By Wil Deac

In March and early April 1942, American and British codebreakers uncovered indications of a Japanese offensive being prepared in the Pacific against Australia. Confirmation came with an April 9 radio intercept. Japanese strike and occupation forces intended to move south, their target designated RZP. Earlier intelligence had told the Allies that RZP stood for Port Moresby, an Australian-American stronghold on the southeast coast of New Guinea, just across the Coral Sea from Australia.

What Japanese military leaders called Operation MO was conceived as part of a two-part plan to cap their crippling attack on Pearl Harbor and successful assaults on the Philippines, Malaya, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies. Now, Operation MO would capture Port Moresby and nearby islands to sever the supply routes connecting the United States and

Australia, thereby neutralizing the latter in preparation for future conquests. Once that was completed in May, an offensive would be launched to the north against the Midway and Aleutian Islands to lure what was left of America’s Pacific Fleet, principally the aircraft carriers, into a trap. The superior Japanese Navy then would have control of the entire ocean. Vice Adm. Shigeyoshi Inouye, in overall command of Operation MO, had earlier overseen the wresting of the islands of Guam and Wake from the Americans. He expected another victory; however, he faced other unseen obstacles besides the Allied codebreakers. His own intelligence was faulty, indicating that the Americans could commit only one carrier to defend the Coral Sea. Further, Japanese planning was characteristically complex and called for the division of both forces and objectives.

MO’s key elements, aside from the invasion and close-support units, were a covering group under Rear Adm. Aritomo Goto and a striking force led by Vice Adm. Takeo Takagi. The first, assigned to protect the Port Moresby invasion force, included the light aircraft carrier Shoho, four cruisers, and a destroyer. Launched as an oiler and completed as a submarine tender, Shoho had been converted into a 30-plane carrier in January 1942. Takagi’s force boasted the large carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, along with two heavy cruisers and six destroyers. These sister carriers, larger and better armored than Japanese flattops before them, had been completed only the year before. They each could carry 72 aircraft. Both had participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

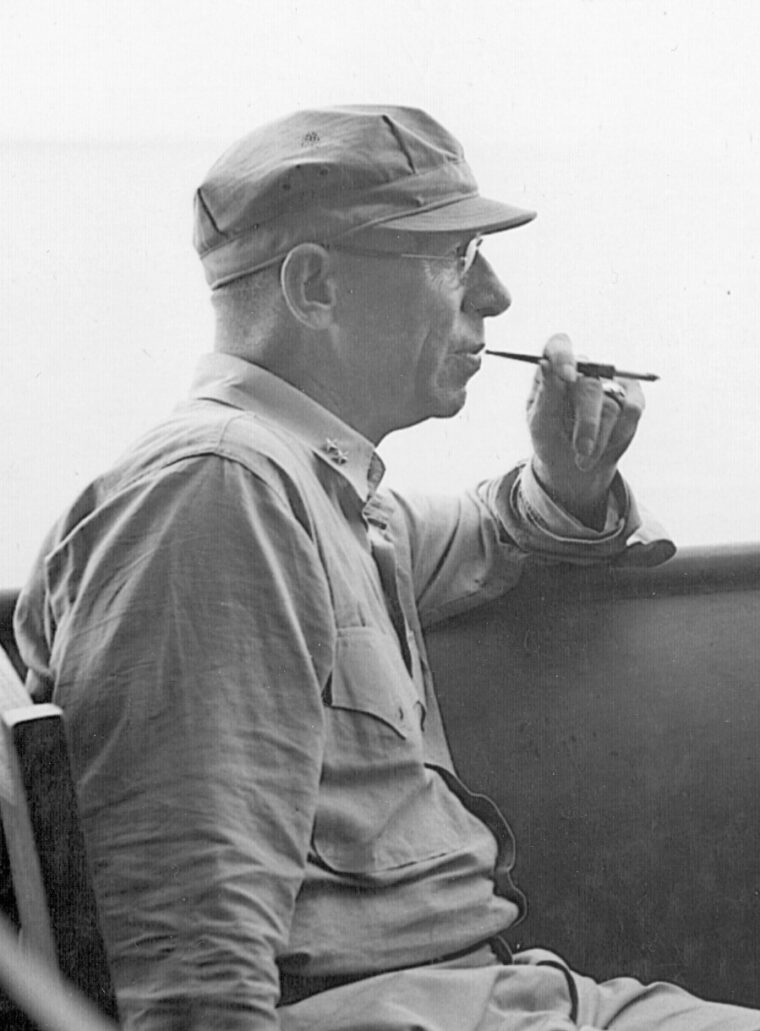

On the Allied side, Texas-born U.S. Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester Nimitz chose to meet the enemy threat by concentrating his available resources in the eastern Coral Sea. His surface force consisted of the carriers Yorktown and Lexington, seven heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, and 15 destroyers formed into three small task forces. The Yorktown force was commanded by peppery, leather-faced Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher. Rear Adm. Aubrey Fitch, a 1906 Naval Academy classmate of Fletcher’s, was in charge of the Lexington force. A support group of American and Australian warships came under Australia-born British Rear Adm. John Crace. Yorktown, completed in 1936 with an 802-foot-long flight deck, accommodated 72 aircraft. “Lady Lex,” as Lexington was affectionately called, had been completed in 1927, had an 888-foot flight deck, and carried 71 planes.

At 6:15 am on May 1, 1942, the U.S. carrier task forces rendezvoused at quaintly named Point Buttercup (16 degrees S, 161 degrees 45´ E, on nautical charts). A few days later, Crace’s flotilla joined what was to become Task Force 17 under Fletcher’s overall command. Descended from a long line of naval officers, Fletcher was no newcomer to combat. He earned the Medal of Honor during action at Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914 and commanded a destroyer in World War I. One of the first things the admiral did was order his warships refueled. The Yorktown group was topped off by the oiler Neosho, a survivor of the December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor disaster. Fitch’s force, which had dashed down from Hawaii, turned to the tanker Tippecanoe for replenishment.

On May 2, a Yorktown scout plane reported, “Japanese submarine on the surface dead ahead of task force.” Three other patrolling aircraft converged on the scene to seed the water with bombs. The sub escaped to report the presence of the Americans. Then word reached Fletcher of “enemy vessels to the northwest.” The Lexington force was still refueling when Fletcher steamed off with his group to intercept the approaching Japanese. It created a potentially dangerous situation because the U.S. carrier forces soon were about 100 miles apart and, since they were observing radio silence, ignorant of each other’s precise location. At 7 pm on May 3, Fletcher learned of the Japanese landing on Tulagi, a small undefended island north of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Island group across the Coral Sea from New Guinea.

Instead of returning to link up with the Lexington force at Point Buttercup as prearranged, Fletcher sent Neosho and the destroyer Russell to the rendezvous point with orders for all his warships to meet some 300 miles south of Guadalcanal at daybreak on May 5. Yorktown then plowed ahead to launch an early-morning strike on May 4 by Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bombers and Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers. The generally poor flying weather was ideal for the attack on Tulagi. A 100-mile-wide cold front had moved up from Australia and extended its cloud cover to within 24 miles of the target, which was under sunny skies.

As Yorktown’s 39 aircraft winged northward, Admirals Fitch and Crace were about to start out to close the 250 miles separating them from Fletcher. Meanwhile, Takagi’s striking force was churning southeastward on the Pacific, or opposite, side of the Solomons. Goto was following a more southerly course to cut through the island chain to the west of Takagi. They hoped to catch any interfering Allied ships between them.

Yorktown’s first wave of planes pounced on Tulagi at 8:15 am. Two additional waves hit facilities on the island, while four Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters made strafing runs on a newly established seaplane anchorage. A destroyer, three minesweepers, and several small craft were destroyed at the cost of three aircraft. Still out of reach of the enemy carriers, the Yorktown force turned south. The Allied warships rendezvoused on the morning of May 5 beneath a thick cloud cover that cleared later in the day. Before it did, a Yorktown Wildcat laid claim to being the first plane to be directed against an adversary by radar alone when it intercepted and downed a four-engine seaplane. Reports of the enemy fleet units heading his way, punctuated by an air raid on Port Morseby, continued to reach Fletcher.

On May 6, the day the Philippines surrendered to the Japanese invaders, the three Allied naval groups, now officially merged into Task Force 17, were once more busy refueling. Had Fletcher’s air patrol perimeter extended just a few miles farther north, his scout planes might have spotted Takagi’s striking force proceeding to curve westward around the Solomons. The Japanese were just as unlucky. Not only were their flattops not flying patrols that morning, but the sighting of Task Force 17 by an island-based seaplane did not reach Takagi until the day after the Allied warships left their vulnerable fueling stations and turned northwestward.

Ironically, the opposing fleets once came to within 70 miles of each other without knowing it, despite the fact that U.S. aircraft during the afternoon overflew the cloud-cloaked enemy carriers. By sundown, with Goto aboard Shoho covering its left flank, the Japanese invasion force began its run-in toward Port Moresby. Takagi, flying his flag aboard the heavy cruiser Myoko, was to the east temporarily reversing his southward heading to refuel his ships.

At 6 am on Thursday, May 7, Takagi broke off refueling, turned back south, and launched a reconnaissance patrol. It was an unfortunate decision, Carrier Division 5 chief Rear Adm. Chuichi Hara later said. “At 0736 one of the [patrol] aircraft reported sighting an aircraft carrier and a cruiser.” This was bad news for the Japanese, for in reality the sighted vessels were the nearly empty oiler Neosho and the escorting destroyer Sims, which Fletcher had the day before sent south to be out of harm’s way. Hara launched a strike force of 78 planes.

They were too far to be recalled when, at 9 o’clock, a cruiser’s floatplane reported “one American carrier and 10 other vessels 260 miles” to the northwest. Goto, meanwhile, received more accurate information than his superior. At 8:20 am, one of his scout planes reported TF 17’s location. The Japanese admiral, luckily for his adversary, had his hands tied by both an air strength too small for offensive action and his mission to protect the Port Morseby invasion units only 30 miles away. All he could do was prepare to repel the expected American attack.

Fletcher, in another of the many debatable decisions made by both sides, once more split his forces. He dispatched Crace’s group—the Australian cruisers Australia and Hobart, the U.S. cruiser Chicago, and three American destroyers—northwest to deal with the Port Morseby invasion group. There they would be without air cover, while TF 17 would lose Crace’s considerable antiaircraft firepower. The Yorktown and Lexington elements then swung north to challenge the enemy carriers. At 8:15 am, a Yorktown reconnaissance plane flashed a message to Fletcher’s flagship less than 300 miles to the southeast—“Two carriers and four heavy cruisers….” Aircraft were still lumbering off Lexington’s narrow flight deck in response to the sighting when, at 9:45, hundreds of miles to the southeast, planes from Shokaku and Zuikaku pounced on Neosho and Sims.

The first wave of 15 Japanese high-level bombers failed to score any hits on the two weaving ships. A second wave fared no better. The third wave came at noon. Three sections of Aichi D3A Val dive-bombers swooped down astern of the single-stack, three-year-old Sims as the destroyer steamed behind and to the left of the oiler. Three 550-pound bombs, two of which exploded in the engine room, broke Sims’ back. The warship sank in minutes with the loss of 379 lives. Twenty bombers then turned on Neosho, nicknamed the “Fat Lady.” Seven direct hits sent blazing fuel flowing on the tanker’s deck. In what may have been the first suicide attack of the Pacific War, one of the attackers smashed into Neosho’s stern. Some of the ship’s crew mistook a “prepare to abandon ship” signal for an order to go over the side and were lost. The battered Neosho drifted westward with the trade winds until May 11. Then, the oiler was scuttled after 123 men were removed by the U.S. destroyer Henley.

Neosho and Sims may well have saved TF 17. While Fletcher’s ships had been spotted, Takagi’s had not, although the Americans knew that enemy fleet units now were both behind and in front of them. Fletcher lost the opportunity to locate his opponent’s carriers when he dismissed his radio intelligence officer’s report that intercepted transmissions from Zuikaku had given away the Takagi group’s course and speed. While the Japanese were hitting the oiler and the destroyer instead of the U.S. flattops, the American planes also were following through on an erroneously reported sighting.

Short minutes after the last of 93 Dauntlesses, Devastators, and Wildcats had cleared the decks of Lexington and Yorktown, the scout plane that had radioed the 8:15 message about “two carriers” landed. The reconnaissance pilot actually had seen the two cruisers and a gunboat of an auxiliary force, not carriers. It was all a coding error by the pilot. Fletcher, reluctant to break radio silence, and hoping his planes would find a profitable target during their wild goose chase, did not recall his aerial strike force.

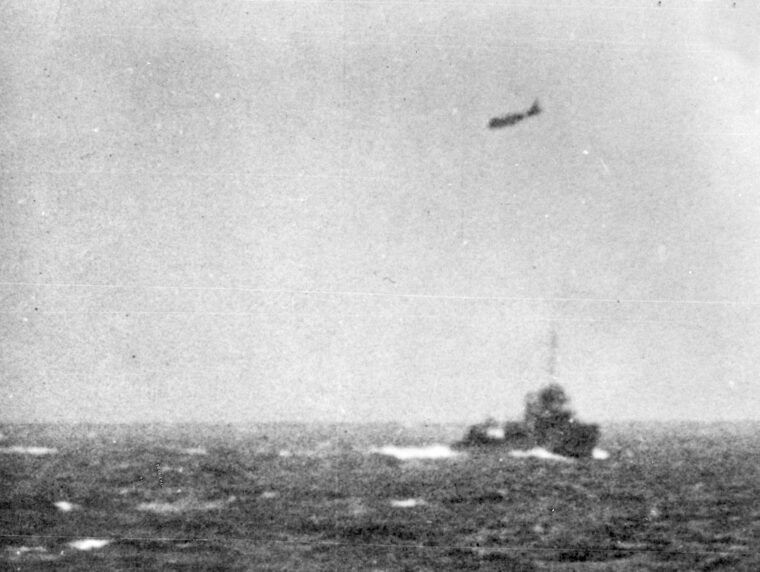

Crace’s flotilla, meanwhile, was spotted by an enemy seaplane at 8:10 am and once more luck turned a precarious situation to Fletcher’s advantage. The Japanese decided to concentrate their land-based aircraft against Crace’s six ships instead of on TF 17’s carriers. Eleven red-balled, single-engine bombers from New Britain Island jumped the Allied warships at 1:58 pm as they sailed about 150 miles from the tip of New Guinea. Crace’s vessels, moving at 25 knots in a defensive “lozenge” formation, beat off the attack. Their radar detected a second wave, this one of 12 Mitsubishi KI21 Sally bombers. The wildly maneuvering ships threw up a fence of fire that splashed five of the twin-engined bombers. The eight torpedoes they dropped were avoided.

A third wave, consisting of 19 bombers flying at 15,000 to 20,000 feet, also failed to hit its targets. A fourth assault came from Australia-based U.S. bombers that mistook Crace’s ships for Japanese. Again there were no hits. The dispatchers at Rabaul, believing Japanese pilots’ reports of major hits, canceled any further strikes they may have planned. Significantly, afraid for his transports, Inouye that morning had ordered the Morseby invasion force to temporarily retreat. Upon learning this, Crace turned his little fleet south toward Australia.

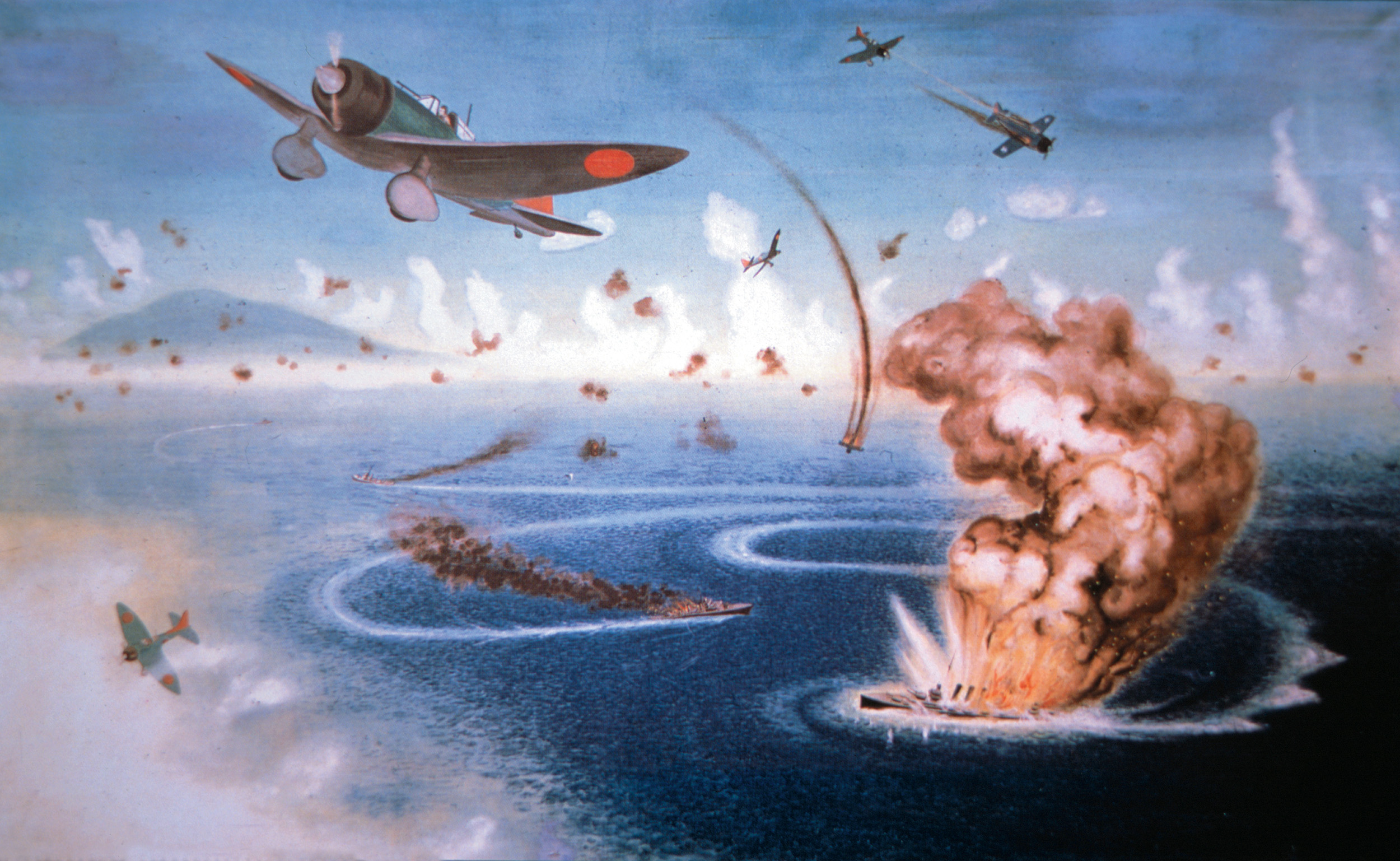

Task Force 17 had reentered the cold front and its protective cumulus cover that Thursday morning when it received two significant messages. At 10:22, land-based U.S. bombers, which proved less than successful in several efforts against the Japanese ships, reported a carrier force about 35 miles from the point where Fletcher’s aircraft were headed to hit the wrongly reported “two carriers.” Then, soon after 11 am, the U.S. aerial goose chase turned to gold. Fletcher’s fliers spotted Goto’s warships cutting the water in bright sunlight north of the cold front. It was a simple matter to redirect the American attack. With most of their planes landed for servicing after flying scouting and invasion-force cover missions, the Japanese relied chiefly on evasive tactics and antiaircraft fire to counter the onrushing American bombers.

Commander William Alt, in charge of Lexington’s strike group, nosed over his two-seat SBD at 12,000 feet in the first assault by American aviators on an enemy carrier. He was immediately followed by two others, their 1,200-horsepower engines screaming and their perforated diving brakes extended to steady and slow them. No bomb hits were scored, but five planes were blown off the stern of Shoho’s 590.5-foot flight deck by the shock waves of the exploding 500-pound bombs. Three Mitsubishi A6M Zeros tried in vain to stop the Americans. Ten more Lexington SBDs completed their runs under heavy fire. Shoho was turning into the wind to launch its refueled aircraft when Lexington’s torpedo squadron and Yorktown’s entire strike force went in between 11:17 and 11:25 am. Afire and dead in the water after 13 bomb and seven torpedo hits, the flattop sank at 11:35.

It was Japan’s first major ship loss of the war. Most of the crew and 18 of its planes went down with the carrier. Six U.S. aircraft were lost. The aircraft communications system was patched into the American ships’ public address systems so that the crews could identify with the action going on 184 miles to the northwest.

One comment stood out from the rest: Lt. Cmdr. Robert Dixon’s “Scratch one flattop!” Dixon later reached the rank of admiral. Fletcher scrubbed plans for a follow-up strike against Shoho’s support ships. The Iowa-born admiral was thinking of the still-unlocated enemy carriers and the perils of his still-green air crews returning in darkness.

Takagi, on the other hand, thought he could be less prudent. Although he lacked radar and sophisticated homing devices, his pilots were more experienced and he had a good idea of where his opponent was. He sent a dozen Val dive-bombers and 15 Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bombers against TF 17 at 4:30 pm. Handicapped by rain squalls and towering clouds, the 27 aircraft missed the Americans, jettisoned their underslung armament, and turned back. However, TF 17 radar picked them up and Wildcats flying cover were vectored onto them at 6 pm. Several Japanese bombers were downed at the cost of three F4Fs.

At 7 o’clock, three Japanese bombers finally found TF 17, but not in the way they had intended. Mistaking Yorktown for their own carrier in the darkness, the pilots blinked their lights and tried to land. The disbelieving Americans opened fire, but missed. Twenty minutes later, another enemy trio circled in a landing pattern. This time, one enemy plane fell to Yorktown’s guns. At 7:30, Lexington’s radar indicated circling aircraft less than 35 miles to the east, presumably aircraft preparing to land on the Japanese carriers. Although the latter risked turning on searchlights to guide their pilots home, 11 more bombers crashed trying to land. With the opposing forces so close, each side considered night action against the other, but for a number of reasons decided against it. Each knew, as the Americans headed southeastward and the Japanese northward during the night, that the next day would be the decisive one.

Fletcher climbed out of his bunk early on Friday, May 8, after a fitful night’s sleep. He knew that, with the enemy force about equal to his, the advantage in the forthcoming battle would go to whoever sighted the other first. The weather favored Takagi, who had been reinforced with two of Goto’s cruisers, since the cloud and rain-saturated cold front now blanketed his force. The U.S. warships were fully exposed in bright sunlight. A half-hour before sunrise, 18 reconnaissance planes lifted off Lexington’s flight deck. To the north, Japanese scout planes also were taking off in the predawn darkness.

Both sides made initial contact within minutes of each other. At 8:22 am, Flight Warrant Officer Kenzo Kanno sighted TF 17 from his single-engine Kate. Responding to his radio message, which was intercepted by Lexington, the Japanese launched 69 bombers. Kanno met the southbound aircraft and, turning about, led them to their targets. He gave his life when, fuel exhausted, his Kate went down. Less than 15 minutes after Kanno’s sighting, a Lexington scout plane spotted Takagi’s southbound carriers northeast of the American force. At 9:30, Lt. Cmdr. Dixon flew within sight of the enemy ships and corrected the coordinates of the first sighting, which were off by 45 miles. By that time, however, 48 SBDs, 21 TBDs, and 16 F4Fs were already winging northward. Hidden by altitude and scudding clouds, the Japanese planes passed high above the ocean-hugging U.S. aircraft heading in the opposite direction. Command of the air strikes had transferred from Fletcher to Fitch aboard Lexington. Fitch had years of experience in handling naval aircraft. On the opposing side, tactical command fell to Hara aboard Zuikaku.

Yorktown’s 39 SBDs climbed to 17,000 feet when they neared the Japanese fleet and circled behind cloud cover awaiting the slower torpedo planes. Shokaku, 32,105 tons fully loaded and 844.8 feet long, was launching combat air patrols at the edge of a rain squall. Her twin, Zuikaku, about 10 miles to the southwest, smoke belching from the down-turned funnels, suddenly disappeared beneath thick clouds.

At 10:57, three Yorktown TBDs roared from beneath the overcast against the only visible primary target, Shokaku. They were met by fierce antiaircraft fire and six Zeros which, in turn, were beset by Wildcats. Coordinating their attack with the torpedo bombers’ runs, the SBDs howled down to drop their projectiles. The Devastators’ white-nosed Mark 13 torpedoes, dropped at too great a distance, slow and unreliable, were easily sidestepped by Captain Takatsugu Jojima’s Shokaku.

The dive-bombers had better luck, but not much. Lieutenant John Powers dropped his bomb at so low an altitude that it assured his and his rear gunner’s deaths. But it also assured him of a hit and earned him the Medal of Honor. His 500-pounder started a fire on the carrier’s starboard bow. The wooden flight deck was damaged such that Shokaku, which had sent up another seven aircraft during the battle, could recover planes but no longer launch them. A second 500-pound bomb demolished a repair shop on the flattop’s starboard side aft.

The initial U.S. sighting error threw off the succeeding Lexington strike force. The SBDs returned home after failing to find the enemy. Six F4Fs, losing three of their number in the ensuing dogfight, drew off the Zeros to enable Lexington’s torpedo and scout planes to press their attacks.

The TBDs dropped their tin fish, but to no effect. The four SBD scout planes (Dauntlesses used for reconnaissance had longer ranges but lighter bomb loads than those assigned to dive- bomber roles) completed their dives. Shokaku incurred a third hit, again not a serious one. After the attackers left, the carrier reported 94 dead and 96 injured. Most of her aircraft were transferred to Zuikaku, which emerged from the rain squall as her sister ship’s fires were brought under control. At 1 pm, Takagi sent the damaged flattop north for repairs at Truk, 800 miles north of Rabaul.

The 69 Japanese planes—18 torpedo bombers, 33 dive-bombers, and 18 fighters— that were dispatched at about the same time as the American strike forces reached TF 17 while Shokaku was enjoying the brief lull between the attacks by Yorktown and Lexington aircraft. Fletcher, at his customary position on Yorktown’s starboard side bridge, was tensely awaiting the outcome of the American strikes.

Fitch, conducting air operations for both ships from Lexington’s bridge, had turned the carriers toward the enemy fleet to reduce the distance his returning pilots had to fly. It was 10:55 when Lexington’s CXAM-1 radar detected unidentified aircraft at a distance of about 70 miles. Fitch ordered TF 17 to turn about to the southeast at full speed and sent all flyable planes into the air. Unfortunately, nine F4Fs were on deck refueling and went up too late to reach effective intercept altitude. The eight Wildcats already on combat air patrol were low on fuel, too close to the carriers, and positioned at 10,000 feet when the enemy bombers were at 18,000 and 6,000 feet. In desperation, the available SBDs were assigned an interceptor role. Like Shoho, TF 17 was forced to rely mainly on maneuvers and antiaircraft gunners for protection.

At 11:18 am, the battle, in the words of an American sailor, “busted out.” While one group of torpedo bombers attacked Yorktown, two others concentrated on Lexington. Captain Elliott Buckmaster, skipper of the 25,500-ton Yorktown, which had half the turning radius of the older Lexington, evaded all eight torpedoes aimed at the ship’s port quarter. At 11:24, after a short breathing spell, the flattop was targeted by dive-bombers. Yorktown, churning at 30 knots, was rocked by the dozen or so bombs bursting in the sea around it as the carrier’s guns added to the din. One 550-pound bomb struck close to the island on the starboard side and sliced through the wooden deck, killing 37 men, wounding 33, and starting a fire on the fourth deck. By 12:15, flight operations unimpaired and the fire soon extinguished, Yorktown found itself just over three miles south of a very badly stricken Lexington.

At the very onset of the air assault, two groups of low-winged Kates caught Lexington in a classic “anvil” attack—three aircraft converging on each bow. Their torpedoes thumped into the lightly rippled ocean from 50 to 200 feet up and about a half-mile from their prey. No amount of maneuvering enabled Captain Frederick Sherman to avoid all the missiles. One torpedo detonated against the 43,055-ton carrier’s port side forward at 11:20. Almost simultaneously, a second tore into the hull aft of the first opposite the bridge.

Instead of focusing on the Vals that were charging down from 17,000 feet, most of the Wildcat protective screen chased after the now-harmless Kates. A small 120-pound bomb smashed into a portside ready-ammunition box, while a 550-pounder struck the elongated funnel structure behind the bridge. Near misses punched hull plates and ruptured fuel tanks. To give a final touch to the Dante-esque chaos of flame and smoke, Lexington’s siren jammed, its shriek making it seem as if the ship were screaming in pain. Fewer than 20 minutes after it started, the attack was over. The Japanese had lost 43 aircraft, the Americans 33.

Oil ballast was shifted to correct Lexington’s 7-degree list to port. The torpedo holes were plugged and the carrier’s engines remained undamaged despite the flooding of three boiler rooms. By 12:30 pm, the fires had been doused so that the ship’s air group could be recovered. Ten minutes later, the damage control officer was able to report this progress, adding a suggestion that if “you [the captain] intend to be hit by any other torpedoes it would be as well to take them on the starboard side.” Apparently satisfied with the results of the battle—each side having exaggerated the damage inflicted on the other—the opposing fleets pulled away from each other, Americans to the south, Japanese to the north.

Disaster struck TF 17 at 12:47 pm. Lexington trembled from a violent internal explosion. Highly volatile aviation fuel fumes from lines ruptured during the bombing were ignited by sparks from a carelessly untended motor generator. Several small detonations followed. As the blazing flattop maintained a 25-knot speed, its crew fought the conflagration raging inside the hull.

Despite the confusion and growing damage, Lexington continued landing its aircraft. Then, at 2:45 pm, a second major blast occurred. A thick, dark smoke cloud mushroomed into the air. Fletcher, having resumed tactical control, responded to requests for assistance from Lexington’s bridge. The destroyer Morris edged alongside the huge carrier to pass across fire hoses. Other escort vessels stood by for increasingly likely rescue operations. Nineteen aircraft still aloft were redirected to Yorktown’s flight deck.

At 4:30 in the afternoon, the stricken warship was dead in the water. About 37 minutes later, Fitch called down to Sherman from the upper bridge, “Well, Ted [Sherman’s nickname], let’s get the men off.” When the “abandon ship” order came, the crewmen, having assembled on the slightly tilting flight deck, climbed down lines or leaped into the warm water to be picked up by a cruiser and three destroyers. The evacuation was so disciplined that even the ship’s dog was saved. The last of the 2,735 officers and men to leave and be rescued was Captain Sherman. The destroyer Phelps gave the shattered flattop its coup de grâce with five torpedoes. “Lady Lex” sank slowly, taking with her over 200 men and 36 aircraft. A final explosion occurred as the carrier slipped out of sight in the darkness.

On Rabaul, Inouye believed that there were no American carriers left. Further, with Crace’s group heading away, the path was theoretically open for the invasion of Port Moresby. Yet, having lost much of his air power and still threatened by land-based aircraft, the cautious Japanese admiral ordered Takagi’s withdrawal and postponement of the Port Morseby invasion until after the upcoming Midway operation. He was overruled by Navy commander-in-chief Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto, who told Takagi and Goto to return and finish off the Allied forces. The Japanese found only empty sea before breaking off their search on May 11. The invasion of Port Moresby was ultimately canceled. It was the same day that Yorktown left its escorting cruisers, steaming to Pearl Harbor for repairs, which were made in time for the carrier to take part in the Midway action in June.

One historian has said that the Battle of the Coral Sea could more accurately be called the “Battle of Naval Errors,” given the many mistakes made by both sides. He added, however, that it was “an indispensable preliminary to the great victory of Midway.” There is little question that the Coral Sea engagement was a tactical victory for Japan. On the other hand, it was a strategic victory for the United States. Operation MO’s objective of capturing Port Moresby was not attained; it was Japan’s first naval defeat of the war.

The Japanese loss of 77 aircraft (to the American 66) and 1,074 men (about twice as many as the United States) was more than the country could afford. Two of the nation’s most lethal carriers were eliminated from the upcoming Battle of Midway, which was the turning point of the Pacific War. Shokaku took two months to repair. Zuikaku lacked aircraft and trained aircrews.

The historical significance of the Coral Sea action is twofold. It was the first naval battle fought by fleets that never actually saw each other. As the first carrier-to-carrier clash, it also marked a turning point in military history—the ascendancy of naval aviation as a decisive factor in warfare at sea. n

Wil Deac is a military history writer based in Washington, DC. He is the author of Road to the Killing Fields, the story of Cambodia’s war of 1970-1975.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments