By Blaine Taylor

The British Army of soldiers, Royal Marines and naval infantry—actually sailors from His Majesty’s Navy fighting on dry land with musket, pike and cutlass—were marching full-tilt for the capital of the United States this hot, sweltering August 24, 1814. The year marked the first that the United States had been invaded by a foreign foe.

The Administration of President James Madison, Secretary of State James Monroe, and Secretary of War John Armstrong had done shockingly little to prepare for a British invasion in force except to appoint a Baltimore lawyer and Mason named Gen. William H. Winder as the commander of the Federal 10th Military District of Washington, Virginia, and Maryland.

When the Governor of Maryland, Levin Winder (the General’s uncle), pleaded for Regular Army reinforcements to repel an expected invasion of the free state, the national government told Annapolis to fend for itself. There was a federal garrison at Baltimore’s Ft. McHenry, but that was all. Armstrong was firm in the belief that, when and if an invasion came, the nation could well and ably defend itself with a call-out of the militias that had helped bloody the British at Lexington and Concord in the Revolutionary War. Indeed, all of the top members of the administration and most of the generals of the Regular Army were veterans of that war. But their war experience paled in face to that of the British commanders; King George’s officers had fought around the world for more than 15 years against the forces of the great Napoleon.

Moreover, the administration chose to ignore the overwhelming evidence that had accumulated since war had been declared against Great Britain in June 1812, that the Royal Navy and its marines and sailors could strike with impunity up and down the Chesapeake Bay. The fact that this had not yet occurred simply owed to the fact that Rear Admiral George Cockburn had lacked a strong force of British Regular Army Redcoats. This changed with Napoleon’s defeat in Europe in April 1814.

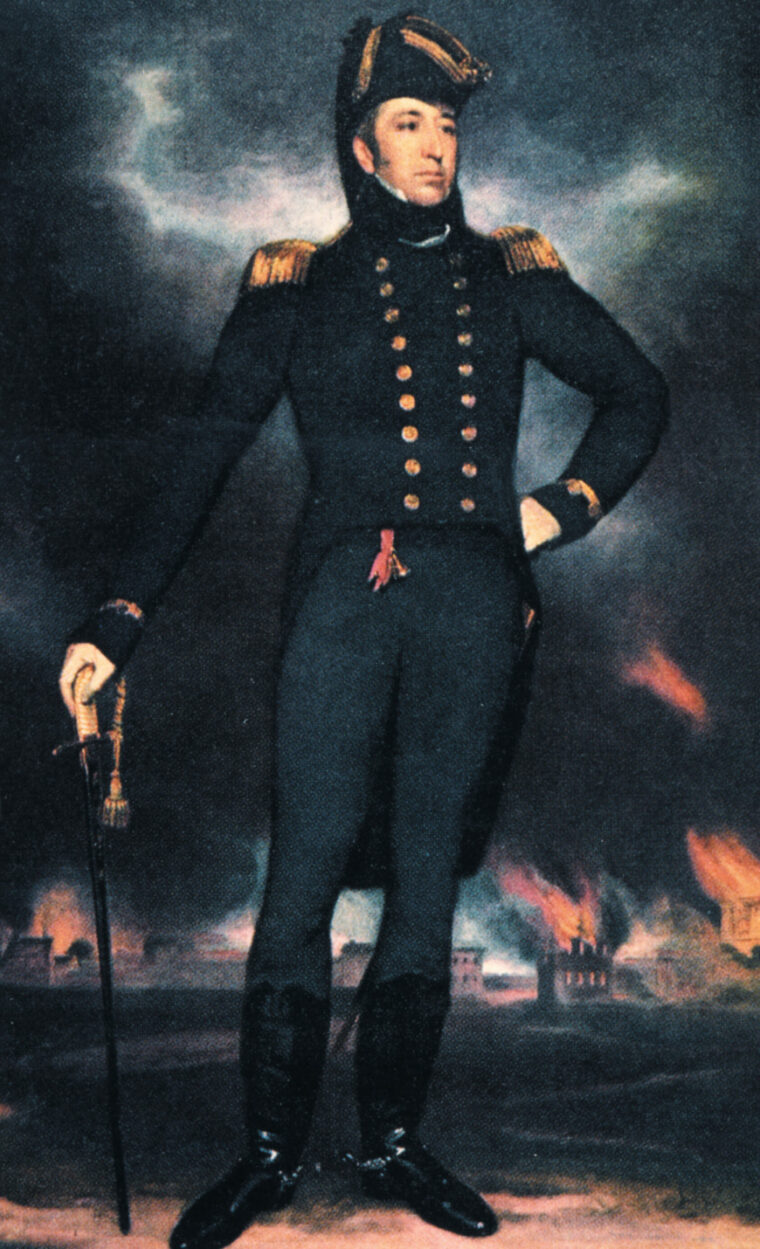

Indeed, as it happened, the Americans called out their defending forces only when the enemy was already on their soil in Maryland. The militiamen literally picked up their arms, mustered and marched off to battle against the mightiest, best-trained, and most well-armed army on Earth. Leading this army—the one Admiral Cockburn had so long awaited—was Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, an aggressive soldier in Europe against Napoleon. As was the tenor of the times among the British, Ross regarded the Americans with paternal derision as England’s country cousins.

Ross had been nominated for the American command after the famed Duke of Wellington had turned it down, and he certainly planned no serious invasion of the American heartland. Still fresh in British memories were the defeats of General Edward Braddock in the French and Indian War, that of Saratoga in 1777, and Yorktown in 1781.

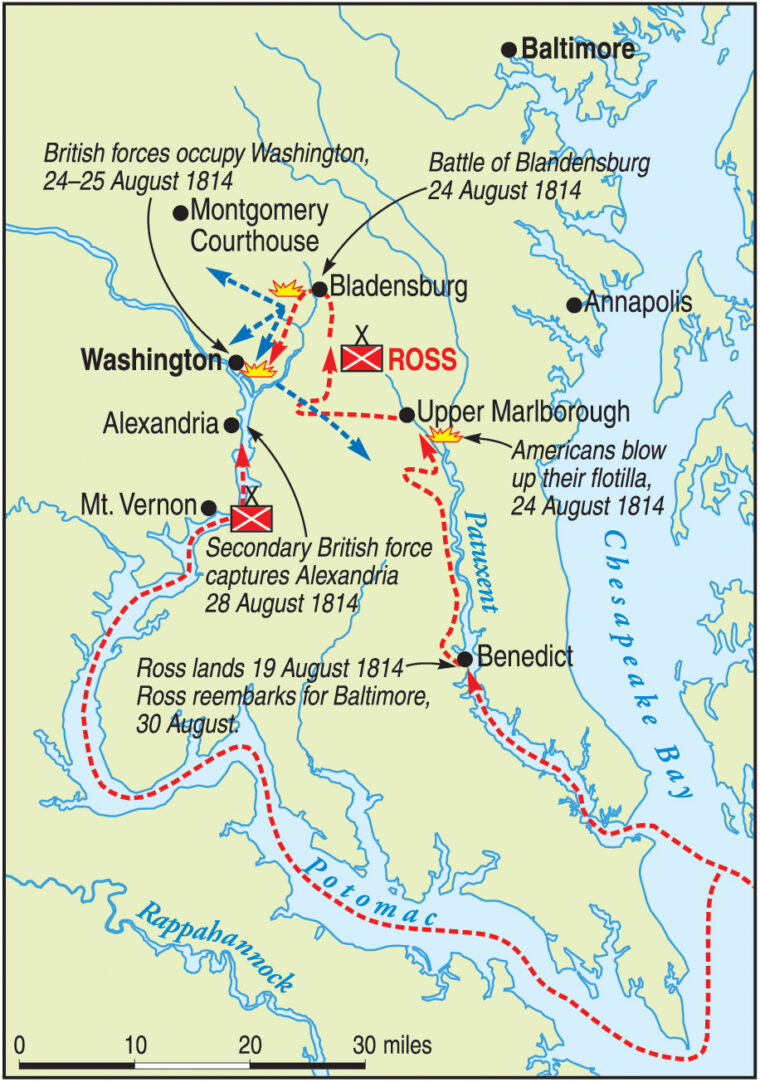

Ross’s mission was to assist Admiral Cockburn in the taking and burning of Annapolis and Baltimore, before perhaps attacking the cities of Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. The Admiral, however, had further ideas of conquest. Although his first priority was to find and sink the Chesapeake flotilla of American privateer commodore Joshua Barney of Maryland, he also wanted to push on to take the Yankee capital and end the war for good.

His main problem was to convince the more cautious Ross that this could be done with minimum loss. The British command structure was such that the admiral commanded the force at sea, while the general took over once it was on land, making persuasive tact necessary. Another problem was that Ross had always expected a massive American army to appear that would wipe out his army of 3,500 men. To his dying day he never realized that such a host simply didn’t exist along the Atlantic seaboard.

Nevertheless, the joint British force landed ashore at Benedict on the Patuxent River in rural southern Maryland’s Charles County. They set off in search of Barney’s ships.

Two days later, on August 21, General Winder took command of his gathering “army” at a place called the Woodyard–today’s town of Highland Meadows, Maryland. His strength grew hourly as militiamen answered their calls to muster (four-fifths being from Maryland.) Winder would also be joined later by Barney’s 400 sailors and 103 U.S. Marines, the best combat effectives under the commodore’s command. Barney had scuttled his flotilla at Pig Point– near today’s Mt. Pleasant–Maryland, to keep it out of Cockburn’s hands. Ross argued that their mission was accomplished, but the insistent Admiral pressed that the greater prize—Washington, D.C.— had yet to be taken. Reluctantly, the general agreed and the drive began.

Ross had four crack British infantry regiments: the 4th, 21st, 44th, and the 85th. At Upper Marlboro in Prince George’s County, Maryland, he left behind a rear guard of 500 Royal Marines with a six-pounder cannon, and set off for the U. S. capital in earnest.

Commodore Barney’s arrival at Washington at 4 pm on August 22 brought Winder’s force up to 3,400 men. Having noted the destruction of Barney’s flotilla, Cockburn and Ross spent the evening at the home of Maryland physician William Beanes. The two armies were then about a dozen miles apart. Winder’s force was still growing, now to about 4,000 men. That same night—as if he didn’t have enough problems already—Winder was confronted with the arrival of the president, secretary of war and the attorney general. The president ordered a military review the next morning. This took place at Long Old Fields, now Forestville, Maryland, about five miles north of Woodyard. The President, disappointed by the appearance of the motley force, returned to the capital by two o’clock in the afternoon, just about the same time the British were leaving Upper Marlboro and heading for Long Old Fields.

Winder decided to withdraw towards a small Prince George’s County town called Bladensburg on the Anacostia River just outside the capital and there make his stand. More American soldiers had been gathering there since the evening of the 22nd.

These men were all Marylanders—the brigade of Revolutionary War veteran General Tobias Stansbury, and a half-brigade commanded by Lt. Col. Joseph Sterrett, plus two batteries of artillery led by William Pinckney, with a regiment of 800 men under another Revolutionary War veteran, Col. William D. Beall. These additional 3,500 men now gave Winder a grand total of 7,500 troops.

Meanwhile, Secretary Monroe sent the following message to the president: “You had better remove the records.” This message caused an immediate panic in the Federal City (as Washington, D.C., was called in those days). One observer wrote, “I never saw so much distress in my life as today. I am fearful that by 12 o’clock tomorrow this city will not be ours.”

On the afternoon of the 23rd the advance guard of Ross’s column collided with Winder’s outposts near present-day Mellwood, Maryland, 12 miles southeast of Bladensburg. The British drove on the American outposts, only to discover artillery backed up by 1,200 infantry. Ross then made what many historians have called “a feint” toward the American garrison at Ft. Washington on the Potomac River, leading Winder to conclude there would either be a night assault there, or an attack on his own right flank. Thus, Winder took no offensive action during the night of August 23/24 .

Meanwhile, Stansbury and his Maryland Militiamen stayed the night at Bladensburg on the west side of the eastern branch of the Potomac River, leaving the town undefended on the opposite shore, the direction from which the British were expected to arrive the next day.

Ross, however, was as undecided as to what to do as his counterpart Winder, and again it was Cockburn who acted as the spur, urging the general to attack Washington, D. C. Finally, at Mellwood, Ross decided to head for Bladensburg, five miles off, concluding that it would be a good place to ford the river toward the capital, and the likely position of enemy forces.

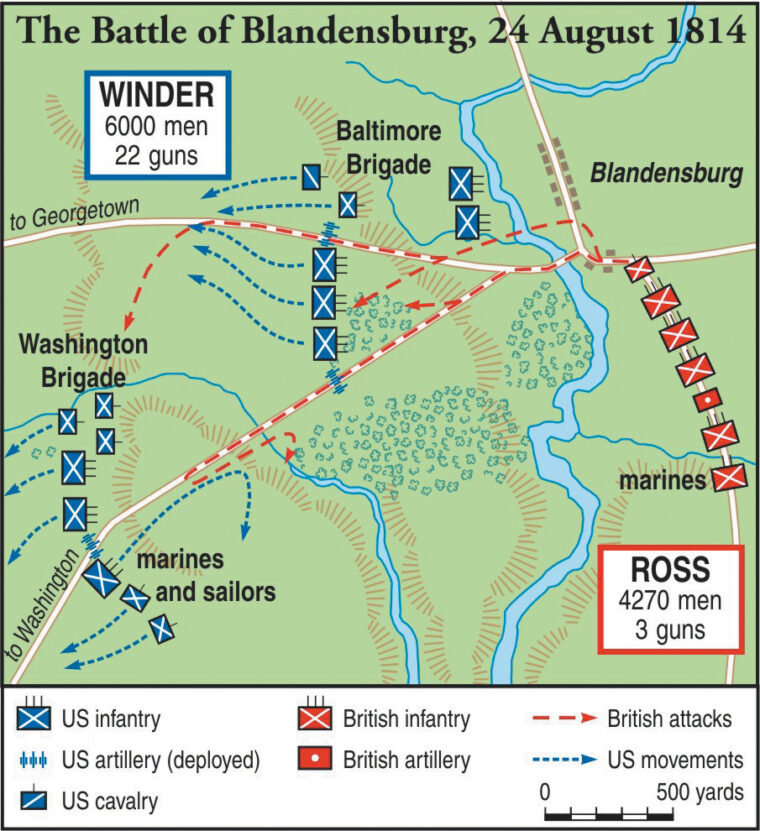

Thus, at 5 am on Wednesday, Aug. 24, the British force set off at last to capture the capital of the United States. As they marched, the heat began to rise. By 10 am, the temperature stood at a sweltering 98 degrees. The sweating British force was organized into three brigades; the 85th was leading the way, far ahead of the other two. When Ross saw the American forces drawn up at Bladensburg, he decided to attack with the 85th only—a mere 1,400 men—without waiting for the other two brigades.

In Ross’s view, the Americans had already made two critical military errors: they had given up the hill upon which he was now positioned with the lead elements of the 85th, and they had also abandoned–without a fight–the sturdy brick town itself, from which enemy snipers could’ve wreaked havoc among his men.

While Ross considered the opening phase of the Battle of Bladensburg, Cockburn—complete with gold-laced hat and epaulettes—helped set up the marine artillery and the army’s Congreve rocket launchers. He, like Ross, was to be in plain view and under fire from enemy marksman during the entire battle.

The tobacco port town of Bladensburg had been founded in 1742. The place where the British chose to launch their river crossing is now marked by the Peace Cross, a very tall stone sculpture commemorating local World War I losses.

British Army chaplain Lt. George Robert Gleig—later the Duke of Wellington’s biographer—left a good account of the scene in a book of memoirs published in 1826. As he recalled, the two main forces sighted each other at noon. Lt. Gleig was impressed with the initial American position, drawn up in three succeeding lines upon the forward slope of the hill to their front. The right flank was anchored in a wood and a deep ravine, with the left and front covered by the Anacostia River, a branch of the Potomac. The river ran between the two armies and was spanned by a single narrow bridge.

This bridge extended from Bladensburg’s main street and connected to a road running straight through the center of the American position. Ross meant to take it. The right flank of the American line had a woods, but most of the American bank of the river was completely exposed to British fire. This was where the Americans had chosen to place their skirmish lines, with strong forces of riflemen screening the frontal sections of the lines. Behind the skirmishers lay open fields, broken by criss-crossing fences.

Midway up the slope and behind one of these fence rows was the first of the main U.S. lines, made up of infantry. Behind was the second line, also of infantry. Beyond this was the third line situated in a wood, atop the heights.

Gleig judged that the Americans had 20 pieces of artillery, with four commanding the bridge and the town. The rest had been placed here and there along the second line in between the various infantry regiments, as if somehow to link them together. American cavalrymen—380 in all—were placed en masse on the left. There was no British cavalry on the field; only Ross and Cockburn were mounted.

As the British soldiers stood euphoric in the empty streets of Bladensburg, the Americans opened the battle with the first salvo of artillery, forcing the Redcoats to scatter for cover. While Ross decided whether taking the bridge was going to be worth the cost, there were fateful events occuring on the American side of the lines.

An angry Commodore Barney and his command, ordered to guard the prized Navy Yard in the capital itself, had been—unbeknownst to Winder —approaching from the Americans’ rear.

Earlier, both Winder and Madison had asked Secretary Monroe to go to Bladensburg to help General Stansbury post his men, and this he did. General Stansbury was naturally irked by “Colonel” Monroe’s advice.

The roads joining at Bladensburg consisted of the old post road running from Baltimore to the Federal City, and one to Bladensburg from nearby Georgetown, just a few yards from the bridge. It was the crossroads that made this place such a valuable piece of real estate. Once across the Anacostia, which was fordable at many points above the bridge, there was no other geographical or topographical hindrances to a rapid enemy advance on the Federal City.

General Stansbury’s force had been posted near a mill where the roads converged, about 350 yards from the bridge. An earthwork barbette had been hastily erected there, between the Federal City Road and a large barn. Within the barn were half a dozen six-pound guns along with 150 Baltimore artillerists commanded by Captain John Myers of the Virginia Militia and Colonel George Magruder of the 1st Regiment. Because the embankment was too high for the small cannons, gun ports were cut into the earth so they could fire at the bridge and both roads. Placed to the right of this battery were Pinckney’s riflemen, at the point where the roads intersected, and in a spot hidden by bushes.

Near the large barn and the Georgetown Road, 50 yards behind Pinckney’s men, was Sterrett’s Dandy 5th Regiment of Baltimore Volunteers. The Baltimore County Militia of both John Ragan and Colonel Jonathon Schutz had their right touching the left of companies commanded by Captains Robert Gorsuch, and Jeremiah Ducker, and these also looked to the Georgetown Road.

This, then, was General Stansbury’s initial deployment when, without consulting him, and in view of the enemy, Secretary Monroe decided on his own to redeploy the general’s men. Even as the enemy approached from the far side of the eastern branch of the Potomac, Monroe pulled back the Baltimore regiments of Sterrett, Ragan, and Schutz a quarter mile behind the riflemen and artillery. This must have seemed to Monroe—who had been a Colonel in the Revolution—a good way to provide these green militiamen with covering fire.

Now their right flank rested on the Federal City Road, and this second line was in complete view of the advancing enemy, completely bare of cover and within easy range of the Congreve rockets that the men were about to experience for the very first time in combat. Worse, this “second” line was too far from the first to provide effective fire support when the imminently-expected British attack came.

When Winder arrived on the battlefield it was at his direction that the third line seen by Lieutenant Gleig was posted atop the heights, about a mile from the bridge assault that would form the battle’s opening gambit. The line included the just-arrived Annapolitan regiment commanded by Colonel Beall on the far right and Barney’s just-arriving Flottilamen at the center on the Federal City Road with their twin 18-pounder guns a few yards from Rives’ barn. The left of this third line was anchored by Colonel Magruder’s District of Columbia Militia, U.S. Army Lt. Col. William Scott’s Regulars and Maj. George Peter’s artillery battery. Giving advice to Winder as he laid out his lines was attorney and member of the D.C. Militia, Francis Scott Key. Key later surrendered himself to the British in hopes of negotiating the release of Dr. Beanes.

Tournecliff’s Bridge crossed a small ravine 500 yards in front of this position to the north of which was an old dueling ground, and a small grassy glade. Above the glade was the bluff where the companies of Captain John J. Stull and Captain John Davidson were placed about 150 yards from the road.

Behind Major Peter’s battery were stationed Lt. Col. Scott’s Regulars, Major Henry Waring’s battalion of Maryland Militia and Colonel William Brent’s 2nd Regiment of Gen. Walter Smith’s 1st Columbian Brigade. Magruder’s left touched Barney’s right, with his own right on the Federal City Road. A small force attached to a Lt. Col. Kramer was just in front of Colonel Beall’s tired Annapolis Militia.

This was the situation around noon as Winder prepared to fight his first major battle with troops placed by himself, Secretary Monroe and General Stansbury. None of these groups of soldiers had ever fought together before as cohesive units, with the exception of Barney’s sailors and his attached 103 U.S. Marines under Captain Samuel Miller.

Madison and Armstrong had arrived to witness the battle in person. Indeed, upon their arrival on the field, the entire presidential party was almost captured when it rode across the bridge into Bladensburg. A clerk in the American militia yelled that the enemy was in the town, and they bolted back. Thus, but for the clerk, the war might have ended right then and there with the top officials of the U.S. government in enemy hands.

The American guns opened fire at 12:30 pm while the enemy on the far side of the Anacostia were seen to be fooling around with some odd-looking long tubes. Soon, the first barrage of Congreve rockets was let loose on a terrified and astonished American army. The U.S. infantry quaked, but their artillery drove the British to take cover behind Lowndes’ Hill to the rear of Bladensburg.

Then, regrouped, the British appeared to the Americans to be storming the bridge, and Winder’s first and second line artillery blasted it, as did Pinckney’s riflemen, tearing great holes in the Redcoat ranks, slaughtering a company of infantry in this manner as they tried to run across. At first, the Americans were cheered by the sight of running and bleeding “ Wellington’s Invincibles.” But then they could see through the thick smoke that the ranks were still advancing, and their feelings veered from elation to respect to fear. How could these men endure such a terrible pounding and still come on? Suddenly they understood why the British infantry was considered the best on Earth.

Quickly the American first line rolled back upon the second behind it. As one American company simply dropped its weapons and ran away after the first firing, the initial British brigade ignored the bridge where they had been stopped and forded the stream instead. Overjoyed to be across, they failed to await the second brigade’s arrival to support them, deciding to take the hill in front alone. They shed their heavy packs and haversacks to make the job easier.

As they crashed into the American second line, they were hit by Captain Benjamin Burch’s artillery. Spreading themselves out too thin across the American front, the brigade erred, and Winder saw it. At the lead of the Dandy 5th himself now, he sent it and Stansbury’s men to halt the British advance, and they did. This was followed up by a brief American bayonet assault that drove the Redcoats into the woods to their rear, near the bridge at the shoreline. Here the British halted, however, and waited for reinforcements from the second brigade.

When the second brigade of British arrived the Redcoats advanced upon the American left. They were turning it just when another terrifying rocket barrage crashed into the center and right of Stansbury’s position. This was too much for the men of both the Ragan and Schutz Baltimore County commands, and they broke, fleeing in terror for their lives. The panic was massive, and Winder, try as he might, could not stem the tidal wave to the rear. Sterrett’s men stood their ground until they saw they were outflanked by the British on both the left and right. Then Winder ordered their retreat back up the hill before the entire command was shattered.

Watching the rout that he was unable to stop, General Winder saw the rockets landing among his men, and soon the stationary Dandy 5th Regiment was taking fire from both the turnpike and unseen guns in an apple orchard. Pinckney was wounded in the right arm by a musket ball, and Winder ordered Sterrett to fall back further.

Then it was the Dandy 5th’s turn to break and run for cover. They had seen the rest of the army break before them and run, and now their retreat became a rout as well, a single wave of infantry, artillery, and cavalry that up to now had been hidden in their ravine.

The president blurted out, “Come General Armstrong and Colonel Monroe! Let us go and leave it to the commanding general!” With this statement Winder was to become tarred with the greatest defeat in American history until the Civil War, being almost universally blamed by all except by his fellow Baltimoreans.

Winder’s agony, however, was not yet over at Bladensburg. Trying to steer the running force toward the Federal City, from which direction he knew the Washington Militia was coming to reinforce him, Winder failed yet again, because he chose the Georgetown Road instead of the Federal City Road. Caught up in the rout were the members of the American government, who realized at last an awful fact: The standing army of the United States was not only being defeated, but was now running in full flight from the enemy, and it was only 2 pm.

In reality, Bladensburg was a trio of seperate battles—involving the first, second and third American lines, each out of any real contact with the others, and all of them out of touch with the reserves in the rear. Each fought the British in their own, separate, uncoordinated fight.

Now began the third and final phase of the contest, for the combined Barney/Miller force of sailors and marines were about to make their mark in the history of land warfare.

When the initial firing had begun, Barney and his men were still within the District’s limits, but arrived in time to be placed into position by a surprised Winder. Barney and his flotillamen took the center of the line, with U.S. Army Regulars and the District and Maryland Militias on his flanks. As he saw Ross about to engage him, the Commodore shifted a pair of his own18-pounders to sweep the dueling glade with canister shot. As British Colonel William Thornton’s men came within range, Barney gave the order to fire.

Thornton was one of the first to fall wounded, and rolled down the hill—literally—to safety. Taking over from him was Colonel Arthur Brooke. He was unable to rally the Redcoats before Barney’s sailors came plunging down the hill into their mass of swirling cutlasses and pikes, joined by the 103rd Marines wielding their bayonets, and shouting “Board ‘em! Board ‘em!” as if they were taking an enemy ship at sea.

Thus, for the second time that day an American force was treated to the delightful spectacle of seeing their foe on the run, back to the woodline. If only Winder’s other troops had stood and fought as well, and were now available to expand Barney’s dent in the enemy front, Bladensburg might have been converted into an American victory.

Barney and Miller were in the process of winning their battle—Bladensburg’s third—when Ross decided to outflank the Commodore’s position by sending his 4th Regiment in a wide arc to the rear, while simultaneously advancing both the 44th and 85th to Barney’s front and left, attacking the greatly outnumbered sailors and marines from three directions. Barney was seriously wounded by a bullet in the hip. (He never got the bullet out and it eventually killed him in Pittsburgh in 1818.) Then Barney’s men ran out of ammunition.

Barney then gave the order to retreat, even though he had to be left behind. The men withdrew toward the Federal City. But the wounded Barney had held the center of the third line longer than either Winder or the British thought he could.

By now, Ross had displaced both of the American flanks. The British swept the entire hill before them. Lieutenant Gleig took a flag dropped by a fleeing militiaman, and this became the famed “Bladensburg Standard” that still resides in the 85th Shropshire Regimental Museum in England.

Ross and Cockburn came up to accept the brave Barney’s surrender in person, and the Commodore became the ranking American prisoner-of-war. When an English naval officer introduced Barney to the Admiral as “Co-burn,” the Commodore tartly replied, “Oh, Cock-burn is what you are called hereabouts!” Then, relenting a bit, he added, “Well, Admiral, you have got hold of me at last.” A gallant man in times like this, the most hated Englishman in America replied, “Do not let us speak of that subject, Commodore! I regret to see you in this state.” Both the general and admiral agreed to parole the injured sailor to wherever he might wish to recover.

Now Ross took stock of the great victory he had just won. With only two-thirds of his own army present on the battlefield, he had routed a force over twice the size of his own, seizing 10 guns, 220 muskets, and 120 prisoners, as well as having inflicted 150 casualties. The British in turn lost 250 both killed and wounded, including 18 of its best officers, a costly victory when replacements were far away in England.

The news at home came as a shock. It had been a complete and utter rout and everyone knew it. The Norfolk Herald reported that the British “moved as steadily and as undismayed as though there were no opposition,” while the Philadelphia General Advertiser carried a letter to the editor that asserted, “Our militia were dispersed like a flock of birds assailed by a load of mustard seed shots.”

In his official report Colonel Sterrett stated dejectedly, “We were outflanked and defeated in as short a time as such an operation could well be performed,” but one of Barney’s escaped flotillamen put it into more succinct terms that all could easily understand: “The militia ran like sheep, chased by dogs.”

Ross wrote the next day of Barney, “Had half your army been composed of men such as your Commodore commanded, with the advantage you had in choosing your position, we should never have got to your city.”

According to Robert Moskin’s 1977 history The U.S. Marine Corps Story, “Despite the numbers involved, American casualties were estimated at only 10-12 killed and 40 wounded; the Marines alone had eight killed and 14 wounded.” Gleig, like Ross and Cockburn, was much impressed by the performance of the U.S. Marines and sailors, noting that the latter stood serving their guns, “Till some of them were actually bayoneted with fuses in their hands…The defeat, however, was absolute.”

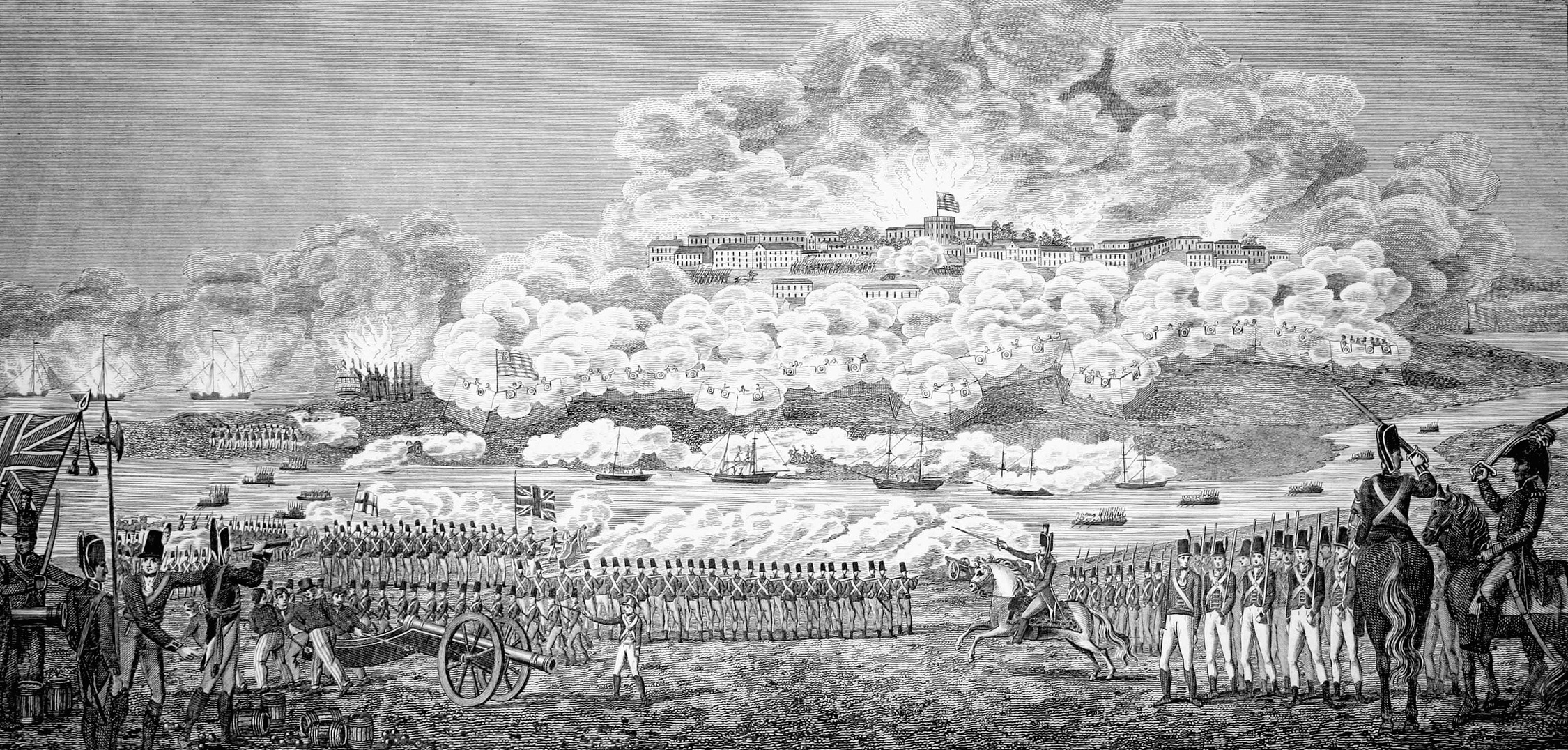

Since the shattered American army was fleeing too fast from the battlefield in order for Winder to reform it, and the Federal City was now but four miles distant, the British had it at their feet for the taking. At 8 pm that same day, as the shadows were falling, Ross and Cockburn caught their first glimpse of the Federal City as their horses trotted down Maryland Avenue from Bladensburg—today’s motorist can still ride into downtown Washington as they did directly from the battlefield.

Ross and Cockburn advanced cautiously with a party that consisted of the British 3rd Brigade, the sailors, 21st Foot and Royal Marines, and it was dark as they rode in. As they would upon entering a conquered European city, Ross had their presence announced by a roll of drums summoning the city fathers to a surrender parley. But no one responded at all.

The capital of the United States had been abandoned to the enemy, a fact that left the British incredulous. Leaving the main body of troops behind, Ross and Cockburn took 200 men and cantered on their horses brazenly to an open space before the U.S. Capitol. Here they believed themselves to be fired upon by snipers from inside the Capitol as well as from nearby houses. Ross himself had the second horse of the day shot out from under him, and—urged by Cockburn—decided to burn the capital’s public, but not private, buildings. The snipers were later believed to be some of Barney’s escaped flotillamen who ignored the flag of truce.

The British thereupon burned the Capitol, the White House, and other government buildings. Up in flames went the Library of Congress, then in the Capitol (ironically, the restored Library of Congress now holds the Cockburn papers). Ross did the best he could to protect private property, even posting guards in front of houses where they were requested. He also had a soldier flogged for stealing a Yankee goose.

One of the great issues of the War of 1812 was that of who actually burned the most cities and towns, with each side accusing the other of rampant arson. In fact, there were seven on each side. The Americans in 1813 burnt York twice and Newark once; in 1814, they torched Queenstown, Port Dover at Turkey Point, Long Point, Streets Mills and the St. Joseph Island Fort, all in Canada.

For their part, the Redcoats set fire to Havre de Grace, Md; Swanton, Vt; Plattsburgh, Buffalo, Lewiston, and Black Rock, all in New York State. In 1814, they burned the Federal City, and most likely would’ve burned other cities and towns had they the chance.

As they prepared for their departure, Gleig believed that the British—now gathered in strength on Capitol Hill—could see in the distance a “powerful army of Americans.” There was none, but even in 1826 Gleig continued to insist upon a force of 12,000 men to their front.

At home when the news arrived, the London press reacted with consternation at the deeds of their men in the enemy capital. The Statesman editorialized, “Willingly would we throw a veil over our transactions at Washington. The Cossacks spared Paris, but we spared not the capital of America.” The British Annual Register called the torching “a return to the times of barbarism.”

Still, the government of King George—previously humiliated at Yorktown—had the Tower of London’s guns fired to honor Ross’s victory. Ross was knighted Sir Robert, his immediate descendants styling themselves legally as “Ross of Bladensburg,” and a plaque was later erected in Ross’s memory at London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. An obelisk was raised to his memory in Ireland by his officers.

On the evening of the 25th, Cockburn advised Ross to march on Baltimore, up the route that is now the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, and take the city from its undefended side. Ross, however, was still worried about a rumored American army in the hinterland and decided against attacking the region’s largest city by land. Instead he retraced his steps back to Benedict and the waiting Royal Navy troop transports.

Thus “Ross of Bladensburg” threw away the military value of the victory he’d just won. From the jaws of victory, ultimate defeat was snatched for the overall campaign objective of destroying Baltimore as the center of privateer construction. In addition, an aroused American nation rallied around the Madison Administration and the war went on. The same army led by Ross was to be met at North Point, Maryland, later in the year in 1814 and at New Orleans in 1815.

This was the last time that Americans and Britons waged war against one another. As late as 1931, however, there existed in the U.S. War Department a contingency plan for war against its mother country.

Towson, Md., book author Blaine Taylor is the writer of the forthcoming 1814: In Full Glory Reflected—The British-American War on the Chesapeake Bay-Tidewater. During 1991-92, he served as a Congressional press aide on Capitol Hill, and walked the Bladensburg battlefield to craft this account.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments