By Victor Kamenir

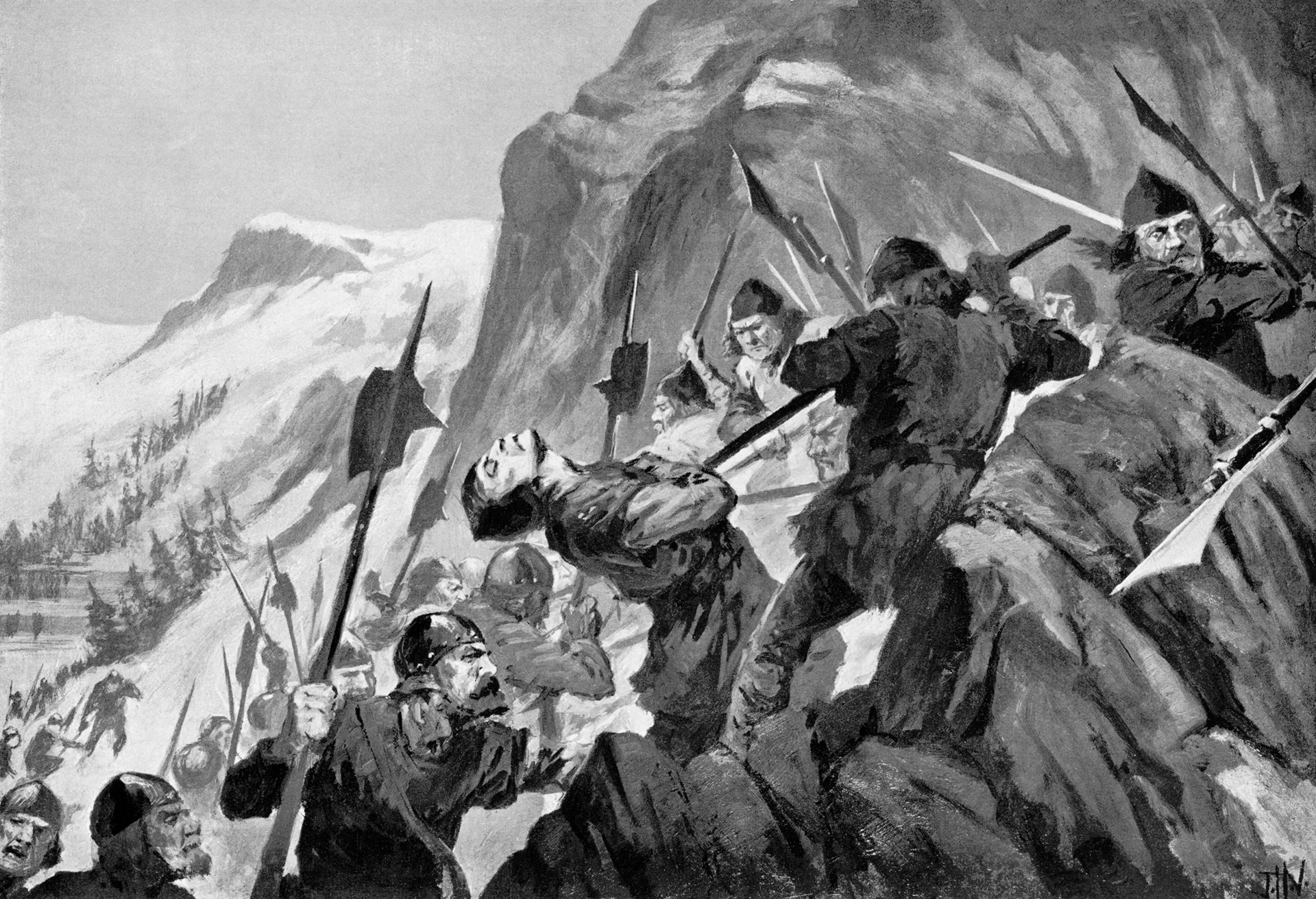

The logs and boulders came tumbling downhill, gaining speed before they reached the bottom of the hillsides in the mountain pass. They knocked down horses and men and even sent some of them tumbling into the lake. Swiss foot soldiers armed with halberds, swords, and flails charged downhill into the tightly packed ranks of Austrian foot and horse. They waded into their stunned foe with a fury born from hatred and resentment. Unable to charge, the Austrian horse was helpless against the furious attack. The dead piled up quickly as the Austrians sought to escape the slaughter. The Swiss were on their way to a stunning victory at Morgarten Mountain that would send shock waves throughout the Holy Roman Empire.

Pope Leo II crowned Charlemagne king of the Lombards and the Franks in Rome on December 25, 800; in so doing, he revived a title not used since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Charlemagne united most of central and western Europe into an empire that at one time encompassed territories of at least 14 modern-day countries. For all intents and purposes, the empire was a multi-ethnic superpower.

In the centuries following Charlemagne’s reign, the empire developed into a decentralized elective monarchy presiding over a system of autonomous kingdoms, duchies, principalities, and free imperial cities. Members of the highest nobility, called prince-electors, elected one of their peers to the title of the King of the Romans; however, only upon coronation by the pope, a practice eventually discontinued in the 16th century, would the king of the Romans become the Holy Roman Emperor.

The elected office of the emperor traditionally was dominated by the German-speaking noble houses of Europe. In this environment, the emperor often had a male relative elected to succeed him after his death. The title was held in conjunction with the titles of king of Germany and king of Italy. Technically, this individual was the “first among equals.” The emperor’s power depended on his ability to form political alliances and gather an army loyal to him.

The lands of the Holy Roman Empire were classified as feudal or allodial. In a feudal arrangement, a noble house held hereditary estates, a fief, from the empire in exchange for allegiance and certain duties, primarily military. The fief provided its lord with the income and resources of the land and labor of peasants bound to it. In contrast, an allodial territory was one for which no feudal contract existed. It was subject to the emperor as sovereign but not to the emperor as overlord. Communities enjoying the allodial status exercised significant control over their own affairs.

While prevalent throughout the rest of Europe, the feudal system did not completely take hold among the fiercely independent free farmers and shepherds of the Swiss highlands. The largely subsistence-level economy of the high mountain districts, or cantons, did not produce sufficient economic surplus to fully support the feudal system of local overlords. Particularly stubborn and independent-minded were the highlanders of the confederated cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden, which collectively were known as the Forest Cantons.

The canton of Schwyz was typically at the forefront in the Swiss struggle for independence and, until modern times, the word “Schwyz” in English was synonymous with “Swiss.” “The Schwyz are completely armed and quite free,” wrote Italian historian Nicolo Machiavelli. “To the lords and gentlemen who live in that region they are entirely hostile, and if by chance any come into their hands, they put them to death as the beginning of corruption and the causes of all evil.”

The Forest Cantons were located in the central part of Switzerland near the southern reaches of Lake Lucerne, a relatively quiet backwater of central Europe. The situation changed drastically in the first half of the 13th century. In the southern portion of the canton of Uri lies the St. Gothard Pass, linking Switzerland with northern Italy. Until the 1220s, the route was navigated only by a treacherous roundabout trail passable only on foot; however, after a wooden bridge was constructed in 1230 to span the Schollenen Gorge above the Reuss River, the roads through the backwater cantons of Uri and Schwyz became strategically important roadways between Germany and Italy.

The movement of goods through the Forest Cantons as a result of increased trade between Germany and Italy in the Late Middle Ages brought a steady income stream into the imperial coffers. To prevent any individual noble house from attempting to grab this important real estate, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of the House of Hohenstaufen (not to be confused with Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg) declared the cantons of Schwyz and Uri as free from Imperial authority in 1240 and 1243, respectively.

Granting the canton of Schwyz allodial status brought Imperial interests into conflict with the House of Hapsburg. Starting from modest beginnings in the northern Switzerland district of Swabia in the modern-day canton of Aargau, by the turn of the 14th century the House of Hapsburg was a major player in imperial politics. While shifting their power base to the duchies of Austria and Styria, which formed the core of the future Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Hapsburgs maintained their extensive landholdings in Switzerland. But they thirsted for more.

Through patronage and proxy, the House of Hapsburg exercised control over multiple properties in the cantons of Unterwalden and Schwyz. To counter the encroachment by the Hapsburgs, representatives from Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden, on August 1, 1291, established a mutual defense pact known as the Everlasting League, or League of the Three Forest Cantons. The purpose of the league was to protect the interests and guarantee the liberties of the three cantons in relation to the Holy Roman Empire. The following year Zurich and Bern allied themselves informally with the league for protection against the Hapsburgs.

The new political entity did not have a single leader and was governed instead by cooperation among various local interests. In defense of their freedom, all able-bodied men were expected to be enrolled in the cantonal militia, organized around old clans. Mountainous terrain and lack of economic resources prevented the effective use of cavalry in the Forest Cantons, leading instead to development of highly motivated and capable militia infantry, which was expected to train regularly and provide its own weapons.

Since the death of Conrad IV in 1254, no Holy Roman Emperor was crowned for almost 20 years, a period called the Great Interregnum, which led to independent rulers attaining greater regional power.

The election of Rudolf IV as the first Holy Roman Emperor from the Hapsburg dynasty brought the interregnum to an end in 1273. Before this, Rudolf spent much of his life violently and cleverly accumulating land for his family. The Hapsburgs held their possessions collectively, unlike other families that split their lands among their progeny, often resulting in the disappearance of both the family and its inheritance. Rudolf inherited seven lordships, and by the time of his death he had obtained nearly 50 lordships through various means, including conquest, marriage, purchase, and pressure. Upon hearing of Rudolf’s ascension to the throne, the Bishop of Basle famously said, “Hold onto your seat Lord, or else Rudolf will surely grab it.”

Upon the death of Emperor Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg on August 24, 1313, an armed power struggle occurred between Louis IV of the House of Wittelsbach of Bavaria and Frederick the Fair of the House of Hapsburg. Fearing the expanding power of the Hapsburgs, the three Forest Cantons threw in their lot with Louis IV. Only a spark was needed to ignite the smoldering conflict between the Forest Cantons and the Hapsburgs.

Such a spark was provided by the long-standing conflict between the Benedictine Abbey of Einsiedeln in northern Schwyz and the rest of the canton. In 1274, Rudolf I in his capacity as king of the Romans granted the abbey allodial status. Blurring the lines between the imperial authority and familial allegiances, the House of Hapsburg continued to exercise patronage and protection over the abbey.

The Einsiedeln Abbey owned the village of the same name and the lands in its immediate vicinity. Besides being a noted center of learning, the abbey became a burgeoning hub of large-scale cattle raising. The abbey’s steadily expanding grazing lands led to inevitable conflict with the small subsistence-level farmers and shepherds of Schwyz valleys, igniting a conflict over grazing rights that lasted almost two centuries.

Mutual complaints exploded into violence when on January 6, 1314, a large group of Schwyz men, who were led by their magistrate, Werner Stauffacher, attacked the Einsiedeln Abbey. The attack violated established norms. Stauffacher’s 300 men plundered the abbey’s food stores and residences and drank the monks’ wine. They also smashed altars and holy relics. After they had desecrated the church, they burned the abbey’s documents and took nine monks with them as prisoners.

It is possible that this incident took place with the tacit approval, if not active support, of the Imperial Reeve of the Forest Cantons Count Werner von Homberg. An experienced warrior who participated in the Livonian Crusades, Homberg inherited his mother’s lands around the town of Rapperswil in the northern part of Schwyz in 1289. It did not take long for Albert I of the House of Hapsburgs to lay claim to von Homberg’s lands, causing him to side with the residents of Schwyz. His exact role in the Einsiedeln affair is unclear, but he must have played some part since he was excommunicated by the Bishop of Constance along with Stauffacher. Upon Louis IV’s ascension to power in 1315, the excommunication was lifted.

While the stage was set for an armed confrontation, it took almost two years for Frederick the Fair, who also was known as Frederick the Handsome for his long, flowing, golden locks, to turn his attention to Schwyz. Compared to Frederick’s struggles with other powerful aristocratic families, the Forest Cantons were apparently low on his priority list.

Turning his attention to the Forest Cantons in late 1315, Frederick delegated his younger brother, Duke Leopold I of Austria and Styria, the task of teaching a lesson to the upstart peasants. An energetic and capable man, sometimes called Leopold the Glorious and nicknamed the Sword of the Hapsburgs, Duke Leopold arrived at the city of Baden in the northern canton of Aargau in October 1315. Born and raised in Austria, the 25-year-old duke was accompanied by a contingent of heavily armored Austrian knights and their retainers. It is likely that Leopold took only the mounted men-at-arms on his more than 400-mile journey from his family’s Austrian possessions to the city of Baden.

Duke Leopold called upon all of the towns under his authority to send the required number of troops for service. In addition, he instructed the nobles who were allies of the House of Austria to join his army. Their objective would be to attack the Forest Cantons and Schwyz in particular. The forces were to rendezvous on November 14 at Zug.</p

Leopold held the Swiss in contempt. He considered them to be not much better than an armed rabble. He proclaimed his intentions to crush the unruly rustics under his feet. Since he was an experienced and professional commander, he made some tactical dispositions.

The duke planned to lead the main attack against Zug himself. The duke tasked Count Otto von Strassberg, the Magistrate of Oberland in the canton of Bern, with conducting a diversionary raid through Bruning Pass against the canton of Unterwalden, and the militia of Lucerne with outfitting and launching a small armed flotilla to threaten Schwyz from the headwaters of Lake Lucerne. These ancillary movements were designed to isolate the Swiss from the two other cantons. For the time being, Leopold planned to leave Uri unmolested. He believed that the defeat of the men of Schwyz would bring about its ultimate submission.

Word of the upcoming invasion quickly reached the leaders of the Forest Cantons. While Leopold was gathering his forces in Baden, the Forest Cantons began preparations of their own. Their representatives unsuccessfully appealed to Count Strassberg and the city fathers of Lucerne to remain neutral. Their appeals did bear some fruit. Unterwalden was able to reach an agreement with the city of Interlaken in the canton of Bern, closing down the pass between Lakes Thun and Brienz, while the town of Arth broke away from the Hapsburgs and joined the Forest Cantons.

The canton of Uri, lying south of Schwyz and Unterwalden, was not directly exposed to Leopold’s attack, while the canton of Unterwalden’s primary threat came from the west, through the Bruning Pass. The canton of Schwyz, however, was greatly vulnerable to attacks from multiple directions, including amphibious landings from Lake Lucerne. Overland approaches to the heart of the canton, the city of Schwyz, were along Lake Zug through the town of Arth, along Lake Ageri through the town of Sattel, and from the direction of Einseideln through Rothenthurm to Sattel.

The real defensive strength of Schwyz rested not on the walls of its towns and cities, but in the difficult mountainous terrain. To further enhance the defensive advantages of narrow valleys and steep hillsides, the Swiss had a tradition of building earth and log fortifications, reinforced with stone guard towers, across the valley floors. These fortifications were called Letzi and some of them were quite substantial. The Letzi near the town of Arth was close to three miles long and 12 feet high with gates and three strong towers.

While the majority of able-bodied men of the Forest Cantons were mobilized, the bulk of the Unterwalden and Uri militias remained in their home districts. Numerous approaches by land and water had to be guarded and garrisoned. Moreover, a chain of outposts had to be established to keep in constant communication. The canton of Schwyz, being the most threatened, staged its field force of 1,300 men north of the town of Schwyz, reinforced by 300 men from Uri and 100 from Unterwalden.

Leopold’s scouts reported that the roads through Arth and Rothenthurm were blocked by Letzen and garrisoned by the Confederates; however, the road through Sattel at the foot of Morgarten Mountain was left open. It was guarded only by a watchtower in the hamlet of Schornen, north of Sattel. Unlike the defensive towers at Arth and Rothenthurm, the 40-foot-tall tower at Schornen was purely for observation, as it was not reinforced by a Letzi.

The hamlet of Schornen lies at the foot of a spur of the Morgarten Mountain, astride the road to Sattel. There the valley is approximately half a mile wide, with Morgarten Mountain on the east and Wildspitz Mountain on the west. The southern edge of Lake Ageri lies approximately half a mile to the north, where the Trombach Creek flows into the lake, creating a wide stretch of marshy terrain. Schornen lies immediately inside the border of the canton of Schwyz, while the hamlet of Morgarten lies immediately inside the canton of Zug, its houses scattered along the narrow road along Lake Ageri. Doubtless, any construction of a Letzi at Schornen would have been quickly spotted by men of Zug and reported to Duke Leopold.

It would seem that leaving the pass at Schornen undefended was an unlikely oversight, especially taking into the account that positions at Arth and Rothenthurm were strongly defended. Stauffacher had crafted a clever battle plan.

Even though Stauffacher left the trap door open at Morgarten, he still had to position his field force at a location equidistant to Letzen at Arth and Rothenthurm in case Duke Leopold did not fall for the ruse. Swiss success depended on the ability of its scouts to correctly observe and report the route of Austrian advance and the ability of the Swiss field force to reach the threatened location in time to set up an ambush.

In the early morning hours of November 15, 1315, the column under Duke Leopold left the city of Zug. Leopold had 2,000 cavalry and 6,000 foot soldiers. The core of Leopold’s mounted forces consisted of heavily armored Austrian knights. The Austrian knights were supplemented with knights from the noble Swabian families of northern Switzerland within the Hapsburg sphere of influence. Most of the knights wore full suits of plate armor and carried lances in keeping with the best traditions of medieval chivalry. The infantry, some of it possessing quality arms and armor, was levied locally from the cantons of Zurich, Luzern, and Zug. A knight on campaign was responsible for providing rations and supplies for himself and his retainers. For that reason, the invading force assembled a large wagon train full of supplies.

The road from Zug to Sattel taken by Duke Leopold ran along the east bank of Lake Ageri. The road was narrow and the cavalry could not advance more than three abreast. The infantry trudged behind the cavalry and the wagon train brought up the end of the column. Despite the chilly weather and icy road, the mood of the Austrian knights was light, resembling a hunting foray rather than a military campaign. Their helmets, hauberks, and weapons glinted in the sunlight. They were still in friendly territory and did not yet expect opposition. The road south was hemmed in between the steep bank of Lake Ageri and the rolling foothills of Morgarten Mountain. As the Hapsburg force passed through the hamlet of Haselmatt and continued south along the lake toward Morgarten, it would have noted that the hillsides were becoming much steeper.

The precise location where Stauffacher sprung his ambush is still a subject of debate. It is likely that the Swiss leader did not want his opponents to reach the open area south of Lake Ageri, which would allow the Austrian force to at least partially deploy before approaching the watchtower in Schornen, on the Schwyz side of the border with the canton of Zug. The distance between the town of Zug and Schornen is approximately 16 miles, taking roughly three hours to travel, and Stauffacher must have had sufficient advance warning to move his men into the ambush position on the slopes of Morgarten Mountain above the road to Schornen.

Approaching the hamlet of Morgarten, still in the canton of Zug, the Austrian column came upon a small barricade of logs and rocks barring the road. As a number of leading horsemen dismounted to pull aside the obstacle, 50 Schwyz crossbowmen rose up from behind the barricade and on the hillside above. Fired with devastating effect at close range, the bolts toppled men and horses in a tangled mess. Some Austrians attempted to clamber up the hillside to get around the barricade, but slowed by their armor and steep terrain, they were picked off the hillside by Schwyz crossbowmen.

While the fighting started at the head of the column, more Austrian men-at-arms began arriving and bunching up in front of the barricade. The previous day the Swiss had felled trees and positioned logs and rocks which were pushed downhill on the enemy.

The heavy material toppled horses and their riders, killing and maiming large numbers in the process. Others were crushed and pinned by the heavy materials or knocked into the lake below. The event caused great confusion up and down the entire Austrian column. Horses reared and kicked, injuring their riders, adding to the general confusion.

Several men of Uri blew large war horns called Harsthorner as encouragement to their fellow soldiers. The main body of Swiss mountaineers charged downhill from their hidden position on the ridgeline and fell upon the armor-clad men-at-arms that were bunched together in the narrow pass. Wielding their powerful halberds, the Swiss hacked at their foe.

Despite the frozen and slippery ground, the surefooted mountaineers appeared not to have difficulty navigating the treacherous terrain. Very few of the Swiss had any armor, only a scattering of steel caps and breastplates. Most wore only leather jerkins marked with the white cross of Schwyz or the black bull’s head of Uri. Their unheralded secret weapon was the crampon, consisting of metal spikes driven through a piece of hard leather and attached to the bottom of the mountaineers’ shoes. While the armored men and horses of Duke Leopold’s column had difficulty keeping their footing on the icy road, the men of the Forest Cantons plunged into them. They cleaved right and left with their halberds, long swords, and simple clubs cracking open skulls, dismembering limbs, and causing other grievous and fatal wounds.

The mounted knights in the front rank were bunched so tightly together following the attack by the Swiss that they could neither bring their lances to bear in a horizontal position nor spur their horses for a change. The Swiss slayed them in short order. Leopold’s army was bottled up in the narrow pass unable to advance or retreat.

At one point, the remaining mounted troops decided to turn back and ride through their infantry. In the confusion that followed, hundreds of foot soldiers were pushed over the lip of the road and fell into the deep water on the left. Most of those knocked by logs or by their fellow soldiers into the lake drowned. The small number of mounted troops who made their way to the back of the pass attempted to flee to safety, but the Swiss soon came pouring down from the hillsides to attack the rear of the column. Between the fear and confusion, the Austrians put up little resistance. The Swiss dealt out great slaughter without meeting much resistance at all.

“This was not a battle, but a mere butchery of Duke Leopold’s men; for the mountain folk slew them like sheep in the shambles: no one gave any quarter, but they cut down all, without distinction, till there were none left to kill,” wrote 14th-century chronicler Johannes of Winterthur, whose father survived the ambush and later described the slaughter to him. “So great was the fierceness of the Confederates that scores of the Austrian footmen, when they saw the bravest knights falling helplessly, threw themselves in panic into the lake, preferring to sink in its depth rather than to fall under the fearful weapons of their enemies.”

The “fearful weapons” of the Schwyz mentioned in the account were halberds, capable of puncturing and crushing the full plate armor that was common in the 14th century. Mounted on a long pole, the straight-edge axe head featured a spear point on top and a spike or a hook on the back to pull a mounted warrior off of his horse. At the time of Morgarten, halberds were the primary melee weapons of Swiss mountaineers, inexpensive to produce and employed with devastating effect by powerful men. Another fearful close-combat weapon used by the Swiss at Morgarten was the military flail, a staff weapon set with iron spikes. The flail combined the offensive effectiveness of the mace with the long reach of a spear.

Leopold attempted in vain to rally his men, but there was no saving the day as vicious the halberds of the Swiss continued to rise and fall. Count Wilhelm II von Montfort-Tettang, the commander of the Austrian vanguard, perished along with most of his men. The Austrian column dissolved into a disordered mob as the men fled, discarding their weapons and armor, trampling those who fell in the tight press of the rout. Cutting through the Austrian cavalry, men of the Forest Cantons fell upon Leopold’s Swiss levy infantry, quickly and bloodily routing them as well. In his flight, Duke Leopold had to fight his way through his own ranks to escape the trap. Leopold was seen riding away from the battle “half-dead from extreme sorrow,” wrote Winterthur.

The Confederates continued the pursuit for a short distance, methodically slaughtering Austrian wounded. The defeat suffered by the Austrians was devastating. Leopold lost 4,500 men at Morgarten, including the majority of his knights. In contrast, the Swiss suffered only light casualties. So many men were alleged to have perished in Lake Ageri that according to local legend, the water in the lake turns blood-red at midnight on the anniversary of the battle.

One of the hallmarks of the Swiss victory at Morgarten was the utter lack of mercy with which the Swiss butchered the Austrians, including the wounded. Single-minded disregard for their own and their foes’ lives made the Swiss dreaded opponents for the next 200 years. Despite the likely effect of inflating the number of Austrian dead and reducing the number of Swiss fallen, the disaster was devastatingly one sided. News of the defeat spread quickly. The flotilla from Lucerne returned to its city and Count Strassberg retreated through the Bruning Pass, hounded by men of Unterwalden who gave no quarter.

Shortly after the Battle of Morgarten, on December 9, 1315, representatives of the three Forest Cantons met again to reaffirm their mutual defense treaty and outline additional details of cooperation between the signatories. This was the beginning of the modern Swiss state. The resulting document, the Morgarten Letter, saw the first use of the word Eldgenosse, meaning Confederacy, in reference to the new Swiss polity.

The decisive defeat of the Hapsburgs at Morgarten gave significant impetus to the Swiss national movement. Lucerne joined the Everlasting League in 1332. Increased aggression against other cantons increased their desire to seek the safety in numbers that the league furnished to its members.

When Bern began expanding its boundaries in the late 1330s it earned the animosity of the rival town of Fribourg 18 miles to the southwest, as well as the excommunicated Emperor Louis the Bavarian and the bishops of Basel and Lausanne. The Kiburg family controlled Fribourg, and they were avid supporters of the Hapsburgs. In anticipation of an attack from the direction of Fribourg, the Bernese improved the fortifications of Laupen. The village had previously belonged to the Kiburgs until the Bernese annexed it.

The Fribourger army co-commanded by Rudolf von Nidau and Gerard de Valengi consisted of 3,000 cavalry and 12,000 infantry. In addition to local mounted knights, many Burgundian and Austrian knights had come to the support of the Fribourgers. They besieged the village of Laupen on June 10, 1339, and awaited the arrival of the enemy. It was a major operation given that the Fribourgers had an artillery train consisting of catapults transported by horse-drawn carts. The lords, knights, and men-at-arms of the Hapsburg-Burgundian force were resplendent in their armor and surcoats. “They gloried in their multitude and power and in the many decorations of their new and costly vestments,” according to the Conflictus Laupensis,a 14th-century chronicle.

When they learned that Laupen was under siege, the town leaders of Bern held a council of war. They resolved to march immediately to the aid of the beleaguered 600-man garrison for fear it might be slaughtered if the village was captured. Bernese knight Rudolf of Erlach led a Crusader-like army of zealous foot soldiers who marched under banners bearing a dark cross on a white background. Moreover, each man had sewn a white cross on his clothing.

The full levy of Bernese turned out. On June 20 it rendezvoused with the Confederates of the Forest Cantons at Bumplitz three miles west of the city. The Swiss found the enemy encamped in a strong position on a wooded hilltop known as the Bramberg. Erlach and his captains ordered their troops to form into two columns. The right column consisted of Bernese troops and the left column of men from the Forest Cantons.

The right column, which deployed at the top of a steep slope, faced the Fribourg foot, and the left column, which was arrayed on a gentler slope, faced the imposing Hapsburg and Burgundian knights. Erlach, a veteran of many local wars, planned to charge down on the Fribourg foot.

The Fribourgers attacked on the afternoon of June 21. The Fribourg infantry advanced on the Bernese in two divisions. Bernese slingers showered the enemy with stones as they advanced. The Fribourg foot proved no match for the Swiss. The Swiss of the right column formed into a wedge, charged downhill into the enemy, and drove deep into their formation. They slashed their way with determination toward the enemy banners. The Fribourg foot lost their sense of cohesion and fled the field.

The Bernese of the right column, although exhausted from the fighting, nonetheless went to the aid of the hard-pressed left column. The combined weight of the two divisions of Confederated Swiss foot drove off the Hapsburg and Burgundian cavalry.

When it was over, the Fribourgers had suffered 4,000 casualties to the Bernese 1,500 casualties. The victorious Bernese triumphantly took home 27 captured banners.

Bern, Glarus, Zug, and Zurich joined the four original cantons in 1353 to create the Confederation of the Eight Cantons. Like Bern, Lucerne also embarked on an aggressive policy of expansion, entering into alliances with the towns of Entlebuch, Sempach, Meienberg, Reichensee, and Willisau. Not surprisingly, the Austrian dukes saw this as an infringement on their territorial interests. By the end of 1385, the Swiss Confederation engaged in active harassment of the Hapsburg city of Rapperswil and other localities that were sympathetic or allied to Austria.

Unable to resolve the matter through diplomacy, Austrian Duke Leopold III assembled an army drawn from his vassals in Swabia, Tyrol, and Alsace. To round out the army, he instructed various Austrian towns to furnish additional troops. The 4,000-strong Austrian army assembled at Brugg in late June. The majority of the force was mounted.

The presence of the Hapsburg forces at Brugg seemed to indicate to the Confederacy that Zurich was its intended objective, given that it was the closest major town. The Swiss Confederacy assembled a force consisting of troops from Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden. Initially they prepared to take up a position to defend Lucerne, but when they realized that Leopold’s army was marching south toward Lucerne rather than east toward Zurich, they countermarched. The 3,000 Swiss foot were led by Petermann von Gundoldingen, a wealthy resident of Lucerne.

On July 9, 1386, the two sides meet near the town of Sempach, which was situated nine miles northwest of Lucerne. The Austrian knights leveled their lances and charged downhill into the force of Swiss pikemen and halberdiers, inflicting heavy losses. But the Swiss were far from beaten. During the course of the ensuing bloody melee, the Swiss gained the upper hand and Leopold was slain. The Austrians suffered 1,000 casualties compared to 200 Swiss casualties.

The Battle of Sempach was the event that transformed the Swiss Confederacy into a serious military power. It would be more than a century before the last battle between the Swiss and the House of Hapsburg was fought during the Swabian War of 1499.

The Swiss struggle for an independent national identity was the clarion call for the eventual disintegration of the Holy Roman Empire. The glue holding the empire together was the Catholic Church, with the crowning by the pope giving legitimacy to the Holy Roman Emperor. The armed struggles between Protestant and Catholic states in Europe, especially in Germany, culminating with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, ended the supremacy of the Holy Roman Empire. Under the terms of the treaty, Switzerland gained its independence, outliving both the Holy Roman Empire and its successor Hapsburg monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments