By Nathan N. Prefer

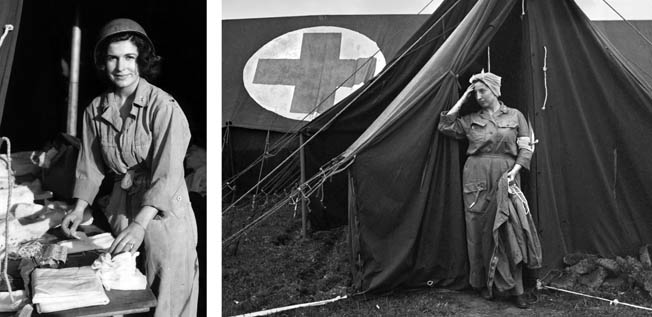

Of the many groups that fought in World War II and have been largely forgotten in the history of that great conflict, none are more neglected than the women who served and died doing their duty alongside the men of the United States Army.

Known as the United States Army Nurse Corps, they served from the first day of the war to the last, suffering deaths and wounds as they treated the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and civilians who were wounded or sick.

Prior to the United States entering World War II there were only a few hundred nurses serving in the U.S. Army. Most of these served somewhere within the United States at Army hospitals on the larger Army bases. Nursing was, for these women, a chance at a career and an opportunity to escape the economic depression of the 1930s and early 1940s.

To accomplish their goal, they had to endure a belief current in America during that period—that nursing was not a suitable vocation for a woman of good character. It was considered “indecent” because these women treated men as well as women with the most intimate of diseases and illnesses. Yet many women felt that call to duty and risked social condemnation to become nurses.

For many women, even those with nursing degrees, jobs were not easy to find during the Depression. As a result, many saw advertisements and joined the Army Nurse Corps or Navy Nurse Corps. Such jobs promised a steady salary, a chance to serve their nation and, if a nurse were adventurous enough, a chance for foreign travel. At the time, overseas assignments were strictly on a voluntary basis, but many nurses volunteered simply for the opportunity to “see the world.” Upon enlistment they were immediately assigned to a hospital and went to work.

For many women, even those with nursing degrees, jobs were not easy to find during the Depression. As a result, many saw advertisements and joined the Army Nurse Corps or Navy Nurse Corps. Such jobs promised a steady salary, a chance to serve their nation and, if a nurse were adventurous enough, a chance for foreign travel. At the time, overseas assignments were strictly on a voluntary basis, but many nurses volunteered simply for the opportunity to “see the world.” Upon enlistment they were immediately assigned to a hospital and went to work.

In 1941, an Army nurse had no official military uniform. Off duty, she wore her own civilian clothes. On duty, she wore the standard nurse’s uniform of the day adorned with her military rank and medical insignia. Most nurses were second lieutenants but, like most women in the work force at the time, they earned less than their male counterparts.

This disparity was attributable to the fact that Army Nurses were not “real” second lieutenants, but “relative lieutenants,” a term that had come into usage with the Army Reorganization Act of 1920, which was intended to protect the status of the World War I nurses. As a “relative” second lieutenant, a nurse in 1941 earned $70.00 per month with an additional $18.60 subsistence allowance. A male second lieutenant in the U.S. Army in 1941 earned $140.00 plus $37.20 subsistence allowance per month.

A World War II U.S. Army nurse had no formal military training. This was because she held no true military status and did not rate a salute from either enlisted men or other officers. Initially, nurses could not advance beyond the “relative” rank of major.

The majority of U.S. Army nurses serving overseas in December 1941 were located in the Philippines. About 100 of them served in the three main Army hospitals in and around the Philippine capital, Manila. By that December, while all dependents of American military personnel had been ordered to return to the United States as the threat of war with Japan loomed large, the Army continued to send its nurses to the Philippines. Indeed, the last two convoys suppling the American forces in the Philippines before Japan attacked both brought additional nurses. The last to arrive came just nine days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the Philippines, the main American stronghold in the Pacific. Across the international dateline it was Monday, December 8, 1941, when Japanese planes began to bomb American and Filipino installations on the main island of Luzon.

When the attacks began, the nurses were issued outdated World War I helmets, dog tags, and gas masks. Casualties were rushed to the hospitals, including the large Stotsenberg Army Hospital, where Army nurses, wearing either civilian dresses or white uniforms, treated 85 dead and 350 wounded men. Many nurses ran out onto Clark Airfield, still under air attack, to aid wounded men lying out in the open.

By Christmas Eve, 1941, General Douglas MacArthur’s plan to defend the Philippines had failed to materialize, and he ordered a withdrawal onto the Bataan Peninsula. Along with the combat and support forces, the nurses also moved to Bataan where conditions quickly became appalling. Here, for the first time, they were told to prepare themselves to be taken prisoner.

After sailing across Manila Bay to Bataan, the nurses found that the “hospitals” were mostly tents set up in clearings in the jungle. By this time the nurses were wearing mechanics’ coveralls, helmets, and carrying gas masks as standard equipment. Most of the nurses, having heard of the rape and murder of British nurses in Hong Kong, had secreted a vial of morphine to use as a last resort if capture by the enemy seemed imminent.

Between shifts, which often lasted 18 hours, the nurses sheltered in foxholes like any frontline infantrymen. Hundreds, soon thousands, of casualties needed their attention. Most lay on stretchers out in the open, there being no room for them under the few tents available. Nurses went among them constantly, treating their injuries or illnesses and making them as comfortable as possible under the extreme circumstances.

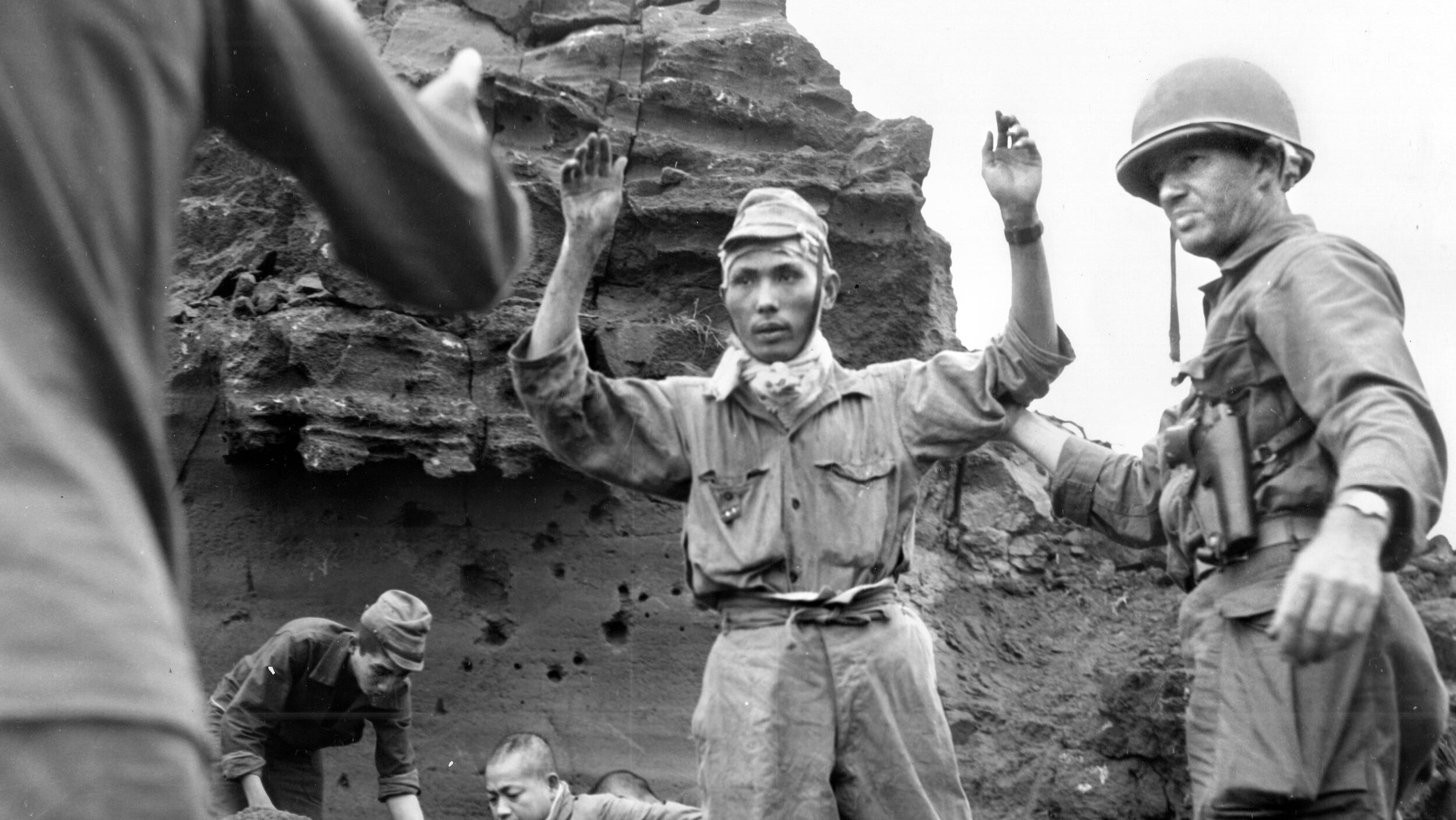

By the end of the campaign, in April 1942, the medical staff was treating thousands of sick and wounded men while being bombed and strafed by the Japanese despite the clear hospital markings on their tents. The nurses even treated wounded Japanese soldiers who had been captured and brought to their hospitals.

So bad did the enemy air attacks become that orders were issued for the medical staff to strap patients to their stretchers and take them to the nearest foxhole when an attack took place.

Losses of doctors and nurses could not be replaced. Two nurses were wounded in these attacks and transferred to the fortified island of Corregidor in Manila Bay for treatment.

On April 8, 1942, all nurses were ordered transferred to Corregidor to avoid captivity when it became clear that the Bataan garrison was about to surrender, but that only postponed the inevitable. On May 6, 1942, Corregidor itself came under ground attack and General Jonathan Wainwright, the American commander in the Philippines, had no choice but to surrender.

Several small groups of nurses had been ordered evacuated by plane and submarine shortly before Corregidor fell, but 67 Army nurses went into captivity with the rest of the American and Filipino forces. They would spend the next three years in a prison camp doing what they could to aid the sick and wounded who shared the camp with them.

The heroic story of the U.S. Army nurses in the Philippines was relayed by newspapers, radio broadcasts, advertisements at home, and eventually a Hollywood movie. Thousands of young women with nursing degrees immediately enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps and the Navy Nurse Corps. Many of these volunteered once again for overseas duty, knowing the risks.

By the end of the war, some 59,000 Army nurses had served. Yet, there were never enough. As late as December 1944, the Army’s Surgeon General raised the manpower ceiling for the Army Nurse Corps to 60,000, a goal that was not reached by war’s end.

The 48th Army Surgical Hospital was one of the first of its kind to go overseas, sailing for Scotland during the summer of 1942. Here, for the first time, the nursing staff received some actual military training, which consisted of marches of five and 10 miles with field packs to toughen them up for expected hardships to come.

During this period the Army also addressed the issue of clothing for the nurses. Clearly the standard white nurses uniform with a lieutenant’s bar on one collar and a medical caduceus with a superimposed “N” on the other would not do for combat conditions. To remedy the situation, the Army provided blue seersucker dresses for nurses in combat theaters but since these would not be adequate in situations of cold, rain, mud, and frigid conditions, long pants were the obvious answer.

But because the Army was sympathetic to the general consensus that women did not wear pants, there was considerable delay before these were officially provided. In the interim, the nurses simply adapted the men’s GI field uniforms or coveralls, as had the nurses on Bataan. Since many of the nurses could sew, the men’s uniforms were adapted to the nurse’s size and shape. Shoes, however, remained a problem, since the Army’s supply came only in men’s sizes.

Having decided that the main effort of the Allied forces would be to defeat Germany first, the U.S. Army and Navy organized their first offensive against that enemy. This was to be an amphibious landing on the coast of North Africa by British and American forces known as Operation Torch.

The Allies’ plan was to land and seize French North Africa as a base for future operations further east. Included within General George S. Patton’s order of battle was the 48th Army Surgical Hospital with 57 Army nurses. It would be the one—and only—time that an Army hospital unit containing nurses was landed on the invasion beaches on D-day.

As it happened, the first American nurses in the European Theater to come under attack were fired upon not by the Germans or Italians, but by the Vichy French. Although it had been hoped that the French would welcome the arrival of the Allies, they opposed the landings with artillery, small-arms and mortar fire, as well as a sortie by ships of the French Navy.

Under this fire, the nurses of the `stood off to the side while the regiments of the 1st Infantry Division went over the side into landing craft for the invasion. Soon, it was their turn. Two nurses were to land together with two medical officers and 20 enlisted men in five landing craft.

Carrying 26-pound packs, helmets, and extra equipment including surgical instruments and bandages, the nurses anxiously climbed down the same nets as the combat infantrymen and into the landing craft. Within minutes they were on the beach. Wet and shivering in the cold November air, the nurses and medical staff soon had a temporary hospital set up in an abandoned home close to the beach. Under sniper fire, they ate their first meal in combat out of a can.

The following morning a soldier brought word that three nurses were urgently needed up front at a battalion aid station. So many casualties had been received there that the staff could not handle the flow and needed help. With two male officers and two enlisted men, three nurses—Lieutenants Ruth Haskell, Edna Atkins, and Marie Kelly––moved to the front. They came under sniper fire as they moved forward until they met a jeep sent to carry them the rest of the way. After a harrowing trip under fire, they reached the aid station on the outskirts of the town of Arzew. Bullets were flying overhead.

The aid station had been a hospital before the invasion. But after being the scene of combat, it was a mess of filth and odors and broken medical equipment. There the nurses found row after row of wounded American and French soldiers needing medical aid. The nurses immediately got to work preparing patients for treatment according to the severity of their wounds. Assisted by an enlisted man, each nurse was given a section of the aid station to work.

One soldier, suddenly realizing that he was being treated by a nurse, cried “Holy cow! An American woman! Where in the world did you come from?” Lieutenant Haskell replied, “Yes, sonny! An American woman, a nurse. And there are more than 50 of us over here to take care of you and your buddies.” Then she rushed the seriously wounded soldier to surgery.

Surgical conditions were miserable. The building had been bombed and all the windows blown out. Lights kept flickering on and off, so most of the surgeries were performed by flashlights held by one nurse while another assisted the doctor. The surgeries went on for hours, and the nurses and aides had to rotate duties so as to not become so fatigued that they could not continue at any one assignment.

Meanwhile, other nurses roamed the halls treating as best they could those awaiting their turn to see a doctor. Hours passed, and rest was a rarity. Finally, after 14 hours, the rest of the 48th Surgical Hospital arrived and took over. Just as the nurses moved to another building to get some sleep, enemy planes came over and bombed the area. The nurses jumped into a nearby trench only to realize that it had been used as a latrine. That was the 48th Surgical Hospital’s introduction to combat.

The French soon surrendered, and most joined the Allied forces. The battlefields moved east and so did the U.S. Army nurses. Romance blossomed between some of the American soldiers and the nurses. Some marriages would result, both in North Africa and later battlefields. Initially, if a nurse married, she would be dishonorably discharged, the same if she became pregnant. However, this policy soon changed, and marriages were permitted although husband and wife were not allowed to serve together. Unmarried nurses who became pregnant were given dishonorable discharges, a punishment usually reserved for convicted criminals; married nurses were given honorable discharges. So sensitive was this subject that the Army did not use the word “pregnant” when issuing the discharge, using instead “cyesis.”

During the German counterattack at Kasserine Pass in mid-February 1943, the American medical units were ordered to retreat to avoid being overtaken by the advancing enemy. The staff, including the nurses, had to hurriedly pack up the hospital and the patients and move 40 miles to the rear, where the 9th Evacuation Hospital took them in.

No sooner had they arrived than the entire group was ordered another 30 miles to the rear. Nurses and corpsmen worked 14-hour shifts to accommodate the new influx of wounded from the fierce battles around Faid Pass and Kasserine Pass, and so close did the enemy come that part of the 48th Surgical Hospital had to be evacuated in a rush, escorted by Sherman tanks.

The German counterattack at Kasserine was their last in North Africa. The Allies resumed their advance, and the supporting medical services moved with them. By this time the medical staff had so much experience that everyone worked without comment. Incoming patients were triaged, sent to either the temporary wards or directly to surgery. Enlisted male personnel transported the patients, worked the vehicles, prepared the food, and erected the tents as the medical units were constantly on the move.

By the end of the North African campaign, the veteran medical units had a rhythm all their own. Studies of their success led to several changes, including name changes. The 48th Surgical Hospital, for example, became the 128th Evacuation Hospital. Personnel, including nurses, who showed potential and had experience were transferred to newly arriving units to share that experience.

The next campaign was Operation Husky—the invasion of Sicily. This time no nurses landed with the assault waves. The 95th Evacuation Hospital came ashore three days after the invasion and prepared to receive patients near the town of Gela.

Much like North Africa, German planes bombed and strafed nearby and the medical staff slept in foxholes. Soon battle casualties and sick soldiers were coming in on a regular basis.

The 95th was augmented by the 59th Evacuation Hospital and the 128th (formerly the 48th) Evacuation Hospital. Here the medical staffs encountered a new danger: malaria. Many doctors, nurses, and corpsmen came down with the disease and were forced to become patients themselves. As a result, the hospitals became critically shorthanded, and many staff voluntarily worked as best as they could despite their own illnesses.

Some of the staff, including the nurses, lost significant weight, suffered from dysentery and other ailments, but nevertheless carried on with the necessary work of treating the injured and ill.

Nurses were also witnesses to one of the more outrageous episodes of the war when General George S. Patton, commanding the Seventh U.S. Army, visited the 93rd Evacuation Hospital located near San Stefano and slapped an injured soldier being treated there. Lieutenant Vera Sheaffer from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania later wrote, “If that had been one of my patients General Patton slapped, I would have hit Patton myself. Believe me, most of the nurses felt the same way.”

Next on the Allied agenda was Italy itself. While British and Canadian forces landed at the “heel” at Taranto, General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army made an amphibious landing at the town of Salerno. The Germans expected a landing and made preparations to repel it.

Sailing behind the assault troops were the 16th and 95th Evacuation Hospitals and the 2nd Auxiliary Surgical Group. A week before the landings these three groups boarded the steamer SS Duchess of Bedfordfor transportation to the Salerno beachhead on August 31, 1943. They were in support of the VI Corps and the 36th (Texas) Infantry Division on the beachhead.

The British captain of the Duchess of Bedford objected to having women, whether they were Army nurses or not, aboard his ship. He spent two days trying to convince higher headquarters to transfer the hospitals to another ship, citing that, as a flagship for the invasion, his would be a prime target of enemy planes and shore batteries.

Eventually he won his argument, and the three medical units were transferred to the U.S. Army Hospital Ship Acadia, afully equipped floating hospital. The nurses were delighted with their new accommodations. They sailed in the well-marked ship to Bizerte, where they had a brief layover as the Salerno beachhead was being established.

Once the Allies had secured the beachhead, the nurses of the 95th Evacuation Hospital were ordered to board the HMHS Newfoundland,a British hospital ship, for transportation to Salerno where the rest of the hospital had already landed. The nurses, now properly attired in herringbone twill coveralls, helmets, and full field packs, boarded the ship at Tunis.

Clearly marked as a hospital ship, the Newfoundland sailed for Salerno while the American nurses became acquainted with the 16 British nurses aboard the ship. The voyage was uneventful, and the two groups became friends as they sailed together.

On Sunday, September 12, 1943, the ship arrived off Paestum in the Gulf of Salerno. It joined with two other British hospital ships, the HMHC St. David and the HMHC St. Andrew, preparing to receive casualties from the beachhead. From the top deck of the ship, the nurses watched as German shore batteries fired at the Allied ships around them and German planes circled the beachhead. Occasionally shells flew past the Newfoundland.

Then a German plane released a bomb that fell within yards of the hospital ship. One nurse remembered, “We looked up and saw a German plane heading for Paestum. The damned fool had dropped a bomb and nearly hit us by mistake. We all had a lot to say about what poor shots the Germans were.” They would soon have cause to revise their opinion.

Higher authority decided that the situation was not yet right to land the nurses, and so the three hospital ships were ordered out to sea for the night. During the night, the three ships had all lights on with clearly defined Red Cross markings in accordance with the Geneva and Hague Conventions. There were no other Allied ships within 20 miles of them. The nurses expected to be landed the following day. That night they celebrated the birthday of one of their own. After the festivities the nurses and crew went to bed, many choosing to sleep on deck to catch the sea breeze.

At 5 am some of the nurses woke up to a strange sound. They soon realized that a bomb had exploded nearby. Fifteen minutes later another explosion was heard, this one rocking the Newfoundland. The hospital ship had been bombed. Many among the crew and medical staff were killed or injured. At first, most could not believe that they were being deliberately targeted. After all, the ship was clearly a hospital ship and as such considered a noncombatant, not subject to attack.

Nevertheless, water was soon flooding the nurses’ quarters below decks, and crew and other personnel were racing around trying to save the ship. Doors were dogged shut, trapping people below decks. Cries came telling of fire below decks. Black smoke began to fill the passageways.

When the nurses of the 16th Evacuation Hospital, also on board, reached their lifeboat stations, they found that the lifeboats had already been lowered away. They crossed over to the other side of the ship hoping to find other boats.

Seeing the situation, the St. Andrew sent over its own boats to assist. Nurses of the 95th Evacuation Hospital managed to lower some boats and make their way to the other ships. One of the British nurses was trapped in a burning cabin; she was one of six who died in the tragedy.

The American nurses were fortunate in that none were killed. Several were injured with broken bones, wounded by bomb fragments, smoke inhalation, and other injuries, and were taken back to Bizerte by the St. Andrew.

“I’ll never forget our first trip to the hospital mess hall,” remembered one survivor. “We looked like drowned rats! We were dressed in whatever clothes we could borrow or were fortunate enough to save from the Newfoundland. We looked awful! But not one person asked us a thing about the sinking.”

The wounded and injured were treated at the 74th Evacuation Hospital in Mateur, Tunisia. The nurses of the 95th were replaced by those of the 93rd Evacuation Hospital at Salerno.

U.S. Army nurses served throughout the Italian campaign. In addition to the danger from accidental bombings, shelling, and snipers, the weather also produced hardships. The 16th Evacuation Hospital was enjoying a rare quiet day near Paestum on September 28, 1943, when suddenly gale force winds struck the area. Within minutes the tents were down, patients exposed to high winds and rain, and freezing hailstones began to fall.

One nurse was in the operating room with a patient undergoing an appendectomy when the windstorm hit. The doctor had already made his first incision when the tent began to vibrate and pull at the tent pegs holding it down. The surgeon made the decision to immediately transfer the patient to the nearby 95th Evacuation Hospital to complete the surgery. The nurses and corpsmen covered the patient in sterile sheets and rushed him to a waiting ambulance. Within moments the 16th Evacuation Hospital was out of business. Nurses from the 8th Evacuation Hospital took over while those of the 16th restored their own facilities.

The war continued in Italy for two more years, with American nurses serving throughout. At Anzio on January 23, 1944, another hospital ship was sunk with American nurses aboard. The HCMC St. David, with the 2nd Auxiliary Surgical Group Team Number 4 aboard, had already been bombed at Anzio, but the Germans had narrowly missed.

Throughout that attack the American surgical team had continued operating on wounded men in the ship’s operating room. As usual, the St. David sailed out to sea that evening, fully lighted and clearly marked. The American surgical team had the night off and were awakened for their next shift at midnight. The rough waters caused seasickness, but the team operated without a break.

At noon, as the ship moved closer to shore, the rough seas prevented any wounded from being transferred to it. Again, that evening the ship sailed out to sea, and with no new patients the crew and medical personnel looked forward to an easy night. At 8 pm a loud explosion announced that a German plane had bombed the ship. The American nurses, some of whom had survived the Newfoundland sinking, had kept their survival equipment handy. Grabbing this gear, they moved up to the top deck and eventually abandoned ship. One of the American doctors was killed in the sinking. The survivors floated for over two hours in frigid waters before another hospital ship came upon them.

Ashore at Anzio three American nurses were looking to report to the 95th Evacuation Hospital in the beachhead after being dropped off by a rattled truck driver. As they walked, they saw British and American troops crawling forward. Lieutenant Hazel Glidewell called out to the soldiers, inquiring how to get to the 95th Evacuation Hospital. A sergeant looked at them in disbelief. “What in hell are you women doing here? We’re the front line, and you’re in front of us. That puts you in no-man’s-land.” The nurses were quickly hustled safely to the hospital in the rear.

Three medical units set up at Anzio. The 56th, 93rd, and 95th Evacuation Hospitals soon decided to set up together to make it easier to handle overflows of wounded, which often occurred. The site was three miles east of Nettuno on a flat stretch of beach. The hospital was completely in the open and well marked. So crowded was the beachhead that there was no other suitable area available.

And no place on the beachhead was out of range of the heavy German artillery. As a result, the hospitals would spend the next three months under intermittent bombing and shelling. Many medical personnel, including nurses, were killed or wounded during these months. Lieutenant and Chief Nurse Blanche Sigman and assistant Chief Nurse Lieutenant Carrie T. Sheetz were killed in these bombings. Lieutenant Marjorie G. Morrow was mortally wounded. Ironically, all three had survived the sinking of the Newfoundland. Nor were the Germans finished with the American nurses.

Because the 95th Evacuation Hospital was hors de combat, the 33rd Field Hospital moved up to replace them. On the very day it arrived and set up, German artillery fire hit the area and killed Chief Nurse 1st Lt. Gertrude Spelhaug and 2nd Lt. LaVerne Farquar. Urged to seek cover in foxholes, the nurses replied, “There is not a single one of us who will let this shelling of hospitals chase us off the beach. We are here to stay.”

The medical facilities at Anzio continued to come under both deliberate and accidental enemy attack. On February 10, 1944, shells fell into the crowded tents of the 33rd Field Hospital, killing one nurse and wounding several other personnel.

To lessen somewhat the likelihood of hospital patients and caregivers being killed or wounded by flying shrapnel, shallow rectangular pits were dug as far down as the high water table would allow. The tents were erected in these pits and walls of sandbags were used to build revetments and blast shields around the tents. This helped reduce casualties within the hospital areas, except for direct hits and antipersonnel butterfly bombs bursting above them.

The nurses stayed at their stations, and three of them—1st Lt. Mary L. Robert and 2nd Lts. Elaine A. Roe and Rita V. Rourke—were awarded Silver Stars.

Dozens of medical evacuation hospitals served in France and Germany as well. One such unit, the 44th Evacuation Hospital, had as its head nurse 1st Lt. Martha Nash. A veteran of the North African campaign, and with a sister who was listed as missing in action while an Army nurse in the Philippines, Lieutenant Nash was determined that her nurses would be as prepared as possible for the coming campaigns. She obtained proper uniforms for them while in England and insisted that they take classes in setting up tents, aircraft identification, map reading, and caring for wounded while under air or artillery attacks. The 44th Evacuation Hospital landed on Omaha Beach on D+13 and went right to work.

During the invasion of southern France in August 1944, Captain Evelyn E. Swanson, the chief nurse of the 95th Evacuation Hospital, was the first Army nurse to land. She had replaced Lieutenant Blanche Sigman, who had been killed at Anzio. Like the men they supported, the U.S. Army Nurse Corps absorbed its casualties and continued on.

The 11th Field Hospital followed close behind the 95th. The 11th was divided into three units, or platoons. Two were 120-bed hospitals and one was a 160-bed hospital. Each of these platoons was highly mobile because of the smaller size and were designed to leapfrog the others as the front moved forward. Each included six nurses whose main duties were post-operative care.

Each member of the American medical corps, as well as the frontline soldiers, were required to wear on their sleeves an American flag to prevent them being taken for Germans by the French Forces of the Interior (FFI), whose guerrilla groups were prone to shoot anyone not instantly recognized as friendly.

As did their buddies in Italy, the U.S. Army nurses in Western Europe fought their way across that continent, one campaign after another. Like their predecessors in North Africa, when the Germans launched their massive winter offensive, the Battle of the Bulge, U.S. Army nurses found themselves retreating with hundreds of wounded patients to care for while under enemy fire. The 12th Evacuation Hospital moved thousands of patients by railroad and air.

The 47th Field Hospital had an even closer call. Assured by the 2nd Infantry Division that strange lights and noises near them were nothing to worry about, they remained near Butgenbach until their commander noticed streams of American vehicles moving to the rear. Now suspicious, he ordered his unit to the rear, passing through Malmédy shortly before the infamous massacre of American soldiers took place there. One group of nurses was twice strafed by enemy aircraft during the retreat.

Another platoon of nurses from the 47th Field Hospital was captured momentarily. Stationed at Waimes, they hitchhiked with the 180th Medical Battalion during the withdrawal until two armed Germans dressed in American uniforms captured the group. While being held, the nurses continued to care for the 36 wounded men. Eventually the group was recovered by other American combat units.

Nearby, the 103rd Evacuation Hospital moved up as close as possible to be available when American forces relieved surrounded Bastogne. The hospital had to double its 400-bed capacity to accommodate the overflow.

One nurse caught up in the battle remembered, “The roads were cut off ahead, and our hospital acted as a battalion aid station for some 6,000 patients. We treated and evacuated as quickly as possible until we got them all out. Then we got ourselves and [the] equipment out. As transportation was at a premium, we left our bedrolls, clothing, and even our Christmas packages with orders that they be burned if the Germans reached the hospital.”

By far the worst duty the U.S. Army nurse in Europe had to endure, once Germany had been overrun, was to try and save as many lives as possible from the Nazi concentration camps. From treating American boys wounded or sick or frostbitten, they now turned to saving inmates who were no more than skin and bones, suffering from typhus, dysentery, and a host of other diseases. Starvation was common to all.

Some, who had been in camps that the Germans tried to destroy lest the Allies find evidence of atrocities, suffered from burns, stab wounds, and gunshot wounds. Lieutenant Helen Richert recalled, “Bodies were still burning. I felt a dark cloud around me for a long time after that.” Lieutenant Francis A. “Frenchie” Miernicke said, “We had no idea what we would see there before we arrived, no warning.”

The end of the war in Europe, V-E Day, did not end the work of the Army Nurse Corps. There were still many thousands of people needing medical care. The 166th General Hospital was converted into a hospital to care for prisoners of war.

Lieutenant Kay Yarabinec remembered, “The reason was that most Germans ran away from the approaching Russian lines into American lines to surrender. We had to teach them how to care for their own, because medicine had fallen far behind that of other Western countries. This was due to the fact that their best physicians and scientists had either fled from Germany or been killed in concentration camps.”

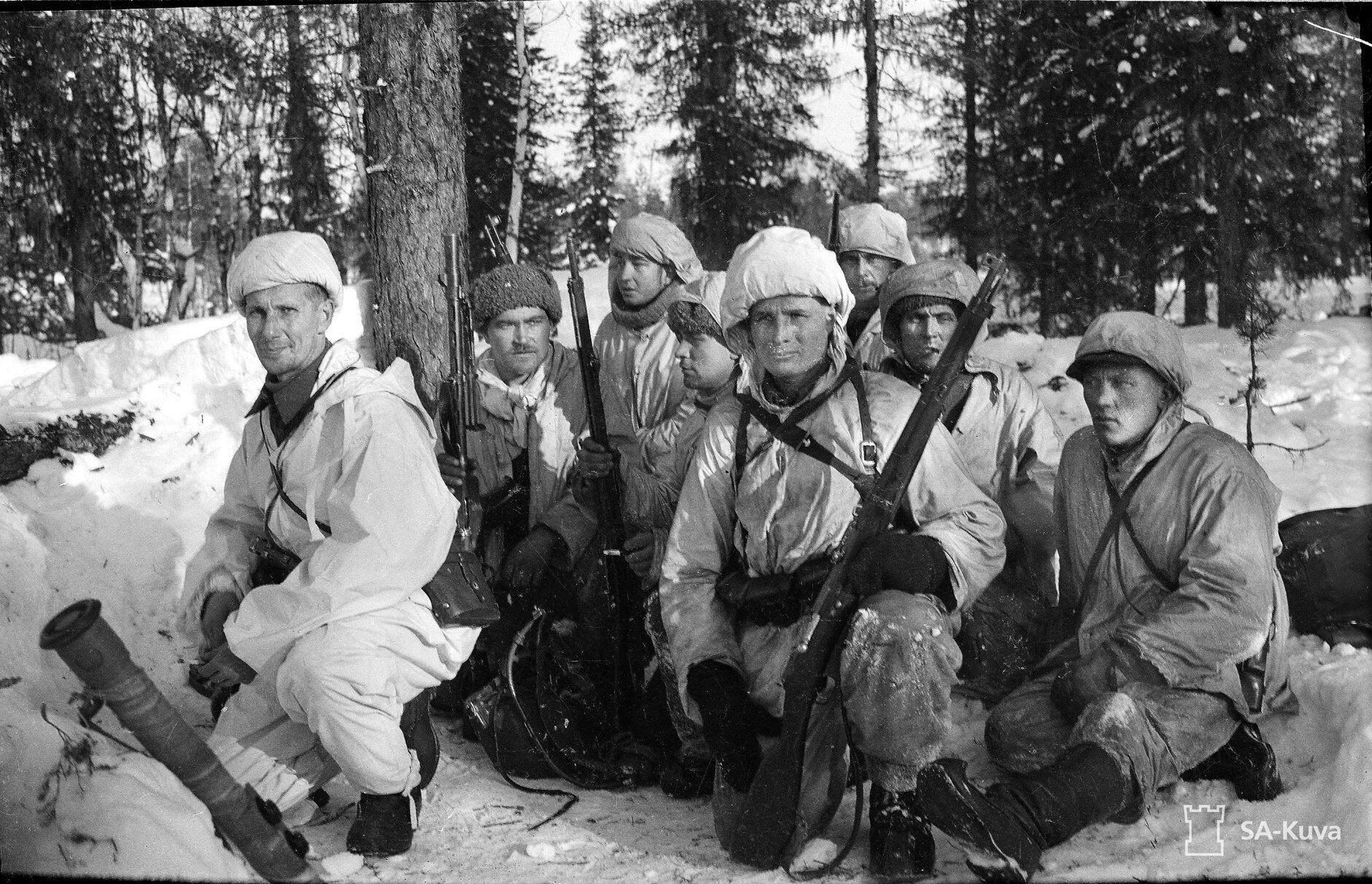

Although V-E Day ended the war in Europe, the war against Japan was still raging. The Army Nurse Corps served throughout the Pacific campaigns, following General Douglas MacArthur’s difficult struggle up the coast of New Guinea in the South Pacific and across the Central Pacific Theater of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. The farthest battlefields in which the nurses served were in the China-Burma-India Theater under General Joseph W. Stilwell. Ninety Army nurses of the 159th Station Hospital arrived in India in mid-1942. This totally new environment and culture came as a bit of a shock, but as always the American nurses quickly adapted. Breakfast consisted only of coffee and bread. Water was strictly rationed. Servants, however, were plentiful.

The 159th Station Hospital, later expanded into the 181st General Hospital, soon found itself treating British, Chinese, and native troops. Sleeping under mosquito nets and living in native huts, or bashas, the personnel fought off the ants, sand, mice, rats, flying roaches, and snakes, performing their duties without pause.

The vast distances in Burma, China, India, and the Pacific gave Army nurses another dangerous duty. To get the most serious cases to more sophisticated treatment facilities as quickly as possible, the Army Medical Corps had established the Medical Air Evacuation Squadrons (MAES), conducted by the Army Air Forces.

Seriously ill and wounded patients were flown out of the combat zone as soon as possible in Douglas C-47 Skytrain aircraft staffed with medical corpsmen and specially trained flight nurses. These women attended a special training course at Bowman Field near Louisville, Kentucky, and were then sent to the forward areas. Each plane held 18 litters, nine per side. There were no doctors on these flights, leaving the full responsibility for medical treatment and decisions to the flight nurse.

These nurses flew all over the Pacific and the CBI Theaters performing their jobs. One of them, 1st Lt. Anne M. Baroniak, received the Distinguished Flying Cross for a record of over 300 flights with the MAES, and many other nurses were awarded the Air Medal.

Another flight nurse, 2nd Lt. Jeanette C. “Tex” Gleason, had the rather unique distinction of being the first flight nurse to bail out of an aircraft in China. She landed 50 miles from Kweilin with only minor bruises but wandered in the mountains for four days before friendly locals took her in and guided her to safety.

The segregated U.S. Army of World War II also segregated its medical treatment facilities. As a result, the Army Nurse Corps accepted African American nurses into segregated units and deployed them overseas and at home. Up until the war, the Army had refused to accept African American nurses. But the outbreak of war brought pressure from various groups to allow them to serve, and soon African American medical units, including African American nurses, were serving at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Camp Livingston, Louisiana.

Many would later serve overseas in North Africa, Italy, Europe, and the Pacific, usually where African American combat or service units were stationed. They often were assigned to treating enemy prisoners of war. About 500 African American nurses served in the Army during World War II.

Another overlooked group was the male nurse, much more prevalent at the time than later. Male nurses were upset that, when drafted, barely 40 percent of them were assigned to medical units, thereby wasting their civilian skills. They were not allowed to join the Army Nurse Corps and thereby gain commissioned rank.

H. Richard Musser, R.N., wrote, “Men nurses throughout the country feel that they are being [sic] a great injustice in that they are not rated as women nurses are.” But nothing was done about this inequity, and male nurses continued to serve as enlisted personnel and were often assigned menial duties far below their professional skill level.

In the Pacific, the war went on. The 38th Field Hospital moved to Kwajalein a few months after the Marines and Army troops had seized the atoll. There, while treating natives who had lived through the invasion, they encountered an unusual problem. Lieutenant Hannah M. Matthews reported, “When the natives were brought into our hospital, they refused to stay in our beds, but slept on the floor under the beds.”

To the south, at Hollandia, New Guinea, Lieutenant Evelyn Langmuir was surprised to find comfortable quarters in the jungle, complete with a post exchange and Coke machine.

On Saipan, the 369th Station Hospital did not have it quite so luxurious. Water was in short supply. Rainwater was used for bathing. Only a few patients each day could be bathed, while others had only their faces and hands washed. Civilians who had suffered under the occupying Japanese,were often the worst cases. Aided by the 148th Station Hospital, the nurses treated more than 20,000 cases of dengue fever.

Danger existed in holdout Japanese soldiers who came out of the jungle at night to steal food and supplies and take the occasional shot at any American uniform they saw.

Saipan also received thousands of casualties from the Battle of Iwo Jima. Teams were organized to administer plasma and whole blood to the many shock cases from that battle. The 369th Station Hospital’s 83 nurses found themselves caring for 1,342 patients.

As if that was not overwhelming enough, an epidemic of food poisoning knocked out so many nurses and other medical staff that Military Police had to be called in and instructed on how to care for the wounded while the medical staff recovered. Other hospitals on Guam and Tinian were also used to handle the overflow of wounded.

Even the Chief Nurse of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps in the South Pacific, Lt. Col. Nola G. Forrest, served in the combat zone, arriving on the Philippine island of Leyte with the forward groups of nurses from the 1st and 2nd Field Hospitals.

Their arrival was greeted by a typhoon that shook their transport from side to side and a couple of Japanese aircraft that attempted to bomb and strafe their ship.

Both groups of nurses set up temporary quarters at the 36th Field Hospital and soon were dealing with more than 600 patients. Later, a few nurses actually treated the Bataan nurses who had finally been rescued after three years of captivity on Luzon.

U.S. Army nurses served from the first day of the war to the last. Some of their last casualties were due to another attack on a hospital ship. The USHS Comfort was lying off Okinawa on April 28, 1945, preparing to sail to Saipan with a load of casualties, when a Japanese plane made its appearance.

The kamikaze dived on the well-lighted target and crashed into the superstructure, the force of impact hurling the plane’s motor through the deck into the surgery area. Oxygen tanks immediately began exploding. First Lieutenant Gladys C. Trostrail of the Army Nurse Corps was tossed across the room, through the bulkhead, and found herself regaining consciousness while trying to avoid drowning from water pouring down from broken pipes. An enlisted man pulled her to safety.

In the next ward, 2nd Lt. Valerie A. Goodman was preparing penicillin injections with another nurse when she suddenly found herself trapped beneath a metal cabinet, blown over by the force of the explosions; the nurse next to her was killed.

In all, one Navy and four Army medical officers, six Army nurses, one Navy and eight Army enlisted men, and seven patients were killed by the kamikaze. Another 10 patients, seven sailors, and 31 soldiers, including four nurses, were wounded.

Nor did it end there. Ashore on Okinawa 10 field hospitals were caring for the wounded and sick soldiers, sailors, and Marines. On May 3, 1945, the 68th Field Hospital was hit by “friendly” naval artillery that wounded several patients and staff.

By the end of the war, 201 Army nurses had died while on duty, 16 of them from enemy action; dozens of others had been wounded. Some 1,600 earned decorations for meritorious service.

By September 30, 1946, only 8,500 Army nurses remained on duty, the others having decided to return to civilian life. Many married and raised families. Nearly all remained in the nursing profession. Their service had convinced the U.S. Army that it needed a permanent Nurse Corps, and in 1947, Congress created the permanent Nurse Corps in the Medical Department of the Regular Army.

They also granted their nurses permanent commissioned officer status. On June 19, 1947, Colonel Florence Blanchfield was given Army Serial Number N-1 and commissioned as a lieutenant colonel, a permanent commission in the U.S. Army.

The U.S. Army nurse was here to stay.

Great story! We indeed owe these angels of mercy quite a debt.