By Jay Marquart

The sound of German artillery shells shrieking overhead from across the Siegfried Line was not the wakeup call Technical Sergeant Robert Walter of 3rd Platoon, L Company, 3rd Battalion, 393rd Infantry Regiment expected to receive on the morning of December 16, 1944.

He had experienced enemy shelling before. Since mid-November, when the 99th Infantry Division assumed responsibility for the sector of the Ardennes Forest previously manned by the 9th Infantry Division, Sergeant Walter and his fellow 99ers had been the recipients of regular artillery barrages that were carried out with predictable German efficiency. Every day at the same time, the periscopes on the bunkers across the Siegfried Line rose out of their ports. A short time later, a half dozen rounds would come crashing down on the American lines. After that, the guns fell silent for the rest of the day.

“That Ends Our Daily Ration!”

The men of the Checkerboard Division had started calling this their “daily allowance” and even found some comfort in the routine. Sergeant Walter and his foxhole mates figured the present bombardment was just more of the same and that, for whatever reason, the Germans were getting things done a little early that morning—0530 to be exact.

Soon, though, it became apparent that something was very different about this day’s enemy fire mission. Rather than a leisurely six rounds for the entire attack, that number of shells now rained down in a matter of seconds. Bright flashes lit up the darkness, the ground shook, and the noise was incredible.

Also, instead of dying out after a few minutes the barrage continued for what seemed like forever—and only grew in intensity. “That ends our daily ration!” one of the men with Walter quipped over the din as they huddled in their foxhole. To the 22-year-old technical sergeant, however, something big was obviously going on.

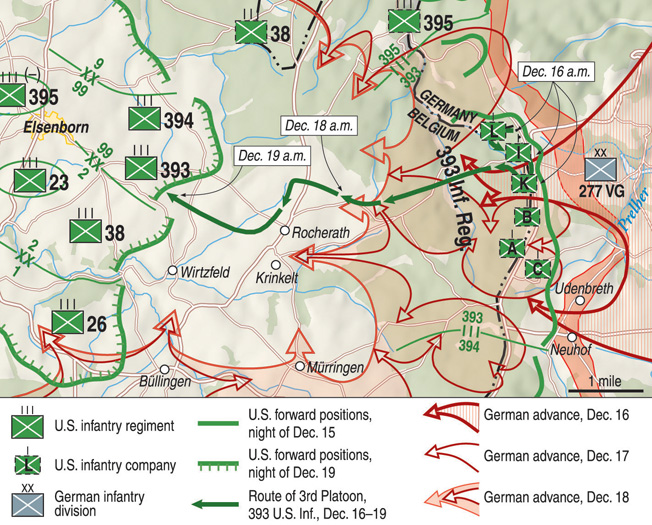

What puzzled Walter was that none of the shells seemed to be aimed at the thin line of infantrymen stretched along the International Highway, a north-south road essentially marking the border between Belgium and Germany. Instead, the target appeared to be farther west. He concluded that the enemy gunners were trying to knock out the 99th Division’s artillery battalions located a mile or so northeast of the twin villages of Krinkelt and Rocherath, Belgium.

At approximately 0730, the shelling lifted. Third Platoon and the rest of L Company stayed low in their foxholes, however. The sound of artillery was now replaced by rifle and machine-gun fire coming from seemingly everywhere around them. The rate of fire was especially heavy to the south, in the vicinity of L Company’s brother companies I and K.

The Wahlerscheid Offensive

This baffled Sergeant Walter. He could understand it if all of the noise was coming from the north, in the direction of Monschau. For the past three days a regimental combat team consisting of two battalions from the 99th’s 395th Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Battalion from his own 393rd had been supporting the 2nd Infantry Division’s efforts to seize the Wahlerscheid road junction inside the German border. The Wahlerscheid offensive was critical in the Allies’ larger effort to capture the Roer River dams, which were key to their advance across the Roer Plain. The Germans knew this, too, and had waged a ferocious defense to ensure the Wahlerscheid crossroad stayed in their hands.

To support the Wahlerscheid drive, the remainder of the 393rd and the 394th Infantry Regiment to its south (the third infantry regiment of the 99th Division) had staged limited objective demonstration attacks all along their front lines. Their goal was to occupy as many enemy troops as possible to discourage German commanders from relocating these resources to the battle up north. The action had been brisk at times but nothing like what Walter was now hearing to his right. A significant action was underway.

Robert Walter: Platoon Leader and Sergeant

As he continued listening to the unseen battle raging nearby, Sergeant Walter again focused on his unique, and not entirely welcome, position within 3rd Platoon. Like every platoon in the 99th, the 3rd had been led by an officer, a second lieutenant, when the division entered the line. Soon after arriving in the Ardennes, however, the lieutenant made a clumsy jump out of the bed of a truck and fractured an ankle so badly that he had to be removed from combat. Due to the manpower shortage at that point in the war, no replacement was immediately named. So, for the time being, Sergeant Walter had become 3rd Platoon’s leader as well as its sergeant.

Until now, the young NCO had not found his dual role too overwhelming. But as the small arms exchange to the south continued growing in volume, the weight of his responsibilities began to press on him. He wished his company commander, Captain Paul Fogelman, would radio to let him know what was happening. The captain’s call finally came, but it was not at all what Walter had expected.

“Bob,” Fogelman’s voice crackled over the speaker, “I received a report that some Germans have infiltrated our kitchen area. Take your platoon back and clear them out.”

That was it? Along with the orders, Walter had hoped for an update regarding all that gunfire. But the captain did not act like he knew any more about the situation. “Yes, sir,” Walter replied. He was now more concerned than ever.

Clearing the Kitchen Area

Rousting his men from their foxholes, Walter briefed them on the mission and told them to take along only what they needed for the assignment, which in this case consisted mainly of rifles, ammunition, and grenades. The intent was to get the job done and get back to their foxholes as soon as possible, so everything not absolutely necessary was to be left behind. Within minutes, the platoon was headed west toward the company kitchen area located roughly three city blocks from the front line.

It might as well have been three miles. In the dense woods, the men could not see more than a few feet ahead of them. Not wanting to get separated and not sure what they were walking into, they proceeded with caution.

Before the platoon got halfway to its destination, Sergeant Walter’s worst fears were realized. Germans, a lot of them, began appearing all around the unit. This was much more than a few infiltrators. The forest was crawling with enemy soldiers. Third Platoon had to fight its way into its own company kitchen area.

Once there, the men began cleanup operations while Sergeant Walter radioed back to the front lines. “Hey, something’s really gone wrong!” he yelled into the handset. “There are more Germans back here than there are in front of us!” To Walter everything seemed to have gotten turned around and they were now fighting the war in reverse.

Despite the topsy turvy situation, 3rd Platoon’s order stood: clear the kitchen area. Surprisingly, the Germans there seemed more interested in continuing west than in trading bullets with Walter and his men. As the platoon moved in, these invaders moved out. Soon, the little patch of ground was back in friendly hands with the exception of one small building that no one had yet checked out.

Three Drunk Germans

By now, the sounds of battle from the surrounding woods had grown noticeably fiercer—and closer! Third Platoon went to ground, the men crouching or lying behind anything that offered even a measure of protection. Sergeant Walter desperately wanted to withdraw the platoon back to the company position, but he still was not sure about the status of that lone building. Under the circumstances, strolling up to the door and peeking inside did not seem particularly wise. The sergeant called to one of his men near the structure to throw a grenade at it, figuring the explosion would persuade anyone inside to come out.

The soldier’s toss missed the mark, and so did those of other platoon members who took a crack at the building. None could hit it. Since he had played a lot of softball as a kid, Walter finally decided he might have better luck. Rising to his feet behind a tree, he pulled the pin on a grenade, released the handle, counted to two, then stepped out and let fly.

Walter’s grenade did not hit its target either. But instead of falling short, it sailed over the roof of the building, exploding as it passed above the ridge. Shrapnel slapped down on the shingles; the noise inside must have been deafening. Despite being a serious overthrow, Walter’s effort had produced exactly the effect he had wanted.

At the same time, not 30 feet from where the sergeant made his throw, a flag rose from a foxhole that the L Company kitchen crew had dug sometime in the past. But its current occupants were not members of the 99th Division. Rather, they turned out to be three German soldiers with a machine gun who had decided to take cover there when 3rd Platoon showed up. Walter was stunned. He had no idea why they had not shot him down when he stepped out from behind the tree.

Third Platoon quickly moved to take the Germans prisoner. As these men were searched, Walter noticed something strange about them. They acted drunk. A couple of platoon members checked their canteens, and sure enough they contained alcohol.

“So that’s how they got them up for this fight,” Walter thought. “Sent them in drunk. Filled their canteens with liquor and then said, ‘Take off, boys.’”

“You Seem Kind of Lucky”

In the brief moments it took to disarm the Germans, the noise from the woods had turned into the zip and thwack of bullets cutting the foliage and striking objects all around, forcing the men of 3rd Platoon to take cover again. The battle was definitely headed their way. Everyone hugged the ground tightly.

During the firestorm, Private Snow managed to crawl up to Sergeant Walter, who was sheltering behind a tree. “Sergeant, do you mind if I stay near you?” he asked. “You seem kind of lucky.”

Lucky? Snow must have figured that since Walter had survived standing up to throw that grenade he had a streak of good fortune going. The sergeant and the private had trained together for two years, and Walter knew Snow to be a good soldier—quiet but competent. Snow was a Californian, and that had always struck Walter as funny—Snow from California. Right now, though, he could tell the private was scared to death. In the midst of the confusion, he felt compassion for the guy.

“Help yourself,” he replied.

Relieved, Snow moved close to Sergeant Walter, and the two men lay side by side as the gunfire intensified. A short time later, Walter said something to Snow, but the private did not respond. Glancing over at him, the sergeant was horrified by what he saw. Sometime in the last few minutes, a bullet had caught Snow between the eyes and he was dead. Walter never even felt him twitch.

No Sign of I Company

German infantrymen started pouring through the area. From the woods behind the Americans came the growling sound of enemy tanks—something 3rd Platoon was not at all equipped to handle. There was no time to contact the captain. Sergeant Walter knew he had to get his men out of the way. Otherwise, they would be prisoners or worse. But returning to L Company was out of the question. Motioning for the others to follow, he headed south toward I Company. They had no choice but to leave Private Snow’s body behind.

This move did little to improve the platoon’s circumstances, however. No matter how fast they traveled, they could not find the enemy’s flank but seemed permanently stuck in the middle of the German advance. Machine guns chattered and grenades exploded. Rifle fire filled the air. Guessing, dodging, hoping, and praying, 3rd Platoon kept pushing south, looking for any spot that could provide a defensive advantage.

The force of the attack carried the platoon completely through the I Company sector. As they passed through, the men were shocked not to find a single I Company soldier anywhere. By this time, I Company and the rest of L Company had pulled back to form a perimeter defense around the 3rd Battalion command post northeast of the twin villages, but no one in 3rd Platoon knew this at the time.

Worse yet, groups of enemy soldiers traveling west began cutting across the platoon’s route, separating some of its members from the rest of the unit. Sergeant Walter now found his already small command getting smaller by the minute.

Bad News from K Company

Third Platoon was finally able to stop its flight in the K Company sector, south of I Company, and what its men found there left them numb. As soon as the German artillery barrage lifted that morning, two battalions of Volksgrenadiers from the I SS Panzer Corps had slammed into K Company, wiping out two of its three platoons. A few survivors of this onslaught were still in the area, and they told Walter and his men that maybe 17 soldiers were left from both platoons. The rest had either been killed or captured.

More bad news followed. The traumatized K Company men reported that a couple of their buddies taken prisoner during the assault were wearing German belt buckles when captured. This infuriated their captors, who assumed these GIs had removed the buckles from the bodies of dead German soldiers they had killed, so they “re-removed” these souvenirs by slitting the Americans open with their bayonets.

The report sent a panic through 3rd Platoon, and each man did a quick inventory to ensure he did not possess anything that had once belonged to a German. Days earlier while on a patrol, some platoon members had come across a hollow tree stuffed with German money. Clueless as to why the stash was there, they decided some extra funds would come in handy once the 99th crossed into Germany and had stuffed their pockets full. Now, they pulled these bills and coins back out and threw them as far away as possible.

While this was occurring, Sergeant Walter remembered his own German item, an eye-catching little pin he had picked up in Krinkelt shortly before the 99th entered the line. The townspeople told him this decoration was given to any Belgian woman who became pregnant by an SS trooper as a reward for her contribution to the master race. Walter thought the pin was beautiful and carried it with him so he would not lose track of it. Taking it out of his pocket, he admired its beauty one last time and then tossed it into the underbrush.

Lying Low

Again, the roar of tank engines was heard, this time coming from the direction of the unpaved road from Hollerath, Germany, a southwestern route that intersected the International Highway and served as the dividing line between I and K Companies. Investigating this latest threat, Walter and his men could hardly believe their eyes. Scores of panzers accompanied by infantry were rolling down this muddy trail and headed west. The Americans had thought the road was impassable and probably mined as well. Now, the Germans were using it as a thoroughfare for their armor.

With no opportunity for other action, the soldiers of 3rd Platoon dove for cover wherever they could find it, hiding behind trees and bushes or burrowing into the snow. Walter found a spot in a clump of shrubbery so close to the road that if he had had a rod no longer than a fishing pole he could have tapped each tank as it drove by. It was the end of the line for Walter and his men. All they could do now was stay hidden and wait for the invaders to pass.

That did not happen soon. Hour after hour, the German tank and infantry procession continued. Eventually, the squeak of tank treads became so unnerving that one 3rd Platoon rifleman took a shot at a panzer. All this did was invite the next tank in line to fire a round in the direction of the shot. No one was wounded by the blast—the tank could not get its barrel down low enough.

Walter crawled around to all the men. “It’s no use firing at them,” he whispered. “We’re not going to stop them with rifles, so just lay low.” To the sergeant, he and his soldiers resembled ostriches helplessly sticking their heads in the sand. “What the hell am I going to do now?” he asked himself as he settled back into his hiding place.

“If Anyone Wants to Surrender, There Will be No Repercussions”

Late in the day, gaps started appearing in the enemy column, so Sergeant Walter decided to cross the Hollerath road with the prisoners his platoon had captured earlier and hike north in search of L Company. Despite the dense forest and the growing darkness, somehow he finally managed to find the company headquarters. Releasing his prisoners to headquarters personnel, he reported to his company commander.

Captain Fogelman had no new information he could share with his NCO platoon leader. The extent of the German offensive was still unclear; under these circumstances it was best for 3rd Platoon to remain where it was rather than risk trying to rejoin the company. Then the captain said something that sent a chill through Walter.

“If anyone wants to surrender, there will be no repercussions.”

The statement caught the sergeant by surprise but needed no further explanation. Captain Fogelman was acknowledging that 3rd Platoon’s situation was grim. If any platoon member decided to save himself rather than continue holding out, he would not face official punishment. It was a sobering consideration.

Unsettled, Sergeant Walter wrestled with himself all during his return to the platoon. He didn’t want to surrender and was sure his men didn’t either. So what should he tell them? It was a difficult call, but by the time he sneaked back across the Hollerath road, he had made up his mind. The company was not ready for 3rd Platoon to come in yet. They were to remain in place until a way out could be found. As he repeated this message to each group of men, he omitted what the captain had said about surrender and hoped he was doing the right thing.

Meanwhile, the enemy kept coming.

Word of the Malmédy Massacre

Sunday, December 17, brought more uncertainty to Sergeant Walter and his “lost” platoon. There seemed to be no end to the Germans’ advance down the Hollerath road. How did they ever manage to get such a large force that far forward without being noticed? And with the odds against it, how would 3rd Platoon survive? Increasingly, it looked like a hopeless situation.

As if the platoon’s predicament was not bad enough, late in the day word arrived that some Nazi outfit had gunned down a large group of American prisoners west of 3rd Platoon near a place called Malmédy. Walter and his men were aghast.

When this news broke, Sergeant Walter felt vindicated for not sharing what Captain Fogelman had said about surrender. On the other hand, every hour that passed put 3rd Platoon farther and farther behind enemy lines. The longer this battle continued, the harder it would be for soldiers on either side to abide by any form of recognized rules. By now, he was convinced the Germans knew where his platoon was hiding. If one of the passing units decided to take them prisoner, would they end up like those poor GIs near Malmédy? The Army never used the word retreat but referred to such actions as a “strategic withdrawal.” As he watched the enemy race by, Walter hoped somebody somewhere was working on a strategic withdrawal plan and would get it to them soon.

At roughly 2300 that night, during a lull in the traffic on the Hollerath road, 3rd Platoon was startled to hear the sound of a vehicle coming up the road from the west. The vehicle turned out to be an American medical jeep that had been sent forward to evacuate the wounded. The fact that this driver got through was miraculous to Sergeant Walter; Germans were thick on all sides. Apparently, they had seen the jeep’s Red Cross symbol and respected it—a heartening sign after the Malmédy news.

Despite their surprise, Sergeant Walter, his best friend Staff Sergeant Walter Levdansky, and several other soldiers came out of hiding to assist the driver. After helping load three litter cases onto the jeep, they watched the driver speed off into the night headed west. “Where in the hell do you think you’re going?” Sergeant Walter thought. The idea that the driver could make it back to the safety of the American lines was harder to fathom than the possibility of reaching 3rd Platoon in the first place.

Late on the morning of December 18, Sergeant Walter received word from Captain Fogelman that 3rd/393rd had been ordered to pull back to a new defensive position near a place called Elsenborn. Not certain what this meant for 3rd Platoon, Walter made another trip to L Company, seeking more information.

Two Disturbing Sets of Orders

“We think we’ve found a route back to our lines,” Fogelman said after Walter arrived. He explained that about 100 yards west was a little valley bordered on its far side by a hill. The valley ran north for some distance before turning west, and L Company was going to use this defilade to withdraw. But to mask this movement, one unit would have to create a diversion. Then he dropped a bombshell. That unit was 3rd Platoon. “I want you to keep your platoon where it is and give us covering fire while we pull out,” he added.

Taken aback, Sergeant Walter began to wonder what his commanding officer thought of him and his men. Did he consider them expendable? Who was going to cover their withdrawal? This “plan” sounded more like a suicide mission.

Captain Fogelman next briefed the sergeant on when and where 3rd Platoon was to reconnect with the company after the withdrawal, and then dismissed him to return to his men. As he was leaving headquarters, Walter overheard a directive that was even more disturbing than the orders he had just been given. An officer told several GIs to take the three prisoners he had brought in two days earlier into the woods and shoot them. Later, while Walter was still en route to his destination, gunshots sounded from the area where the officer had pointed.

“Okay, Let’s Go”

Back with 3rd Platoon, Sergeant Walter gathered his men and briefed them on their mission. Then he had them cross the Hollerath road in small groups. The platoon moved north to take up new positions nearer to L Company. At the time when the company’s pullback was to begin, 3rd Platoon cut loose with a brief but intense rifle volley in the direction of the advancing Germans.

This ignited a hailstorm of bullets and mortar rounds from the other side. But instead of being directed at 3rd Platoon, this barrage thundered down on the valley where L Company was trying to make its escape. How had they known, and how bad were things in that valley? Suddenly, the sergeant felt much better about the role his platoon had been given in this operation. Maybe the captain had done him and his men a favor after all.

Now, a game of chicken began as Sergeant Walter tried to determine whether the Germans that blasted L Company had left the area or were still out there waiting for 3rd Platoon to make its move. After an hour and a half, he called the men together.

“First of all, I’ve been told if you want to surrender, it’s no disgrace,” Walter said, finally sharing what Captain Fogelman had told him earlier. “We aren’t trained this way, but do you see that hill behind us? Personally, I’m going over it. If you want to follow me, you can. If you have a route you think is better, take it. The main thing is to get out of here and get back to our lines.”

To a man, the platoon voted to follow their sergeant.

Walter had one more precaution to take. Directing his men to redistribute ammunition so that each soldier had at least one full clip, he ordered the platoon to fire another volley at the Germans to see if they would answer in kind. After roughly 10 minutes, when there was no return fire, he gave the order: “Okay, let’s go.”

Fighting the Germans and the Elements

Although unconventional, Sergeant Walter’s plan worked to perfection. He and his men were cresting the hill before the Germans, who had been waiting for the platoon, realized what was happening and opened up with machine guns. Even then, they had been anticipating another move through the valley and had registered their weapons too low to have any effect. The bullets chewed harmlessly into the hillside while the platoon made good its break.

The greatest enemy facing 3rd Platoon now became the weather. The snow was already two feet deep and more was falling. It was miserably cold, and the wind was whipping the heavy curtain of flakes around so hard that visibility was practically zero. Unlike some other soldiers he had trained with back in the States, Sergeant Walter had made the most of his time in compass school. Now that skill became a lifesaver, keeping him and his men on course for their hookup with L Company rather than wandering aimlessly around the woods.

Third Platoon’s route took it through the sector previously occupied by the 99th Division’s artillery battalions. There the unit found big guns and towing vehicles, jeeps mostly, that had been abandoned in place because the withdrawing units did not have time to ready them for travel. Determined not to leave anything useful for the enemy, the men paused long enough to drop grenades into gun breeches and engine compartments. Then, realizing that the explosions might attract the attention of any German units nearby, they made a hasty exit.

A short distance away, though, the platoon stopped again when it ran across the artillery unit’s food dump; not food in packages—a literal garbage dump. Hunger overcame fear as men who had not eaten in three days scrounged through other men’s castoffs looking for something edible. Sergeant Walter managed to find a piece of bread that had not been totally demolished by the elements. His buddy Sergeant Levdansky was the big winner. He found a whole raw potato.

Rendevous with L Company

That evening as darkness settled in, the worn out men of 3rd Platoon finally reached their rendezvous point with L Company, a section of woods to the east of the twin villages. The place was fairly open with sparse underbrush but still offered good concealment for L Company and the assorted stragglers from other units who had assembled there. Relieved to be back among so many friendly faces, Sergeant Walter and his men relished the prospect of catching a little shut-eye before making the final push to their new defensive positions.

But sleep was in short supply that night. As always, the Germans seemed to know exactly where L Company was and threw a steady stream of phosphorous flares over its position, lighting up the area like it was daylight. Instead of getting some much needed rest, the men of 3rd Platoon, along with the others, were forced to stay awake, bracing for sniper fire and an artillery attack that never came.

The flares finally tapered off around midnight on December 19. Shortly afterward, L Company crept away under cover of darkness, trudging northwest for hours through the snow and ice to rejoin 3rd Battalion at a place that was not even on the map but would soon become renowned because of its stubborn defense by the American units dug in there. They stopped SS General Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army dead in its tracks. That place was Elsenborn Ridge.

Technical Sergeant Robert Walter had no inkling that this destiny lay ahead as he stared wearily at the boomerang-shaped piece of high ground in the faint morning light. After three gut-wrenching days behind enemy lines, caught between indescribable firepower while enduring fear, cold, hunger, and the threat of capture or death at any moment, he had already gone through hell and survived. Elsenborn Ridge was not heaven by a long shot, but at least it offered his 3rd Platoon the chance to live and fight another day.

And for now, somehow, that seemed like more than enough.

Epilogue

Sergeant Walter survived the war and returned to his home in Fostoria, Ohio, where he served as a police officer for nearly a decade before entering private industry. Throughout his working career, he also gave freely of his time as a volunteer to many civic organizations in the Fostoria community. Sergeant Walter passed away April 19, 2014, at the age of 91.

Jay Marquart is a freelance writer from Bluffton, Ohio, whose writing has appeared in such publications as Horse & Rider, Military Medical/ CBRN Technology, and Vietnam.

These germansoldiers (pows) received better treatment than the black american soldiers after the war.

One is left to wonder if TSgt. Walter received a valor award for his actions during that period. Seems to me at least a Silver Star was in order. . . .