By George T. Raach

For the hard-pressed German Empire, New Year’s Day 1918 brought a compendium of evils. The Allied naval blockade, increasingly effective, depressed industrial production and stoked a war weariness made manifest in strikes and bread riots. Manpower reserves were dwindling; those called to the imperial colors were often in their middle teens. It seemed likely that one or more of Germany’s allies would soon seek a separate peace. And worst of all, the United States was now in the war on the side of the Allies, the first of its large, fresh divisions already in France.

The only bright spot in the German gloom was the prospective peace with Russia, a move that already had begun to free up some 44 German divisions for use on the Western Front. These additional units would change the force ratio from 3:2 in favor of the Allies to 4:3 in favor of the Germans, thus making possible a series of last-ditch spring offensives. General Erich Ludendorff, acting commander of the German Army, believed it imperative to use these divisions quickly and decisively. Unless this was done, he warned in a year-end letter, increasing numbers of robust American forces would make it impossible for Germany to achieve complete victory or even a satisfactory negotiated peace that enabled the Kaiser to keep some of his territorial acquisitions.

It was a desperate prognosis, but Ludendorff’s assessment had merit, and in March and April 1918, the German Army launched two major offensives—Operation Michael and Operation Georgette. These new offensives met with only limited success against British and French forces in northern sectors of the Western Front, partly because of the unexpectedly strong defense put up by the Allies, partly because there were no reserves immediately available to exploit or sustain initial German gains.

On May 27, Ludendorff initiated a third offensive, Operation Blucher-Yorck, with the intent to drive a salient into the Allied lines from Soissons and Rheims to Chateau-Thierry and force the Allies to commit their reserves. Then, depending on the tactical situation, German armies could either cross the Marne at Chateau-Thierry and continue their attack southwest toward Paris or attack again in the north over the old Somme battlefield.

The German attack burst against four French and three British divisions arrayed on a 25-mile front along the historic road known as the Chemin des Dames. It tore through poorly prepared defensive positions, capturing 60,000 prisoners, 650 artillery pieces, and 2,000 machine guns. Despite the fact that the French committed almost all of their reserves, including 35 infantry and six cavalry divisions, the attack surged ahead. Crossing the Aisne River on the first day, German forces captured Soissons on May 29 and drove relentlessly south toward Chateau-Thierry. A breakthrough seemed likely to open the road to Paris.

The town of Chateau-Thierry, 53 miles northeast of Paris, was a French transportation hub of 7,000 people. It straddled the Marne River, which at this point was between 150 and 225 feet wide and up to 15 feet deep. A large island created by the Marne and a canal on the south dominated the waterfront. Houses and small factories dotted the island’s eastern end, while at the western end there was a wooded park. The town and the surrounding area had been outside the active war zone since the autumn of 1914. Buildings were still intact and fields cultivated.

On the north bank, formidable bluffs rose 450 feet above the river. The chateau from which the town took its name was located on the lower portion of the bluffs and was occupied by a small French garrison. Proceeding southeast from the chateau, the Rue Carnot crossed the Marne via a stone span known as the West Bridge. It then passed over the island and canal and entered a large, circular plaza, the Place Carnot, before continuing south across a broad plain.

Parallel to the river on the north bank was a road leading from the village of Brasles to the east. It ran into the Quay, an oblong plaza adjacent to the West Bridge, before crossing the Rue Carnot and continuing south. A similar road paralleled the river on the south bank, running from the village of Crezancy to the Place Carnot. Two smaller roads led north. The one to the east ran through a grove of trees to the Marne, while the road to the west ran alongside a railroad spur next to a sugar factory. Both crossed the Marne on the East Bridge, a structure that could accommodate rail cars, wagons, and troops.

The West and the East Bridges, about 1,500 feet apart, were the only Marne crossings for five miles on either side of Chateau-Thierry. Once in German hands, they would permit troops to move freely across the Marne and be resupplied via the extensive Marne rail system, avoiding the logistical problems that had forced Ludendorff to abandon his first two offensives. The French Army lacked the ability to prevent such a crossing on its own.

On May 30, the Germans occupied the bluffs north of Chateau-Thierry, 40 miles from their starting point, and sent patrols into the city. French resistance was far from stiff. The 10th Colonial Division, composed of Senegalese and other African troops and a smattering of disparate and disorganized French units, had managed to establish only a few hastily prepared, vulnerable positions. The bridges appeared well within German grasp.

At the end of his resources, French Army Chief of Staff Henri Pétain sought assistance from General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Heretofore, Pershing had been prickly about allowing American troops to serve under French command, but this was an emergency. He immediately placed the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions under French control. American divisions were organized with two infantry brigades of two regiments each, a three-regiment artillery brigade, an engineer regiment, a machine gun (MG) battalion, and various supporting units. They had an authorized strength of 28,059 personnel, 6,638 horses and mules, and more firepower than existing Allied or German divisions.

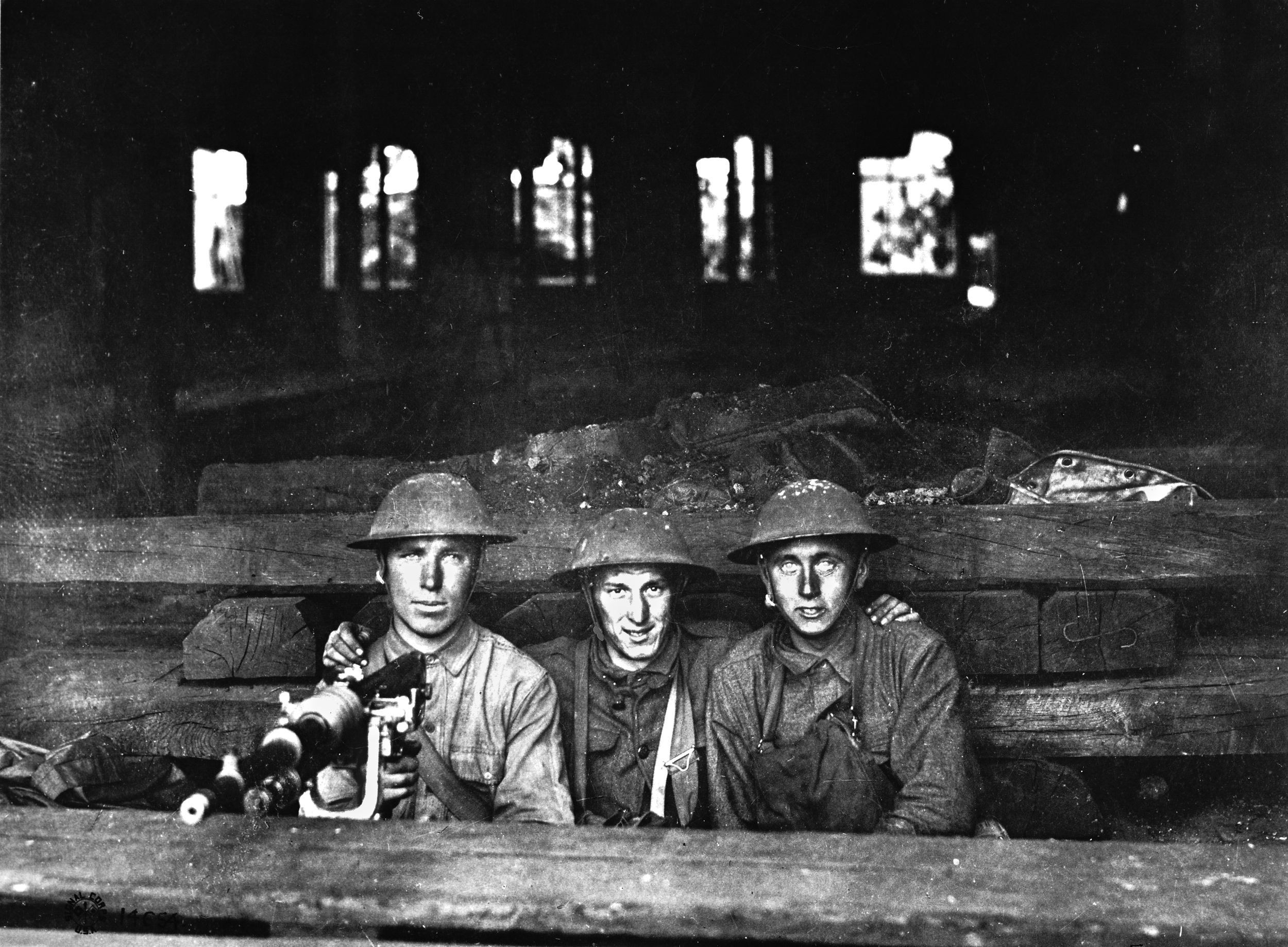

The 7th was the 3rd Division’s machine-gun battalion. Originally organized with four companies comprised of soldiers levied from the division’s infantry regiments, the battalion had been reduced to two companies in January 1918 and designated a motorized unit to give it the ability—theoretically—to rapidly reinforce infantry brigades. However, no trucks were issued before the battalion left the United States in April. In fact, the battalion had received neither its vehicles nor its full complement of Hotchkiss machine guns until May 24, when 52 Ford Model T half-ton trucks, six touring cars, and 24 Indian motorcycles arrived. In an era when few men had either driven motor vehicles or fired machine guns, there was much training to do and little time in which to do it.

When Maj. Gen. Joseph Dickman, commanding general of the 3rd Infantry Division, received Pershing’s order, he immediately directed his division to prepare to move to the vicinity of Chateau-Thierry to reinforce French forces fighting in the area. With little organic support, the division was dependent on rail to move the bulk of its troops, horses, equipment, and supplies. The only unit with the wherewithal to move immediately was the motorized 7th MG Battalion. At 10:30 on the morning of May 30, Dickman ordered the 7th to Conde-en-Brie, a town located seven miles southeast of Chateau-Thierry. There, Major Edward G. Taylor, the battalion commander, was told to place his unit at the disposal of the senior French officer.

By mid-afternoon, the 7th had loaded its Fords and begun its march. Each section had two vehicles: one for the gun, its three-man crew, and part of the 2,500 round basic load of ammunition, the other for the remainder of the section’s personnel and ammunition. All vehicles carried an extra five gallon can of gasoline. Touring cars carried officers and headquarters personnel, while the motorcycles were used by NCOs, messengers, and guides. The division provided eight three-ton trucks to carry gasoline and additional supplies.

On the move, badly rutted roads choked with retreating soldiers and refugees limited the 7th‘s progress. Several times the battalion halted to locate missing fuel trucks and refuel, causing several hours’ delay. Soldiers often had to dismount and push the overloaded, underpowered Fords up inclines. Mechanical failures and flat tires were commonplace. When night fell, the battalion pushed on without headlights. The trek seemed endless to the soldiers on small, cramped trucks, but at noon on May 31 the lead elements reached Conde-en-Brie, having averaged five miles per hour for 100 miles.

In the throes of a general retreat, Conde-en-Brie was bedlam. It took Taylor time to find someone with the authority and knowledge to position the battalion. Ultimately, the commander of a retreating French division told Taylor to take his battalion to Chateau-Thierry and support the 10th Colonial Infantry Division, which was still fighting a rearguard action.

Although his vehicles were low on gas, Taylor pushed on rather than waiting to refuel. Early Fords lacked fuel pumps; when fuel was low and hills steep, the engines stalled. Shortly after leaving Conde-en-Brie, the column ground to a halt. Crews hurriedly dismounted and lugged guns, tripods, and a limited supply of ammunition four miles to the hamlet of Nesles-le-Montagne, south of Chateau-Thierry. Gas tanks of some sputtering Fords were drained to put fuel into others, allowing more troops and ammunition to come forward during the night.

At Nesles, Taylor found that the battalion had all of its guns but only about half of its soldiers. Most had not slept for nearly 36 hours or eaten since breakfast the day before. While they formed into marching order for the descent into Chateau-Thierry, nearby French batteries began to fire at Germans in the hills north of the Marne.

Taylor remained in Nesles to sort out arriving forces, sending Captain Charles Houghton, the A Company commander, into the town. At the West Bridge, Houghton found the commander of the retreating 10th Colonial Division, who told him to place his guns on the south bank and cover the French withdrawal. The battalion began to deploy on a 992-foot front. Taylor positioned his two companies to cover the approaches to the bridges and the streets on the north bank. He assigned A Company the island, the left half of the battalion sector. On the right, B Company occupied the sugar refinery and other nearby structures. Fires of the two companies were tied into the West Bridge, where the French had placed four additional machine guns. The companies were to cover the bridges and the French engineers who were planting demolition charges on them, prevent a German crossing of the Marne, and protect the left and right flanks of the battalion, which were in the air.

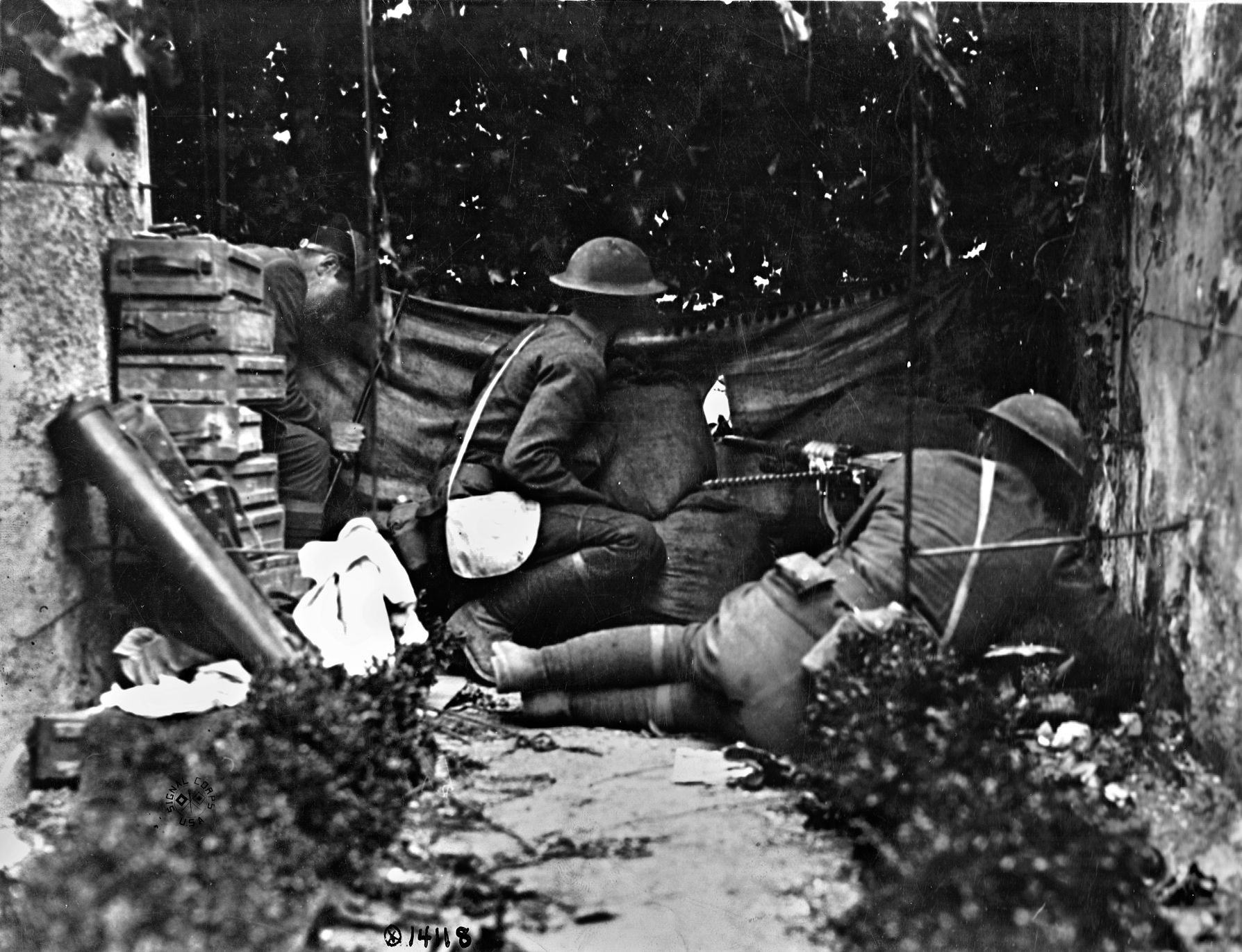

A Company deployed along the river using woods, houses and garden walls for cover. B Company covered the East Bridge with two platoons facing north across the Marne and one deployed farther east across the Crezancy Road to protect the right flank. Not all guns were in place by the time darkness fell, and during the night officers and NCOs placed the remainder, adjusting their positions at first light.

The French commander ordered Houghton to send two machine guns north of the Marne to support a small French rearguard detachment. Houghton selected Lieutenant John T. Bissell, West Point class of 1917. Bissell took 12 men and two guns from A Company across the river that evening. Once on the far bank, he led his small force up the Rue Carnot to the foot of the hill in front of the chateau, then northeast to an old watchtower at the intersection of four streets. Near the tower, he placed one gun facing north to engage Germans descending the bluffs and the other to the east to fire down the Brasles Road. The French troops kept one Hotchkiss in reserve. Later that night, the French pushed their line farther east and placed their Hotchkiss to cover the right flank, allowing Bissell to move his second gun to the north, where he paired it with the other. The battalion spent the night improving its positions under occasional artillery fire. To keep the Germans from learning their location, the 7th did little firing.

The first streaks of dawn appeared at 3:45 am on June 1. In the B Company sector, Captain John Mendenhall had verified the emplacement of four guns in the sugar refinery under the control of Lieutenant Luther W. Cobbey. This position was well sited to protect the East Bridge and interdict movement on the road entering Chateau-Thierry from Brasles. Another platoon was deployed across the road leading past the sugar factory across the East Bridge, and Lieutenant Paul Taylor Funkhouser’s three-gun platoon was about 200 feet farther east and north of the Crezancy Road facing the Marne.

In the growing light, Funkhouser saw movement across the river on the Brasles Road. Straining his eyes, he made out a column of German infantry advancing in perfect marching order, oblivious to the Americans. He ordered his guns to fire, and shortly Cobbey’s guns also opened on the advancing column. As the guns found the range and the fire became more effective, the Germans rushed into the wheat fields between the river and the road. Regrouping, they began to move in rushes toward the East Bridge. Simultaneously, German artillery began to rain shrapnel and high-explosive shells onto Funkhouser’s positions, forcing him to relocate.

Cobbey’s guns in the sugar refinery were not much bothered by the artillery fire. However, the Germans now had the cover of their own Maxim machine guns sited in buildings directly across the river from the refinery. Despite the enemy’s Maxims, Cobbey, who later received a Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the battle, broke several German attempts to rush the bridge and forced them to keep under cover.

Fighting began along the length of the line, and artillery fire drove some American gunners from the top floors of buildings into positions lower down. Shells also cut the telephone wires on which communications depended, and command and control was limited to runners and personal intervention. Gas shells were intermixed with shrapnel and high explosives, making occupation of shell holes and basements hazardous. Rue Carnot, the resupply route, came under artillery and machine-gun fire, and daylight resupply had to be abandoned.

On the north bank of the Marne, the French infantry continued to resist, although as the day wore on the numerically superior German forces gained the upper hand. French forces began to give ground, and fresh German units massed for a night attack against the bridges. To complicate matters, a rumor reached the defenders that German forces had forced a passage over the Marne at Jaulgonne, five miles east. If true, that force could take B Company in the flank and roll up the battalion, leaving the crossings unguarded. To meet the threat, Mendenhall designated secondary positions for his company farther south where they could enfilade the Crezancy Road.

At dusk on June 1, the end of their first day of combat, A Company had four guns on the west end of the island covering the battalion’s left flank. Two guns were in the center of the company position enfilading streets north of the Marne and the quay adjacent to the West Bridge. The other two guns were placed on the east end of the island to interlock with the B Company guns in the sugar refinery and riverside warehouse. Bissell and his two-gun section remained isolated north of the river. Shortly after dark, the four French guns in A Company’s sector were withdrawn. Houghton replaced them by taking one gun from each platoon and positioning them where they could fire on the quay north of the river.

B Company had Funkhouser’s three guns on the east covering the battalion’s right flank. Cobbey’s four guns remained in the sugar refinery buildings, and the four guns of B Company’s first platoon were located along the Crezancy Road embankment due south to cover the East Bridge. After nightfall, German artillery fire increased.

Early in the evening, the chateau fell to the Germans, and combat intensified as the French fell back across both bridges. At 10 pm, close-range fighting erupted on the quay at the north end of the West Bridge, and German artillery fire shifted to the houses that fronted the Marne on the south bank. Hand-to-hand fighting moved onto the West Bridge, and it appeared that the Germans would soon force a passage. At this point, despite the mob of French and German soldiers intermingled on the bridge, the engineers set off their demolitions. French and German soldiers were hurled through the air, and 50 feet of the bridge fell into the Marne. With the bridge down and the combatants separated, A Company, whose fires had been masked by the fighting on the bridge, opened with devastating effect on the quay. Twice the German infantry massed for another try at the bridge; twice they were repulsed.

The West Bridge was gone, but Bissell and his detachment were still on the north bank. As the French began to withdraw from the northeast part of the city toward the West Bridge, Bissell’s two-gun detachment and a small platoon of Senegalese infantrymen covered them. This was a mixed blessing. Although grateful for the infantry support, Bissell could not communicate with the Senegalese, who spoke unfamiliar tribal languages. Bissell leapfrogged each gun to ensure that at least one could always fire on his pursuers and moved his men slowly toward the West Bridge.

Amid the chaos of ongoing fighting and the cries of the wounded littering the street, Bissell was unprepared for what happened next. A German Maxim suddenly enfiladed the street where Bissell and his men crouched in doorways. It delayed his approach to the bridge, which moments later went up in a sheet of flame.

In the darkness, Bissell’s small detachment, joined by a number of French poilus, worked its way toward the East Bridge along streets swept by both German and American fire. There, he was confronted by the challenge of how to get across in the darkness in the face of B Company’s guns. At first Bissell thought he might be able to swim the river, but the fast current convinced him that it was too risky. Bissell and his runner went to the north end of the bridge where he called to the men on the other side. He was answered by a burst of machine-gun fire. Ducking under cover, he continued to shout across the river until Cobbey appeared, crossed the bridge, and brought in Bissell’s bedraggled force. With a combination of American, French, and Senegalese on the bridge, B Company held its fire, and in the confusion and darkness an unknown number of Germans mingled with them and reached the south bank, where they quickly disappeared.

The situation on the south bank was bewildering. Mendenhall was unsure how many Germans had penetrated his position and whether he could hold them back with the forces at his disposal. He had heard the explosion at the West Bridge but did not know whether the Germans were across in force there. Telephone lines to battalion headquarters, 300 yards to the rear, had been severed, and although Mendenhall sent several runners none returned. Seeking to learn the true situation, he sent more runners to his three platoon leaders, telling the 1st and 2nd Platoons to hold their positions and reorienting the 3rd Platoon toward the right flank. Then he and a runner made their way back to battalion headquarters.

Taylor told Mendenhall that no Germans had made it across the West Bridge. From his perspective, the greatest threat was a German advance across the East Bridge. Mendenhall told Taylor that some Germans had reached the south bank when Bissell returned. Taylor instructed Mendenhall to clear them from his sector and gave him the four guns he had at battalion headquarters together with improvised crews.

Mendenhall returned, traveling across the cultivated fields. When his small force reached the Crezancy Road where he had positioned 1st Platoon, he found no Americans. Looking into the darkness, he saw silhouetted against the night sky the unmistakable shapes of German helmets on the south bank. Clearly the Germans were massing, perhaps for a rush at the rear of the gun positions covering the bridge. Had 1st Platoon remained in position, it could easily have disrupted them. So could 2nd Platoon located in the refinery to the east of the field in which the Germans were gathering, but 2nd Platoon had not fired a shot.

Gathering up his four guns, Mendenhall positioned two of them to fire if the Germans made an attempt to move or if they heard fire from the sugar refinery. Taking the other two guns, he made his way to the refinery, where he found no trace of 2nd Platoon. There were no Germans there, either. Southwest of the refinery were two long, open sheds. Mendenhall quietly placed his guns under the cover of the sheds within 100 yards of the nearest Germans and opened fire. The two guns he left at the original 1st Platoon position opened as well. Surprised by the sudden bursts, the Germans were soon in full flight back across the Marne.

Had the Germans been aware of the true situation—a usable bridge not covered by fire—they would no doubt have crossed in force, and the course of the battle would have changed dramatically. Investigating the whereabouts of his two missing platoons, Mendenhall discovered that his runners, exhausted and with nerves on edge, had delivered the wrong message. Instead of telling the platoon leaders to hold their positions, they had told them to withdraw immediately to the second line.

On June 2, both sides reorganized and resupplied. In the evening, the Germans made an attempt to cross the East Bridge but were repulsed by the coordinated fire of both companies. On the 3rd, the Germans moved more Maxims into Chateau-Thierry and the ensuing machine-gun duels forced the Americans to reposition some weapons. During the afternoon, the battalion was notified that it would be relieved that night. In early evening, German fire increased in intensity, and the Americans responded. By 11 pm, the barrels of some guns glowed cherry red.

The relief was not completed until dawn, and firing continued throughout the night. When the 7th Battalion left the line, some of its guns were so hot that they could not be dismounted from their tripods and instead were exchanged for guns in the relieving force. The 7th Machine Gun Battalion’s defense of Chateau-Thierry had ended.

Although the 7th had made mistakes, it had performed remarkably well in its first combat action, conducting a tactical road march with few maps, inadequate support, and inexperienced drivers on roads choked with the detritus of war. It had entered Chateau-Thierry with no combat experience and with two months less training than AEF regulations required. It had faced tough, combat-experienced adversaries that far outnumbered the battalion in terms of men, machine guns, and artillery. It had fought its battle with little support from the French, who were still reeling from the initial German assault. The greatest compliment paid to the 7th came in an official citation prepared by General Pétain, who said the unit “in the course of violent combat disputed foot by foot with the Germans [and] covered itself with incomparable glory.” If the Germans harbored any doubts about American combat effectiveness, the professionalism of the 7th MG Battalion at Chateau-Thierry did much to dispel them.

This early operation of the American forces validated Pershing’s decision that the American army would fight as a unit rather than being attached to Allied armies. He saw little point in continuing the unsuccessful mass attacks that gained a few meters of ground at the cost of thousands of lives.