By Scott A. Beal

On May 31, 1932, Franz von Papen achieved the pinnacle of a long career serving his country when, in a surprising move, the aging President Paul von Hindenburg named him Chancellor of Germany. The hand of fate had taken an unusual route in guiding this career diplomat and spy to the helm of Germany. Intent on preserving peace while contending with unstable political and economic situations domestically, Papen’s six-month administration as chancellor instead was dominated by controversy and international intrigue. Both characteristics seemed to follow Papen throughout his career, before and after his term as chancellor.

Born October 29, 1879, in Werl, Westphalia, Franz von Papen was the son of a wealthy landowner. Like many young men of the day, he decided upon a career in the military. By World War I he had risen to become the military attaché to the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. Papen had married the niece of a French marquis, who taught him to speak almost perfect French. The couple had grown quite popular among the Washington diplomatic corps by 1915 when Papen was declared persona non grata by the U.S. government and ordered home to Germany.

His unofficial job while in America had been that of spymaster. Charged with overseeing German espionage agents and their activities concentrated on preventing American armaments from reaching England, Papen was given a considerable budget to fund the operation. Dummy corporations were established which then took all the orders they could for Allied armaments. With no intention of filling the orders, their customers were continually given excuses about the endless delays, thus helping Germany’s cause.

Other fictitious firms created by Papen bought all the gunpowder available in the United States under the guise that these fabricated companies were manufacturing grenades and artillery shells destined for England. Instead, the gunpowder languished in warehouses never to see use during the war at all.

Though these two operations were relatively successful in assisting Germany’s war effort, other efforts were not, primarily because of the ineptitude of Papen’s subordinates. In particular was one Heinrich Albert, an attaché at the embassy who inadvertently left his briefcase on a train in New York. The case was promptly seized by an American intelligence agent. It contained sensitive documents, and their eventual publication in American newspapers caused significant embarrassment to the German diplomatic corps, particularly Papen.

Incidents such as this increased the tension between Franz von Rintelen and Papen as well. Sent from Berlin to coordinate sabotage efforts in the United States, Rintelen was intent on blowing up military installations and warehouses. Rintelen’s approach to espionage vastly differed from that of Papen, who preferred quieter, more sophisticated methods of harassing Germany’s enemies. Papen was of the opinion that Rintelen’s “loose cannon” approach was not only reckless in its own right, but it potentially endangered the plans implemented by Papen as well.

While Rintelen was busy funding sabotage operations against U.S. merchant vessels and the 1917 explosion at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in San Francisco (in which 16 children were killed), Papen was consistently cabling the Abwehr (Germany’s intelligence agency) insisting that his more flamboyant associate be recalled to Germany.

Papen got his way, and Rintelen was indeed ordered home to Germany. However, instead of being allowed to continue assisting the war effort by using his own methods, Papen was placed in the position made vacant by Rintelen’s departure, that of supervising sabotage in the United States. While he never ordered acts of overt terrorism in the United States like his predecessor, Papen evidently did authorize such activities in Canada.

He dispatched men to blow up crucial portions of the Canadian Pacific Railway, thus preventing troops from reaching the transports destined to take them to England. However, Canadian authorities and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police were able to thwart this mission. While he was coordinating these activities, he also supervised operations preparing forged identification papers for German citizens who were eager to return to Germany and fight for their homeland.

Papen was Charged with Tracking Down Arab Guerrillas Under the Command of T.E. Lawrence, the Now Famous “Lawrence of Arabia.”

Papen’s activities finally caught up with him and caused his ejection from America. Specifically, the attempts to sabotage American armament production and a conspiracy to blow up Canada’s Welland Canal were the ultimate causes. These events would resurface in the American press when Papen became German chancellor in 1932, and in his autobiography he attempted to clear up his part in the activities. Much of the evidence against Papen in 1915 was supplied by British agents who were not completely unwilling to manufacture information implicating a German national during wartime. It was under this cloud that Papen headed home to Germany, but he would not remain there very long.

Sent to Spain briefly in 1917, Papen was serving again as military attaché when he reportedly had contact with the ill-fated German spy, Mata Hari. In 1918, mainly because of his bungling attempts at espionage in the United States and a less than stellar performance in Spain, Papen was sent to Palestine where he was to serve as the chief of staff of the 4th Turkish Army. Leading a ring of spies for the Turks in their war against the British, he was charged with tracking down Arab guerrillas under the command of T.E. Lawrence, the now famous “Lawrence of Arabia.” Here too, he was unsuccessful. During this period he also implemented clandestine operations that encouraged rebellion in both India and Ireland, as well as more sabotage in the United States.

With the end of World War I, the devoutly Catholic Papen returned to Germany and embarked on a career in politics, joining the Catholic Centre Party. In 1921 he was elected to the Reichstag, the German parliament, settling into a position as an unexciting but wealthy member of his party, and ultimately serving as a party deputy. By 1932, the suave, well-mannered Papen had attracted the attention of party leaders. At the time, former German Chancellor Heinrich Bruning was leading the Catholic Centre Party. President Hindenburg had been nurturing Bruning as his protégé, but Bruning was dropped from this role. With Hindenburg lacking a favorite, Papen was offered up as replacement for Hindenburg’s support.

It was General Kurt von Schleicher, Hindenburg’s chief adviser, who orchestrated Papen’s ascendance to German chancellor. In late May 1932, Schleicher posed Papen to Hindenburg as a patriotic German who would answer the call of his country to serve, even at the expense of offending his own party. At the president’s insistence, Papen accepted the role reluctantly.

The government Papen presided over was a strict one and tolerant, if not favorable, to Nazi ambitions. In June 1932, he rescinded the ban on the Nazi Party’s paramilitary SA (Sturm Abteilung or Storm Section, also known as the Brownshirts) and deposed Prussia’s Social Democratic government. One positive accomplishment of his administration was that he did manage to get Germany’s war reparation debts cancelled, but it was not enough to validate his other actions. Papen’s attempts to disregard the Weimar constitution and implement his authoritarian rule had managed to alienate one of the key men who had helped place him in power, Schleicher.

General Schleicher then took matters into his own hands by convincing several cabinet ministers to flout Papen’s initiatives, and the chancellor resigned in December 1932, only to be replaced by Schleicher himself at the direction of President Hindenburg.

It was this series of events that led Papen, still stinging from his apparent betrayal by Schleicher just weeks prior, to seek out Adolf Hitler in January 1933 and forge an agreement with him. This now infamous arrangement would see the aging Hindenburg appoint Hitler as chancellor on January 30, 1933, with Papen as vice chancellor. Papen had been successful in persuading Hindenburg that he could prevent Hitler from enacting many of the extremist Nazi programs he was anxious to implement.

In this scenario, Papen envisioned his own return to power, believing that Hitler would be malleable to behind-the-scenes manipulation. Vice Chancellor Papen quickly learned that Hitler was not so easily swayed from the aims of his Nazi agenda. Although Papen was not as extreme as Hitler in pushing the persecution of German Jews, his attempts to justify that discrimination were apparent in a speech delivered in Gleiwitz in 1934. “There can certainly be no objection to keeping the unique quality of a people as clean as possible,” Papen had stated, “and to awaken the sense of a people’s community.”

Papen Narrowly Escaped Death When as Many as 400 Members of the SA Were Purged

Papen was now effectively trapped in a powerless position. As vice chancellor for almost 18 months, he was unable to sway Hitler from his extremist plan, but so desperate to hold on to any shred of power was Papen that the alternative of resignation and possessing no power at all was even worse. If in his present situation he was powerless, his proximity to Hitler meant he was relatively safe.

Papen narrowly escaped death when as many as 400 members of the SA were purged on June 29, 1934, during what came to be known as the Night of the Long Knives. Many of those murdered were high-ranking Nazis of the old guard, including the SA leader and Hitler’s longtime friend, Ernst Roehm.

Hitler’s justification for this systematic slaughter was based on claims that the SA was planning to overthrow the government. Actually, Hitler gained the tacit support of the professional German military and elevated the role of the SS, under Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, to greater prominence as a result of the purge. It was also a convenient vehicle for Hitler to rid himself of anyone he considered opposed to the Nazi regime. Counted among the victims that night was Schleicher, the most recent chancellor and Papen’s former patron turned rival. Also illustrative of how close the vice chancellor’s office was to peril that night, Papen’s press councilor was killed.

By now it had become painfully clear to Papen that he had grossly overestimated his ability to control Hitler, and he finally resigned as vice chancellor three days later. The resignation was most likely prompted by self-preservation and a keen awareness that he could just as easily have been a victim himself on that horrible night.

Two weeks previous, in a letter to Hitler on July 12, 1934, the day before the German people learned of the purge, Papen praised the Führer for his actions concerning the SA’s purge of June 29. He wrote, “Allow me to say how manly and humanly great of you I think this is. Your courageous and firm intervention have met with nothing but recognition throughout the entire world. I congratulate you for all you have given anew to the German nation by crushing the intended second revolution.”

Franz von Papen was certainly not stupid in attempting to curry Hitler’s favor, lest a fate similar to one that befell Schleicher visit itself upon him. Nor was he the type to fade into obscurity, content to have escaped death so narrowly. In the wake of the assassination of Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss, the subsequent unrest in Austria, and Mussolini’s massing Italian divisions near the Brenner Pass, Papen was abruptly summoned by Hitler and assigned the task of maintaining stability in Austro-German relations. The fact that Hitler had never publicly accepted or announced Papen’s resignation as vice chancellor weeks earlier was now the perfect opportunity to vacate the vice chancellor’s office without the appearance of internal strife.

In the last official documents signed by President Hindenburg, Papen was officially appointed ambassador to Austria on July 28, 1934, arriving in Vienna on August 15 amid an atmosphere of distrust and intrigue. He cautiously embarked on the task of calming the volatile situation, all the while intent on orchestrating Austria’s eventual annexation into Germany, with that unification being achieved by referendum on April 10, 1938.

From his post in Austria Papen once again retired, his government service apparently over. Then, in 1939 Hitler appointed Papen ambassador to Turkey, the primary task being to prevent that nation from forming a partnership with the Allies. Also among his responsibilities was overseeing the immense German spy network that existed in neutral Turkey. It was here that he came into contact with one of the best known spies of the war.

In 1943, one of Papen’s clerks at the German Embassy introduced him to an Albanian named Elyeza Bazna. As a personal valet to British Ambassador Sir Hugh Knatchbull-Hugessen in the British Embassy in Ankara, Bazna had offered to steal British secrets for the Germans. Papen jumped at the opportunity, christening Bazna with the code name Cicero.

Cicero (Bazna) began to supply Papen with voluminous amounts of information in return for large sums of currency in the form of British bank notes. The payments originated from the office of German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. Unknown to Papen, the bank notes sent as payment for Bazna were counterfeit. The information that Bazna provided was not counterfeit at all, and in fact it seemed so incredible that the Germans receiving it refused to believe its authenticity. Most notably, there were records of meetings between Churchill and Roosevelt at the Casablanca Conference, and documents containing the code name Overlord, the designation for the Allied invasion of Europe planned for 1944. The Germans were unable to discern the precise meaning of Overlord and never pursued it.

Hitler Personally Presented Papen with the Knight’s Cross of the Military Merit Order.

This flow of pilfered information continued unabated under Papen’s watch until the British were informed that their Ankara embassy had a security leak. The name Cicero had appeared in a cable from Papen to Ribbentrop, and an American agent of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in the German Foreign Ministry Office spied it on Ribbentrop’s desk. This information was then passed from the OSS agent in Berlin to OSS station supervisor Allan Dulles in Switzerland, who then told British intelligence of the leak.

The British investigated, but try as they might they were unable to identify Cicero. That is, until a secretary in the German Embassy defected to the British and told British intelligence that Cicero was the ambassador’s valet. The ambassador and investigators immediately questioned Bazna, but he refused to crack under their interrogation, denying all charges. He was dismissed and left the embassy, embarking almost immediately for South America via Lisbon, Portugal. With him went one of the best sources of information Germany had.

Papen remained on station in Turkey until he was recalled to Germany in late July 1944, less than a week after the attempt on Hitler’s life on July 20. His fate was far from certain as he returned amid the reprisals over the assassination attempt being visited upon people at every level of the German government and armed forces. Papen met with Hitler days after his arrival. After Papen briefed the Führer on the situation in Turkey, Hitler personally presented Papen with the Knight’s Cross of the Military Merit Order. This decoration was proof enough of his loyalty for those rounding up suspects in the assassination attempt. Papen was removed from any danger connected with the consequences of the failed coup. In September he once again retired to his home in Westphalia.

He would not enjoy a leisurely retirement for long. In November 1944, amid the growing threat of advancing U.S. forces, he and his family were forced to flee their home, which was subsequently looted and burned to the ground by the U.S. Army.

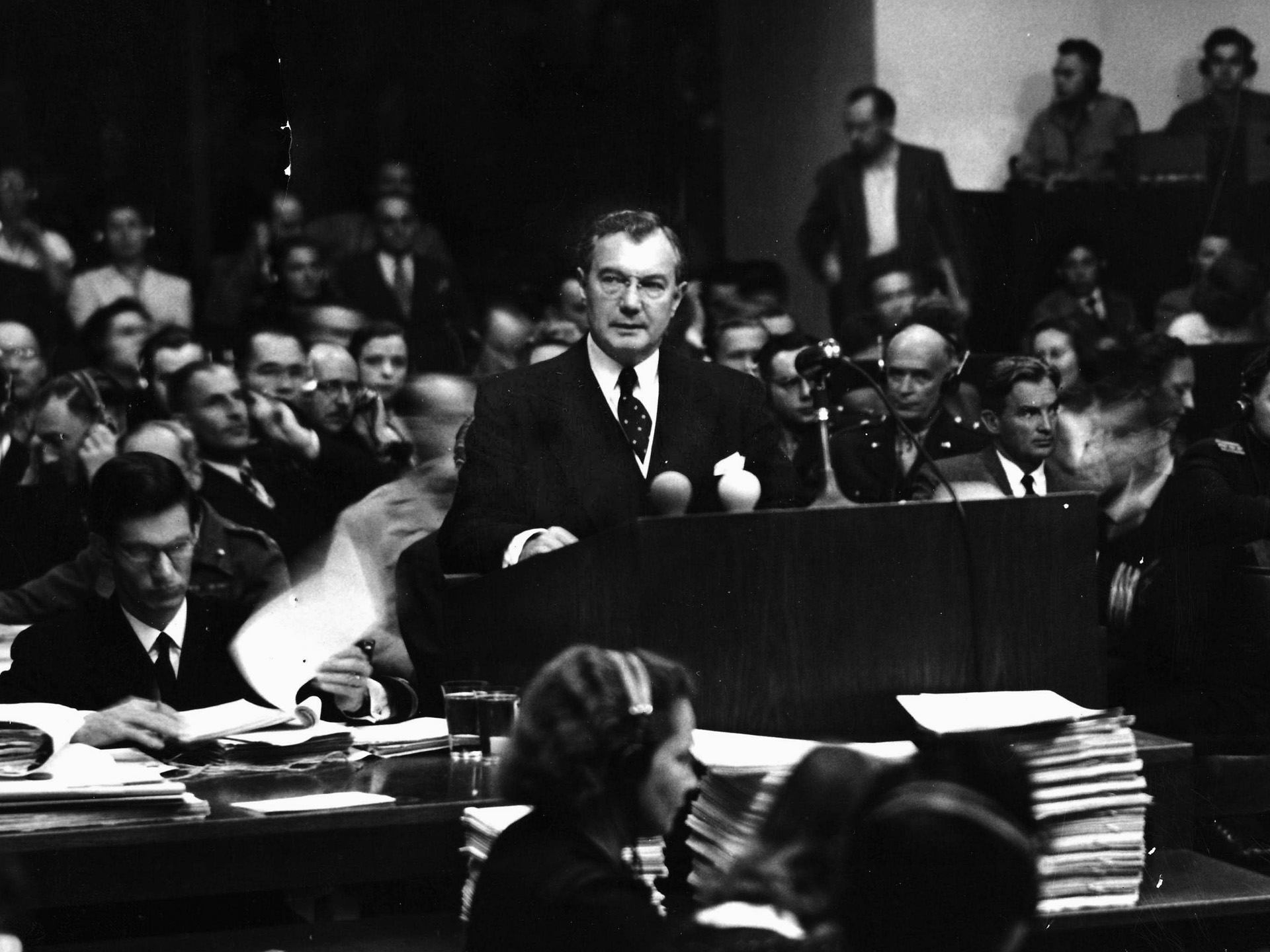

Arrested by Allied troops at the home of his daughter and son-in-law on April 10, 1945, Papen was transported to Rheims, and ultimately to Nuremberg. He was placed among the prominent Nazis on trial there. He was found not guilty of “conspiracy to prepare for an aggressive war” by the Nuremberg tribunal in 1946. However, on May 1, 1947, he was declared by a German court to be a “major offender” and sentenced to eight years in prison for being a “prominent Nazi.” He appealed this sentence and, most likely because of his wealth, was released in January 1949, but forced to pay a fine.

Although Papen lost his state pension and driver’s license, his assets and property were returned to him. Publishing his autobiography, entitled Memoirs, in 1952, he painted a portrait of himself as meaning well but caught up in historic events and unable to stop the Nazi machine once it had started. Whether he truly was a wily diplomat adept at the highest levels of Machiavellian intrigue and remaining one step ahead of his rivals, or an honest man caught up in epic events, the impact of his role in German government before and during the war remains for history to judge. Franz von Papen died in Obersasbach, Germany, on May 2, 1969.

First-time contributor Scott A. Beal is employed in the marketing field. He is an avid student of World War II and writes from his home in Mason, Illinois.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments