanying KGL units and men from the French garrison. Detailed instructions on how to progress were written up the following day. Wellington chose the gutted and uninhabited village of Albuera situated 16 miles southeast of Badajoz as a primary location to oppose Soult if he tried to relieve the fortress town. Wellington returned north on April 25 and Badajoz was besieged in earnest by May 8.

Soult decided to mount a relief as the Allies predicted. His army comprised several major formations, including V Corps’ 1st Division of approximately 4,250 infantrymen and its 2nd Division of 4,150 men. General Jean-Baptiste Girard would head V Corps and take 1st Division into the fight, while General Joseph Pepin commanded 2nd Division as its usual leader, General Honore Gazan, was appointed Soult’s acting chief of staff. General François Werlé controlled an independent and over-strength infantry brigade of 5,600 men and General Nicolas Godinot a brigade of almost 4,000. There were also approximately 4,000 cavalry and between 35 and 40 cannons. In total, the French would field 24,000 men.

The bulk of Soult’s army was underway by May 9, linking up with V Corps at Fuente Cantos on May 13 and reaching Santa Marta by May 15, putting the French near Albuera and within striking distance of Badajoz. On May 12 Beresford received intelligence on Soult’s rapid advance and sensibly chose to raise the siege, despite having taken more than 400 casualties for limited gains. Stewart’s 2nd Division, Hamilton’s division, and some of his artillery were sent to Valverde, while other units were ordered to move nearer Albuera or fall back on the village when pressed. Cole’s 4th Division and Castanos’s men stayed at Badajoz, destroying supplies that could not be transported and covering the siege guns, which would soon be dragged back to the Portuguese fortress of Elvas. They would start marching for Albuera in the early hours of May 16.

Beresford, Blake, and Castanos held a council of war at Valverde on the afternoon of May 13, with Beresford arguing for a withdrawal on Elvas that would force Soult to put the River Guadiana at his back. Blake was angered by this, stressing that his men would begin to desert upon entering Portugal and that he was determined to fight on Spanish soil. Beresford could ill afford to call the Spanish commander’s bluff, so it was agreed the Allies would fight at Albuera as originally intended. Beresford would have overall control and Blake promised to march almost 12,600 men from Almendral to the battlefield, just a short distance away, by 12 pmon May 15. In total, the Allies would field 20,800 Anglo-Portuguese and 14,500 Spanish troops, plus 40 cannons.

Albuera lies close to its namesake river, with a series of gentle ridges to its west. This feature runs for several miles along a north-south axis that then kinks southwest, with two hills separated by a shallow valley located at this juncture. It offered an alternative route for any would-be attacker, although the Allies were convinced Soult was going to advance directly on Albuera. The Spanish, considered a weak link by Beresford, were made responsible for defending positions south of the village and north of the shallow valley, the Allied center-right and right, because it was where the fighting was expected to be thinnest.

The Allies made several important errors on May 15, particularly the failure to contest territory south of where the Albuera River splits into the Nogales stream, which flows southeast, and the Chicapierna stream, which heads southwest. The land between both broadens out and rises to some height, the peaks and rear slopes wooded at that time and offering a superb screen to mask any move west, particularly toward the shallow valley. Allied cavalry hastily withdrew through this location to cover the terrain on which Blake was meant to deploy. Long and his supporters later argued he had been instructed by a staff officer to make this move and that Beresford should have rushed infantry onto or near the position, one that was unsuitable for horsemen anyway.

A resolution between the two men was imminent as Long had already requested his replacement. Ostensibly, this was to ensure the correct chain of command as someone with a superior rank was needed to assume control of Spanish cavalry formations, although both undoubtedly wanted their unhappy partnership brought to an end. Maj. Gen. William Lumley, a brigade commander in 2nd Division, was selected and proved to be a relatively sound choice as he had originally been a cavalry officer. The handover would occur during the fighting, a decision later condemned by Long as unusual and an affront to his honor.

Long’s cavalry had reached the area at 2 pm, which was roughly the same time other Allied units were arriving in force. Otway’s cavalry was positioned north of Albuera and Hamilton’s division was placed to the northwest, with Collins’ brigade formed to their rear. Stewart’s 2nd Division deployed just west of the village and comprised three brigades under the respective commands of Lt. Col. John Colborne, Maj. Gen. Daniel Hoghton, and Lt. Col. Alexander Abercromby (Lumley’s acting replacement). Stewart also had 140 riflemen from the 5/60th attached. Alten’s KGL Brigade was positioned in and around Albuera to act as an early breakwater on any French advance, with cannons in support. Although these moves went comparatively smoothly, concern started to mount over Blake’s absence.

Rather than reaching the battlefield around 12 pm, the Spanish commander’s first units arrived late in the evening with his last formations and stragglers recorded at approximately 3 pm. Worse still, Blake deployed his men on the forward slopes, an elementary mistake his staff began to correct in the early hours, ordering units behind the crests to conceal their true strength and offer rudimentary protection. Back at Badajoz, Cole’s 4th Division and Castanos’s men, who were under the command of General Carlos de Espana for the battle’s duration, were getting underway. Espana would join Blake, while Cole moved behind 2nd Division as planned, with both formations arriving shortly before the battle started.

Cole was missing most of Lt. Col. James Kemmis’s brigade, which had been stranded on the north bank of the Guadiana due to a flash flood. It was forced to make a lengthy detour and would arrive after the fighting, although three of its light companies had crossed beforehand and marched with the division. Beresford was not overly concerned by this; he was more frustrated at the absence of Brig. Gen. George Madden and his Portuguese cavalry brigade, last seen scouting toward Talavera la Real. Only two squadrons would turn up, arriving at Badajoz and marching with Cole’s men before joining Otway’s formation.

French cavalry units under General Andre Briche reached the Nogales on the afternoon of May 15, with Allied activity in and around Albuera noted. Blake’s absence was also apparent and Soult, after he arrived and surveyed the area, concluded the Spanish commander would reach Albuera late on May 16, or possibly May 17. Although wrong in this assumption, he correctly guessed the Allies were preparing to contest a French attack via Albuera and decided to exploit this. He would begin by making a convincing feint against the village, while almost simultaneously using the ground between the Nogales and Chicapierna to mask a vast flanking maneuver aimed at the Allied right.

Most French formations started reaching the area from midnight until the small hours, with the final units arriving at 7 am. Soult began May 16 with the unwelcome sight of Blake’s men positioned roughly where the flank attack was going to fall, the French marshal later claiming their appearance had been sudden and unexpected. This was a convenient excuse as thousands of men would have been impossible to miss, even if many of them were finally behind the reverse slopes. It is more likely the French believed their enemy would be poorly led and break when attacked in force, just as they had done many times before.

The weather that morning was inclement and the Allies assumed the French attack would come later, maybe even the next day. Their repose was upset by thousands of enemy troops advancing on Albuera by 8 am, with Soult trying to make his feint seem thoroughly believable. Godinot’s men led the advance, supported by some of Briche’s cavalry and squadrons from the 1st Vistula Lancers. This 600-strong regiment was led by Colonel Jan Konopka. The men sported dark blue uniforms with yellow fronts, collars, and cuffs, while their breeches had yellow stripes down the legs. Their lances were topped with pennants and they also wore distinctive shakos, called czapka.

Behind them came Werlé’s brigade and 2,000 cavalry. French artillery was also committed and began a duel with several guns opposite, just as skirmishers started needling Alten’s men. One hundred lancers then forded the shallow Albuera River south of the village, including two platoons that started to advance even farther. Long ordered the 3rd Dragoon Guards to throw them back, with the Poles inflicting and receiving a number of casualties as a result. They then rejoined their unit’s main body. Soult was no doubt satisfied to see Beresford taking the bait by moving Campbell’s brigade of Hamilton’s division, Colborne’s men, two Spanish battalions, and extra artillery closer to Albuera.

At that point it was about 9 amand the wheels were already turning on the flank attack as V Corps’ infantry, supporting artillery, and an array of cavalry started moving between the Nogales and Chicapierna. Beresford was informed of this via a picket’s report, which he appeared to ignore. The clue became more obvious when Werlé and his accompanying cavalry held back from committing to Albuera, eventually back-tracking toward the same ground the other formations had passed through. It was only when a Spanish messenger arrived and reported a suspected enemy advance over the Chicapierna that Beresford realized Soult was pulling the proverbial rug from under his feet.

The Allied commander galloped over to Blake, requesting the Spanish move their battle line several hundred yards south and realign themselves to oppose a French advance. Beresford then left to organize the shifting of Anglo-Portuguese formations, with an uncertain Blake belaying his orders. However, Zayas took 2,000 men south and assumed a position on the hill north of the shallow valley. The 2nd Battalion Royal Guards and 4th Battalion Royal Guards were in line, with Battalion Irlanda and Battalion Voluntarios de Navarra behind in column. Zayas also had Colonel Jose Miranda’s battery of six 4-pounder guns in close support.

Under lowering clouds, thousands of French troops could be seen entering the clear ground west of the Chicapierna, with Soult committing a total of 14,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry to his flank attack. Blake finally recognized the danger and ordered the realignment, although it took time because of Spanish inexperience in drill and maneuver, their difficulties compounded by instructions that were, in the opinion of one British observer, both tedious and pedantic. It was at this point Beresford arrived and took complete control, with Blake apparently nowhere to be found until after the fighting.

Zayas had extended his line by now; Battalion Irlanda, the 2nd Battalion Royal Guards, Miranda’s guns, and the 4th Battalion Royal Guards were deployed west to east, while Battalion Voluntarios de Navarra remained in immediate support. Units under Lardizabal and Ballesteros were moving up farther east as the remaining Spanish battalions were placed in reserve several hundred yards behind, to the north. Meanwhile, Spanish cavalry positioned ahead of Zayas was withdrawing under pressure from their French opponents, retreating northwest of the Allies’ new right wing. They would be joined by other cavalry, raising their number to approximately 2,000 men, including 800 British sabers, and with Lumley now in command. Cole’s 4th Division moved behind them and continued to act as a reserve.

Zayas had placed three light companies on the hill south of the shallow valley and they had also fallen back. This position had excellent views and the French initially unlimbered horse artillery here, replacing them with V Corps’ guns as Soult’s cavalry commander, General Nicolas de Fay de La Tour-Maubourg, took his forces farther west. V Corps’ 1st Division was then organized to begin its advance. It was previously assumed the unit adopted a massive T-shaped, mixed-order formation. This theory is now disputed and two large columns were most likely used—the left-hand attack aimed at Battalion Irlanda, the right targeting the 2nd Battalion Royal Guards and Miranda’s battery.

Spanish skirmishers behaved with confidence and kept their French counterparts at bay, but this was just the preliminary phase and Zayas’s line was soon being hammered by artillery fire. Miranda’s guns responded by targeting the enemy straight ahead, with the skirmishers on both sides falling back as Girard’s lead units trudged well into range, closing to within 60 yards, and orders to fire were bellowed, a Spanish volley thundering out. Girard now made an understandable but critical mistake: he had his battalions extend left and right to enter a musket duel, as was the usual practice, but he would have been better served by having his men press forward and attempt to overwhelm the enemy in a gigantic melee, recalling the earlier tactics of the French Revolutionary Wars.

It is easy to imagine the shouts of frustration and despair among the French front ranks at this stage. “Our soldiers fall left and right…. In vain, the leaders try to revive confidence through their example,” Captain Edouard Lapene recalled. Gazan came up to assist and was wounded, as was the leading brigade’s commander, General Michel-Sylvestre Brayer. Order was eventually brought out of the chaos and Zayas’s men experienced punishing fire in return, although help was at hand for the Spanish; Stewart’s 2nd Division was approaching, with Colborne’s brigade at its head and accompanied by Captain Andrew Cleeve’s KGL battery.

known as the “Buffs” for the color of their coat facings.

The British took a number of losses as cannon balls, either falling over Zayas’s line or ripping through it, hurtled into their columns. Colborne was accompanied by Stewart, who noted an opportunity to deploy the brigade at an oblique angle down the enemy’s left to deliver lethal enfilade fire. However, he refused Colborne’s request to put the men into line first. The Buffs were in front, followed by 2/48th, the 2/66th, and the 2/31st. Cleeve’s cannons were also unlimbered, with four guns close enough to start shooting canister—metal cases packed with musket balls.

Colborne asked Stewart to keep the Buffs in column, anchoring the brigade’s right and able to form an infantry square at speed if threatened by cavalry. This request was also denied. Two British volleys were then fired and Stewart called for a charge, even though the 31st was still moving up and the 66th was only partially deployed. He personally led his troops into the enemy’s left and caused it to waver, although resistance quickly stiffened and the French forced Colborne’s men to retire after several minutes of vicious hand-to-hand fighting.

The weather had become increasingly grim, including irregular squalls and bursts of hail, but Tour-Maubourg would have seen the British approach and possibly witnessed some of the melee through the smoke of battle. He would have also noted the enemy’s exposed right flank and the opportunity this presented to inflict serious damage and relieve pressure on the 1st Division. He selected 1,000 men to make an immediate charge. The strike force was composed of the 1st Vistula Lancers, 2nd Hussars, and units from the 10th Hussars. The lancers took the lead.

Two British logistics officers near the battle line, but far enough away to have an uninterrupted view, noticed this formation approaching; Lieutenant Charles Bayley thought Allied cavalry would intercept them, while Captain Robert Waller was less sure and raced toward the Buffs, warning Major Henry King. He suggested the battalion swing its right-hand companies back in readiness to receive an enemy charge, while King argued Waller should follow protocol and speak instead with the battalion’s commander, Lt. Col. William Stewart. The right-hand companies were eventually swung back—an impressive feat in the midst of battle—but precious time had been lost and the cavalry was closing fast.

Some in the Buffs noticed the lancers and their uniforms with yellow facings; the miserable weather and smoke made it harder to tell, but surely they were Spanish. Perhaps it was another one of their contingents withdrawing north? In addition, it was unlikely anyone in the Buffs knew of the Poles, while some would have heard of or even seen Spanish lancers in the past. The mistaken identification, and the subsequent orders to withhold fire, lost the brigade its final chance to take the sting out the enemy’s attack, the horsemen slamming into their shocked opponents almost unopposed.

With the battalion being ripped apart, the king’s colors were passed to Lieutenant Matthew Latham who received ghastly wounds in their defense. After being told to surrender the flag, he had shouted, “I will surrender it only with my life!” Several British cavalrymen of the 4th Dragoons suddenly dashed into the fray and distracted the enemy long enough for Latham to hide the colors in his jacket. Amazingly, he would survive the fighting and recover, albeit badly disfigured and his left arm amputated. The regimental colors were lost in the fighting but were later found discarded on the battlefield.

The 48th and 66th were also obliterated by the charge, with all of their colors taken. “Waller had held up his hands asking for mercy but [a] ruffian cut his fingers off,” wrote Lieutenant John Clarke of the 66th. Fortunately, Waller survived his wounds. Stewart and his divisional staff scattered, as did Zayas and his personnel, while Cleeve’s battery was also targeted, losing almost 50 men—most of them captured—and a howitzer towed away. Located farthest from the point of impact, the 31st was able to form a hasty square and warded off the horsemen.

The Allied cavalry’s ability to respond was limited because Lumley needed to maintain his men’s cohesion, especially if called on to guard a retreat. Nonetheless, he committed two squadrons from the 4th Dragoons and two Spanish squadrons to sap some of the enemy’s vigor. Their efforts not only assisted Latham but helped many of Colborne’s men flee or evade capture, including Colborne himself. But four squadrons were never going to be enough and they were forced back, with bolder lancers and hussars free to gallop behind the Spanish line and ahead of Hoghton’s brigade, which comprised the 29th, 1/57th, and 1/48th.

Companies from the 29th started firing in response, almost setting off a chain reaction as men of the 57th began shooting as well. A friendly fire disaster loomed as the Spanish were close by, albeit at a higher elevation, prompting Lt. Col. William Inglis, the 57th’s commander, to dash out in front and successfully call on his men to stop. In the meantime, several lancers had hurled themselves toward the Allied commander and his staff, with one even reaching Beresford. The Pole was hauled out of his saddle by the marshal and flung to the ground, where he was promptly finished off by the escort.

After several more minutes, and with the enemy cavalry finally gone, it was decided to withdraw the Spanish and replace them with the rest of 2nd Division. Their achievement had been immense, having both stalled the enemy and inflicted a fearsome toll in the process. Yet it appears some were concerned about accusations of cowardice. Lieutenant Moyle Sherer of the 2/34th (Abercromby’s brigade) later recalled how a Spanish officer pleaded with him. “He begged me, with a sort of proud and brave anxiety, to explain to the English that his countrymen were ordered to retire, but were not flying,” wrote Sherer.

It was now approximately 12 pm, with a pause on the French side, too, as V Corps’ 1st Division was replaced by its 2nd Division, which was now under the control of Maransin as Pepin had been mortally wounded. Some light infantry was also sent ahead to occupy the hill just vacated by Zayas, although the British easily pushed them back. The 31st, Colborne’s last surviving unit, deployed just west of Hoghton’s men, while Abercromby’s brigade, initially facing a composite unit of French Grenadiers, took the eastern side.

Maransin ordered his men to deploy into line and reignite the musket duel once more, with Hoghton fatally injured early on and Inglis taking over until incapacitated by canister shot. Lying on the ground, he shouted words of encouragement to soldiers of the 57th that became part of British Army lore: “Die hard, 57th, die hard!” This story’s veracity has recently been questioned but, regardless of being true or not, the regiment would proudly and justifiably be nicknamed “The Diehards” because of it.

Despite their best efforts, the British advance ground to a halt in the face of almost overwhelming fire. “Our line at length became so reduced that it resembled a chain of skirmishers in extended order,” wrote Lieutenant Charles Leslie of the 29th. Beresford urgently needed more men forward and ordered battalions from the Spanish reserve to advance, only to be met with sullen refusal. In his fury, he dragged a nearby colonel forward, hoping the battalion behind would follow. Nobody moved. Increasingly desperate, the Allied commander ordered Hamilton’s division to come up.

Unfortunately for the Allies, Hamilton had decided to support Alten and it took time to find him and start extricating his men. Beresford then left his position to discover what was happening, while staff officer Lt. Col. Henry Hardinge rode over to Cole and, acting independently, urged him to bring up the 4th Division. This presented the divisional commander with a potentially career-wrecking choice. Should he stay in reserve as instructed or advance? Cole sought the advice of other fellow officers and then chose to fight.

Mindful of the cavalry threat, 4th Division moved in broad echelon and in mixed order, with Brig. Gen. William Harvey’s Portuguese brigade taking Cole’s right and Lt. Col. William Myers’ fusilier brigade his left. There was also a battery of guns, the three light companies from Kemmis’s brigade, and a company of sharpshooters from the Brunswick-Oels Regiment who were equipped with rifles. Cole had approximately 5,100 troops underway, with Lumley’s cavalry offering support.

Soult saw the movement and ordered Tour-Maubourg to contest it, while also telling Werlé to advance his brigade. Tour-Maubourg’s men threw back Spanish cavalry ahead of the 4th Division and then primarily targeted Harvey’s brigade, possibly thinking the Portuguese would offer less resistance. They were wrong in this assumption as solid firing kept them at bay. Overall, the nature of the fighting was scrappy and, from the French perspective, ineffective as the 4th Division continued to advance, although Myer’s men now had to contend with Werlé’s attack columns.

They managed to stall the French with some well-aimed volleys and Werlé responded by having his men deploy into line, making the same mistake as Girard and Maransin. This decision lost an opportunity to grapple with the enemy and it would also cost men their lives, including Werlé’s own. Nonetheless, French return fire was telling and backed up with plenty of cannon shot. Sergeant John Cooper from the 2/7th noted the effect on British ranks. “Under the tremendous fire of the enemy our thin line staggers, men are knocked around like skittles, but not a backward step is taken,” he wrote. Myers was mortally wounded, while Cole took a musket ball to the thigh.

However, the British maintained their momentum and the fusiliers fired several volleys that were followed up with charges. The French 55th Line almost lost its Imperial Eagle standard in one melee, until it was recovered just in time by the bravery of a subaltern leading a small host of men. In desperation, Soult ordered the lancers forward again, although they were held back by accurate shooting. A few managed to break past the enemy line and capture some prisoners but it was nowhere near enough to stall Cole’s men.

In the meantime, to the northeast, Alten had been ordered by Beresford to withdraw from Albuera and cover the road to Valverde, while Campbell’s brigade was told to hold positions near the village. The Germans were promptly ordered back into Albuera when the Allied commander realized events had turned in his favor. Alten noted the enemy had yet to move up in force and that recapturing the village proved fairly easy, although localized attacks continued for some time after the battle proper had finished.

The Allies decisively turned the tide at 2:30 pmas Werlé’s men finally cracked. “They break and rush down the other side of the hill in the greatest mob-like confusion,” recalled Cooper. Almost simultaneously, and following advice given by Hardinge, Abercromby’s men were starting to envelop the French 2nd Division’s right. Sherer remembered bayonets being drawn and the men cheering until a body of French cavalry was seen, stopping them from making a charge. Nonetheless, some of the French were prompted to flee, while the British fired into those who remained. “The slaughter was now, for a few minutes, dreadful,” Sherer wrote.

V Corps’ 2nd Division broke not long afterward, its resolve weakened by the enemy’s volleys and the loss of Maransin, who had been badly wounded. They streamed toward the Chicapierna alongside the men of 1st Division and Werlé’s brigade, with Soult forced to make a rapid retreat. However, V Corps’ guns inflicted heavy damage on the advancing Allied ranks, while Tour-Maubourg’s cavalry moved across, further slowing the enemy’s pace. French units started to rally once over the Chicapierna, the artillery then brought across to offer close support.

The battle sputtered to a halt not long afterward as Beresford started recalling his men. It was a prudent choice. Losses among the Spanish had fallen disproportionately on their best units and it would have been too much to expect their other battalions to perform the maneuvers required during an attack. Later on, it was determined that Blake’s men suffered 1,375 casualties (a 9.5 percent loss rate). The Portuguese had suffered far less, with 387 lost, although their formations were now the backbone of Beresford’s army and needed in case Soult decided to mount another attack. In addition, the task of renewing the siege of Badajoz still lay ahead.

The carnage among the British formations would have been readily apparent, with an eye-watering 4,161 casualties later tallied (nearly 40 percent of all British soldiers present). Colborne’s brigade took 1,413 losses out of 2,066, with approximately 500 captured, although many of these men escaped and rejoined their battalions in the days that followed. Hoghton’s brigade recorded 1,046 casualties out of 1,651 men present, with almost all either killed or wounded, while Myers’ men lost 1,045 of 2,015 present. Total Allied casualties stood at 5,915 men.

Soult claimed to have held the field in his post-battle dispatch and disingenuously reported almost 3,000 losses for 9,000 inflicted. “Our troops are covered in glory,” he said, which was certainly true of the lancers and hussars who had crushed Colborne’s brigade and delivered one of the Peninsular War’s most devastating cavalry charges. Soult later admitted to a total of 5,900 casualties, although the actual figure has been estimated at upward of 8,700, with V Corps’ infantry and Werlé’s brigade suffering the greatest blows. The cavalry lost 500 men, including 130 from the 1st Vistula Lancers.

The volume of wounded was almost too much for both sides to cope with and many serious cases were left to die by overwhelmed surgeons. Burial and cremation details soon got to work, while the rain became incessant by the evening, adding to everyone’s misery. The French were forced to leave many of their badly injured behind when Soult’s army finally retreated two days later. Those lucky enough to reach a hospital then faced unsanitary conditions and the dangers that went with them. George Farmer of the 11th Light Dragoons recorded the trauma of assisting a large batch of Albuera’s wounded. “Everything seemed to be tainted with effluvia from [their] cankered wounds, and my dreams were all such as to make sleep a burden,” he recalled.

Wellington arrived at Elvas on May 19 and was unhappy with Beresford’s initial dispatch, a somber account of a battle almost lost. Like Soult, he also saw the need to report a better result. “Write me down a victory,” Wellington insisted. But Beresford would still face censure afterward; he was frequently in the wrong place at the wrong time, while he seemed content to react to events rather than dictate them. Wellington visited the battlefield on May 21 and was unsettled by what he saw, although he remained fully supportive of Beresford. Nonetheless, there was a telling incident when, on visiting wounded men of the 29th, one of the veterans plucked up the courage to tell him a sincere truth: “If you had commanded us, my Lord, there wouldn’t be so many of us here.”