By Arnold Blumberg

February 1941 saw the fortunes of war favor the British in the North African wasteland of Cyrenaica (modern Libya). Two months prior the Italian 10th Army, over 250,000 strong under Marshal Rodolfo Granziani, had been swept from the area sustaining 12,000 men killed and missing, another 130,000 captured, with the loss of 400 tanks, hundreds of aircraft, as well as 850 artillery pieces.

This crushing defeat had been inflicted by a Commonwealth force under the command of Lt. Gen. Richard N. O’Connor, numbering just 36,000 soldiers, 300 tanks, 190 aircraft, and 150 cannon. O’Connor’s loss had been under 2,000 men.

Anxious to save his ally Benito Mussolini from further humiliation, Adolf Hitler dispatched two German panzer divisions to North Africa under the leadership of Lt. Gen. Erwin Rommel. By April 1941, Rommel had taken back the barren Cyrenaica, invested the port town of Tobruk with its Australian garrison, and driven the British forces, renamed the Eighth Army, back across the Libyan-Egyptian frontier. The British government was determined to reverse this unexpected setback.

Ordered to throw the Italian-German foe out of Libya, relieve Tobruk, and eventually conquer Algeria, thus erasing the presence of the Axis in North Africa, Eighth Army embarked on several fruitless counteroffensives in the spring of 1941. The first, Operation Brevity (May 15-17), after initial success, faltered from lack of strength to carry it through. The second effort, Operation Battleaxe, launched on June 15, was defeated two days later by a strong counterattack from the panzers of Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

Operation Crusader

As the British repaired over the Egyptian border to lick their wounds after Battleaxe, Prime Minister Winston Churchill urged his new Commander-in-Chief Middle East, General Sir Claude J.E. Auchinleck, to prepare another invasion of Libya. Churchill demanded an immediate attack. However, Auchinleck wanted to carefully build up his strength in order to bring as much military might as possible to bear next time Eighth Army met the enemy. The result was that despite unrelenting pressure from Churchill, the general, from July to November, refused to move while slowly and deliberately marshaling and reorganizing his resources and plotting his next move.

Auchinleck’s laborious summer and fall preparations were designed to initiate Britain’s decisive offensive in the Western Desert, codenamed Operation Crusader (also referred to as the Winter Battle). The C-in-C Middle East had decided, in keeping with the aim of recapturing the whole of Cyrenaica, that the immediate objective of the offensive would be to destroy the enemy’s armored forces. Toward that end, in September he instructed Eighth Army commander Lt. Gen. Sir Alan Cunningham to study two broad plans: one for an advance from Jarabub through Jalo to cut the enemy’s supply line in the vicinity of Benghazi, the other for a main thrust directly toward Tobruk with feint attacks in the south. Regardless of the line of advance chosen, Auchinleck specified that the British would carry out a general offensive into Libya in early November.

Responding to his chief’s directive, Cunningham rejected a drive for Benghazi by way of the desert flank. He felt that such a move might not induce the enemy to respond at all since his forward area supplies would make him independent of the need to draw logistical support from the threatened town. Further, the time and distance required to reach the Benghazi vicinity would cost the British the element of surprise, stretch the attacker’s supply lines, and limit friendly air power support the farther west the advance was made. Instead, Cunningham favored a direct move on Tobruk. This would allow British armor to stay concentrated, avoid extended and vulnerable lines of communication back to the Egyptian border, and assure a German reaction and the desired early tank battle since the Axis could not stand idly by while Tobruk was relieved. This plan was accepted in the first days of October.

The Preparations on Both Sides

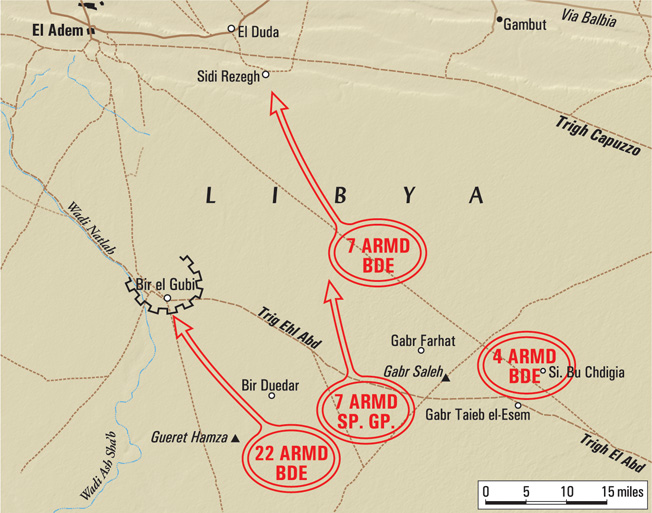

Operationally, Cunningham planned to cross the frontier between Sidi Omar and Fort Maddalena. The main body of the British armored force would move northwest with the object of engaging the hostile armor near Tobruk, after which the siege would be raised in conjunction with a sortie by the garrison. Meanwhile, another force would contain and envelop enemy frontier troops and then go on to clear the area between Bardia and Tobruk. The 30th Corps, under Lt. Gen. Charles W. Norrie, held all three of the British armored brigades. It was tasked with the destruction of the enemy tank forces and preventing them from attacking the left flank of 13th Corps, the mainly infantry formation under Lt. Gen. Alfred Goodwin-Austin, which was to operate in the frontier area.

As a prelude to the decisive tank action, the British armored brigades, 4th Armored Brigade Group, 7th Armored Brigade, and 22nd Armored Brigade, all part of British 7th Armored Division under Maj. Gen. W.H.E. Gott, would use the first day of the offensive to move to Gabr Saleh, a central point about 30 miles west of Sidi Omar. From there they would march north to Tobruk or Bardia according to how the enemy reacted.

Axis tank units were known to be near Gambut, including the 15th Panzer Division; just west of Sidi Azeiz was the 21st Panzer Division; and at Bir el Gubi the Italian Ariete Armored Division. In addition, three Italian and one German infantry division closely invested Tobruk. The breakout from Tobruk was not to commence until the German-Italian armor had been defeated or otherwise been prevented from interfering with the attempt. When the latter had been accomplished, the garrison from Tobruk would capture the El Duda escarpment while 30th Corps took the Sidi Rezegh escarpment. Between these two ridges, situated south of Tobruk, ran the main enemy line of communication.

While the British completed their preparations, the Italian and German high commands agreed that possession of Tobruk was the essential prerequisite to any advance into Egypt and then on to the vital British-held Suez Canal. As his own supply situation slightly improved after September, Rommel planned to attack Tobruk during the third week of November 1941. Although observing the signs of the British military buildup across the border in Egypt, Marshal Ettore Bastico, head of all Axis forces in North Africa, and Rommel, in charge of the Axis operational formations, discounted any imminent enemy advance. But even if the Commonwealth forces did attack Rommel felt confident that his mobile units could successfully deal with that threat if carried out before his own offensive began, or even while Tobruk was being attacked.

Rommel came to believe in early November that his adversary would make some move to divert his attention away from Tobruk but that it would be a limited diversion designed to delay his own plans to capture the city. As a result of his mind-set about British intentions, not fully cognizant of the extent of the enemy buildup of men, tanks, and matériel, Rommel resolved to make no hasty response to any initial move by his opponent regardless of what it might be. However, the development of Eighth Army’s battle plan hinged largely on the enemy’s reactions. This curious mix of expectations on both sides would cause all British and German planning to become rapidly irrelevant during the first days of the Operation Crusader.

An Uneven Advance

The weekend of November 16-17, 1941, saw Cunningham’s command—100,000 men, 600 tanks, and 5,000 assorted other vehicles—rumble over the 130 miles from its main railhead in Egypt at Mersa Matruh to the Libyan-Egyptian border. This was done in a driving rainstorm, which turned the desert dust into liquid mud. From there Norrie’s 30th Corps on the 18th motored 60 additional miles to the area around Gabr Saleh, as planned, while 13th Corps curled around the fortified Axis posts on the frontier.

At dusk the several elements of the armored fist of Eighth Army leaguered near the following points: 7th Support Group, a mixed mobile infantry and artillery brigade, screening the front of 7th Armored Division, south and east of Gabr Saleh; 7th Armored Brigade about 10 miles to the northwest of Gabr Saleh; 22nd Armored Brigade 10 miles due south of Gabr Saleh; and 4th Armored Brigade Group 10 miles east of Gabr Saleh astride the Trigh el Abd. Forming a cordon of infantry behind 30th Corps running from south of the 22nd Armored Brigade to the coast just east at Sollum were the 1st South African, the New Zealand, and 4th Indian Infantry Divisions of 13th Corps tasked with first cutting off enemy troops on the Egyptian frontier, then advancing westward.

The approach march to the vicinity of Gabr Saleh on November 18 was relatively uneventful. At mid-morning the tank columns halted their procession to refuel. Meanwhile, various armored car platoons spearheading the advance of 7th and 4th Armored Brigades raced westward in search of the enemy. A number of these scouting parties reported their German counterparts from the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 21st Panzer Division just ahead covering the Trigh el Abd. Sporadic clashes occurred between the opposing armored car sections, but casualties were few. On the negative side of the ledger, an alarming number of tank breakdowns had occurred—7th Armored Brigade lost 22 of its original 141 tanks, while 22nd Brigade was reduced from 156 to 136.

Countering the initial euphoria the British commanders and troops felt as a result of their accomplishments through the 18th was a growing uncertainty about what to do next. Cunningham and Norrie were puzzled. The entire Eighth Army had marched all day toward Rommel’s rear without causing a noticeable reaction on his part.

There had been no hardening of resistance, no local counterattacks, and no evidence of preparations on the Germans’ part for a major counterstroke. All this enemy inaction led Auchinleck to issue what can only be termed rather colorless orders for the next day. These merely called for making secure the prearranged battle positions and pushing out strong reconnaissance forces toward Bir el Gubi and the Trigh Capuzzo. These bland directives reflected a growing unease on the part of Army headquarters. Where was Rommel?

A Change of Plans

Rommel was in his advanced command post at Gambut. He had not the slightest intention of reacting seriously to what he was certain was nothing but a diversion staged to frighten the Italians at Bir el Gubi and Bir Hacheim, causing them to divert his attention from his main purpose of taking Tobruk, which was to begin 60 hours hence. So sure was Rommel that he refused the pleas of Lt. Gen. Ludwig Cruewell, head of the Afrika Korps, which included Rommel’s armored divisions, to send a German tank regiment to investigate reports of British armor in the neighborhood of Gabr Saleh.

While Rommel sat on his hands, one British commander summoned up the courage to act. “Strafer” Gott, leading 7th Armored Division, had no intention of losing the initiative his unit had achieved on November 18. He issued orders for 22nd Armored Brigade to probe toward Bir el Gubi, where the presence of the Italian Ariete Armored Division was known. At the same time, 7th and 4th Armored Brigades were to orient to the north and be prepared to battle German panzers if they appeared. Scout cars from 11th Hussars would screen both operations.

Two hours later revised orders from 30th Corps headquarters directed 7th Armored Division to occupy Bir el Gubi to the west with 22nd Armored Brigade. The 7th Armored Brigade was to occupy Sidi Rezegh to the northwest on a direct line to Tobruk. The 7th Support Group, moving between the two tank outfits, would cooperate with either 7th or 22nd Brigade as circumstances dictated.

The new directive, although giving impetus to action, entirely changed the original concept of Operation Crusader. Now the decision had been made to go straight for Tobruk without first eliminating the enemy armor, which was so central to the initial plan. In addition, 4th Armored Brigade Group was not to support the move to the west or north but remain in place east of Gabr Saleh to protect the left flank of 13th Corps. The vital need for a concentrated armored thrust had been jettisoned in favor of the wide dispersal of British armored assets.

Onward to Bir el Gubi

The early morning hours of November 19 witnessed the approach of 22nd Armored Brigade toward Bir el Gubi. It was known through prior intelligence that the entire Italian Ariete Division was there. Reconnaissance patrols from the 22nd had engaged in a sharp skirmish with armored cars attached to the Italian 20th Corps (Corpo d’Armata di Manovra, or Mobile Army Corps), which controlled all Italian tank and motorized infantry formations in Libya. After this scuffle at Taieb el Esem between Gabr Saleh and Bir el Gubi, the Italian cars withdrew northward.

The British tankers heading for Bir el Gubi were not combat veterans and lacked adequate training. The brigade, formed in 1939, had arrived fresh in Egypt on October 4, 1941. It took several weeks to acclimate to desert conditions. The formation was equipped with the new Crusader A15 tanks, which although very maneuverable were mechanically unreliable. The 7th Armored Brigade used the older A13 cruiser vehicles, while 4th Armored sported the American M5 Stuart light tanks, dubbed Honeys by the British. Little time was available for practical combat training before Operation Crusader commenced. However, this drawback did not deter 7th Armored Division’s command from assigning the 22nd to confront the Italians at Bir el Gubi.

Gott’s Fateful Assumptions about the Enemy

On the morning of the 19th, Gott instructed its commander, Brig. Gen. J. Scott Cockburn, to initiate a vigorous attack on the Italians at Bir el Gubi. The division commander felt that it would have been unwise to leave Ariete unmolested on his left and that its removal would have allowed easy occupation of the post by the 1st South African Division, thus securing the British desert flank. Further, it would present a good opportunity to blood the green British formation against a second-rate opponent in preparation for the much harder fighting it would encounter when the brigade faced the tougher Germans. Besides, the armored unit would be supported if necessary by the 1st South African Division following in its wake.

Gott may also have assumed, taking into account past battlefield performance, that separated from the Germans as they were, the Italians might simply flee rather than fight. Either way, the ejection of Ariete from Bir el Gubi would secure the 7th Armored Division’s left wing and force the Germans to commit tanks in support of their Italian allies and away from Tobruk.

Gott’s assumptions were not unreasonable, but he failed to consider that regardless of the performance of Italian tanks they would be fighting from defensive positions supported by artillery, a branch of the enemy army that had proved over the last year of desert combat to be a skillful and determined foe.

He also missed the point that any fight between the British and the Italians with about the same number of tanks would be more of an equal contest than assumed. The British Army’s Crusader I (Cruiser Mark VI) tank fielded by the 22nd Armored Brigade held a four-man crew, weighed 19 tons, was fast moving (27 mph), with maximum armor plating of 49mm at its strongest points. However, its paltry 2pdr (40mm) main armament was short ranged, and except for a few models not plentiful during Operation Crusader, could only fire armor piercing ammunition. Even worse was the complete mechanical unreliability of the vehicle. Rushed into service before proper testing, more were lost during the Desert War to breakdowns than enemy action.

After Bir el Gubi the brigade reported that it had lost 82 tanks, and another account stated that it had only 10 to 20 battleworthy tanks left. These figures included not only battlefield losses but also Crusaders lost during the two days leading up to and including the battle due to mechanical problems.

The Obsolete M 13/40

Facing 22nd Brigade’s Crusaders was the main Italian battle tank, the medium M 13/40. Rommel exclaimed that when he thought of these vehicles it made him sick since they were, in his opinion, obsolete. At the time of Operation Crusader, Rommel had 414 tanks, 260 German models including 15 PzKpfw. Is, 40 PzKpfw. IIs, 150 PzKpfw. IIIs, 55 PzKpfw. IVs, and 154 Italian M13/40s. Subtracting the obsolete Panzer Is and IIs and the 50 percent of his PzKpfw. IIIs that still sported the weak 37mm cannon, Rommel had to rely very much on the despised M13s as they comprised the backbone of his tank force.

Crewed by four men protected by only 40mm of steel plate, powered by an unreliable, underpowered engine capable of an average speed of 8 mph in the desert, and carrying a puny 47mm main gun (which fired both armorpiercing and high-explosive shells), and was not equipped with radios, the M13 was somewhat inferior (except in speed) in performance to its British Crusader challenger.

An Arrowhead Approach

Gott had not anticipated that the inadequacy of the British communication system would compromise his plans. Although most commanders were aware that a push for Bir el Gubi was set for that day, orders for the South Africans under General Brink were only issued early on the 19th and interpreted to mean that the South Africans would only move up and occupy that location after the British armor had captured it. As a result, vital friendly infantry and artillery support would be lacking when the 22nd Armored went up against Ariete at Bir el Gubi.

The brigade took position a few miles southeast of Bir el Gubi at 0900 hours; the bulk remained in place until around noon. It then advanced behind a screen of 11th Hussars armored cars with the 2nd Royal Glouscestershire Hussars (2nd RGH) on the right, 4th County of London Yeomanry Sharpshooters (4th CLY) on the left, and the 3rd County of London Yeomanry Sharpshooters (3rd CLY) forming a second line behind 4th CLY.

Each regiment, containing four squadrons of four troops of three tanks each, formed into an arrowhead, the base of which was occupied by the regimental headquarters squadron. Brigade headquarters, containing eight tanks, took station in the center rear of the battle line where it could cover the brigade’s artillery support provided by the eight 25pdrs of C Battery, 4th Royal Horse Artillery, and one troop of 2pdr antitank guns from the 102nd Northumberland Hussars, Royal Horse Artillery.

General Gambara’s Defenses at Bir el Gubi

Facing the onrushing British, the Italian 132nd Ariete (or Ram) Armored Division had been raised in 1939 and deployed to the Western Desert in January 1941, where several detachments from the parent division had fought from April through October 1941. At Bir el Gudi under General Mario Balotta, Ariete would fight as a complete unit for the first time.

Although Rommel had radioed General Gastone Gambara, Italian 20th Corps commander, on the night of November 18 telling him not to worry about an enemy attack in the near future, Gambara chose instead to listen to his own intelligence sources and warned Balotta that a British assault on his position was likely on the 19th. As a result, the men of the Ram Division were alert and prepared to receive the British if they came. They would do so with 146 M13/40 tanks, 16 105mm and 32 75mm field guns, 18 47mm antitank guns, and eight 20mm antiaircraft guns.

Division personnel had spent the autumn training with these weapons and had gained confidence in their ability to fight, especially in prepared positions. Ariete’s order of battle at Bir el Gubi included the 132nd Medium Armored Regiment (three battalions), Eighth Bersaglieri (light infantry) Motorized Infantry Regiment (three battalions), three companies of 47mm antitank guns, and the 132nd Motorized Artillery Regiment (three battalions).

In addition to intensive training, the men of Ariete spent early November 1941 fortifying the ground around Bir el Gubi. General Balotta created three main strongpoints called lozenges due to their shapes, each consisting of trenches, weapons pits, and connecting communication ditches. Each was occupied by a battalion of the Eighth Bersaglieri Regiment and backed by the divisional artillery as well as a battery of 105mm cannon assigned to Ariete from 20th Corps. In addition, seven 102mm naval guns capable of firing armor-piercing shells and mounted on trucks were present as antitank weapons. When the battle began, the tanks of 132nd Armored Regiment were stationed to the rear.

“The Nearest Thing to a Cavalry Charge with Tanks During the War”

At 0700 hours a company of 16 Italian tanks and a battery of 75mm field guns was sent south of Bir el Gubi as an observer screen. At 0800 hours shells from the 25pdr guns accompanying 22nd Armored Brigade started to fall near the Italians, but no hits were scored on the M13s.As tanks from the 2nd RGH approached, a series of charges and counter charges ensued, resulting in a stalemate that ended at 1100 hours.

With reports of more enemy tanks approaching from the northeast, the lone Italian tank unit rushed to the new danger point and engaged 40 Crusaders in a spirited 10-minute duel, which left eight British vehicles destroyed for three Italian machines put out of commission and seven more damaged. Outnumbered, the Italians retreated to the Bir el Gubi defenses.

The British tank crews were exhilarated by their first taste of combat and eager to finish off what they assumed was a demoralized and beaten opponent. The fighting resumed about noon when the 2nd RGH was joined on its left by the 4th CLY. Despite warnings from an 11th Hussars officer that the enemy ahead was in a strong position, of unknown strength, and that the tankers would need infantry if they were to capture their objective, the brigade commander ordered an attack on what he thought was a mobile defense post five miles east of Bir el Gubi.

In what one observer stated to be “the nearest thing to a cavalry charge with tanks during the war” the 2nd RGH and 4th CLY slammed into what turned out to be the well-constructed and manned lozenges. After the battle the brigade was accused of making repeated “reckless” charges instead of advancing by firing from alternate hull-down positions. This indictment is unfair since the lack of adequate artillery support and the determined and valiant actions of the Italian defenders working their cannon provided no choice but for the unsupported British armor to advance as rapidly as possible.

Attack on the Italian Right

The main thrust of the attack was directed at the Italian right, which put out such a volume of antitank and artillery fire that the subsequent confusion in the inexperienced British ranks caused the advance to veer toward the Italian center. There the assailants were greeted by deadly fire from dug-in infantry.

The range between attacker and defender was so close, 200 yards or less, that the antiquated 47mm antitank guns and 75mm cannon wreaked havoc on the charging British armor. After taking losses from the opposing infantry and artillery and then being counterattacked by M13s of the 9th Battalion, 132nd Tank Regiment, the British pulled back a few hundred yards to rethink their strategy.

After a brief radio conference between brigade headquarters and the battered 2nd RGH and 4th CLY commanders, the two bloodied units redirected their attack farther to the Italian right with 2nd RGH leading the way. The brigade once again proved its combat inexperience by rolling across the enemy front to its new jumping-off point. During this move, it sustained more tank casualties from enemy fire on its vulnerable flank without being able to return the favor.

Some Initial Success

As poorly executed as the new advance was, it did meet with initial success at about 1330 hours. The attack hit the Italian infantry of the 7th Bersaglieri Battalion just before the Italians had a chance to properly man their defensive positions and sight artillery.

As a result, as 4th CLY squadron leader Viscount Cranley recorded after the fact, the impetus of the British rush on the Italian entrenchments at first dismayed the defenders to such a degree that over 300 of them surrendered to the British tanks, but their captivity was very short lived. Seeing no enemy infantry to guard or direct them to the British lines, the Italian soldiers again took up their weapons to resume fighting. Meanwhile, the stand of the Bersaglieri had allowed tanks to mass behind the cracked Italian position, preventing a clean British breakthrough.

After their brief success the British tanks were pinned down by well-directed fire from dug-in Italian 47mm and 75mm guns. Follow-up squadrons from the 4th CLY and Lt. Col. R.K Jago’s 3rd CLY tried to work around both enemy flanks but immediately ran into hidden minefields and heavy artillery fire. Lack of fighting experience led elements of these regiments to fall into a trap around 1500 hours when they blindly advanced at what they thought was an Italian truck park. Instead it was a cleverly camouflaged anti-tank position manned by the 102mm naval artillery detachment. Within minutes of the attack, six Crusaders were blazing hulks in front of the Italian gun line.

A Running Battle

Throughout the day British tankers had urgently called for artillery fire to suppress the stinging Italian barrages that continually fell. The response to their pleas was usually silence since by mid-afternoon most regimental and brigade radio communications had broken down. When supporting artillery fire did infrequently occur it was feeble at best due to the small number of 25pdrs accompanying the brigade.

At 1530 hours a determined British relieving attack by the 3rd CLY to the northwest of Bir el Gubi was designed to help the effort of the 2nd RGH and 4th CLY then fighting in the center and northeast of the Italian positions. As the British prepared to move forward they were hit by the rolling armor of Ariete’s 7th, 8th, and 9th Tank Battalions, 132nd Armor Regiment, placed there to counter such an enemy move.

Each side deployed 100 tanks in this engagement. As the British pressed northward of Bir el Gubi at high speed, the Italians attempted to flank them. Italian artillery batteries turned to fire on the passing enemy tanks. After one hour, the running gunfight ended with the British defeated and retreating to the southeast. With the 3rd CLY diversionary effort thrown back, 2nd RGH and 4th CLY were ordered off the field, and the bloodletting at Bir el Gubi soon ceased.

A Defeat that Shook Operation Crusader

After the fight at Bir el Gubi, British tanks littered the field. The first armored battle of Operation Crusader was an Axis—more appropriately, an Italian—victory. Although early British reports, intended to explain the English reversal, claimed that some of the M13s were manned by German crews and that German PzKpfw. IV panzers and German infantry were involved in the battle, these assertions had no basis in fact.

Although the British admitted to a loss of only 25 Crusaders destroyed and 10 more damaged, it seems more likely that the Italian figure for British losses, about 50, is nearer the mark. The 22nd Brigade also reported that it had destroyed 45 Italian tanks and captured 205 prisoners. Ariete’s after-action reports paint a different picture, admitting that only 34 tanks were written off and 15 damaged but brought back into service later. The division claimed that four 75mm and 12 47mm guns were lost, 15 men were killed in action, 80 were wounded, and a further 82 were missing. In addition, 37 British officers and enlisted ranks were captured.

The Battle at Bir el Gubi affected the entire Crusader campaign. Ariete remained in position for a few days guarding the Axis flank and diverting British armor and infantry to watch it. This prevented the full weight of 7th Armored Division from concentrating its strength against the German panzers barring the gate to Tobruk at Sidi Rezegh. Helping to keep the enemy armor dispersed, Ariete also allowed conditions to exist for German tank victories over isolated British armored units—against 4th Armored on November 20th, 7th Armored Brigade and 7th Support Group on November 22, and the destruction of the 5th South African Infantry Brigade south of Belhammed on the 23rd and 24th, in which Ariete took part.

Rommel’s misguided “dash to the wire” on the Egyptian frontier on November 25 gained the Commonwealth troops enough respite to reconstitute their strength, relieve Tobruk, and send Axis forces packing once more, temporarily, out of Lybia in the waning days of December 1941. Ariete was one of the last Axis combat units to leave Cyrenaica, while 22nd Armored Brigade fought the final tank action against the Germans before retiring across the border into Tripolitania.

The Battle of Bir el Gubi, where Ariete and the 22nd Armored Brigade were first tested in combat, was described by General Norrie as “an encounter battle carried out too enthusiastically against prepared positions … not seen or recognized until the attack had been launched.”

My father fought in WWII in the 2nd RGH Tank Division.I have a few photos.