By Kelly Bell

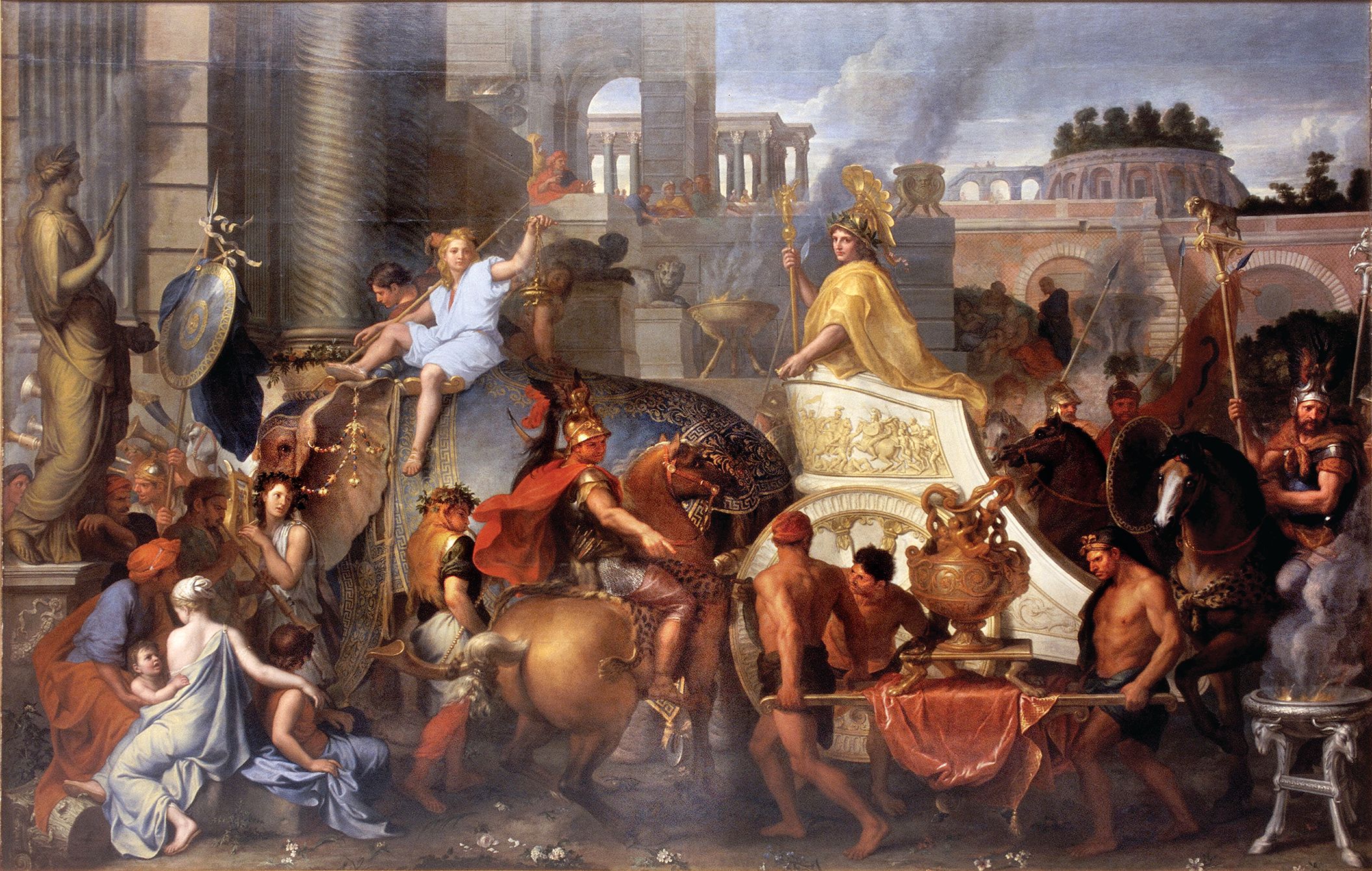

He was the first Caucasian many of his conquered subjects had ever seen. The empire he established during his short life stretched from Greece to the Indus River in modern Pakistan, an area of about 2 million square miles—more than twice the size of the Louisiana Purchase. His was a time in which war, bloody campaigns and conquest were not viewed so much as brutal aggression, but (in this case) as a route to winning the moniker “the Great.” Despite his bloody hands and steadfast, altruism-bereft resolution this charismatic young warlord would probably be called Alexander the Great even had he lived and fought today.

His empire encompassed all or most of what are now called Turkey, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Libya, Cyprus, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, central Asia, Pakistan and as far as India. He was just 20 when he set out after what some would call immortality. His father King Phillip of Macedon had just been assassinated. Sobered by this personal tragedy and fearful of its implications for his own future, Alexander, in 336 B.C., headed for Delphi to consult its oracle.

Although believing in its visions he was unimpressed by the reputation and reverence attached to this congregation of priests and the seeress they served. Alexander stormed through the coterie of aghast holy men, strode into the prophetess’ chambers unwashed, without respectful attire or invitation and demanded a precognitive report on his planned campaigns. When the imperious old lady refused, he seized her gray hair, dragged her into the temple and repeated his order. The historian Plutarch later recounted what followed.

“As if conquered by his violence she said, ‘My son, thou art invincible.’”

“That is all the answer I desire,” replied the ambitious, fearless youth.

Alexander was a small man with flowing blond locks and a beardless countenance whose big, round blue eyes made him look too innocent to be a dashing, formidable figure. He never let his appearance impede his career and his thirst for glory as he carved out a sprawling realm via untouched courage, leadership, battlefield brilliance and a willingness to be ruthless on occasion.

The 13 years he spent with his armies transformed his part of the world. He overhauled civilization throughout his massive, conquered realm that stretched from Europe to Asia. It did not long outlive him, breaking up soon after his passing, but its very existence and how he brought it into being won him such acclaim as to establish him as a martial/cultural institution. Although succeeded by such paladins as Caesar, Charlemagne, Khan, Napoleon, Shaka and Hitler it is Alexander who holds the status as the first of the great conquerors, and he is the only one of them called “the Great.” These others merely followed in his legendary footsteps. He showed them the way.

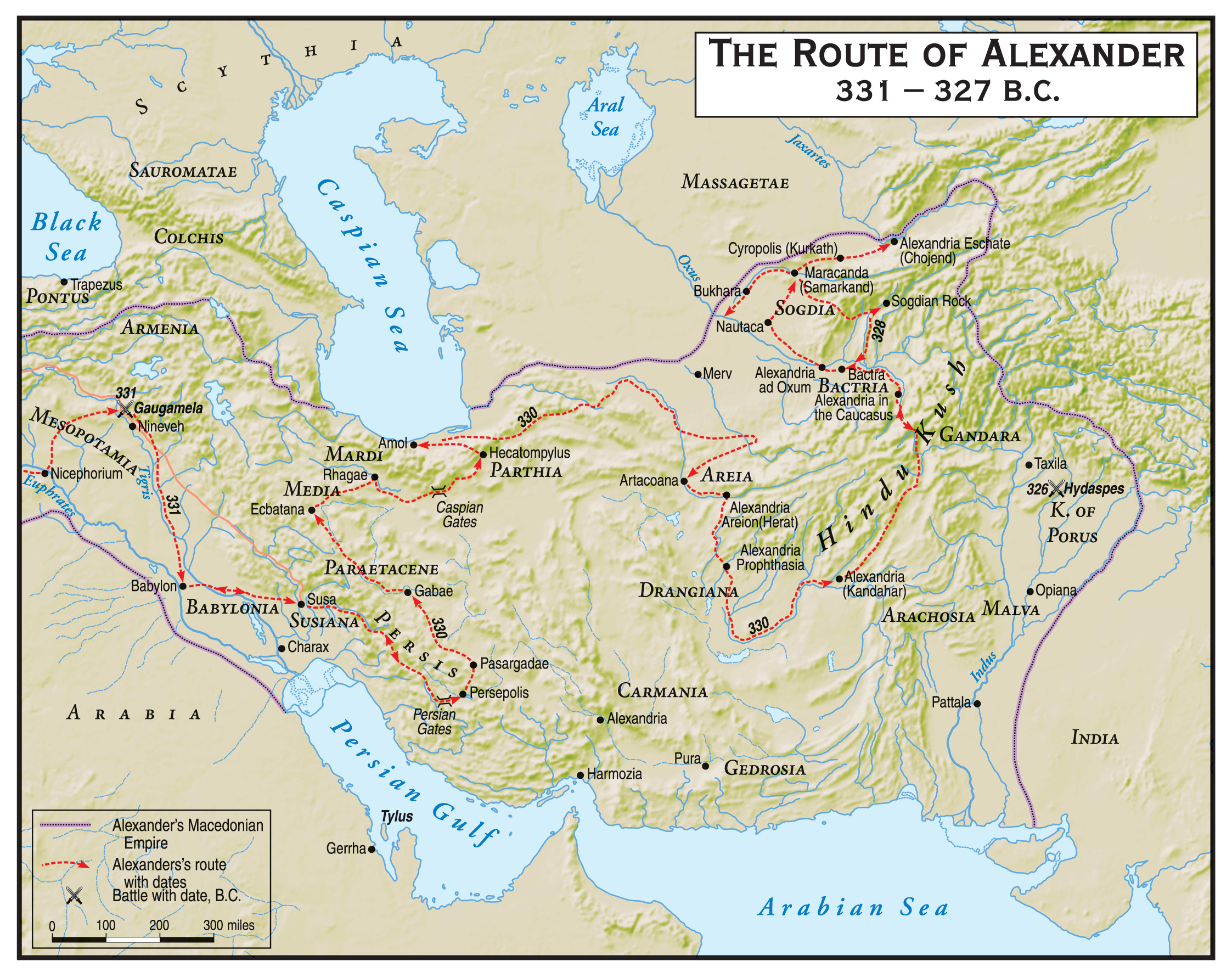

Seemingly incapable of being intimidated, Alexander, in 334 B.C. turned his eyes eastward toward the gargantuan Persian empire that stretched north into what later became Russia, south into Egypt and east into India. He was king of Macedonia and undisputed ruler of all Greece. Now that he was in a position to do so, he could hardly wait to war on the Persians.

In 480 B.C. Emperor Xerxes had overrun Greece and Persia, and burned Athens. Greece withstood the assault under the leadership of King Leonidas, and aided by a hurricane that destroyed the Persian fleet. Inspired by the heroism of their king and his small personal bodyguard at Thermopylae the Greeks drove Persian King Xerxes back across the Dardanelles. More than a century later Macedonian leaders still thirsted for and preached vengeance, and Phillip may have been planning a retaliatory, eastern campaign when he was assassinated. He had conditioned his son for war, and Alexander almost certainly suspected the Persians of complicity in his father’s death.

Having conscientiously studied logic under the great philosopher Aristotle, and further schooled by his passionate and violent mother, Olympias, to fight and live with abandon and recklessness Alexander was conditioned for a life on the battlefield, campaigning offensively and irresistibly.

Starting out with an army of 35,000 he swept through Asia Minor, and then turned toward the eastern Mediterranean, taking its maritime provinces and thus rendering the dread Persian fleet irrelevant. He proceeded to take on the Persian King Darius III, overwhelming him and usurping his lands and titles. But it was not nearly enough.

Although now rich in acclaim and booty, Alexander spent his seven remaining years conquering lands stretching from the Russian steppes to India’s Indus Valley—no human foe could stop him. At the end of his crusades he succumbed to ill health and widespread disillusionment among his homesick, dwindling troops. Realizing they had a valid complaint, he returned with them to conquered Babylon, where he died childless at 32, and his huge but poorly administered empire fell apart under the inept governing of the generals to whom he bequeathed it.

Still, his influence had stitched together many kingdoms, countries and satraps into mutually supportive trade partners. He had explored and mapped previously unknown territories, founded conurbations and stimulated the profitable exchange of ideas, customs and commodities between East and West. Greek became the tongue of the educated elite from the Mediterranean to India, creating crucial communication that made vital interaction possible and effective. It was his brilliance that conceived the notion that victors and vanquished could live together in opulent harmony.

He spent his formative years in the Macedonian city of Pella (now Nea Pella,) where archaeologists still exhume columned temples, mosaic-adorned stone floors and beautiful artwork and sculptures. Millenia later the local Supervisor of Antiquities, Photios Petsas, said the historically rich site is still revealing its secrets.

“These may be the palaces of Alexander’s generals, built soon after his death,” Petsas said. “We expect to find Phillip’s palace on the west side of the present village.”

It was here Alexander, 13, broke and rode the only horse that would ever carry him. He would name the fiery stallion “Bucephalus.” A trader had tried to sell the steed to Phillip, but the king and trainer after trainer failed to break the animal as he sent men flying from his back. Phillip despaired of ever taming the massive mount-to-be, but the crown prince had hope.

“I can manage this horse,” said the boy.

He turned the hulking creature to face the sun so that he no longer could see his own threatening shadow. Bucephalus instantly became quiet and docile and Alexander rode away on him. His face a river of tears, Phillip cried out:

“O my son, look thee out a kingdom worthy of thyself, for Macedonia is too little!”

Phillip relentlessly worked his boy to prepare him to achieve this adjuration. The adolescent Alexander learned to kill lions with spears, both fight and command in the field, and to concoct brilliant battlefield strategy. The young man eagerly threw himself into these preparations, excelling in every field and thirsting for the day he would be at the head of rampaging armies. His eagerness led him to fret over Phillip’s successes, lamenting, “Will my father leave me nothing to do?” Alexander would find plenty.

In 336 B.C. Phillip of Macedon died at the hands of a band of dagger-wielding assassins. Alexander unhesitatingly ascended to the throne and crushed a series of anti-Greek revolts with sobering totality. After pacifying rebellions from the Danube to Thebes, he deployed the 35,000-man force of infantry and cavalry in the spring of 334 B.C. This army was followed by supply trains, botanists, geographers and sundry scientists to insure Alexander would not only conquer, but learn all there was about the lands he was subjugating. Aristotle had impressed on him how the need to know is as vital as the need to rule. Upon fording the Axios River he plunged into his new world of conquest, never to return home.

After 20 days and 300 miles he and his army reached the town of Sestos on the western shore of the Strait of Gallipoli (also known as the Hellespont.) To the east lay the rich and powerful Persian Empire. This realm used its wealth to hire and meticulously train a massive, formidable fighting force, many of them Greek mercenaries. Spies had been closely monitoring Alexander’s progress, and as his men boarded galleys to ferry them eastward the forewarned Persians were hurrying to a point on the Granicus River two miles’ march inland, where they deployed to meet the incursion. But before marching to battle, Alexander temporarily left his troops with his second-in-command General Parmenion, and boarded a galley southward to Troy.

Alexander had brought along his prized possession, a copy of Homer’s Iliad given to him by Aristotle. He slept every night with the tome under his pillow, reading its passages until they were frayed and dog-eared. Obsessed with the Trojan War of almost a millennium earlier, he idolized Achilles and described the Iliad as the “perfect portable treasure of all military virtue and knowledge.”

His foray to Troy was his means of obtaining an icon from the flesh-and-blood demigod he adored. After arriving in the city he made for the Temple of Athena and purchased a shield he believed had been carried by Achilles himself. His faith would be vindicated. This shield would later save his life. Re-boarding his ship he headed north to face Persia. The campaign would last 10 years.

Alexander returned to find both his army and their foes deployed along the deep, swift Granicus. The veteran Parmenion, who was old enough to be his commander’s grandfather, futilly urged caution when it came to fording this surging stream.

“I should disgrace the Hellespont should I fear the Granicus,” replied Alexander, spurring his horse into the river.

Many of his men later recounted how he made something of a comical sight. Diminutive as he was, he seemed even smaller astride his huge mount. It looked almost as if Bucephalus was carrying a child, but this little warrior fearlessly plowed through the torrent amid a downpour of arrows and spears. His troops were too proud to not follow his example, and unhesitatingly plunged into and through the torrent. Shocked by the ferocity of the Macedonians’ assault the entire Persian force quickly broke and retreated in disorder.

Realizing his authority was only as strong as his army’s support, he had his dead buried with full military honors, and exempted their families from taxation and conscription. Circulating among his wounded, he questioned each of them as to their proclivities during the battle, encouraging them to take credit for the acts of individual heroism that had brought on such a smashing victory. Such astute handling of his soldiers brought him their enduring loyalty.

The rout on the banks of the Granicus gave him a firm foothold in Asia, but was just the beginning. Darius’ main army was a full 1,000 miles to the east, so it posed no immediate peril, but the Persian fleet seriously outnumbered Greece’s and controlled the seas. Alexander decided the best way to neutralize his enemy’s naval superiority was to destroy its maritime provinces. He turned south and headed for the Turkish seacoast.

He would have widespread local support from these coastal enclaves peopled by descendants of Greek settlers who had little use for the Persians who had conquered their region. In Ephesus the residents rose in revolt upon Alexander’s approach, stoning Persian officials and greeting the Macedonians as liberators. One after another, the populations of Turkey’s coastal cities joyfully threw open their gates to this army they regarded as their own. In each town he confiscated no more than absolutely necessary to support his command. When a Greek-descended mayor asked him why he did not plunder more from such an opulent empire he replied:

“I hate the gardener who cuts to the roots the vegetables of which he ought to cull only the leaves.”

With little bloodshed he pressed on to Miletus and Halicarnassus, where powerful Persian garrisons awaited. It took another seven months to overpower these troop concentrations and pacify the coast.

After resting his army until spring he led it across the lofty Anatolian Plateau to Gordium where, according to legend, he solved the challenge of the renowned Gordian knot by simply slicing it apart with his razor-sharp sword. It was believed that whoever untangled this ropey mass was destined to rule Asia.

Making plans as he moved, he marched resolutely toward the main Persian army, overrunning Cappadocia en route to the sole gap in the otherwise impassable Taurus Mountains. It was called the Cilician Gates, and was so slender his cavalry had to pass through it in single file. Similar to the bottleneck at Thermopylae, the pass might have stopped his progress, but Alexander rushed through it in a night advance that surprised its sleeping defenders and sent them scurrying. Bearing southeast he made for Darius.

They met in the autumn of 333 B.C. at Issus, and the again-outnumbered Greeks outmaneuvered and outfought the swarming Persians. Alexander called his elite cavalry his Companions, and in this brouhaha he led them in a wild charge into their opponents’ horsemen that broke their ranks and cleared the way for the Macedonian infantry to charge with their thousands of spears leveled. Seated atop massive Bucephalus, Alexander had a panoramic view of the battlefield, and spotted the Persian king’s portable pavilion. Screaming for his cavalry to follow he led a charge on the royal retinue. Darius prudently abandoned his bivouac, mounted his own horse and fled, managing to maintain a safe distance between himself and the pursuing Greeks until dusk. He escaped under cover of darkness.

Although frustrated at his foe’s evasion, Alexander returned to Darius’ enormous tent and eagerly partook of the sumptuous fare the Persians had left.

“This, it seems, is royalty,” he remarked to his officers.

Still, apart from food, all he took for himself was a bejeweled coffin he thereafter used to hold his treasured copy of the Iliad.

After resting his army, cremating his dead and sending the severely wounded home in a wagon train, Alexander bore southward along the eastern Mediterranean coast. His next mark was the Lebanese port of Tyre, which was both a commercial/naval base and trade center for the whole Middle East. The Tyrians might have profited immensely by welcoming the Greeks as new business partners, but this too-proud island hub of lucrative commerce, surrounded by high walls, slammed their gates and refused him entry. He came up with an ingenious solution.

Showing himself to be a master of military engineering as well as tactics, Alexander devised an inexorable stratagem the city’s residents and defenders could readily see and diagnose, but were powerless to stop—he built a 200-foot-wide causeway to the island.

It took seven months under a constant cascade of arrows and catapulted rocks, the smallest of which were cabbage-sized. Finally his own trebuchets came within range of Tyre’s east wall and commenced cracking its facade while the southern wall crumbled under the assault of battering rams the Greeks ferried to the isle aboard captured boats. The offshore burg quickly fell, leaving the Persian fleet with no ports, and essentially putting it at Alexander’s command. The causeway is there to this day, widened by drifting sand.

The Tyrian siege had kept Alexander too busy to respond to a feeler from Darius. Now he turned his attention to this unexpected offer.

The emperor proposed a conditional surrender, offering to Alexander his daughter, 10,000 talents of gold, and all Persian-held territory west of the Euphrates—literally one-third of his empire. Although Alexander was already certain of his response to this proposition, he decided to call his senior officers together for consultation.

“Were I Alexander,” said the homesick old Parmenion. “I would accept.”

“So would I, were I Parmenion,” Alexander replied.

The young warlord had his eye on the whole of the Persian Empire, but first he had to get past Egypt. When he reached the pyramids he found the Egyptians had heard of his brilliant, devastating exploits and had no desire to oppose him. With much ado they crowned him Pharoah without spilling a drop of blood. He founded a city and gave it his name—Alexandria.

From then until now, Alexandria has been a hub of middle eastern culture even while governed by successive dynasties of Greeks, Romans, Crusaders and Muslims. Until the 1950s it was Egypt’s version of Las Vegas, and although Cairo is now the country’s heart and soul, Alexandria remains a favorite resort city for Egyptians. It all started with Alexander.

“Now Cairo is the hub of Egypt,” opined an Alexandria businessman 2,400 years later. “Alexandria is like an empty stage. All the actors are gone…the aristocracy, the landowners, the foreign elements, everyone who gave the city life.”

All the while he was laying out the confines that would be Alexandria, Alexander felt a compelling urge to consult another source of precognition. Specifically, he desired to visit the renowned oracle at Siwa Oasis. It took him a month to reach the verdant patch of date palms, ponds and green fields encircled by featureless, dry desert.

Today the Oasis remains a beehive of activity as packaging plants, olive oil pressing facilities, clinics and schools where young Egyptian women are being educated in the nation’s first co-ed learning center.

Alexander arrived on his faithful Bucephalus, to be met warmly at Siwa by the chief priest of the sect of Ammon, the Egyptian equivalent of Zeus. The conqueror and the holy man went alone into the Oracle. The time was drawing near when the campaigning Macedonians would have to meet Darius and his main army, whom Alexander took very seriously. He never disclosed the prophecy the Oracle gave him, but he emerged from its confines in high spirits and eager to continue his exploits.

After returning to Tyre, he allowed his troops to rest awhile longer, and then set out to the northeast, where his scouts had informed him Darius’ army waited and continued receiving reinforcements. Moving steadily across the rolling Syrian cropland, the invaders found it burned to ashes as Darius had employed scorched earth tactics to make it difficult for the Greeks to live off the land. Although refusing to stop, Alexander did slow his advance sufficiently for the crucial supply trains to keep up with the army. With time being of the essence, the Macedonians did not, as the Persians expected, stop to rest and refresh when they reached the Tigris River. Commandeering every available riverine conveyance, they crossed the river and headed straight for Darius.

Following Alexander’s rejection of his peace terms, the Persian emperor had resignedly but resolutely commenced preparations for the coming clash, putting his enormous army to work leveling the sprawling prairie outside the city of Gaugamela to the east of Mosul. His plan was to transform the countryside into a site ideal for his ranks of scythed chariots, which he aimed to send directly into the Greek legions, cutting bloody swaths through their ranks. Alexander anticipated him and devised appropriate tactics, but would still need a psychological haymaker to carry the day.

After carefully briefing his soldiers on the Persians’ likely strategy, he lined them up on the battlefield and sent them marching forward. Sure enough, hundreds of chariots came pounding at them at breakneck speed, the sharp curved blades protruding from their hubs flashing in the bright sunlight. Acting on their leaders’ orders the spear-wielding Macedonian infantry waited until the last possible instant before parting like the Red Sea. The charioteers were going too fast to stop or turn aside as they hurtled into the midst of the foot soldiers, who closed in and surrounded them.

After skewering the horses, the Greeks drew their swords, dragged drivers and archers from the chariots and slaughtered them. Alexander then spurred Bucephalus into the fray, and, followed by his Companions, made straight for the emperor’s pavilion. Seeing this onrushing threat, Darius leaped onto a horse and escaped.

Despite their initial success, the battle soon began going badly for the outnumbered Greeks as units were repeatedly outflanked and overrun by their teeming adversaries, but word began to spread among the Persians of their emperor’s departure. Disheartened at being abandoned by their leader, tens of thousands of his troops threw down their weapons and fled.

The battle was won, but Darius and most of his army had escaped. Still a threat, the Persian emperor and his legions would have to be followed and destroyed, but for the moment, the Macedonians needed time to recover. Trudging to Babylon, whose residents eagerly threw open their gates and welcomed them, the Greeks rested for a month, puzzled by the strange black liquid bubbling from the ground. They may have been the first westerners to see crude oil.

After settling in, Alexander appointed a Persian to govern Babylonia as part of his objective of uniting his own people with their conquered subjects, thus creating a stable realm. He and his men doubtless spent the next few weeks gaping at the Hanging Gardens, the Ishtar Gate and drinking in all of Babylon’s sumptuous fleshpots. Although they must have hated the thought of leaving this lush ancient city, they could not stop thinking about the untold riches beckoning from central Persia. After the month’s respite they resolutely set out eastward.

This desert trek was more challenging than combat as the Macedonians plodded through a heat-blasted landscape quivering with mirages that looked like lakes. The invaders needed camels to replace the sweat-drenched horses that were dying in droves, but since they could rarely catch these ships of the desert, the Companions found themselves unwillingly assuming the role of infantry.

Alexander’s first objective in this latest foray was Persepolis, and as he and his command emerged from the sea of sand and began to encounter villages and towns along the approaches. Eagerly plundering gold and silver coins and vessels, jewels and sundry lucrative furnishings they became rich from this area that so many centuries later would be opulent for oil production. Persepolis would be an even richer haul.

Darius had used his vast wealth to transform Persepolis into an opulent commercial and cultural center. Cedar imported from Lebanon was expertly carved and inlaid with silver and gold before being used to construct massive temples and public buildings supported by huge fluted columns topped by statues of charging bulls and soaring griffins. Beautiful woven tapestries covered the interior walls. The invaders gaped at the endless treasuries, palaces and packed storehouses, and confiscated herds of thoroughbreds from stables before drinking themselves silly and burning the magnificent palace of Xerxes in retaliation for the dead emperor’s razing of Athens 150 years earlier. Even after becoming perhaps the wealthiest army in the world by taking and plundering this extravagant metropolis, the Macedonians still had plenty of campaigning to do. After collecting and distributing their booty they headed north toward Hamadan in the spring of 330 B.C. Trailed by a lengthy wagon train heavy with plunder, they aimed to capture Darius himself and ransom him for a fortune.

Averaging an impressive 36 miles a day they quickly reached the city, but did not find the emperor. He had fled to the east through a gap in the Elburz Mountains called the Caspian Pass. Immediately resuming the chase the gracile expeditionary force soon overtook the plodding Persian wagon train only to find that, despite their rapid clip, they were too late to capture Darius—the Persian generals, having lost confidence in their feckless leader, had assassinated him.

They had mistakenly assumed Alexander would be pleased with them for ridding him of an enemy, but he viewed it as their having robbed him of a king’s ransom. After having them beheaded he marched his command to Zadracarta (now Gorgan,) where he was crowned Persia’s emperor in a setting of untouched opulence.

But he couldn’t stay long. Alexander’s spies informed him that Bessus, the Persian general who had planned Darius’ death, had fled to Balkh in what today is northern Afghanistan, set up a court, proclaimed himself king of Persia and was raising a new army. The Greeks headed east to meet this threat, but were diverted.

Just before reaching the Afghan border, Alexander learned a revolt had broken out in a province to the south. Leaving off his advance on Bessus he moved on this latest objective, launching an attack of extreme resolution and abandon and quickly crushing the rebellion. He left a garrison that remained there so long it evolved into the modern-day city of Herat. More uprisings were erupting yet farther south, so the Macedonians maintained that heading. Alexander soon faced a much closer threat.

They made it as far as Qala-i-Kang, where a mutiny in his ranks forced him to stop. Many of his men were becoming disillusioned with their leader because of his increasing affinity for all things Persian. He had appointed many Persians to high positions in his recently conquered holdings, and, determined to insure their loyalty to their new rulers, had appointed Persians to many high positions in the occupied territories. He even adopted Persian attire. Most of his troops, however, regarded these subjected people as little more than slaves. The mutinous elements were soon overwhelmed, but Alexander’s internal problems were just beginning.

Rumors began to circulate of a plot to assassinate him, and were sufficiently numerous for him to take them seriously. One of his ablest generals was Philotas, who possessed a brilliant military mind, but whose taskmaster ways made him quite unpopular within the Macedonian ranks. With little more evidence than the rumors themselves, Alexander had him court-martialed for treason, convicted and executed. Greek tradition decreed that the immediate families of traitors also be killed. Alexander spared all of Philotas’ relatives except his father, Parmenion. Possibly weary of the old man’s constant adjurations to leave off campaigning and return home and make a dire impression on any other potential mutineers, Alexander had him beheaded before invading southern Afghanistan, ranging through the region during the summer and autumn of 330 B.C.

Today this region is called Dasht-i-Margo, “Desert of Death,” but 23 centuries ago it was a well-watered savannah with numerous settlements. Modern-day provincial Vice-Governor Rsul Pashtoon notes that, “This wasn’t always a desert. When Alexander came through it was probably one of the more fertile regions of Afghanistan. There were canals everywhere. Then came Genghis Khan 15 centuries later. His Mongols ravaged the area, filled in the canals, massacred the population, and the sand took over. You’ll see dozens of ruined cities along the way.”

In December the army passed through the Kabul Valley, only to grind up against towering, snow-cloaked mountains. Bessus and his teeming entourage had made it past the peaks by using the sole aperture, the Khawak Pass, just before winter blizzards sealed the passage. Although it does provide a path through the towering peaks, it sits at 11,650 feet itself, and Alexander found it buried in hard-packed snow. Having stocked up with copious supplies in Zadracarta, he decided he could afford to wait out the cold months and resume chasing Bessus come spring.

As soon as the seasons turned he acted on what his calendar told him rather than what his eyes did, and set out through the pass before the snowpack melted. Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus later wrote of the Greeks’ plight as they advanced:

“The army, in this absence of all human civilization, endured all the evils that could be suffered—want, cold, fatigue, despair. The unusual cold of the snow caused the deaths of many. It was especially harmful to those who were fatigued. When they struggled to rise they could not do so, but were roused from their torpor by their fellow soldiers, for there was no other cure than to go on.”

Bessus had set up a base of operations in the city of Balkh. After the Macedonians finally cleared the mountain gap and headed for him, he gathered his troops and fled. After reaching the semi-deserted city Alexander realized his own troops were nearing the limit of their endurance. He secured Balkh and spent the next two years using it as a headquarters as he rested, reprovisioned, recruited and reconnoitered. While simultaneously sending out long-range mounted units to search for Bessus, he fought the regional nomadic tribesmen who ranged the area on both sides of the Oxus River. Although he eventually managed to subdue them, these hard-riding and hard-fighting horse soldiers so impressed him that he absorbed many into his own ranks. After seeing the stocks of glittering booty the Greeks had accumulated, these locals were eager to enlist.

After the two-year hiatus Alexander and his reinforced, rested army spent five days crossing the Oxus on rafts. No sooner had they commenced marching eastward than they encountered a Persian delegation that simply handed Bessus over to them in hopes of lenient treatment from this force they had come to dread. Having the usurper summarily tortured to death, however, did not end the warring.

New Persian leaders arose, and it took some hard campaigning by the Greeks to conquer the region called Samarkand, overrunning five cities in two days as this refreshed army gained momentum. When it reached a lofty, heavily fortified kingdom called Sogdian Rock and Alexander demanded its surrender, the confident defenders laughed and called down at their besiegers: “Find soldiers with wings. No one else can touch us.”

Under cover of darkness, 300 Macedonians used pitons and ropes to scale the promontory and breach the defenses of the fortress. At daybreak Alexander called: “Come see my flying soldiers.”

The Sogdians prudently capitulated, and their new masters treated them with civility. After marrying a local nobleman’s daughter named Roxana, Alexander embarked on a two-year offensive against the steppe nomads in what later became Iran and Afghanistan. After subduing the worrisome plains tribes and eliminating them as a threat to his rear, the young warlord again set his eyes eastward, toward India.

By the time he resumed campaigning in the summer of 327 B.C. the people of Sogdiana Rock had become very attached to their occupiers, who had greatly increased the kingdom’s material wealth. A great many accompanied the free-spending Greeks as they headed into what later became Bangladesh. In fact, it could no longer be accurately called a wholly Macedonian expedition as the influx of Persian mercenaries and sundry camp followers had swollen the coterie to 120,000 as it left Afghanistan through the Nawa Pass. The composition of the army was not the only thing that was different.

Alexander himself was a changed man. Seemingly affected by the strain of campaigning he was drinking heavily. Pitiless in his dealings with anyone who disagreed with him he was subject to violent temper fits, at one point hacking to death his old friend Black Cleitus, who had saved his life at the Granicus. Still, his multitude of troops were getting richer and richer off his conquests and remained devoted to him.

Soon after entering what is now northern Pakistan, the army encountered and were fascinated by an enclave of people who said they were descended from Dionysus, the Greek god of wine. Their form of government was similar to that of Greece, and Alexander’s Persian mercenaries told him their rulers had been known to exile Greek settlers from Asia Minor to their realm’s easternmost regions. He spared this tribe, but used its land as a base of operations as he spent the next several months fighting and eventually overcoming this region’s fiercely independent residents. It was an area barely the size of Connecticut, and the difficulty of this campaign brought on the first hints of discontent among the Macedonians.

Still, the soldiers were for the most part unified behind their charismatic and brilliant, if increasingly erratic, leader. In the spring of 326 B.C. his engineers constructed a bridge over the Indus River and Alexander entered India. His first encounter was with the king of Taxila, who had heard reports of the interlopers’ wealth and was anxious to do business. Alexander paused for a massive reprovisioning and refit before facing his first hostile Indian—King Porus.

Wide, deep and swift, the Jhelum River lay between the Greeks and Porus, with his bristling 35,000-man army and their 200 trained war elephants. While Keeping his foes off-balance via a series of feints, Alexander quietly had his men collect every floatable craft throughout the region. On a stormy night the Macedonians boarded their boats and crossed the river unnoticed. At first light they charged with such abandon they knocked Porus’ army off-balance and stampeded its elephants. Decimated and demoralized, the Indian army fled in disorder and never reformed. An unbowed Porus was captured. When asked how he wished to be treated the answer was, “Like a king.” Impressed, Alexander installed him as puppet ruler and expanded his territory. For many of the invaders, however, this latest bloodbath was the last straw.

They were receiving reports of additional and formidable armies awaiting them, and their accumulated riches were doing nothing to alleviate their homesickness, fatigue and heartbreak at seeing so many of their friends, brothers, cousins, uncles and fathers fall in battle. Their morale gone, Alexander’s troops refused to go on. He called a conclave of his senior officers to seek their advice, and his loyal and fearless General Coenus, who had served him faithfully from the beginning, rose to his feet, removed his helmet to emphasize that his fighting days were behind him and addressed his leader:

“Oh king, I speak not for those officers present, but for the men. Those that survive yearn to return to their families, to enjoy while they yet live the riches you have won for them. Lead us back now. A noble thing, Oh king, is to know when to stop.”

Alexander silently rose and stalked out of the meeting, and spent the next three days pouting in his tent. Still, he could see the writing on the wall and knew he was beaten. To resist this opponent would lead to self-destruction. Knowing he was beaten, he submitted to the will of his men. “Alexander has allowed us, but no other, to defeat him,” his jubilant troops proclaimed.

In the autumn of 326 B.C. part of the massive congregation headed downriver along both banks of the Jhelum while additional elements set out downriver aboard 2,000 vessels. It was a nine-month journey along the Jhelum, Chenab and Indus rivers, and the fighting was not over.

Several times the Greeks had to fight their way through cities whose residents did not trust them sufficiently to grant them peaceful passage. In one brouhaha, Alexander, furious at the lackadaisical performance of his soldiers during the siege of the city of Mallians, grabbed a ladder and climbed an inner wall of the citadel, followed only by two bodyguards. The stunned soldiers all tried to follow their leader at once and the ladder broke under their weight. His army quickly breached the ramparts and swarmed into and through the city, to find their leader prostrate in the town square with an arrow embedded in his chest.

Carefully carrying him semiconscious back to their bivouac, his troops believed the still form might be dead. Alexander ordered the arrow removed, but his men were afraid to try to cut it out. One of his generals, Perdiccas, is said to have finally removed the arrow. Alexander’s life hung in the balance for days and rumors of his death spread among his troops, who believed only he could lead them home. Finally, to calm the fearful men, the recovering Alexander was put on a boat and floated down the river for all to see.

Continuing downriver to the Arabian Sea, Alexander sent part of the mixed multitude homeward by ships along the coastline. Since there were not enough boats for everyone he personally led the remainder on a miserable march across the Baluchistan desert. Suffering was quick and intense as soldiers soon exhausted their reserves of food and water and were compelled to butcher their pack animals for food, and then burn their baggage and wagons to keep warm during bone-freezing nights. Without a means of transporting their plunder, most of it was abandoned.

The merciless desert with its killing temperature extremes between day and night was an enemy even this peerless horde could not fight. Thirst was the main problem. Sensing their leader was nearing the end of his tether his men, at one point, took up a collection from their dwindling canteens and collected a helmet-full of water which they gave to him. With tears in his eyes he poured it out to signify he would suffer the same as them. They were as touched as he was. According to the historian Arrian, who accompanied the expedition, Alexander “poured it out in the sight of all. The army was so much heartened that it seemed every man had drunk.”

Too much water soon became a problem as a flash flood struck the lengthy column, carrying away most of the camp followers while the troops barely escaped. Managing to reach the city of Bampur, the Greeks found food, water and momentary rest. Anxious to make it home they quickly headed for Persepolis, where Alexander found the occupation government he had installed in disarray. The Persian and Greek governors he had appointed had not expected him to return and were greedily overtaxing the populace and embezzling from the coffers. After executing these thieves and appointing new civic leaders he pressed on to Susa and took a major step toward assimilation of his empire’s population.

He organized a mass wedding in which 10,000 of his men married Persian women, and 80 of his senior officers married Persian princesses. After giving all the nuptials lucrative dowries and with Roxane at his side he married Darius’ daughter, Princess Barsine, as a second wife. As ambitious as ever, he laid plans for further expansion. He dispatched ships to reconnoiter the coastlines of Saudi Arabia and Africa, the marshland along the Iran-Iraq border, and to sail up the Tigris all the way to Opis. Between his own flagging health and his army’s disillusionment both with the endless campaign and with their leader’s increasing adoption of Persian ways—outside his pavilion they chanted, “Send us all home. You can campaign with your father Ammon”—his soldiers furthermore suspected he considered himself a god. They did not agree, and there would, in fact, be no more crusades.

Plagued by desertions, Alexander led his remaining soldiers into Babylon in the spring of 323 B.C. The arrow that had struck him in India had pierced a lung, and the wound had not healed. Added to this injury was his overdrinking, the strain of the past decade and a fever he had contracted in Susa. He could sense he was dying. Word quickly spread to his soldiers, who demanded to see him.

Too weak to stand or even sit had had himself propped up with pillows on a couch in his pavilion. For the next several hours his soldiers filed past him. He acknowledged every man with a word or a nod. He died the next day. Despite his untimely passing at 32 he achieved his stated purpose. “I set no limits of labors to a man of spirit, save only that the labors themselves lead on to noble enterprises,” Arrian recorded. “It is a lovely thing to live with courage, and to die leaving behind an everlasting renown.”

His empire encompassed one and a half million square miles, but without him it did not last long. The implications of his having lived longer are sobering. On the banks of Italy’s Tiber River a new realm called Rome was making its first stirrings. Eventually it would absorb tottering Greece, and at the same time be profoundly influenced by it and by the truly Great Alexander.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments