By Robert Barr Smith

On the banks of the rain-swollen Shangani River, a small force of white militiamen closed ranks as hundreds of Matabele warriors swarmed around them. They intended to sell themselves dearly.

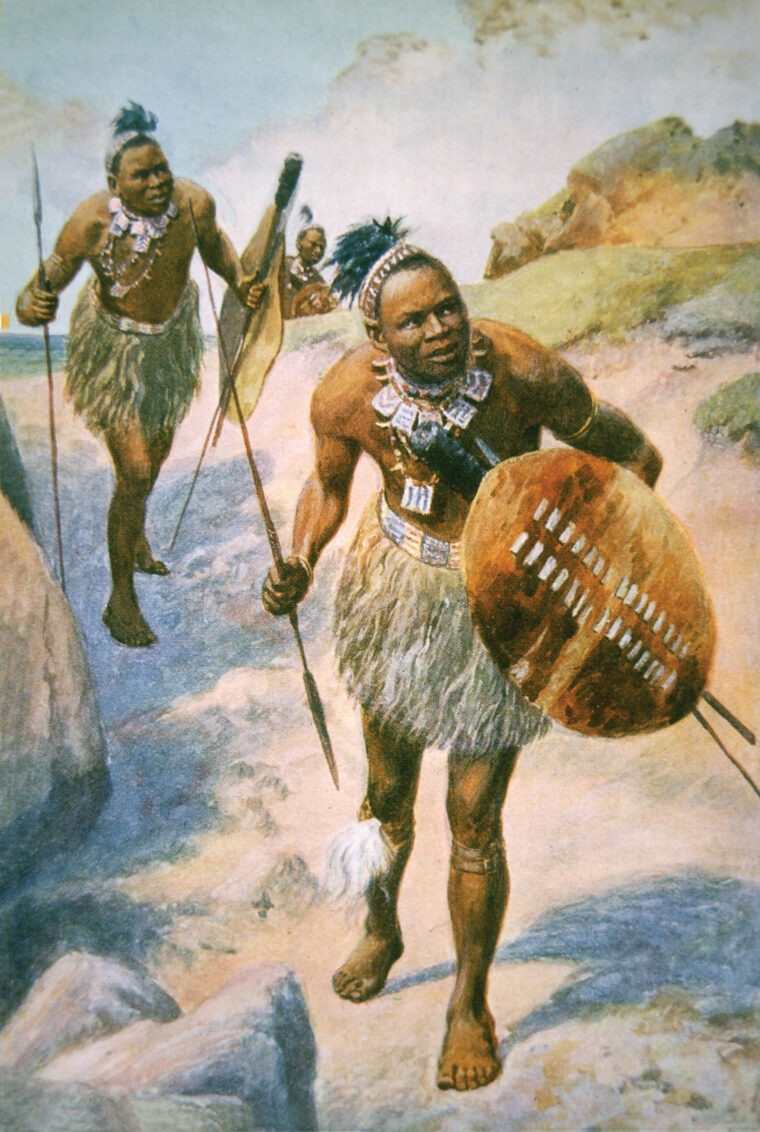

In the Matabele language there was no word for “soldier”. The Matebele did not need such a word because every Matabele male was a soldier. There was no other acceptable occupation for young tribesmen, and they had no other ambition. As the Matabele viewed the world, everyone else was merely quarry, especially their nearest neighbors, the wretched Mashona. The Matabele were mostly of Zulu stock, members of a group that had split off from Shaka Zulu’s nation about 1821 and migrated north under a war chief named Mzilikazi. Acquiring other peoples as they went, they built a new nation north across the Limpopo River from the Transvaal, retaining their fierce Zulu ways.

For a while the Matabele dominated the area around them, wetting their spears copiously and carrying off their neighbors’ women and children with impunity. But as the 19th century rolled by, things began to change in East Africa. New forces were stirring on the continent, and new and formidable people were beginning to appear on the edges of the land that the Matabele considered their private preserve. The Matabele began to encounter white men in ever increasing numbers, Britons mostly, and in the latter part of the century they would have the misfortune to find their nation in the direct path of Cecil Rhodes, the visionary, thrusting apostle of empire.

Rhodes founded the Imperial British East Africa Company in 1888, partly to block German encroachment into East Africa. In this he succeeded, opening thousands of square miles to British farming and mining. Over time a series of concessions by the Matabele opened up more and more land to the newcomers. The men who began to push into the new territory were hardy, ambitious, and eager to prosper. They were not the sort of adventurers to be deterred by native armies, no matter how large and well-trained they were.

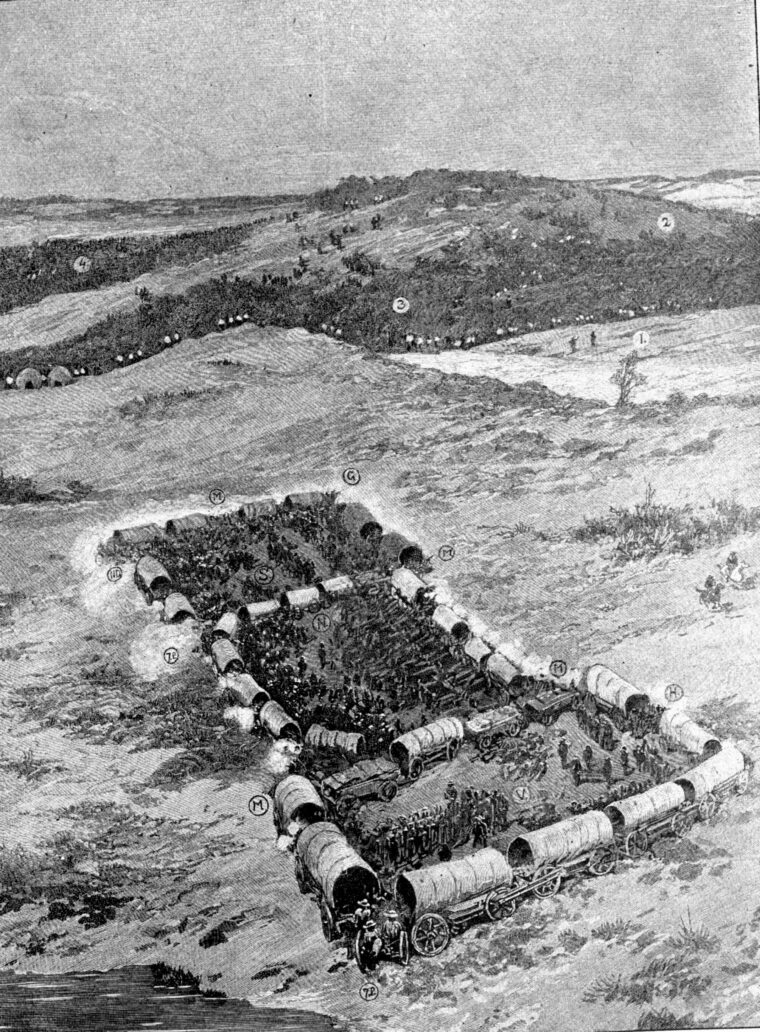

The first major incursion into Matabele territory was the Pioneer Column, sponsored by Rhodes’s company, which moved into Mashonaland in 1890. Half of the 400 white men in the column were prospective settlers. They came to stay, complete with wagons, servants, and livestock. The other half comprised Rhodes’s company police, a well-armed paramilitary force alert and ready to fight anyone who threatened the column. They brought with them a pair of 7-pounder guns and four machine guns—two Maxims, a Nordenfeldt, and a Gatling. The individual weapons of choice for the newcomers were the rugged Martini-Henry rifle and the Webley .45-caliber revolver. The column was organized along military lines, since the company expected that there might be attacks by the Matabele. Out in front rode a scouting element led by famed big-game hunter Frederick C. Selous. The column’s night laagers (camps) were covered by a 10,000-candle-power searchlight with its own generator, a brilliant sun in the darkness that must have astonished the Matabele.

Matabele King Lobengula and the white men worked out a boundary between his home territory and the area settled by the British. This arrangement cut the Matabele off from their favorite raiding areas, however, and made the young warriors especially restless and resentful. The white men were between them and their traditional rite of passage into manhood—the washing of their spears. Lobengula’s tribal rivals began to conspire against him. Trouble was on the way. It came in 1892, when somebody cut out some 500 yards of newly completed telegraph line between Salisbury and Cape Town, South Africa. The cutting was probably done by the Mashona. They had nothing against the line, but the chunks of wire cut from the poles were fine raw material for bracelets and other decorations.

The company protested to Lobengula, as general overseer of the area, and he promised to deal with the problem. The wire-cutting did not stop, however, and in time a further dispute arose over the number of cattle given in payment for the wire-cutting or seized by the company in retribution. The incident was also smoothed over, and the uneasy peace continued. But then a small Matabele force began raiding native villages within 10 miles of Fort Victoria. The foray was allegedly made to punish the villages for the theft of some Matabele cattle. A small force of whites pursued and scattered the impi (raiding party), and quiet returned—for the moment.

Real trouble arrived in July 1893, when an arrogant warrior leader defied Lobengula’s peace and permitted his impi to ravage native villages close to the area settled by the whites. Some of the raiders pursued terrified villagers into the white settlements and even speared their wretched quarry in the streets of Victoria. The night horizon flickered and glowed as Mashona kraals burned in all directions. Panicked Mashona refugees ran for the safety of the white areas, where they were given shelter. Many less lucky Mashona were killed or kidnapped, and one British clergyman spoke for most of the colonists when he wrote that it was “a sickening sight to see the number of human beings lying dead on all sides, mutilated by the Matabele. No Christian people can simply fold their hands and allow hundreds of their fellow creatures to be murdered wholesale.”

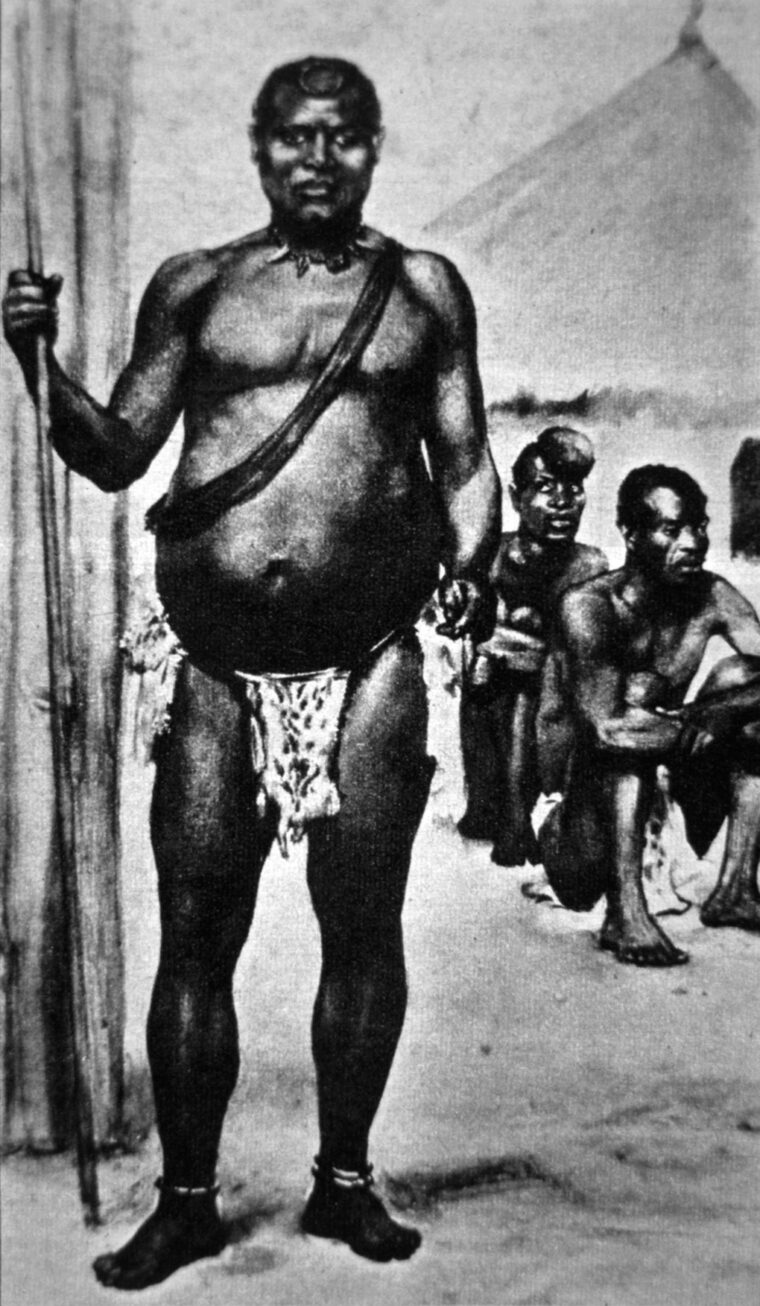

Maria Colenbrander, a half-Dutch, half-English friend of Lobengula’s, tried to preserve the peace. She warned the king that if he made war the English would attack him in his own town. “What does a woman know of such things?” Lobengula told her. “You have never seen my armies in battle. These white men will only make breakfast for them.” “You have not stood up to Englishmen in battle,” she replied. “You have spent your life beating out the brains of children and ripping the bellies of old women. Keep your baby-killers in check, King, or they will drag you to your ruin and your country will belong to others.”

The warning went unheeded, however, perhaps because it had come from a woman, or perhaps because things had gone so far that there was no turning back. In any case, Lobengula began to issue rifles—many of them modern Martinis—from the royal armory and move his regiments into striking position. Company police and volunteer units such as the Victoria Rangers gathered, and the Cape Colony’s Bechuanaland Border Police were put on alert. Short of horses, the British sent agents into the Transvaal to buy more. Nobody but the restless young Matabele warriors really wanted war, but the affair had already gone far beyond talking. No amount of words was going to change their warlike ways.

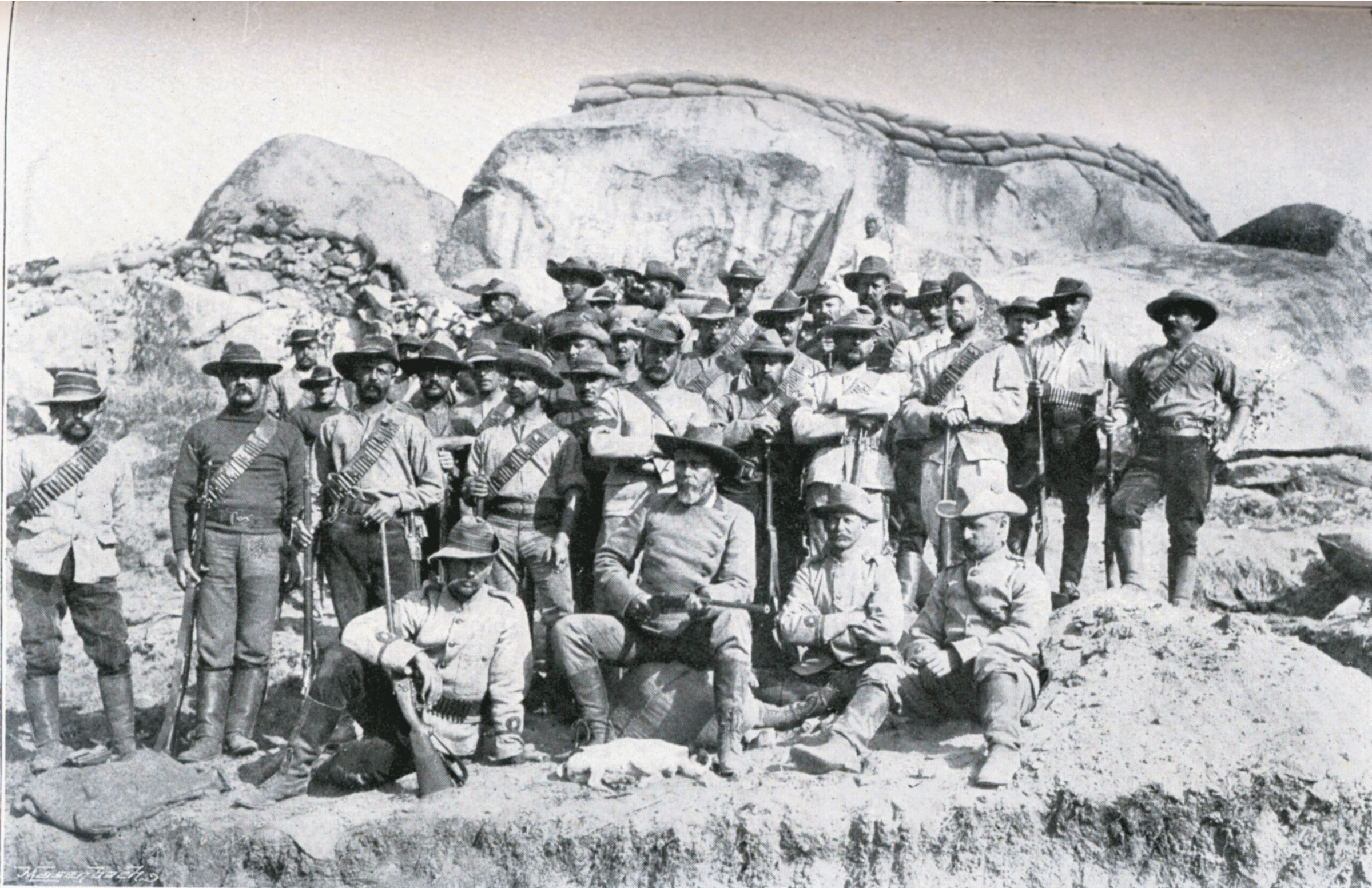

If the Matabele had numbers on their side, the British had both the firepower and the courage to match the dogged bravery of the tribesmen. The whites were mostly local men, volunteers from among the settlers. They were mainly farmers, ranchers, and miners, although some were hunters like Frederick Selous. A few were simply adventurers, like American Frederick Russel Burnham, who had served as a scout in campaigns against the Plains Indians in his own country. The volunteers were augmented by members of Rhodes’s company police and local militia units. Most of these men were British, but some were Dutch and French Huguenot South Africans, mixed with a few men of other nationalities. Many had been soldiers in other times and places and had fought against other African tribes, in particular the Matabeles’ formidable, disciplined cousins, the Zulus. Most were first-class riflemen, horsemen and trackers, and their leaders, as a rule, were able and daring. They were tough, they took to discipline easily, and they could live rough and move quickly. They worked for nothing more than the promise of substantial land grants, the right to stake 20 gold claims, and a share of such cattle and other loot as might be taken from the Matabele.

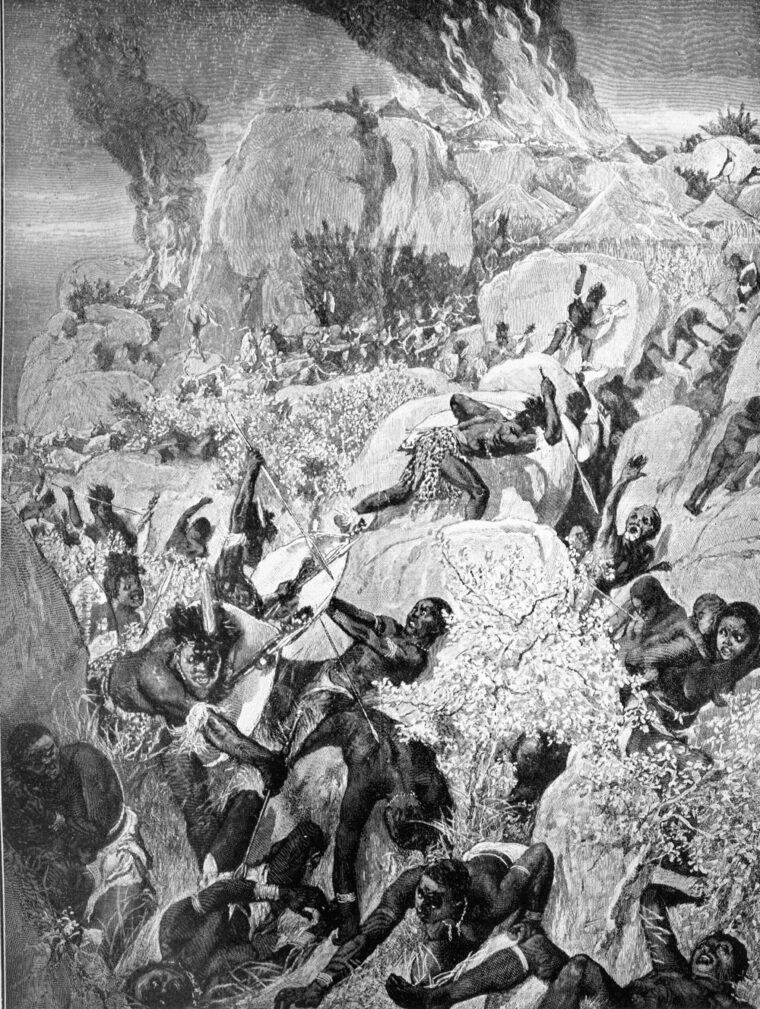

Early in the morning of October 25, 1893, several Matabele regiments, about 3,500 men, charged the night laager of a British column at a place called Bonko. The attack had been planned to take place in the bright moonlight the night before, but the British had fired three signal rockets that spouted 28 white stars and seemed to be bringing down the heavens. That terrifying sight had moved the induna (experienced leader) in command to postpone the attack until daylight. When daylight came, the Matabele came in swiftly, only to run head-on into accurate rifle fire and the fire of seven machine guns and a light field piece. By full daylight, the Matabele had lost nearly 600 men and failed to close with their enemy. British losses did not exceed 60, and most of these were allied Mashona tribesmen.

The defeat astonished the Matabele—it was a catastrophe entirely beyond their experience. Not only had they suffered terrible casualties, but they had failed even to come to grips with their enemy. Once the fighting was over and the battlefield cleared, the British column saddled up and marched into Matabele territory. For all their courage, the Matabeles’ confidence was shaken. Subsequent fighting did not improve their morale. The enemy artillery confounded them—the warriors did not understand the difference between the report of the piece and the explosion of the round it fired. In a letter home, one volunteer put it this way: “The latter gun did tremendous damage, killing them by fifties. They couldn’t make it out at first as they saw the smoke miles off and heard the report and presently another report in the middle of them and dead and dying all round. They call it the ‘bye ‘n bye’ gun and at first it was amusing to see them fire volley after volley at the shell directly as it dropped thinking if they hit it they might kill it.”

The decisive battle of the war came at a place called Egodade, where King Lobengula’s big impi—some 6,000 warriors—attacked the British column as it halted at midday. This time, at least a third of them carried rifles in addition to their traditional weapons. There were a few Winchesters among the warriors’ weapons, and about half of the Matabele firearms were modern Martini-Henrys, the accurate big-bore service rifle that until recently had been the standard arm in the British Army. In both fighting men and rifle strength, Lobengula’s men far outnumbered the British force, which was fewer than 700 strong.

The British marched in two parallel columns 200 yards apart. About 20 wagons and long ox teams moved in each column, flanked by some 400 mounted troopers. Between the lines of wagons flowed a river of oxen, thousands of them, driven by native herdsmen. The waiting Matabele watched as the column went into camp in two separate laagers about 100 yards apart, on either side of a small native kraal. The white men dismounted and began to cook their mid-day meal, sending their oxen and most of their horses to water and graze at a place almost a mile away. It seemed a heaven-sent chance to the Matabele, a chance to strike hard while the Englishmen dozed. But the Englishmen were not dozing.

The impi first learned that their foe was alert when one regiment appeared on some high ground about 2,500 yards from the British. British gunners began to lob 7-pound cannon shells into the Matabele ranks. The warriors abandoned the exposed ground and found cover in the rolling grassland below, but the regiments kept coming. By now the British had succeeded in driving their horses and oxen back into their laagers, and their buglers called the outposts back to the safety of the main body. The British no longer wondered where Lobengula’s main force was, if indeed they had ever lost track of it. The impi was coming toward them across the veldt—long, disciplined waves of warriors flashing spear points above ox-hide shields.

Contrary to their long-cherished battle drill, at Egodade the Matabele advanced more slowly than usual, perhaps to allow their riflemen to fire into the British wagon laager. Then small groups of warriors rushed the British perimeter, only to melt away before the white men’s steady rifle fire and the lethal hail of their machine guns. The Matabele went down in heaps, leaving piles of dead in the wake of their advance. All their valor achieved nothing. Under the unceasing British fire, their disciplined formation began to unravel until they were fighting in bunches, coming on “in the shape of a lot of locusts,” as one English soldier put it. By about two in the afternoon it was all over. Matabele casualties were somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000, and once again British losses had been negligible.

For years afterward the bones and skulls of Lobengula’s warriors littered the rolling grassy veldt where the Matabele had fought so bravely. Their swift retreat left them no time to pick up the shields and spears of the dead. Once again the regiments had failed to come to grips with the enemy. Their own rifle fire had been largely ineffective. It seemed that nothing could stop the steady, methodical advance of the white men, covered by the terrible fire of the Maxim guns and little cannon. The Matabele could kill a few of the whites at immense cost to themselves, but it was obvious that there was no halting the implacable enemy. In time, hunger and misery and heavy casualties would force the Matabele nation to surrender.

Lobengula saw the inevitable end clearly. He loaded his wives and treasure into wagons and began to move his household north from his capital at Bulawayo, preparing to leave his kingdom entirely. Along the way he received a letter from Rhodes’s chief executive officer, Dr. Leander Starr Jameson, written in English, Dutch, and Zulu, promising kind treatment in return for his surrender. Lobengula did not surrender, and a column was organized to search for him and bring him in. It numbered just over 300 men, plus native bearers and three Maxim guns, all under the command of an experienced major named Patrick Forbes.

Forbes’s men trekked through desolate territory, past a destroyed missionary station, into a country largely denuded of provisions. The major reduced his column to about 160 men and pressed on through a sodden, dreary landscape inundated by heavy rains. The going was difficult for both pursuer and pursued, and food was hard to come by. Forbes’s men were on three-quarters rations and their horses were exhausted. They had abandoned their wagons when the oxen could no longer pull them through the morass. Ahead of the British advance, many of Lobengula’s men simply went home. Some who were sick or wounded drifted away to die in the bush. By the time the king’s entourage reached the banks of the Shangani River, Lobengula was tired and discouraged and suffering from an acute case of gout. Although many of his men had gone home, three of his best regiments were still with him.

Once across the river, the king halted on the north bank of the Shangani, and his men threw up scherms, or cattle enclosures, and constructed wooden fences around Lobengula’s wagons. The king took counsel with his indunas, many of whom felt that further fighting was futile. Too many warriors had been killed already. Lobengula decided to end the war—he would surrender and negotiate the best peace he could.

Now the real tragedy began. Lobengula had written a second letter to Jameson, offering peace, and sent along a bag of gold sovereigns to demonstrate his sincerity. The letter and coins were entrusted to two dependable messengers, who set off to deliver them. The messengers came across two troopers named Daniel and Wilson, who were stragglers from the search column. The two renegade troopers kept the gold and threw away the letter that might have ended the war. They told nobody of Lobengula’s offer, not even their own officers, and the last, best chance of peace went glimmering. The stage was set for one last battle in Matabeleland, a storied fight that would do great credit to both sides in the sad little war.

Forbes and his men were marching into great danger, and Forbes knew it. All around him, on the south side of the river, were Matabele units, perhaps as many as 3,000 warriors altogether. On the afternoon of December 3, Forbes pulled his column into a defensive perimeter on the banks of the Shangani, a couple of hundred yards back from its bank. Forbes knew that the heart and soul of the Matabele nation was its king. For all the dissension within the tribe, the ordinary warriors revered their sovereign and would cheerfully die for him. The British commander knew that the king’s capture or death might well put an end to the war. Accordingly, in spite of the danger, he decided to try to capture the fleeing king.

Forbes correctly reasoned that Lobengula had crossed the Shangani toward the north. He also believed—incorrectly, as it turned out—that the king had no more than a hundred fighting-men around him. Forbes sent a little column splashing across the rising Shangani in a drifting rain, a tiny force of 15 troopers under Major Allan Wilson, an experienced, daring officer who spoke Zulu fluently and was an expert tracker. Forbes’s decision was probably wrong in hindsight, although his reasons for splitting his little force in the face of the enemy seemed sound at the time. If he took his whole force across the river, he would have the rising Shangani at his back, cutting off all chance of retreat and leaving several thousand Matabele in his rear. Nor did he order Wilson back across the rising river when it became apparent that Matabele thronged the north bank as well. If anybody could bring in the king, he thought, Wilson was the man. Forbes temporized, reinforcing Wilson to a total strength of 32 men, but sending him no machine guns.

Wilson was a tall, handsome officer with a thick mustache, popular with everybody who knew him. He was the sort of man who was the life of noisy drinking parties in the mostly male frontier world, even though he touched nothing more potent than ginger ale himself. He was a good leader, easy-going and calm. Riding with the raiders were two Americans, Pearl Ingram and Frank Burnham, a storied soldier of fortune. Once they crossed the Shangani, Wilson’s men began to encounter more and more Matabele. Night was falling, and dozens of cooking fires began to flicker in the gloom. Wilson realized that his tiny column was in the middle of a huge host of Matabele that outnumbered him many times. Still he pushed on, calling out to the startled warriors, “Put down your guns! The war is over! We want your king to meet our induna. Where is your king?” All around the column in the darkness Wilson’s men could hear movement and the cocking of rifles, but nobody fired.

At last one young warrior pointed in the direction of Lobengula’s camp, and Wilson called to him, “Run on; we will follow you.” He said softly to Burnham, “If he misleads us, shoot him.” But the warrior took Wilson straight to Lobengula’s wagons, drawn up in an open glade and enclosed by a little stockade of hard mapami wood. At every step they heard more gunlocks snicking around them in the night, but still nobody fired. Behind them masses of warriors gathered in the gloom, and Wilson’s troopers could hear much movement and shouting in the bushes and trees. The pitch-black night flashed and flickered with lightning and thunder grumbled in the distance. “The king is here,” said their guide, but he was not. The wagons and the little stockade were silent, and there were no fires. Wilson tried calling out to Lobengula, using the king’s honorific titles, but there was no answer, only the shuffling movement of many men around the tiny column. Wilson took his own men deep into the trees. By now it was so dark that Burnham carried a white handkerchief as a marker to the men following behind him.

The column kept moving until they reached an open glade, where they halted near a huge anthill to take counsel. As the rain fell harder, the men moved under the fringe of the surrounding trees. They could sense death all around them in the blackness of the night. Wilson called his officers together, and they talked in urgent, low voices in the gloom. He still wanted to bring Lobengula in peacefully, if possible. If not, his orders were to watch him until Forbes crossed the river with the rest of the column and the machine guns. Wilson sent Captain William Napier and two troopers off to cross the swollen river in the darkness and urge Forbes to come quickly and bring the Maxim guns.

One of the troopers pulled off his boot and felt across the sodden ground with his bare foot. After he found the track of Lobengula’s wagon, he and the others, leading their horses, fell back toward the crossing. At the river, the trio remounted and thrashed their way on horseback across the swollen stream. Wilson could have led his whole patrol back across the Shangani the same way. He was a good soldier and had no illusions about the odds against him, but he also knew the devastating power of the machine gun, and he may have thought that with the guns and Forbes’s whole column they could defeat Lobengula’s remaining warriors. Moreover, three of Wilson’s men had gone missing in the gloom, and he would not abandon them.

Wilson took the patrol back toward Lobengula’s stockade. Burnham led the way, feeling with his hands for horseshoe prints in the damp ground. Wilson followed, leading both their horses and commenting coolly, “I want to see how you Yankees work.” Deep in the night, Wilson found his lost troopers, and the patrol settled down near the giant anthill to snatch what sleep they could in the rain. In a short while Wilson awakened Burnham, telling him that he had heard something in the blackness. Burnham heard it, too—the soft sound of many barefoot men moving in the night. The men were moving south, toward the river, where they would be squarely between the patrol and Forbes.

Just before dawn, Burnham heard horsemen in the darkness and called out. He was answered in English. But this was not the relief column they had waited for. It was just another 22 men, and they had no machine guns with them. With daylight not far away, Burnham wrote later, “All of us who had ridden through the great camps and spent the night in the bush knew that the end had come.” Wilson called his officers together and asked what they thought the best move was. “There is no best move,” said Captain Kirton. Captain Fitzgerald agreed: “We are in a hell of a fix. There is only one thing to do—cut our way out.” Captain Borrow concurred: “We came in through a big regiment. Let’s do as Fitzgerald says, though none of us will ever get through.”

The experienced Wilson had no illusions, either. The column would never reach the river, but they might as well do as much damage to the enemy as they could before they died. The column would try to find Lobengula, the king’s royal bodyguard, and his indunas. “If we don’t get him,” said Wilson, “at least we will try to kill his leaders and save our men in Bulawayo.” The patrol moved out toward Lobengula’s stockade in the wan first light of a dreary morning and found lines of warriors already there. The British column rode silently and calmly through the Matabele, until they faced the stockade. There Wilson again called for Lobengula to surrender and again there was only silence.

Suddenly, a Matabele induna shouted, “We are here to fight!” and fired on the patrol. At that, all hell broke loose. Hundreds of rifles opened fire on the patrol from all sides, and warriors began to run toward the troopers, stabbing spears poised in their hands. One huge induna ran toward Burnham, shouting to other warriors “Buya Quasi! (Come and stab!)” The induna shot and missed. As he raised his stabbing spear, Burnham fired his Martini one-handed, and the big .450-caliber bullet mortally wounded the Matabele leader.

Wilson had no recourse but to fall back. Although his men miraculously suffered no casualties in the first firing, two horses were down, and a trooper named Dillon ran in to cut loose the saddle pockets filled with rifle-ammunition. They would need every round. Firing steadily, Wilson’s men fell back to the great anthill, some 20 feet high. It was wide enough to give some shelter to the horses and as good a place as any to make a stand.

All around them guns flamed and crashed from the forest. As one patrol member put it, “A thousand rifles and muzzle-loaders cut loose at us wildly from the timber.” He did not exaggerate. Even as men began to fall from this hail of bullets, Wilson and his troopers kept calm. When one slug knocked Burnham’s rifle from his hand, a British officer handed it back to him with a smile: “Burnham, I think you lost something.” Wilson climbed to the top of the anthill, where he stood directing his men. “Don’t waste your shots,” he called. “Pick your man.”

Dozens of Matabele went down before their rifle fire, but Wilson and his men could not stay where they were. He gave the order to fall back, and the patrol withdrew toward the open glade where they had spent part of the previous night. Even then Wilson might have led his men on a hell-for-leather gallop for the Shangani, and some of them might have gotten through, but that would have meant abandoning his wounded—something Wilson would never do. As Trooper Ingram put it, “Some of the best mounts might have got away, but—well, they were not the sort of men to leave their chums. No, I guess they fought it right out where they stood.”

Wilson sent Burnham, Ingram, and a trooper named Gooding galloping back to the river in search of help. The mission looked suicidal, but in any case death was all around them in the darkness, and the three men plunged back toward the Shangani. They pushed their tired horses through thick scrub, pursued by hundreds of warriors, but they had found a thin spot in the Matabele lines. By doubling back over their tracks, they managed to lose their pursuers. Behind them they heard a roar of firing from the glade where Wilson had chosen to make his stand. Up ahead, across the Shangani, came the unmistakable hammer of Maxim guns—Forbes was also under attack. Burnham and his companions pushed their sagging horses into the river and thrashed their way across against the flood, finally reaching the south bank far downstream. They pushed on to join Forbes, kicking their mounts through a scattering of Matabele rifle fire.

Across the Shangani, Wilson’s men fought on, 33 against 1,000 or more. As their horses were shot down, the troopers took cover behind them. One of the men, as the Matabele told the story, never took cover, but remained on his feet throughout the fight. This was almost certainly Wilson, standing up to see his enemies’ movements better. A hail of bullets poured into the circle of British troopers from all directions, and one by one they died. However carefully the British might hoard their ammunition, they had begun the day with no more than 100 rounds apiece for their rifles and perhaps 20 revolver bullets. They had found some ammunition at Lobengula’s stockade, but it could not have been much, and it might not have fit their weapons. For a while, though, Wilson’s men held the Matabele at bay, and the roar of firing could be heard across the swollen Shangani by Forbes’s embattled men. “We fought from sunrise until mid-day,” said one Matabele. “All the white party were killed with their horses, and a great number of the Matabele perished in the same battle.”

Wilson’s tiny force died hard. As men fell one by one, the survivors kept up their careful fire, some of the wounded loading Martinis for the men still on their feet. They beat off rush after rush, but as each Matabele charge receded, there were fewer men left to keep up the fire. It was not long until the rifle cartridges began to run out. As the ammunition for the Martinis ebbed away, the survivors fought on with their revolvers, until at last just seven men remained alive. These few, according to Matabele legend, stood up together, took off their hats, and sang “God Save The Queen,”—or maybe it was a hymn. The troopers then shook hands with one another and waited in silence. A final rush of Matabele closed over what was left of the patrol, and the seven died under a rain of spears. A few prayed at the end, one Matabele said, or covered their eyes with their hands. Wilson was the last to die, firing from the anthill with a revolver in each hand. Fighting on single-handed, he killed several warriors and then went down with a bullet in the hip, still firing as a rush of warriors closed over him.

Soon it was over. Lobengula’s men had killed without mercy, but they were deeply impressed by the courage of Wilson’s men. This was the sort of fighting spirit they understood. As a gesture of respect, the warriors treated the bodies of the British as they treated their own dead. All of the fallen, black and white, were left where they fell, stripped and covered with branches and stones. The Matabele, for their part, had lost some 300 of their warriors. Wilson’s men had sold their lives dearly indeed. The Matabele were struck by the fact that many of Wilson’s troopers looked very young. Standing over the bodies of their foes, one warrior said, “These are but boys. If umfaans (children) can fight like this, what will we do when the bearded men come to avenge them?”

Certain that their good-faith peace offer had been rejected, some of the Matabele moved west down the Shangani and then turned north toward the far Zambezi, trying to skirt the tse-tse fly-infested forest, and headed for Malawi. Harried by large numbers of Matabele, Forbes’s own column turned back, their rations almost gone, malaria running rampant among them. During their long retreat, Lobengula’s exhausted followers were decimated by smallpox and malaria, and in mid-January of 1894, Lobengula died. The cause was probably smallpox, but some Matabele believed that he committed suicide. Lobengula lies today on the rim of the great valley of the Zambezi. His grave is a national monument.

Later in the year, a British trader visited the place where the battle had taken place and buried the remains of Wilson’s patrol. Near the grave was a large Mopani tree, and the trader carved a large cross deep in the bark, along with the simple legend, “To Brave Men.” A bit of Rhodesian doggerel commemorated the last stand of the Wilson patrol: “With horses in a circle, they sang ‘God Save The Queen’/And 34 young troopers would never more be seen /They killed 10 times their number, they’re on the Honour Roll/So take your hat off slowly, to the Shangani Patrol.”

A more personal and enduring compliment came from Cecil Rhodes, who directed that the remains of the Shangani patrol be interred near his own planned gravesite on a rise in the Matopo Hills. There a fine monument of stone and bronze watches over them all. But perhaps the best accolade came from the Matabele warriors themselves, brave, ferocious fighting men who knew all there was to know about courage. “We lost many more than the number of white men,” one warrior said admiringly, “for they were men indeed.”

Good