By Vince Hawkins

The evening of June 18, 1757, found the remnants of Frederick the Great’s Prussian army in full flight toward the Kaiser-Strasse (Imperial Road) in Bohemia. Behind them, on the plain of Kolin, they had left over 40 percent of the army. The battle at Kolin had been a disaster. The Prussians had lost 13,376 men, and of these 9,702 were killed or taken prisoner. Some 12,307 of the casualties were infantry, representing 65 percent of that arm’s effective strength. Of Frederick’s generals, one was dead and another about to die, two were wounded, and another two prisoners. By comparison, Austrian casualties were 8,114.

The battle completely lost, and his shattered army fleeing the field, Frederick had turned over command to Prince Moritz of Anhalt-Dessau with orders to bring what was left of the army to Leitmeritz, and then departed the field with a small cavalry escort. He halted briefly at Nimburg where he sat on a wooden water pipe, “gazing fixedly at the ground, and describing circles with his stick in the dust.”

A few months earlier, the future of the war looked very bright indeed for Prussia. On April 18 Frederick had launched a surprise offensive into Bohemia. Advancing along a 130-mile front, the four columns of his army had caught the Austrians completely unprepared. By May 6 Frederick had defeated the main Austrian army under Prince Charles of Lorraine at Prague and had invested the city, trapping 46,000 Austrian soldiers inside. If Prince Charles could not withstand the Prussian siege and was forced to surrender, the way to Vienna would be open and Frederick could dictate his terms for surrender at the Imperial Palace itself. Kolin had changed all that. The Bohemian offensive was, for the moment at least, suspended, and it was Frederick who was now forced on the defensive.

After Nimburg, Frederick rode straight back to his headquarters at Prague, which he reached on June 19. An officer who saw him arrive stated, “The king had imagined himself as the conqueror of the world just a few days before, but on his arrival he presented a pitiable sight, bowed down under his pain and distress. He had been riding the same horse for 36 hours on end, and although it was obvious that he could scarcely stand, he tried to bear himself well. After he arrived he called Prince Henry to him. The king was lying on a sack of straw which had been set on a bed, since his baggage had not yet come. The king kissed his brother gently, for perhaps the first time in his life. He admitted that he was in almost mortal pain, and assured him that everything he had tried to do up till then had been only from love of his family. He said over and over again that he wished to die, and that he would take his own life.”

The only positive aspect to come out of Kolin was that Frederick had found the man he believed could revitalize the Prussian cavalry: He promoted Colonel Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz of the Rochow Cuirassiers to major general. Events were to prove this a fortuitous decision.

“The Prussian Army had hitherto been unbeatable. Now that it was hit by such an unexpected blow, that even the part which had not been involved in the defeat was overtaken by a degree of demoralization…,” wrote a contemporary. Frederick had lost his one great opportunity to take Austria out of the war. On June 20 he hastily raised the siege of Prague and moved his army back, allowing the Austrian commanders Field Marshal Leopold Daun and Prince Charles to unite their forces into a single army of a hundred thousand men.

Frederick then divided his army into two parts, each of roughly 34,000 men, and gave command of one to his brother, Prince August Wilhelm, with orders to hold off the main Austrian army. Frederick, with the other half of the army, slowly fell back down the Elba. The Austrians promptly attacked August Wilhelm and drove his disorganized army out of Bohemia and into eastern Saxony, capturing the important Prussian supply magazine at Zittau on June 23. On hearing the news Frederick became enraged and ordered his brother never to appear before him again. The prince departed the meeting in tears, a broken, disheartened man. Frederick never allowed him to command another army, and Wilhelm died in June of 1758 of a cerebral hemorrhage. On June 28 Frederick received more unfortunate news when he was informed of the death of his beloved mother, Queen Sophia Dorothea, an event that left him greatly distraught.

In Late June 55,000 Russian Soldiers Invaded East Prussia

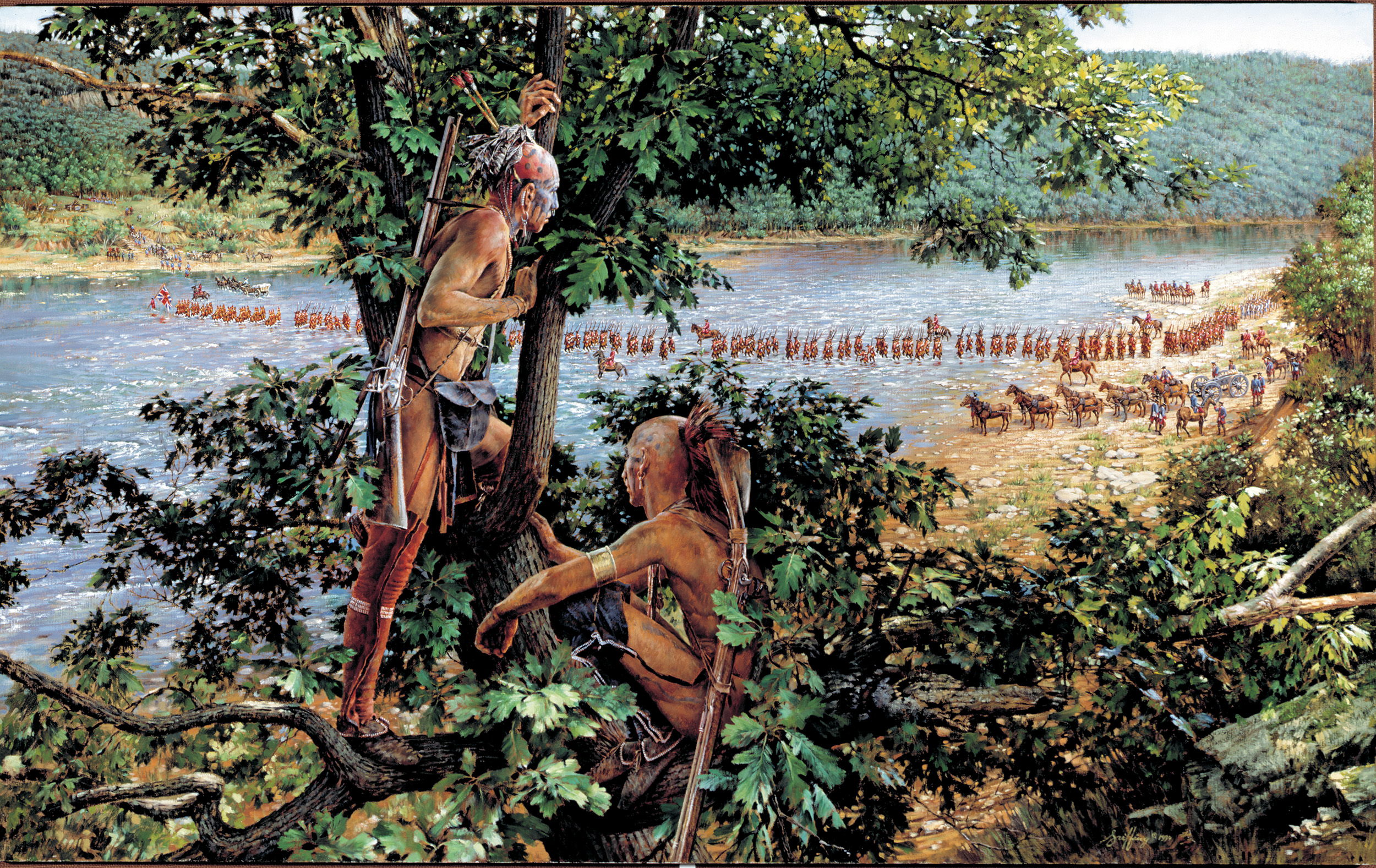

But that was not the end of the bad news, as misfortunes began to fall on Frederick like rain. At the end of June, a Russian army of 55,000 men under the command of Field Marshal S.F. Apraksin invaded East Prussia. By July 5, Apraksin had taken the port of Memel and was advancing on the capital at Koenigsberg. All that stood in his way was the 73-year-old Prussian Field Marshal Hans von Lehwaldt and his corps of 24,700 men. Lehwaldt took up a blocking position at Gross-Jaegersdorf, and on August 30 Apraksin attacked him there. The battle was a confused, bloody affair and Lehwaldt eventually withdrew his damaged corps with a loss of 4,520 men. The Russians, however, did not pursue. Apraksin’s army had also taken quite a beating. He had lost 5,989 men, and his supply system was in a shambles. Further, he knew that the Tsarina Elizabeth was deathly ill and he was waiting for news of the political situation in St. Petersburg. He subsequently pulled his army back into Poland. Lehwaldt re-formed his corps and marched west to Pomerania to meet the Swedes, who had finally gotten into the war and were moving against Stettin.

Then came the news that most of the states in southern and western Germany had declared a Reichsexekution (Imperial Edict of execution) against Frederick as a disrupter of the peace, and had begun to assemble a Reichsarmee (Imperial Army) to join the fight against Prussia. These states, some 231 in number, raised a force of nearly 11,000 men for the allied cause. French forces were also on the move and had crossed the Rhine. One French army had attacked and beaten the Hanoverian and Protestant German forces of Frederick’s only ally, Britain, at Hastenbeck on July 26. The French then drove this army back against the lower Elba, finally forcing it to surrender at Kloster-Zeven. In August, a second French army, under the command of Marshal Charles de Rohan, Prince of Soubise, had moved from Strasbourg, effected a juncture with the Reichsarmee under the command of Prince Joseph Friedrich von Sachsen-Hildburghausen, and was now advancing against Brandenburg.

Frederick’s immediate concerns were for the main Austrian army, which had taken up a very strong defensive position on the Eckartsberg ridge near Zittau in Upper Lusatia. Unable to bring them to battle on ground more favorable to his army and finally persuaded by his brother, Prince Henry, not to waste more Prussian lives by attacking such a formidable position, Frederick decided on a dangerous gamble. For the second time in two months he divided his army. On August 25, leaving Lt. Gen. August Wilhelm, Duke of Brunswick-Bevern, with 41,000 men to watch the Austrians, Frederick took command of the troops left at Leitmeritz after the battle of Kolin and advanced against the French and Imperial Army in southern Germany.

Because Prussia’s fortunes had drastically changed, Frederick had no other option but to take such risks. A few short months earlier, Frederick had stood within a hair’s breadth of knocking Austria out of the war and becoming the undisputed master of Saxony and Bohemia. Now, faced on every side with the armies of the coalition, his army significantly reduced by repeated disasters, he was forced to spread out his remaining forces and operate on interior lines to try and preserve his own territory from enemy conquest. “In this sad situation,” he wrote, “nothing is left for me but trying the last extremity … and if we cannot conquer, we must all of us have ourselves killed.” To further frustrate his efforts, it was fast becoming evident that the Prussian troops, without the dynamic presence of the king at their head, were not fighting as well as they should under Frederick’s subordinate commanders.

On September 7 an Austrian force of 28,000 attacked one such Prussian detachment at Moys that was guarding Frederick’s communications between Saxony and Silesia. The Prussian force, some 13,300 men under the command of Lt. Gen. Hans Karl von Winterfeldt, who was still recovering from a wound received at Prague, was surprised, overwhelmed, and scattered. Winterfeldt was found dead on the field, shot in the back, purportedly by some of the Catholic troops under his command. Frederick was crushed at the news that his most trusted confidant and one of his oldest friends had been killed.

Frederick continued advancing through Germany against the French/Imperial Army under Soubise and Hildburghausen who, not willing to engage the king, kept falling back before him. During these marches Frederick rode with Seydlitz and the advance guard of the army. On September 15 Frederick, escorted by cavalry elements of the advance guard, entered Gotha. Wrote one witness: “His complexion and the state of his clothing and shirt serve to confirm what is generally said of him, that in the field he makes himself no more comfortable than the least of his officers.” Frederick departed the following day, but on September 17 a strong reconnaissance force, estimated at between nine and ten thousand troops and led by Soubise and Hildburghausen, approached the city—the allied commanders had heard that the Prussians were in Gotha and had come to see for themselves.

Seydlitz prepared a ruse for them. Deploying his 1,500 cavalry in a long line outside the city, he sent several peasants and a man posing as a deserter into Gotha to spread the word that Frederick was approaching with the entire Prussian army. The allies beat a hasty retreat, leaving behind a number of their servants, ladies, baggage, and 80 soldiers whom Seydlitz took as prisoners. Recalled a participant: “Only a few soldiers were captured, but in compensation the Prussians took all the more valets, lackeys, cooks, friseurs, courtesans, field chaplains and actors—all the folk inseparable from a French army. The baggage of many commanders also fell to the Prussians—whole chests of perfumes and scented powders, and great quantities of dressing gowns, hair nets, sun shades, nightgowns and parrots.” The Prussian cavalry amused themselves by rifling through the French baggage, trying on the gowns of the ladies and playing with the parrots. Frederick subsequently called a halt to the pursuit and pulled back slightly to give his army a much needed rest.

Their respite was a short one because the Austrians, now deep in Silesian territory, had dispatched a small force of some 3,400 light troops under Lt. Gen. Andreas Hadik on a raid against Frederick’s capital at Berlin. Hadik reached the defenseless capital on October 16 and demanded a tribute of 215,000 thalers to spare the city from looting. He also asked for a dozen pairs of gloves stamped with the city’s municipal coat of arms because “he wished to make a present to his Empress,” Maria Theresa. Hadik left the city the following day, well before Prince Moritz and his 8,000-man relief force arrived. The raid was a minor one, but demonstrated that even Frederick’s capital, although of little importance as long as the king and his army survived, was not safe from the reach of the allies.

Leaving Field Marshal James Keith to cover the Saale River line, Frederick had marched with the bulk of the army to rescue Berlin. He then received information that the allies, having taken advantage of his absence, had crossed the Saale River and were marching on Leipzig. By advancing across the Saale they had presented Frederick with an opportunity to finally bring them to battle. Detaching Prince Moritz to deal with the raiding party, Frederick quickly reversed his march and moved toward Leipzig, ordering all elements of the army to join him there. On October 24 he reached Torgau where, despite the urgency of the situation, he halted for a day so that the army could receive their annual uniform issue. By the end of October he had concentrated the army at Leipzig, whereupon the allies, still refusing to give battle, fell back across the Saale.

Frederick was determined that they would not escape again, and accordingly decided to force a crossing of the river at two points. While Keith’s detachment made a crossing downstream at Merseburg, Frederick would make a crossing upstream at Weissenfels with the main army. On October 31 Frederick’s advance guard stormed the gates of Weissenfels, cutting off and capturing some 300 German soldiers guarding the town. The king positioned a battery of heavy guns on the bluff overlooking the Saale to stop a French counterattack and then rode to the riverbank where he watched as the French retired, thwarting his efforts to cross by burning the covered wooden bridge as they fell back.

Noting Frederick’s presence at the river, a French soldier named Brunet informed his commander, the Duke de Crillon, and suggested that a good marksman could probably hit the king at that range. Crillon later wrote: “Crillon handed his loyal Brunet a glass of wine, and sent him back to his post, remarking that he and his comrades had been put there to observe whether the bridge was burning properly, and not to kill a general who was making a reconnaissance, let alone the sacred person of a king, which must always be held in reverence.”

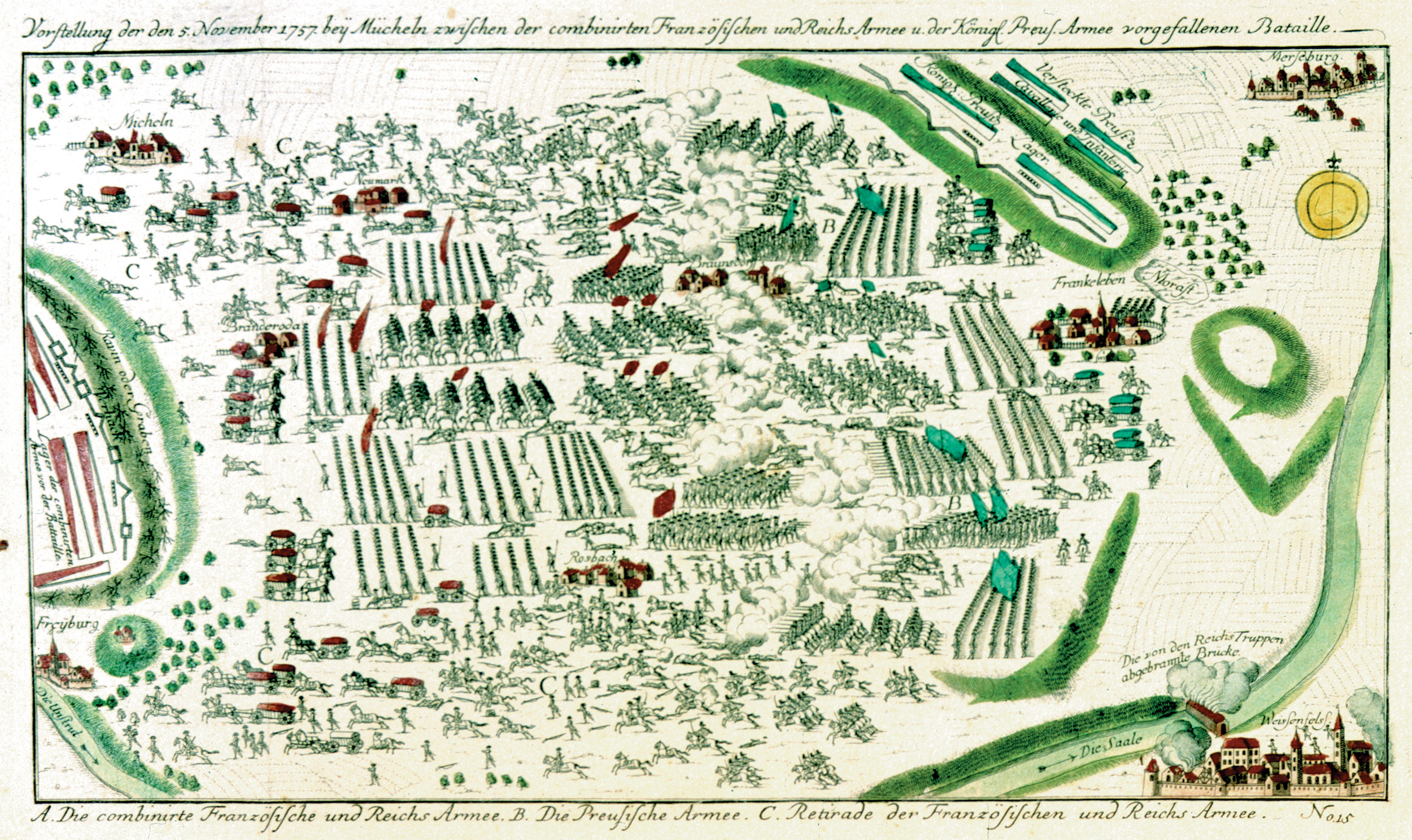

Undaunted, Frederick moved downstream, finally finding a satisfactory crossing point. Here, a fisherman named Mund built a bridge of boats for Frederick’s army to cross the river. (In 1813, this same fisherman in his old age would repeat this service for Field Marshal Blücher’s Prussian army.) On the morning of November 3 Frederick’s army crossed unopposed to the west bank of the Saale and advanced toward Braunsdorf. That evening Keith’s force, having effected its crossing at Merseburg, joined the main army. Frederick learned that the allies had their camp near Muchelin, facing north because they expected the Prussians to advance from the direction of Halle. In this position, the king thought to attack their right flank the following morning.

When the allies discovered Frederick had passed the Saale and was behind them, they quickly turned their camp east to face him. In the predawn darkness of November 4 Frederick personally reconnoitered the allied position. He saw that the enemy had moved their camp during the night and were now in a heavily fortified position that was much too strong for a direct assault. Furthermore, the allied army composed of 30,200 French and 10,900 Germans, totaled some 41,000 men in 62 battalions, 82 squadrons, and 114 guns (45 of them heavy guns). Outnumbered by nearly two to one, Frederick ordered his army to halt and take up positions behind the Leiha-Bach heights with his headquarters in the village of Rossbach.

To meet the allied force, Frederick had roughly 22,000 men in 27 battalions, 45 squadrons with 25 heavy guns. Knowing the allies were running low on provisions he decided to take up a position and await their next move. His position allowed the allies only two choices—either come out and fight or conduct a dangerous retreat before him toward the Unstrut River. The long weeks of sparring were over and the allies would soon oblige Frederick with the battle he desired.

The lack of an attack, combined with the Prussian army’s withdrawal to a more secure position near Braunsdorf, convinced the allies that Frederick had lost his nerve and was retreating. Frederick himself wrote that as a result, “All their complements of musicians, trumpeters, drummers, and fifers now gave sound, as if they had won some great victory.” This gave the allies new heart and they planned to take advantage of this apparent success by attacking the Prussian position. The exuberant cheers of the French soldiers grated on the Prussian troops, who nevertheless continued their march toward Braunsdorf. They would get their due from these Frenchmen soon enough.

The allied plan was relatively simple—a turning movement of Frederick’s left flank. To accomplish this, three large columns, screened by the corps of Saint-Germain positioned along the Schortau heights, were to march south for Zeuchfeld, as if attempting to escape the Prussians. They would then execute a wheel to the left that would bring them onto the Prussian left rear. Encountering numerous delays and confusion inherent with such unwieldy formations (which resulted in an unintentional fourth column being created), the allies finally got their columns in motion around 11:30 am on November 5. Reaching Zeuchfeld in the early afternoon they made their left wheel and began to march over a wide and open ridge that led past the Prussian left.

Early that morning Frederick had watched the flurry of activity in the allied camp from the roof of his headquarters at the Herrenhaus on the southern edge of Rossbach. It appeared that the allies were moving south toward Zeuchfeld and away from his army. Frederick began to take lunch with his staff.

Captain Friedrich Wilhelm Gaudi, an officer of the Guides, had watched from the rooftop as the allied columns turned at Zeuchfeld and headed east toward Pettstädt. He raced downstairs in a great state of excitement to inform the king. At first Frederick dismissed this report as merely alarmist, but later climbed to the roof and saw for himself that Gaudi was correct—the allies had turned and were marching for his left flank. For several minutes he watched the movement of the columns and then gave the order to quickly set his army in motion. By around 2:15 in the afternoon Frederick’s army was under way. Alles observed that “in less than two minutes all the tents lay on the ground, as if they had collapsed like theatrical scenery, and his army was in full march.”

In the few minutes he had observed the enemy movements and the surrounding terrain, Frederick had conceived his battle plan. The army would move to cut off the allied advance, utilizing the low ridge of Janus Hill to screen their march. They would first move northeast, giving the impression of retreating, then would make a wide swing to the south and finally turn west, bringing them in front of the allied columns, thus cutting off their advance and attacking them while they were still on the march. Leaving Prince Ferdinand with the right wing of the army to make a demonstration in front of their original position, Frederick ordered two lines of the army to quarter-wheel to the left, thus forming them into two marching columns.

Major General Seydlitz Authoritatively Took Charge of the Cavalry

To Maj. Gen. Seydlitz he gave the remaining cavalry of the army, 38 squadrons, to serve as the vanguard. Seydlitz, using the numerous hollows in the area to screen his movements, was ordered to drive off the French cavalry leading the allied columns, and attack their infantry before it could form. Because the cavalry had the farthest to go, Frederick ordered them to move immediately. Seydlitz, a major general for only a few months, jumped in the saddle and rode straight to the cavalry generals, and with the voice of authority informed them, “Gentlemen, I obey the king, and you will obey me!” The cavalry duly set out with the infantry columns racing along behind, trying to keep pace.

Still believing that Frederick was retreating, the allies tried to hurry their movement, unaware that the Prussians were in fact moving parallel to them and fast approaching a juncture. The cumbersome formation and the closeness of the allied columns made the march difficult and slowed them considerably. The terrain was too rugged and uneven for such large formations to maneuver with any order, forcing them to break off and re-form as they moved. Jay Luvaas, the translator of Frederick the Great on the Art of War, wrote: “The left column, or first line, consisted of sixteen German squadrons, sixteen French battalions, and twelve French squadrons: this was the only column that marched on the road. The others followed parallel routes across the fields, the second line, or column, comprising seventeen German squadrons and sixteen French battalions, and the third column, the French reserve corps and fourteen battalions of German infantry, followed by the German artillery reserve.”

Reaching a position behind Janus Hill, the Prussian columns wheeled to the right and advanced up the slope. As the infantry neared the crest, Frederick placed Colonel Karl von Moller’s 18 heavy guns in battery on the summit. At approximately 3:15 pm, the barking of Moller’s guns announced the opening of the Prussian attack. Several miles away the civilians in the area stated that the ground “trembled under our feet, and the noise exceeded the worst roll of thunder.”

Seydlitz, having formed his squadrons into line, continued moving forward in this formation until he reached a suitable attack position slightly beyond the eastward extension of Janus Hill. In his first line, from left to right, were the Leib Cuirassiers (Bodyguard), and the Meinicke and Czettritz Dragoons, totaling 15 squadrons. His second line of 18 squadrons consisted of the Driesen and Rochow Cuirassiers, the Gens d’Armes, and the Garde du Corps. Covering the left flank were five squadrons of the Szekely Hussars.

Facing Seydlitz were the 33 squadrons of the allied advance guard. In front were the Austrian cuirassier regiments Bretlach and Trautmannsdorf. Behind them in support were three regiments of Imperial German Horse and the Austrian Szekely Hussars. Positioning his squadrons in a suitable attack position behind a low ridge, Seydlitz watched and waited as the allied cavalry approached the slopes of Janus Hill. When the enemy was a thousand paces distant, Seydlitz saw his moment. Ordering the trumpets to sound “Marsch! Marsch!,” he threw his tobacco pipe over his shoulder as a signal to charge, and the 15 squadrons of the first line descended upon the enemy. Taken by surprise, only the Bretlach and Trautmannsdorf Regiments had time to form into battle line before the Prussians struck. The commander of the Bretlach Cuirassiers, the Duke of Voghera, raised his sword in salute to the Prussian general opposing him. The salute being returned, Voghera then threw his regiment into the charge. The two forces clashed and locked in a mass of slashing troopers and plunging horses. Although caught unprepared, the weight of allied numbers managed to withstand the Prussian assault.

Seeing their comrades heavily engaged, 24 squadrons of French cavalry rode forward to enter the fray. Seydlitz then committed his second line to the attack. The timing was perfect. Eighteen Prussian squadrons, supported by the five squadrons of Szekely Hussars, caught not only the allied advance guard, but also the reinforcing French squadrons in a double-flank attack. Wrote Christopher Duffy in his Army of Frederick the Great: “The low German cry of ‘Gah to!’ burst from the Brandenburgers and Pomeranians of the cuirassiers, giving one of the French officers occasion to wonder what kind of men were these who went into battle crying ‘Cake!’”

Now it was the Prussians that had both the weight and the impetus, and they began forcing back the disorganized mass of allied cavalry. The swirling melee finally reached the sunken road that connected Reichardtswerben and Tagewerben. Pressed on three sides and with a seemingly impassable obstacle in their rear, the 57 squadrons of allied cavalry broke and fled, racing back toward their infantry support.

Instead of continuing the pursuit of the fleeing enemy, Seydlitz called a halt and rallied his squadrons. Demonstrating superior judgment and great tactical discipline, he knew the battle was far from over and that his cavalry would be needed again before the day was done. He moved his troopers southeast of Reichardtswerben to a hollow between Tagewerben and Storkau on the allied right flank. Here he re-formed their lines and awaited his next opportunity.

As the allied advance guard was retreating back on their main body, the Prussian infantry had crossed the ridge of Janus Hill and in echelon of battalions by the left were quickly moving south. Frederick’s objective was Reichardtswerben but the village was 600 paces away, and the gap between his infantry and the allied columns was closing fast. Expecting to engage at any minute, and not having enough time to reach Reichardtswerben, Frederick ordered Marshal Keith with all five battalions of the second line to race ahead to the village while he wheeled the rest of the army right into line. Keith reached Reichardtswerben and formed his battalions in line in front of the village. The Prussian army was now arrayed in a kind of dog-leg pattern, facing southwest. Moller’s battery, having been moved off the heights, was now situated slightly behind the angle of the line. The allied columns, advancing across the plain at the base of the ridge, were rapidly approaching the dog-leg angle. Frederick ordered two combined grenadier battalions on the far left of the line to half-wheel to the right once the allied columns entered the angle, thus forming a hook that could fire into the allied right flank.

With the Prussians now formed in line to their front, the lead regiments of the allied columns tried to deploy into some kind of battle order. To the front and left were the French regiments Piemont, St. Chamont, Mailly, La Marck, Poitou, and Provence. With little time and limited space they could not form a firing line, but instead deployed into the best formation they could, a self-containing attack column. To their right were the Imperial regiments Blau-Würzburg, Hessen-Darmstadt, and Kur-Trier.

The Prussian troops withheld their fire until the enemy was within 40 paces. The lead allied battalions were then met by the devastating fire of platoon volleys from the Alt-Braunschweig and Kleist infantry regiments and the heavy guns of Moller’s battery. This massive discharge shredded their front ranks and threw their columns into confusion. The combined fire of seven Prussian infantry battalions and their heavy guns then swept the allied formation from the front and right flank. At about this time Frederick, who was with the Alt-Braunschweig Regiment, wandered in front of their line, causing the soldiers to cry out, “Father, please get out of the way, we want to shoot!”

Unable to advance against the heavy Prussian fire, the allied lead battalions halted with the following columns pressing into them. Attempting to deploy to the left to escape the flanking fire only added to their growing confusion. The farther to the left the mass of infantry moved, the more they were outflanked on their right. The French had positioned a battery of eight guns at the bottom of the ridge and these attempted to respond, but they were firing upward and had no effect.

Seydlitz, watching from the hollow between Tagewerben and Storkau, saw his moment and threw his squadrons in a massed charge against the allied right. Smashing into the French cavalry screen, Seydlitz’s squadrons sliced through them and charged on into the mass of allied infantry beyond. The charge of the Prussian cavalry was too much and the allied columns simply dissolved into a frightened, fleeing mass before Seydlitz’s troopers. A French soldier recalled that “everybody sank into a mob, and it was impossible to restore or stay the flight, whatever the efforts of the entire corps of generals and officers. The Prussian infantry followed on the heels of ours, and fired without checking its advance or having a man drop out of rank or file. The artillery shot us up without respite.”

The Prussians now “got back their own,” their cavalry hacking and hewing at the French infantry without mercy. Captain Gaudi commented on “the natural hate which the common men in Germany, but especially the Magdeburgers, Brandenburgers and Pomeranians feel in their heart towards everything which bears the name of ‘French.’ It is something they absorb with their mothers’ milk. They are unaware of the reason, and when you press them for an answer they will say ‘it’s because a Frenchman cannot be a German’ … they fought with real hatred, as was most clearly shown in the behaviour of the cavalry when they hacked into the enemy infantry, for our officers had to go to great efforts to get the ordinary troopers to give quarter.”

The allied army lost more men during the pursuit of the Prussian cavalry than they had during the course of the battle. Wrote a participant: “The roads were strewn with French cuirasses and hats, and great riding boots which their owners had thrown aside in order to escape more easily in their shoes and stockings. The sunken road at Markwerben was full of Frenchmen who had been hacked down.”

10,152 Allied Men Killed, Wounded, or Captured

Not even the enemy commanders were spared. Prince Hildburghausen found himself surrounded by Prussian cavalry that repeatedly beat at him with the flat of their swords as he tried to escape. In trying to explain the outcome, Hildburghausen later told the Emperor that “everything sank into confusion. It was quite impossible to rally a single unit, and even when you thought you had got a squadron or a battalion together it needed only a cannon shot to come whizzing down and they all ran like sheep.”

The allies fled toward Pettstädt where the reserve units of Saint-Germain and Loudon, having moved south to cover the rout, managed to hold off the Prussians long enough for the mob to get to relative safety. By 5 pm it was all over and the battlefield was covered by the blessed shroud of night. The allied losses were 10,152 men killed, wounded, or captured. The Reichsarmee had lost 3,552 men, 21 standards, and 72 guns. The French lost a total of 6,600 men, of which 11 were generals. For this magnificent and total victory the Prussians paid with only 30 officers and 518 men.

Frederick was extremely pleased with Seydlitz’s performance and promoted him to lieutenant general, awarded him the Order of the Black Eagle, and gave him the Rochow Cuirassier Regiment, which bore his name from that day forth. The king was also pleased with those units that had shown great courage during the fight. The Leib Cuirassiers were praised by the king, while the Alt-Braunschweig Regiment, one of only seven infantry units engaged, was awarded 15 Pour le Meritesr and the king’s thanks for their particular bravery and conduct.

That evening Frederick wrote his sister Wilhelmine, saying, “I can now die in peace, because the reputation and honor of my nation have been saved. We may still be overtaken by misfortune, but we will never be disgraced.” Outnumbered, his nation pressed on all sides, Frederick’s army had outmaneuvered and outfought the allies, shattering one of their major armies in less than 21/2 hours. As a result of the victory at Rossbach, Great Britain disavowed the treaty of Kloster-Zeven, refitting its army and allowing overall command to fall to the highly talented Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick. For the next few years, Brunswick guaranteed the security of Frederick’s strategic western flank, keeping the main French effort occupied on their side of the Rhine.

Captain Gaudi’s considered opinion of the battle was that “if the king was able to turn the tables so masterfully in his favor, if he managed to counter the deadly designs of the enemy with such skill and speed, he owed it entirely to his own considerable talents. On the day of this battle he showed himself in his true greatness, as will be testified by all informed observers who were present at the event.” Frederick’s comment on the battle was “strictly speaking, the Battle of Rossbach merely afforded me the freedom to go in search of new dangers in Silesia.” That search would lead him within a month to another victory, the greatest victory of his career, on the field of Leuthen.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments