By William E. Welsh

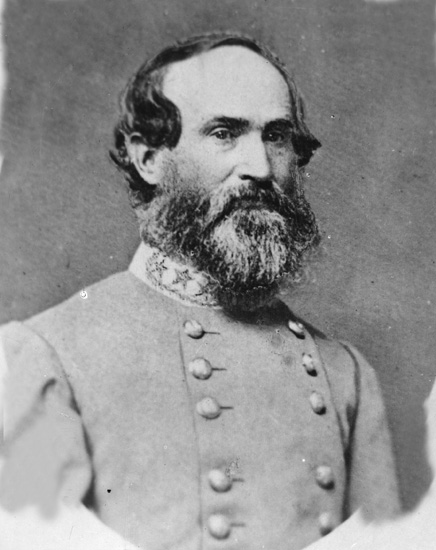

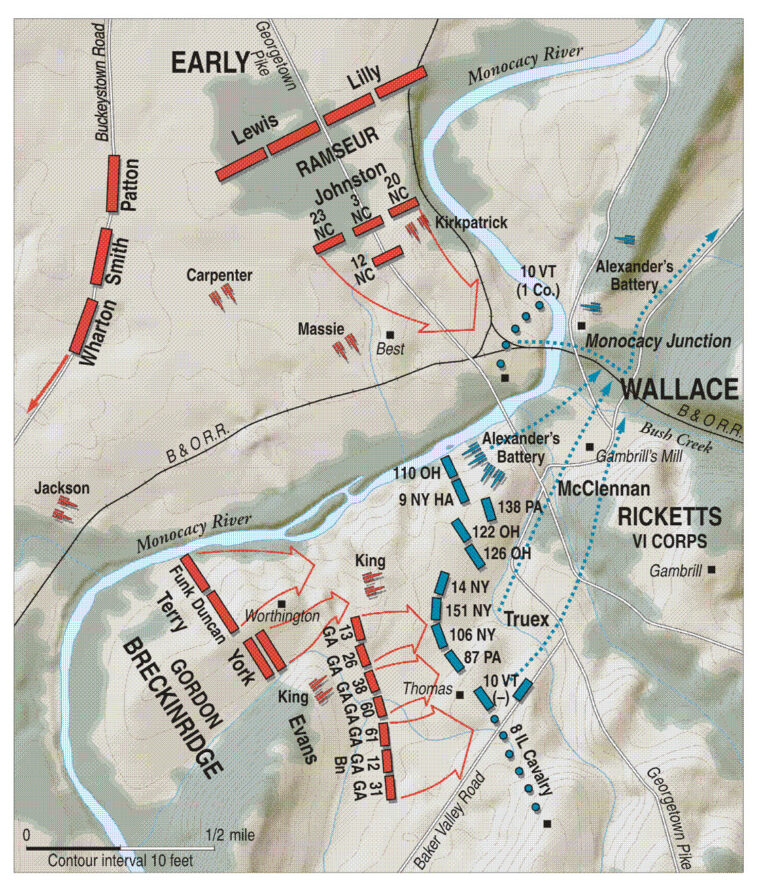

Major General John Brown Gordon guided his horse past fields where stalks of waist-high corn glistened in the sun. About 15 minutes earlier he had watched as the foot soldiers at the head of his 3,500-strong division strode fully clothed into a shallow ford in the Monocacy River. Having told his three brigadiers to get their troops across the river as quickly as possible, Gordon rode at mid-afternoon on July 9, 1864, through the ford and spurred his horse up a steep grade on the east bank. He wanted to survey the Yankee position and determine how best to drive the bluecoats from the field.

Gordon rode across John Worthington’s farm toward an adjacent farm to the north where the Federals were waiting. On the way, the Georgia-born general passed dismounted Virginia cavalry that had found the ford that morning but failed to drive the Yankees from the Thomas Farm. Rifles cracked and minié balls whistled through the air as the two sides exchanged fire.

A hill not far from the Worthington house afforded Gordon a wide view of the battlefield across which he would send his infantry against the enemy. The Yankee line was situated on a low ridge about a half mile from where Gordon was making his reconnaissance. The Georgian noted that the bluecoats were posted behind fences for protection and that their line of battle ran from high ground on his right to the river on his left. A Yankee battery next to the river was posted to sweep the farmland. Farther back, the Yankees had a second line of troops in support. Both lines were south of Georgetown Pike, which led east from Frederick, Maryland, to Washington.

It took only minutes for Gordon to form his plan. His brigades would form up in a protected area behind a wooded hill on the southern end of the Worthington Farm. The Butternuts would cross the hill and debouch from the woods onto open fields. Gordon’s line would overlap the enemy’s left flank. If everything went well, his soldiers would roll that flank up, forcing the enemy to retreat.

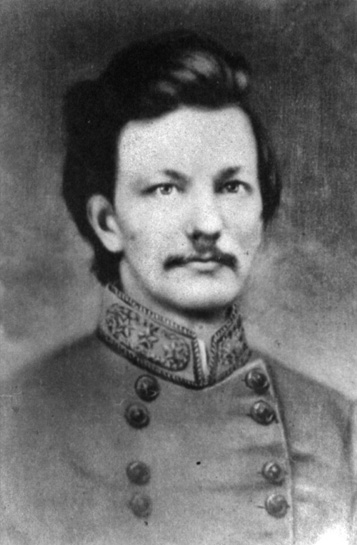

Gordon’s brigades would attack by echelon, beginning with Brig. Gen. Clement Evans’s Georgia Brigade on the right, followed by Brig. Gen. Zebulon York’s Louisiana Brigade in the center, and Brig. Gen. William Terry’s Virginia Brigade on the left. Confident of success, Gordon turned his horse back to give final orders to his brigadiers and, as was his custom, to help guide the troops into battle.

Gordon knew that the Yankees had to be pried from Monocacy Junction before dusk so that Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s 12,000-man army could continue its raid on the Federal capital at Washington. The longer that Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace’s scratch army delayed Early’s army, the more likely that the fortifications at Washington would be manned by Union veterans transferred by boat from the Richmond-Petersburg sector when the Confederates reached the city. Time was critical, and Gordon intended to make quick work of Wallace’s Yankees.

At the beginning of June 1864, the Army of the Potomac, led by Maj. Gen. George Meade and accompanied by General of the Army Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, had slowly advanced after a month of hard fighting to the outskirts of Richmond. Lee had miraculously managed through the skillful use of maneuver and field fortifications to keep Grant from fighting his way into Richmond. But a new threat had developed in the form of Maj. Gen. David Hunter’s Army of the Shenandoah, which was marching on Lynchburg, bent on destroying the railroads of central Virginia that supplied Lee’s army.

Lee dispatched Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge with his 2,100-man division from Richmond on June 7 to resist Hunter’s advance on Lynchburg, but when word reached Lee that Hunter’s 9,000-man Army of the Shenandoah was scheduled to double in size when reinforced by Brig. Gen. George Crook’s Kanawha Division, he sent 47-year-old Lt. Gen. Jubal Early with an entire Confederate corps to join Breckinridge.

On June 12, Early left Richmond at the head of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Second Corps, comprising 12,000 men in three divisions and two battalions of artillery. Early reached Lynchburg before Hunter. When Old Jubilee attempted to bring him to battle, Hunter shamefully withdrew into the Allegheny Mountains.

At that point, Lee ordered Early to launch a raid on Washington to siphon troops from the Army of the Potomac operating against the Confederate capital. It was Lee’s hope that Grant would be forced to send a sizable portion of his army by water from the James River to Washington to defend the Federal capital. Early knew it was a risky operation. His small army might be attacked before it reached Washington, and even if it did make it to the outskirts of the strongly fortified capital, it was likely that it could do little damage. Nevertheless, the Army of Northern Virginia was hard pressed, and Lee was willing to take a major gamble in an effort to disrupt Grant’s strategy.

For the campaign, Early reorganized his forces into two corps of two divisions each while encamped at Staunton, Virginia. One of the corps was led by Breckinridge, and the other corps by Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes. Rendezvousing with Early to support his march north were four brigades of cavalry under Maj. Gen. Robert Ransom.

Early’s army marched north from Staunton on June 28. Lee had also instructed Early to disrupt the Federal communications and transport infrastructure wherever possible on his march. To get a head start on these objectives, Ransom’s cavalry had ridden north to destroy sections of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

Early’s vanguard made contact on July 3 with the Federal garrison under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel at Harpers Ferry. After some protracted skirmishing, Sigel on July 5 withdrew his four regiments to a strong defensive position on Maryland Heights. Because Sigel’s guns on Maryland Heights dominated the surrounding terrain, including the town, Old Jubilee deemed it impractical for his troops to occupy the abandoned town. Instead, the Confederates made preparations to cross into Maryland west of Harpers Ferry. On July 6, Early’s troops splashed through Boteler’s Ford and entered Maryland.

Word had quickly arrived in Baltimore and Washington that a rebel force of unknown size was moving through the Shenandoah Valley. The initial warning was sounded by B&O Railroad President John W. Garrett, who had received reports on June 29 from railroad agents that the Confederates were destroying B&O property between Harpers Ferry and Cumberland.

On July 2, Garrett sought out Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace, who commanded the Middle Department, which was responsible for the upper Mid-Atlantic States. Garrett, who stopped by unexpectedly at Wallace’s headquarters in Baltimore, requested that Wallace dispatch troops to protect the railroad between Harpers Ferry and the Monocacy Junction. The junction, situated on the west bank of the Monocacy River, was the point at which a spur of the B&O Railroad ran north to Frederick. Wallace told Garrett flatly that he had no authority west of the Monocacy River.

Garrett insisted that at the very least Wallace should take immediate steps to protect the railroad bridge over the Monocacy River, which was a vital piece of infrastructure. Two blockhouses, one on each bank, were occupied by guards, but Wallace decided to strengthen the junction immediately by sending Colonel Charles Gilpin’s Third Maryland Potomac Home Guard Brigade (a regiment-sized unit) to bolster the defenses at the junction. Gilpin’s unit, which was one of five regiments in Brig. Gen. Erastus Tyler’s First Brigade of Wallace’s VIII Corps, was the first unit to reach the junction.

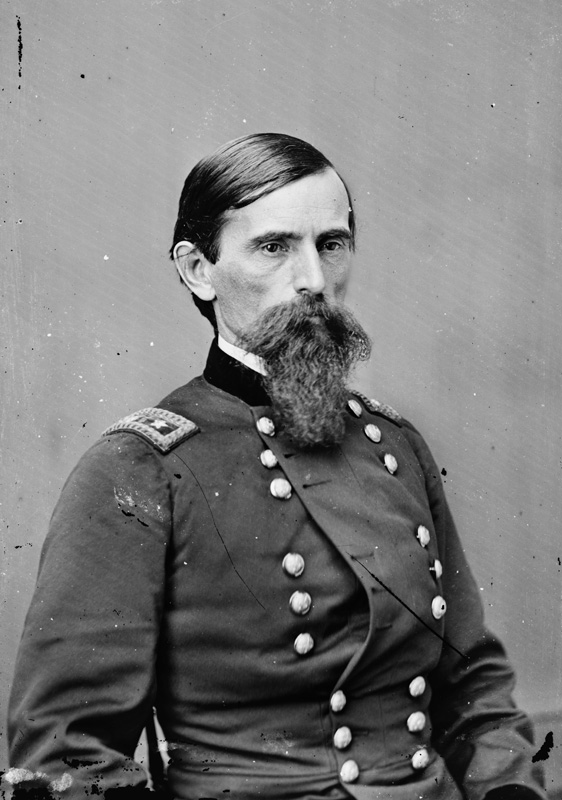

Union Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck in Washington briefed Grant by telegraph on July 3 about the unfolding crisis. Grant insisted that Early’s corps was still at Richmond. But Grant was dead wrong. To put Halleck’s mind at ease, Grant told Halleck to order Sigel to intercept the mysterious Confederate force. Halleck complained that most of the troops available to defend Washington were militia. To appease Halleck, Grant said that if necessary he would send Brig. Gen. James Ricketts’s 5,000-man Third Division of the VI Corps north by water to Baltimore.

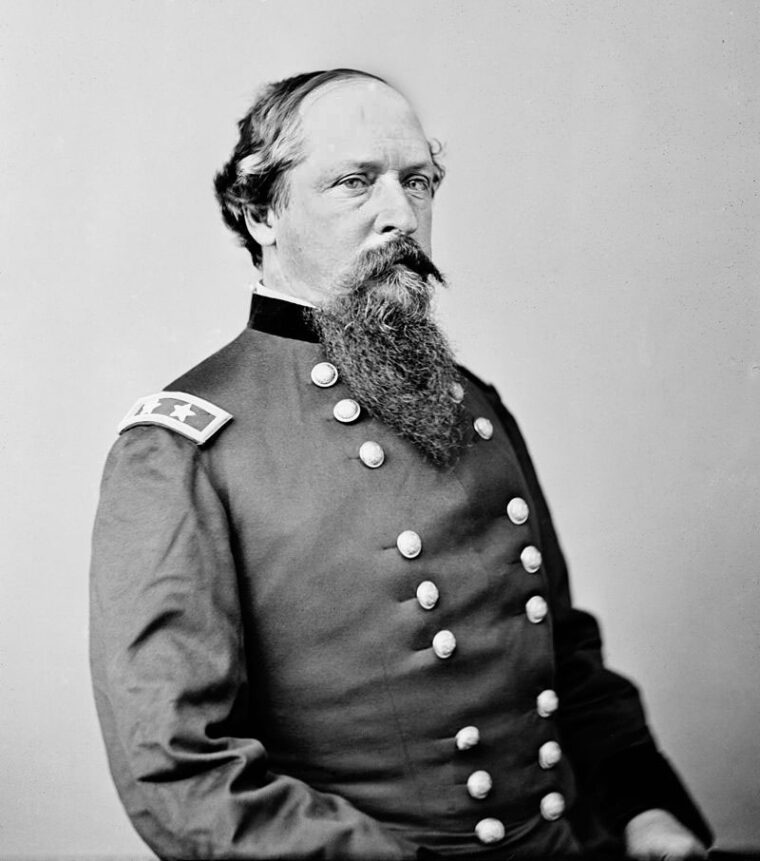

Wallace, who had led a Union division at Shiloh in April 1862, had performed poorly on the first day of the battle and been made a scapegoat in its aftermath. But he was a staunch Republican, and in March 1864 Lincoln appointed him to command the Middle Department.

Wallace immediately began shifting forces west to protect the junction and made plans to be there himself to oversee its defense. Unfortunately for Wallace, Halleck could not get help from either Sigel or Hunter, both of whom avoided communications with Washington. Both would eventually be replaced.

On July 6, Wallace accompanied the balance of Tyler’s First Brigade of the VIII Corps to Monocacy Junction. This included Captain Frederick Alexander’s Baltimore Artillery composed of six 3-inch rifled cannons. A boon to Wallace was the unexpected arrival at the junction of five companies of Lt. Col. David Clendenin’s 8th Illinois Cavalry totaling 230 men armed with Sharps carbines. Halleck had sent Clendenin’s horse soldiers from Washington to protect the telegraph lines and gather information on the Confederates. By the end of the day, Wallace had about 2,300 men at Monocacy Junction, but most of them were green troops.

On July 8, the main body of Early’s army marched through the gaps in South Mountain. Wallace had received a dispatch from Garrett the day before that a large force of Union veteran infantry had arrived by ship in Baltimore and would begin arriving the next morning to reinforce Wallace.

Wallace issued orders for Gilpin’s brigade and also for Colonel Allison Brown’s 144th and 149th Ohio Regiments to cover the Stone Bridge (21/2 miles north of the railroad junction), which carried the National Pike from Frederick to Baltimore. This was necessary to protect the right flank of the troops at the junction and maintain communications with Baltimore.

At Monocacy Junction itself, Wallace prepared to defend a covered wooden bridge that carried Georgetown Pike from Frederick to Washington, as well as the iron railroad bridge that Garrett was so concerned about. Earlier in the war, the Union had erected two blockhouses, one at the railroad junction on the west bank and one on the east bank. The two-story blockhouses were made of massive logs and had narrow slits through which the troops inside could fire on any attacking force. Near the blockhouse on the east bank, which was situated on the north side of the railroad, a 24-pounder howitzer posted on the bluffs provided some artillery protection. Unfortunately, the gun would jam halfway through the battle.

William Truex’s 1st Brigade of Ricketts’s division began arriving by rail at Monocacy Junction on the morning of July 8. After some heavy skirmishing by a portion of Wallace’s command and Confederate cavalry in Frederick that day, Wallace made assignments that evening for the battle he expected to occur the following day. The future author of Ben-Hur instructed Clendenin to deploy his command at river crossings downstream from the junction, including the Worthington-McKinney Ford. Wallace gave Tyler command of the right wing. As for the two bridges directly east of the junction, Wallace planned to rely on Ricketts’s sturdy veterans to oversee their defense. At 8 pm, Wallace sent the following message to Halleck: “I shall … put myself in a position on the road to cover Washington, if necessary.”

Another train arrived with additional reinforcements at 1 am on July 9. The train carried Colonel Matthew McClennan’s 2nd Brigade of Ricketts’s division, and it also bore the divisional commander. Wallace suggested the forces assembled march west in an effort to join forces with Sigel’s command at Harpers Ferry, but Ricketts dissuaded him of the idea. “What! And give Early a clear road to Washington,” Ricketts said. “Never! We’ll stay here. Give me your orders.” Wallace explained that he intended to put a token force on the west bank to delay the Confederates as long as possible. He ordered Ricketts to deploy his men in two lines on the east bank to receive the attack that was expected the following morning.

A storm swept through the area that night, drenching gray and blue alike. After it was over, the temperature dropped noticeably, and the soldiers of both armies were awakened by roosters crowing in the barnyards of the farms located in the lush river valley. “The sun was bright and hot, a nice breeze was blowing which kept us from being too warm,” wrote First Sergeant John Worsham of the 21st Virginia Infantry of Terry’s Consolidated Virginia Brigade. Union soldiers also noted the spectacular weather. “The clouds dispersed early this morning and the sun came out warm and beautiful,” wrote Sergeant William James of the 11th Maryland Volunteer Infantry of Tyler’s brigade.

Rodes’s corps marched unopposed through Frederick shortly after daybreak on July 9 with Maj. Gen. Stephen Ramseur’s division forming the vanguard. Ramseur advanced cautiously on Georgetown Pike toward Monocacy Junction, while Rodes led his own division east on the National Pike toward the Stone Bridge. Leading the advance toward Monocacy Junction was Brig. Gen. Robert Johnston’s Brigade, which comprised four North Carolina regiments. As a line of Tarheel skirmishers fanned out on both sides of the road at about 8:30 am, Captain Thomas Kirkpatrick’s Amherst Artillery unlimbered two 3-inch ordnance rifles on a small hillock behind them. The Rebel guns immediately began shelling the Federals to the east.

Alexander’s Baltimore battery had been divided into two parts with three guns sent to support Ricketts’s left on the 260-acre Thomas Farm to the south and the other three positioned on Ricketts’s right opposite the junction. The Federals responded quickly, and the Confederates soon moved other batteries up to support Kirkpatrick, namely Captain John Massie’s Fluvanna Artillery and Captain John Carpenter’s Allegheny Artillery, which went into action north and south of the pike, respectively. By late morning, the Confederates had 12 guns in action against the Federal force at the junction. Before the day was over, they would have three dozen guns engaged.

“We could not see their guns, as they were masked behind some bushes, and for every shot fired, we received two in return; we were having it hot and heavy … while the other guns were waiting for further developments,” wrote Union artilleryman Frederick Wild, who was detailed to Alexander’s guns on the bluffs protecting Ricketts’s right. “Fortunately for us the enemy were not good marksmen, and their shells went screeching far over our heads, doing more damage to troops that were maneuvering in our rear, than to us right in front.”

Wallace had sent a small force to the junction on the west bank at 7 am to guard the approaches to the wooden bridge and the iron bridge. The force was composed of 200 men in five companies of Captain Charles Brown’s 1st Maryland Potomac Home Brigade and 75 men led by Lieutenant George Davis, drawn from the 10th Vermont of Truex’s brigade. The troops fanned out about 350 yards from the railroad bridge, taking cover behind the railroad embankment, which served as a ready made breastwork. Some of the men took up positions inside the west blockhouse.

In the event that the Confederates were able to force a crossing at the junction, McClennan’s brigade was deployed in two lines of battle directly behind the bridges. His three Ohio regiments formed the first line, and the 9th New York Heavy Artillery (Heavies) and the 138th Pennsylvania formed the second line.

The Heavies were one of a number of artillery units from the forts surrounding Washington that had been converted to infantry to compensate for a shortage of riflemen in Meade’s Army of the Potomac. Truex’s brigade was assembled at Gambrill’s Mill north of the railroad awaiting further orders.

About 9 am, Johnston’s Tarheels attacked the Union bridgehead protecting the junction. Mistaking the Confederates for Union troops falling back, Brown ordered his men to hold their fire. As a result, the North Carolinians killed some of the Marylanders. Brown then decided to turn over command to the more experienced Davis.

Fearing that the force on the opposite bank might be quickly overwhelmed, Ricketts ordered Colonel William Seward Jr., commanding the Heavies, to send two companies across the river to reinforce Davis. A short time later, a company from the 106th New York also went across the river. Davis ordered these three companies, which totaled about 225 soldiers, to extend his left so that it was anchored on the river and would be difficult to outflank.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Stephen Ramseur believed that a full-scale attack against the fortified Federal bridgehead at the junction would result in heavy casualties. For this reason, the North Carolina-born general and division commander instructed Johnston not to launch a major assault, but simply to maintain pressure on Davis’s force. Johnston sent sharpshooters to the Best Farm, located south of Georgetown Pike, and they clambered up into the loft of the large barn on the property and proceeded to pick off a few Federals on the left of Davis’s line.

When Union infantry detected puffs of smoke coming from the top of the barn on the Best Farm to the east, they requested that Alexander’s gunners shell the barn to drive away the sharpshooters. It did not take long for the Yankee gunners to produce positive results. “The second shot burst inside of the barn, and did the third, and the fourth, and the barn was soon on fire, and we had the satisfaction of seeing some of them being carried away on a litter, and put into an ambulance,” wrote artilleryman Wild.

At 10 am, Brig. Gen. John McCausland led his four regiments of Virginia cavalry from the Buckeystown Pike along a farm path on the west side of the Monocacy River to the Worthington-McKinney Ford located about a half mile downstream from the wooden bridge. Early had ordered McCausland to find a way to cross the river and drive off the Federal forces on the east bank defending the two bridges near the junction. Only Company B of the 8th Illinois Cavalry, which had about 40 men, guarded the Worthington-McKinney Ford. Clendenin’s other four companies had ridden farther downstream to burn any bridges they found to deny their use to Early’s troops. Heavily outnumbered, the horsemen of Company B had no other choice than to fall back and relinquish control of the ford to the Virginia cavalry.

Once across the river, McCausland ordered his 1,000 cavalrymen to dismount and prepare to advance on foot toward the Federal position. Early, who observed with his binoculars the advance of McCausland’s brigade, was elated. “McCausland’s movement, which was brilliantly executed, solved the problem [of how to cross the river] for me,” wrote Early.

Both Wallace and Ricketts observed McCausland’s advance, and Ricketts ordered Truex to shift four of the five regiments of his 1st Brigade to the Thomas Farm, which was situated north of the Worthington Farm, to oppose the attack. The Federals moved at the double-quick onto the Thomas Farm and established a line of battle facing west behind a fence facing a cornfield. Truex’s left flank rested on the Thomas farmhouse, known as Araby, and his right rested on the river. From right (closest to the river) to left the regiments in the front line were the 151st New York, 106th New York, 14th New Jersey, and 87th Pennsylvania. The 10th Vermont remained in reserve.

Ricketts also established a second line behind them that consisted of two companies from the 122nd Ohio and four companies from the 138th Pennsylvania, which belonged to McClennan’s 2nd Brigade. Wallace would eventually redeploy the remaining guns of the Baltimore Artillery to support Truex as the fighting grew in intensity on the Federal left.

While McCausland was making preparations for his attack, a Tarheel regiment attempted to get around Davis’s right flank at the Federal bridgehead at the junction. Colonel Charles Blacknall’s 23rd North Carolina attempted to sneak along the river bank and make a dash to capture the west end of the railroad bridge. But Davis had posted pickets near the river bank who warned him that a flank attack was imminent. Davis reinforced his right, and the attack was repulsed.

McCausland’s Virginians advanced in two lines at noon. They marched east from the Worthington House across cornfields heading in the general direction of Gambrill’s Mill. After advancing about 400 yards, the first line of dismounted cavalrymen charged in a ragged line toward the Thomas Farm. The Rebels “raised their battle cry, which, sounding across the field and the intervening distance, rose to me on the heights, sharper, shriller, and more like the composite yelping of wolves than I had ever heard,” wrote Wallace.

When the Confederates came to within 125 yards of the fence, the Federals who had been crouching down rose up and skillfully delivered a volley that shattered McCausland’s front line. McCausland had failed to send skirmishers forward, and this allowed Truex’s veterans to ambush the dismounted cavalrymen. McCausland’s men had expected to chase off green troops, but instead they encountered savvy veterans. Truex’s troops rested their barrels on the fence and fired at will. But McCausland’s men were demoralized. Many of the Confederate cavalry officers on horseback had been killed or wounded in the first few volleys. The Confederates who survived the wall of fire crawled back toward the Worthington House to regroup.

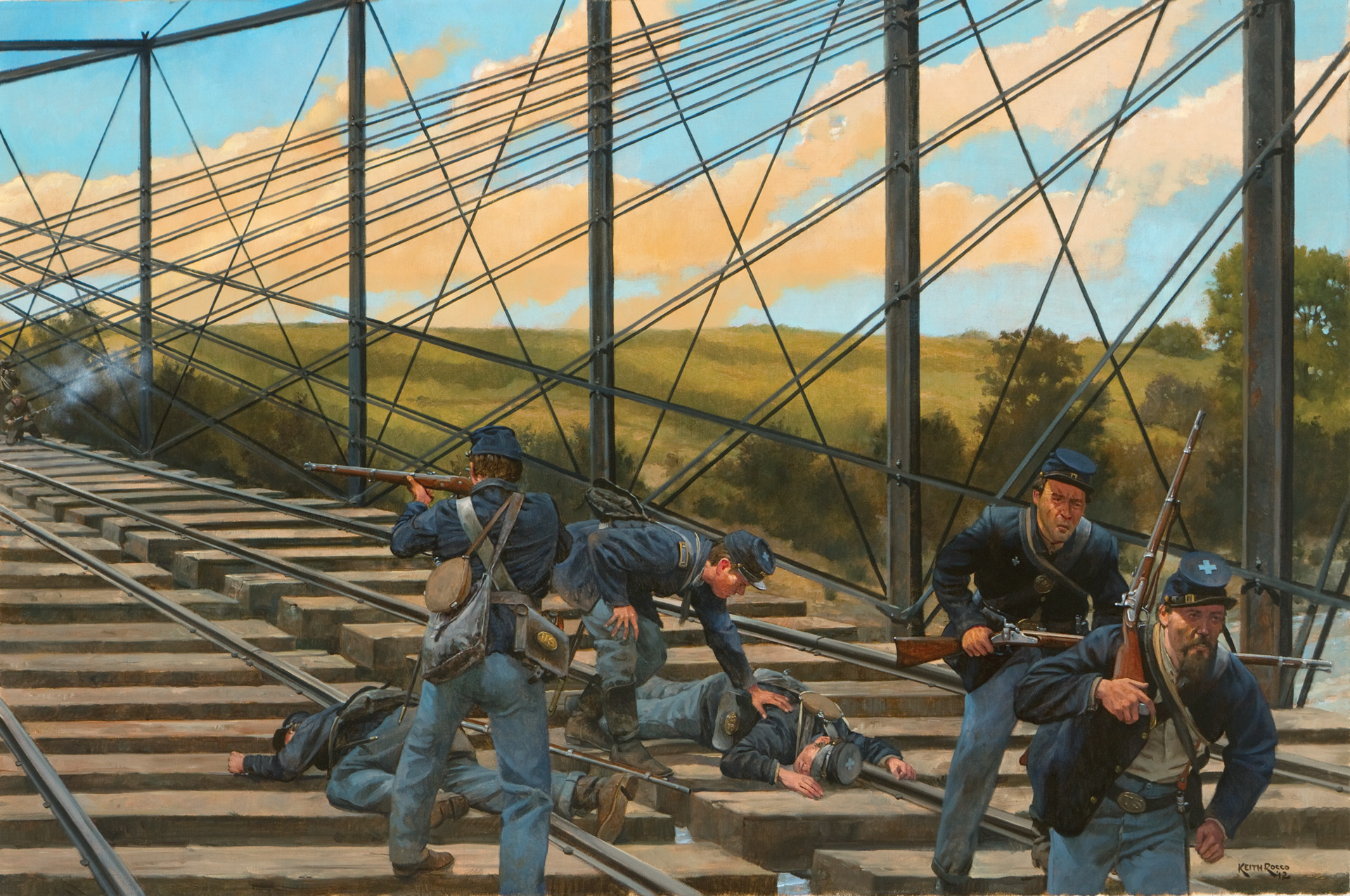

Wallace knew that the Confederates would attack again. What is more, he was facing an attack from two directions. Fearing that the strong Confederate force might scatter Davis’s troops and capture the wooden covered bridge intact, Wallace sent orders to Seward to burn the bridge. A three-man detail drawn from the Heavies inside the bridgehead gathered sheaves of dry wheat and at 12:30 pm placed them on the southeast corner of the structure. The fire “wrapped the roof in flames like magic,” wrote Private Alfred Roe of the Heavies, who observed the fire from the east bank. Seward’s orders included instructions for the three companies of New York troops to withdraw to the east bank, but Davis received no similar orders from Wallace, and so he remained at the junction.

Early had observed the repulse, and he ordered Breckinridge, whose two divisions were just south of Frederick on the Buckeystown Road, to order Gordon to reinforce McCausland. Gordon’s troops began moving toward the Worthingon-McKinney Ford about 2 pm. To support the attack, three Confederate batteries moved closer to the river on the Best Farm. Breckinridge ordered Major William McLaughlin’s Monroe Artillery and Captain William Lowry’s Wise Legion Artillery to follow Gordon across the river to support his attack. But due to the difficulty of getting McLaughlin’s battery across the rocky ford, Breckinridge’s staff decided that Lowry’s Battery should join the other batteries on the Best Farm, all of which were in a superb position to bombard the right side of Truex’s line.

McCausland wanted to mount a second attack, but it took considerable time to rally his brigade and also to carefully reconnoiter the enemy position to obtain better results. The Missouri-born cavalry general decided to shift his attack south so that he would strike the left flank of Truex’s line. While he was reorganizing his troops for the fresh attack, Gordon was making his own reconnaissance of the terrain and enemy positions.

McCausland’s dismounted cavalrymen attacked again at 2 pm. The Virginians “advanced on us in two lines of battle, mostly on our left flank, at least a half mile away, without a tree or obstruction of any kind to hide them,” wrote Corporal Roderick Clark of the 14th New Jersey. “It was certainly a grand sight as they advanced, in good order, with their numerous battle-flags waving in the breeze. We began firing at once, but it made no difference. On they came with quick step until they got within 300 yards of us.”

Wallace was watching the Confederates closely and quickly discerned McCausland’s intent. He sent orders to Truex’s regiments to move at the double quick to their left to check the Confederate charge. As the musketry grew to a roar, Wallace ordered McClennan to move the remainder of his brigade to fill the gap between Truex’s line, which had shifted several hundred yards south, and the river. McClennan’s regiments were from right (closest to the river) to left the 110th Ohio, New York Heavies, 138th Pennsylvania, 122nd Ohio, and 126th Ohio.

The fighting between the Virginians and Truex’s 1st Brigade raged on both sides of Araby and around the house itself. At one point McCausland’s boys captured Araby, but Wallace ordered Ricketts to counterattack. Wallace sent Colonel William Henry’s 10th Vermont at the double quick to take up a position on the extreme left of Truex’s line. McCausland rallied his men for another attack at 3 pm, but by then nearly all of Ricketts’s troops were engaged. The time had come for McCausland to allow Gordon’s better-led infantry to go forward.

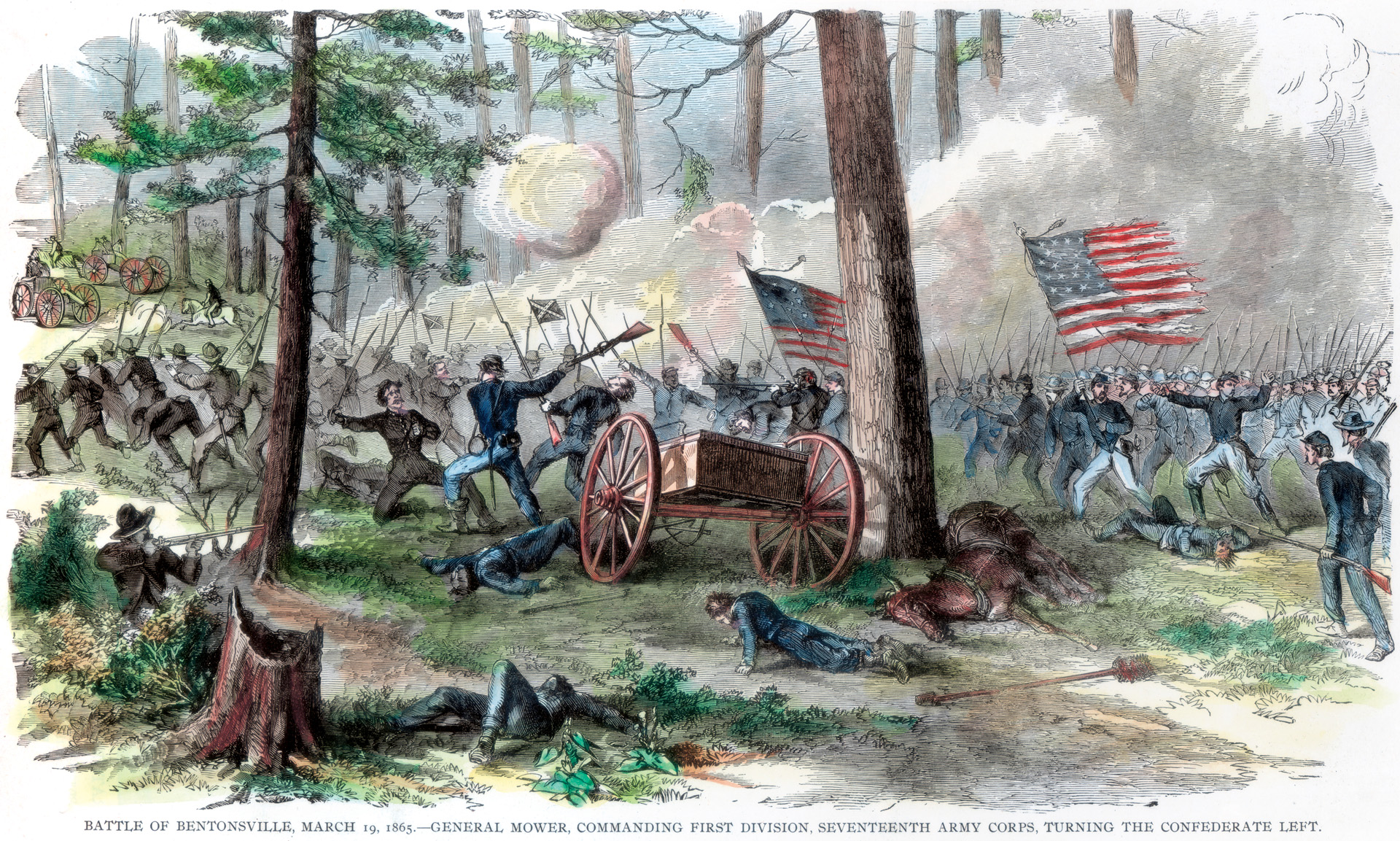

It took about an hour for Gordon’s three brigades to cross the river at the Worthington-McKinney Ford and form up for the attack. At 3:15 pm, Gordon’s infantry advanced. Because some of his regiments did not reach the battlefield in time to participate in the battle, Ricketts’s division was similar in size to Gordon’s division. The three Rebel brigades formed up in area that was for the most part shielded from Federal observations by Brooks Hill directly south of the Worthington farmhouse. Evans’s brigade advanced first on the right. It marched over Brooks Hill and emerged from the woods about 700 yards from Truex’s division on the Thomas Farm.

Gordon had noted that Evans’s troops would encounter a number of challenges in their advance. They would have to cross a small stream at the base of Brooks Hill. Then they would have to get over several fences and maintain their cohesion as they advanced through a 40-acre wheatfield with numerous shocks of wheat waiting to be collected by the farmhands. The Southern regiments would have to maintain their alignment throughout the advance despite the obstacles.

As they advanced, McLaughlin’s battery near the Worthington farmhouse opened up on the Federals. In response, Alexander’s guns hurled shells at Evans’s exposed Georgians. Truex’s Yankees had taken up an excellent position in a sunken road on the Thomas Farm that served as a natural trench perpendicular to the river. The Yankees had a clear field of fire 400 yards in front of them.

Truex’s men hoped to give Gordon’s men the same hot reception that they had given the Virginia cavalrymen. “They moved with great precision down the slope [of Brooks Hill] while the boys of the 87th and the other veterans under Truex eagerly watched their movements,” wrote Lt. Col Alonzo Stahle, who led the 87th Pennsylvania.

Regimental commanders on Truex’s left told their boys to hold their fire until the Rebels reached a large oak about 100 yards from the sunken road. “On came the rebels in two lines of battle, their field officers riding in the front of their lines,” wrote Captain Peter Robertson of the 106th New York. The Georgians charged, screaming their banshee-like Rebel yell. The Yankee line erupted in a blaze of fire that ripped into the front line of Evans’s Georgia brigade and felled many valiant Rebels. Evans was seriously wounded when a round went clear through his body, but he would eventually recover from the wound. Colonel Edmund Atkinson of the 26th Georgia assumed command of the brigade as Evans was taken to the rear.

“Wallace’s men were well posted in a road that was washed out and graded till it was as fine a breast works as I ever saw,” wrote Private G.W. Nichols of the 61st Georgia, whose regiment was in the middle of the battle line. The Federal fire was delivered with such precision and force that Georgians could not get any closer than 30 yards to the sunken road. And that was not the worst of what Evans’s boys experienced. Rather than outflanking Truex, Evans was outflanked instead. The 10th Vermont, together with the 8th Illinois Cavalry, suddenly appeared on Evans’s right flank and poured a destructive enfilading fire into the Georgians. Evans’s attack faltered momentarily as York’s Louisianans crashed into Truex’s right.

York’s Louisianans struck the 151st and 106th New York Regiments, as well as the left regiments of McClennan’s brigade. Because of the rolling nature of the landscape across which York was advancing, his men were not exposed to Federal fire until they were right on top of Truex’s Empire Staters. The New Yorkers tried to make a stand halfway down the slope that ran east from Araby to Georgetown Pike, but the pressure from York’s veteran troops was too much, and they were not able to rally until they reached Georgetown Pike.

The pike was a strong position, though, because it also was sunken from heavy traffic over the years. With the two New York regiments in retreat, the 10th Vermont, 14th New Jersey, and 87th Pennsylvania all fell back, too. Regiments of both Evans and York attacked Truex’s new position at 4 pm with great difficulty and were repulsed. “We could not see a Yankees on our part of the line during the whole advance,” wrote Private Nichols. “All that we could shoot at was the smoke of their guns, they were so well posted.”

The left regiments of York’s brigade took heavy casualties from McClennan’s men, who stood their ground and enfiladed their ranks as they rushed north toward Georgetown Pike. McClennan’s regimental and line officers had some of the men change front and pour a withering fire into the left flank of the Louisianans. The situation would not be remedied until Terry’s Consolidated Virginia Brigade struck McClennan’s line.

Terry’s veterans were anxious to get their licks in on the Yankees. The Virginians moved at the double quick through a cornfield near the river toward McClennan’s line. “On going into the fight, we went on a run, left wheel by regiment,” wrote George Pile of the 37th Virginia. In the blistering heat of the late afternoon, Terry rode alongside his men. The Virginia Military Institute graduate told them to slow down and conserve their energy.

Yankee skirmishers were waiting for the Confederates behind a fence, and they delivered a powerful volley that felled a number of Virginians. Unlike the dismounted cavalry, the veteran Rebels stood their ground and returned fire. The Yankee skirmishers fell back to join the main line. At that point, Terry’s men saw a column of Yankees moving west at the double quick toward the river. One of the Virginians shouted, “At ‘em boys!” wrote First Sergeant John Worsham of the 21st Virginia Infantry. Gordon, who was nearby, said, “Keep quiet. We will have our time presently.” Gordon ordered several Butternuts to dismantle a section of the abandoned fence so that those behind them could pass through it without having to expose themselves to fire by climbing over it. The Virginians did as told, and Terry’s troops surged into the pasture north of Araby.

Waiting for Terry’s Virginians were the 110th Ohio and the Heavies. The two sides traded volleys. After a short time, McClellan ordered the two regiments to fall back. As they did so, the Buckeyes inadvertently left a gap of about 100 yards between themselves and the river.

Terry ordered Colonel John Funk to take his regiment, which comprised the remnants of the famous Stonewall Brigade, and move along the river bank to strike McClennan’s right flank. The crack troops fell on McClellan’s flank with zeal, delivering rapid volleys that stung the Yankees. Coupled with the Confederate batteries firing into their ranks from the other side of the river, McClennan’s brigade was on the verge of being routed.

The 110th Ohio, which was posted on the right of McClellan’s brigade, suffered the most from the flank attack. The Buckeyes came “under a murderous fire of musketry and artillery, the latter coming obliquely from the front and rear and directly from the right,” wrote Lt. Col. Otto Brinkely, the commander of the 110th Ohio. With both of his flanks receiving enfilading fire, McClennan had no choice but to order a retreat to Georgetown Pike.

About the time that Gordon’s division was forming up for its attack mid-afternoon, Ramseur ordered Johnston to launch another attack on Davis’s bridgehead. The Tarheels struck at 3 pm, and heavy firing lasted for nearly an hour. Tyler, who was concerned about similar Rebel demonstrations against the Stone Bridge to the north, sent orders to Brown to withdraw his troops across the railroad bridge and then march immediately to the Stone Bridge. Davis’s men covered their withdrawal. The retreat was difficult because the rairoad bridge had been constructed without a floor; it consisted of nothing more than ties and rails laid across an iron trestle. Nevertheless, Brown’s men made it across and marched north to the Stone Bridge.

About 4:30 pm, Davis’s men began their own retreat across the railroad bridge. Davis was one of the last to step onto the railroad bridge just as Confederates swarmed the west end of it. The victorious Rebels grabbed several Yankees before they could get away and took them prisoner. Davis narrowly escaped capture. For his superb leadership that day, Davis would receive the Medal of Honor. Following on Davis’s heels, the Tarheels of Colonel Thomas Toon’s 20th North Carolina were the first Confederates to cross the railroad bridge. They immediately occupied empty rifle pits that offered a point of attack against Ricketts’s right flank.

At that point, Wallace ordered a general retreat because of a lack of ammunition. The troops were instructed to retreat to Monrovia. The following day, Wallace’s army entrained for Baltimore. The garrison and whatever reinforcements had arrived in Washington by steamer or rail would be sufficient to cover the federal capital, reasoned Wallace.

Ricketts’ two brigades had great difficulty disengaging, and McClennan’s brigade became disorganized. But Early was not interested in pursuing Wallace; he just wanted an open road to Washington. By 5 pm, the fighting sputtered out on the southern end of the battlefield.

Colonel Allison Brown had established a bridgehead manned by about 660 men on the west end of the Stone Bridge that morning. Throughout the day he had resisted half-hearted attacks by Rodes’s division. Fearing that the Confederates might seize the bridge and cut off his retreat, Wallace sent orders to Brown at 4 pm that he was to hold the bridge “to the last extremity.” At 6 pm, Rodes launched a strong attack that forced Brown to withdraw to the east bank. Many of Brown’s militia threw down their rifles and fled through the countryside. To his credit, Brown managed to lead 300 of the bravest Ohioans in an orderly retreat east along the National Pike.

Wallace’s hastily assembled Union army lost 700 killed and wounded and 600 captured. Early’s Confederates suffered 900 casualties, of which nearly 700 were from Gordon’s division.

Wanting to avoid excessive casualties, Early was reluctant to commit his forces in frontal attacks against the two bridgeheads. Thus, a battle that might have been over by noon lasted a full day. Wallace had bought precious time for Halleck to strengthen the defenses at Washington, and he had done it without having to sacrifice his entire army. Wallace lost tactically, but won strategically. As a result, his reputation was restored.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments