By Wil Deac

The days following Pearl Harbor were grim ones for the United States. Headlines screamed of one Japanese victory after another. Shocked, their confidence shaken, Americans needed a solid symbol of courage to rally around—a hero. That morale-boosting need was answered on December 10, 1941, by a 26-year-old Floridian named Colin Purdie Kelly, Jr.

A Hollywood casting director could not have discovered a better subject. Colin Kelly, endowed with open, boy-next-door good looks, was born on July 11, 1915, into a wealthy Scots-Irish Protestant family that had produced a congressman, a religious leader, and a Confederate officer. Growing up in the Florida Panhandle town of Madison, where his father owned a 5,000-acre turpentine farm and cattle ranch, the wavy-haired youngster excelled in school (except for frequent tardiness) and in the Boy Scouts.

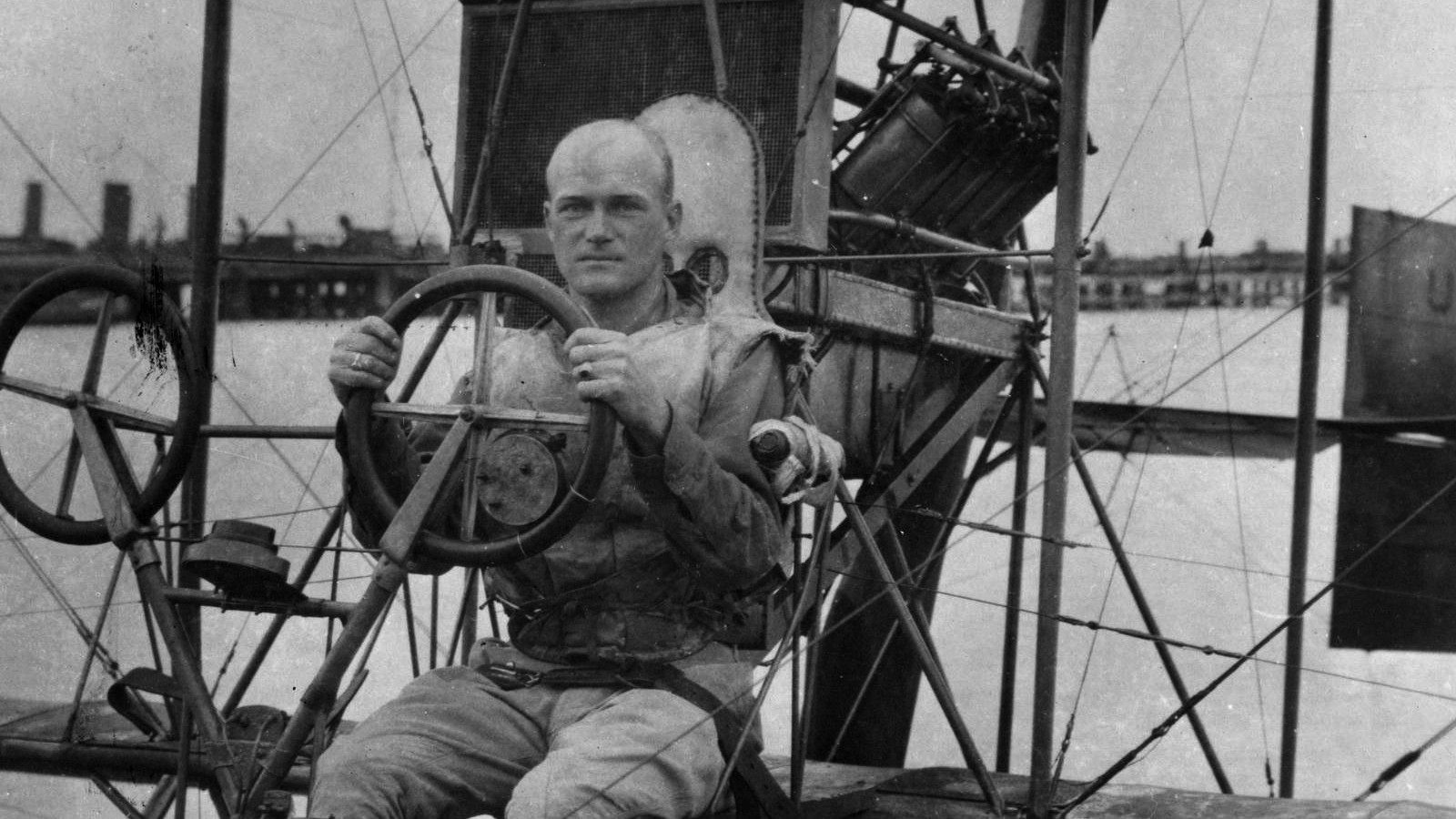

“He always talked about airplanes,” his father would recall, and the aspiring pilot made his first flight with a visiting barnstormer. Kelly won an appointment to West Point, where he was “a striver rather than a star.” There he met a New Jersey stenographer, Marion Wick, whom he wed in 1937, shortly after earning his second lieutenant’s gold bars. Their only child, Colin III, was born in May 1940. He too, would graduate from the U.S. Military Academy, subsequently becoming an army chaplain. The tall, slim Kelly, soon flying bombers for the Army Air Corps, was promoted initially to first lieutenant, then to captain.

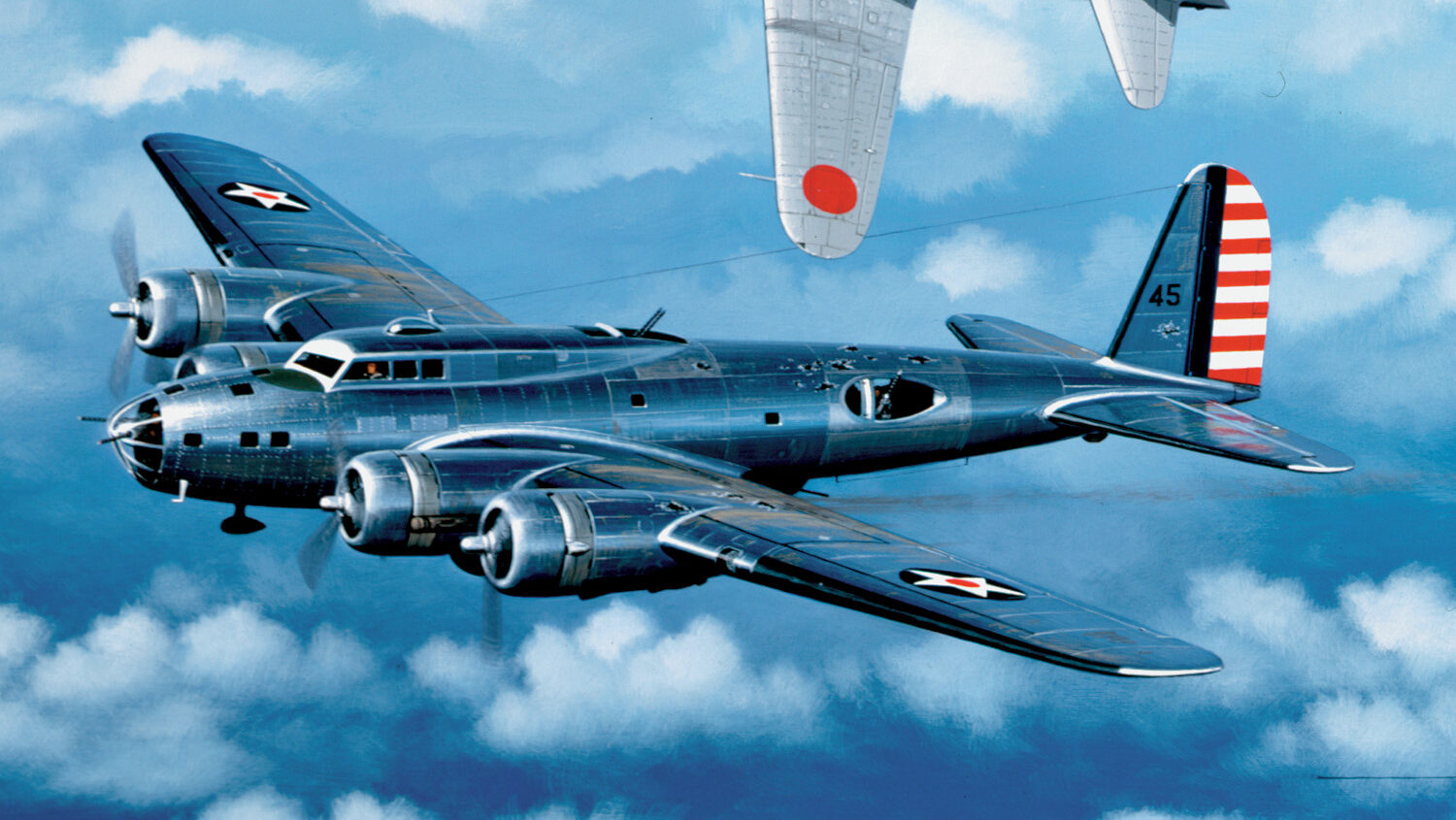

Kelly was adjutant to the 19th Bombardment Group’s 14th Squadron under Major Emmett “Rosie” O’Donnell, Jr., when orders were cut in September 1941 to ferry nine Boeing B-17C Flying Fortress heavy bombers from Hawaii to the Philippine Islands. The American-administered islands were being reinforced as diplomatic relations between the United States and Japan deteriorated. The B-17C was a far cry from the formidable fighting machine that later ranged the skies over Hitler’s Europe. It lacked tail armament, power turrets, and self-sealing fuel tanks.

War came to the Philippines about 30 minutes past noon on December 8, 1941 (December 7 east of the International Date Line). In one of the war’s most controversial episodes, General Douglas MacArthur’s air force was caught on the ground when 190 Japanese planes, delayed by a morning fog that blanketed their Formosa bases, struck the main island of Luzon just over 10 hours after the Pearl Harbor attack. Eighteen of 21 B-17s on the island, 53 of over 100 fighters, and more than two dozen other aircraft were gutted in one short hour for a loss of seven enemy fighters. Fourteen B-17s, including Kelly’s, escaped destruction because they were 600 miles to the south on Mindanao Island.

Twenty-four hours later, with three prongs of the 3rd Imperial Japanese Navy reported nearing northern Luzon, the 14th Squadron was ordered to Clark Field some 50 miles north of the capital city of Manila. Swinging into their landing patterns late on December 9 after an uneventful hop, the four-engined bombers were abruptly diverted to San Marcelino, a new emergency airstrip nearby. They were greeted with tracer rounds fired by trigger-happy Filipino recruits. Luckily, the brief gunfire caused no casualties. In succession, the eight Fortresses bumped down on the dusty grass runway and taxied past the bullfrog shapes of several Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk pursuit planes.

Wednesday, December 10, began wet and cloudy, as though even the heavens were in mourning. Kelly and the 63 other squadron airmen, forced to sleep as well as they could in their aircraft or on the ground for lack of quarters, shook the stiffness from their bodies in the predawn darkness. They had no specific mission, no idea of how the war was going. As they settled down to a modest breakfast, O’Donnell took off for Clark Field to get orders. Kelly and the others walked over to the communications shack set up in an old wrecked B-18 bomber fuselage. Drops of rain began to pelt down. O’Donnell quickly sent word—take off at dawn for Clark to load bombs.

Powerful Wright-Cyclone engines blasted into life; three-bladed propellers spun off drops of water in ghostly spirals. Thundering aloft and executing 45 degree turns one after the other, the bombers were swallowed by the thick clouds crowning the mountains to the east. Kelly, the first to reach Clark, circled his B-17 into a landing. Bomb craters, devastated buildings, and the skeletal remains of aircraft dotted the barely operable base, a primary target of the initial Japanese raids. Two other Fortresses touched down before the rest were ordered back to San Marcelino. The reason fluttered atop the control tower—a red flag warning of an impending air raid.

While the young captain was briefed on his mission by the 19th Group commander, ground crewmen began raising bombs into the belly of the olive-drab B-17. They only had time to load three, a mere 1,800 pounds of bombs in a 67.5-foot-long plane designed to carry almost 21/2 tons. The three aircraft were soon airborne.

Targeted against an aircraft carrier said to be off the Japanese landing beachhead at Aparri, Kelly and a second bomber set individual courses for the northern shore of Luzon. The third Fortress, piloted by Lieutenant G.R. Montgomery, assumed a more westerly heading toward an enemy invasion site at Vigan, which had been struck by American aircraft earlier that morning. It dropped its single 600-pounder without effect before returning safely to Clark to rearm for a second sortie.

The second B-17, flying at 25,000 feet above scattered clouds, aimed its eight bombs at transports disembarking men and supplies at virtually undefended Aparri. Challenged by Japanese Mitsubishi Zero fighters that quickly appeared on the scene, the American escaped only by diving steeply into the clouds at 350 miles an hour. Lieutenant G.E. Schaetzel landed his plane, one engine shot out and its tail shell-peppered, at San Marcelino.

Meanwhile, Kelly’s B-17 broke into clear weather just east of Vigan, 20,000 feet above the ships of the Japanese 2nd Surprise Attack Force. As yet unchallenged, the American pilot turned northeastward toward Aparri. There, Kelly’s crew counted six warships running interference for several troop transports landing 4,000 men of the Nipponese 48th Division’s 2nd Taiwan Regiment who were directed to secure landing fields. Another warship, which appeared to be a battleship of the 29,330-ton Kongo class, steamed about four miles farther out. Coordinating rudder pedal and control wheel movements, Kelly banked away from Rear Admiral Kenzaburo Hara’s lst Surprise Attack Force and pursued a northerly course over the South China Sea.

The Babuyan Islands, blurred by clouds, passed beneath the starboard wing. The pilot dropped the big Boeing to within 4,000 feet of the corrugated gray-green water. Just short of Formosa, the weather worsened into a heavy rainstorm. Rivulets of moisture buffeted the plane’s plexiglass windshield. Kelly advanced the throttle and guided the B-17 back to its original altitude. It was nearly noon when he swung the aircraft around. Scattered shipping had been sighted, but no carrier. They would attack the large warship they had spotted earlier off Aparri.

Light, ineffective antiaircraft fire met the Americans’ return. While the smaller warships (destroyers misidentified as cruisers) took evasive action, the bigger vessel disdainfully continued parallel to the coastline. Kelly eased his plane to over four miles altitude and leveled off into a bomb run 10 minutes out from his selected target. In the glass nose of the B-17, bombardier Sergeant Meyer S. Levin hunched over his gyrostabilized Norden bombsight. He took over control of the bomber from the pilot. Near him, navigator 2nd Lt. Joe M. Bean stood ready to man the .30-cal. weapon mounted in one of the six gunports in the plexiglass.

Behind them, in the cockpit, Kelly and co-pilot 2nd Lt. Donald D. Robins could see the sleek warship slide slowly beneath the nose of the Fortress. Aft of the cockpit, four gunners—Staff Sergeant James E. Halkyard, Technical Sergeant William J. Delehanty, and PFCs Robert E. Altman and Willard L. Money—manned .50-cal. machine guns in the sloping radio compartment roof, the elongated ventral “bathtub,” and the starboard and port sides of the plane’s waist. The Brooklyn-born bombardier finally depressed the release button. “Bombs away!” he called into the intercommunication system.

The B-17 bolted upward as the three 600-pound missiles howled seaward in train. Resuming control, Kelly turned the plane, bomb bay doors closing, sharply toward land. Two splashes far below were followed by what seemed to be a flash, smoke, and a water spout. To the rejoicing crewmen, the third bomb seemed to detonate directly on their target. A group of white Japanese Zeros flying at 18,000 feet spotted the water rings left by the bombs. Coincidentally, they were part of the Formosa-based flight earlier bound for the Manila area which had forced Kelly to prematurely leave Clark Field.

The Japanese quickly sighted the B-17 about 4,000 feet above them. As they full-throttled upward in pursuit, another half-dozen of the single-seat fighters, painted light green, joined them. It was the first aerial encounter between a Flying Fortress and the Japanese. The bomber’s defensive fire, as well as its speed and altitude, kept the enemy at bay long enough for Kelly to use the clouds for cover. Although the Americans thought they might have eluded their pursuers, navigator Bean kept a wary watch against overhead attack through a rounded glass dome situated just behind the cockpit. Luck ran out about 50 miles north of Clark Field, just as breaks in the clouds promised an easy landing. Bean had just lowered his head to glance at the altimeter.

With successive crashes, the observation dome shattered and the instrument panel exploded. The burst of machine-gun bullets and cannon shells that beat a deadly tattoo across the top of the Boeing bomber also virtually tore off Delehanty’s head and gave Altman a painful head wound. A pale green Zero of the 21st Air Flotilla shot by them. Two more of the green fighters, having stealthily stalked the B-17, made overhead passes. Seven of the radial-engined white fighters, the ones that had been hovering over Aparri, joined the fray. Forming a single line to compensate for the Zero’s limited high-altitude maneuverability, the 23rd Flotilla aircraft, each firing two 7.7mm nose-mounted machine guns and two 20mm cannon in the wings, swooped hawk-like on their prey.

The uneven battle moved over the extinct volcanic cone of Mount Arayat and then Clark Field. Three of the Zeros led by Navy NCO Saburo Sakai, who with 64 victories was to survive the war as Japan’s fourth-ranking ace, tagged onto the bomber’s defenseless tail. Kelly turned his plane, kicked first one rudder pedal then the other, fishtailing the B-17 to let its waist guns bear on the tenacious red-balled fighters.

Sakai, already credited with two aerial victories over China and a P-40 downed two days before, bore in from beneath and behind. He was unseen because the radio operator assigned to the belly gun position had climbed up into the fuselage earlier to handle landing instructions. The Japanese aviator subsequently recalled that, as he opened fire, “pieces of metal flew off in chunks from the bomber’s right wing, and then a thin white film sprayed back. It looked like jettisoned gasoline, but it might have been smoke. Abruptly, the film turned into a geyser.”

As Sakai turned aside, his ammunition expended, the low-pressure oxygen tanks in the B-17’s radio compartment exploded to create a fiery holocaust in the metal fuselage. A burst from another Zero probably severed the elevator cables and plunged the plane into a dive. Sakai followed the Fortress down until it disappeared into the overcast just below 7,000 feet.

“Bail out. Bail out!” Kelly called over the intercom while the bomber was still above the clouds. Smoke filled the fuselage and blazing fuel from a raptured tank gushed into the empty bomb bay. Fighting for control as the doomed plane nosed downward, the pilot gave his crew the precious minutes they needed to jump to safety. Halkyard, Money, and the bleeding Altman escaped through the rear compartment door just as the B-17 winged into the billowy murk.

Sakai witnessed their exit and saw their parachutes open. Levin and Bean, in the meantime, struggled with the lower forward hatch, pushing it partly open after removing a rusted hinge pin. They too, made it out. Co-pilot Robins was pulling himself through the top cockpit hatch when a violent explosion blew him into space. Although dazed and burned, he managed to pull his parachute ripcord. A probably inaccurate after-action report noted that some of the green Zeros made three firing passes at the Americans descending helplessly in their chutes, chipping Bean’s ankle. The report was hotly contested by Sakai after the war’s end.

The 19.5-ton falling torch that was Kelly’s B-17 was raining debris as it broke out of the clouds on an even keel. It smashed down along a dirt road in the wild country about two miles west of Mount Arayat. White parachutes, popping one after the other out of the somber overcast, brought most of the surviving crewmen to earth within a quarter of a mile of each other and about five miles north of Clark. Gathered together by Bean, they were found shortly afterward and driven to the airfield. Robins was picked up by a base ambulance. Colin Kelly’s broken body, parachute unopened, lay near the smoldering wreckage of his bomber, the first Flying Fortress lost in combat. Delehanty’s corpse had been thrown almost 50 yards farther to the north.

In death, the courageous Army Air Corps captain gave a defeat-stunned United States its first hero of the war. An official communiqué, based on inaccurate post-mission debriefings, stated that Kelly had “successfully attacked the battleship Haruna.” On the night of December 12, the well-known voice of radio commentator Lowell Thomas told Americans of “hailing the name of Colin Kelly, who sank the battleship Haruna. He plunged almost into the mouths of the blazing Japanese guns, it seemed, before he released his stack of bombs. Then Colin Kelly, plane and all, vanished in the tremendous explosion that made an end to the Japanese battleship.” Subsequent reporting gave the brave officer the Medal of Honor.

There were other acts of heroism in the Philippines that fateful December 10. For example, Lieutenant Samuel H. Merrett of the 34th Pursuit Squadron died in the explosion of a ship he was strafing with his obsolete P-35 fighter at the Vigan beachhead. These other acts got lost in the chaotic opening days of the Pacific War. Whether there was early confusion or calculated deception, some of the truth about Colin Kelly’s last flight was also lost.

Melodramatic reports of a suicide dive against or a bomb dropped down Haruna’s smokestack only detract from the story of the young officer’s true sacrifice. According to Japanese records, the ship his B-17 attacked failed to hit was the 10,000-ton heavy cruiser Ashigara, flagship of the Northern Cover Force. Haruna, one of the “most often sunk” ships of the war, was on the other side of the South China Sea supporting Japan’s Malaysian campaign.

In fact, no battleships or aircraft carriers were used in the initial phase of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines. Finally, Kelly was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, not the Medal of Honor. None of the inaccuracies, however, could dim the truth that Colin Kelly’s bravery saved most of his crewmen and gave his country a psychological boost in its gravest hour of need during World War II.

Wil Deac is a frequent contributor to WWII History and an expert on the espionage and clandestine operations that took place during the conflict. He lives in Washington, DC.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote a letter to “whoever would be President” when Colin Kelly III, the pilot’s son, was old enough to enter West Point, to grant him admission.

The son declined the endorsement, and took the examinations instead. He got in. After Army service, he became a clergyman.