By Victor Kamenir

By the late 1870s, Turkey, the so-called “Sick Man of Europe,” was in terminal decline. While Sultan Abdul Hamid sequestered himself in his palatial compound through paranoid fear of an assassination, the Ottoman Empire was tearing itself apart. National uprisings were flaring all across Serbia, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Montenegro. European countries, led by England and Russia, were clamoring for greater autonomy and rights for the Empire’s Christian subjects.

When the sultan rejected outside interference in Turkey’s internal matters, Czar Alexander II jumped. Loss of prestige from Russia’s defeat during the Crimean War was still fresh in Alexander’s mind. The guise of protecting the Ottoman Empire’s oppressed Christian population provided a convenient pretext for territorial gain in the Balkans. As Peter the Great had wanted his “window to Europe” through the Baltic Sea, so Alexander—in hopes of imitating his famous ancestor’s feat—desired to stretch the Russian Empire to the Mediterranean. On April 24, 1877, Russia and Turkey went to war for the third time in the 19th century.

Russian plans called for finishing the war in one campaigning season, occupying Bulgaria and, if at all possible, capturing the Turkish capital of Constantinople. The Turks also planned to fight offensively, reestablish a firm hold on Romania, and take the war to the Russians in Bessarabia. However, shortly before hostilities commenced, the Turkish high command decided on new plans: The Turks were to fight defensively, using fortresses and other strongpoints to wear down the Russians and only then seek a decisive battle in the field.

Two strong Russian armies, commanded by the czar’s brothers, invaded Ottoman territory from two directions. In Asia, Grand Duke Michael led his 150,000-strong army against the eastern bulwarks of Turkey. In Europe, a 200,000-man force under Grand Duke Nicholas attacked across Romania into Bulgaria, the site of recent Turkish atrocities. The Romanians promptly declared their independence from Turkey and began to enroll volunteers to fight alongside their Russian liberators. The overall Turkish commander in Europe, Abdul-Kerim Nadir Pasha, received many ominous reports of forward Turkish garrisons falling one after another. The Russian invasion was beginning to look like a triumphant march to Constantinople. Then it was brought to a halt at the sleepy Bulgarian town of Plevna.

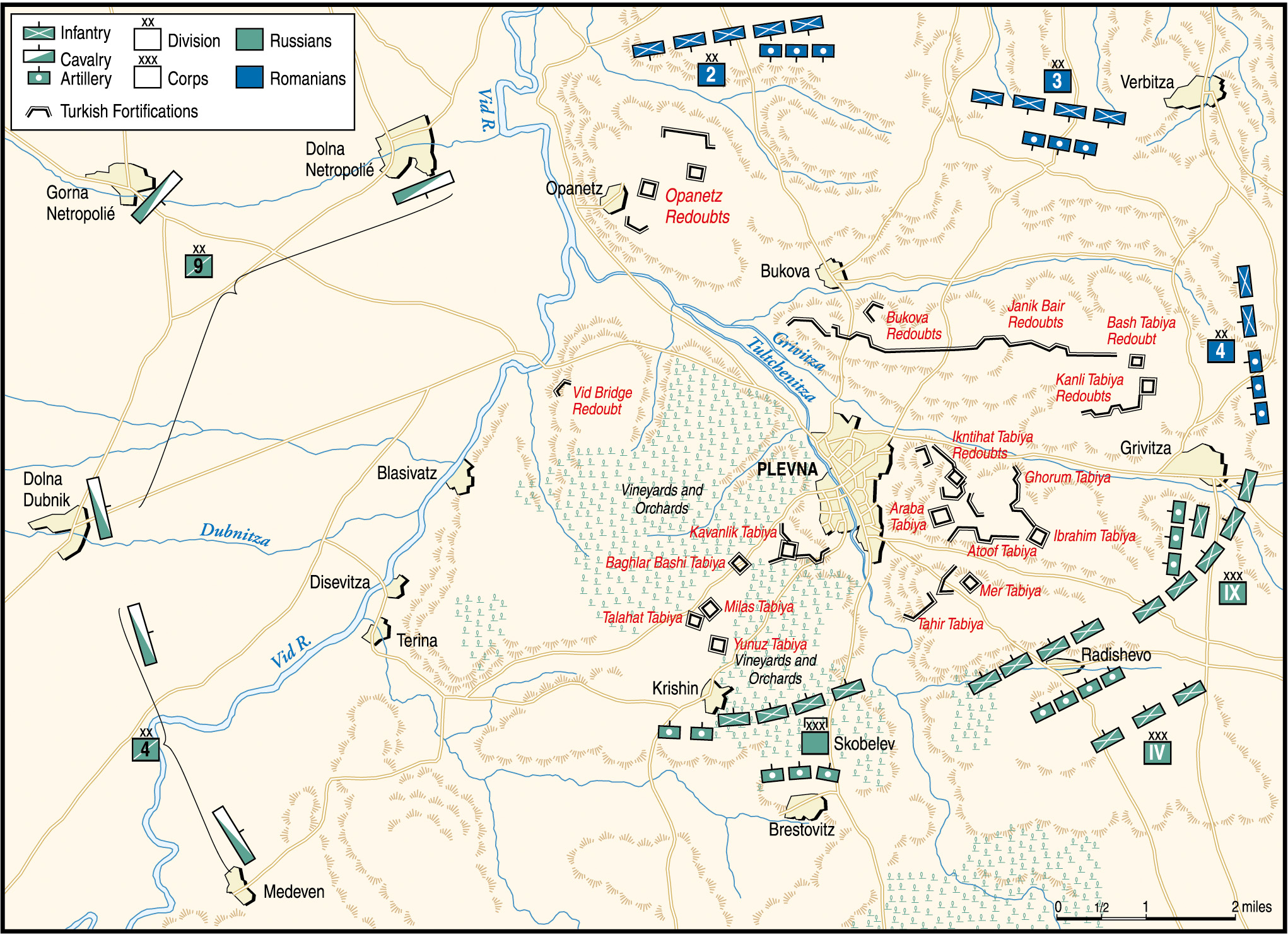

Nestled in a narrow valley, Plevna (modern day Pleven) sits astride a strategic road junction leading to the Bulgarian capital of Sofia and on to Constantinople. Deep ravines, rocky ridges, and steep hillsides surrounded the town on three sides. The Janik Bair Ridge dominated the fourth. Practically undefended, there was no reason why Plevna would not fall to the approaching Russian army.

Unknown to the Russians, they were in a foot race with a Turkish force charging to block their progress. Led by a 40-year-old Crimean War veteran named Osman Pasha, a Turkish corps force-marched 115 miles in seven days from the fortress of Viddin on the Upper Danube. This army comprised 19 infantry battalions, six cavalry squadrons, and nine artillery batteries totaling 12,000 men and 54 guns. Upon arriving at Plevna on June 19, Osman—a short, stocky disciplinarian respected by his troops—immediately conducted a reconnaissance of his surroundings. With the three infantry battalions that comprised the previous garrison and three more battalions that joined him en route, Osman now had 25 infantry battalions under his command.

Not wasting any time, and aided by his chief engineer Tefik Pasha, Osman threw the bulk of his force into digging redoubts, field fortifications, and trenches around the town. Working in shifts around the clock, Turkish troops quickly constructed defensive positions along the Janik Bair Ridge which rose 400 meters above the town. The right flank of this position was anchored on two redoubts just north of Grivitsa Village. These two formidable, mutually supportive fieldworks each held a garrison of a thousand men. Walls 20 feet thick and 20 feet high, with moats and trenches, constituted the main defenses of each redoubt east of Plevna. Food and ammunition were distributed and measures were taken to ensure evacuation of the wounded.

On July 6, Russian advance cavalry pickets soon appeared near the town and Turkish cavalry got the upper hand in several skirmishes. Some enterprising Turkish troopers sold items of looted Russian uniforms and personal possessions in Plevna’s bazaar. Osman Pasha did not interfere with this traditional disposition of Ottoman spoils. He did step in, however, after several Bulgarian stores were looted. The trust of the local population was quickly restored by the quick execution of several wrongdoers.

The bulk of the Russian column sent to capture Plevna arrived on the evening of July 7th. Commanded by Lt. Gen. U.I. Schilder-Schuldner, this detachment comprised 8,600 men and 46 field artillery pieces. The very next morning, Schilder-Schuldner, not bothering to conduct reconnaissance and thinking that Plevna was occupied by only a small Turkish detachment, launched his force in a general assault. The attack was a disaster. After several hours of fruitless charges, the Russian force pulled back to regroup. Over 2,400 men, almost a third of the Russian troops present, were killed or wounded. The Turkish defenders, well entrenched in their redoubts, suffered just several hundred casualties.

After the first unsuccessful assault, a Russian force under General Fabian Kridener concentrated around Plevna and began to gather additional forces for another assault. Incredulously, the Russians did not completely blockade the town, and the Turkish force under Osman Pasha was continuously reinforced and resupplied. By the time the second Russian assault was launched, 22,000 Turks with 58 cannon faced over 36,000 Russians with 176 cannon. The Russian Supreme Headquarters, along with Czar Alexander II and his brother Grand Duke Nicholas, accompanied by a glittering entourage of aides, adjutants, observers, and hangers-on, relocated to Plevna as well.

At 11 am on July 18, under the eyes of the czar, Russian forces launched themselves at Plevna for the second time. Again and again, Turkish defenders armed with American breech-loading Peabody rifles repulsed waves of attacking Russians. The czar threw in 10,000 reinforcements. These fresh Russian troops broke into and occupied a large part of the first line of Turkish trenches. For a moment, it looked like the Russians would emerge victorious, but Osman Pasha was not ready to give up. Driven on by bugles, Turkish reserves countercharged the tired Russian soldiers who thought they had won. After a brief fight, the Russian forces fled the captured trenches and the Turks reoccupied their positions.

The Russians spent a miserable night trying to shake their disordered units into cohesive formations. Over 7,300 Russian soldiers were killed or injured and the night was filled with the horrible sounds of Turks butchering the Russian wounded.

The whole of Europe was shocked by the Turkish success. Among the Ottomans there was celebration; Sultan Abdul Hamid sent Osman Pasha a ceremonial sword encrusted with jewels as a reward.

Near panic was the mood in the Russian camp. Rumors of Turkish pursuit spread like wildfire and thousands of Russian soldiers fled to Romania. Many senior generals advocated for retreat to the north bank of the Danube. The czar unexpectedly showed remarkable backbone and would not budge. The loss of prestige from a failed battle was bad enough. Merciless butchering of the Bulgarian population by Turks would doubtless follow any retreat of the Russian troops, and this was unacceptable to the czar who, just a short time before, proclaimed himself the protector of Christians in the Turkish Empire.

Osman Pasha, however, was not in position for an offensive. Instead, he used the respite to begin a series of elaborate fortifications. He built five new redoubts on the Janik Bair Ridge, all connected by covered trenches. These impressive earthworks had 20-foot-thick walls and were seven feet tall on the outside. A trench 10 feet deep and 15 feet wide surrounded each redoubt and fields of fire were carefully worked out for mutual support. The redoubts were designed to continue fighting even if surrounded. Each Turkish soldier in the garrisons was issued 600 rifle cartridges, with another 1,000 in ready reserve. Food rations for eight days were issued along with a few cattle on the hoof. Each cannon had 100 shells, and transportation for evacuating the wounded was provided. Each redoubt also had a direct telegraph link to Osman Pasha’s headquarters.

Meanwhile, the Russians were planning a third assault, this one for August 30, the czar’s birthday. Russian engineers constructed a large wooden platform near Grivitsa from which Alexander II would observe the battle. While the Russian soldiers in the valley below, mired in deep mud, gathered themselves for the attack, a food table on the czar’s platform was sagging from the weight of various delicacies, including champagne and caviar.

For four days before the assault Russian guns rained over 30,000 shells on the Turkish positions. Even though hundreds of Turks were killed or wounded, the damages to the earthen fortifications were repaired each night.

The Russian plan for the attack had all the finesse of a sledgehammer: Throw enough men at an objective and one of the human waves climbing over the bodies of the preceding ones is bound to achieve victory. Stuck in the glory days of the Napoleonic Wars, the Russian high command failed to take into account the effect that well-motivated, well-entrenched troops armed with modern breech-loading weapons would have on massed columns attacking over open ground.

Thick fog and rain delayed the Russian attack until 3 pm. At that time, three Russian and Romanian columns struck simultaneously from northeast, southeast, and south. An attack on the southern redoubts was led by General Mikhail Skobelev, the most able and colorful of the Russian commanders.

The assaults from the northeast and southeast quickly bogged down. No one, however, can deny the bravery of the Russian and Romanian soldiers. Mowed down by rapid-firing Turkish guns, and leaving 4,000 of their comrades dead or dying in the mud, they captured one of the northern Grivitza redoubts. Their sacrifice was in vain, however, because the redoubts were sited in such a way that the loss of one did not spell disaster for the rest of the defensive line.

The Russians had better luck against the southern redoubt, built on a low hill close to Plevna itself. Skobelev was able to lead his column of 12,000 men into the dead ground at the bottom of the hill without serious casualties. Then, under cover of the supporting artillery, they charged up the hill. A withering Turkish fire met them and the Russian ranks began to waver, slow, and finally halt within reach of the redoubt. Resplendent in his brilliant white uniform, mounted on a white charger, General Skobelev personally led 3,000 reserves to support their comrades.

His white uniform provided a perfect target for Turkish riflemen, and just as the brave Russian general got close to the redoubt, his horse was shot out from under him. Extricating himself from the mud, Skobelev led his men forward on foot. Their impetuous charge led them into the disputed fortification. Now, the beloved Russian weapon, the bayonet, came into action. Those Turks who did not flee were hunted down amid the ruins of the redoubt. Over 3,000 Russians, roughly 20 percent of the total attacking force, lay killed or wounded, the price for capturing this gateway southern redoubt.

When darkness fell, the Turkish commander began a frantic effort to mount a counterattack the following morning. All the troops that could be spared from the other redoubts were concentrated during the night against Skobelev.

As Turkish artillery from the neighboring redoubts poured murderous fire into Skobelev’s exhausted men, the general sent messenger after messenger to Russian headquarters. He felt that if he was given more fresh troops, he would take Plevna itself the next morning. His pleas fell on deaf ears. After darkness, he rode to headquarters to attempt to convince the high command to give him more troops. Yet, all he was able to secure was some rifle ammunition for the troops he already had.

At dawn the bugles blew and the Turks rushed the captured redoubt. Five attacks broke on the earthen fortification, with Russians and Turks in some places engaged in brutal hand-to-hand combat. While Skobelev and his dogged troops were grimly determined to hold onto their hard-won prize, the generals back at headquarters lost heart and ordered a retreat. Skobelev was incredulous when he read the order, but there was nothing he could do. He left one battalion under command of Major Fyodor M. Gortalov to cover the withdrawal and led the rest of his depleted force back to Russian lines.

Before leaving the redoubt, Skobelev made Gortalov promise to hold on at all costs until the main body could escape. This Gortalov did. Once reaching safety, Skobelev sent a runner to Gortalov with orders to make a break for it. The brave Russian major replied, “Tell General Skobelev, that only death can free the Russian officer from his word.” Releasing his soldiers, Major Gortalov stayed behind with the severely wounded. The next Turkish attack found only Gortalov on top of the parapet, with bared sword, blocking the way. The valiant major and all the Russian wounded were bayoneted without mercy. Thus, by late afternoon, the Turks were once again in the possession of the southern redoubt.

Furious, Skobelev remarked, “Napoleon was happy when one of his marshals could gain a half an hour for him. I held on for 24 hours and they did not take advantage of it.”

The overall Russian and Romanian casualties during this third assault amounted to over 15,000 men. Several factors contributed to the Russian defeat. The Russian artillery, though numerous, was located too far from the town to do significant damage, and it did not provide close support for the attacking infantry. Instead of taking advantage of their numerical superiority, the Russian infantry was not concentrated against any one point; rather, it attacked at many points along the defensive line. The Russian high command was overly preoccupied with the army’s blocking and reinforcement detachments. Only 39 Russian infantry battalions directly participated in the assault, while 68 battalions stood idle, watching the action from afar. Not least of all the reasons for failure, Czar Alexander II personally interfered with planning the attack by allowing the horde of his aides and advisors to bombard the commanders with unsolicited battle plans and advice.

Shocked by the setback and losses, on September 1, Czar Alexander ordered all offensive operations to cease and the army to begin a siege. General Eduard Totleben, who distinguished himself during the defense of Sevastopol in the Crimean War, was placed in charge. The idea was that where bullet and bayonet had failed, starvation would prevail.

Osman Pasha and his Turkish troops, for the time being, might have saved the Ottoman Empire by their determined defense of Plevna. The Russian juggernaut on Constantinople was halted and the Russians were forced to confront a difficult siege in the face of a Balkan winter.

Still, knowing that he had no chance to resist a siege, Osman Pasha telegraphed the sultan for permission to withdraw southward where another Turkish force was assembling near the town of Orkanie. To his astonishment, he received orders to remain in Plevna. Sultan Abdul Hamid was reaping unexpected rewards from his troops’ heroic defense of this small and previously unknown Bulgarian town. The waning Ottoman Empire’s prestige had been given a much needed boost. The Turks in Plevna had bought time, and sympathy for them was running high. As British reporter Rupert Furneaux noted, there was a widespread “glorification of the courage and the valor of the bulldog Turks, and Osman … became the man of the hour. Innumerable dogs, not a few cats, the son of an English peer, and a new type of lavatory pan were christened Osman.” Along with his order to hold, the sultan reported that a large relief army was being assembled and that Osman just needed to hang on.

Faced with the prospect of a protracted siege, Osman Pasha now turned his effort to organizing sufficient food supplies and improving fortifications. Fortunately for him and his troops, the Russian efforts to completely invest Plevna were slow. Several weeks passed before they actually completed the encirclement. During this time, hundreds of wagonloads of supplies and thousands of cattle were driven into the town. The Turkish troops who manned and escorted the convoys remained in Plevna, bringing the numbers of Osman’s troops to almost 60,000. Finally, in a last great stroke, a huge convoy of 1,500 bullock carts slipped into Plevna in mid-October before snow began to fall.

To plug the last hole in the 30-mile circle around the town—that of the southern redoubt controlling the road to Orkanie—the Russians launched an attack by the elite Imperial Guard Corps. The fight for the disputed redoubt raged for eight hours. With roughly 4,000 casualties on each side, the remaining Turkish defenders of the southern redoubt surrendered. Plevna was completely encircled.

Winter set in early and was particularly severe. The Russians continued daily sporadic shelling of the town, and the situation there became serious. Every public building was crammed with wounded. All available firewood, including the town’s vineyards, was burned. Daily rations were whittled to half a pound of bread and a small slice of meat. Cats, dogs, rats and pigeons were hunted for sustenance. Despite the shortage of rations, Osman Pasha ordered that horses and bullocks not be slaughtered for food; they would be needed in case of a breakout. Nevertheless, the morale of Turkish defenders was high, expecting the relief promised by their Sultan Abdul Hamid any day.

In the surrounding Russian encampments, the common soldiers ate adequate, if simple, rations. All the while the notables surrounding the czar and the grand dukes were consuming large quantities of delicacies, served on white tablecloths with silverware.

In early November, hoping to undermine Turkish morale, the Russians sent several prisoners back into Plevna with a selection of the latest European newspapers. The newspapers gave grim accounts of Turkish setbacks on other fronts, particularly in the Caucasus. Undaunted, Osman Pasha returned a message, thanking the Russians for some fresh reading. The Russians continued the psychological warfare by raising large placards with news for the common Turkish soldiers to see. Amused and confident, the Turks used them for target practice.

By the end of November, a relief force was finally being organized in Orkanie. These troops were not like Osman Pasha’s hard-fighting soldiers. Disordered and under weak leadership, they ran during the first fight with the Russian advance guard. Hearing of it, Osman Pasha decided that it was now up to him to save what remained of his troops. Not even thinking of surrender, he began to make secret preparations for a breakout.

Under cover of darkness, Turkish defenders, their spirits rejuvenated by the prospect of action, began to reposition artillery and supplies. Troops were shifted to the areas of expected fighting and even the lightly wounded soldiers left the hospitals to rejoin their units. Knowing that the Bulgarians would surely massacre any Turkish civilians left behind, provisions were made to bring them along. Realizing it would be impossible to evacuate seriously wounded and sick soldiers, Osman Pasha obtained the promise of senior leaders of the Bulgarian Church that the wounded would be humanely treated.

Noel Barber wrote, “As the moment of the breakout arrived, the wheels of the gun carriages were greased and wrapped in straw to deaden any sound. Each man was issued with three days’ rations and a pair of sandals. Water, ammunition, forage were loaded, together with the last remains of food. When the troops were slowly withdrawn from the redoubts, life-sized dummies were placed in the trenches to delude the Russians.”

The Turks almost achieved surprise. The Russians were so confident in their encirclement of the town that no efforts were made to strengthen the southern sector, the most logical direction for any Turkish attempts to either break out or bring in reinforcements. At the last minute, General Skobelev received news from a spy that an attempted escape was under way. As the Russians rushed troops to the threatened southern sector, 2,000 Turkish volunteers, personally led by Osman Pasha, charged the Russian lines. The attack was so sudden and furious that one Russian regiment was severely mauled and the inner ring of the encirclement was breached.

Without pause, Osman Pasha fed more troops into the fight in an effort to pry open the outer defensive ring. By now, the alerted Russians sent fresh troops, including the Imperial Guard Corps, into the fight. A fierce struggle, often hand-to-hand, raged on the frozen hillsides. Then, just as the superior numbers of the Russians began to blunt the frantic Turkish efforts, disaster struck the Turks. Mounted on a horse, right in the thick of fighting, Osman Pasha was hit by a bullet. Even though it was a light leg wound, he was knocked off his horse. The nearby Turks saw their beloved general fall and the word spread like wildfire that Osman Pasha had been killed. The Turkish troops began to break contact and retreat back into Plevna. Following on the heels of the fleeing Turks, a Russian counterattack led by Skobelev captured several Turkish redoubts. Almost 2,000 Russians and 6,000 Turks fell in the breakout attempt. Any hope of defending the town was gone and after 143 days of heroic defense, the wounded Osman Pasha and his forces surrendered.

Osman Pasha was treated with the greatest respect by the victorious Russians. Numerous high-ranking officers paid their respects and congratulated him on his heroic defense. Even Czar Alexander II invited him to share a lunch and graciously returned to the Turkish general his surrendered sword. With all possible courtesies, Osman Pasha, accompanied by a several aides, was sent into internment in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov for the duration of the war.

The fate reserved for the rank-and-file Turkish soldiers was not so kind. Over 45,000 surviving soldiers were kept in open-air makeshift holding pens for two weeks with almost no food or medical supplies. Three thousand of them died even before they set off on foot to prisoner of war camps in Russia. Only 15,000 Turkish soldiers reached their destinations, the rest perished in the snow. Moreover, Bulgarian church elders did not keep their promise to safeguard the Turkish wounded left behind in Plevna. They stood idle as jubilant Bulgarians massacred several hundred seriously wounded Turks who had been entrusted to their care.

The fall of Plevna freed almost 150,000 Russian soldiers. Not waiting for the spring campaigning season, Russian strategists resumed their drive to Constantinople. One after another, important Turkish strongholds such as Sofia and Adrianopole fell. On January 31, 1878, Russian and Turkish diplomats signed an armistice.

Worried by the prospect of Russia gaining too much power, European states stepped in to secure the best possible terms for Turkey. The consequences of the interference were far reaching. Under condition of the Peace of San Stefano—brokered by Britain and Germany—Bulgaria was divided into three states. Bessarabia was transferred from Romania to Russia, while Bosnia and Herzegovina were given to Austria. This fracturing of Balkan states was a major cause of World War I. Great Britain, which did not lose a single soldier in the struggle, was able to snatch the island of Cyprus for itself.

Remarkably, the Ottoman Empire managed to survive the onslaught intact, with only minimal territory lost. Creaking along, it lasted until 1924, outliving the Austrian and German empires, as well as its great nemesis Imperial Russia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments