By John E. Spindler

On the evening of October 29, 1952, a group of French combat engineers worked feverishly to repair a ferry ramp on the Red River across from the village of Trung Ha in French Indochina. The men had news that a pontoon ferry carrying the first tank for the newly-created bridgehead was on its way. These initial troops felt relieved that armored support had arrived as the American-supplied M24 Chaffee landed and drove past them.

In a conflict that had started in 1946, these soldiers represented the spearhead for Gen. Raoul Salan, the overall Commander of French forces in Indochina, in his latest military campaign against the Viet Minh. As more men arrived, the bridgehead expanded and engineers began constructing a pontoon bridge to allow quicker movement of armor across the river. Further northeast along the waterway at Viet Tri, another group of engineers did the same. At both sites, it was a race against darkness for funneling as many men and vehicles as possible over the Red River.

General Vo Nguyen Giap, overall commander of Viet Minh armed forces, had inflicted significant reverses upon French forces over the past couple of weeks during a major campaign in the nearby Ta’i Highlands. Knowing immediate action was required, Salan stripped the Red River Delta of men and equipment, gathering the largest French military force in the history of the French-Indochina War, even larger than the one that would later fight at Dien Bien Phu. The operation would use his Mobile Groups (Groupes Mobiles), armor, airborne, and naval forces (Dinassaut) for use on the rivers in a multi-faceted plan to attack Giap’s supply route, compelling the Viet Minh commander to redirect his forces from the Ta’i Highlands into a major confrontation on French terms.

Those soldiers remaining to safeguard the pontoon bridges watched as French, Algerians, Indochinese and Foreign Legionnaires crossed and worked together to consolidate the bridgeheads. “Operation Lorraine” was a bold plan if not a major gamble, driving through jungle that forced the European power to operate along roads, while the Viet Minh, not confined to the roads, could ambush at any time, at any place.

The current fighting between French and Viet Minh was the latest bloodshed between the two combatants. In the 19th Century, France had gradually taken over this part of Southeast Asia. Starting with Saigon in 1859 and the rest of Cochinchina by 1867, French troops methodically added the rest of the region to its colonial empire: Cambodia, Annam, Tonkin, and finally, Laos. The newly-created French Indochina Union provided a wealth of raw materials—rubber, rice, tea, coal—for France and her empire.

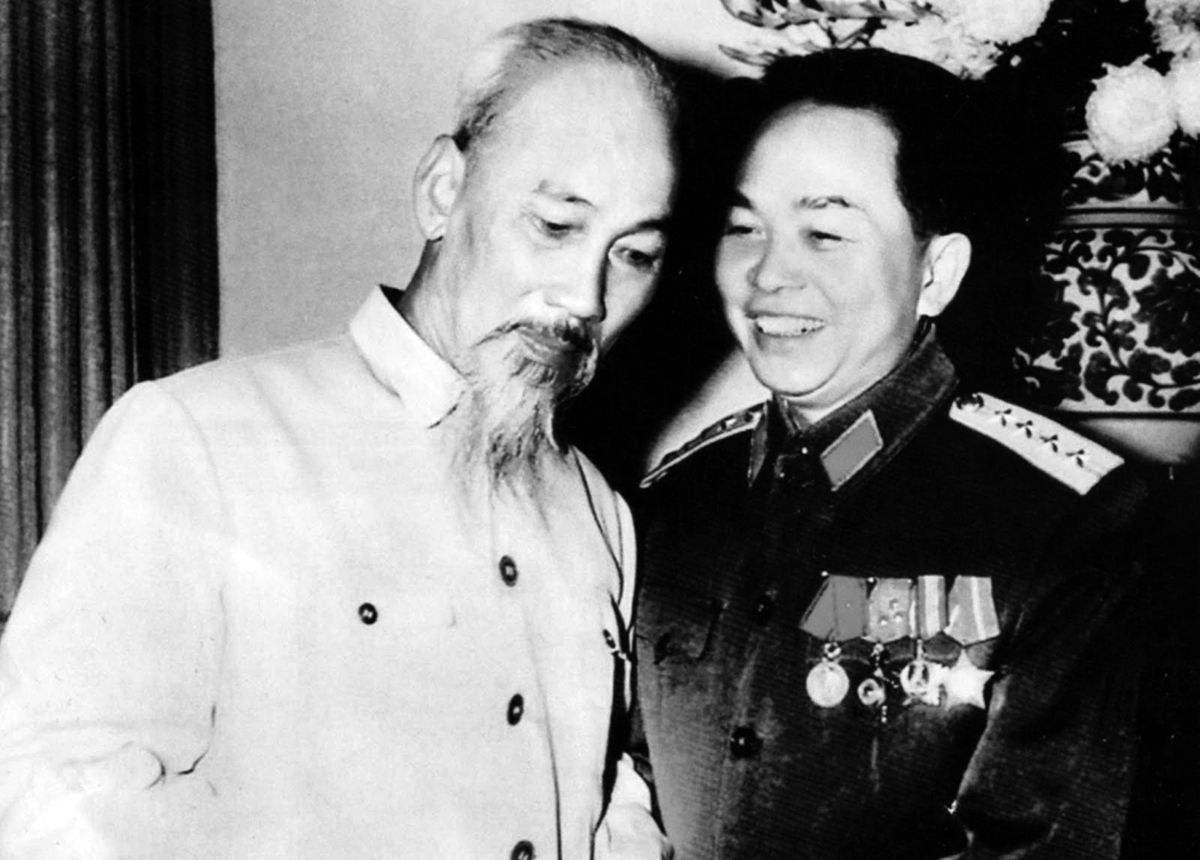

The seeds for the conflict following World War II had been planted in 1919 at the Versailles peace negotiations. It was there that the man who would become known as “Ho Chi Minh” failed in an attempt to discuss independence for Vietnam. Within a couple of years, Ho Chi Minh was heavily involved in the Communist movement. After Germany invaded France in1940, the puppet Vichy regime agreed to the occupation of its Southeast Asian colonies by Imperial Japan. Shortly after the Japanese arrived, Ho escaped to China where he chanced to meet another supporter of Communism–Vo Nguyen Giap. They developed a relationship that would shape the future of Southeast Asia. During the war, both returned to Vietnam to build and run an underground movement in opposition to the Japanese occupiers. While Ho and Giap were developing their nationalistic/communist views, a decorated World War I French officer named Raoul Salan spent a number of service tours in Northern Vietnam and Laos, becoming very familiar with the region. During World War II, Lieutenant-Colonel Salan served under esteemed General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny from the invasion of Southern France to the final push through Germany in 1945.

Japan’s capitulation at the end of World War II brought hope of an independent Vietnamese nation. Ho Chi Minh sent his troops to Hanoi, setting up a government. Unknown to them, the leaders of the three world powers had agreed France would resume control of her colonial empire, including the French Indochina Union. For the purposes of disarming the Japanese and maintaining order, an agreement was reached in which the British occupied the southern half of Vietnam and the Chinese held the north until France could dispatch its own troops.

In 1946, Ho Chi Minh worked out an agreement with France that the northern state of Tonkin would be an autonomous state in the French Indochina Union with the French retaining control of foreign policy. Both sides competed to control the population centers from cities to villages, which only escalated tensions. In December, war erupted after a surprise attack by Giap in Hanoi and his subsequent call for the people to rise up against the French. In response, Paris created the French Far-Eastern Expeditionary Corps (Corps Expeditionnaire Francais d’Extreme-Orient). Due to the limited road network, the French developed the rapid response tactic of employing paratroopers and riverine forces. In the 1947 Operation Lea, paratroopers dropped near the city of Bac Kan, almost capturing both Ho and Giap.

For the next few years, the limited number of available forces resulted in a struggle in which neither side could gain total victory. Underestimating the genius of Giap and the capabilities of the Viet Minh soldiers, the French were shocked after a series of defeats in 1950, such as Dong Khe and Cao Bang. Giap developed and executed a strategy of eliminating isolated French outposts, particularly those on the border with the People’s Republic of China. Any relief force and the retreating forces were ambushed as a result of being roadbound. The losses seriously demoralized French soldiers and exposed the ineffectiveness of its leadership.

In response, France asked Marshal de Lattre de Tassigny if he would go to Indochina. After extracting promises that he had total control, he traveled to Hanoi. General Salan, who had been in Tonkin since 1947, was named de Lattre’s deputy. Meanwhile, Giap became overconfident, launching three different attacks on the French in the Red River Delta between mid-March to the end of May 1951. At Vinh Yen, Mao Khe and along the Day River, de Lattre employed the combined might of artillery, armor and air support to his benefit. Finally engaging the enemy in set-piece battles with a technological advantage, the French exacted a heavy toll on the Viet Minh and their morale received a much-needed boost. After that first victory at Vinh Yen, the Marshal set up the “De Lattre Line,” a defensive zone enclosing the Red River Delta, including the cities of Hanoi and Haiphong. This series of 1,200 blockhouses was designed to keep the Viet Minh out of this critical region. He expanded the reliance upon Groupes Mobiles (GM) as a rapid response force. Three infantry battalions, three artillery batteries, an armored platoon and a platoon of auxiliaries went into the composition of a GM, numbering between 3,000 to 3,500 men. De Lattre was diagnosed with cancer and left for Paris at the end of 1951. After his death in January 1952, Salan succeeded him as overall commander.

Throughout 1952, Salan continued the policy of fortified bases and mobile operations. He cleared out any remaining opposition in the Red River Delta during the monsoon season. Whether it was Salan’s idea or a result from the collective brainstorming of ideas of how to increase French presence in key locations, the concept of the base aero-terrestre (air-land base) was conceived. These fortified bases possessed sufficient firepower and would be supplied via air, an idea that appealed to the French High Command. A major obstacle that constantly hampered French tactics was the insufficient quantity of military aircraft.

While Salan spent time clearing the Delta, Giap strengthened his military forces. With the border with China unguarded, he now received equipment and supplies from China. In July 1952, the Viet Minh and Beijing worked out the final details of a trade agreement. Giap’s soldiers received weapons in exchange for a partial payment made in the form of timber, rice, and opium. Additional Chinese advisors were sent, bringing the total to around 12,000. Specialized manpower support in the form of medics, radio operators, construction workers and truck drivers also arrived from China. The force that the Chinese helped was one of a 200,000-man regular army and a militia force two million strong. Giap had organized the regular force into five divisions, a number of independent brigades, and smaller support elements such as artillery.

As the monsoon season came to an end Giap put into motion a campaign in the Ta’i Highlands to eliminate the French outposts. Following up, this force would drive to the Black River and eradicate French bases, such as Na San and Son La. This new offensive was quite possibly based on recommendations from the Chinese Military Advisory Group. By focusing on these isolated strongpoints along the Nghia Lo Ridge, both the Chinese advisors and Giap knew the enemy would have difficulty bringing their superior firepower into play. If Salan countered, he would have to confront the issue of supplying a large enough relief force. Also, to find the manpower to build such an army, the French would be required to draw it from Red River Delta units.

Although Giap had hoped to begin in mid-September of 1952, his latest campaign to liberate his country was delayed until October 11. Three divisions crossed the Red River abreast, about 30 miles northwest of the De Lattre Line, along a 40-mile front this force was centered by the 308th Division, also known as the “Iron Division,” with its target the base at Nghia Lo. To the east, on its left flank, the 316th Division would pass through Yen Bai and strike towards Van Yen on the Black River. On the “Iron Division’s” right flank, Giap deployed his 312th Division. It was to capture the small enemy position at Gia Hoi. Farthest west, the 149th Independent Regiment had the task of advancing on Than Uyen and if possible, proceed to a village called Dien Bien Phu. Fighting broke out on October 15 when the 312th Division surrounded and assaulted Gia Hoi.

Salan responded by having the 6th Colonial Parachute Battalion (6ème Régiment de Parachutistes Coloniaux – 6 BPC) drop into the nearby village of Tu Le the next day. Led by the experienced Col. Marcel Bigeard, the paratroopers arrived to reinforce Tu Le and protect the withdrawal of outpost troops. Perhaps the news of paratroopers in the area distracted the men of the 312th Division as the small garrison of Gia Hoi broke out. A brilliant strategist, Bigeard knew his battalion had the difficult task of providing rearguard duty, especially as he and his paratroopers understood their role could mean their destruction. At 5 p.m. on October 17, a heavy mortar barrage hammered the Nghia Lo defenders. Following this, the “Iron Division” attacked. The key point of the Nghia Lo Ridge defense line fell in less than an hour. French casualties numbered around 700. Departing Tu Le on October 20 before he could be completely surrounded, Bigeard’s battalion and the Gia Hoi survivors headed towards the Black River. With Viet Minh in constant contact, the 6 BPC fought a hard-pressed rearguard action. By the time they reached the “safe zone,” the battalion had incurred a 60-percent casualty rate. Viet Minh casualties are unknown but probably significant due to the aggressiveness of the French paratroopers, whom the Viet Minh soldiers detested immensely.

The French reacted to Giap’s campaign by dispatching reinforcements to their Black River locations, including the base aero-terrestre at Na San. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Salan and his staff devised Operation Lorraine. With the goal of targeting the Viet Minh supply lines, the French hoped to induce Giap to divert his army from the Ta’i Highlands to counter this threat. This grand and intricate scheme would be the largest ever implemented by the French. Fielding 30,000 men, it was broken into four stages, with the last being optional.

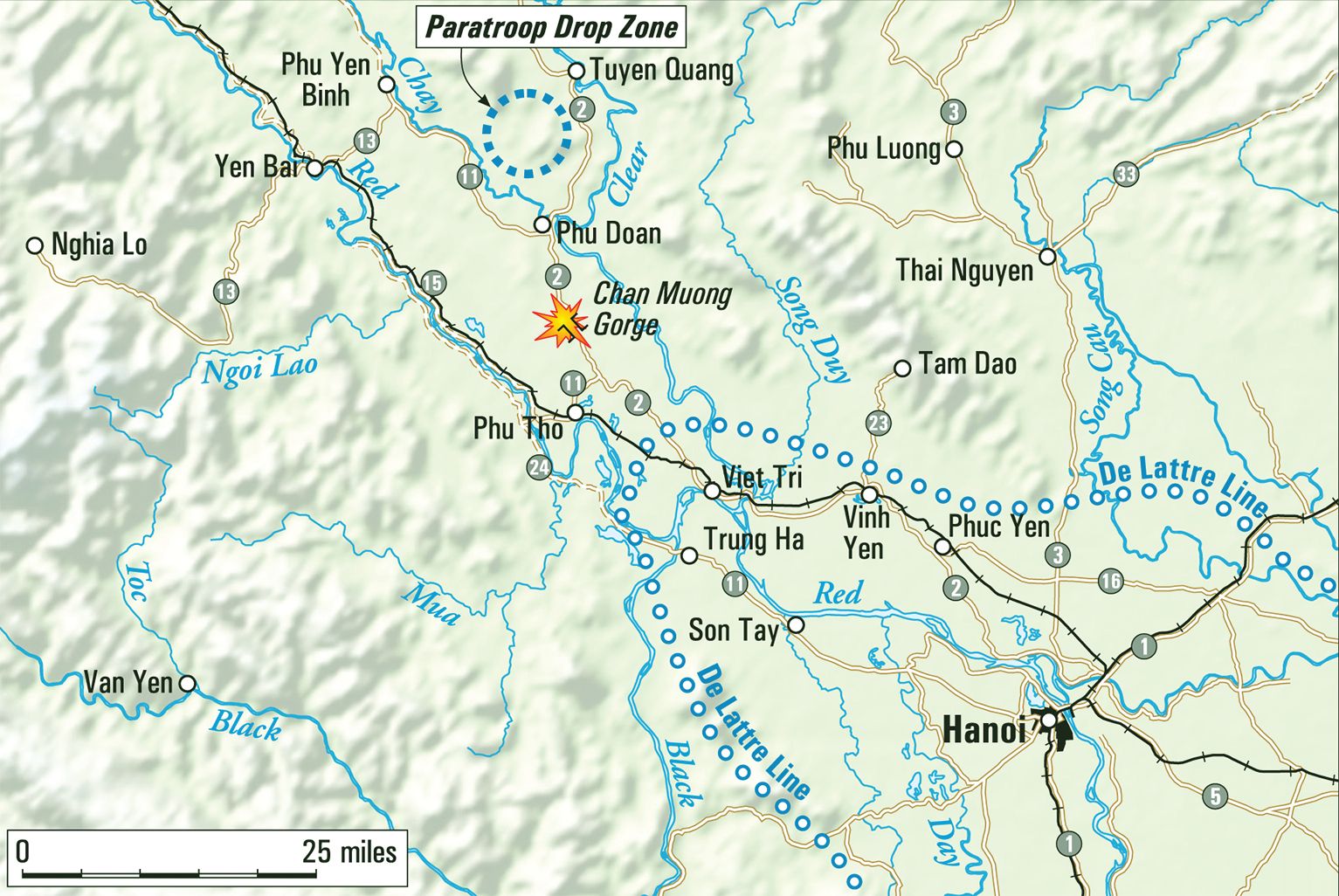

Stage I comprised establishing a pair of bridgeheads over the Red River for a thrust in the direction of the Viet Minh supply base at Tuyen Quang. Stage II projected the linking up of the two bridgeheads in a drive up Colonial Route 2 (Route Coloniale 2-RC2) to the enemy supply depot in the village of Phu Doan on the Clear River. Coordinating with the land force’s advance, an airborne force, under Operation Marion, would drop across the river from Phu Doan. These paratroopers were to be ferried into the village by a Dinassaut unit. The Dinassaut would provide support fire and prevent any enemy from escaping. Once the land forces arrived, the boats were to evacuate wounded and dead back down the river to home bases. For Stage III, the destruction or confiscation of Viet Minh weapons and equipment in Phu Doan was planned. At this point a judgment call by Salan came into play. If he opted not to order a withdrawal back to the De Lattre Line, Stage IV centered around the dangerous gamble to continue further north and target important supply bases at Tuyen Quang and Yen Bay. Every French soldier knew the risk of pressing further inland would be a lengthier withdrawal through Viet Minh-infested terrain and the almost certain odds of having to experience a large number of ambushes.

For such an undertaking, four Groupes Mobiles, including GM 1 and GM 4, furnished the bulk of the men. Among the units comprising the GMs were a battalion each from the 2nd Foreign Legion Infantry Regiment (2ème Régiment Etranger d’Infanterie -2 REI) and the 7th Algerian Rifle Regiment (7ème Régiment de Tirailleurs Algériens -7 RTA). Also included was the Indochinese March Battalion (Bataillon de Marche Indochinois – BMI), a mixture of French, Cambodians and Vietnamese soldiers. All three ranked among the best units stationed in Southeast Asia. Accompanying the GMs and providing heavy firepower were a pair of armored subgroups (Sous-Groupements Blindes) bolstered with a pair of tank destroyer squadrons as well as reconnaissance forces. Supplementing the built-in artillery of the Groupes Mobiles, a further two artillery units accompanied the strike force. A mere three engineer battalions were deployed in a massive operation that would need roads and bridges repaired.

When Operation Lorraine land forces arrived within a certain distance from Phu Doan, the airborne component of Salan’s complicated plan took off from airfields located in and around Hanoi and Haiphong. Already pulling men from positions throughout the Red River Delta, Salan had even more difficulty scrounging up the necessary aircraft for the operation. Whether the planes were American-supplied Bearcats for ground support or venerable C-47s for airborne assaults and dropping supplies to the GMs, not enough aircraft existed for sufficient support. The combat veterans of three airborne battalions would drop across the river and be met by a unit of the Naval Assault Division, Dinassaut 12 -DNA 12. Dinassaut represents an acronym for Division Navale d’Assaut, which usually consisted of a dozen or so river craft. These were American landing craft used as riverine artillery support that either had been modified with tank turrets, or carried 81mm mortars. Each Dinassaut possessed a Commandos Marine company.

To maintain the element of surprise, the initial assault boats departed from Trung Ha and Viet Tri late in the day on October 29. Crossing the Red River and expanding inland to secure bridgeheads, the French found no opposition as Stage 1 began. Spearheading the advance, the Sous-Groupements Blindes stood ready to eliminate any threat to the bridgeheads. Armed with a 75mm cannon, their M24 Chaffees outgunned anything the Viet Minh militia possessed.

Salan knew the element of surprise would not last. However, Giap already knew about the French plans. Through his network of spies, the Viet Minh mastermind had a rough estimate of the size of the land force and the routes their enemy were going to travel. Knowing how much difficulty the French would have advancing in the jungle, Giap was not overly concerned and felt the local Viet Minh was sufficient to harass and discourage the French. Being an adept military genius, he took the precaution of detaching a regiment from two of his divisions in the Ta’i Highlands—the 308th division’s 36th Regiment and the 176th Regiment from the 316th Division—and sent them south.

After a week of consolidating the bridgeheads and transporting the land component across the Red River, on November 4 both groups moved towards the appointed rendezvous near Phu Tho. A combination of inclement weather, sporadic opposition from regional Viet Minhs and damaged infrastructure hindered the desired rapid advance through the swamps and rice paddies at the outset. The next day, Colonel Bonichon led a spearhead from the Viet Tri bridgehead force with the intent to reach the village of Phu Tho. Not wanting to be caught between the two French units, the recently-arrived 176th Regiment battalions withdrew. Later that day, the two French columns met at Phu Tho. Colonel Dodelier, as the senior officer, assumed overall command. Having encountered weak resistance thus far, morale rose among the French troops.

Taking command of a task force composed of GM1 and GM4, plus the two Sous-Groupements Blindes, Dodelier led the drive towards the next goal, the Viet Minh supply base at Phu Doan (modern Doan Hung). On the morning of November 9, it was felt that the task force would reach the village that day, in time to coordinate the arrival of the airborne and riverine forces with the land element. After the Chaffees barreled through an ineffectual road block manned by elements of the 36th Regiment at the southern end of Chan Muong Gorge, the French soldiers could have not thought of this location as anything but ambush terrain as they progressed through the gorge itself.

As the task force advanced, DNA 12 made their way up the Clear River for their appointed reinforcement of the airborne assault. The 2,350 paratroopers of the 3rd Colonial Parachute Battalion (3ème Bataillon de Parachutistes Coloniaux), 1st Foreign Legion Parachute Battalion (1er Bataillon Etranger de Parachutistes), and 2nd Foreign Legion Parachute Battalion (2ème Bataillon Etranger de Parachutistes) boarded C-47s transport aircraft, both military and appropriated civilian. Arriving at the drop zone, the French observed no anti-aircraft fire targeted their aircraft. The ensuing drop seemed like nothing more than a training jump. At 3 p.m., the paratroopers controlled the area across from Phu Doan and boarded the first arriving landing craft of DNA 12. Within minutes, the first wave of paratroopers crossed the Clear River, took up key locations in Phu Doan, and awaited the arrival of the land force. Although the village residents deserted their homes upon sighting the paratrooper jump, the local Viet Minh had been taken aback at how quickly the enemy had arrived, as evidenced by what the French troops would soon uncover. At 7 p.m. the lead armored group under the command of Bonichon drove into Phu Doan as land, airborne and riverine components linked up without incident to complete Stage II.

Initial investigations verified the gathered intelligence that Phu Doan was indeed a significant Viet Minh supply center. As soldiers searched each house, the volume of discovered equipment grew. Not lulled by the relative ease of the force’s advance, an armored company drove a little further north along the Phu Doan–Yen Bay route. Their orders were to set up a defense line against a potential enemy counter-attack. While the screen force drove out, men from a tank squadron made a discovery that changed everything—four heavy-duty trucks (though some accounts list two) that did not look like the usual American-built General Motor trucks. Their markings and kilometers-per-hour speedometers revealed these trucks to be Soviet-made Molotovas. The group had revealed proof that the Soviets were supplying the Viet Minh, a startling revelation to the French High Command.

The Molotova trucks turned out to be just the start of validating Soviet-bloc military assistance to the enemy. A pair of Soviet-made 120mm heavy mortars and some rifles as well as automatic weapons added to the increasing evidence of outside assistance. In total, the French captured 1,400 rifles, 100 Thompson sub-machine guns, 22 machine guns, 30 American-made Browning Automatic Rifles, 40 light mortars, 14 medium mortars, 3 recoilless rifles, 23 bazookas, and one jeep. The search parties uncovered a significant amount of ammunition with the amount ranging from 150 to 250 tons depending on the source. Lieutenant Marion, who was in command of the force sent north for defensive purposes, discovered the Viet Minh had also hidden weapons outside of the village. In an interview with historian and author Bernard Fall, Marion said the French found 200 tons of ammunition in the Phu Doan area.

The speculation that if Phu Doan was an important, yet minor supply depot for the enemy, imagine the amount of weapons and equipment that had to be stored at the key supply centers of Yen Bay and Tuyen Quang. Of more importance at the moment would be General Salan’s decision now that Stage III had been completed. Either the strike force returns to the De Lattre Line or drives further to seize Giap’s supply centers.

Salan decided to exploit what he saw as a success so far and push further inland, thus initiating Stage IV. Part of this rests on the fact Giap had not yet redirected his divisions from their campaign in the Ta’i Highlands. There was also the underlying hope that Giap could still be pulled into a traditional set-piece battle which would allow Salan to use the French superiority in firepower to annihilate him. Leaving a detachment to safeguard Phu Doan, and most likely to deal with the confiscated materials, the main French force made their way to Phu Hien. Along the route, snipers inflicted a small number of casualties. Word of their coming had already reached Phu Hien and the advance units found it empty.

The French continued driving towards Phu Yen Binh. Patrols of armor and infantry were dispatched in the direction of Tuyen Quang to the northeast and west towards Yen Bay. On November 14, they arrived in Phu Yen Binh, 30 kilometers from Phu Doan. This would be the limit of the French advance in the operation. Troops were likely uneasy realizing they were 80 kilometers from the safety of the De Lattre Line. They knew they had to retrace their route and be subjected to ambushes.

Salan then learned the enemy had reached the Black River. The effort to divert Giap had failed. Air transport was stretched beyond capability and his forces were strung out along a very precarious path—with no chance of reaching either main Viet Minh supply center. Salan ordered the withdrawal back to the Red River Delta that afternoon, officially ending Operation Lorraine.

The same day that Salan terminated the advance, those paratroopers who had not accompanied the drive north departed from Phu Doan. The next day the French arrived back at Phu Doan and spent the next couple of days in the village. Accounts as to what the French did with the confiscated materials are difficult to find. More than likely anything the French could use, particularly American weapons and ammunition as well as the Molotova trucks, went with them and then they took measures to make sure that Phu Doan was not used as a Viet Minh supply depot again.

As the French consolidated for the drive back to the Red River Delta, the 36th Regiment prepared a major ambush site in the narrow Chan Muong Gorge. The 176th Regiment positioned itself further south. The 304th and 320th Divisions received orders to employ guerilla-style attacks along the De Lattre Line to further pressure Salan. Early on the morning of November 17th, the French left Phu Doan. Groupes Mobiles 4, under the command of Col. Louis de Kergaravat, led the column. Taking rearguard duty was Groupes Mobiles 1. As GM 4 approached the village of Chan Muong at the north end of the gorge at 7 a.m., the battalion from the 7 RTA took point and swept the village. Finding fresh holes dug in the road an hour later, the Algerians and every man along the column went on increased alert. All had the feeling they were driving into an obvious ambush, but there was no choice but to follow the road.

The Chan Muong Gorge stretched for 4 kilometers in a roughly north-south orientation that narrowed to 150m about halfway through the defile. RC 2 passed through these jungle-covered hills, hemmed in by steep cliffs at the narrowest section. In the southwestern sector of the gorge, an old Chinese fort sat atop Hill 222. The Viet Minh regimental commander set up his command post here with orders to destroy the French before they reached the village of Thai Binh at the southern end. He had his men construct a makeshift barricade across the road.

The Algerians reached the barricade at 8:20 a.m. at which time the Viet Minh opened up with small arms fire, thus starting the only major battle of Operation Lorraine. A tank platoon responded to their request for assistance. Ten minutes later and the situation had not improved. The battalion from 2 REI added their support. The addition of the Legionnaires overcame the Viet Minh ambush and the barricade was removed 30 minutes after the initial aid request, allowing GM 4 to move forward. At 9:30 a.m. de Kergaravat and the lead elements of the GM arrived at Thai Binh. The French column was strung out for 2 kilometers with the overall headquarters, reserve ammunition for the artillery, and engineering equipment having reached the midway point. Just passing into the gorge, GM 1 remained the rearguard.

The fear of ambush became reality as heavy mortars and artillery hit the Moroccan tank platoon at the head of GM 1, successfully knocking one out and blocking the road. The Viet Minh at the southern end of Chan Muong Gorge pinned down the infantry of GM4 leaving the “soft” targets, such as trucks, of the column’s center vulnerable. Along an 800-meter front, the 36th Regiment attacked. By 10:15 de Kergaravat learned how serious the situation was, fortunately both he and the GM 1 commander were outside ambush and able to direct the battle. In addition to requesting immediate close air support and ordering all artillery to commence firing on rapidly designated targets, the French colonel changed command boundaries with GM 1 now in charge of all elements north of the gorge.

For the next 90 minutes, the French were hard pressed as Viet Minh closed around the trapped vehicles of the column’s center. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting lapsed into a massacre as accounts of Viet Minh executing French wounded emerged. At noon, French aircraft arrived in support of their comrades on the ground. The Viet Minh command post and artillery on and near Hill 222 received immediate attention. These air strikes allowed the French to regroup into a better position and as they continued to hold, the battle momentum began to change. The French commanders knew two tasks had to be accomplished simultaneously: remove the vehicles blocking the road and clear the surrounding hills. On the positive side, all their units still had mutual communication. At 2 p.m. a plan was developed, though it would be an hour before French units began to disengage and organize.

The Algerian battalion spread out to cover the convoy. Infantry from the GMs attacked towards the trapped convoy. At 3:30 p.m., two companies from the BMI launched a counterattack to secure enemy positions in the hills on the eastern side of the route. The third company went to clear the road. Simultaneously, the 2 REI’s remaining 1-1/2 companies inside the gorge launched themselves aggressively towards the old Chinese fort. With less than 500 men between them, the BMI and Legionnaires violently counter-attacked, supported by artillery, armor, and heavy machine guns. Over the next hour, the attackers cleared out enemy positions. The French, Cambodians and Vietnamese of the BMI had a more difficult time than their Legionnaire brothers. The 36th Regiment outnumbered them three to one. At 4:30 p.m. a bugle cut through the din of combat. All French soldiers knew that signaled a bayonet charge. The men of the BMI struck the enemy with such ferocity that the remaining Viet Minh withdrew from Chan Muong Gorge by 5 p.m. Post-battle reports revealed all destroyed Viet Minh artillery had been eliminated through the hard work of the BMI and Legionnaires, not bombs or shells.

With infantry tired from nine hours of continuous combat, the French column reached Thai Binh at 5:15 p.m. Seventy minutes later, elements of the 36th Regiment attacked the rearguard armor with bazookas and Molotov cocktails. With artillery support, the tanks drove off the attackers, sustaining only minor damage to one vehicle. De Kergaravat made the decision that the column would halt only upon reaching Ngoc Thap. Driving in the dark, the force safely arrived at 10:30 p.m. While Viet Minh casualties can only be speculated, the Battle of Chan Muong Gorge cost the French 56 dead, 125 wounded, and 133 missing—most of these were presumed to have been executed by the enemy. Material losses amounted to six half-tracks, six other vehicles, and one tank.

By November 23, the French bridgehead had been reduced to a 5-mile-deep area at the Viet Tri crossing. Throughout the journey, the French dealt with ambushes, but nowhere on the scale experienced in the Chan Muang Gorge. At 2 a.m. the next day, elements from both Viet Minh battalions struck the French perimeter. A French strongpoint covering RC 2 was lost after two hours of intense fighting, including hand-to-hand combat. At 5 a.m. an armored counter-attack forced the Viet Minh to withdraw. At the start of December, the French took down all pontoon bridges over the Red River, only after having demolished any permanent installation in the bridgeheads and sent all heavy equipment back into the safety of the De Lattre Line.

Salan reviewed the cost of Operation Lorraine, which was higher than the returns. From the crossing on October 29 to removal of the pontoon bridges on December 1, around 1,200 dead, wounded, and missing have been calculated for the French casualties. Almost all of them in the week of November 17 to 24. No reliable Viet Minh casualty figures have been published. The failure to divert Giap from his campaign or significantly disrupt the Viet Minh supply system only added to the misery.

At the same time the French were withdrawing down Route Coloniale 2, Giap implemented his attack plan upon the French installations along the Black River. He sent his 308th Division against the base aero-terrestre at Na San. For the first time since the battles against Marshal de Lattre de Tassigny, Giap miscalculated. He believed the ease at which the Viet Minh had forced Salan to end his offensive indicated the French were tired and overextended. On this rare occasion, his intelligence network failed him. The French had twice as many defenders and more firepower than believed. In addition, Salan had the isolated base supplied via the air. The French dealt Giap a heavy loss at Na San. The victory drastically influenced the French High Command into believing bases aero-terrestres could be used to extend their influence in isolated areas.

The 30,000 soldiers taking part in Salan’s grand operation did occupy the Viet Minh supply base at Phu Doan and seized a significant number of weapons. However, those initial troops who crossed the Red River had no idea that their future accomplishments at Phu Doan would be insignificant in relation to the casualties incurred, especially at the Chan Muong Gorge battle. Plus, Giap never deviated from his campaign. For the costs in terms of men and material in relation to damage inflicted upon their enemy, Operation Lorraine can be listed as a failure.

Operation Lorraine and the subsequent Giap defeat at Na San influenced French strategy in Indochina. The success of defeating Giap at the Na San base aero-terrestre convinced the French they would be able to maintain air-supplied bases. This belief would lead to the establishment in November 1953 of the base aero-terrestre at Dien Bien Phu. Six months later and after eight weeks of intense fighting, the French surrendered to Giap and paved the way for eventual American involvement in Vietnam.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments