By Victor Kamenir

By the end of January 1945, Hitler’s desperate Ardennes Offensive had ground to a halt. Though the last-ditch push to the west had inflicted heavy casualties on American forces, it was the German army that suffered irreplaceable losses in men, equipment, and materiel and was no longer capable of offensive operations. The Allies regrouped and raced for the Rhine River, the last major natural obstacle to Germany.

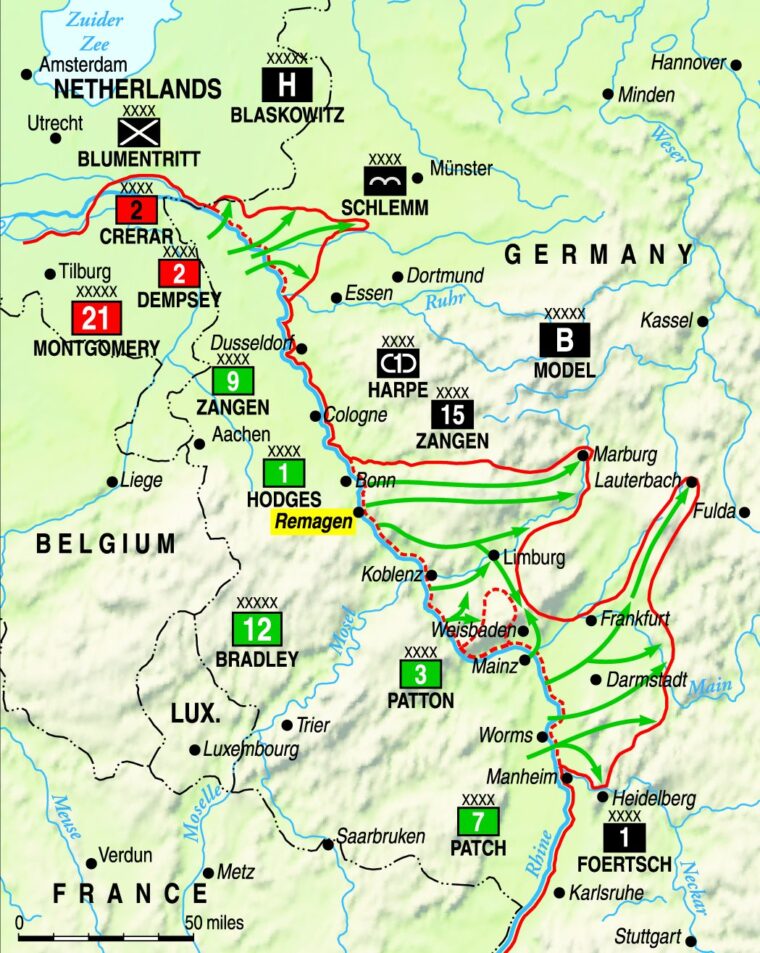

The Allied forces advanced toward the Rhine on a broad front with British General Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in the north and U.S. General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group in the south. Bradley’s army group was composed of the U.S. First Army under Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges on the left and the U.S. Third Army under Lt. Gen. George Patton on the right. Supreme Allied Commander in Europe General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the senior Allied command expected to find no bridges over the Rhine still standing.

First Army considered two possible river crossing sites on the extremes of its flanks—one in the sector between Cologne and Bonn in the north, and at Koblenz in the south. In both cases, the American forces would have to fight on the river’s east bank through heavily-wooded terrain with a poor road network to reach the Ruhr-Frankfurt autobahn. In the central sector near Remagen, where steep cliffs overlook the river, the terrain was deemed too prohibitive to be considered a viable crossing option.

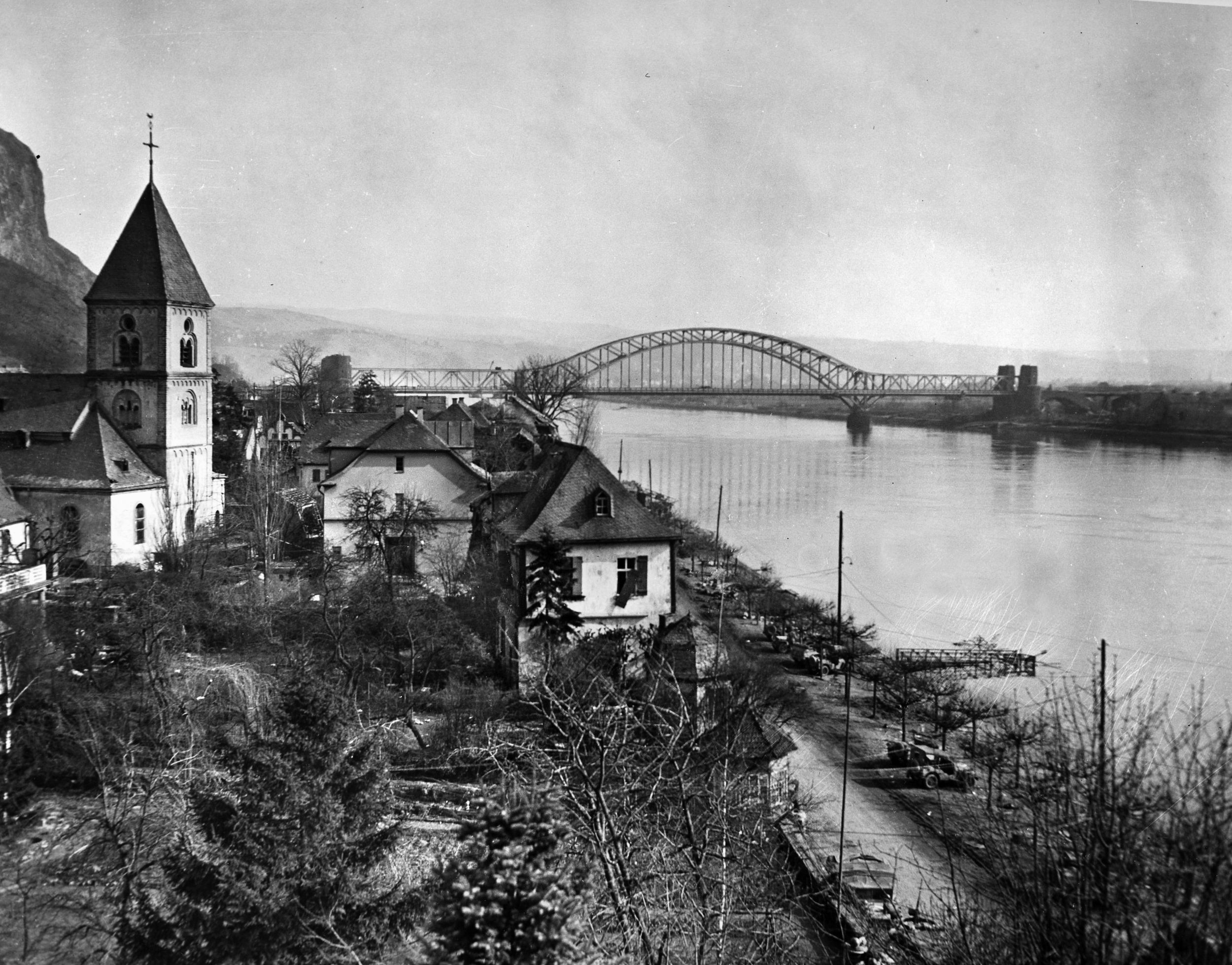

During World War I, First Quartermaster-General Erich Ludendorff of the German General Staff advocated for the building of a railroad bridge at Remagen to facilitate the movement of supplies and reinforcements to the Western Front. Construction of the bridge, which would connect Remagen on the west bank with Erpel on the east, began in 1916 and was concluded in 1919. Four stone piers supported three metal spans totaling 1,069 feet—earth access ramps on each bank extended the overall length of the Ludendorff Bridge to 1,300 feet.

The bridge carried two sets of railroad tracks with catwalks on either side. Wooden planking could be placed over one set of tracks to allow vehicular traffic when needed. From the east, the tracks onto the bridge ran from a tunnel cut through the Erpeler Ley ridge, looming 600 feet above the river. Castle-like stone towers with embrasures for machine guns, two on each end, guarded the approaches to the bridge.

Like other Rhine bridges, the Ludendorff Bridge was prepared for demolition. Zinc-lined boxes with explosive charges were emplaced strategically to blow up the bridge and drop it into the river. The electrical cable for the demolition fuse was encased in steel metal pipes, and the terminal for the ignition switch was located just inside the entrance to the Erpeler Ley tunnel. A hand-activated primer cord provided a backup in case the electrical means of ignition failed. A separate explosive charge with a dedicated ignition switch was placed under the western bridge access ramp. Engineers periodically tested ignition circuits to make sure they functioned properly.

After an American bomb struck the Mulheim Bridge in Cologne on October 15, 1944, setting off its demolition charges and destroying the bridge, German dictator Adolf Hitler ordered all bridge demolition charges removed to prevent further such incidents. The charges were to be replaced when the Allies were within five miles of a bridge and even then a bridge could be destroyed only by a written order from the commanding officer of the defensive sector. Needing scapegoats, Hitler ordered the officers “responsible” for the loss of the Mulheim Bridge court-martialed. As a result, officers in charge of other bridges were anxious about the consequences of blowing them too soon or letting them fall into enemy hands.

Initially, the Remagen sector fell within the area of responsibility of the Wehrkreis XII Nord (War District 12 North). However, as fighting drew closer, responsibility passed to a field command, in this case, Field Marshal Walter Model’s Army Group B. On March 1, Model appointed Maj. Gen. Walter Botsch, commander of the shattered 18. Volksgrenadier Division, to oversee defenses of bridges in the Bonn-Remagen sector.

Upon inspecting the Ludendorff Bridge, Botsch found its defenses woefully inadequate and command structure jumbled. While Captain Willie Bratge, a hardened combat veteran with two Iron Crosses, was in nominal command of the Remagen defensive area, collocated units with their own chains of command were only required to cooperate with him. The only unit directly under Bratge’s command was his own convalescent company of 36 men unfit for front-line duty.

Engineer Captain Karl Freisenhahn, an easy-going fifty-year-old WWI veteran commanding a company of 120 older reservists, was responsible for maintaining and preparing the bridge for demolition. The two 20mm anti-aircraft flak batteries deployed on top of the Erpler Ley belonged to the Luftwaffe and were not subordinate to either Bratge or Friesenhahn. There was also a hodgepodge of local Volkssturm and Hitler Youth, the National Labor Service, and some service support detachments, all of dubious combat value and with their own chains of command.

Neither Bratge nor Friesenhahn had dedicated transport or radios, relying on one military and one civilian telephone line for communications. However, neither line was wholly reliable and suffered frequent service interruptions and delays.

Botsch immediately requested at least one infantry regiment and additional anti-aircraft assets to bolster the defenses of the Ludendorff Bridge. He was promised a heavy anti-aircraft battalion which never arrived.

During the night of March 5-6, Maj. Gen. John Millikin, commander of the U.S. III Corps from the First Army, received the mission to advance in the sector from Bonn to Bad Neuenahr-Ahweiler on the Ahr River, the Rhine’s western tributary. Milliken was to clear the west bank of the Rhine and await a link up with Patton’s Third Army. Remagen fell within the area of operations of Maj. Gen. John Leonard’s 9th Armored Division.

During the night of March 6-7, as Leonard’s 9th Armored Division was closing on Remagen, Botsch was reassigned to command the LIII Armeekorps. At 1 a.m. on March 7, General Otto Hitzfeld, commander of the LXII Armeekorps, received orders assigning him the responsibility for defending Remagen. Botsch’s departure to his new command was so sudden he did not have an opportunity to brief Hitzfeld. Defensive lines of Hitzfeld’s corps had been penetrated in multiple locations by the fast-moving American formations and Brig. Gen. William Hoge’s Combat Command B from the 9th Armored Division was already closer to Remagen than Hitzfeld’s headquarters.

Having no knowledge of the situation at Remagen, Hitzeld dispatched his adjutant Major Hans Scheller at 1:30 a.m. to take charge of the Ludendorff Bridge’s defenses, prepare it for demolition, and destroy the bridge, if needed, at Scheller’s discretion.

Scheller set off in a staff car, accompanied by a radio truck. In the darkness, detouring around advancing American units, Scheller’s small column became separated. Unable to get through, the radio truck turned back to Hitzfeld’s headquarters, denying Scheller communications with his superior.

On the morning of March 7, Hoge organized his command into two columns. The southern column was to secure crossings over the Ahr River. The northern column under Lt. Col. Leonard Engeman, composed of elements from the 14th Tank Battalion, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, and 9th Armored Engineer Battalion, received orders to take Remagen. While Engeman’s specific orders did not call for capturing the Ludendorff Bridge, he was to attempt to “grab it” if the bridge was still standing. Engeman’s departure in a drizzling rain was delayed until 10 a.m. while combat engineers cleared the streets of Meckenheim of rubble from the previous day’s fighting.

Major Scheller arrived at the bridge at 11:15 a.m. No sooner had Scheller informed Bratge he was taking over command at the bridge when sounds of rifle and machine gun fire came from the woods north of Remagen. He ordered the bridge readied for demolition as the retreating Germans continued moving east over the bridge. As Friesenhahn’s engineers made the final preparations, Luftwaffe Lieutenant Karl Peters arrived with a battery of secret new Flakwerfer 44 Föhngeräte multiple rocket launchers. He requested Scheller to delay the bridge’s destruction a little longer to allow more German units to escape.

Karin Loef, a resident of Erpel, watched the exhausted and dejected German soldiers pour across the bridge. “I could not help comparing it to Napoleon’s retreat,” she remembered, “The older ones could hardly march on; their eyes were cast down onto the ground, they seemed to simply stumble on without any hope.”

Around the same time, additional explosives requested by Friesenhanhn arrived by truck. To his disappointment, instead of the 600 kilograms he asked for, only 300 arrived. Even then, the new explosive was Donarit, a weaker industrial grade composed of 70 percent ammonium nitrate, 25 percent trinitrotoluene (TNT), and five percent nitroglycerine.

At 1 p.m., Engeman’s column emerged from the woods on the cliffs overlooking the Rhine north of Remagen, a mile away from the Ludendorff Bridge. Engeman could clearly see a lot of activity around the bridge, with German soldiers and military vehicles intermixed with civilians moving across.

Continuing the advance, Engeman sent 2nd Lt. Karl Timmermann’s dismounted A Company, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, down to Remagen at 1:50 p.m., followed thirty minutes later by 2nd Lt. John Grimball’s platoon of new heavy T26 Pershing tanks from the 14th Tank Battalion. March 7 was Timmermann’s first day in command of the A Company, the previous commander having been hit the day before during the fight for Meckenheim. Besides Timmermann, there were two other officers in the company, 2nd LTs Burrows and David Gardner, the 2nd and antitank platoon leaders. Staff Sergeants Michael Chinchar and Joseph DeLisio, for lack of officers, commanded the 1st and 3rd Platoons.

Scheller ordered his men to the east bank of the Rhine at the Americans’ approach, leaving only Bratge’s company to defend Remagen. The explosives firing circuit was tested and found operational and German traffic going both ways was halted.

Grimball’s tanks quickly overtook Timmermann’s men advancing on foot and raced through the town toward the bridge. The A Company followed Remagen’s main road, encountering only minor resistance from the few German soldiers still in town and ineffectual fire from the 20mm flak guns from the top of the Erpeler Ley. Captain Bratge’s 36-man company melted away, with only Bratge and several men escaping to the Erpel side.

At 3:15 p.m., as the American tanks reached the western end of the Ludendorff Bridge, Scheller gave the command to detonate the demolition charge under the west approach ramp. Sending a fountain of debris in the air, the resulting explosion created a 30-foot trench in the earthen ramp, sufficient to halt the tanks but also providing good shelter for Timmermann’s men.

As Grimball’s tanks and Timmermann’s infantry began exchanging fire with the Germans on the east bank, news began circulating that a captured German soldier reported that the Ludendorff Bridge was going to be blown up at 4 p.m. This was highly unlikely since the bridge’s demolition was solely based on Scheller’s judgment and not on a schedule. Nonetheless, the rumor reached Hoge, who immediately ordered Engeman to take the bridge.

Engeman passed the word down to Major Deevers, commander of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, who ordered Timmermann to take his company across the bridge. To give them cover, American mortars began firing white phosphorus rounds at the German side of the bridge while the tanks engaged the Germans in their defensive positions.

Around 3:30 p.m., with American shells blanketing the area between the east end of the bridge and the tunnel, Scheller ordered Friesenhahn to blow the bridge. From his position just inside the tunnel, Friesenhahn personally triggered the ignition switch, but nothing happened. He then called for volunteers to set off the secondary charge by hand. Corporal Anton Faust ran out of the tunnel, dashed the 100 yards under fire to the east end of the bridge, and set off the charge by hand.

The bridge seemed to jump into the air, but when the dust settled, the bridge was still standing. Timmermann’s men, who were about to enter the bridge, dove for cover. When Timmermann gave orders to continue, the men hesitated. It took great effort to get them to enter the bridge they expected to collapse at any moment.

Staff Sergeant Joseph DeLisio’s 3rd Platoon led the way. Directly behind the 3rd Platoon came three combat engineers from the 9th Armored Engineer Battalion, First Lieutenant Hugh Mott, Staff Sergeant John Reynolds, and Sergeant Eugene Dorland. As DeLisio’s men rushed from girder to girder, the engineers began locating explosive charges, cutting the wires, and tossing the charges into the water.

German soldiers on a half-sunken barge approximately 200 meters from the bridge opened fire on Timmermann’s men but were quickly silenced by Pershing tanks.

As G.I.s got closer to the east end of the bridge, machine gun fire erupted from one of the towers ahead of them. The flak batteries on top of the Erpeler Lay also opened fire, but most anti-aircraft guns could not depress low enough to be effective.

DeLisio charged into one of the towers, where he found several German soldiers attempting to clear a jammed machine gun. After DeLisio fired several shots, the Germans surrendered. Sergeant Chinchar and privates Samele and Massie entered the second tower, and the German soldiers there also surrendered.

Sergeant Alexander Drabik, a squad leader in the 3rd Platoon, was the first American soldier across the Rhine. “We ran down the middle of the bridge, shouting as we went. I didn’t stop because I knew that if I kept moving, they couldn’t hit me. My men were in squad column, and not one of them was hit. We took cover in some bomb craters. Then we just sat and waited for others to come. That’s the way it was,” Drabik later recalled. Timmermann was the tenth man across and the first American officer to step onto the east bank of the Rhine.

By 3:50 p.m., all of Timmermann’s company was across the bridge. Despite a flurry of fire directed at them, not one of the G.I.s was hit crossing the bridge. While Timmermann deployed his three platoons around the east end of the bridge, Lieutenant Mott and his two sergeants methodically continued searching for additional demolition charges.

Timmermann sent Sgt. DeLisio with four soldiers to check out the tunnel. Several shots rang out from the tunnel and after DeLisio and his men pumped several shots in return, several German soldiers ran out with their hands up. DeLisio advanced a few meters into the tunnel, destroyed the ignition switch box, and returned to Timmermann to report that the tunnel was clear. He did not see several hundred German civilians and soldiers further down the tunnel hunkering down in the darkness.

Timmermann was painfully aware his lone company was in a dangerous position. There was still sporadic fire coming from the top of Erpeler Ley. Timmermann sent Lieutenant Burrows with his 2nd Platoon to clear the top of the cliff. The slope was extremely steep, and several G.I.s fell and were seriously injured. Several more were wounded by German fire. “Taking Remagen and crossing the bridge was a breeze compared to climbing that hill,” Lieutenant Burrowed later recalled. After clearing the top of the Erpeler Ley, Lieutenant Burrows pushed his platoon to the spot overlooking the east end of the tunnel and halted there.

At 4:15 p.m., as Engeman was pushing the other two companies from the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion across the bridge, a liaison officer from the 9th Armored Division’s headquarters reached Hoge. His orders, dated 10:50 a.m., were to continue south along the Rhine’s west bank to “seize or, if necessary, construct at least one bridge over the Ahr River in the Combat Command B zone and continue to advance approximately five kilometers south of the Ahr; halt there and wait for further orders.”

On his initiative, Hoge continued moving the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion across until he could confirm his orders. At 4:50 p.m., Hoge met Leonard at Birresdorft, five miles west of Remagen. Apprised of the new development, Leonard directed Hoge to secure the bridgehead. The closest units, the 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion, the 1st Battalion from the 310th Infantry Regiment, one tank destroyer company, a reconnaissance troop, and an engineer platoon, were redirected to the Ludendorff Bridge.

While Hoge was conferring with Leonard, German officers bottled up inside the Erpeler Ley tunnel were getting desperate. Out of contact with higher headquarters, Major Scheller grabbed a bicycle and rode off to find the nearest German unit with a radio. Discovering Scheller gone, Bratge sent a motorcycle messenger for help. However, fire by American soldiers from above the eastern end of the tunnel cut Bratge’s messenger down before he got away.

By 5:30 p.m., with the Americans controlling both ends of the tunnel and realizing the hopeless situation, Bratge and Friesenhahn ordered their men to lay down their weapons. Intermingled with civilians, German soldiers began leaving the tunnel with their arms up. Among German equipment captured by Americans at the east end of the bridge was one Flakwerfer 44 Föhngeräte multiple rocket launcher from Lieutenant Karl Peters’ battery.

Without heavy weapons, the American bridgehead at the east end of the bridge was in a precarious position. A plow-equipped tank from the 14th Tank Battalion bulldozed the crater in the western approach ramp while the combat engineer platoon placed additional planking over the bridge’s roadway. After midnight, in heavy rain, a tank company and one of the tank destroyers made it across before another tank destroyer slipped off the roadway, halting the traffic for several hours. The one-way traffic resumed at 5:30 a.m. on March 8 once the disabled vehicle was winched out.

The word about the bridge capture quickly went up the chain. “Shove everything you can across it, Courtney, and button the bridgehead tightly,” Bradley ordered Hodges upon receiving the news. In turn, Bradley reached out to Eisenhower. “Hold on to it, Brad,” Eisenhower responded, “Get across with everything you need —but make certain you hold that bridgehead.”

All attention now shifted to the Ludendorff Bridge. Hodges redirected Millikin’s 9th and 78th Infantry Divisions to Remagen, as well as III Corps’ and First Army’s artillery, air defense, and engineering assets.

Discovering the loss of the Ludendorf Bridge, Major August Kraft, commander of the 3rd Battalion from Landes Pioneer Regiment 12, and regimental commander Major Herbert Strobel organized a scratch force of some 100 engineers and air-defense gunners. Bringing along explosives, Strobel’s force began moving toward the bridge shortly after midnight. They ran into the forward pickets of the 14th Tank Battalion and 1st/310th Infantry Regiment. Strobel’s force was dispersed in a series of confused clashes in the dark, and the majority was taken prisoner. By 7 a.m. on March 8, the dismounted 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion was also on the east bank and took over the northern sector of the bridgehead at Erpel. Three field artillery and one air-defense artillery battalions took up positions on the west bank of the Rhine.

On the morning of March 8, Model arrived in Bonn to receive the news about the calamity at Remagen. He ordered General Fritz Bayerlein, commander of the elite Panzer Lehr Division, to organize a task force consisting of remnants of his own division together with the 9th Panzer Division, the 106th Panzer Brigade, and the 11th Panzer Division. The four once-formidable formations now barely numbered sixty tanks and 12,000 men, critically short on fuel and ammunition. Bayerlein wanted to gather the four units into one powerful fist, but Model ordered him to commit the tank formations as soon as they became available. The 11th Panzer Division was so short on fuel that it could not get underway until March 11.

Finding out about the loss of the Ludendorff Bridge and the American breakthrough to the east bank of the Rhine, Hitler flew into a rage. He immediately dismissed Model and replaced him with Field Marshal Albert Kesselring. However, Kesselring kept Model in operational command of Army Group B.

Majors Scheller, Kraft, Strobel, Captain Friesenhahn, and Lieutenant Peters were arrested and court-martialed. Captain Bratge was tried in absentia. Majors Scheller, Kraft, and Strobel were found guilty of dereliction of duty and Lt. Peters of allowing one of his secret rocket launchers to fall into enemy hands. The four unfortunate officers were promptly shot. Bratge was also found guilty, but his conviction was moot since he was an American POW. Friesenhahm, also in American hands, was absolved of any guilt.

While the weak German Volkssturm and rear echelon units established a defensive perimeter around the bridgehead, German artillery began the bombardment of the bridge. The hilly terrain provided good observation points for German artillery observers, and during the next two days, multiple direct hits were scored on the bridge.

Starting late on March 8, the Germans began launching ground counterattacks. Rain and low clouds grounded fighter-bombers, but the German air force launched a raid with 10 Ju-88 Stukas against the bridge, eight of which were shot down. The increasing flow of American reinforcements created bottlenecks and traffic jams at Remagen, resulting in heavy casualties from German artillery. The open space between Remagen and the west end of the bridge became known as the Dead Man’s Corner.

By the end of the day, over 8,000 American troops had crossed the Ludendorff Bridge. While the infantry steadily and cautiously expanded the bridgehead in rugged terrain on the east bank, American engineering assets began arriving in force at Remagen.

The American commanders expected the damaged Ludendorff Bridge to collapse at any time. On the morning of March 9, the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion (ECB) began constructing a treadway bridge roughly 400 meters downstream from the Ludendorff Bridge. Combat engineers worked in full view of German artillery observers on the east bank, and German shells began falling on the equipment assembly and bridge construction site almost immediately. The forward end of the treadway bridge where the floating sections were attached was called the Suicide Point. The name was justified when around 1 p.m., a German round scored a direct hit on the Suicide Point, killing one man and wounding five more.

Despite continuous German fire, the engineers assembled 300 feet of the floating bridge by the time darkness fell, and pontoon boats with outboard motors began ferrying troops to the eastern bank.

On the morning of March 10, the 276th ECB from the III Corps relieved the exhausted 9th Armored Engineer Battalion. Before leaving, the men of the 9th erected a sign, “Cross the Rhine With Dry Feet, Courtesy of the 9th Armored Division.”

The mission of the 276th ECB was to repair damages to the bridge’s western approach ramp and make the bridge passable for vehicular traffic. “[The] single charge completely destroyed a critical panel joint in the upstream truss, almost directly over the right river pier… forcing the truss 4 inches out of alignment,” noted Lt. Col. Clayton Rust, commander of the 276th ECB, “Restoration of the bridge to full strength was not intended at the time; the immediate goal was to provide only sufficient strength to support the dead load and Class 70 one-way traffic. Full repairs were to be made later when more adequate equipment and skills could be mobilized.” A detachment from the 1058th Engineer Port Construction and Repair Group assisted the 276th ECB with specialized equipment.

Another engineer battalion placed three lines of net and log booms upstream to prevent the Germans from floating down mines and boats loaded with explosives. The nets were also to prevent underwater attacks by German frogmen after such an attempt was made in September 1944 when the Germans tried to blow up two bridges at Nijmegen on the Waal River. The Germans blew up one bridge in that attempt while the 12-man team was killed or captured.

As more and more American units crossed the Rhine, the bridgehead slowly expanded in rugged terrain against stiffening German resistance and local counterattacks involving tanks and self-propelled guns. The air was thick with incoming and outgoing artillery. However, German artillery fire began to slacken as the expanding American bridgehead pushed German artillery positions farther east, and a German artillery observer with a radio was captured in Remagen.

On March 12, two treadway and two pontoon bridges were fully operational. With multiple ferries shuttling men, equipment, and vehicles to the eastern bank, the Ludendorff Bridge was closed for repairs. It is unknown why the explosive charges failed to destroy the bridge on March 7. The electrical circuit was tested shortly before the American arrival. It is possible that the shelling from T26 Pershing tanks, tank destroyers, and mortars cut one of the pipes containing the fuse.

With the weather slightly improving, between March 12 and 13, waves of German aircraft totaling 91 machines conducted 58 raids against the thickening American air defense umbrella. Twenty-six German planes were shot down, with eight more limping away trailing smoke. The attacks on March 13 included Ar-234 jet bombers, accompanied by Me-262 jet fighters from III.Kampfgeschwader 76. The improved weather also allowed American P-38s to fly continuous air cover of the bridge.

Four tanks equipped with searchlights called Canal Defense Lights took up positions on both sides of the Rhine to scan and illuminate the river. At the same time, three LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) began patrolling upriver and dropping depth charges at intervals to interdict German midget submarines and combat swimmers.

At 9:45 a.m. on March 17, the first German V2 rocket hit near Remagen. The impact of the 46-ft. long supersonic missile carrying a 2,200-pound warhead shook the ground. A total of 11 rockets from launch sites near Hellendoorn in the Netherlands, redirected from being fired at Antwerp in Belgium, continued landing at regular intervals through the day until 9:45 p.m.

Being area-effect weapons, most of the V2 rockets landed within several miles of the Ludendorff Bridge, destroying several farms and killing civilians and farm animals. One rocket landed on the west side of Remagen, striking a two-story inn housing the command post of B Company, 284th ECB, killing three men and wounding 31 others.

Around 3 p.m. on March 17, engineers working on the bridge heard sharp cracks of rivets breaking. The arch of the Ludendorff Bridge collapsed, taking the adjoining bridge spans and engineers working on it into the river with it.

“I was out on the bridge but only at the [west] edge. When it came down, the noise and the sight of the falling soldiers was very frightening. I was afraid that the rest of the bridge would go, and all of us would meet the same end,” remembered Private John Morgado from the 276th ECB, “I looked down to see the men, several of whom I knew, trying to keep their heads above the water, but because they had on heavy gear and the river was flowing so swiftly they couldn’t.”

Downstream, the men from the 291st ECB rushed onto their treadway bridge to intercept the debris pieces and guide them between the floats. Many engineers jumped into the water to rescue the injured men being swept downstream. They saved 18 survivors.

Six soldiers from the 276th ECB died; 11 were missing and presumed drowned; 60 were injured, and three later succumbed to their injuries. Lt. Col. Rust, who fell into the water but made it out on his own, described the event as the “complete decimation of the unit command.” The battalion’s executive officer, two company commanders, three platoon leaders, and six platoon sergeants were among the dead and missing. In the 1058th Port Construction and Repair Group, its commander Major Carr was killed, seven men were missing, and six more were injured.

“The main reason for the collapse of the Ludendorff Bridge, most engineers believed, was the break in the bottom chord of the upstream truss from the German demolition charge of March 7. This forced the downstream truss to carry the whole load and subjected the entire bridge to a twisting action,” wrote Captain James Cooke, structural engineering expert, “The strain on the truss was increased by the weight of the timber decking American engineers had added to the flooring, by continuous bridge traffic between 7 and 12 March, and by engineer repairs between 12 and 17 March—hammering, welding, and moving heavy cranes and trucks.”

During the night of March 17-18, seven German combat swimmers from SS-Kampfschwimmergruppe entered the near-freezing waters of the Rhine. The men, who wore underwater breathing apparatuses, rubber suits, and fins, carried explosives intending to blow the pontoon bridge upriver from the already-collapsed Ludendorff Bridge. Struggling in the strong current, the exhausted frogmen were spotted by American searchlights and fired upon. Several Germans were hit and went under; the rest made it to the bank and were captured.

On March 20, the Germans brought up a super-heavy Karl-Gerät 600mm mortar. After firing 14 rounds at Remagen without significant effect, the weapon was withdrawn.

American presence east of the Rhine could no longer be characterized as a bridgehead but a full-scale breakthrough. Realizing the futility of further counterattacks, Model ordered Bayerlein to pull back. By March 22, leading American units cut the Ruhr-Frankfurt autobahn, allowing three armored divisions to break into operational maneuver space.

For their heroic actions, Lt. Timmermann, sergeants DeLisio and Drabik, and 10 others received the Distinguished Service Cross, and 152 men received the Silver Star.

“We were across the Rhine, on a permanent bridge; the traditional defensive barrier to the heart of Germany was pierced. The final defeat of the enemy, which we had long calculated would be accompanied in the spring and summer campaigning of 1945, was suddenly now, in our minds, just around the corner,” was how Eisenhower described the “Miracle at Remagen” after the war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments