By Dr. Forest Issac Jones

The heroics of African American soldiers during the D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, have not been taught regularly in high school or college history classes.

The Hollywood blockbuster Saving Private Ryan did not depict any African American soldiers being present that day. The film did show some barrage balloons aloft on Omaha Beach, but did not mention who operated them. When soldiers who were being celebrated in France for the 65th anniversary of D-Day met actor Tom Hanks, he said he had no idea that African American soldiers and the 320th Battalion were there. The soldiers of the 320th had to overcome segregation, racism, and the notion among many military leaders that African Americans were not fit for frontline military service. In Normandy, the men of the 320th worked diligently to protect American troops and ships offshore.

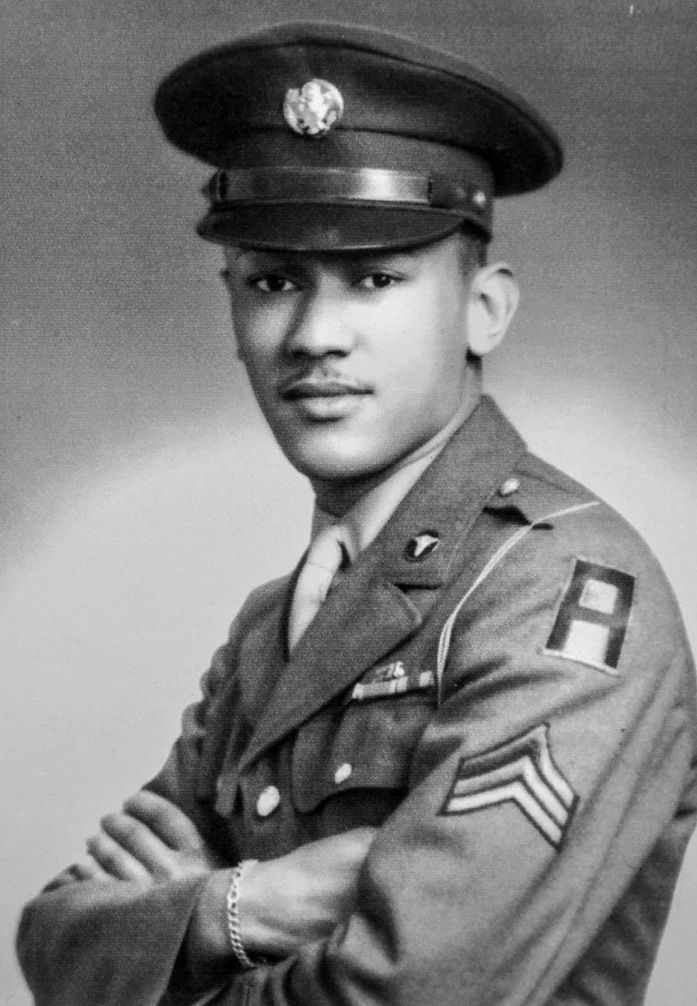

William G. Dabney was one of those men in the 320th Battalion who created their legacy on the beaches of Normandy. Dabney sat for an interview in October 2018; he was 94 years old, and he had a lot to talk about when it came to the African American soldiers’ role on D-Day, a role that had been ignored by books, movies, and most historians. Most historians thought that African American soldiers were only there to do menial jobs in the broad context of the D-Day invasion.

Dabney was awarded the French Legion of Honor (Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur) for his actions during the D-Day invasion. At the time of the interview, he was one of the last known surviving soldiers from that battalion, which was the only all-black unit involved in the D-Day landings.

The author sat down with Dabney in his home in Roanoke, Virginia. He was a straight-shooter with a wicked sense of humor. Throughout the conversation, he shrugged off the casual racism that he had endured during his military days and focused, instead, on his contributions during the D-Day invasion. His account provided a wealth of knowledge. He was more confident in telling his story after years of people not believing that he was part of the invasion of Normandy.

“I didn’t talk about it because nobody would believe me,” he remembered. “I’d play pool with friends, and I’d talk about the army and D-Day invasion and my friends told me to cut it out, that I hadn’t been anywhere. So, I just stopped talking.”

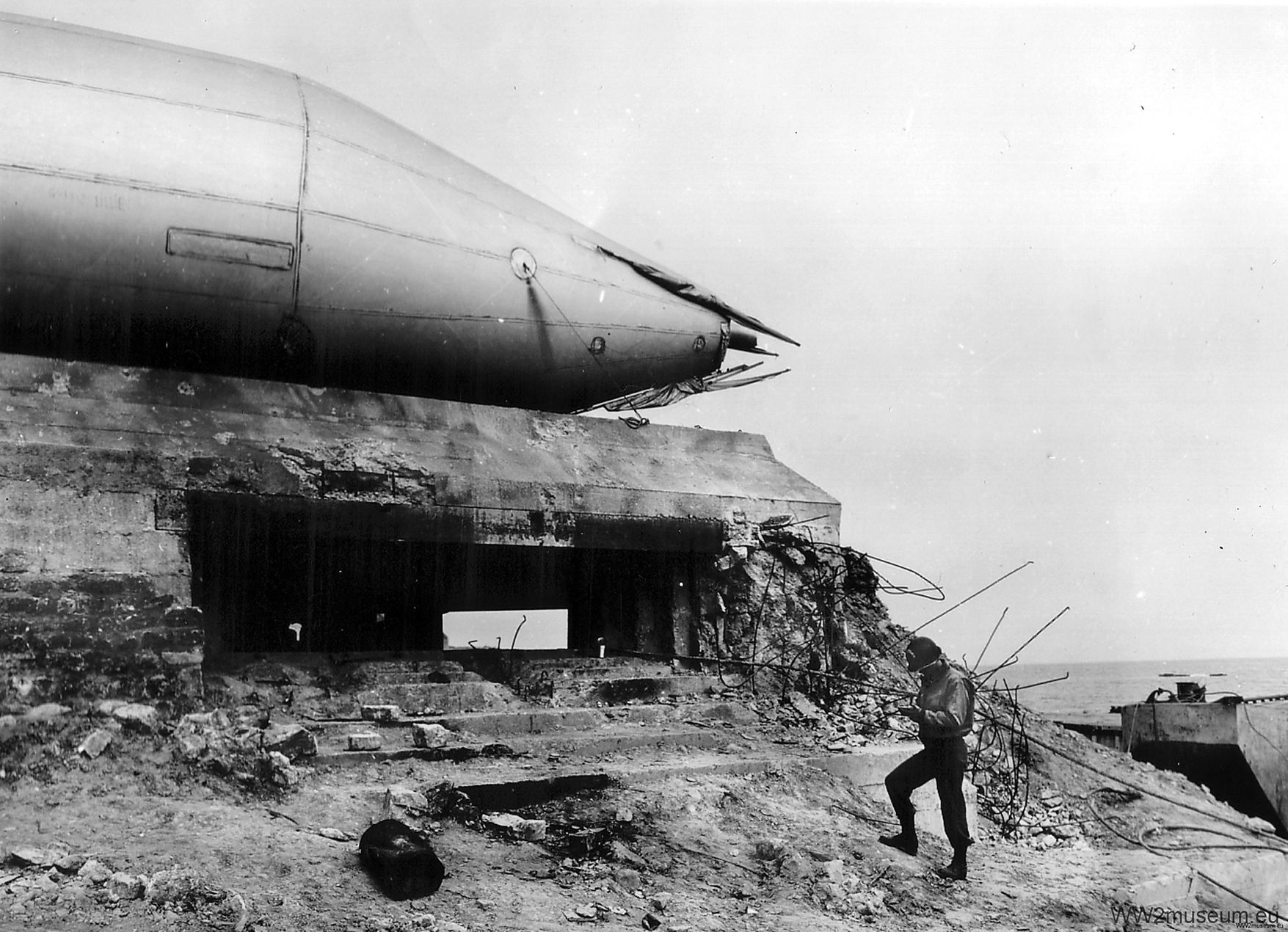

The African American 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion began landing on the beaches of Utah and Omaha by 9 a.m. on June 6, 1944—just two hours behind the first wave. The only African-American combat unit to land in France on D-Day, the well-trained battalion was tasked with operating the balloons to protect the U.S. soldiers from attacking Luftwaffe aircraft. Inflated in England and tethered to the landing craft, the balloons destined for Omaha were all destroyed before landing. At Utah, some 20 balloons made it ashore where they were ordered cut loose by commanders concerned that they were drawing enemy fire. By about 11 p.m., the 320th had one balloon up, with another 11 flying by dawn but German artillery knocked them out the next day. The unit was quickly resupplied and the balloons were back up.

Their balloon cables were intended to ensnare the wings and propellers of German aircraft. Some 140 balloons would be up over Omaha and Utah beaches by June 21.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, thrust the United States into World War II and changed American society in many ways. Record numbers of African Americans enlisted to serve their country. They saw it not only as a chance to show Americans that they could fight for their country, but they also saw it as a chance for racial respect in their own hometowns.

At the time, segregation and Jim Crow were still standards throughout the South, and the military was no different. There were still questions concerning the capabilities of African Americans fighting in the military. Even though these beliefs still remained in society, African Americans had fought bravely in both the Civil War and World War I. However, African Americans were still not seen as equals to white soldiers.

During World War II, more than a million African American soldiers would serve their country. The soldiers of the 320th were among them, and many people such as Dabney would end up at Camp Tyson near Paris, Tennessee, to learn the trades of warfare. Dabney and many others trained at the army base in 1942 and 1943.

Camp Tyson was the first base in the U.S. created primarily to teach soldiers how to fly barrage balloons. There were approximately 30 barrage balloon battalions trained at Camp Tyson prior to D Day, with the 320th being the only all-black barrage balloon battalion. Each battalion consisted of approximately 42 officers and 1,100 enlisted men.

Lieutenant Colonel Leon J. Reed, a white officer from South Carolina, was placed in command of the 320th, and he earned the respect of the men. The African American soldiers did basic training first, and it was strict to make sure they were in fine condition. After that was completed, they started six weeks of training with the barrage balloons. The soldiers learned how to carefully fill the balloons with hydrogen gas and how to maintain and deploy them during wartime.

After the 320th finished its balloon training, the soldiers learned how to forecast the weather. They had to be careful controlling the 35-foot balloons, and the training taught them how to anticipate and deal with varied weather conditions.

When the training was finished, the 320th Battalion headed for ships that would take them to England. The unit arrived on November 24, 1943. Dabney and his colleagues were warmly welcomed by the locals. He mentioned plenty of dances, social occasions, and being treated as equal citizens in both the community pubs and in the streets.

As the men of the 320th enjoyed their time in England, they also prepared for the invasion of Europe that was on the horizon. They had taken smaller balloons with them from Camp Tyson, and these were called VLAs (Very low altitude). The British-designed VLAs could be safely tied to boats and vehicles, and they could reach altitudes of 4,000 feet or more, close to the ceiling of the larger balloons that the 320th had originally used.

There were about 600 men in the 320th on English soil, and there were more than 130,000 African American soldiers in the United Kingdom. The men of the 320th were moved across England and Wales to train for the Normandy invasion. They were working to prepare the balloons to be available early on D-Day. The VLA was designed so that one soldier could carry the winch that would send the balloon up in the air.

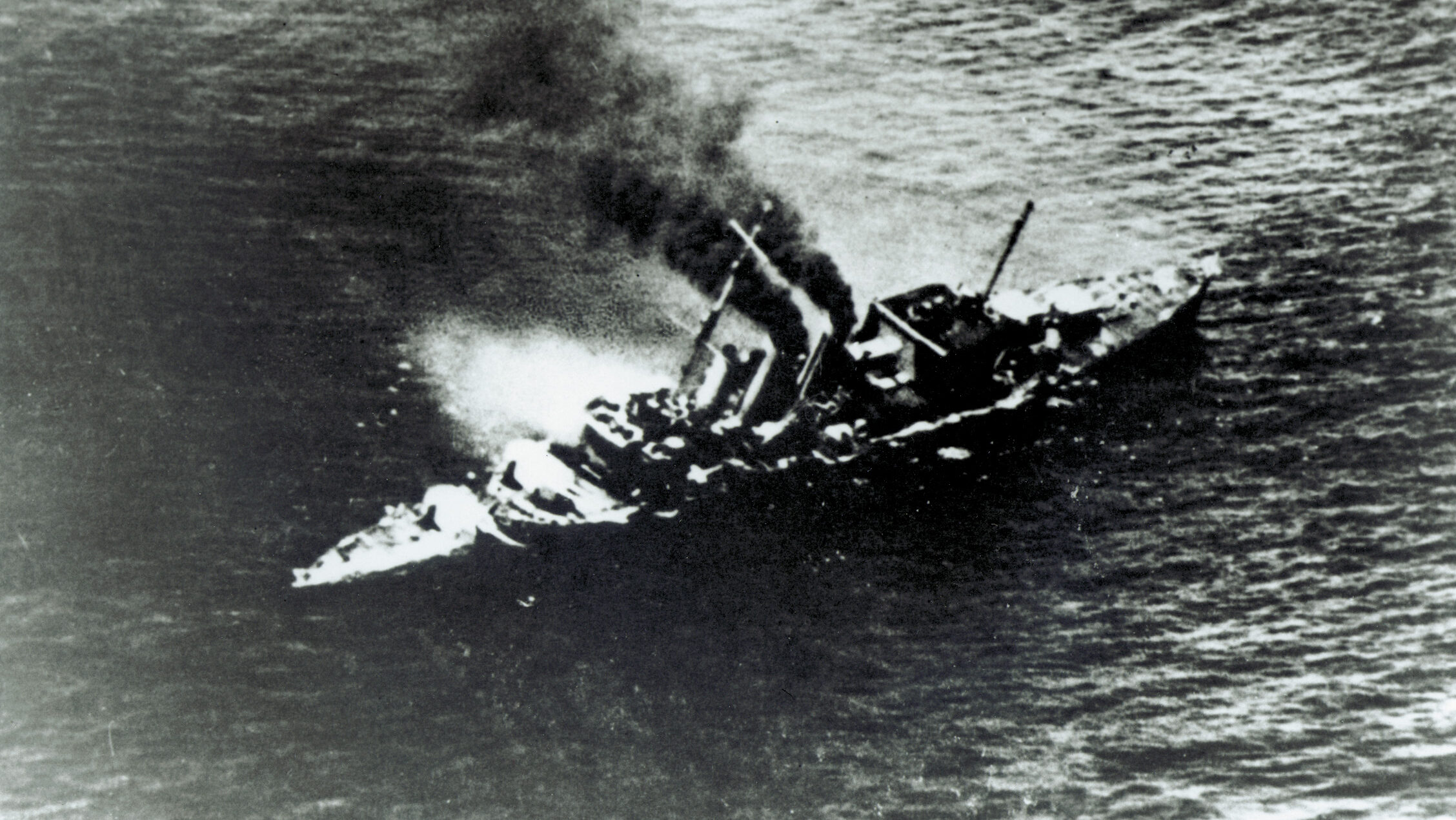

The job of the 320th was simple on D-Day—to protect the ships and other craft offshore, as well as the combat troops on the beaches, from German planes that might strafe and bomb them. The men of the 320th moved the balloons into the most advantageous locations to dissuade the German pilots from making passes at the targets below. The balloons also augmented the firepower of Allied antiaircraft guns aboard the ships off Omaha and Utah beaches, as well as those later brought ashore.

The balloons were inflated while the 320th was still in England and attached to the ships that took part in the voyage to Normandy. Separated into groups of four or five men, the 320th was to move the pre-inflated balloons from the ships to the beaches.

It was a dangerous job. The soldiers working with inflated balloons served as anchors to maintain control in windy conditions. The 320th knew when to send the balloons up and when to take them down. Soldiers like Dabney were warned when enemy aircraft were airborne. When there were no enemy planes in the air, the battalion would send balloons up in an effort to deter the Nazis from taking to the sky.

The majority of the soldiers in the 320th were headed to Omaha Beach on D-Day, where planners believed enemy small-arms and artillery fire would be intense, along with the probability of attacks by the Luftwaffe even though Allied air forces had won air superiority in Europe during the preceding months.

Dabney was one of those first men ashore, in charge of three others with the balloons ready to protect the soldiers. They got their balloons in the air as quickly as possible, even as the Germans continued to resist. More balloons came across the Channel from England on June 6, already inflated and ready for deployment.

“My job on D-Day was to take the balloons…and to protect and keep the planes from coming in on the soldiers,” he said. “The purpose of flying the balloon was to stop any plane that might strafe the beach to kill the soldiers. The plane couldn’t see the cable because it was thin,” he continued. “Depending on where they were flying, the balloons helped the antiaircraft people.”

The young men would grab the mooring lines hanging from the balloon, one on each side, and draw them in to be tied down. High winds could cause trouble with the lines, whipping them with such force that they became dangerous when out of control.

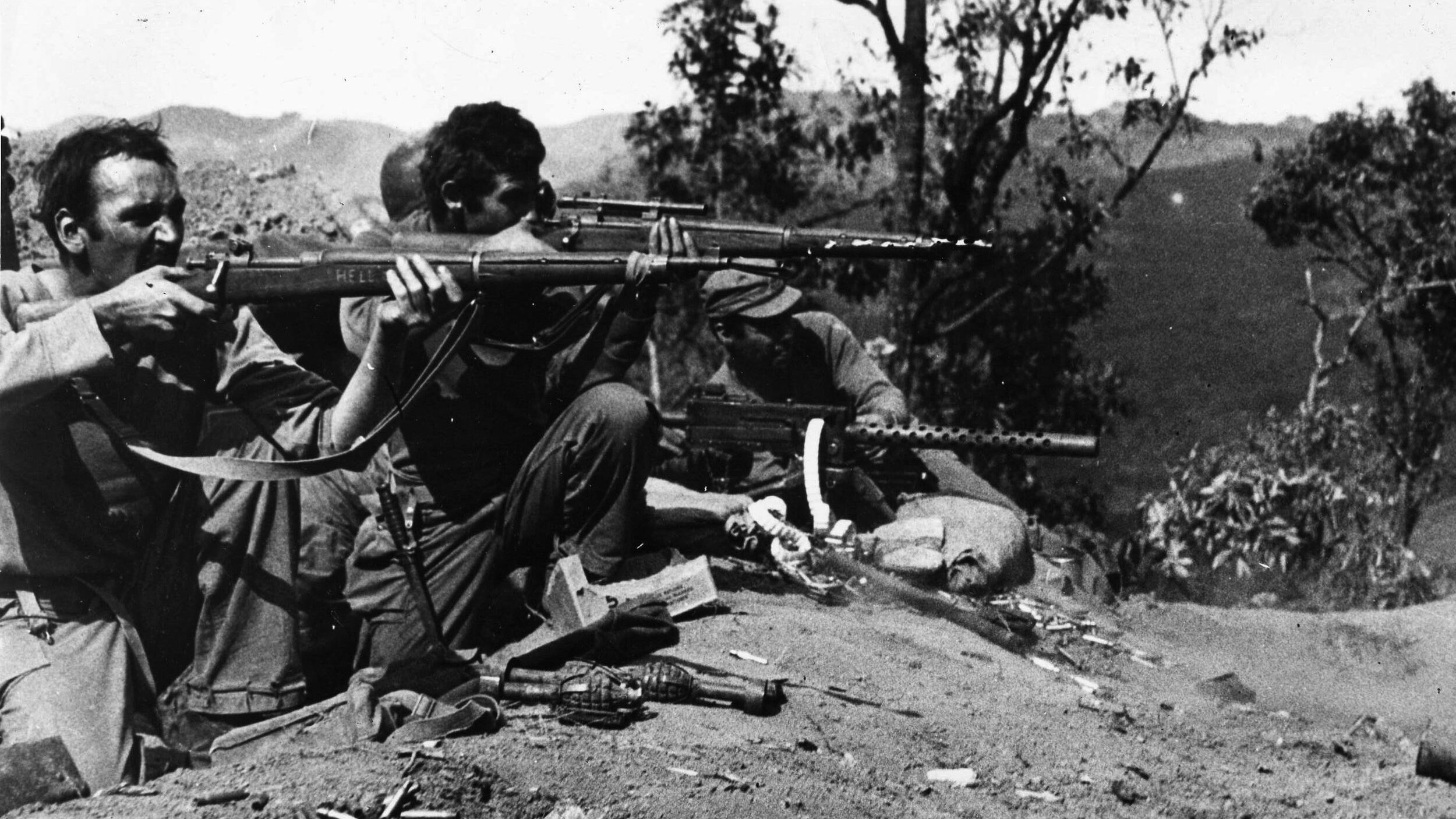

When the 320th hit the beaches, the heavy surf and high winds made coming ashore difficult. Some landing craft disgorged their human cargoes in water that was quite deep. One balloon was seen going down, but the men of the 320th were unsure whether it was German fire or friendly fire that caused that first casualty among their much-needed equipment.

“When we started the invasion, the commanding officer said some of us wouldn’t return, some of us would die,” Dabney recalled. “We climbed on the ship, stayed in the Channel, waited for air [cover], crawled down ladders, landing [craft] boys came, water was splashing, and we went across the English Channel. It was rough water. The tide was still coming, and the weather was rough for the ships. The English Channel could get rough and it was rough when we landed. Imagine that, getting off the boat, wading to shore with the Germans shooting.”

The soldiers of the 320th exited their landing craft and waded to shore under enemy fire. There was no time to be afraid. Too much was happening around them. Hours went by before the American foothold at Omaha Beach and the advance from Utah Beach had caused enemy fire to slacken. The silver, oval-shaped balloons were a strong defense barrier for the soldiers fighting their way off the beaches. The protective line of balloons flew in an unorthodox pattern, forcing any German pilot to fly at higher altitudes, thus discouraging attacks on the forces below. Forcing enemy planes to fly higher also made them easier targets for American antiaircraft guns. The balloons were especially effective against enemy planes at night when the cables were difficult to see.

Henry Parham, another member of the 320th, described what he saw when they first landed. “We landed in water up to our necks,” he told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “Once we got there we were walking over dead Germans and Americans on the beach. Bullets were falling all around us.”

Men from the 320th remembered that the scene was a mess at Omaha Beach. The 320th faced a heavy dose of machine-gun fire from the Germans. A number of the balloons were shot up and destroyed before they could be taken off the ships. Many of the soldiers were cut down by enemy fire and men of the 320th had to drop down and pretend they were dead to survive. Some crawled from one dead soldier to another to protect themselves until things had cooled down on the beach.

Most of the 320th landed at Omaha Beach, where Lieutenant Colonel Reed could barely find his soldiers amid all of the shooting. He saw that they had trouble getting some of their equipment off the boats successfully.

Dabney talked about how he and the rest of the 320th remained dedicated to their task, protecting the soldiers landing on the beach, despite the chaos that surrounded them. “My biggest job in the Army was to fly that balloon,” he said. “It was a live balloon, and you are the live anchor man.” The standard balloon crew was normally five men, but the 320th reduced crews to three and four, specifically for the D-Day invasion.

The 320th had to make sure that the barrage balloons were in the air before nightfall because they believed that a German air attack might materialize after the sun went down. Finally, the 320th Battalion got 12 balloons in the air by D-plus One. The Germans continued to go after the balloons but by the evening of June 7, there were as many as 30 of them over Omaha and Utah beaches. Over the next couple of months, the balloons helped protect ships and soldiers. In all, the African American soldiers protected the Allies on Normandy for close to 150 days.

Parham talked about the experience on the beaches during the invasion. “Staying in your trench was the hardest thing,” he said. “It was two months of ducking and dodging and hiding. I was fortunate that I didn’t get hit. I managed to survive with God’s strength and help.”

Psychologically, the most difficult part of D-Day, Dabney said, was dealing with the terrible casualties. “When our soldiers had cleared all the Germans away that morning, there was nothing but dead bodies on the beach,” Dabney said. “The soldiers had two dog tags, one to the undertaker, and one stayed on the soldier at the morgue until he was identified. That’s what they were doing that morning. They were picking up the bodies and taking the dog tags. As the invasion continued, you couldn’t bury each soldier individually, you had to put the bodies in a ditch for the time being. There were too many of them.”

After the Allied victory at Normandy, it appeared that Dabney and the 320th Battalion would see action in the Pacific theater. “When we came back from France after the invasion, we came back home, stayed 30 days, and then shipped out to Washington state,” he said. “That meant you were going down under, to Australia or to the Philippines to fight. We crossed the Pacific, and something happened to the boat. It needed service. We got to Hawaii, and they announced the war was over. We didn’t have to fight. We stayed in Hawaii for six months, came back to California, and went home.” At the age of 22, Dabney joined other men of the 320th in finally returning home for good.

Dabney and the other African Americans in the 320th battalion were a great example of the courage, bravery, and determination that was needed on June 6, 1944. There were naysayers that did not believe African Americans had the courage to fight, but these men went on to prove those negative people wrong.

After the war, Dabney lived in Roanoke without much fanfare about his service and participation on D-Day. He lived quietly and worked as the owner of a carpet-laying business for years without commenting on his heroics during World War II. He met his wife, Beulah, in 1948 when he was a sophomore and she was a freshman at St. Paul’s College. “We met on the bus going to school after the Christmas holidays,”she said. “We dated the whole time while I was in college. He finished a year ahead of me and I graduated in 1951 and we got married that year.”

Unfortunately, the 320th Balloon Battalion did not immediately receive the recognition that it deserved for its contribution to the success of the D-Day. There were no celebrations or stories about what they did on D-Day—their heroics simply disappeared. They came home to an America that continued to be segregated, despite efforts by African American veterans to fight for Civil Rights. Dabney and others in the 320th admittedly said they remained quiet for years about the barrage balloons because nobody would believe them. If it were not for historians that dug deep and talked to eyewitnesses, their stories would not have seen the light of day.

The actions of the 320th began to come into the public view after a man named Sam Wooten contacted Dabney and others in the battalion about their experiences at Normandy. Wooten, who had a French mother and African American father, grew up in France, but lived in San Francisco, California, at the time. He had noticed that white soldiers were routinely present when D-Day celebrations took place in Normandy, but African American soldiers had never been included.

Wooten and his mother decided that they would sponsor an African American soldier who was involved in the D-Day invasion to attend an observance in Normandy. Through a contact, Wooten was able to find Dabney and invited him to France at Wooten’s expense, where they would film a documentary about the 320th Battalion.

“This is what got the word spread about my involvement,” Dabney said about the visit to France. “When I was in France I stayed with private families for two weeks there, and the families treated me well. They treated me like one of the family, all during the documentary. They were very nice people and treated me kindly.”

As a result of Dabney’s newly found recognition, he was presented with the French Legion of Honor on the 65th anniversary of the D-Day invasion in 2009. While he was in France, Dabney also met President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, former President George W. Bush, and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, as well as other dignitaries. He remembered that the scars of war seemed to have disappeared.

“They had cleaned up the place so nice that a lot of the places you wouldn’t even believe that it was bombed. I got up and shook [President] Obama’s hand, and he said, ‘Dabney, I know who you are.’”

Waverly B. Woodson, Jr., a 320th Battalion medic, received the Bronze Star for valor under fire in Normandy. “D-Day was the most emotional and dangerous day in my life,” he remembered. “As a young soldier far from home, the assault units waited patiently to begin their mission. Everyone knew the first 24 hours would be critical to the course of the war.”

Along with Woodson, three other medics from the 320th—PFC Warren Capers, Corp. Eugene Worthy and Staff Sergeant Alfred F. Bell—set up a dressing station and aided more than 330 soldiers on a beachhead on D-Day. Capers was recommended for a Silver Star.

Henry Parham, who received the French Legion of Honor in 2013, died at 99 in July 2021. “I did what I was supposed to do as an American,” Parham said about his D-Day participation. “I managed to survive with God’s strength and help. I prayed to the good Lord to save me. I did my duty.” In his later years, Parham had spoken to many organizations and civic groups in his home state of Pennsylvania about his war experiences.

“When we invaded, I didn’t think I’d come out alive,” Dabney said. “The way the gunfire lit up the beaches, I won’t be standing when it’s over. The Lord was with me.” He was wounded in the leg during the opening moments under fire at Omaha Beach, but he bandaged it, carried on, and did not mention it to anyone. He died quietly in Roanoke on December 12, 2018.

The story of the 320th Battalion is one of dedication, perseverance, and at long last, recognition that continues to resonate today.

Dr. Forest Isaac Jones, an educator and author, resides in Salem, Virginia. He writes on a variety of topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments